Abstract

In this article, we use a phenomenology framework to explore emerging adults’ formative experiences of family stress. Fourteen college students participated in a qualitative interview about their experience of family stress. We analyzed the interviews using the empirical phenomenological psychology method. Participants described a variety of family stressors, including parental conflict and divorce, physical or mental illness, and emotional or sexual abuse by a family member. Two general types of parallel processes were essential to the experience of family stress for participants. First, the family stressor was experienced in shifts and progressions reflecting the young person’s attempts to manage the stressor, and second, these shifts and progressions were interdependent with deeply personal psychological meanings of self, sociality, physical and emotional expression, agency, place, space, project, and discourse. We describe each one of these parallel processes, and their subprocesses, and conclude with implications for mental health practice and research.

Keywords: families, lived experience, phenomenology, stress/distress, young adults

In the United States and other industrialized nations, the majority of emerging adults between 18 and 25 years of age are now pursuing a higher education and postponing marriage and parenting by about 10 years, relative to previous decades (Arnett, 2004). This period of development can be exciting for emerging adults who exercise growing freedom to pursue a career and varied relationships (Shanahan, 2000). Conversely, emerging adults also face growing demands to navigate through the uncertainty of work and relationships that can bring about much anxiety and identity confusion (Arnett, 2004; Dyson & Renk, 2006).

Adjustment during this period is largely shaped by formative experiences in childhood and adolescence, many of which occur in the family (Shanahan, 2000). The family acts as a source of belonging and connection, regulator of emotions, enforcer of social norms, and source of individuation for youth (Masten & Shaffer, 2006). Stressors can disrupt these functions and have a lasting impact on children’s identity formation, and subsequently on their orientation to adult roles (Friedlander, Reid, Shupak, & Cribbie, 2007). Emerging adults who struggle to meet academic and work demands are at high risk for college dropout, academic failure, and mental health concerns, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Dyson & Renk, 2006). Health care professionals should be prepared to support this vulnerable population, by understanding the role of the family in emerging adults’ need for autonomy and adaptation to life demands.

The literature on emerging adults and the family is scant in large part because of a common, yet erroneous belief that as emerging adults leave home for college, they move toward psychological emancipation from the family. The continued interdependence of the emerging adult with the family remains critical to adjustment during the college years because both autonomy and connectedness facilitate individuation (Aquilino, 2006; Friedlander et al., 2007; McLean, Breen, & Fournier, 2006). In this article, we use qualitative methods to explore the essential processes underlying emerging adults’ lived experience of formative family stress. We propose a model of family stress to inform research and practice with emerging adults.

The Lasting Influence of the Family in Emerging Adulthood

The lasting influence of family life on emerging adults is best explained by “how families conduct themselves and interact in the familiar everyday surroundings of their own households” (Kantor & Lehr, 1975, as cited in Fiese & Spagnola, 2006, p.119). Family life is guided by stabilizing forces such as clear roles and expectations, routines, a positive emotional climate, and traditions and beliefs (Fiese & Spagnola, 2006). These forces, combined with children’s internal adaptive resources, e.g., self-esteem, lay a foundation for resilience across the lifespan (Luecken & Gress, 2010). When early and repeated disruptions in stabilizing family forces occur, children face significant stress in the family and they develop incoherent images of family life that shape their personal world and the way they respond to their social world (Boss, 2003). Hence, these stressful experiences can be formative in the lives of individuals (Fiese & Spagnola, 2006).

The most widely acceptable definition of family stress consists of a crisis that occurs in response to an event, where the magnitude of the crisis is a function of the family’s existing resources, and the meaning attached to the event (Boss, 2003). Family stressors are often aggregate and have cumulative effects on children’s development (Masten & Shaffer, 2006). For example, parental divorce might be preceded by marital conflict and hostile parent-child interactions, and followed by stressors associated with single parenting. Parents affected by family stress might be less able to provide a stimulating environment, demonstrate warmth, and deliver consistent discipline and monitoring (Valdez, Mills, Barrueco, Leis, & Riley, 2011); in turn, the parent-child relationship becomes increasingly conflicted (Shanahan, 2000). Thus, to develop effective developmentally-appropriate interventions for emerging adults, it is critical to capture the totality and complexity of the lived experience when studying family stress.

Family stress and its deleterious consequences on parenting competence and parent-child bonds have been linked to children’s challenges in developmentally-salient tasks, such as peer relationships, academics, and regulation of behavior and emotion (Luecken & Gress, 2010). By limiting the development of adaptive coping strategies, family stress has also been linked to early transitions to adulthood including undertaking parenting roles during childhood, leaving home early, and teenage pregnancy (Luecken & Gress, 2010). In addition, family stress stifles individuation, the psychological autonomy to explore interpersonal relationships and occupational roles, increasing risk of depression and decreasing self-esteem and personal efficacy in emerging adulthood (Aquilino, 2006; Friedlander et al., 2007).

For many emerging adults who experience family stress during childhood or adolescence, entering college means breaking free from the chaotic and dysfunctional relationships from home (Arnett, 2004). Family relationships can improve because emerging adults are no longer exposed to the stressful home environment and are able to gain a new perspective on their family dynamics (Arnett, 2004; Shanahan, 2000). However, families may discourage emerging adults’ autonomy, which may constrain their relationships in college (Aquilino, 2006; Arnett, 2004; Luecken & Gress, 2010). Finally, preoccupation with the family’s well-being might limit emerging adults’ sense of efficacy in college, further affecting their academic efforts (Friedlander et al., 2007). Thus, more and more students will be at risk of failing college if greater attention is not dedicated to addressing their potentially stressful family contexts.

Theoretical Framework

In this article we are influenced by the Double ABC-X (McCubbin & Patterson, 1982) family stress model that explains adaptation to a family stressor (X) as influenced by the stressor (A) in combination with family coping resources (B) and meanings (C) assigned to the stressor. On adaptation or management of a previous stressor, the family starts out with a new baseline (Double A) as aspects of the previous stressor might be unresolved and family membership and roles might have changed as a consequence of family members’ efforts to cope with the original stressor (Price, Price, & McKenry, 2010). There are two types of family resources (Double B), the original resources set in place to cope with the original stressor and coping resources that were strengthened or developed in response to the original stressor. The family forms a representation of the new stressor and the cumulative effects from previous stressors and the meaning attach to the totality of the family’s experience (Double C; Price et al., 2010). Finally, the family is faced with an evolving stress response and subsequent adaptation (Double X).

