Abstract

The University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy launched the Bill and Karen Campbell Faculty Mentoring Program (CMP) in 2006 to support scholarship-intensive junior faculty members. This report describes the origin, expectations, principles, and best practices that led to the introduction of the program, reviews the operational methods chosen for its implementation, provides information about its successes, and analyzes its strengths and limitations.

Keywords: faculty mentoring, faculty, scholarship

INTRODUCTION

Much has been written about mentoring and the added value of mentoring programs for faculty development and progression.1-9 A Google citation search conducted in June 2013 using the term “academic mentoring programs” produced 205,000 results. Because of their favorable outcomes, mentoring programs have become a staple of institutional faculty development plans.7 The Bill and Karen Campbell Faculty Mentoring Program (CMP) at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Eshelman School of Pharmacy is an endowed program for the mentoring of junior faculty who choose a scholarship-intensive career track. CMP was based on the belief of Dean William Campbell, an educator with abiding interests in faculty development and the mentoring process, and his wife Karen, a pharmacist, that a structured pharmacy faculty development program would enhance faculty scholarship and increase the vitality of pharmacy faculty members.1 The Campbells recognized the changing landscape of contemporary pharmacy and its increasing reach into the fields of basic, translational, and clinical research, health outcomes, and educational scholarship. They understood that these changes required colleges and schools of pharmacy to institute strategies to assist newly recruited faculty members with diverse backgrounds and often no pharmacy training. Accompanying this national movement of scholarly integration have been the higher expectations that universities have for their junior faculty members in an era of both increased opportunities and increased challenges. Approximately $700,000 was raised in support of the Campbell Fund, and in 2006 the CMP was launched along with funds from the State of North Carolina to total $1 million.10

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The CMP was designed to be uncomplicated and transparent and to require minimal recordkeeping. The CMP has been defined by 4 objectives: to assist in recruiting junior faculty members to UNC by ensuring they have resources for professional growth upon joining the faculty; to help them reach their full potential as rapidly as possible; to help retain them by providing a continuing, caring community; and to capitalize on the talents of senior faculty members in the school and neighboring departments and institutions and involve them in the mentoring process.

The CMP was purposively designed with 6 guiding principles, each of which has proven necessary for the CMP’s success: (1) both junior faculty members and their mentors are invited but not required to participate; (2) as part of the school’s culture, there is a collective responsibility to assist and mentor all faculty members; (3) participation in the CMP (or any mentoring program) is seen as a sign of strength in the new faculty member; (4) mentoring is considered both a formal and an informal activity that can cover all aspects of academic life; (5) junior faculty members must have the opportunity to regularly review their faculty development with their mentors and their division chairs; and (6) the CMP must be flexible to address the changing academic environment.

The CMP’s objectives and principles have led to the establishment of a series of best practices to aid its implementation. The CMP introduces potential junior faculty members to CMP during the interview process, and the opportunity to join is formally extended in the offer letter of employment. Upon accepting an appointment in the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, the director of the CMP meets with the new faculty member to present the CMP in more detail and to learn of the junior faculty member’s needs and interests. If the new faculty member chooses to participate in the CMP, the director creates a mentoring team, so that it will be in place when the junior faculty member arrives.

The CMP stipulates that mentors will guide junior faculty members toward scholarly independence consistent with the objectives of the faculty member’s division chair. The CMP asks that mentors provide timely, scholarly, and methodological advice that promotes and broadens independent study. The CMP further requires that the faculty member’s division chair be part of the mentoring process. Accordingly, the chair is consulted as the mentoring team is established and participates in key yearly assessment meetings with the junior faculty member and his or her mentors. The CMP director also assists and monitors each mentoring team and addresses shortcomings that occur.

Central to the CMP is the mentoring team of 2 mentors assigned to each junior faculty member. The CMP selects mentors who share the scholarship interest of the junior faculty member or are content experts in an area in which he or she expects to grow in the immediate future. The mentors are selected by the director after consulting with the junior faculty member, the division chair, and others in the academic community. The mentors are either associate or full professors. One mentor is selected from the school and the other is from either another UNC school or department or another institution. Based on the director’s experience that a mentor’s physical proximity to the junior faculty member is helpful for interaction, it is preferable to identify mentors within the UNC community.

