Abstract

Osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG) is a rare genetic disease that produces debilitating effects in the skeleton. OPPG is caused by mutations in LRP5, a WNT co-receptor that mediates osteoblast activity. WNT signaling through LRP5, and also through the closely related receptor LRP6, is inhibited by the protein sclerostin (SOST). It is unclear whether OPPG patients might benefit from the anabolic action of sclerostin neutralization therapy (an approach currently being pursued in clinical trials for postmenopausal osteoporosis) in light of their LRP5 deficiency and consequent osteoblast impairment. To assess whether loss of sclerostin is anabolic in OPPG, we measured bone properties in a mouse model of OPPG (Lrp5−/−), a mouse model of sclerosteosis (Sost−/−), and in mice with both genes knocked out (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−). Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice have larger, denser, and stronger bones than do Lrp5−/− mice, indicating that SOST deficiency can improve bone properties via pathways that do not require LRP5. Next, we determined whether the anabolic effects of sclerostin depletion in Lrp5−/− mice are retained in adult mice by treating 17-week-old Lrp5−/− mice with a sclerostin antibody for 3 weeks. Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice each exhibited osteoanabolic responses to antibody therapy, as indicated by increased bone mineral density, content, and formation rates. Collectively, our data show that inhibiting sclerostin can improve bone mass whether LRP5 is present or not. In the absence of LRP5, the anabolic effects of SOST depletion can occur via other receptors (such as LRP4/6). Regardless of the mechanism, our results suggest that humans with OPPG might benefit from sclerostin neutralization therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal diseases that result in low bone mass are a major public health concern in the United States (1, 2). In particular, postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO)—a condition driven by estrogen depletion that leads to excessive bone resorption and increased fracture risk—is alarmingly prevalent in women more than 50 years of age (3). Many antiresorptive therapies aimed at inhibiting bone loss are approved, or are in late-stage trials, including bisphosphonates (such as alendronate), selective estrogen receptor modulators (such as raloxifene), and anti-bodies that recognize osteoclastogenic factors (such as denosumab) and/or enzymes crucial to the resorption process (such as odanacatib), among others. Although these compounds are effective in stemming further loss of bone, and consequently improve bone mineral density (BMD), other low bone mass diseases that are primarily fueled by reduced bone formation, rather than increased resorption (as is the case with PMO), might reap less benefit from antiresorptive therapy.

Osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG) is one such disease, where bone resorptive activity is normal, but bone formation is markedly reduced (4). The severe deficit in osteoblastic activity among OPPG patients has profound consequences on the skeleton, and their BMDs are typically about 5 SDs below normal. This degree of osteopenia is far beyond the skeletal deficits seen in PMO, and the number and degree of fractures sustained by patients with OPPG attest to the severity of the disease (5). The underlying osteoblastic deficits suggest that anti-resorptive therapies might not be as effective as anabolic therapies in restoring the skeleton to its proper mass and strength.

Currently, only one U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved compound has anabolic action in the skeleton—an N-terminal fragment of the human parathyroid hormone (PTH) (teriparatide). Teriparatide treatment appears efficacious in some OPPG patients (6), but not others (7). Although data beyond case reports would bring more clarity to this issue, the inconsistency in teriparatide efficacy in OPPG patients highlights the need for more anabolic treatment options, particularly those that are reliable and efficacious in OPPG patients.

In 2001, we reported that the genetic basis for OPPG is a loss-of-function mutation in low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 5 (LRP5), which functions as a co-receptor for the large family of WNT ligands (4). Lrp5-null mice recapitulate the OPPG phenotype seen in humans, and the low bone mass phenotype in these animals appears to be driven by severely compromised bone formation, with no detectable changes in bone resorption (8, 9). LRP6 is a closely related receptor to LRP5, and like LRP5, it participates in WNT signaling and plays a role in the regulation of bone mass. Loss-of-function mutations in LRP6 in humans and mice yield low bone mass phenotypes (10–12). However, much less is known about how LRP6 functions in bone, whether it affects predominantly resorption or formation, how it might differ from LRP5 in its ligand specificity and downstream signaling, and whether and to what extent it can substitute for LRP5 when LRP5 is mutated or deleted.

One promising bone anabolic therapy that is currently under development (currently in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials) is a monoclonal antibody to sclerostin, the protein product of the SOST gene. Sclerostin binds and inhibits LRP5 and LRP6, thereby reducing WNT signaling through these receptors (13–18). Sclerostin inhibition has been shown to increase bone mass and strength indices in mice, rats, and monkeys and to increase BMD in humans (19–27). We sought to determine whether OPPG patients might benefit from the anabolic action of anti-sclerostin therapy, despite having no LRP5. Our goal was to learn whether signaling through LRP6, or a sclerostin target other than LRP5, could induce anabolic action in the absence of LRP5. We report that in mouse models, not only does SOST/sclerostin depletion remain osteoanabolic when LRP5 is deleted, but remarkably, the magnitude of the effect is very large. This result suggests that anabolic action in bone can occur through LRP6 or through other yet undiscovered mechanisms that do not involve LRP5. Regardless of the mechanism, our data suggest that the severely reduced bone mass and greatly elevated fracture incidence found among patients with OPPG syndrome might be treatable using therapies that inhibit sclerostin activity.

RESULTS

Mice lacking LRP5 and SOST have higher bone mass than those lacking LRP5 alone

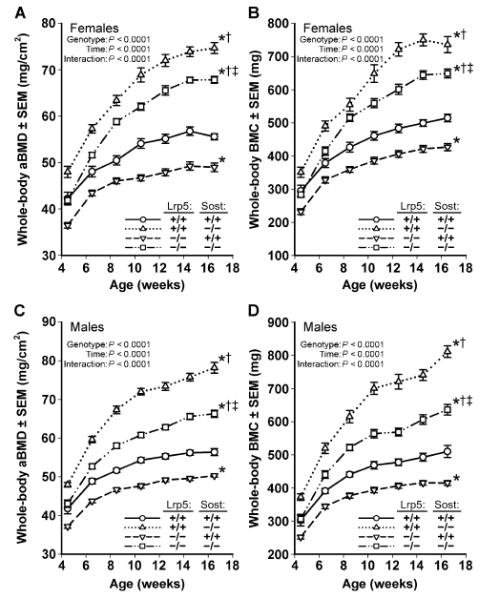

Mice that lack SOST (Sost−/−) exhibit abnormally high bone mass (HBM), whereas mice that lack LRP5 (Lrp5−/−) exhibit abnormally low bone mass. To assess whether a lack of LRP5 would alter the HBM phenotype in Sost−/− mice, we generated mice lacking both LRP5 and SOST (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−) and evaluated the resulting phenotypes. Sost−/− and Lrp5−/− mice served as positive and negative controls, respectively, and wild-type mice served as a bone-normal reference population. As expected, whole-body BMD and bone mineral content (BMC) were increased in Sost−/− mice and decreased in Lrp5−/− mice (Fig. 1). Mice that lacked LRP5 and SOST (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−) had whole-body BMD and BMC values that were greater than those measured for Lrp5−/− mice and were inter mediate between those of wild-type and Sost−/− mice (Fig. 1). Body weight did not differ between the four genotypes in either cohort after adjusting for sex (fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Longitudinal whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)–derived measures of areal BMD (aBMD) (A and C) and BMC (B and D), collected in female (A and B) and male (C and D) mice.