None of the studies examining the Double ABC-X model are with emerging adults. Across the majority of studies, representation of the stressor was the primary process predicting adaptation (Lee & Iverson-Gilbert, 2003; Pittman & Bowen, 1994). Representation of stressful events appears to both be consistent over time with respect to the psychological meanings contained within those representations (McAdams et al., 2006) and to be constructed in relation to the present and future self (McLean et al., 2010). Thus, we can gain a deeper understanding of how emerging adults’ representations about stressful family experiences shape their adaptation.

We adopt a theoretical model of phenomenology to studying family stress. Phenomenology posits that family stress, like any human experience, is a psychological phenomenon (Ashworth, 2003). When individuals experience changes in their life that are outside of their control, their lived experience or lifeworld is altered. The lifeworld is a constellation of implicit psychological meanings and assumptions about relations to the world, fundamental to the human experience, and actualized distinctly through individuals’ personal and “temporal relationships with others and with their own set of projects” (Ashworth, 2003, p. 146). The lifeworld is centered on one’s own identity or sense of agency and presence; sociality or comfort in social relations; embodiment or emotional and physical expression; temporality or sense of past, present, and future; spatiality or context; project or ability to carry out desired activities; and discourse or language used to describe lived experiences (Ashworth, 2003). The lifeworld serves as a heuristic for investigating phenomena and should be viewed holistically, rather than separately, to obtain a greater sense of a lived experience (Ashworth, 2003).

Extending current models of family stress, we focus on individuals’ formative experience within the family. The formative experience has a lasting influence on adaptation over time, based on the family’s management of the stressful experience and the individual’s psychological meanings about the experience. We focus on family stress as a category, rather than a specific event such as parental divorce, because family stressors are cumulative, interrelated, and cannot be studied in isolation from the rest of family life (Masten & Shaffer, 2006). As emerging adults often present to health care settings with a history of interrelated family stressors, our broad focus on family stress is well-suited to inform practice and shape future research with this vulnerable, yet understudied, population (Arnett, 2004).

Method

Methodology

In this article, we used empirical phenomenological psychology (EPP; Fischer & Wertz, 2002; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003; Wertz, 2005) to explore essential lived experiences of family stress in the emerging adult population. The lived experience is made up of (a) processes describing shifts and progressions in the experience, and (b) implicit, taken-for-granted psychological meanings, the lifeworld, that are universal and altered by experience (Wertz, 2005). In EPP, the researcher asks participants to describe in detail an experience to be understood psychologically, such as family stress, as the researcher engages in a reductionist process to capture the essence of that experience. This is comprehensively illustrated in later sections. The EPP method is called “empirical” because it has clear, widely published guidelines for collecting and analyzing the data, lending itself to reproducibility (Fischer & Wertz, 2002; Wertz, 2005).

Participants

We used purposeful sampling to select information-rich cases that provided in-depth understanding rather than empirical generalizations about emerging adults’ lived experience of family stress. Because a significant number of emerging adults are pursuing a higher education (Arnett, 2004) and an alarming number of these adults are at risk for academic and mental health difficulties (Friedlander et al., 2007), we selected participants 18–25 years of age from a Midwest university who reported a history of family stress.

The Institutional Review Board of the authors’ university approved all study procedures and safeguards. Participants who were enrolled in an undergraduate psychology course on interviewing and survey methods (n = 61) during Fall 2007 consented to the study in writing. Participants completed a screening survey developed by the authors about family psychiatric history, coping, and stressful family events. Seventy percent of participants (n = 43) reported a history of family stress on the screener (based on the item, “Please identify a situation or event that was stressful in your family”) and were contacted in Spring 2008 to participate in interviews about their experience. Of the 43 participants, 27 (63%) agreed to participate in interviews, and complete recordings were available for 21 participants. During the analysis stage, we found that only 15 participants described a clear family stressor(s) and provided particularly rich, thick, descriptions about family stress (Hubberman & Miles, 2002).

We did not find new themes from additional cases after 14 participants, constituting the final sample of this article. The 14 interviewed participants ranged in age between 20–23 years (X = 21.21, SD = .70). The majority of participants interviewed self- reported as White (64%), women (93%), heterosexual (86%), and college seniors (86%). In terms of parental education, 83% of participants’ fathers and 64% of their mothers had earned a college degree. No differences were found between the final sample and the original sample of 61 participants with respect to any demographic characteristic.

Interviews

Our semistructured interviews consisted of broad questions regarding family stress: “Tell me about a major stressful experience in your family,” “How did the experience affect you.” “How did your relationship with your family change as a result of this experience,” and “How did you get through this experience?” We explored multiple stressors in terms of their onset, duration, and impact on the person. Audiotaped interviews lasted 90–120 minutes and took place in a confidential office on campus. Interviewers later transcribed each interview verbatim. Two participants were re-interviewed over the phone to clarify details provided in the first interview.

Data Analysis

Our group had prior experience with qualitative methods, and received additional training and consultation in phenomenology. Carmen Valdez also had past research experience with family stress. First, we read and reread the transcripts maintaining the philosophical stance of epoché, or suspension of judgment, to gain an understanding of the whole of the experience of each participant from a non theoretical viewpoint and to immerse ourselves in the lived world of the participant through a deep empathic process (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003; Wertz, 2005).

Second, we reread the transcripts and marked meaning units as they applied to our question (Wertz, 2005). Third, we read and rewrote meaning units to capture their essential elements (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). This process was done by engaging in free imaginative variation, a process through which we determined which components of the phenomena were essential to the whole experience and which were not, such as “Does family stress change with variation of X component?”

