Abstract

Carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide are important components of the carbon cycle. Major research efforts are underway to develop better technologies to utilize the abundant greenhouse gas, CO2, for harnessing ‘green’ energy and producing biofuels. One strategy is to convert CO2 into CO, which has been valued for many years as a synthetic feedstock for major industrial processes. Living organisms are masters of CO2 and CO chemistry and, here, we review the elegant ways that metalloenzymes catalyze reactions involving these simple compounds. After describing the chemical and physical properties of CO and CO2, we shift focus to the enzymes and the metal clusters in their active sites that catalyze transformations of these two molecules. We cover how the metal centers on CO dehydrogenase catalyze the interconversion of CO and CO2 and how pyruvate oxidoreductase, which contains thiamin pyrophosphate and multiple Fe4S4 clusters, catalyzes the addition and elimination of CO2 during intermediary metabolism. We also describe how the nickel center at the active site of acetyl-CoA synthase utilizes CO to generate the central metabolite, acetyl-CoA, as part of the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, and how CO is channelled from the CO dehydrogenase to the acetyl-CoA synthase active site. We cover how the corrinoid iron–sulfur protein interacts with acetyl-CoA synthase. This protein uses vitamin B12 and a Fe4S4 cluster to catalyze a key methyltransferase reaction involving an organometallic methyl-Co3+ intermediate. Studies of CO and CO2 enzymology are of practical significance, and offer fundamental insights into important biochemical reactions involving metallocenters that act as nucleophiles to form organometallic intermediates and catalyze C–C and C–S bond formations.

(I) Introduction

Every year, about 750 gigatonnes of relatively inert CO2 undergoes catalytic reactions that convert it into various forms of organic carbon that is combusted by living organisms and converted back to CO2 through the many reactions of the carbon cycle.1 Of the 2.6 gigatonnes of carbon monoxide released into the atmosphere every year, most reacts with hydroxyl radical in the trophosphere, while about 10% is removed by microbes,2,3 which have the ability to interconvert CO and CO2 through the activity of CO dehydrogenase. This review will focus on the metalloenzymes and on the catalytic metal centers that are involved in the microbial metabolism of CO and CO2.

There are six known cycles of microbial carbon dioxide fixation,4,5 which are summarized in Table 1. The Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle is used by plants and algae in addition to cyanobacteria and other eubacterial clades. The enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) in this cycle fixes CO2 into ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate. The other five pathways described are oxygen-sensitive. Three autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways have recently been discovered in archaea and bacteria by Georg Fuchs and his coworkers. The hydroxypropionate/malyl-CoA and hydroxypropionate/hydroxy-butyrate cycles include the same two CO2-fixing enzymes: propionyl-CoA carboxylase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase, while the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle includes pyruvate synthase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase to incorporate CO2 into organic carbon. The reductive citric acid cycle involves three CO2 fixing enzymes, which are also central to the oxidative citric acid (Krebs) cycle. The Wood-Ljungdahl or reductive acetyl-CoA pathway is unusual in that it generates CO as an intermediate and uses complex metal clusters and organometallic intermediates to fix CO and CO2 into cellular carbon. Because of the focus of this journal on metals, the enzymes of Wood-Ljungdahl pathway and their metallocenter active sites will be the main subjects of this review. This pathway enables strictly anaerobic bacteria to grow autotrophically on CO or CO2.

Table 1.

Known pathways of CO2 fixation by microbes

| Pathway name | CO2-fixing enzymes | Examples of Microbes | O2 sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calvin-Benson-Bassham Cycle | RubisCO | Aerobic autotrophic bacteria (cyanobacteria, purple sulfur bacteria… etc.) | Tolerant |

| Reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle | 2-oxoglutarate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, pyruvate synthase, PEP carboxylase | Bacteria such as Chlorobium sp. and Desulfobacter sp. | Sensitive |

| Reductive acetyl-CoA pathway | Acetyl-CoA synthase, formate dehydrogenase | Methanogenic archaea and acetogenic bacteria | Sensitive |

| 3-Hydroxypropionate/malyl-CoA cycle | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Propionyl-CoA carboxylase | Phototrophic bacterium, Chloroflexus aurantiacus | Sensitive |

| 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Propionyl-CoA carboxylase | Autotrophic Crenarchaeota, Sulfolobales, Metallospharea sedula | Microaerobic conditions |

| Dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle | Pyruvate synthase, Phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylase | Archaea such as Ignicoccus hospitalis, Thermoproteus neutrophilus | Sensitive |

This review will open with a broad description of the chemical and physical properties of CO and CO2 and of the different enzymatic reactions that utilize them. Then, the focus will turn to the enzymes and the metal clusters in their active sites that catalyze transformations of these two molecules. Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR), which contains thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) and multiple Fe4S4 clusters, is an example of a class of enzymes that catalyze carboxyl group additions and eliminations during intermediary metabolism in all kingdoms of life. The two types of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), which can contain a molybdopterin/copper (Mo-Cu-CODH) or nickel–iron–sulfur (Ni-CODH) active site, have the remarkable property of interconverting CO and CO2. Acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS), which forms a complex with the Ni-CODH, uses a nickel iron–sulfur cluster to catalyze the reaction of CO with two other substrates to generate the central metabolite acetyl-CoA. A CO channel between the CODH and ACS active sites ensures that CO does not escape from the protein during the enzymatic reaction. Linked to ACS is a corrinoid iron–sulfur protein (CFeSP) that uses vitamin B12 and a Fe4S4 cluster to catalyze a key methyl-transferase reaction involving an organometallic methyl-Co3+ intermediate.6

(II) Chemical, physical and biological properties of CO and CO2

(A) Physical properties of CO and CO2

Both CO and CO2 are colorless gases, and CO is odorless, whereas CO2 has a slightly pungent smell.7,8 CO is toxic to many organisms, and high levels of CO2 can become toxic in sealed environments. CO shares many properties with H2, including low solubility, strong reducing potential and high flammability.9 The solubilities of CO and CO2, which depend on temperature and partial pressure, are 22.66 ml kg−1 (1 mM) and 835 ml kg−1 (37.3 mM), respectively, at 20 °C and 1 atm.7,9 In aqueous solution, CO2 is in equilibrium with CO32− (carbonate) and HCO3− (bicarbonate), which are even more soluble than CO2 itself.7 Both gases have many industrial uses (especially CO2 in all of its forms), and they are released to the atmosphere from many industrial applications that lead to the complete and incomplete oxidation of hydrocarbons.8,9 Although the anthropogenic sources of CO and CO2 are often emphasized, the contributions of natural sources are significantly larger.7,9

(B) Common chemical reactions and industrial uses of CO and CO

As the most oxidized form of carbon, CO2 is produced by the complete oxidation of organic carbon. CO2 is inert under normal conditions; however, it becomes more reactive at high temperatures and in the presence of metal catalysts. Gaseous, solid and liquid carbon dioxide have many industrial uses ranging from being used as a chemical feedstock, a refrigerant as dry ice and as a stimulator of plant growth in greenhouses.7 CO2 can react with H2 to form CO and H2O, which is the reverse of the water–gas shift reaction. Another important industrial reaction is the Bosch-Meiser process, which involves the reaction of CO2 with NH3 to form urea, which has many industrial uses. Much of the industrially produced CO2 is a by-product of H2 production from CH4 related to the steam refining of natural gas or syngas.

Carbon monoxide is two electrons more reduced than CO2 and is formed during the incomplete combustion of any organic material. Because it is a strong electron donor, it is used as a reducing agent in some reactions with metals. One common industrial synthesis of CO is the steam reforming of natural gas. At high pressures, it forms carbonyl complexes with metals, and is commonly used in well-known synthetic processes to synthesize other chemicals such as formate, acetic acid and methanol. For example, the Monsanto process involves the synthesis of acetic acid from CO and methanol.8,9

(C) CO in biology and medical uses

Even though the toxicity of CO has long been known, its function as a signaling molecule and as a potential therapeutic agent is increasingly recognized.10 In humans, CO is produced from the degradation of heme by heme oxygenase and it is now known to be a signaling molecule in pathways involving guanylate cyclase and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK). The interaction with soluble guanylate cyclase has implicated a role for CO in vascular and smooth muscle relaxation. The anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of CO, protective effects of exogenously applied CO during stress, and possible therapeutic uses of CO in organ transplantation, vascular disease, and cancer are current research areas.10

(III) CO and CO2 in the environment

(A) CO and CO2 levels over earth’s history

CO2 is a greenhouse gas whose atmospheric concentration has increased by 36% since the beginning of the industrial revolution, and is at a current level of ~380 ppm. CO levels over earth’s history appear to track the frequency of volcanic emissions tempered by atmospheric chemistry, dropping from ~100 ppm in the early atmosphere to a current level of 35 to 130 ppb, with its highest levels in the Northern Hemisphere.11 While the lifetime of CO2 is~250 years, that of CO is only a few months due to its reaction with other chemicals, mainly hydroxyl radical in the troposphere.12,13

(B) Sources and sinks of CO and CO2

There are both natural and anthropogenic sources of CO2 and CO. These sources include oxidation of methane and other hydrocarbons in the atmosphere, natural decarboxylation and decarbonylation (tetrapyrrole degradation) reactions and fossil fuel usage for generating energy for electricity, transportation and other industrial activities, which all contribute ~12 billion tons of carbon/year to the atmosphere.3

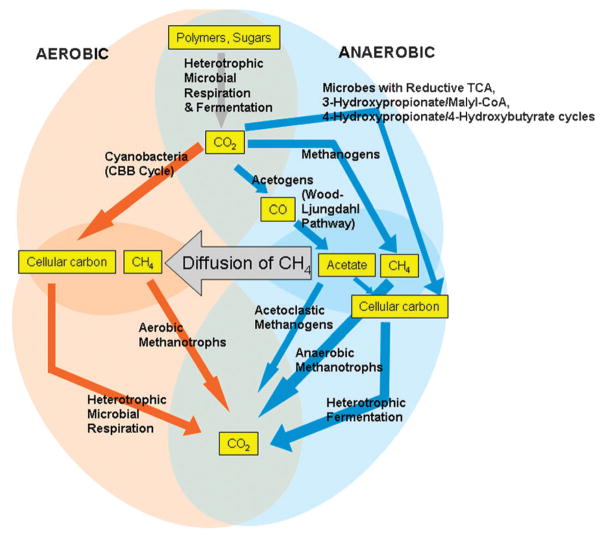

The natural sinks for CO2 are organisms that perform CO2 fixation. Plants are a good sink for CO2 since they use it for generating their cell carbon and are able to uptake more CO2 than they produce. Many different species of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and archaea also utilize CO2 or CO as electron acceptors and donors, respectively, and as carbon sources. Microbes in the soil and in the oceans produce and consume CO2 and CO, and hence play a central role in the carbon cycle. The soil and the oceans respectively absorb ~120 and ~90 billion tons of carbon annually.14 These fluxes take place with background carbon amounts of 2000 billion tons on land, 38 000 billion tons in the oceans and 730 billion tons in the atmosphere. The roles of the different types of microbes in the utilization of CO2 and CO are summarized in Fig. 1. The anaerobic marine sediments and plants in swamps and peatlands soak up CO2 to form our oil, coal, natural gas and fossil fuel reserves. There are six known CO2 fixing pathways.1,5 Plants, cyanobacteria and a variety of other microbes fix CO2 into cellular mass using the enzyme, ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RubisCO) in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle (a.k.a Calvin cycle). In addition to photosynthetic bacteria and cyanobacteria, some chemo-lithotrophs and methylotrophs use CO2 for making cellular biomass using the Calvin cycle. Phosphoribulokinase, which catalyzes the step before RubisCO, is another crucial enzyme in the Calvin cycle. The Calvin cycle is the only known aerobic carbon fixing pathway, all the other pathways being either somewhat sensitive to O2 or requiring strictly anaerobic conditions. The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is extremely oxygen-sensitive and relies heavily on complicated metalloclusters that are inactived upon exposure to O2.