Scans were collected biweekly beginning at 4.5 weeks of age until 16.5 weeks of age in wild-type mice (circles; solid line), Sost−/− mice (triangles; dotted line), Lrp5−/− mice (inverted triangles; dashed line), and Sost−/− Lrp5−/− double knockouts (squares; interrupted dashed line). *P < 0.05, significant difference from wild-type mice; †P < 0.05, significant difference from Lrp5−/− mice; ‡P < 0.05, significant difference from Sost−/− mice, using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). For each group, n = 9 to 14 mice.

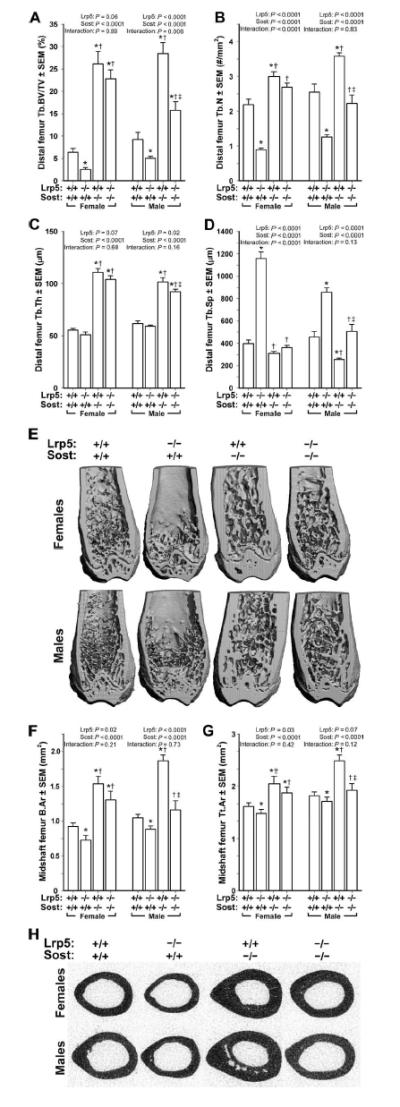

Comparable findings were observed when micro–computed tomography (mCT) measures of bone mass were obtained (Fig. 2, A to E). Bone volume fraction (BV/TV) increased in Sost−/− mice and decreased in Lrp5−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 2A). Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice exhibited greater BV/TV values than did Lrp5−/− mice and were intermediate between those of wild-type and Sost−/− mice. Female Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice exhibited a greater increase in BV/TV and trabecular number (Tb.N) than did male mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Genotype-related differences in cortical bone properties (Fig. 2, F to H) were similar to those observed for trabecular bone.

Fig. 2. mCT-derived measurements of the distal femur trabecular bone and midshaft femur cortical bone in wild-type, Lrp5−/−, Sost−/−, and Lrp5−/− Sost−/− mice, collected from male and female mice at 16.5 weeks of age.

(A) Trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV). (B) Trabecular number (Tb.N). (C) Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th). (D) Trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). (E) Representative cut-away (anterior portion digitally removed to reveal the metaphysis) μCT images of distal femur from the genotypes indicated in (A) to (D). Note the reduced trabecular bone mass induced by the Lrp5 mutation, the marked increase in trabecular bone induced by the Sost mutation, and the elevated trabecular bone mass in the double knockouts. (F and G) Midshaft femur bone tissue area (B.Ar) (F) and midshaft femur total area (Tt.Ar) (G) within the periosteal boundary. (H) Representative midshaft femur μCT images from the genotypes indicated in (F) and (G). Note the reduced cortical bone mass induced by the Lrp5 mutation, the marked increase in cortical bone induced by the Sost mutation, and the elevated cortical bone mass in the double knockouts. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA within sex using Lrp5 and Sost genotypes as main effects (indicated at the top of each panel). Post hoc tests were conducted using Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD). *P < 0.05, significantly different from wild type; † P < 0.05, significantly different from Lrp5−/−; ‡ P < 0.05, significantly different from Sost−/−. For each group, n =9 to 14 mice.

Mice lacking LRP5 and SOST have enhanced bone mechanical properties and greater periosteal bone formation rates than those lacking LRP5 alone

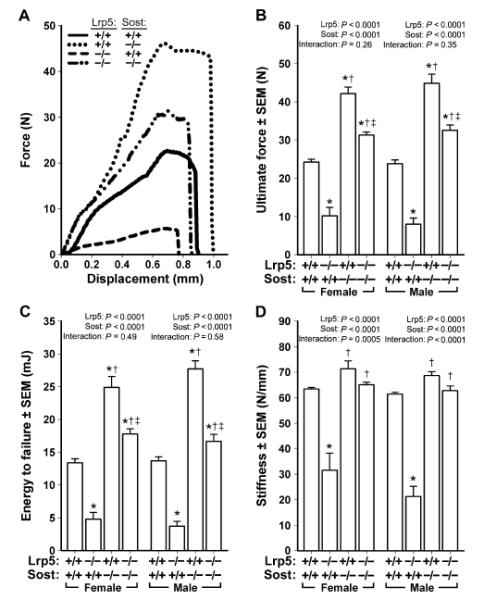

Having found that Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice exhibited elevated bone mass and architectural properties beyond wild-type and Lrp5−/− controls, we sought to learn if those effects translated into enhanced bone strength. Ultimate force, energy to failure, and stiffness were all increased in Sost−/− mice and decreased in Lrp5−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3). Femurs from mice that lack LRP5 and SOST (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−) were stronger than those from Lrp5−/− mice and were even stronger than those from wild-type mice.

Fig. 3. Monotonic three-point bending tests to failure of femora from 16.5-week-old male and female wild-type, Lrp5−/−, Sost−/−, and Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice.

(A) Representative force-displacement curves (male mice depicted) derived from the four genotypes tested. (B to D) Note the mutation-associated changes in peak curve height [ultimate force; quantified in (B)], area under the curve [energy to failure; quantified in (C)], and slope of the elastic portion of the curve [stiffness; quantified in (D)]. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA within sex using Lrp5 and Sost genotypes as main effects (indicated at the top of each panel). Post hoc tests were conducted using Fisher’s PLSD. *P < 0.05, significantly different from wild type; † P < 0.05, significantly different from Lrp5−/−; ‡ P < 0.05, significantly different from Sost−/−. For each group, n = 9 to 14 mice.