Fourth, given that our participants did not usually describe their daily experiences in a linear fashion, we organized meaning units in temporal sequence to allow the reader to vividly immerse themselves in the shifts and progressions of persons’ lived experiences (Worthen & McNeill, 1996). We preserved the language used by participants as much as possible in each sequenced synopsis. Fifth, we created categories and classed them as essential to the experience of family stress if at least 75% of participants mentioned them. We arrived at final representative themes from these categories by consensus.

Following this step, we created a general psychological structure to more fully derive the lived psychological experience of family stress (Fischer & Wertz, 2002). This structure was guided by participants’ lifeworld features as related to how the family stress affects a person’s (a) identity and sense of agency, (b) relations with others, (c) own body, including emotions, (d) sense of time and biography, (e) use of space and place in daily life, (f) ability to carry out desired activities, and (g) discourse about the situation (Ashworth, 2003).

We established trustworthiness (Hubberman & Miles, 2002) through triangulation of the literatures in emerging adulthood and family stress. We coded each interview separately and met to compare themes to ensure consensus and to establish a common base for additional analysis of remaining transcripts. During team meetings we discussed our personal expectations about the study to be aware of their influence on data analysis and interpretation. An external auditor reviewed the individual transcripts and the final themes to confirm the fit of the data to the findings and the researchers’ bracketing of biases. Finally, we included thick descriptions in the results section to allow readers to compare and contrast their own perspectives to the authors’.

Results

Consistent with EPP, we illustrated themes in a present-tense, factual/phenomenal form, e.g., “persons cope with…,” to closely parallel the lived experience while generalizing across interviews (Fischer & Wertz, 2002). We grounded the themes in participants’ concrete descriptions with quotes. We also used the term “young person” (as opposed to “emerging adult”) when referring to participants during childhood or adolescence.

We organized our themes around two overarching domains. In the first domain we referred to seven essential shifts and progressions identified in participants’ stories related to life prior to, during, and after the stressor. In the second domain we referred to the deeply personal psychological meanings about these processes that reflect an altered lifeworld: their sense of self, sociality, embodiment, agency, place, space, project, and discourse. We present these two domains and their subdomains in an integrated manner to illustrate their interdependence.

Prior Experiences and Existing Resources

This theme refers to the family experiences preceding the onset or intensification of a formative stressful experience. Although a few emerging adults recall this period as stress-free for the family, the majority of emerging adults recall a series of early, often precipitating stressors in their family life. These early stressors often intensify or foretell the onset of a major family stressor as in the case of frequent marital arguments related to the father’s drinking problem that led to divorce: “[Dad] had gone to rehab … and nothing was helping and my mom had kicked him out and finally she was like, ‘It’s not worth trying to keep the marriage together.’” Although this emerging adult identifies her parents’ divorce as the formative stressor in her life, family life prior to her parents’ divorce is marked by a discourse of unpredictability and burden that foreshadows the family’s separation from an impaired family member.

Early on, the emerging adult looks for signs of normalcy, suggesting the desire for family life to improve. An emerging adult reflecting on her brother’s early signs of mental illness recalls how she made meaning of his behavior as a mere difficult transition:

He never really slept, which, you know he was a teenager so we figured that was normal and he couldn’t really focus on a lot of things, we thought it was ADHD, or something like that where we gave him Ritalin. Hindsight being 20–20, he was always kind of more aggressive than most kids … so that should have been a thing we saw coming.

In addition to earlier attempts at normalizing her brother’s behavior, this quote illustrates a common experience among emerging adults, that of owning and disowning the stressor and a “we” versus “they” duality in which the family both separates from a challenging family member and yet assumes a collective responsibility for this person.

Formative Family Stressor

A shift in the experience comes when the young person experiences a major family stressor that typically takes place during childhood or adolescence and that continues into emerging adulthood. Family stressors include a debilitating physical or mental illness in a family member; alcoholism and impaired functioning in a parent; marital infidelity and discord; marital separations or divorce; a parent’s imprisonment; sexual, physical, and/or emotional abuse by a family member; and sexual orientation disclosure of child or parent. A multiracial emerging adult recalls the painful memory of her mother’s abusive behavior beginning in adolescence:

After [the shootings at] Virginia Tech my mom got upset with me [about not paying the cell phone bill] and when she hung up the phone, she told my sister, “Why couldn’t she be one of the [dead] students at Virginia Tech?” Then she called me an ignorant and inconsiderate [racial slur] on top of that, so I didn’t talk to her for weeks…. That was one instance more of her abusive language.

This stressful experience is formative because the hostile parent-child interactions destabilize the young person’s sense of security and dignity, subsequently undermining her self-confidence. In addition, this experience counters universal notions of family life, such as parents’ role in protecting and nurturing their children. This emerging adult asks, “How could it be that a parent could wish such bad on her own child?” Sociality and spatiality are disrupted in that her mother and home fail to provide the nurturance needed to thrive.

For the majority of young persons, the stressor has an insidious onset signaling intensification of a related stressor. Although many young persons expect the family stressor to take place, they are still taken aback by its personal impact. An emerging adult explains how her father’s drunk-driving homicide was of no surprise, but burdensome nonetheless:

When he used to pick us up to go visit his house he’d be drinking and driving then. There’d be times when we would get half way back to my dad’s house and he’d be too drunk to even be driving, so then my older brother, who was not 16 at the time, would drive and take us home. So … I figured [homicide] was bound to happen sometime. I never thought it would affect me this much, though.

A few young persons experience the stressor unexpectedly, as in the case of injury, disclosure of sexual orientation, or illness diagnosis. A few others experience an unexpected stressor following a series of unrelated stressors. One emerging adult recalls his family’s financial struggles forcing them to live with relatives, where he was sexually abused by an uncle.

Some stressors evoke shame among young persons who face judgment from society, as in the case of neighbors looking down on the family for the father’s incarceration. An emerging adult described the shame of her lowered social status as a result of her mother’s illness.

Well I absolutely hated the lunch ticket because I had a different color ticket than everyone else and it was kind of embarrassing because, you know people, even in third grade people understood and it was like, “Oh, you can’t afford lunch.”