Fig. 1.

Microorganisms that contribute to the carbon cycle.

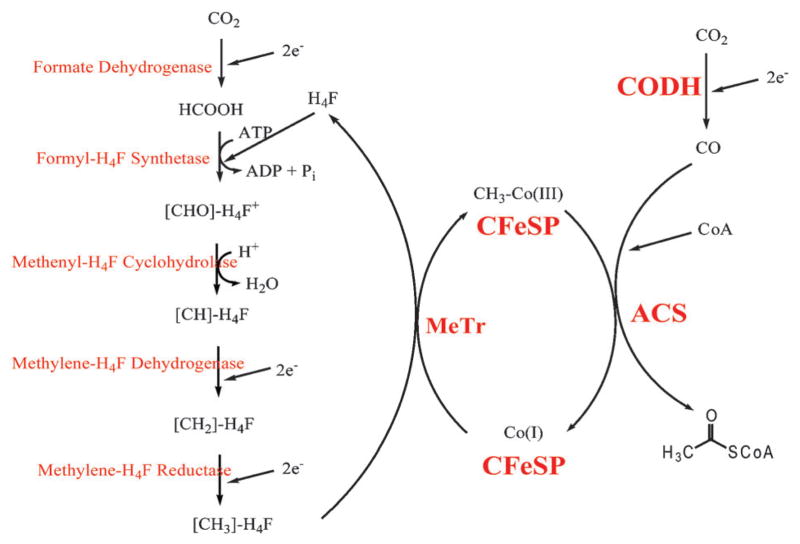

The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway15–17 (Fig. 2) is proposed to have fueled the emergence of life on earth.18,19 This pathway is used by anaerobic microbes in a wide range of phyla (acetogens, sulfate reducers, methanogenc archaea) for acetate oxidation or to convert CO or CO2 plus H2 into acetyl-CoA, which is used for ATP and cell carbon synthesis. Acetogenic bacteria also couple this metabolic sequence to other pathways like glycolysis to capture reducing equivalents generated during substrate oxidation for the reduction of CO2 (or CO) to acetyl-CoA. The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, as shown in Fig. 2, contains a methyl (left side) and a carbonyl (right side) branch. The methyl branch involves the six-electron reduction of CO2 to CH3–H4folate, by the folate-dependent one-carbon pathway present in all organisms. The carbonyl branch is unique to microbes using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway and involves the conversion of CH3–H4folate, CO2 and CoA into acetyl-CoA. The carbonyl branch exhibits distinctive mechanistic features, e.g., low-valent metallocenters serving as nucleophiles, enzymebound organometallic intermediates, unique active site metalloclusters, substrate-derived radicals, and channeling of gaseous substrates.

Fig. 2.

The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. On the left hand side, the Methyl branch is depicted where 1 mol of CO2 is reduced to methyl-tetrahydrofolate. On the right is the Carbonyl branch where acetyl-CoA is synthesized.

Atmospheric chemistry and uptake by soil bacteria are the major sinks for CO in the atmosphere. Aerobic carboxidotrophic (oxidizing CO at concentrations >1%) and carboxydovoric (using CO at concentrations<1000 ppm) bacteria and anaerobic microbes like acetogens and methanogens are the major CO oxidizers. Typically, the Mo-dependent carboxidobacterial enzymes have high CO affinities and low turnover numbers, while the anaerobic Ni-CODHs have slightly lower affinities and high turnover numbers, giving catalytic efficiencies of up to 109 M−1 s−1.20 Oxidation of natural hydrocarbons and CH4, and other energy-related emissions, such as incomplete combustion in automobile engines contribute to the net accumulation of CO in the atmosphere, especially in urban areas.

(IV) Non-enzymatic, inorganic compounds that catalyze reactions involving CO and CO2

Many types of inorganic compounds can catalyze reactions involving CO and CO2. CO is relatively reactive and can ligate to the low valent states of metal centers. There has been great interest in developing catalysts that can reduce the abundant greenhouse gas CO2 to other products, including methanol and CO.21 CO is especially valuable because it is used as a synthetic feedstock in some major industrial processes including the Fisher-Tropsch and Monsanto or Cativa processes for conversion of CO into liquid fuels and acetate, respectively. The major difficulty with CO2 reduction is that most catalysts that rely on one-electron reduction as an intermediate step must overcome highly unfavorable conversion of CO2 to the anion radical (CO2•−), which has a standard reduction potential (vs. SHE at pH 7) of −1.9 V vs. SHE.22 Some of the nonenzymatic catalysts are mimics of the natural reactions, such as the one catalyzed by CODH.23,24 However, the enzymatic catalyst, CODH, catalyzes CO2 reduction at the thermodynamic potential (which is −0.52 V vs SHE), i.e., without an overpotential. The proposed mechanism for CODH, which catalyzes reaction (1), is viewed to be similar to that of the water gas shift reaction (eqn (2)). Similarly, the reaction steps in the synthesis of acetyl-CoA by ACS are similar to those used by the Ru or Ir catalyst during acetate synthesis by the Monsanto and Cativa processes.

| (1) |

| (2) |

(A) Synthetic analogues of the aerobic Mo-Cu-CODH active site

Mo-Cu-CODHs are found in aerobic bacteria such as Oligotropha carboxidovorans and catalyze reaction (1), which has a standard reduction potential (for the reduction of CO2 to CO) of −0.520 V. The cofactor consists of a molybdenum ion bound to a pterin dithiolene, with additional hydroxide and oxo ligands, and a sulfur bridge to a Cu atom (Fig. 3). In a recent report, mimics of this active site were synthesized by reacting thiomolybdates such as [MoO2S2]2− with Cu complexes. The synthesized molecules were characterized by UV-VIS spectroscopy and crystallography, and some of them were found to be good structural analogs of the active site of the enzyme.25 Density functional theory (DFT) calculations on the model compounds representing possible reaction intermediates in the reaction cycle indicate that the bis-oxo form of Mo is the active catalyst.26 These computations also suggest that an n-butyl-isonitrile-bound structure of the active site observed in the crystal27 may not represent a structure that is analogous to what would be observed with the substrate, CO, because of the relative instability of this structure when CO is used in the calculations.26

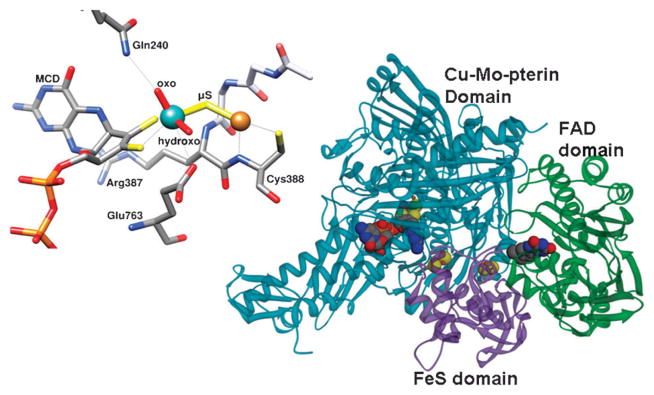

Fig. 3.

The structure of a heterotrimer of aerobic CODH and the active site of the aerobic CODH from Oligotropha carboxydovorans (pdb: 1N5W). The molybdenum atom is shown in cyan, the copper atom in orange. Contacts to both metals within 3.2 Å are shown as light grey lines. For Mo, these include the side chains of Gln 763 (3.16Å) and the sulfur atoms of the MCD cofactor (2.45Å and 2.49Å). For Cu, these include the backbone N (3.14 Å) and sulfur (2.22 Å) of Cys388. The cytosine portion of the MCD cofactor is not shown. The overall structure of a monomer on the right shows the Cu-Mo-pterin domain in blue, the Fe2S2 domain in pink, and the FAD domain in green.

(B) Synthetic analogues of the anaerobic Ni-CODH active site

The anaerobic CODHs also catalyze reaction (1). Model complexes have been synthesized that can catalyze either CO oxidation or its reverse. Some of these were synthesized before the active site structure was known by X-ray crystallography, while many of those synthesized afterwards focus on mimicking the NiFe3S4 fragment and the pendant Fe atom (Fig. 4c).24 Complexes containing Ni(II) cyclam Cl2 that can catalyze CO2 reduction to CO require very negative redox potentials (~−1.0 V).28 Tetraazamacrocyclic complexes of Ni and Co can catalyze this reaction along with the reduction of protons to H2, 29 and there are several reports of CO2 reduction by porphyrins or phthalocyanine with Co and Fe bound.30–32 A carbene-supported copper boryl complex and other copper complexes also reduce CO2 and some Cu complexes even reduce CO2 to methane and ethane.33,34 Even less complicated inorganic compounds such as TiO2 and ZrO2 can catalyze the reduction of CO2 when excited with certain energies of light.35 Monometallic and bimetallic Pd complexes exhibit high catalytic rates (up to 104 M−1 s−1) and low overpotentials (0.1 to 0.3 V) for CO2 reduction, yet they exhibit only 10–100 catalytic turnovers before the catalyst undergoes deactivation.36 More recently, a complicated Rhenium complex was used to reduce CO2 to CO with H2 as the electron donor.37

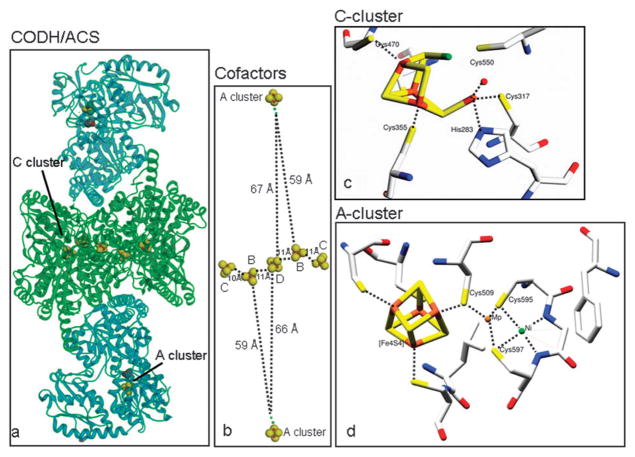

Fig. 4.