The 2-person mentoring team is the most important feature of CMP. While most mentoring programs are built around a single mentor and a single junior associate, the approach of the CMP is to embrace the role of the university as part of a broad academic community. Accomplished by selecting a second mentor rooted firmly outside academic pharmacy, this approach serves multiple purposes. It ingrains collaboration as a core academic value in identifying problems and seeking solutions, establishes a nascent intellectual network as a critical resource for all junior faculty members and fosters the development of networking skills, and creates new windows of opportunity throughout the school that could benefit all of its faculty members and programs. Having mentors from 2 different academic areas of the university also permits the junior faculty member to gain insights unique to the school and to discuss sensitive issues with an individual from another area. Experience with the CMP shows that the mentors do not catalyze the junior faculty member’s development without themselves being changed.2,6,11 A mentoring process wherein both the junior faculty member and the mentor change and gain benefit enhances the vitality and the longevity of the relationship.

Along with the mentoring team, the CMP asks other members of the academic community to assist in the mentoring process and become part of the mentoring circle. These include the division chair, the heads of centers or institutes with which the junior faculty member is associated, and the director of the CMP.

The CMP director is the program administrator and reports bimonthly to the vice dean of the school. This reporting structure is strategic, as the vice dean serves as the chair of full professors committee, which makes formal recommendations to the dean on all appointments and promotion and tenure decisions in the school as required by the school’s policies. The director meets annually with both the dean and vice dean to decide which junior faculty members are prepared to successfully leave the CMP. The director is charged with implementing the guidelines and best practices for the CMP and, thus, has multiple responsibilities: (1) introducing the CMP to junior faculty members during the interview process; (2) establishing the mentoring teams, including meeting and interviewing prospective mentors; (3) chairing the initial and yearly junior faculty member’s assessment meetings that include the team, division chair, and center or institute heads; (4) initiating discussions concerning impediments to faculty development; (5) running monthly lunch meetings; and (6) meeting with the participants (junior faculty, mentors, division chairs) when issues emerge that require assistance. Consistent with the CMP’s mission, the director maintains a nationally recognized research group in his area of expertise. The director receives an administrative stipend for managing the CMP, which represents approximately a 15% time commitment.

The mentoring process begins with the inaugural meeting, which is attended by the junior faculty member, his/her 2 mentors, the division chair, the heads of centers and institutes associated with the junior faculty member, and the CMP director. The meeting is chaired by the director but run by the junior faculty member. After consulting with his/her division chair and prior to the meeting, the junior faculty member provides a written list of objectives that covers scholarship, teaching, and service to the mentoring team. This plan consists of a short-range first-year plan and a longer-range, 2-year plan. At the meeting, formal letters inviting the prospective mentors to join the mentoring team are provided by the division chair and CMP director. The junior faculty member, the mentors, and the CMP director all sign an agreement that codifies the relationship with the team and broadly defines the responsibility of the team members (a copy of the agreement is available from the author on request). The agreement allows the school to provide an annual honorarium to each mentor. Many successful academic endeavors that involve mentoring do not pay honoraria. Other mechanisms can be substituted for honoraria,5 but the CMP has found the honorarium to be important not only because it signals to the junior faculty member the CMP’s value to the school, but also because it sets an expectation of quality participation for the program’s mentors. Further, the honorarium demonstrates the school’s appreciation for the mentor’s efforts. At the inaugural meeting, the junior faculty member and mentors are asked to plan for regular meetings in the coming year. The CMP encourages multiple one-on-one meetings per month along with a full-team meeting each month.