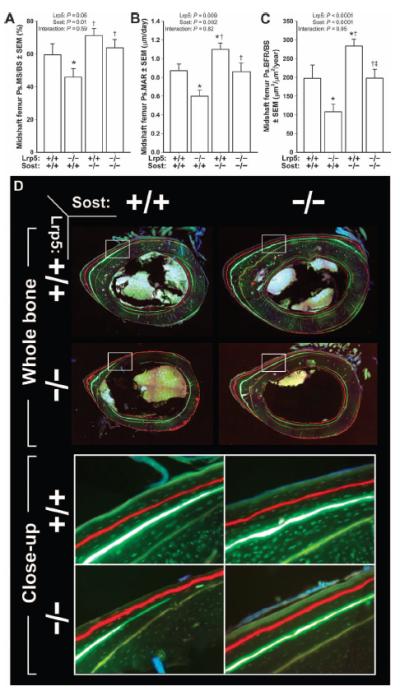

To determine whether the increased strength in the femurs of Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice compared to Lrp5−/− mice was due to increased anabolism, we measured bone formation parameters on the periosteal surface of the midshaft femur of male mice (Fig. 4). We injected fluorochrome labels at 5, 8, and 12 weeks of age, but we used the 5- and 12-week labels for histomorphometry to capture the genotype effects over the largest time span (Fig. 4D). Mineralizing surface per unit bone surface (MS/BS) was reduced in Lrp5−/− mice compared to wild-type mice but not in either Sost−/− or Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice (Fig. 4A). Mineral apposition rates (MARs) and bone formation rates (BFRs) were increased in Sost−/− mice and decreased in Lrp5−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4, B and C). MAR and BFR in Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice were increased compared to Lrp5−/− mice and did not differ from wild-type mice. Osteoblast surface in the distal femur metaphysis exhibited similar trends to the midshaft BFR results, whereas osteoclast surface was not affected by genotype (fig. S2).

Fig. 4. Midshaft femur fluorochrome-derived BFRs on the periosteal surface collected from 16.5-week-old male Lrp5−/−, Sost−/−, and Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice.

(A) Periosteal MS/BS (Ps.MS/BS). (B) Periosteal MAR (Ps.MAR). (C) Periosteal BFR per unit bone surface (Ps.BFR/BS). All three indices were derived using an oxytetracycline label given at 5 weeks of age [pale yellow label in (D)] and an alizarin complexone label given at 12 weeks of age [red label in (D)]. (D) Whole-bone (upper panels) and close-up (lower panels; taken from the white boxes indicated in the upper panels) photomicrographs of representative midshaft femur sections from each of the four genotypes studied. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Lrp5 and Sost genotypes as main effects [indicated at the top of panels (A) to (C)]. Post hoc tests were conducted using Fisher’s PLSD. *P < 0.05, significantly different from wild type; † P < 0.05, significantly different from Lrp5−/−; ‡P < 0.05, significantly different from Sost−/−. For each group, n = 8 mice.

Sclerostin antibody therapy improves bone properties and bone formation in adult mice lacking LRP5

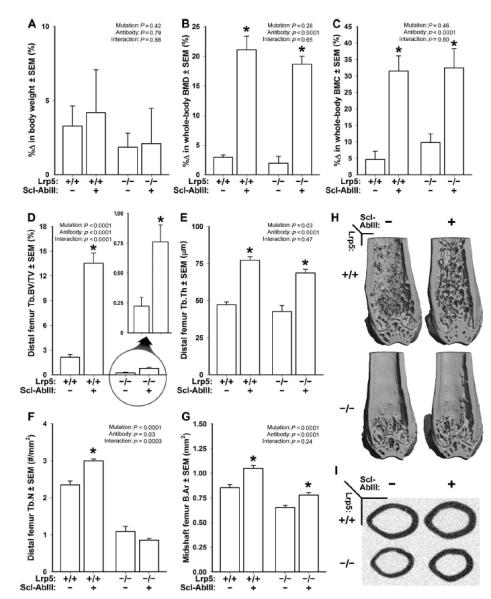

Our data indicate that the absence of SOST beginning in fetal life increases bone properties in wild-type and Lrp5−/− mice. We tested the ability of sclerostin inhibition to improve bone properties in adult mice by treating naïve Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice with a 3-week course of sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII) or vehicle alone beginning at 17 weeks of age (Fig. 5). Neither Lrp5 genotype nor Scl-AbIII therapy affected body weight over the experimental period (Fig. 5A). Whole-body BMD and BMC were increased in both Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice compared to their genotype-matched vehicle-treated controls, but no genotype-related differences in responsiveness to Scl-AbIII were detected (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5. DEXA- and mCT-derived measurements of bone mass, density, and architecture in female Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice that had been treated for 3 weeks with vehicle or sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII).

(A) Percent change in body weight over the 3-week experimental period. (B) Percent change in whole-body aBMD over the 3-week experimental period. (C) Percent change in whole-body BMC over the 3-week experimental period. (D) Distal femur trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV) after 3 weeks of treatment with vehicle or antibody. An enlarged view of the antibody effect in Lrp5−/− mice is provided (circle with arrow) because baseline BV/TV is so low in these mice. (E) Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) after 3 weeks of treatment with vehicle or antibody. (F) Trabecular number (Tb.N) after 3 weeks of treatment with vehicle or antibody. (G) Midshaft femur cortical bone area (B.Ar) after 3 weeks of treatment with vehicle or antibody. (H) Representative cut-away (anterior portion digitally removed to reveal the metaphysis) mCT images of distal femur from the treatment groups indicated in (A) to (G). (I) Representative midshaft femur mCT slice from the treatment groups indicated in (A) to (G). The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Lrp5 genotype and antibody/vehicle treatment as main effects (indicated at the top of each data panel). Post hoc tests comparing antibody treatment to vehicle treatment within Lrp5 genotypes were conducted using Fisher’s PLSD. *P < 0.05, significant difference from vehicle-treated mice. For each group, n = 8 mice.

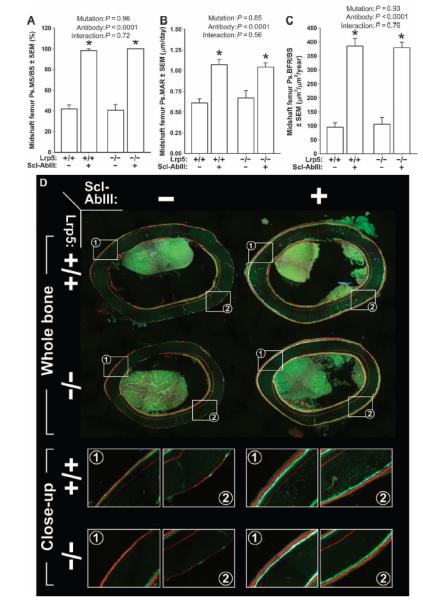

μCT measurements of trabecular and cortical bone in wild-type and Lrp5−/− mice indicated that Scl-AbIII therapy increased bone mass in both compartments (Fig. 5, D to I). For BV/TV, an Lrp5 genotype by Scl-AbIII interaction was detected (Fig. 5D), suggesting that Lrp5 status affected the response to therapy. However, the very low starting BV/TV values in Lrp5−/− mice likely had an overriding effect on the interaction term (Fig. 5D). In support of this interpretation, when trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) was measured, Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice had similar responses to therapy (Fig. 5E). Midshaft cortical bone area exhibited comparable increases in Scl-AbIII–treated Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice. Fluorochrome labeling of bone after 1 and 2 weeks of treatment revealed that MS/BS, MAR, and BFR were increased in mice receiving Scl-AbIII compared to those receiving vehicle alone, regardless of Lrp5 genotype (Fig. 6). Osteoblast surface in the distal femur metaphysis was elevated by Scl-AbIII treatment in both Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice, whereas osteoclast surface was reduced modestly by antibody treatment only in wild-type mice (fig. S3).

Fig. 6. Midshaft femur fluorochrome-derived BFRs on the periosteal surface of 20-week-old female Lrp5+/+ and Lrp5−/− mice that had been treated for 3 weeks with vehicle or a sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII).