Overall structure of the bifunctional CODH/ACS from Moorella thermoacetica (pdb:1MJG) is shown in (a). The distances between the cofactors, Clusters B, C and D are close enough for electron transfer to happen inside the CODH subunit, but not to the A cluster, which is 59–67 Å away (b). In panel c, depicting the active site of CODH II from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans, from (pdb:1JJY), the nickel atom is shown in green, iron atoms in brown, and sulfur atoms in yellow. All residues coordinating the metal cluster are shown. In lower right panel d, where active site of ACS from Moorella thermoacetica (pdb:1MJG) is depicted, the Fe4S4 cluster, the proximal and distal metals, and the cysteine ligands are shown. In this crystal structure, the proximal position was occupied with Cu instead of the native Ni residue.44 Zn can also be found in the Mp site.

Some Ni(II) complexes with O-, N- and S-donor ligands can catalyze CO oxidation with methyl viologen as electron acceptor at very low catalytic rates such as ~0.00027 turnovers/s.38 CO oxidation on Cu oxide related catalysts is another well-studied system due to practical applications such as automative exhaust control, and some systems in cetain conditions are able to convert 90% of CO within minutes.39,40 Some other research has looked at the transformation of CO further to formyl, hydroxymethyl and methyl groups on metal rhenium complexes.21

Biomimetic model complexes related to CODH composed of cubane-type and cubanoid NiFe3S4 clusters have been synthesized and characterized by crystallography, redox potentiometry and Mössbauer spectroscopy, but the CO/CO2 conversion activities of these complexes have not been tested. A cubanoid structure, [(tdt)NiFe3S4(LS3)]3− (where LS3: a semirigid trithiolate ligand, tdt: toluene-3,4-dithiolate), mimicked the important aspects of the C-cluster, such as the square planar, four-coordinate Ni2+ at one corner of the cubanoid, however it lacked the exo Fe found in the CODH active site.41 This work was an extension of earlier studies on the synthesis of cubanoid type clusters with [NiFe3S4]+ cores with a planar Ni geometry where it was possible to insert other metals such as Pd2+ and Pt2+ in place of Ni2+.42 There have been some recent syntheses of complexes that mimic exclusively the Ni2+-Exo-Fe2+ component of the C-cluster.43

(C) Inorganic model compounds similar to the A-cluster

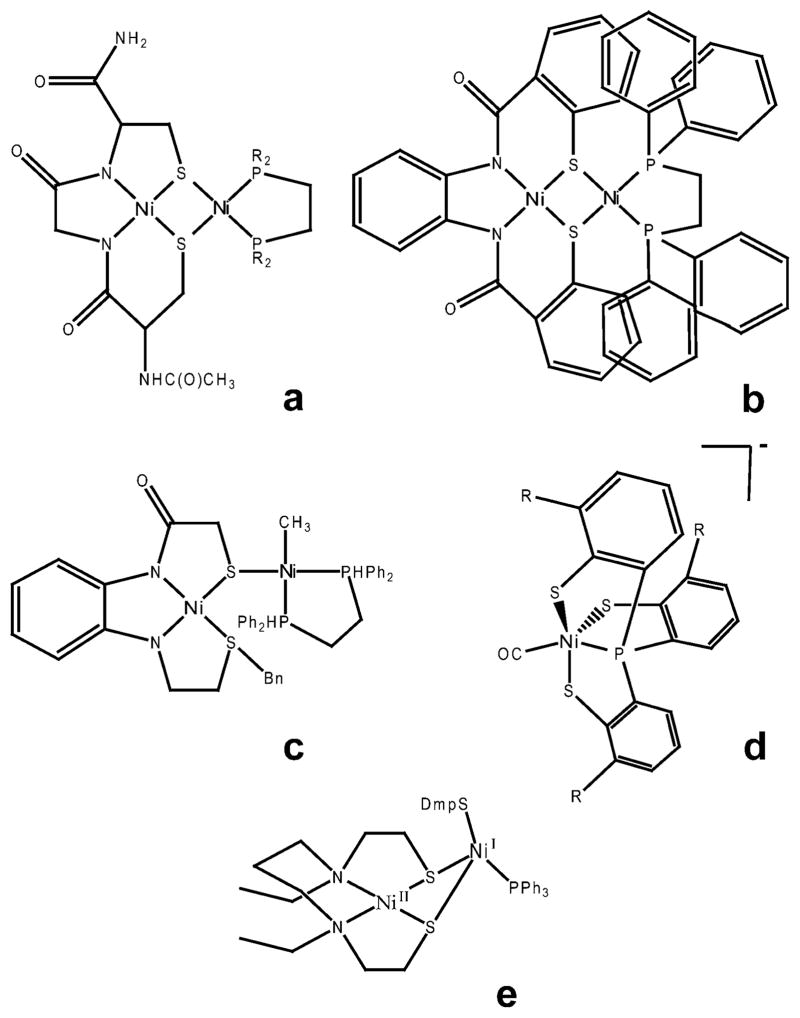

Since the discovery of the A-cluster (Fig. 4d), there have been many attempts to synthesize model compounds with similar properties to, or that mimic the different parts of the A-cluster. The review by Riordan gives a succinct survey of the earlier model compounds that were synthesized and analyzed.45 There have been other excellent reviews of early models of the A-cluster.24,46 Thioether ligands provide good models in providing electron densities on Ni similar to the one in the protein. A Cys-Gly-Cys peptide has also been used to generate the square planar Ni2+ complex, and binuclear derivatives of this complex, such as [(CysGlyCys)Ni]Ni(dppe) (Fig. 5a) have also been synthesized. In these binuclear complexes, the Ni that is equivalent to the Nip of the enzyme could undergo two-electron reduction to Ni0.

Fig. 5.

Examples of inorganic A-cluster mimics from the literature with similar properties to the A-cluster. a: [(CysGlyCys)Ni]Ni(dppe),47 b: [NiII(dppe)NiII(PhPepS)],48 c: Methyl-Ni complex,49 d: [PPN][NiIII(R)-(P(C6H3-3-SiMe3-2-S)3)]−,50 e: NiII(dadtEt)NiI(SDmp)-(PPh3).51

Some single Ni(II) compounds with one amine and three thioester donors to Ni, are able to be methylated, react with CO to form acetyl groups, and acetylate thiol substrates.46 Similarly, early model studies of the Nid site revealed some key features such as the square-planar Ni(II) geometry and the very low potentials required for CO2 reduction. Bi or trinuclear sulfur-bridged Ni complexes have been synthesized and their reduction and reaction with CO were studied. The compound, [NiII(dppe)NiII(PhPepS)] (Fig. 5b) showed striking similarity in EPR and IR spectra to ACS when CO was bound in reducing conditions.46

Harrop et al. synthesized a dinuclear nickel center model (Fig. 5b) with a dicarboxamido–dithiolate ligated Nid mimic sulfur-bridged to a Ni(II) center that could be reduced to Ni(I) and bind CO to form a putative six coordinate Ni(I)–CO complex. The IR spectrum of this complex is similar to the Ni(I)–CO band observed with ACS.48 Riordan’s lab also synthesized a dinuclear Ni(II) complex from a Cys-Gly-Cys bound Nid site and (R2PCH2CH2PR2)–NiCl2 (Fig. 5a).47 More recently, single thiolato-bridged binuclear Ni–S–Ni complexes were formed by reacting Ni(N2S2) compounds with (dppe)Ni(CH3)Cl, which provided analogues for the methylated A-cluster (Fig. 5c).49 These compounds had labile Ni–S bonds and are prone to dissociation/religation. An EPR-active Ni(III)-alkyl intermediate was observed and characterized in a distorted trigonal bipyramidal environment, with a model compound mimicking only the Nip portion of the A-cluster (Fig. 5d),50 giving support to the proposed mechanism with high valent Ni(III)–CH3 or Ni(III)-acetyl intermediates. The Tatsumi lab synthesized analogues of the A-cluster, one of which is shown in Fig. 5e, that can be methylated by methyl-cobaloxime, and that can further react with CO to form an acetylthioester compound similar to acetyl-CoA.51,52 In these studies, the compound Ni(dadtEt)Ni(Me)(SDmp), where dadtEt stands for N,N′-diethyl-3,7-diazanonane-1,9-dithiolate and Dmp for 2,6-dimesitylphenyl, was synthesized as a NiII–NiI complex. It had a S = 1/2 EPR signal (gx,y,z = 2.62, 2.12, 2.00), could be methylated and then react with CO. In the previous study, a similar complex was synthesized that had oxidation states of NiII–Ni0, but reacted with CO aftermethylation at a rate that is ~37 times lower than the NiII–NiI compound. Other studies in the Hegg lab with model compounds of Nid indicate that Nid may be directly involved in the chemistry because the bisamidate ligation causes the NiIII/NiII redox potential to be much lower than previously thought.53 This finding raises the possibility that Nid(III) is a viable intermediate andNid could be considered for a role in the internal redox chemistry in the ACS mechanism.

(V) Enzymatic reactions involving CO and CO2

Table 2 summarizes the major reactions that involve CO or CO2 as substrate or product. The carboxylation and decarboxylation mechanisms are described in greater detail in Frey and Hegeman, 2007.54

Table 2.