On the anniversary of the team launch each year, the CMP invites all who participated in the launch meeting to an assessment meeting. In advance of this meeting, the junior faculty member provides a summary listing his/her accomplishments in the areas of scholarship, teaching, and service for the preceding year, a proposed plan of objectives for these same areas for the coming year, and a list of the roadblocks that hinder progress and development. As with the launch meeting, the CMP director chairs this assessment meeting, but the junior faculty member runs it. The major focus is on the proposed plans, new opportunities, and discussion of potential obstacles. It is the director’s responsibility to lead a discussion about any roadblocks for success and if and how they can be removed. The yearly assessment reports, along with the original launch materials, are the only written documents that the CMP retains in its files. The director meets with each junior faculty member at least once each year to discuss issues unique to his/her development. Meetings are also arranged whenever issues arise that would benefit from immediate discussion.

The director sponsors a monthly, informal luncheon with the junior faculty members and an outside guest expert; this luncheon does not include mentors. At each luncheon, an issue important to junior faculty members is addressed. Topics for the 2012–2013 academic calendar included: (1) the school’s educational renaissance initiative and the importance of active learning; (2) promotion and tenure decisions from the reviewer’s perspective; (3) how the UNC Center for Faculty Excellence can help; (4) lessons the junior faculty members learned while preparing for tenure (promotion) that they wish they had learned beforehand; (5) opportunities in translational medicine and science; (6) ethics and moral courage in the academic workplace; and (7) managing and prioritizing time. The CMP provides the guest experts with a brief biography of each junior faculty member and a list of the members’ questions prior to the luncheon. The last luncheon of the academic year is attended only by the junior faculty members, one of whom chairs the meeting. While this meeting is largely a social event and an opportunity for junior faculty members in different divisions to become better acquainted, it is also used to gather suggestions for improving the CMP and to solicit topics for the following year’s luncheons.

OUTCOMES

Sixteen junior faculty members have joined the CMP since its inception in September 2006. Of these, 10 were on tenure track and 6 on clinical, fixed-term appointments. At the time this report was written, the CMP had 9 participants, 6 of whom were tenure track and 3 of whom were clinical appointments. The CMP had junior faculty members from all 5 divisions within the school, representing disciplines including the basic sciences, translational and clinical research, health outcomes research, and educational research. All of these faculty appointments place an emphasis on scholarship. To date, 13 of the 16 junior faculty members who have participated in the CMP either completed or remained in the CMP, 1 faculty member chose to temporarily suspend participation in the CMP, 1 faculty member elected to focus on clinical practice, and 1 junior faculty member accepted a new position elsewhere but remained an adjunct faculty member in the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. While most junior faculty members remained in the CMP until they submitted their dossiers for promotion, in several cases, faculty development was sufficient to warrant an earlier exit. The mentors outside the school have been primarily from the Schools of Medicine and Public Health and the Department of Chemistry and have included departmental chairs, administrators, and center directors.