(A) Periosteal MS/BS (Ps.MS/BS). (B) Periosteal MAR (Ps.MAR). (C) Periosteal BFR per unit bone surface (Ps.BFR/BS). All three indices were derived using a calcein label given at 18 weeks of age [green label in (D)] and an alizarin complexone label given at 19 weeks of age [red label in (D)]. (D) Whole-bone (upper panels) and close-up (lower panels; taken from the white boxes indicated in the upper panels) photomicrographs of representative midshaft femur sections from each of the groups studied. A xylenol orange label can be seen in some of the sections buried deeper in the cortex (given at 12 weeks of age), which served as a pretreatment marker and was not used for any of the dynamic measurements. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Lrp5 genotype and antibody/vehicle treatment as main effects (indicated at the top of each panel). Post hoc tests comparing antibody treatment to vehicle treatment within Lrp5 genotypes were conducted using Fisher’s PLSD. *P < 0.05, significant difference from vehicle-treated mice. For each group, n = 8 mice.

Sclerostin inhibition affects multiple pathways

In light of our observation that sclerostin antibody was anabolic in Lrp5−/− mice, we sought to learn whether anabolic signaling pathways other than Wnt are altered in bone when sclerostin is inhibited. We looked for evidence of enhanced bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling [BMPs have been proposed to be sclerostin binding partners (28, 29)] in tissue sections from Sost−/− and Scl-AbIII–treated mice, using immunodetection of phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8 (p-Smad 1/5/8). No differences in the number of p-Smad 1/5/8–positive osteocytes were detected in cortical bone among Sost−/− or Scl-AbIII–treated mice, although a large amount of variation in staining was detected, making the potential effect on BMP signaling equivocal (fig. S4). Next, we took a broader approach by treating 10-week-old wild-type male mice with Scl-AbIII or vehicle for 2 weeks and generated individual bar-coded RNA sequencing libraries from each mouse’s tibial cortical bone for use in massively parallel sequencing (RNA-seq). Eighty-five genes were found to be expressed at significantly different quantity in mice that received Scl-AbIII versus those receiving vehicle (table S1). We previously reported tibia bone RNA-seq data from mice with and without functioning Lrp5 alleles and found significant expression differences in 84 genes (24). Because Scl-AbIII improved the skeletal phenotype in Lrp5−/− mice, we compared the genes affected by Scl-AbIII administration to those affected by Lrp5 deficiency. Twelve genes are within the intersection of the 85 genes affected by Scl-AbIII administration and the 84 genes affected by Lrp5 inactivation (Table 1). As would be expected, genes exhibiting lower expression in Lrp5−/− were more highly expressed in Scl-AbIII–treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice. No transcripts encoding components of key signaling pathways other than Wnt [such as BMP and FGF (fibroblast growth factor)] are contained within the intersection. However, the intersection does contain the two genes encoding type I collagen, which is the major structural matrix protein in bone.

Table 1.

Genes whose expression is significantly lower in Lrp5−/− bone compared to wild-type bone, and higher inwild-type bone treated with Scl-AbIII compared to vehicle alone. Differences in expression between mice lacking Lrp5 (Lrp5−/−) and mice with functioning Lrp5 (Lrp5+/+ or Lrp5A214V/+) are reported as fold changes, along with their corresponding P values, as are the differences in expression between mice that received Scl-AbIII and those that received vehicle [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] alone.

| Gene | Protein product | Lrp5+/+

|

Lrp5−/−/Lrp5+/+

|

Lrp5−/−/Lrp5A214V/+

|

Scl-Ablll/PBS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPKM* | Fold change | P | Fold change | P | Fold change | P | ||

| Cpz | Carboxypeptidase Z | 11.55 | 0.16 | 1.08 × 10−24 | 0.18 | 7.29 × 10−17 | 4.77 | 2.72 × 10−13 |

| Slc13a5 | Solute carrier family 13 (sodium-dependent citrate transporter), member 5 |

64.14 | 0.17 | 9.76 × 10−24 | 0.18 | 1.81 × 10−17 | 4.77 | 7.90 × 10−14 |

| Col1a1 | Collagen, type 1, α1 | 1245.3 | 0.23 | 1.48 × 10−17 | 0.23 | 1.43 × 10−13 | 5.4 | 8.67 × 10−16 |

| Prss35 | Protease, serine, 35 | 34.62 | 0.24 | 1.16 × 10−15 | 0.41 | 4.05 × 10−5 | 4.57 | 3.22 × 10−13 |

| Col11a2 | Collagen, type XI, α2 | 94.39 | 0.25 | 2.14 × 10−15 | 0.29 | 8.05 × 10−10 | 4.08 | 1.75 × 10−11 |

| Bglap2 | Bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein 2 | 338.97 | 0.31 | 3.94 × 10−11 | 0.39 | 4.64 × 10−6 | 6.67 | 8.91 × 10−21 |

| Col1a2 | Collagen, type 1, α2 | 981.29 | 0.35 | 3.18 × 10−9 | 0.35 | 8.03 × 10−7 | 4.42 | 2.47 × 10−12 |

| Bglap | Bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein | 261.73 | 0.38 | 8.22 × 10−8 | 0.37 | 4.32 × 10−6 | 6.23 | 1.90 × 10−19 |

| Cdo1 | Cysteine dioxygenase 1, cytosolic | 63.39 | 0.42 | 4.87 × 10−6 | 0.32 | 2.65 × 10−7 | 3.42 | 3.92 × 10−9 |

| Cgref1 | Cell growth regulator with EF hand domain 1 | 25.61 | 0.48 | 2.05 × 10−4 | 0.43 | 1.81 × 10−4 | 4.01 | 7.19 × 10−11 |

| Kcnk1 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 1 | 10.08 | 0.48 | 3.37 × 10− 4 | 0.42 | 3.28 × 10−4 | 5.06 | 3.63 × 10−14 |

| Pla2g5 | Phospholipase A2, group V | 7.67 | 0.49 | 6.80 × 10−4 | 0.38 | 5.03 × 10−5 | 2.85 | 1.81 × 10−6 |

RPKM value is the reads per kilobase coding sequence per million reads for the transcript in wild-type bone. Higher RPKM values indicate higher levels of mRNA expression.

DISCUSSION

Our aim in the present communication was to determine whether the bone-building action of sclerostin inhibition requires functional LRP5 receptors. The low osteo-blastic activity measured in mouse models of OPPG (Lrp5−/−) and the enhanced osteoblastic activity measured in mouse models of LRP5 HBM disease (Lrp5g171v or Lrp5v214V) provided the rationale to suggest that sclerostin’s target for inhibition of bone formation is LRP5 (8, 9, 30, 31). We found that SOST deletion resulted in significantly increased bone mass, architecture, and strength, even when LRP5 was absent. The degree of enhanced skeletal properties among the double-knockout (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−) mouse mutants was not as great as was observed in the Sost−/− mice, but the skeletal properties in Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mice were significantly improved compared to Lrp5−/− mice and frequently exceeded those of wild-type mice. Moreover, sclerostin inhibition beginning in adulthood, achieved through twice-weekly administration of sclerostin antibody to 17-week-old female mice, improved bone properties in Lrp5−/− mice to the same extent as was found in Lrp5+/+ mice. Together, the data indicate that the anabolic effects of deleting SOST or inhibiting sclerostin can occur in the absence of LRP5, implying that sclerostin interacts with other proteins, in addition to LRP5, when exerting its negative effect on bone formation.