Buffering influences on the young person

Existing supports can buffer the onset or intensification of a stressor. When a parent becomes ill or is otherwise unavailable, a positive adult figure often assumes care of the family, nurturing the young person’s self:

When it got too stressful at home I would go to [my grandma’s] house next door and me and my grandma bonded a lot. We would make cookies and make dinner and she would teach me about home making, sewing, and planting a garden, and so that was really good.

In other cases, this adult figure is absent or is unable to buffer the negative effects of the stressor. The emerging adult recalls at times being betrayed or abandoned by the “healthy” parent, as when a father is overly involved in work while the mother is diagnosed with a mental illness. The following quote of an emerging adult whose father was violent and an alcoholic reflects the mother’s additional victimization of the young person:

My mom blamed me for my sister going on antidepressants, she said [my sister] and I would pick on each other and that was my fault and um, it was my fault that the family argued, it was my fault that my dad would get to be as mean as he would sometimes get when he was drinking without us learning to keep quiet and run my mouth.

In an emerging adult’s encounter with a sexually-abusive uncle, helplessness and anger embody his experience because his mother fails to stand up for him in spite of her knowledge of the abuse: “We ran into [my uncle] and he said to me, ‘you better shake my hand when you talk to me.’ My mom was standing there and didn’t do anything about it and so I was really upset.” As this case illustrates, a caregiver’s lack of response to abuse contributes to young persons developing incoherent images of selfworth and comfort and security in their social world.

Reactions to Stressful Experience

Following the onset or intensification of a family stressor, and the existing supports available to young persons, are their reactions to the stressful experience. Some young persons react to the stressor with shock and distress, even when they expected the stressor. When the source of stress is a family member, the stressor is formative because this family member now seems different, unrecognizable by others, and yet is part of daily life. An emerging adult describes her father’s erratic behavior after her mother asked him to leave the house because of his infidelity:

He was just really depressed, sad, crazy. He would like spy on my mom and have me help him and that was really hard. He couldn’t get in the house, so he would have me go open the house and that kind of thing. He was just crazy, unrecognizable.

Young persons react to the stressor with ambivalence, shame, and secrecy, and by reclaiming control. The first common reaction to a family stressor is ambivalence, with young persons experiencing relief and guilt when the family stressor is resolved. An emerging adult’s discourse reflects this, because the use of “kind of being like” in the following statement suggests guilt about the relief of his parents’ divorce:

I remember their divorce kind of being like a relief to my brothers and sisters and I; it was probably more stressful before they got divorced when they were just fighting all the time. And we all kind of knew that the divorce was coming.

This type of relief reaction is also common when young persons, typically during adolescence or in emerging adulthood, are able to reinterpret the stressor from an adult perspective:

I saw [the divorce] from an adult perspective, I saw that they weren’t in a healthy relationship and that it was for the best, whereas my younger sister, she just couldn’t understand why her dad wouldn’t be living there anymore.

A second common reaction to stressors among young persons is to focus on parts of life that are still within their control, such as relationships or projects, to bring about stability in their lives:

At least there was something that I could be good at and … I would study for as long as I wanted just to make sure that I could succeed in all of what I had control over. I felt like there are a lot of other events that I didn’t have control over.

In contrast, young persons who repeatedly experience low control over their lives, feel less able to persist in their projects. An emerging adult describes how being teased at school was exacerbated by her mother’s disparaging comments about her appearance. This formative experience shakes the person’s self-grounding and constrains the expression of her body.

A third common reaction is shame and secrecy about the stressful experience. Secrecy is more likely to take place with a stigmatizing stressor, such as a family member’s mental illness, sexual abuse, or sexual orientation, than with a more socially-accepted one, such as a family member with cancer or parents’ divorce. Secrecy allows young persons to project the illusion of normalcy and well-being, although it also keeps them from connecting and seeking support from others.

My family isn’t the type to acknowledge, you know, “Maybe you should go talk to someone about this.” I just kind of hid those feelings. My boyfriend said, “Why don’t you talk to your parents about [paying for your therapy],” and I said, “They’re just going to blow me off … and say, “You have nothing wrong.”

Reorganization and Burden

When the family stressor occurs, young persons’ appraisal of their and others’ reactions prompts them to take the action(s) necessary to manage the stressor and restore normalcy. This shift often leads to reorganization of the family.

Parentification

Emerging adults describe the perceived need to care for younger siblings or a parent in the physical or emotional absence of a parent. This desire to protect younger siblings or a parent is often driven by fear that the family will fall apart, such as when parents divorce:

It is hard because my dad will come to me and at one point he had lost his job and so I was buying him groceries and helping pay his rent…. Then for the holidays it is my responsibility to make sure that us three girls spend equal amounts of time with both sides of the family, so I feel like I am taking on the parenting role now.

A parentified role implies doing household chores, mediating conflict between family members, getting siblings ready for school, and being a confidant to or caring for an impaired parent. Emerging adults indicate a different way of relating to their parents during childhood, hence the formative nature of the experience, as in the following example:

My mom would have me come in [the bathroom] and I would be on the bathtub and she would sit on the toilet seat and she would be smoking away and she would tell me all of her problems and that was my mom time. You know, that was when I could actually talk to my mom and … I always felt like I acted like a counselor for all of those years.

Burden on sense of normality

Although emerging adults recall their desire to care for others while the family adapts to a stressful experience, parentification often burdens young persons’ self:

I got to learn how to cook at an early age because my mom stopped cooking, and I know our house was always messy because my parents had three kids and my dad was working and he couldn’t clean it up and I would try to clean up because I’m the oldest in the family. My brothers and sisters were like, “Oh, we don’t care if we make a mess” and my mom would never get up and clean … so I had to do it.

This emerging adult added how “being a parent” robbed her of a normal childhood, “It was embarrassing to see the house so messy so I never had friends come over. All I wanted was a normal childhood with friends coming to my house.” This theme of normality is formative because many emerging adults enter college with a damaged view of themselves.