Reactions involving CO and CO2 as either substrate or product

| Reaction type | Cofactor | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Decarboxylation | TPP55,56 | Phenylpyruvate decarboxylase, pyruvate decarboxylase, pyruvate oxidase, 2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase. |

| PLP78 | Amino acid decarboxylase, ornithine decarboxylase, dialkylglycine decarboxylase. | |

| Cofactor independent79 | Acetoacetate decarboxylase. | |

| Protein-radical80 | Pyruvate formate lyase. | |

| Carboxylation | Biotin81,82 | Acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA carboxylases, pyruvate carboxylase. |

| Metals82,83 | Acetone carboxylase, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate decarboxylase (RubisCO), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, pyruvate synthase, pyruvate carboxylase, acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA carboxylases. | |

| Acetyl-Coenzyme A (strong activator)84 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. | |

| Decarbonylation | Various cofactors85 | Formation of CO for H-cluster,57 heme oxygenase, 3-hydroxy-4-oxoquinoline-2,4-dioxygenase, quercetin-2,3-dioxygenase, octadecanal decarbonylase, acireductone dioxygenase, acetyl-CoA decarbonylase synthase |

| CO as substrate | C-cluster, A-cluster86 | Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, acetyl-CoA synthase |

| CO2 reduction to Formate and CO, Formate and CO oxidation to CO2 | C-cluster, molybdenum, tungsten, selenocysteine, FMN, Fe–S clusters | Carbon monoxide dehydrogenases, formate dehydrogenases with molybdenum and tungsten, selenocysteine, FMN cofactors, and Fe–S clusters,63,64 formate dehydrogenases with no prosthetic groups.65 |

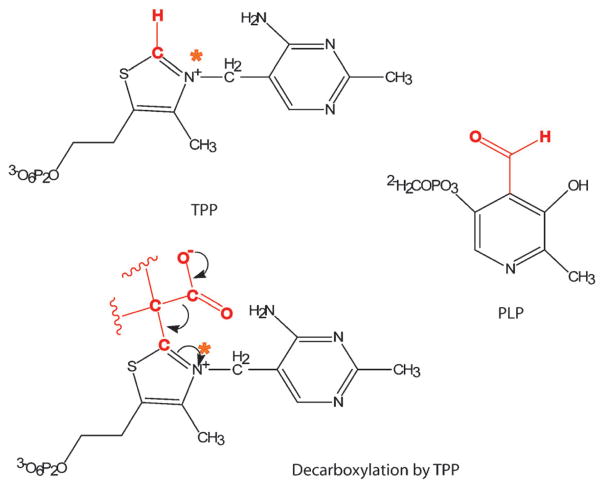

Decarboxylation reactions are facilitated by the electron accepting nature of the groups next to the carboxyl leaving group and this electron accepting nature can be bestowed through cofactors such as thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP). TPP is utilized as a cofactor by α-ketoacid decarboxylases and oxidoreductases whereas PLP is used more often by amino acid decarboxylases. The structures of these cofactors and the mechanism of a generic TPP-catalyzed decarboxylation are depicted in Fig. 6. These decarboxylation reactions have been studied to a high degree and many of the intermediates have been identified spectrophotometrically and by crystallography.55 Both types of cofactors and the carboxyl group eliminations that they catalyze involve intermediates where the substrates are covalently bound to the cofactor. Many of the reactions also have radical intermediates, as exemplified by PFOR,56 which is described later in this review.

Fig. 6.

The structures of TPP and PLP with the reactive sites highlighted in red. A typical decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by TPP-bound intermediate is also depicted, with the orange star indicating the same nitrogen as on TPP structure.

Decarbonylation is involved in various enzymatic reactions. The decarbonylation reaction of ACS is discussed in detail below. During maturation of the hydrogenase active site, the CO ligand for the H-cluster of the Fe–Fe dependent hydrogenases is derived from tyrosine.57 During degradation of the porphyrin ring of heme, heme oxygenase releases CO, which serves as a signaling molecule for different physiological processes.58 Other enzymes that release CO as a product are 3-hydroxy-4-oxoquinoline-2,4-dioxygenase,59 quercetin-2,3-dioxygenase,60 octadecanal decarbonylase61 and acireductone dioxygenase.62 In other reactions, CO is a substrate. CODH can oxidize CO to CO2 and ACS uses CO as one of the three substrates to synthesize acetyl-CoA.15

CO2 is also reduced to formate by formate dehydrogenase according to the following equation:

| (3) |

There are different types of formate dehydrogenases, including molybdenum and tungsten-dependent ones, with selenocysteine, FMN, and Fe–S clusters as additional cofactors.63,64 Some formate dehydrogenases do not have prosthetic groups.65 Formate dehydrogenase is a metabolically important enzyme for many different organisms because it catalyzes the initial incorporation of CO2 into cellular metabolism through reduction to formate. There is also variability in the electron acceptors used by this enzyme. Formate dehydrogenases from aerobic, anaerobic bacteria, yeast and plants can use NAD+ or NADP+ as electron acceptors. Anaerobic formate dehydrogenase complexes contain molybdenum, tungsten, selenium, Fe4S4 clusters, and heme b as cofactors and electron transport centers, and can reduce membrane bound molecules such as menaquinone, cytochromes in E. coli or F-420 in methanogenic bacteria.66–69 Formate dehydrogenase from Moorella thermoacetica reduces CO2 by using electrons from NADPH. Nitrate reduction in E.coli is coupled to the formate dehydrogenase activity and presence of cytochromes in wild type cells.70

(A) CO oxidation

As mentioned earlier, some organisms are able to use CO as a source of electrons and carbon. Many other microbes are able to catalyze the oxidation of CO while growing on other carbon and energy sources. The known CO oxidizers are summarized in Table 3 and the reactions they catalyze are described in the following sections.

Table 3.

List of CO-oxidizers.

| Electron acceptor | Autotrophic pathway | CODH | Taxonomic group | Example organisms | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanogenic Archaea | CO2 reduction to methane | Wood-Ljungdahl | NiFe CODH (IV–V)a | Euryarchaea | Methanosarcina barkeri, Methanobacterium formicicum, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus | 93 |

| Acetogenic bacteria | CO2 reduction to acetate | Wood-Ljungdahl | NiFe CODH III | Clostridia, deltaproteobacteria, Dehalococcoidetes | Moorella thermoacetica, Clostridium formicicum | 94–96 |

| Purple non-sulfur photosynthesizing bacteria | protons | Calvin cycle | NiFe CODH (I or II) | α-proteobacteria | Rhodopseudomonas, Rhodospirillum rubrum | 97,98 |

| Sulfate reducing deltaproteobacteria | sulfate, sulfite | none | NiFe CODH IV | δ-proteobacteria | Desulfovibrio desulfuricans | 99–101 |

| Aerobic carboxydobacteria | O2 | Calvin cycle | Mo CODH | Many Gram-negative bacteria | Oligotropha (formerly Pseudomonas) carboxydovorans | 71,102 |

| Non-acetogenic clostridia | CO2 reduction to formate | none | Not known | Clostridia | Clostridium pasteurianum | 103,104 |

| Plants and algae | O2 | Calvin cycle | cytochrome c oxidase | Viridiplantae | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Arabidopsis thaliana | 105 |

The Roman numerals indicate the closest homologue in C. hydrogenoformans.

(1) A Mo-dependent CODH catalyzes aerobic CO oxidation and CO2 reduction

(a) Aerobic CO oxidizing microbes

Microbial carbon monoxide oxidation was first discovered in aerobic organisms and the term carboxidobacteria has been coined to describe aerobic bacteria with the ability to oxidize CO. The first isolated strain was named Oligotropha carboxidovorans71 to indicate that it eats everything, but devours CO. O. carboxidovorans has been a model organism for studies of aerobic CO oxidation. This organism consumes CO and O2 with a stoichiometry of 2 : 1, as shown in eqn (4).72 The diversity of currently known aerobic CO oxidizers has been reviewed.73

| (4) |

(b) Metallocenters in the aerobic Mo-Cu CODH

The enzyme used for aerobic CO oxidation is a molybdenum-, copper-, iron–sulfur- and flavin-containing hydroxylase that is unrelated to the Ni-dependent CODH found in anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Aerobic CODH is a dimer of hetero-trimers consisting of CoxS, which harbors two Fe2S2 clusters, CoxM, which has non-covalently bound FAD, and CoxL, which contains the molybdopterin active site (Fig. 3). The amino acid sequences of the Cox subunits are most similar to those of molybdenum hydroxylases like xanthine oxidoreductase.74 Buried in the large subunit, the Mo-pterin active site is connected to the surface of the protein by a 17 Å hydrophobic channel. The CODH subunits are arranged so that the two Fe2S2 clusters are between the buried Mo-pterin active site and FAD near the surface.27 X-ray crystallographic studies of a high specific activity (23.2 U mg−1) preparation of O. carboxidovorans CODH (94% active) showed that the active site contains the molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide (MCD) cofactor, molybdenum, and copper (Fig. 3).75 Evidence for this Cu included anomalous difference Fourier maps from data collected at the Se-K- and Cu-K-absorption edges, and detection by EPR of Cu removed from the enzyme upon treatment with CN−. Furthermore, activity is proportional to both Cu and cyanolysable sulfur content.76 The Cu atom is coordinated by the backbone nitrogen and the sulfur of Cys388, and is bridged by an inorganic sulfur atom to Mo. Molybdenum is coordinated by the MCD cofactor and two oxygen ligands, with all five ligands arranged in a distorted square pyramidal geometry. The structure of the active site has been confirmed by a subsequent crystal structures of inactive and fully constituted active CODH,77 and by X-ray absorption spectroscopy.76

(c) Maturation of the active site of the Mo-Cu CODH

The complete sequence of events and set of chaperones required for active site maturation is not known. Genes encoding the three CODH subunits and presumably most of the accessory proteins needed for active site synthesis are found in the cox (for carbon monoxide oxidase) or cut gene cluster. In O. carboxidovorans, the coxBCMSLDEFGHIK gene cluster is transcribed during growth on CO, but not during growth on H2/CO2 or on heterotrophic substrates. Transposonmutagenesis has revealed that coxH and coxI are needed for growth on CO, but not for synthesis of fully active CODH.87 Mutation of coxD leads to expression of an inactive CODH that lacks the Cu and bridging S atoms in the active site, but could be reconstituted to produce active enzyme.88 CoxD was found to be a membrane-bound GTPase, but has not yet been purified.88

Incorporation of Mo depends on its availability in the cell. Excess tungsten (W) inhibits Mo transport into cells89 and, based on X-ray crystallographic studies of CODH from cells grown in the absence of Mo, the molybdopterin portion of the MCD cofactor is missing and only 5′-cytidine diphosphate is present.90

(d) Spectroscopic and Kinetic studies of the Mo-Cu CODH

Based on the Cu-K-edge EXAFS spectra, the oxidized and CO-reduced CODH show nonlinear coordination of Cu by two sulfurs,76 which is consistent with coordination by the Mo–Cu bridging sulfur and by Cys388, as seen in the crystal structure of high-activity CODH.75 Reduction by CO shifts the Mo-K-edge by 1.6 eV, consistent with two-electron reduction of Mo(VI) to the Mo(IV) state. In addition, reduction appears to convert one of the oxo-groups to a hydroxyl and to cause slight changes in the Mo–S distances.