OPPG is a very rare genetic condition characterized, in part, by severe juvenileonset osteoporosis and a very high incidence of fractures. These patients exhibit BMDs that can reach ~5 SDs below age-matched normal individuals (25). Heterozygous carriers of OPPG-causing LRP5 mutations also have reduced bone mass (4, 32). There are limited data on the efficacy of different pharmacologic skeletal therapies in these patients because of the rarity of the disease. Some OPPG patients respond favorably to bisphosphonate therapy (7, 33, 34), whereas others do not (6). Likewise, teriparatide treatment appears efficacious in some OPPG patients (6), but not others (7). Our discovery of robust anabolic effects of sclerostin antibody in Lrp5−/− mice suggests that OPPG patients might reap significant bone-building benefits and decreased fracture incidence from anti-sclerostin therapy.

LRP6, which is closely related to LRP5 in sequence and structure (13, 35), plays a role in bone biology (10, 19), can substitute functionally for LRP5 in in vitro Wnt signaling assays (17, 20), and can bind and be inhibited by sclerostin (14, 35). Thus, it is likely that some of sclerostin’s inhibitory effects on bone mass are mediated through binding to and inhibiting LRP6-mediated Wnt signaling. However, the magnitude of sclerostin’s inhibitory effect through LRP6 (versus LRP5) is not known, either in a normal setting or in the setting of loss-of-function mutations in LRP5 (for example, humans with OPPG and Lrp5 knockout mice). We focused on the potential mediatory role of LRP5, rather than LRP6, in exploring sclerostin’s anabolic action on bone because of the prominent role LRP5 appears to play in bone formation (8, 31). The limited data on the in vivo function of LRP6 suggest that it might also be involved in bone resorption (36). Sclerostin inhibition appears to affect both formation and resorption axes in rats, monkeys, and humans (11, 21-23, 37-39), which is consistent with sclerostin’s ability to bind both LRP5 and LRP6. Despite this rationale, it appears from the collective data that LRP6 modulates some of the anabolic action of sclerostin inhibition. This conclusion emerges as one considers that sclerostin antibody and SOST deletion were anabolic in Lrp5 knock-out mice, yet all of the mice in our experiments had fully functional Lrp6 receptors. In support of this point, Chang et al. (40) recently reported that a particular Lrp6-blocking antibody given to a different Lrp5−/−;Sost−/− mouse model was able to completely neutralize the bone overgrowth effects of Sost deletion.

Beyond LRP5 and LRP6, numerous binding partners for sclerostin have been proposed on the basis of in vitro experiments including BMPs, noggin, LRP4, cysteine-rich protein 61, epidermal growth factor receptor–3, alkaline phosphatase, carbonic anhydrase, gremlin-1, fetuin A, midkine, annexin A1 and A2, type I collagen, casein kinase II, and secreted frizzled (Fzd)–related protein 4 (28, 41-45). Of these proposed binding partners, corroborating genetic data exist only for LRP4 (46), and there is strong evidence that LRP4 is an in vivo sclerostin binding partner. LRP4 is not considered to be a core component of the minimal Wnt signaling complex but is thought to act as a facilitator of sclerostin function, possibly acting by presenting sclerostin in such a manner as to facilitate the binding of sclerostin to LRP5 and LRP6. In that role, LRP4 is unlikely to be able to functionally substitute for LRP5. A more parsimonious interpretation of our results would hold that LRP6 can substitute functionally for LRP5 to a greater extent than had been previously appreciated. Quantitative sequencing of mRNA (RNA-seq) recovered from wild-type and Lrp5−/− cortical bone did not reveal a compensatory increase in Lrp6 expression when Lrp5 is absent (24) or when sclerostin is inhibited (table S1). Therefore, the likely reason for SOST/sclerostin depletion increasing bone properties in Lrp5−/− mice is because sclerostin and LRP6 interact differently when LRP5 is absent. That is, in the absence of LRP5, LRP6 might form otherwise rare complexes and/or increased levels of complexes with some combinations of Wnts and Fzds, and/or possibly form reduced levels of complexes with other combinations of Wnts and Fzds with which it would normally interact.

Our study has several limitations. First, the experiments were performed in mice, which are imperfect models of skeletal metabolism for humans. Second, although our results suggest that anti-sclerostin therapy is efficacious in the absence of LRP5, it is unclear whether patients with OPPG will reap benefit from this therapy. This caveat is pertinent considering that both published preclinical studies of in-termittent PTH therapy, conducted in two different mouse models of OPPG, report significant efficacy (9, 47). Yet, human patients with OPPG have inconsistent therapeutic benefit from PTH (6, 7). A similar discrepancy might exist for anti-sclerostin therapy.

Sclerostin is a potent regulator of bone mass. A phase 2 study in post-menopausal osteoporotic women (T score between −2.0 and −3.5) revealed that 1 year of monthly treatments with sclerostin antibody effected a mean BMD increase of 11% at the lumbar spine and 4% at the hip (38). Our data suggest that the skeletal benefits of anti-sclerostin treatment reported from clinical trials might be maintained in OPPG patients, in whom LRP5 is not functional, potentially providing a much-needed anabolic therapy in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The studies undertaken in this communication were designed to reveal whether functional LRP5 receptors are required for the anabolic action of SOST deletion and sclerostin inhibition. LRP5-deficient mice (Lrp5−/−) were rendered (i) Sost-deficient, by genetic deletion of both Sost alleles (Sost−/−), and (ii) sclerostin-inhibited, via treatment with sclerostin antibody. Changes in bone metabolism and anabolic action were measured by numerous assays. All measurements were conducted blinded, using randomized, sample identifiers that gave no indication of group assignment. Each experiment was performed one time. Sample sizes were estimated from BMD effect sizes of Lrp5 and Sost mutant mice we have reported earlier (9, 48). All procedures performed were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Animal husbandry

Genetically engineered mice with mutations in Lrp5 and Sost have been reported previously (9, 49). Briefly, ~90% of the SOST coding sequence and all of the single intron were replaced with a neomycin resistance cassette. For LRP5, exons 7 and 8 were replaced with a neomycin resistance cassette. Neither the targeted Sost nor Lrp5 allele expresses functional mRNA or protein. Sost mutant mice are maintained on a mixed (129/SvJ and Black Swiss) genetic background. Lrp5 mutant mice are maintained on a 129S/J background. Homozygous mutant LRP5 mice (Lrp5−/−) were crossed with homozygous mutant SOST mice (Sost−/−) to produce double heterozygous progeny (Lrp5+/−;Sost+/−). The double heterozygous mice were then intercrossed and only double wild-type (Lrp5+/+;Sost+/+), LRP5 knockout (Lrp5−/−;Sost+/+), SOST knockout mice (Lrp5+/+;Sost−/−), or double-knockout (Lrp5−/−;Sost−/−) offspring were retained. Offspring were same sex–housed in cages of three to five (independent of genotype) and given standard mouse chow [Harlan Teklad 2018SX; 1% Ca; 0.65% P; vitamin D3 (2.1 IU/g)] and water ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with the IACUC guidelines.