Because parentification also heightens young persons’ sense of obligation to their younger siblings, it not only robs young persons of a normal childhood, it also forces emerging adults to sacrifice their interests for their siblings’ interests. An emerging adult describes a pull to protect her younger sister, at the expense of her dreams of pursuing graduate school:

My mom has recently become involved with someone who has a past of domestic violence and I told her, “If things become serious between you two and he moves into the house, I don’t want my sister there. I don’t want her to go through what I went through as a child.” I would fight for her custody, I don’t know how, but I would find the way.

Young persons’ interactions with the impaired person formatively shift their sense of what is normal. An emerging adult recalls “walking on eggshells” to avoid outbursts from her mentally ill sister. Another emerging adult’s embodiment of the experience could not allow herself to mourn her brother’s erratic behavior. Another recalls life with a mentally ill father:

Every day we would have to sit in the car while my mom went inside to see if [dad] had killed himself. That’s how bad it got. And it happened a lot, so it was always there and it was all very damaging. It never allowed me to have a normal childhood.

Lack of normality permeates this person’s sense of space and time: home is no longer a place of security and comfort and time stands still as it revolves around the father’s illness. The emerging adult’s descriptions of the situation as damaging also point to its formative impact on her emerging adult self, one that feels flawed. A duality of owning and disowning and approaching and distancing from the experience emerges, affecting the person over time.

Enduring Expressions of Burden

Ongoing stressors or persistent changes in family organization often affect young persons’ functioning into emerging adulthood. They experience changes in their academic, career, or social projects; relationships with others; and embodiment or activation and regulation of emotions, particularly when facing new demands in college.

Academic difficulties

Emerging adults note common academic difficulties including failing or struggling with classes, decreased focus and motivation, and believing they are “invisible” in a university setting. An emerging adult explains how family stress affected her college academics:

You go to sleep crying and wake up crying … I’d be crying in class; a lot of suicidal thoughts … and it’s almost like there’s something going on in my head that’s generally negative in nature…. Academically, I just couldn’t concentrate for the first two years of college. I’m in a scholarship program and any time you don’t live up to the program’s expectations, you have to see the Head of the program. I feel like I’m not even in college for myself anymore, I’m just doing it to uphold the expectations of that program.

Another emerging adult explains how her academics and relationships worsened as her sense of efficacy and self became weaker, “I always did bad in school, but I probably did worse [in college] because I didn’t feel confident. I was also more irritable myself and I was less confident in relationships, so I had fewer friends.” The experience of this emerging adult exemplifies how academics are linked to functioning in other areas, such as social relationships.

Interpersonal difficulties

Interpersonal difficulties are also common to the formative family stress experience. While some emerging adults experience healthy college relationships, others avoid intimacy out of fear of recapitulating unhealthy patterns. These emerging adults feel unresolved loss about their unhealthy and absent relationships with their mentally ill or abusive fathers:

(Emerging adult 1) I haven’t had the best judgment with men and I really struggle with trust. I never had that male relationship in my life…. It’s like some people have their fathers die and I feel the same way. I never had a dad. I lost my dad.

(Emerging adult 2) I think part of the reason that I don’t date often, or at all for that matter, is because I just don’t trust men after the things that I’ve seen with my mom and the way that my father and my older sister’s father didn’t stick around. I have a really hard time trusting a lot of people, and so quite a few of my friendships went downhill this past year…. Maybe I’m just afraid of being abandoned again; I think that’s kind of a theme that I see occurring in a lot of relationships is just feeling like I get abandoned.

In these situations, the emerging adult has no grounding or social base and therefore she is constrained in her current relationships by her formative familial experiences. Her sense of self is also shaky because she does not trust her own ability to establish healthy relationships.

Emotional difficulties

Finally, changes are seen in emerging adults’ ability to contain, activate, and regulate their bodies, particularly their emotions and behaviors. Emotional problems are new for some emerging adults as they enter college, but for others they are a continuation from earlier functioning. One emerging adult recalls how in college, “It all started spiraling around in my head. I got really depressed and I would do things like cut myself, throw up and exercise obsessively.” Controlling one’s body is a way of rescuing control over life. These bodily reactions are a cruel reminder of one’s past, one that cannot entirely be left behind.

For many emerging adults, these emotional difficulties were exacerbated by their loved ones’ inability to support them:

There were a few days [in college] when I didn’t want to get out of bed I felt so sad…. I wanted to think of the way to bring it up to my mom and so one night I got the courage to call my mom and I was almost crying and said, “Hey, I was wondering if you would give me the phone number to our doctor because I want to ask about the side effect of birth control pills because I really think that I’ve been suffering from depression and I just want to know if that is a side effect.” And she said, “Oh, I will give you the phone number tomorrow, I can’t really give it to you right now.” And I said, “Okay, thanks” and then she hung up the phone. And it makes me kind of more sad to think about her response, sorry (crying) … that was a time where she really just didn’t care.

Resilience

A few emerging adults experiencing a stressful family experience are able to function well emotionally, behaviorally, interpersonally, and academically. In spite of their family hardships, these adults rely on a supportive person and have high self-esteem. An emerging adult whose parents divorced explains why she did well academically throughout her life:

Well growing up when they were together they both always helped me with homework and I was really good at school. And then I still did well at school [after the divorce], but I did it all on my own. I think that actually helped me because I learned how to study.

In addition to having external supports, resilient emerging adults are also characterized internally by a sense of self-determination. The following emerging adult believed she could create change in her life through her long-term goals and endurance:

I think I’m the only one who can help myself…. Because even though it is important to have the outside support, it’s also important to have the character to be able to pull myself through it and continue to just push myself. I think that is really helpful to have a long-term goal, like grad school. That helps me to make a difference in everything.

Relief from Burden

Emerging adults seek relief from the burden of parentification and a resulting lack of normality through internal and external resources, as well as a focus on college and relationships.

Internal and external resources to achieve relief

Emerging adults pull from internal and external resources, varying from active, positive strategies to get through difficult times to passive, negative strategies to temporarily escape the pain in their lives.