Crystallographic studies of the oxidized, reduced and n-butylisocyanide-treated enzyme suggested a mechanism for CO oxidation.75 The oxidized and reduced active sites have very similar geometries, with a small increase in the distance between Mo and Cu, and between Mo and its hydroxo-ligand. In the structure with bound n-butylisocyanide, the CN moiety was inserted between Cu and the metal-bridging sulfur, with C bound to sulfur and to the Mo hydroxo-ligand, and N coordinated to Cu, suggesting that CO similarly inserts within the Cu–S bond. It was suggested that the next step in the reaction involves electron transfer through sulfur to Mo and attack by the Mo-bound OH to form a S–CO2 species. On the other hand, two computational studies indicate that the proposed S–CO2 is not a catalytic intermediate, that CO would bind to Cu without the insertion between Cu and S, and that the Cu–S bond could remain intact throughout the catalytic cycle. Both studies proposed the bisoxo form of Mo (rather than Mo coordinated by oxo and hydroxo ligands) as the species needed for formation of the C–O bond.91,92

Two recent kinetic studies address the reductive and oxidative half reactions of O. carboxidovorans CODH.106,107 The kcat was determined to be 93 s−1 and the Km for CO is 11 μM (at the optimal pH of 7.2). Studies of the reduction by excess CO show that CO binds rapidly, then undergoes rate-limiting oxidation that leads to reduction of the two iron–sulfur clusters at a rate constant (~90 s−1) that is similar to the value of kcat. The absorbance changes from FAD indicate that the two-electron reduction of FAD involves a flavin semiquinone intermediate.106 Quinones, not cytochromes, are the likely physiological electron acceptors.107

(2) CO/CO2 conversion by the Ni-CODH in anaerobic microbes

(a) Cellular roles of different Ni-CODHs

Like the aerobic enzymes, the anaerobic Ni-CODHs catalyze reaction (1). The Ni-CODH enables these organisms to grow on CO as the sole source of carbon and energy.96,108 In the cell, different CODHs are used for CO oxidation or for CO2 reduction. The varied functions for CODHs are exemplified in C. hydrogenoformans, which encodes five CODHs that have been placed into separate sub-families by phylogenetic analysis,109 with sequence identity as low as 30% between the most distantly related pairs of sequences across these sub-families. Three of the five C. hydrogenoformans CODHs have been purified and characterized. CODH I and II, which share 59 percent sequence identity, are localized at the inner side of the cytoplasmic membrane, but are apparently very loosely associated with the membrane.20 Based on reconstitution of CO-dependent H2-evolving activity, CODH I appears to couple CO oxidation to H2 formation by a membrane-bound hydrogenase, which is hypothesized to generate a transmembrane H+ gradient for ATP synthesis.110 CODH II was hypothesized to couple CO oxidation to reduction of cellular electron carriers, based on its ability to stimulate CO-dependent NADP+ reduction in cytoplasmic fractions.20

CODH III shares 49% and 46% sequence identity to CODH I and II, respectively, but its sequence109 is most similar to the well-characterized CODH (acsA) from M. thermoacetica111 that is involved in the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway and is part of the acs gene cluster, which also contains ACS, the CFeSP subunits and methyl transferase.112,113 This type of CODH can reduce CO2 to CO, which ACS utilizes for acetyl-CoA synthesis, or oxidize CO, thus donating electrons to cellular redox carriers. Homologous genes occur as an operon in methanogenic archaea.114,115 In M. thermoacetica, CODH is isolated in a complex with ACS,116,117 while, in at least some methanogens, a large acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase (ACDS) complex can be purified that includes CODH, ACS, both subunits of the CFeSP and a small subunit that tightly associates with the CODH subunit.118,119 Some methanogenic archaea can oxidize CO when they express the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway to oxidize acetate to obtain electrons for methanogenesis.120–123

CODH IV and CODH V from C. hydrogenoformans have not been purified, and their cellular roles have not been defined. Based on surrounding genes, CODH IV is hypothesized to play a role in responding to oxidative stress. The sequence of CODH V differs most from the other CODH sequences, and its gene neighborhood does not indicate its physiological role.109

(b) CO sensing mechanisms in microbes, CooA & RcoM

Some microbes contain a CO sensor that activates transcription of genes involved in CO metabolism. The CO-sensor that has been studied and understood the most is CooA from Rhodospirillum rubrum.124 CooA is a heme-binding protein. When CO binds to the heme cofactor, it causes a conformational change that leads to DNA binding.125 Some homologues of CooA are present in other organisms, such as the transcriptional activator, CRP of E. coli, even though they respond to different effectors and have different physiological roles. There are also more closely related homologs in organisms that are either known to or expected to utilize CO, but none of them have been as biochemically well-characterized as CooA. The bacteria in which the CooA analogs were found were Azotobacter vinelandii, Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans strains, and Desulfuvibrio species.126 CooA not only senses CO, but it is also a sensor of redox potential, since it is reduced below −300 mV and can only bind CO in the reduced form. There is a ligand switch between the oxidized (Cys ligand) and reduced (His ligand) forms of the enzyme while CO replaces the other axial ligand, Pro.124

Another CO responsive transcriptional regulatory protein called RcoM has been idenified in various facultative aerobic microbes.127 Like CooA, RcoM binds heme; however, the heme binds to a PAS instead of a CRP-like domain.

(c) Metal-centered cofactors of the Ni-CODH

Over the last decade, several CODHs have been crystallized, including the R. rubrum CO-induced CODH,128 CODH II from C. hydrogenoformans,129 the CODH/ACS complex from M. thermoacetica44,130 (Fig. 4) and the CODH component of the ACDS complex of Methanosarcina barkeri.131 The structures of the M. thermoacetica CODH overlay with those of the CODHs from R. rubrum and C. hydrogenoformans with root mean square deviations of 1.0 and 0.8 Å, respectively.44 All of the bacterial CODHs crystallize as homodimers in which each subunit contains the unique NiFe4S4 active site (the C-cluster), an Fe4S4 B-cluster, and an additional Fe4S4 cluster, the D-cluster, which bridges the two subunits. An N-terminal helical domain ligates the B- and D-clusters and two (a central and a C-terminal) α/β Rossmann domains provide the ligands for the C-cluster. The Rossmann domains overlay with a root mean square deviation of 1.7 Å.129 The M. barkeri CODH contains the three domains found in the bacterial CODHs along with very similar B-, C- and D-clusters, but in addition, has another domain that ligates two additional Fe4S4 clusters, and an ε-subunit, which is not found in bacterial CODHs and has an unknown function.131

(d) Structure and Maturation of the active site C-cluster of the Ni-CODH

The basic composition of the C-cluster (Fig. 4), which has been seen in X-ray crystal structures of CODH I, II and III from different organisms, is a Fe3S4 cluster, ligated by three cysteine residues, and connected to a binuclear NiFe site. Exhibiting approximately planar or distorted tetrahedral coordination, the Ni is bridged to two sulfurs of the Fe3S4 moiety and coordinated by a fourth cysteine. The Fe of the NiFe site is called ferrous component II (FC II) and is ligated by a histidine and a fifth cysteine ligand that forms a μ3-S coordination at one corner of the cubane. In the first structure of the C. hydrogenoformans CODH II129 an additional inorganic S was modeled as a bridge between Ni and FC II. The importance of the μ2-S bridging Ni and Fe is not clear, although in a recent crystal structure of CO2,132 water, and cyanide133-bound CODH, the bridging sulfur is not present, and instead CO2 and cyanide are bound to Ni and water/hydroxide are bound to Fe.132 In the R. rubrum CODH structure,128 a Cys residue (Cys 531 in Fig. 4c) bridges Ni and FC II, while in the M. thermoacetica CODH/ACS structure,130 this cysteine is modeled in different positions, depending on whether it coordinates Ni or FC II. These last two structures also have a small molecule, modeled as CO, in the apical coordination site of Ni.

The CODH/ACS gene cluster in bacteria contains two small genes, cooC and acsF, that are hypothesized to play a role in active site maturation. In R. rubrum, which encodes only monofunctional CODH, cooC is found in a cooCTJ gene cluster. Deletion of portions of this gene cluster increases the concentration of Ni needed for CO-dependent growth.134 CooC has been purified from R. rubrum. It has a nucleotide-binding domain, which supports ATPase and GTPase activities. Cell-extract experiments with wild-type and deletion strains showed that insertion of Ni into Ni-deficient CODH from R. rubrum could be enhanced, in an ATP dependent fashion, by CooC.135

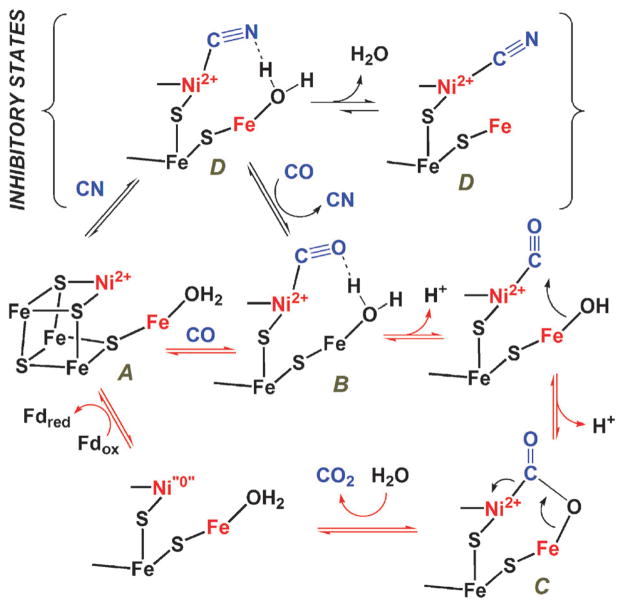

(e) Bimetallic Ni-CODH mechanism

Early studies on CODH from Rhodospirillum rubrum showed that Ni and FeS clusters are both involved in CO oxidation.136,137 Spectroscopic studies demonstrate that the C-cluster can equilibrate among at least three different oxidation states: Cox, which is EPR-silent and Cred1 (gx,y,z = 2.01, 1.81 and 1.65, gav = 1.82) and Cred2 (gx,y,z = 1.97, 1.87 and 1.75, gav = 1.86), which are EPR active. In M. thermoacetica CODH, Cred1 is formed by one-electron reduction of Cox, with a midpoint potential of −220 mV, and Cred2 is formed upon lowering the redox potential to around −530 mV.138 When CODH is treated with CO, Cred1 is rapidly converted into Cred2; then the g = 1.94-type EPR spectrum (gx,y,z=2.04, 1.94, 1.90) of the B-cluster is observed.139 Similar changes occur when CODH is reduced by dithionite or Ti(III)citrate with formation of the Cred2 EPR signal from the C-cluster and the g=1.94 spectrum of the B-cluster.138

As described in Fig. 7, CODH uses a ping-pong mechanism.116,140 In the first half-reaction, CO reduces CODH, forming CO2 and, in the second half-reaction, an electron acceptor binds and reoxidizes CODH. Even with the M. thermoacetica enzyme that has low activity relative to the C. hydrogenoformans enzyme, the reaction with CO occurs so quickly that the temperature needed to be lowered to 5 °C to follow the freeze quench EPR and stopped flow experiments. The first observable changes occur on the C-cluster as Cred1 is converted to Cred2 with a rate constant of 400 s−1 (equivalent to 12 000 s−1 at the optimal growth temperature of 55 °C), yielding a bimolecular rate constant of 4.4 × 106 M−1 s−1 at 5 °C (1.4 × 108 M−1 s−1 at 55 °C). Next, the B-clusters are reduced with a rate constant of 60 s−1 (at 5 °C and 180 μM CO). The kcat for CO oxidation at 5 °C is 47 s−1 by the M. thermoacetica CODH,139 while it is 600 s−1 at 55 °C and pH 7.6.140 The spectroscopic properties of the C-cluster and CO oxidation rate are pH dependent. The gav = 1.82 EPR spectrum of the Cred1 form of CODHMt shows pH-dependent broadening, with an inflection point at pH 7.2. Both kcat and kcat/Km(CO) are pH dependent, with pKa values at 7.7 for kcat/Km and at 7.0 and 9.5 for kcat.140

Fig. 7.