Administration of sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII) to adult LRP5 wild-type (Lrp5+/+) and knockout (Lrp5−/−) mice

Seventeen-week-old female mice (Lrp5+/+ or Lrp5−/−) were randomized to receive either twice-weekly subcutaneous injections of either sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII) at 25 mg/kg (37) or vehicle alone for the next 3 weeks (n = 8 mice per genotype and treatment group). Scl-AbIII doses were adjusted weekly on the basis of body mass measurement. Animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation when 20 weeks old.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

DEXA measurements were obtained on isoflurane-anesthetized mice in the prone position with limbs outstretched using PIXImus II (GE Lunar) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. For the genetic experiments, scans were collected every other week from 4.5 until 16.5 weeks of age. Immediately after the final scan, these mice were euthanized via CO2 inhalation for skeletal element recovery. For the mice receiving Scl-AbIII/vehicle treatment, scans were obtained 3 days before therapy was started (that is, 16.5 weeks of age) and at 20 weeks of age, immediately before euthanasia. aBMD and BMC were determined for the post-cranial skeleton.

Micro–computed tomography

After euthanasia, the right femur was dissected from each mouse, fixed for 2 days in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and then transferred into 70% ethanol for μCT scanning (and subsequent analysis; see below). A 2.6-mm span of the distal femoral metaphysis was scanned on a desktop μCT (mCT 20; Scanco Medical AG) at 13-μm resolution using 50-kV peak tube potential and 151-ms integration time to measure trabecular three-dimensional morphometric properties as previously described (48). The following parameters were calculated from each reconstructed slice stack through the metaphysis: bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular BMC (Tb.BMC). Twenty mCT slices were collected from the midshaft femur using 9-μm resolution to measure cortical areal and geometric properties. Midshaft femur slices were imported into ImageJ [National Institutes of Health (NIH)] to measure the total area within the periosteal border and the area between the periosteal and endocortical surfaces.

Fluorochrome administration and bone quantitative histomorphometry

Mice in the genetic experiments were given oxytetracycline HCl (80 mg/kg, subcutaneously) at 5 weeks of age, calcein (12 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) at 8 weeks of age, and alizarin complexone (20 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) at 12 weeks of age. Mice receiving antibody were given calcein (12 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) after 1 week of therapy (that is, when 18 weeks old) and alizarin complexone (20 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) after 2 weeks of therapy (when 19 weeks old). After euthanasia and μCT scanning (see above) of the right femur, the bone was dehydrated in graded ethanols and embedded nondecalcified in methylmethacrylate. Midshaft femur sections were cut in the transverse plane (~200 μm thick) using a diamond-embedded wafering saw (Buehler Inc.) and ground to a final thickness of ~30 μm. Distal femur sections were cut in the longitudinal plane with a motorized microtome (Leica 2255; Leica Microsystems Inc.). Periosteal bone formation parameters were calculated by measuring the extent of unlabeled perimeter, single-labeled perimeter (sL.Pm), double-labeled perimeter (dL.Pm), and the area between the double labeling with the Bioquant Osteo system (Bioquant Corp.). Derived histomorphometric parameters, including MS/BS (%), MAR (μm/day), and BFR/BS (μm3/μm2 per year), were calculated using standard procedures (50). Osteoblast- and osteoclast-covered surfaces were measured in the distal femur secondary spongiosa from MacNeal/von Kossa– and Trap-stained sections, respectively, as previously described (31).

Biomechanical measurements of whole-bone strength

The left femur was collected from each euthanized mouse, wrapped in saline-soaked gauze, and frozen at −20°C until the day of testing. Once femurs had been collected from all mice, they were equilibrated at room temperature in a saline bath for 5 hours before mechanical testing. Measures of whole-bone strength were obtained on femurs positioned posterior side down across two lower supports (spaced 9 mm apart) of a three-point bending apparatus. The fixtures were mounted in the frame of a Bose ElectroForce 3200 electromagnetic test instrument, which has a force resolution of 0.001 N (51). Each femur was loaded to failure in monotonic compression using a crosshead speed of 0.2 mm/s, during which force and displacement measurements were collected every 0.01 s. From the force versus displacement curves, ultimate force, yield force, stiffness, and energy to failure were calculated using standard equations (52).

Quantitative sequencing of mRNA from Scl-AbIII–treated mice

Ten-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were given twice-weekly subcutaneous injections of Scl-AbIII (25 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) and then euthanized at 12 weeks old by CO2 inhalation. RNA was recovered from each tibial cortex with the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina) and was used to create an individual bar-coded RNA sequencing library as previously described (24). Nine separate libraries were pooled per single line of 50–base pair paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2000. Library-specific paired reads were mapped to the mouse genome (mm9) with RUM. The expression level of each gene was determined on the basis of the number of reads aligned to the exons and normalization of the read counts with respect to the total number of mapped reads and the dispersion in the distribution of these reads [see (24) for details].

Detection of changes in protein abundance using immunohistochemistry

Proximal tibias from the experimental mice were decalcified in 10% EDTA and processed for paraffin sectioning. Five-micrometer-thick sections were cut and incubated in citrate buffer [10 mM citric acid, 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 6.0)] for 1 hour at 65°C to unmask antigens, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with a rabbit polyclonal p-Smad 1/5/8 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Subsequent processing and secondary labeling were performed with the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories), followed by the 3′-diaminobenzidine peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) reaction to produce a detectable chromagen. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. With Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics) software, the numbers of p-Smad 1/5/8– positive osteocytes (brown cells) and p-Smad 1/5/8–negative osteocytes (purple cells) were manually counted in the proximal tibia cortex and were expressed as a ratio of positive to total osteocytes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were computed with JMP (version 4.0, SAS Institute Inc.). The radiographic, histomorphometric, and biomechanical endpoints were analyzed using one- or two-way ANOVA, with geno-type and/or antibody treatment as main effects. Time series data were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA. When at least one main effect was significant, interactions terms were calculated and tested for significance. Differences among groups were tested for significance with Fisher’s PLSD post hoc test. Significant differences in gene expression (RNA-seq) between each treatment group were determined with Fisher’s exact test, followed by correction for multiple hypothesis testing, and the elimination of outlier samples and animals with leave-one-out cross-validation. Differences in p-Smad staining from immuno-histochemical analyses were tested with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the case of two groups (wild type versus Sost−/−) or with the Kruskal-Wallis test in the case of more than two groups (wild type and Lrp5−/− treated ± Scl-AbIII). Statistical significance was taken at P < 0.05. Two-tailed distributions were used for all analyses. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Body mass in mutant Lrp5 and Sost female and male mice.

Fig. S2. Photomicrographs of MacNeal/von Kossa–stained sections from the distal femur of Sost/Lrp5 mutant male mice.

Fig. S3. Photomicrographs of MacNeal/von Kossa–stained sections from the distal femur of wild-type and Lrp5−/− mice that were treated for 3 weeks with vehicle (saline) or sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII).

Fig. S4. Photomicrographs of the growth plate and primary spongiosa (upper panels) and the cortex (lower panels) from the proximal tibia of 15-week-old wild-type and Sost−/− mice that were immunolabeled for p-Smad 1/5/8 (brown staining) and counterstained with hematoxylin (purple staining).