Active and positive strategies mentioned by emerging adults include seeking therapy, reaching out to friends, focusing on academics, taking care of their nutrition and health, engaging in religious or spiritual practices, and participating in a variety of extracurricular activities. These activities provide a new sense of self and agency, and offer a distraction from family problems. An emerging adult talked about the role her therapist played in her healing process:

I remember being scared and then she just talked and didn’t make me talk all that much at first. And we did activities to see how I viewed my family…. And then she is also really big on yoga and meditation and focusing on being in your body. That was a big thing. Just getting out of what you are thinking in your head and instead feeling what you are feeling in your body. I think that really helped me to be more present in my body.

Passive or negative relief efforts include isolation from others, and becoming numb to the stressor (e.g., wishing problems away, substance abuse, excessive weight control). Although emerging adults recognize the deleterious effects of these efforts, these provide respite from their painful reality, which is deeply formed by their family problems. These adults also experience more control of nonsocial objects (e.g., substances and weight control) than social relationships.

Well, bulimia was a source of coping, I mean I still have a lot of issues with the way I look and stuff, but I think that it escalated back then, and I don’t know if I did it to harm myself, but I think it was just a way of not liking myself for stuff that happened.

College as a source of relief

Many emerging adults look for places of comfort and hope that going away to college will provide the distance they need to no longer deal with their home environment. As one emerging adult put it, “leaving home and going to college was the best medicine in the world.” Others view college as an opportunity to “have a normal life,” to compartmentalize their life in such a way that friends are often unaware of emerging adults’ “other life.” However, some emerging adults come to realize that they cannot fully escape their ties to their family. An emerging adult with divorcing parents describes this formative experience:

I thought I would finally live a normal life once I got to college. Then the calls started coming in, my mom and dad playing the “he said, she said” game, and my younger sister calling in tears because the problems at home were really getting to her. It hurt my grades because it was an added stress in my life. I was trying to work, trying to go to school, and then dealing with this at home, it was really stressful trying to focus on my studies.

There is no relief from the emotional burden of this emerging adult’s home environment. Instead, a cycle of obligations, resentment, and guilt follows as she is caught between two worlds. For others, college provides the distance they need, but comes with its own challenges:

I always just thought that if I can do really well in school I could leave and go somewhere else; no one will be able to bother me later on. But then when I got to college I was so distant from everyone and campus was so large … that I felt even more lonely … so my academics went way down from high school.

Social support as a source of relief

Many emerging adults rely on their interpersonal relationships to get through the difficult times at home. Emotional support and acceptance is mainly sought from family members, friends, and mental health professionals.

What’s helped me cope is a friend of mine out in LA. She also has depression and she’s probably the closest friend I’ve had. So when I have problems I can call her and talk to her about things and she generally knows what it’s like to go through them.

Some emerging adults seeking social support experience the cost of sharing too much about their family, particularly when others are burdened by the stressful reactions of emerging adults. Fear of burdening other relationships also reinforces isolation and secrecy.

Evolution and Redefinition of Family

As young persons manage the burden caused by a stressful experience, family relationships evolve in such a way that close family members become closer and distant family members become more distant. This is the case when family members bond and create a shared identity by excluding a “problem” family member. Although exclusion of this person allows emerging adults to redefine the family, and create positive formative experiences, this person continues to hold real or perceived power over the family, as in the following example:

In the last couple of years, I’ve cut off contact from my dad. The problem is he’s still living with my mom so things will never get better until my dad actually leaves our lives. I think that we can be a very close family. I think that me and my mom and my sister have been close and I feel closer to them now after all we’ve been through.

For some emerging adults, the formative experience is so strong that they are not able to separate their selfhood from their present relationships and experience a cycle of obligation, resentment, and guilt. An emerging adult whose father was in prison for homicide recalls being conflicted about her obligation to her disengaged father:

Well, I’ve been trying to … battling between acceptance of him or rejection of how he is, so … he’s 60 years old and not going to change; should I just love him for how he is and just be there for him because he needs somebody to be there for him? Or should I just act—”You screwed up so much I don’t want to see you, I don’t want to talk to you,” that kind of stuff…. I go back and forth, you know … cause [my father’s] birthday is in two days actually. So I’m like, you know, he hasn’t called me on any of my birthdays in the past however many years, should I be the one to reach out and try to call him more?

Another emerging adult describes the fear of closing the door on her conflicted relationship with her alcoholic father in spite of being vulnerable in that relationship.

I feel like I am more sympathetic towards him now or this is probably a bad word to say, but I almost pity him now to the point where I feel sorry for him that he is on his own now. He is still my dad and as bad of history as the two of us have, I still have to put those bad feelings aside and help him because obviously he is still struggling emotionally.

Integration and Healing

Time and an adult perspective allow many emerging adults to come to terms, redefine, or integrate their formative family stressful experience in efforts to reach resolution. Many emerging adults look back on the experience with acceptance, gratitude, and transcendence:

I think it wasn’t until I went to college until I really had a chance to be away and like I think about it and realize, “Oh my gosh, this is so bad, it was so bad.” But it’s made me grow up so much…. I think it’s actually benefited me, it sounds weird as hard as it was emotionally, I think that it was actually a really good thing because I got to experience something different than a lot of people did.

This emerging adult transcended the pain from her past by comparing her lived experience to that of others who have lived “sheltered” lives. Another emerging adult reflects on the new order in her life, one of strength through adversity and a renewed sense of agency:

I think that after months, you just feel empowered because you got through it. You know I’ve never been through anything that hard, and I was away from home on my own and just, to be able to wake up in the morning and know that I had survived and that I could go out into the world and do something, that really affected me in a positive way … in the relationships afterwards I have been, I know more about how I want it to be.

In this situation, there is a returning to selfhood. A new identity and sense of self relative to others develops over time as emerging adults begin to heal from the stressful experience. In addition, emerging adults see themselves as wounded healers who can now help others make it through stressful family experiences. This is their legacy of survivorship, an identity they’ve come to accept. For some emerging adults, the lived experience of family stress increases their empathy toward others facing family stressors. An emerging adult whose grandmother was diagnosed with schizophrenia recalls her increased empathy for those with mental illness:

As I got older I started to understand what it’s like to love someone with schizophrenia and it made me want to go into a psychology career. My sister is also a nurse now and so for us I think that it’s helped us in our careers. Especially for me, it’s just given me a lot of empathy for people who do have a mental illness as well as for their families.