Proposed CODH mechanism incorporating the information from recent crystal structures, based on Kung et al., 2010.141

CO oxidation appears to occur at the NiFe subcomponent of the C-cluster via a bimetallic mechanism as described in Fig. 7. Step 1 involves binding of CO to the Ni site of the C-cluster, as suggested by X-ray crystallographic studies of CO bound to a methanogenic CODH131 and by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR),142 X-ray absorption143 and X-ray-crystallographic133,144 studies of the complex of CODH with CN−, a competitive inhibitor with respect to CO.145 Two modes of CO and CN− binding have been observed: one with an acute Ni–C–N/O angle131,133 and another that is linear.144 The existence of two Ni–CN conformations is consistent with the observations of CN− as a slow binding inhibitor143,145,146 and of two M-CN vibrations in the IR spectrum (at 2078 cm−1 and 2037 cm−1),147 with the former peak at the expected position for a linear Ni–C–N complex and the latter for a bent complex. Step 2 involves the deprotonation of bound water. His and Lys residues are involved in proton transfer during catalysis.148 The metal–OH2 complex should have a fairly low pKa, as in carbonic anhydrase,149 facilitating formation of an active hydroxide. Deprotonation of water may also involve base catalysis by Lys or His residues near the C-cluster,128,129 a proposal supported by mutagenesis experiments.148 In Step 3, OH− from the Fe-hydroxide attacks Ni–CO to form a carboxylate that bridges the Ni and Fe atoms.132 In Step 4, elimination of CO2 is coupled to two-electron reduction of the C-cluster (Ni“0”) and the binding of water. The two-electron reduction could generate a true Ni0 state150 or, more likely, a state in which the electrons delocalize into the Fe and S components of the C-cluster. Freeze quench EPR studies show that when the resting state of CODH (Cred1) reacts with CO, it converts rapidly (1.4 × 108 M−1 s−1) to another distinct paramagnetic state called Cred2, before electrons are transferred to the B- and D-clusters.139,151 Finally, in Step 5 electrons are transferred from the reduced B- and D-clusters to an external redox mediator, e.g., ferredoxin. At high CO concentrations, Step 5 becomes rate limiting.139,151 Each of the steps above can occur in reverse to catalyze the reduction of CO2.

(f) Electrochemical studies of the Ni-CODH

CODH can catalyze CO2 reduction with little to no overpotential. When CODH was directly attached to a glassy carbon working electrode and cyclic voltammetry was performed in the presence of CO2 and methyl viologen, CO was formed at a rate that is half maximal at a redox potential of −0.57 V at pH 6.3, which was very close to the theoretical potential of the CO2 reduction at this pH (−0.48 V).152 Similarly, the midpoint potential for the one-electron reductive activation of the R. rubrum CODH (adsorbed to a pyrolytic graphite electrode) is −418 mV.153 When the C. hyrogenoformans Ni-CODH I was adsorbed on a pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) electrode in an anaerobic cell, it was active in both directions with the electrocatalytic reaction being dependent on both the pH and CO/CO2 concentrations.154 At low pH values, the rate of CO2 reduction surprisingly exceeds that of CO oxidation.154 The high catalytic efficiency of CO2 reduction at the thermo-dynamic potential for the CO2/CO couple appears to be due to its ability to undergo rapid successive two-electron transfers coupled to proton transfer,154 unlike nonenzymatic catalysts that reduce CO2 through a high-energy •−CO2 anion radical.155 Electrochemical studies also revealed two reversible processes with activation/inactivation potentials of −50 mV and −250 mV.154

CODH can be coupled to other electrochemical reactions. For example, when CODH was adsorbed on graphite platelets along with E. coli hydrogenase, H2 was produced, coupling CO oxidation to proton reduction.156 This is analogous to the industrial water gas-shift reaction (eqn (2)). CODH could also be coadsorbed with an inorganic ruthenium complex onto TiO2 nanoparticles, allowing the photoreduction of CO2 to CO using very mild reductants.157

(3) Metal centers involved in energy conservation by CO-utilizing bacteria

(a) Metallocenters involved in energy conservation coupled to CO oxidation in aerobic microbes

Aerobic bacteria oxidize CO using O2 as a final electron acceptor, according to the overall reaction shown in eqn (4). The respiratory chain used during aerobic growth on CO involves direct reduction of the quinone pool by the FAD bound to CODH,107 which would pass electrons to the membrane-bound electron transport chain, including cytochromes.107 It is interesting that growth and respiration of most aerobic bacteria (including carboxidovores!), are inhibited by CO, because CO binds to and inhibits the cytochromes of the terminal oxidase of the respiratory chain. To circumvent CO poisoning of their respiratory chains, carboxidotrophic bacteria, including Pseudomonas, Alcaligenes, and Arthrobacter, have evolved a CO-insensitive terminal oxidase that contains cytochrome o (cytochrome b653) that does not bind CO.158 Thus, at least in P. carboxidovorans, a CO-sensitive cytochrome a-containing cytochrome c oxidase is used during oxidation of heterotrophic substrates, while the CO-insensitive cytochrome o-containing cytochrome c oxidase is used during oxidation of CO or H2.159,160 Thus, the energy conserving electron transfer chain would involve CODH, the quinone, cytochrome c, and the cytochrome o-containing terminal oxidase. Proton translocation that would be coupled to ATP synthesis presumably occurs with the oxidase that links the quinone to cytochrome c and the terminal oxidase. Similar branched respiratory chains have been found in many H2-oxidizing proteobacteria.161

(b) Metallocenters involved in energy conservation by anaerobic growth on CO

Some anaerobic microbes like acetogens are able to use the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway for energy conservation as well as carbon assimilation during autotrophic growth on H2/CO2 or CO.96 M. thermoacetica has phospho-transacetylase162 and acetate kinase, which convert acetyl-CoA to acetate and ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation. However, ligation of formate to tetrahydrofolate in the methyl branch of the pathway requires ATP,163 so there is no net synthesis of ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation by the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. Therefore, acetogens growing autotrophically by this pathway must synthesize ATP by gradient-driven ATP synthases.

The oxidation of CO in M. thermoautotrophica is coupled to reduction of the b-type cytochromes present in the membranes in a process that involves methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase.164 The following electron transport chain has been proposed: oxidation of CO coupled to reduction of cytochrome b559, which then reduces methylenetetrahydrofolate or menaquinone and cytochrome b554, which would finally reduce rubredoxin.165 However, the step that extrudes protons in the proposed electron transport chain is still not known. The free energy change of reduction of methylene-tetrahydrofolate to methyl-tetrahydrofolate (ΔG0′ = −57.3 kJ mol−1) would be sufficient for ATP synthesis.166 A proton-pumping F1F0 ATPase is found in M. thermoacetica.167,168 M. thermoacetica membrane vesicles prepared by gentle lysis of cells, which does not disrupt the association of CODH with the membrane, can generate a proton motive force when exposed to CO.169

While some acetogens like M. thermoacetica seem to use a cytochrome-based proton-coupled electron transfer pathway, others, like Acetobacterium woodii contain membrane-bound corrinoids instead of cytochromes that have been suggested, in analogy to the corrinoid-containing, Na+-pumping methyltetrahydro-methanopterin: coenzyme M methyltransferases of methanogenic archaea, to be involved in energy conservation.170,171 Experiments with resting cells of A. woodii have shown that the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase requires sodium, and is probably the electron-accepting step for Wood-Ljungdahl pathway-linked respiration.172 Na+ is taken up into inverted membrane vesicles, which is coupled to acetogenesis.173 The Na+ dependent ATPase was purified and shown to be an unusual F1F0 ATPase,174 with two types of rotor subunits, e.g., two bacterial F(0)-like c subunits and an 18 kDa eukaryal V(0)-like c subunit.175,176 Acetate formation and autotrophic growth by A. woodii require sodium.172 Given the phylogenetic diversity of acetogens, there may be many different mechanisms for coupling oxidation of other substrates to ATP synthesis during acetogenic growth and many different proton or sodium-translocating enzymes. One mechanism that has been recently shown is coupling of H2 oxidation and caffeate reduction to ATP synthesis in A. woodii by an Rnf-type NADH dehydrogenase complex that accepts electrons from ferredoxin and reduces NAD+ (NADH is the electron donor for caffeate reduction), while translocating Na+.177,178 Sodium transport in this systemis supplemented by a sodium translocating pyrophosphatase that uses PPi generated when ATP is cleaved to activate caffeate.179 Whether these Na+ translocating systems are also coupled to the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is not yet known. A second route for energy conservation during anaerobic growth on CO is coupling CO oxidation and proton reduction to H2 by separate enzymes to ATP formation as described above for C. hydrogenoformans CODH I.

(B) PFOR and the production and utilization of CO2

PFOR catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to form acetyl-CoA, CO2 and two reducing equivalents, which are transferred to ferredoxin:

| (5) |

PFOR also catalyzes the thermodynamically uphill reverse reaction to generate pyruvate,180,181 which enters the reductive TCA cycle182,183 to generate intermediates for cell carbon synthesis. Found in archaea, bacteria, and anaerobic protozoa,184 PFOR is the target for nitroimidazole drugs, e.g. metronidazole and tinidazole, which target various infectious anaerobic microbes, including Clostridium difficile (diarrhea) and Helicobacter pylori (ulcers).185,186

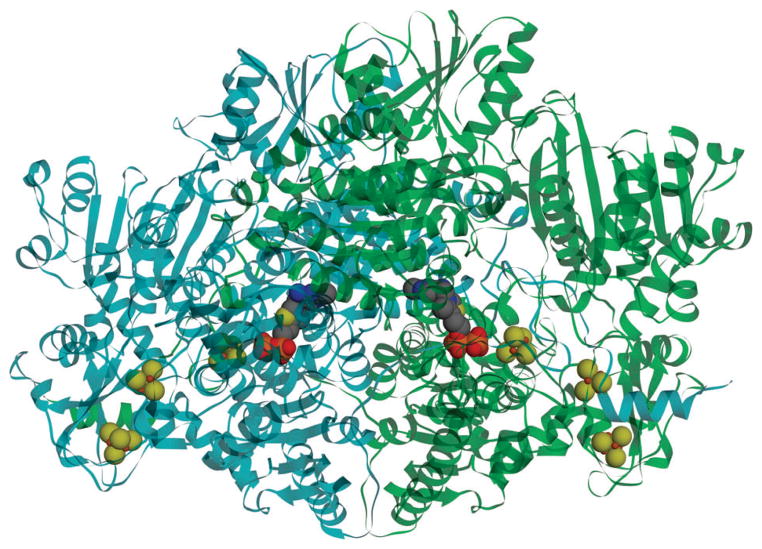

PFOR and other oxoacid oxidoreductases can be homodimeric, heterodimeric or heterotetrameric187 and appear to have evolved by rearrangements and fusions of four ancestral genes.188,189 The Desulfovibrio africanus PFOR, whose structure is known,190 is homodimeric like the highly homologous M. thermoacetica protein, the fusion product of all four genes. As shown in Fig. 8, PFOR contains thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) and three Fe4S4 clusters per monomeric unit, with TPP and Cluster A being deeply buried within the protein and the other two clusters (B and C), which are in a ferredoxin-like domain, leading to the surface, where interactions with a redox partner such as ferredoxin can occur. Clusters A–B and B–C are separated by ~13 Å (center-to-center) and exhibit midpoint redox potentials of −540, −515, and −390 mV.191

Fig. 8.