Collection of genes whose expression is different by twofold or more (in either direction) after 2 weeks of Scl-AbIII treatment versus vehicle treatment in 10-week-old wild-type mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Condon and E. Pacheco for assistance with paraffin sectioning.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grant AR53237 and Veterans Affairs grant BX001478 (to A.G.R.), NIH grant AR62326 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to M.L.W.), and the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Foundation (to C.M.J.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/5/211/211ra158/DC1

Competing interests:

C.P. is an Amgen Inc. employee and shareholder. The remaining authors have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Raw sequence data from the RNA-seq experiments are available at the NIH Short Reads Archive. Sost knockout mice and sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII) were provided by Amgen Inc. and UCB Pharma.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Becker DJ, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA. The societal burden of osteoporosis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2010;12:186–191. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0097-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins J, Aragaki AK, Kooperberg C, Watts N, Wactawski-Wende J, Jackson RD, LeBoff MS, Lewis CE, Chen Z, Stefanick ML, Cauley J. Factors associated with 5-year risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2007;298:2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong Y, B. Slee R, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S, Reginato AM, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux FH, Lev D, Zacharin M, Oexle K, Marcelino J, Suwairi W, Heeger S, Sabatakos G, Apte S, Adkins WN, Allgrove J, Arslan-Kirchner M, Batch JA, Beighton P, Black GC, Boles RG, Boon LM, Borrone C, Brunner HG, Carle GF, Dallapiccola B, De Paepe A, Floege B, Halfhide ML, Hall B, Hennekam RC, Hirose T, Jans A, Jüppner H, Kim CA, Keppler-Noreuil K, Kohlschuetter A, LaCombe D, Lambert M, Lemyre E, Letteboer T, Peltonen L, Ramesar RS, Romanengo M, Somer H, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Steinmann B, Sullivan B, Superti-Furga A, Swoboda W, van den Boogaard MJ, Van Hul W, Vikkula M, Votruba M, Zabel B, Garcia T, Baron R, Olsen BR, Warman ML. Osteoporosis-Pseudoglioma Syndrome Collaborative Group, LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001;107:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saarinen A, Saukkonen T, Kivelä T, Lahtinen U, Laine C, Somer M, Toiviainen-Salo S, Cole WG, Lehesjoki AE, Mäkitie O. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) mutations and osteoporosis, impaired glucose metabolism and hypercholesterolaemia. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010;72:481–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arantes HP, Barros ER, Kunii I, Bilezikian JP, Lazaretti-Castro M. Teriparatide increases bone mineral density in a man with osteoporosis pseudoglioma. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:2823–2826. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streeten EA, McBride D, Puffenberger E, Hoffman ME, Pollin TI, Donnelly P, Sack P, Morton H. Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome: Description of 9 new cases and beneficial response to bisphosphonates. Bone. 2008;43:584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato M, Patel MS, Levasseur R, Lobov I, Chang BH, Glass DA, II, Hartmann C, Li L, Hwang TH, Brayton CF, Lang RA, Karsenty G, Chan L. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:303–314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawakami K, Robling AG, Ai M, Pitner ND, Liu D, Warden SJ, Li J, Maye P, Rowe DW, Duncan RL, Warman ML, Turner CH. The Wnt co-receptor LRP5 is essential for skeletal mechanotransduction but not for the anabolic bone response to parathyroid hormone treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:23698–23711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmen SL, Giambernardi TA, Zylstra CR, Buckner-Berghuis BD, Resau JH, Hess JF, Glatt V, Bouxsein ML, Ai M, Warman ML, Williams BO. Decreased BMD and limb deformities in mice carrying mutations in both Lrp5 and Lrp6 . J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19:2033–2040. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Warmington KS, Niu QT, Asuncion FJ, Dwyer D, Grisanti M, Han C-Y, Kostenuik PJ, Stolina M, Ominsky MS, Ke HZ. Increased bone mass and bone strength by sclerostin antibody is maintained by a RANKL inhibitor in ovariectomized rats with established osteopenia. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27(Suppl. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Lierop AH, Hamdy NA, van Egmond ME, Bakker E, Dikkers FG, Papapoulos SE. Van Buchem disease: Clinical, biochemical, and densitometric features of patients and disease carriers. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;28:848–854. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourhis E, Wang W, Tam C, Hwang J, Zhang Y, Spittler D, Huang OW, Gong Y, Estevez A, Zilberleyb I, Rouge L, Chiu C, Wu Y, Costa M, Hannoush RN, Franke Y, Cochran AG. Wnt antagonists bind through a short peptide to the first b-propeller domain of LRP5/6. Structure. 2011;19:1433–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Zhang Y, Kang H, Liu W, Liu P, Zhang J, Harris SE, Wu D. Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19883–19887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balemans W, Piters E, Cleiren E, Ai M, Van Wesenbeeck L, Warman ML, Van Hul W. The binding between sclerostin and LRP5 is altered by DKK1 and by high-bone mass LRP5 mutations. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2008;82:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenov MV, He X. LRP5 mutations linked to high bone mass diseases cause reduced LRP5 binding and inhibition by SOST. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38276–38284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semënov M, Tamai K, He X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26770–26775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellies DL, Viviano B, McCarthy J, Rey JP, Itasaki N, Saunders S, Krumlauf R. Bone density ligand, Sclerostin, directly interacts with LRP5 but not LRP5G171V to modulate Wnt activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1738–1749. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joeng KS, Schumacher CA, Zylstra-Diegel CR, Long F, Williams BO. Lrp5 and Lrp6 redundantly control skeletal development in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 2011;359:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald BT, Semenov MV, Huang H, He X. Dissecting molecular differences between Wnt coreceptors LRP5 and LRP6. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ominsky MS, Li C, Li X, Tan HL, Lee E, Barrero M, Asuncion FJ, Dwyer D, Han CY, Vlasseros F, Samadfam R, Jolette J, Smith SY, Stolina M, Lacey DL, Simonet WS, Paszty C, Li G, Ke HZ. Inhibition of sclerostin by monoclonal antibody enhances bone healing and improves bone density and strength of nonfractured bones. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:1012–1021. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian X, Jee WS, Li X, Paszty C, Ke HZ. Sclerostin antibody increases bone mass by stimulating bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption in a hindlimb-immobilization rat model. Bone. 2011;48:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian X, Setterberg RB, Li X, Paszty C, Ke HZ, Jee WS. Treatment with a sclerostin antibody increases cancellous bone formation and bone mass regardless of marrow composition in adult female rats. Bone. 2010;47:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayturk UM, Jacobsen CM, Christodoulou DC, Gorham J, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Robling AG, Warman ML. An RNA-seq protocol to identify mRNA expression changes in mouse diaphyseal bone: Applications in mice with bone property altering Lrp5 mutations. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:2081–2093. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lev D, Binson I, Foldes AJ, Watemberg N, Lerman-Sagie T. Decreased bone density in carriers and patients of an Israeli family with the osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2003;5:419–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahnazari M, Wronski T, Chu V, Williams A, Leeper A, Stolina M, Ke HZ, Halloran B. Early response of bone marrow osteoprogenitors to skeletal unloading and sclerostin antibody. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2012;91:50–58. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spatz JM, Ellman R, Cloutier AM, Louis L, van Vliet M, Suva LJ, Dwyer D, Stolina M, Ke HZ, Bouxsein ML. Sclerostin antibody inhibits skeletal deterioration due to reduced mechanical loading. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:865–874. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkler DG, Sutherland MK, Geoghegan JC, Yu C, Hayes T, Skonier JE, Shpektor D, Jonas M, Kovacevich BR, Staehling-Hampton K, Appleby M, Brunkow ME, Latham JA. Osteocyte control of bone formation via sclerostin, a novel BMP antagonist. EMBO J. 2003;22:6267–6276. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winkler DG, Sutherland MS, Ojala E, Turcott E, Geoghegan JC, Shpektor D, Skonier JE, Yu C, Latham JA. Sclerostin inhibition of Wnt-3a-induced C3H10T1/2 cell differentiation is indirect and mediated by bone morphogenetic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2498–2502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babij P, Zhao W, Small C, Kharode Y, Yaworsky PJ, Bouxsein ML, Reddy PS, Bodine PV, Robinson JA, Bhat B, Marzolf J, Moran RA, Bex F. High bone mass in mice expressing a mutant LRP5 gene. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003;18:960–974. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Y, Niziolek PJ, MacDonald BT, Zylstra CR, Alenina N, Robinson DR, Zhong Z, Matthes S, Jacobsen CM, Conlon RA, Brommage R, Liu Q, Mseeh F, Powell DR, Yang QM, Zambrowicz B, Gerrits H, Gossen JA, He X, Bader M, Williams BO, Warman ML, Robling AG. Lrp5 functions in bone to regulate bone mass. Nat. Med. 2011;17:684–691. doi: 10.1038/nm.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laine CM, Chung BD, Susic M, Prescott T, Semler O, Fiskerstrand T, D’Eufemia P, Castori M, Pekkinen M, Sochett E, Cole WG, Netzer C, Mäkitie O. Novel mutations affecting LRP5 splicing in patients with osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:875–881. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayram F, Tanriverdi F, Kurtoğlu S, Atabek ME, Kula M, Kaynar L, Keleştimur F. Effects of 3 years of intravenous pamidronate treatment on bone markers and bone mineral density in a patient with osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG) J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;19:275–279. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2006.19.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tüysüz B, Bursalu̇ A, Alp Z, Suyugül N, Laine CM, Mäkitie O. Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome: Three novel mutations in the LRP5 gene and response to bisphosphonate treatment. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2012;77:115–120. doi: 10.1159/000336193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holdsworth G, Slocombe P, Doyle C, Sweeney B, Veverka V, Le Riche K, Franklin RJ, Compson J, Brookings D, Turner J, Kennedy J, Garlish R, Shi J, Newnham L, McMillan D, Muzylak M, Carr MD, Henry AJ, Ceska T, Robinson MK. Characterization of the interaction of sclerostin with the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) family of Wnt co-receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:26464–26477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.350108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubota T, Michigami T, Sakaguchi N, Kokubu C, Suzuki A, Namba N, Sakai N, Nakajima S, Imai K, Ozono K. Lrp6 hypomorphic mutation affects bone mass through bone resorption in mice and impairs interaction with Mesd. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:1661–1671. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS, Morony S, Gong J, Cao J, Gao Y, Shalhoub V, Tipton B, Haldankar R, Chen Q, Winters A, Boone T, Geng Z, Niu QT, Ke HZ, Kostenuik PJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Paszty C. Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009;24:578–588. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClung MR, Grauer A, Boonen S, Brown JP, Diez-Perez A, Langdahl B, Reginster J-Y, Zanchetta JR, Katz L, Maddox J, Yang Y-C, Libanati C, Bone HG. Inhibition of sclerostin with AMG 785 in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density: Phase 2 trial results. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27(Suppl. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Padhi D, Jang G, Stouch B, Fang L, Posvar E. Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:19–26. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang MK, Kramer I, Keller H, Gooi JH, Collett C, Jenkins D, Ettenberg SA, Cong F, Halleux C, Kneissel M. Reversing LRP5-dependent osteoporosis and SOST-deficiency induced sclerosing bone disorders by altering WNT signaling activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2059. 10.1002/jbmr.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi HY, Dieckmann M, Herz J, Niemeier A. Lrp4, a novel receptor for Dickkopf 1 and sclerostin, is expressed by osteoblasts and regulates bone growth and turnover in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig TA, Bhattacharya R, Mukhopadhyay D, Kumar R. Sclerostin binds and regulates the activity of cysteine-rich protein 61. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;392:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craig TA, Kumar R. Sclerostin–erbB-3 interactions: Modulation of erbB-3 activity by sclerostin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;402:421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devarajan-Ketha H, Craig TA, Madden BJ, Robert Bergen H, III, Kumar R. The sclerostin-bone protein interactome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;417:830–835. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkler DG, Yu C, Geoghegan JC, Ojala EW, Skonier JE, Shpektor D, Sutherland MK, Latham JA. Noggin and sclerostin bone morphogenetic protein antagonists form a mutually inhibitory complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36293–36298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leupin O, Piters E, Halleux C, Hu S, Kramer I, Morvan F, Bouwmeester T, Schirle M, Bueno-Lozano M, Fuentes FJ, Itin PH, Boudin E, de Freitas F, Jennes K, Brannetti B, Charara N, Ebersbach H, Geisse S, Lu CX, Bauer A, Van Hul W, Kneissel M. Bone overgrowth-associated mutations in the LRP4 gene impair sclerostin facilitator function. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:19489–19500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwaniec UT, Wronski TJ, Liu J, Rivera MF, Arzaga RR, Hansen G, Brommage R. PTH stimulates bone formation in mice deficient in Lrp5. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:394–402. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robling AG, Kedlaya R, Ellis SN, Childress PJ, Bidwell JP, Bellido T, Turner CH. Anabolic and catabolic regimens of human parathyroid hormone 1–34 elicit bone- and envelope-specific attenuation of skeletal effects in Sost-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2963–2975. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Ominsky MS, Niu QT, Sun N, Daugherty B, D’Agostin D, Kurahara C, Gao Y, Cao J, Gong J, Asuncion F, Barrero M, Warmington K, Dwyer D, Stolina M, Morony S, Sarosi I, Kostenuik PJ, Lacey DL, Simonet WS, Ke HZ, Paszty C. Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:860–869. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: Standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niziolek PJ, Farmer TL, Cui Y, Turner CH, Warman ML, Robling AG. High-bone-mass-producing mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway result in distinct skeletal phenotypes. Bone. 2011;49:1010–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner CH, Burr DB. Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: A tutorial. Bone. 1993;14:595–608. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90081-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Body mass in mutant Lrp5 and Sost female and male mice.

Fig. S2. Photomicrographs of MacNeal/von Kossa–stained sections from the distal femur of Sost/Lrp5 mutant male mice.

Fig. S3. Photomicrographs of MacNeal/von Kossa–stained sections from the distal femur of wild-type and Lrp5−/− mice that were treated for 3 weeks with vehicle (saline) or sclerostin antibody (Scl-AbIII).

Fig. S4. Photomicrographs of the growth plate and primary spongiosa (upper panels) and the cortex (lower panels) from the proximal tibia of 15-week-old wild-type and Sost−/− mice that were immunolabeled for p-Smad 1/5/8 (brown staining) and counterstained with hematoxylin (purple staining).

Collection of genes whose expression is different by twofold or more (in either direction) after 2 weeks of Scl-AbIII treatment versus vehicle treatment in 10-week-old wild-type mice.