For others, integration of the family experience stands on shaky ground because they are limited to the damaging parts of the experience. A few emerging adults view the experience as a scar that will never heal. An emerging adult talks about how the family stressor robbed her of “a normal life”; another talks about how she resents that her family problems have affected her interactions with others and reliance on others for trust and companionship.

Discussion

We aimed to elucidate the essential processes of formative family stress for emerging adults in the context of every day family life, and the implicit psychological meanings connected to those processes. In this section, we discuss our findings as they relate to the literature on emerging adulthood and family stress, and propose a model of family stress using phenomenology.

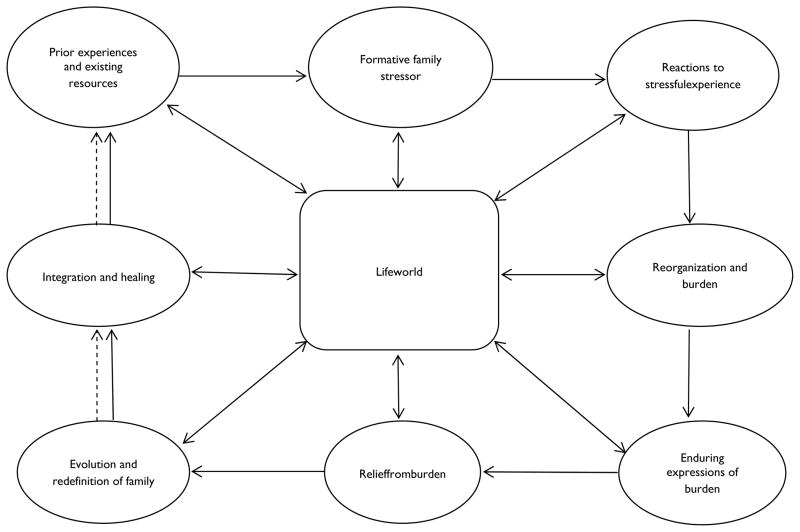

In terms of shifts and progressions in the experience of family stress (see Figure 1), emerging adults described family life prior to the onset or intensification of a formative family stressor, as a way to contextualize the shifts and progressions in family life and the family’s existing resources to manage the stressor. Emerging adults differed in their reactions to a family stressor, ranging from shock and devastation, to anticipation and relief. The family attempted to adapt by reorganizing, with children typically taking on adult responsibilities. Family life then became burdensome and robbed young persons of a “normal” life, altering their academic, emotional, and social functioning over time.

Figure 1.

Phenomenological model of family stress for emerging adults

Some emerging adults in our study sought relief from this burden, and their efforts included seeking therapy and social support and focusing on parts of life that were under their control. Conversely, a few emerging adults engaged in risky behavior in an attempt to split desirable from undesirable views of themselves. Over time some family relationships became closer and others became more distant. Some emerging adults resolved their lived experience with resilience and endurance, whereas others felt permanently damaged by the experience. For the majority of participants, these processes began in childhood, but continued into emerging adulthood. These processes were dynamic and interdependent, and had a cumulative effect on future defining events in the lives of emerging adults. The essence of this lived experience has been reported in other studies involving stress (Fischer & Wertz, 2002) and is consistent with recent literature documenting the enduring effects of the family in emerging adulthood (Aquilino, 2006; Friedlander et al., 2007; Masten & Shaffer, 2006).

The shifts and progressions in the experience of family stress described above were interdependent with emerging adults’ lifeworld, that is the implicit, taken-for-granted psychological meanings of their experience. These meanings became explicit phenomenologically through emerging adults’ detailed personal accounts of family life. A primary meaning identified was that of an evolving selfhood and identity that were continually threatened. These young persons vacillated between owning and disowning and approaching and distancing from their perceived “flawed” family that was reflective of a flawed self.

Emerging adults also perceived their lived world as a burden to others in and out of the family. The selfhood could not be separated from sociality, leading to isolation and relationships with controllable, nonsocial objects. Self was also constrained and frustrated by obligations to the family. In addition, emerging adults experienced a sense of ungrounding, unpredictability, and mistrust in familial and personal relationships. Regarding family stress and embodiment, emerging adults sensed that their body was not their own when they were at home. Many parents discouraged emerging adults from seeking professional help, as this was seen as a sign of “weakness” in the family discourse. Emerging adults recalled reacting to family stress somatically, particularly through intense emotions and physiological reactions.

The relationship between family stress and temporality was also evident and was a sign of an “endurance” discourse. Many young persons waited for time to pass, as if there was no other option than to accept what was happening in the family, until they could find independence to act. Going to college afforded many emerging adults independence that allowed them to create spaces of comfort and security. However, the home environment was often inseparable from the college environment, as when family members depended on emerging adults from a distance.

In response to family stress, emerging adults’ project became a striving toward “normalcy.” College was seen in part as an opportunity to escape or separate the self from a constraining family culture. Moreover, because social comparison was prominent within this phase of life, emerging adults strived for a discourse of “normalcy.” Finally, on reflection of the life lived, several emerging adults felt empowered by their “endurance” or “survivorship.”

Many emerging adults reflected on their formative stressful experience with self-determination and growth, which have been previously linked with psychological well-being (McAdams et al., 2006). In fact, the ability of emerging adults to leave their home environment to pursue college illustrates the possession of internal and external adaptive resources protecting them from early adversity (Luecken & Gress, 2010). Emerging adults with limited resources commonly have few supportive adults in the family (Masten & Shaffer, 2006).

The role of a supportive, healthy adult figure in enhancing emerging adults’ resilience highlights the value of family prevention programs and interventions, in which all family members are targets and facilitators of change (Valdez et al., 2011). These interventions hold promise in fostering a shared understanding of the family and in strengthening cohesion and support among family members. Ultimately, the presence of supportive family members enhances children’s developing lifeworld and their ability to individuate over time. This support allows the young adult to aptly face the demands of college life. Interventions that also increase social support from peers and trustworthy adults outside the family also need to be developed as emerging adults transition from the home environment to college (Friedlander et al., 2007).