The main cofactors and the overall structure of Desulfovibrio africanus pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from pdb:1B0P, shown in sphere and ribbon representation respectively. The enzyme is a homodimer (cyan and green chains), and each monomer contains one TPP and three Fe4S4 clusters (spheres).

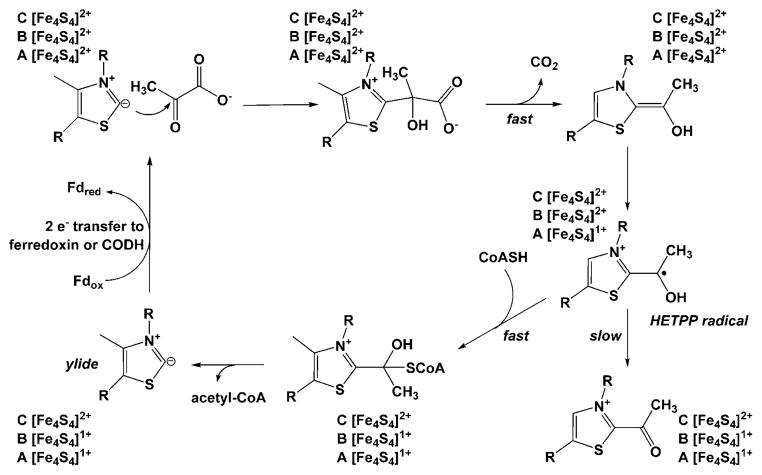

The PFOR mechanism (Fig. 9) has been studied by transient and steady-state kinetic studies.192 Carbon 2 of the thiazolium ring of TPP undergoes deprotonation to generate an ylide, which catalyzes nucleophilic attack on the C2 atom of pyruvate, generating a lactoyl-TPP adduct that undergoes decarboxylation to generate a 2α-hydroxyethylidene-TPP (HE-TPP) intermediate. HE-TPP is a highly reactive carbanion (“active aldehyde”) that undergoes a one-electron transfer from Cluster A to Cluster B, thus generating a HE-TPP radical intermediate. The HE-TPP radical, recently assigned incorrectly as a sigma radical based on X-ray crystallographic studies,193 has been shown to be a pi-type radical benefiting from stabilization among at least 7 different resonance forms, with the unpaired spin delocalized among the atoms of the HE group and the thiazole ring.194 The HE-TPP radical then transfers one electron to an internal Fe4S4 cluster in a reaction that binding of CoA enhances by 105-fold,192,195 with the thiol group of CoA alone lowering the barrier for electron transfer by 40.5 kJ/mol.192 Finally, the reduced enzyme transfers two electrons to ferredoxin.

Fig. 9.

PFOR mechanism.192 See text for further explanation of the steps of the reaction mechanim.

Pyruvate oxidase appears to follow a mechanism similar to that of PFOR, with phosphate taking the place of CoA and molecular oxygen replacing ferredoxin as electron acceptor. This enzyme contains TPP, FAD, Mg2+ and Mn2+ and generates acetyl-Pi and H2O2 as products.55,196,197

(C) The CFeSP and methyltransferase (MeTr)

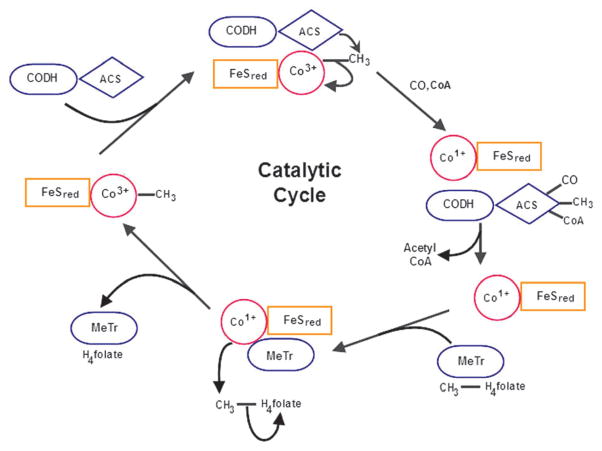

MeTr (AcsE)162 catalyzes transfer of the methyl group of CH3–H4folate to the Co(I) center in the CFeSP (AcsCD)198,199 to form the first organometallic intermediate in the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, CH3–Co(III) (Fig. 2). In this reaction, the CFeSP acts as the methyl acceptor and methyl-H4folate acts as the methyl donor. The reaction takes place via an SN2 mechanism in which the cob(I)amide state of the CFeSP engages in a nucleophilic attack on the methyl group of methyl-H4folate, forming the methylcob(III)amide state of the CFeSP and releasing H4folate.200 This reaction appears to occur via the following steps, as shown in Fig. 10. First, there is a pH-dependent conformational change in the protein.201 MeTr then binds methyl-H4folate and the CFeSP in a random mechanism.202 At this point, methyl-H4folate is protonated from solvent at the N5 position (where the methyl group is bound) through an extended H-bonding network that involves an Asn residue that interacts with N5.203 This protonation places a positive charge at N5, activating the methyl group and making the methyl donor more electrophilic.200,204 The methyl group is then transferred to CFeSP. MeTr, H4folate, and the methylated CFeSP rapidly dissociate after methyl transfer occurs, ending the first phase of the CFeSP-catalyzed reaction.204

Fig. 10.

The catalytic cycle of CFeSP and its interactions with CODH/ACS and MeTr.

After dissociation from the ternary complex formed in the first methyl transfer reaction, the methylated CFeSP serves as the methyl donor to ACS205 in a reaction that is described in more detail below. Briefly, the Ni center of the A-cluster of ACS engages in an SN2 attack on the methylcob(III)amide, which methylates ACS and regenerates Co(I) for the next round of catalysis by MeTr.206 Then, the methyl-Ni form of ACS undergoes a carbonyl insertion to produce an acetyl-Ni intermediate that undergoes nucleophilic attack by CoA to generate acetyl-CoA.207

(D) CO as a metabolic intermediate during growth on CO2

When acetogens grow on pyruvate, CO is formed as a metabolic intermediate that is generated by the combined actions of PFOR, which catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate, and CODH, which reduces the CO2 to CO.208 Carbon monoxide has also been shown to be produced during growth of aceticlastic methanogens.209 The CO that is generated, however, is sequestered within a channel in the CODH/ACS complex as revealed by enzymatic studies210,211 and by X-ray crystallography.44,212,213 When CODH/ACS crystals were subjected to high pressures of Xenon gas, Xe atoms were located at 19 discrete sites in the protein, allowing one to map out a path for the CO molecules between the active sites.212 Mutations of residues to block the movement of CO in the channel led to enzymes with much lower CODH and ACS activities.214 A similar gas channel was observed in the crystal structure of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex of aceticlastic methanogens.215 The presence of a CO channel underlines the problem of the low availability of CO in the environment and the need to sequester the produced CO and not lose it to irrelevant reactions or to diffusion out of the cell.

(E) The synthesis of acetyl-CoA by ACS

(1) The structure of ACS

ACS is a nickel protein that is involved in the final step of acetyl-CoA synthesis from CO generated by CODH, the methyl group donated by the CFeSP, and CoA. ACS consists of three domains.15,141,216,217 The N-terminal Rossmann-fold domain interacts with the CODH subunit and contains part of the CO channel, described just above. The next two domains have novel α/β folds, and the C-terminal domain contains the A-cluster. In addition, there is an interdomain cavity rich in Arg residues that is proposed to be the binding site for CoA. During catalysis, the three domains appear to undergo large conformational changes relative to each other to accommodate the three substrates with very different sizes and coming from different directions to the active site. For example, to transfer a 15 Da methyl group from the 88 kDa CFeSP to the A-cluster makes it imperative that the ACS subunit open up to bring the A cluster and Co(III)-CH3 of the CFeSP within bonding distance.

(2) Structure of the A-cluster

When CODH/ACS was first analyzed by EPR, the CO-treated reduced enzyme was found to exhibit a characteristic EPR spectrum with g-values at 2.074 and 2.028.218 When 13CO was used and when the enzyme was labeled with 61Ni and 57Fe, hyperfine splittings were observed, indicating that CO binds to a Ni-FeS cluster containing more than two iron atoms and that there is extensive delocalization of the unpaired electron spin among these components of the cluster; therefore, this signal was named the NiFeC signal.218–220 Subsequently, it was found that this signal derives from the A-cluster in ACS, which consists of a Fe4S4 cluster that is cysteine-bridged to a dinuclear Ni center (Fig. 4d). Cys506, Cys518 and Cys528 (numbering based on M. thermoacetica) ligate to the iron sites in the Fe4S4 cluster and Cys509 bridges the Fe4S4 cluster and the Ni that is proximal to the Fe4S4 (Nip). Nip is ligated by two other Cys residues, Cys595 and Cys597, which bridges Nip to the distal nickel (Nid). The other Nid ligands are the backbone amide groups of Cys595 and Gly596, forming a square planar coordination and a stable +2 oxidation state for Nid.44

Initially, the metal in the proximal position was thought to be Cu because Cu was present at high occupancy in the first crystal structure (with Ni in the distal site); furthermore, activity appeared to be correlated to Cu content.221 However, it later became apparent that a reconstituted Ni–Ni form of the A-cluster was active, while a Cu–Cu form was not.222 Metal reconstitution experiments (using Cu2+ and Ni) with the acetogenic enzyme also indicated that the Cu–Ni form of ACS is inactive and the Ni–Ni form is active.223 When methods were developed to examine activity over a wide range of Ni, Cu and Zn concentrations, it became clear that Cu and Zn readily substitute into the Nip site, and that the Ni–Ni enzyme is the active form of the enzyme.224 The monomeric ACS from C. hydrogenoformans also contains two Ni atoms, and the activity of the enzyme correlates well with the nickel content of the monomer.225

X-Ray crystallographic and biochemical studies revealed that the coordination chemistry and/or the metal in the proximal site can affect the conformation of the protein, i.e., the Ni–Ni form of ACS has an open conformation whereas Zn–Ni has a closed conformation.213,226 The different conformations observed with different metals indicate a high degree of plasticity at the Mp site, which would help promote alternative coordination and oxidation (Ni1+,2+,3+) states as ACS performs a catalytic cycle, e.g., having a closed conformation to react with CO and an open conformation to react with the methylated corrinoid protein.