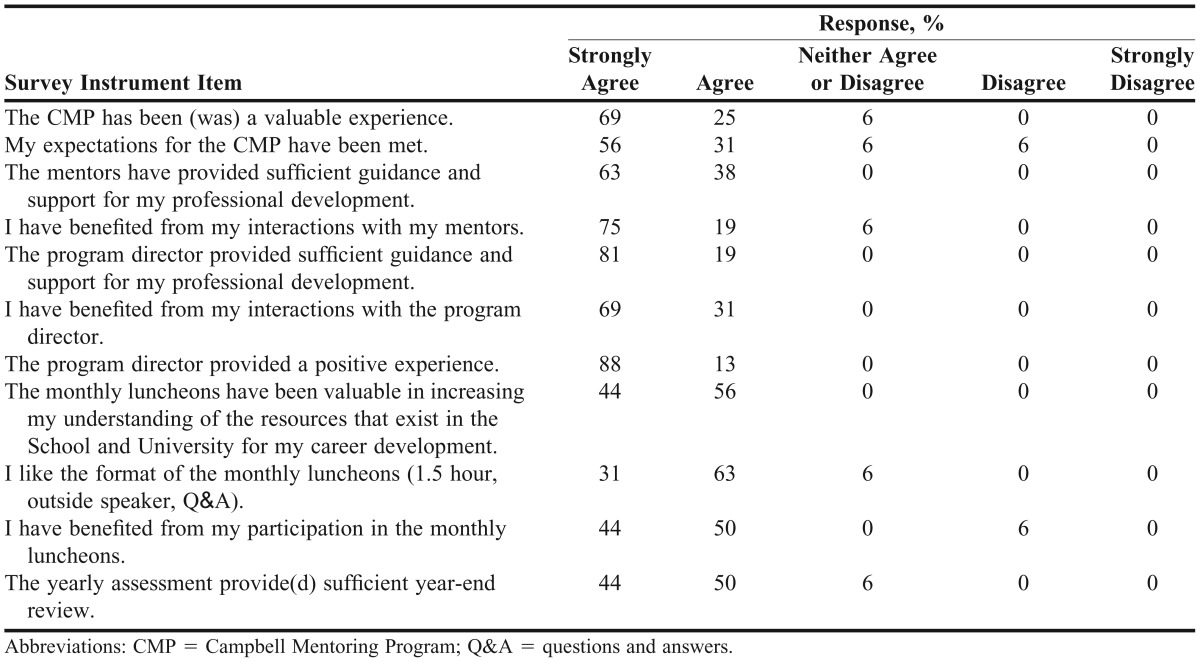

Although it was difficult to assess the CMP without a control study group, the program was reviewed at 3 and 6½ years. The last assessment included all 16 current and past participants (100% response rate) (Table 1). A 25-item survey instrument constructed by 1 of the CMP participants and the director included closed-ended and open-ended questions. The survey was administered by the School’s Office of Strategic Planning and Assessment by means of e-mail. Participation was voluntary and responses were anonymous. The survey instrument included both general and specific questions concerning junior faculty members’ participation in the CMP and their assessment of key operational components. The collated results were forwarded to the CMP director and the school leadership.

Table 1.

Junior Faculty Members’ Assessment and Overall Satisfaction with the Campbell Mentoring Program (n=16)

One of the survey instrument questions asked participants if the CMP had been (was) a valuable experience for them as junior faculty members. Of the 5 possible responses (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree), 11 strongly agreed (69%), 4 agreed (25%), and 1 (6%) neither agreed nor disagreed. Junior faculty members were asked what their expectations were upon joining the CMP (data not shown). The most frequent response indicated an expectation of guidance, support, and feedback for their scholarship and teaching efforts, while others expected enhanced opportunities to develop collaborations and interact with other junior faculty members. When asked whether their expectations for the CMP had been met, 9 junior faculty members strongly agreed (56%), 5 agreed (31%), 1 neither agreed nor disagreed (6%), and 1 disagreed (6%). The survey instrument provided the opportunity for participants to indicate which expectations were not met (data not shown). Of the few responses obtained, there was an expressed desire for increased interaction among the junior faculty members beyond those afforded by the monthly luncheons. In response to the question regarding which aspects of the CMP were most beneficial, interaction with the mentor(s) ranked highest (12 strongly agreed), followed by the interaction with the director (11 strongly agreed), and then the monthly luncheons (7 strongly agreed).

The survey instrument also inquired how frequently junior faculty members met with their mentors (data not shown). Although meetings within the CMP are voluntary, both junior faculty members and mentors were strongly encouraged to schedule biweekly meetings between individual junior faculty members and their mentors as well as monthly meetings of the entire team. The frequency of meetings reported was considerably lower than anticipated, with only 4 junior faculty members (25%) meeting with their respective mentoring team an average of once monthly and 8 junior faculty members (50%) meeting with their respective mentors bimonthly. When asked how frequently the entire team met, 4 teams reported meeting approximately bimonthly (25%), while the rest of the teams met less frequently or not at all. The survey instrument also inquired about the frequency and nature of help provided by the mentors (data not shown). In response to the question regarding whether mentors reviewed the junior faculty members’ scholarly efforts (eg, manuscripts, grants), 6 (38%) responded always, 2 (13%) most of the time, 7 (44%) sometimes, and 1 was never asked. When asked if the mentors assessed the junior faculty members’ teaching efforts (eg, attended lectures, viewed tapes, reviewed course material), 1 junior faculty member responded always, 2 (13%) sometimes, 2 (13%) never, and 11 (69%) said that they were never asked. In response to specific questions concerning the junior faculty-mentor interaction (data not shown), most participants felt that the mentors provided a big picture perspective of scholarship, teaching, and service (14 of 16, 88%), provided specific perspectives of scholarship, teaching, and service (13 of 16, 81%), provided strategies for applying for grant funding (11 of 16, 69%), helped in networking and identifying collaborators (13 of 16, 81%), provided insights into handling the stresses of an academic career (10 of 16, 63%), and provided insights into balancing work and personal life (8 of 16, 50%). Fewer participants found that their mentors helped with specific teaching activities (2 of 16, 13%).