Our model was consistent with the Double ABC-X (McCubbin & Patterson, 2002) in that family adaptation to a stressful experience rested on the foundation of having experienced and adapted to previous stressors. In response to increased stress or a new stressor, families pulled from their existing resources to manage stressful experiences, mainly through reorganizing family roles. The perception of the stressor had an impact on individuals’ functioning over time, and their eventual adaptation impacted not only how their family relationships evolved, but also their new baseline of resources and meanings.

Unlike the Double ABC-X model, that primarily describes adaptation at the family level, we used a phenomenological model that detailed the personally-intimate psychological meanings of young persons experiencing family stress. These subjective meanings were formative, in that they shaped how young persons met developmental tasks and formed enduring images of family life and relationships. In addition, the Double ABC-X model describes general factors influencing adaptation, such as coping resources and beliefs about stressor. In our model, psychological meanings allowed us to detail the specific beliefs and representations shaping emerging adults’ adaptation to the experience of family stress.

The existing literature has highlighted the need to account for family life in the study of adaptation. Fiese and Spagnola (2006) highlight the role of family routines and representations as stabilizing forces during times of stress. Our work, like theirs, informed how family life shapes individuals and how individuals’ representations of family life, in turn shapes adaptation to family life (Fiese & Spagnola, 2006). Our work focused on emerging adults, who have been largely understudied in the family literature. Another strength of our article was our focus on emerging adults’ representations of diverse family stressors.

Although details of daily family life were dependent on recollections of emerging adults, other researchers have demonstrated that the psychological meanings about the self and the world are likely to be consistent over time because of the emotion connected to the experience (McAdams et al., 2006). Contextualizing these adults’ struggles and meanings can guide the therapeutic work of professionals working with emerging adults. Through a deep empathic process, health care professionals can help emerging adults integrate opposing views of the self.

Career counselors and professors can also explore stressful family experiences during their encounters with emerging adults. Exploring family life during student encounters would optimize the referral of emerging adults to specialized psychological and psychiatric services as well as to family support programs. The role of non-clinical professionals in this identification is important given that many emerging adults do not seek counseling (Dyson & Renk, 2006).

Although many emerging adults in this article showed great resilience, in general, family stress had deleterious effects on adaptation over time, which has been found by other researchers (Masten & Shaffer, 2006). Participants in the current article often had lower academic, interpersonal, or emotional functioning as they faced new demands in the college environment. Because of the large number of college students presenting with these difficulties (Dyson & Renk, 2006), psychological interventions with emerging adults need to be developed and should promote engagement in academic, social, and health-related activities that allow emerging adults to reclaim control of their lives. These interventions would be ideally available in college health centers and counseling centers, as well as through various student groups.

Limitations

The majority of participants were older, White women. Whether the lived experience differs for men, younger adults, or for other ethnic/racial groups would be helpful in tailoring services and interventions for those populations. We also focused on emerging adults who are in college; future studies should examine family stress for emerging adults not attending college and examine features of the lived experience that are unique to these young adults.

Although emerging adults’ essential lived experience of family stress was revealed, a deeper exploration might unveil unique characteristics of the experience that differ from those of other emerging adults (Worthen & McNeill, 1996). We aimed to provide a window into the lived family experience of emerging adults that often goes unacknowledged in research and undetected in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alberta Gloria for auditing our coding and Steve Quintana for reading earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and or publication of this article: Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Funding for this project was also provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Biographies

Carmen R. Valdez, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Tom Chavez, MA, is a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Julie Woulfe, MS, is a doctoral student at Boston College in Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aquilino W. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood; pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth P. An approach to phenomenological psychology: The contingencies of the lifeworld. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 2003;34:145–156. doi: 10.1163/156916203322847119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boss P. Family stress: Classic and contemporary readings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson R, Renk K. Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1231–1244. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20295. doi:10.1002.jclp.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Spagnola M. The interior life of the family: Looking from the inside out and the outside in. In: Masten A, editor. Multilevel dynamics in developmental psychopathology: Pathways to the future. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CT, Wertz FJ. Empirical phenomenological analysis of being criminally victimized. In: Hubberman AM, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion. London: Sage Publications; 2002. pp. 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander LJ, Reid GJ, Shupak N, Cribbie R. Social support, self-esteem, and stress as predictors of adjustment to university among first-year undergraduates. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48:259–274. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007/0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A, Giorgi B. Phenomenology. In: Smith JA, editor. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hubberman AM, Miles MB. The qualitative researcher’s companion. London: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Iverson-Gilbert J. Demand, support, and perception in family-related stress among Protestant clergy. Family Relations. 2003;52:249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00249.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Gress JL. Early adversity and resilience in emerging adulthood. In: Reich JW, Zautra A, Hall JS, editors. Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 238–237. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Shaffer A. How families matter in child development: Reflections from research on risk and resilience. In: Clarke-Steward A, Dunn J, editors. Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Bauer JJ, Sakaeda AR, Anyidoho NA, Machado MA, Magrino-Failla K, Pals JL. Continuity and change in the life story: A longitudinal study of autobiographical memories in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1371–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. Family adaption to crisis. In: McCubbin HI, Cauble AE, Patterson JM, editors. Family stress, coping, and social support. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas; 1982. pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- McLean KC, Breen AV, Fournier MA. Constructing the self in early, middle, and late adolescent boys: Narrative identity, individuation, and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:166–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00633.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman J, Bowen GL. Adolescents on the move: Adjustment to family relocation. Youth & Society. 1994;26:69–91. doi: 10.1177/0044118X94026001004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price SJ, Price CA, McKenry PC. Families and change: Coping with stressful events and transitions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ. Pathways to adulthood: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:667–692. 0360-0572/00/0815-0667$14.00. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez CR, Mills C, Barrueco S, Leis J, Riley A. A pilot study of a family-focused intervention for children and families affected by maternal depression. Journal of Family Therapy. 2011;33:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz FJ. Phenomenological research methods for counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:167–177. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen V, McNeill BW. A phenomenological investigation of “good” supervision events. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43:25–34. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.43.1.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]