It is not known if chaperone proteins are involved in metal incorporation or maturation of the A-cluster. It was proposed that AcsF, encoded by one of the genes of the acs gene cluster, is involved in the insertion of Ni into the active site.227

(3) Assays and Proposed mechanisms for acetyl-CoA synthesis—the diamagnetic and paramagnetic mechanisms

In describing the mechanism of ACS, there are three major controversial and interrelated issues: (i) whether the catalytic cycle occurs through diamagnetic or paramagnetic intermediates, (ii) whether the active state of the A-cluster is a Ni0, Ni1+, or Ni2+ species or a spin-coupled center in which Ni1+ is coupled to a Fe4S4 cluster, and (iii) whether the first step in acetyl-CoA synthesis is carbonylation or methylation. Different views on these issues were addressed in a series of reviews.217,228–230 Whatever mechanism is proposed, it must not conflict with the following experimental results: (i) Isotope chase experiments indicate that CO and the methyl group bind randomly to ACS to form an acetyl-ACS intermediate that reacts with CoA to form acetyl-CoA.231 Thus, methyl-ACS and ACS-CO are both viable intermediates in the pathway of acetyl-CoA synthesis. This is consistent with experiments indicating that methylated205,232 and carbonylated233 forms of ACS are intermediates. (ii) The activation of ACS involves an n =1 process with an activation potential near −500 mV. Controlled potential enzymology studies measure midpoint potentials of −490 mV for the CoA/acetyl-CoA exchange234,235 and −510 mV for the CO/acetyl-CoA exchange.236 (iii) Transfer of the methyl group to CODH/ACS occurs by an SN2 pathway206 and the methyl-ACS product does not appear to exhibit an EPR signal.229 (iv) The methyl group of chiral CH3–H4folate is converted to acetyl-CoA with retention of configuration.237

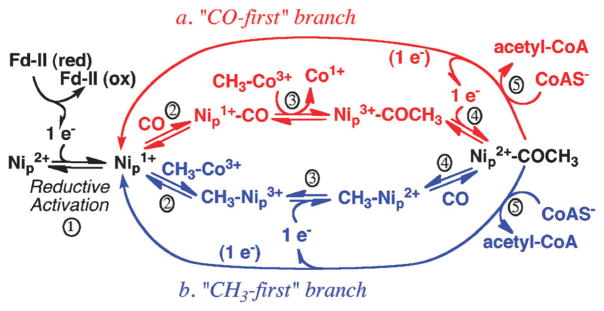

The competing “paramagnetic” and “diamagnetic” mechanisms differ in whether the pathway of anaerobic acetyl-CoA synthesis occurs through paramagnetic or diamagnetic intermediates.86,231,238,239 In the Paramagnetic mechanism, shown in Fig. 11, Step 1 involves reductive activation of Nip2+ to the active Ni1+ state, which can bind CO (“a” branch in red) or the methyl group (“b” branch in blue).207 In step 2a, Nip1+ binds CO to form a paramagnetic Nip1+–CO intermediate. This step can be reversed by photolysis of Nip1+–CO, generating Nip1+, which recombines with CO with an extremely low (1 kJ mol−1) activation energy. The CO used in this step is generated in situ by CODH and channeled to the active site of ACS. In step 3a, ACS binds the methyl group to form acetyl-Ni3+, which is proposed to be rapidly reduced (step 4a) by an internal redox shuttle to form acetyl-Ni2+. Finally, in step 5a, CoA reacts with acetyl-ACS to release acetyl-CoA in a reaction that leads to transfer of one electron to the A-cluster to regenerate the Ni1+ starting species and the other to the electron shuttle, which can reduce acetyl-Ni3+ in the next catalytic cycle. In the lower “b” branch, reductive activation is coupled to methylation (step 2b), then reduction (3b) to generate methyl-Ni2+. Then, CO binds to form the acetyl-ACS intermediate (4b), which reacts with CoA (5b), as in the “a” branch.

Fig. 11.

The proposed mechanism of acetyl-CoA formation by ACS. CO or the methyl group bind randomly, as shown in path a (red) or b (blue), respectively.

The diamagnetic mechanism229 can be related to the lower path (b) except that it includes two-electron reductive activation to generate Ni229,240 or a spin-coupled species with Ni and the cluster in the 1+ states,239,241 methylation to generate methyl-Ni2+, carbonylation to generate acetyl-Ni2+, and nucleophilic attack by CoA to regenerate the active Ni“0” state. The diamagnetic mechanism considers Ni1+–CO to be an inhibited state and lacks the need for an internal electron shuttle. Both the paramagnetic and diamagnetic mechanisms satisfy the stereochemical requirements because they involve two successive nucleophilic attacks, i.e., by Co(I) on methyl-H4folate and by Ni(I) on the methylated CFeSP, which would lead to net retention of configuration.

The binding site for CoA on ACS is not known. Phenylglyoxal, methylglyoxal, and butanedione, which modify arginine residues, are inhibitors of ACS activity; thus an arginine residue appears to be involved in binding of CoA.242 These modifying agents worked in the presence of CO, so CO binding does not block the modification sites. A tryptophan residue has also been implicated in CoA binding; N-bromosuccinamide (NBS) modifies tryptophan residues in CODH/ACS and inhibits ACS activities, and CoA binding protects against this modification and against inhibition of activity by NBS.243 Purification and sequencing of a peptide protected from DNPS-Cl modification by CoA identified Trp418 of the M. thermoacetica ACS as the tryptophan residue most likely involved in CoA binding.244 Trp418 is part of the middle domain of ACS, and faces into a cleft in the center of the protein. Its side chain is about 24 Å from the proximal Ni in the active site, which is contained in the C-terminal domain of the protein. The ATP moiety of CoA may bind to the central domain of ACS, with the pantotheine part of the molecule stretching across the cleft in ACS so that sulfur is positioned near the active site.

(4) Intermediates trapped during the reaction, and their relationship to the two proposed mechanisms

We favor the paramagnetic mechanism. This choice is based on the results of a combination of electrochemical, isotope chase, and transient kinetic experiments. As described above and shown in Fig. 11, either CO or the methyl group can bind to ACS in the first step in acetyl-CoA synthesis. Based on stopped flow IR and freeze quench EPR studies, the only ACS-CO species that forms at catalytically relevant rates is the paramagnetic Ni1+–CO species.233 Ironically, this species was identified by EPR spectroscopy218,219 long before it was even known that CODH and ACS have different active sites. Other transient kinetic studies following formation and decay of the EPR-active Ni1+–CO species also have established its catalytic competence as an intermediate in acetyl-CoA synthesis.245–247 Furthermore, the midpoint potential for formation of the NiFeC species (−540 mV)246 is consistent with the values for reductive activation of ACS in the CO/acetyl-CoA236 and CoA/acetyl-CoA exchange reactions.235

Some favor the diamagnetic mechanism of acetyl-CoA synthesis. Because acetyl-CoA synthesis is inhibited at high CO concentrations, it was suggested that the Ni(I)–CO species might be a reversible, off-pathway species and not an intermediate. 248 However, at non-inhibitory CO concentrations (100 μM), acetyl-CoA synthesis and formation of the Ni(I)–CO species take place at similar turnover numbers (1 s−1) while decay of the species occurs much faster (6 s1−), suggesting that this species is indeed a catalytically competent intermediate.245 The other apparent inconsistency with the paramagnetic mechanism is that the reaction of reduced ACS with the methylated CFeSP generates Co1+ and an EPR-silent product on ACS, indicating it is a CH3–Ni2+ species. The paramagnetic mechanism would predict the initial product of this SN2 reaction would be CH3–Ni3+. Lindahl also showed that ACS can be methylated, purified and stepped through the rest of the reaction without any external reactants or reductants other than CO and CoA (which donates two electrons).249 The methyl-ACS state was also shown to react with the CFeSP to regenerate methyl-Co3+ or with CO and CoA to make acetyl-CoA.205 Thus, if acetyl-CoA synthesis occurs according to the paramagnetic mechanism as shown in Fig. 11, an internal one-electron transfer would be required to reduce CH3–Ni3+ to a more stable CH3–Ni2+ state. Evidence was recently presented for this “one-electron shuttle”.236 It was shown that the shuttle can transfer an electron to ferredoxin, allowing the quantification of the number of electrons in each of the intermediate states of ACS. However, it has not yet been determined where on ACS this shuttle resides.

As shown in Fig. 11, CO or the methyl group are proposed to bind to a Ni1+ species to generate a Ni1+–CO or methyl-Ni3+ species, respectively. Recent studies indicate that this is an unstable intermediate that is transiently formed in a reaction that is kinetically coupled to CO binding. When the Ni(I)–CO state was photolyzed at low temperatures (<30 K), a new EPR signal was observed, which was attributed to the formation of an unstable Ni(I) state in which the CO had dissociated.207 This Ni1+ species has an exceptionally low activation energy for recombination of CO to reform the Ni(I)–CO species. This low activation energy could reflect the recombination of CO from the hydrophobic pocket (an alcove) near Nip observed in the crystal structure.212

Conclusions

Redox-active metal centers are at the catalytic center and the electron-transfer sites of many one-carbon reduction reactions. Over the past decade, there have been many significant findings related to the metabolism of CO2 and CO, which impact our understanding of the biogeochemistry and the evolution of life on Earth. Three novel CO2 fixation pathways have recently been discovered. Structures of many of the key enzymes involved in anaerobic CO and CO2 metabolism have been determined and, with these structures, atomic level descriptions of radicals and metal-centered redox cofactors have been revealed. These include novel molybdenum/copper and nickel–iron–sulfur clusters as well as multiple redox centers that transfer electrons to the catalytic centers. Incisive spectroscopic and kinetic studies have trapped and characterized intermediates bound to these metal centers. Large conformational changes have been shown to move catalytic centers among various binding partners, promoting the transfer of one-carbon units. Channels within proteins have been discovered that facilitate the movement of the reactive high-energy gas CO within a protein complex. Genetic systems have become available that will open the door for site-directed mutagenesis and metabolic studies. Macromolecular complexes that are responsible for energy conservation have been identified.