When asked if the CMP director, monthly luncheons, and yearly assessment meetings provided a positive experience, all were viewed positively but to varying degrees. The supplementary comment field of the survey instrument also indicated that the director was instrumental in conveying to junior faculty members that the CMP had been designed for them and that the school cared about their experience and/or success. The survey concluded with a question regarding junior faculty members’ wish to continue in the CMP. Nine of 16 participants responded affirmatively without reservations, 1 responded negatively because of a career shift, and 6 had matriculated out of the CMP.

The assessment gained from individual and joint meetings closely parallelled the survey results. The CMP has provided a pathway by which junior faculty members could mature academically and expand the scope of their efforts, and by which their mentors could serve as role models for success, help to sharpen scholarship efforts and provide networking opportunities for the junior faculty members. These collective efforts have eased the junior faculty members entry into the university and their respective professional communities.

DISCUSSION

The CMP was designed to meet the unique circumstances of our environment and may not be appropriate for other colleges and schools of pharmacy. The school has a strong commitment to excellence in teaching, research, and service; is located in a comprehensive academic medical center; and is geographically proximate to one of the nation’s premier biomedical research centers (Research Triangle Park). How the school defines CMP “mentoring” (ie, with an emphasis on scholarship) is inextricably linked with our institutional “DNA.” A college or school of pharmacy in a different environment might define mentoring differently; there is no single definition or approach that would serve all of academic pharmacy.

There are several key elements necessary for a successful faculty mentoring program in academic pharmacy. There must be a clear understanding and agreement among faculty and administration about what mentoring is and is not. For some programs, it may be a role of moral advisor in the tradition of Oxford University. For others it may be a preventive-maintenance approach to help junior faculty members avoid pitfalls or mistakes, while for others, it may be a guide or translator function to help mentees navigate academic policies and procedures. The best definition is whatever best meets the needs of a given academic institution.

A supportive administration and dedicated core of mentors is absolutely essential to success. Administrative support can be demonstrated in financial terms (eg, stipends), release time, recognition for merit review, or other means, but it must be both significant and relevant. Mentors’ support begins with a personal commitment to help the next generation of faculty members succeed and to invest time, energy, and resources to that end. Most mentoring programs fail, in part, because the mentors were too passive in engaging junior faculty members. As Campbell wrote and repeatedly taught, “Mentoring is a contact sport.” Similarly, junior faculty members must be engaged in the mentoring process. Junior faculty members are often reluctant to “inconvenience” their senior counterparts, and in the beginning, may not even know what to request. Several factors likely contribute to this result. Accordingly, the CMP has recently made efforts to reduce cultural barriers of seniority and station through discussions involving both junior faculty members and their mentors. Regular, frequent, substantive interaction between mentors and junior faculty members, initiated by either party is essential. Equally important, junior faculty members must recognize that their mentors want to assist, which requires that they dismiss any preconceived notions that the mentors are there to be consulted only on an irregular basis and only for high-level, late-stage discussions. Consultation and problem solving are at the root of the scholarship process and require continued thought, best developed by the exchange and the refinement of ideas.

Any faculty mentoring program must have a single, visible locus, which, at our school, is the CMP director. The required time commitment of this position will vary depending on the program’s size and scope. In any circumstance, however, the director must embrace and implement the program’s mission and guidelines, nurture and monitor the junior faculty members, serve as a confidential and trusted advisor, maintain the integrity of the teams, and act as the program’s spokesperson. Most importantly, the director must be receptive to change.

CONCLUSIONS

The UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy has created a scholarship-intensive mentoring program for its junior faculty members. The Campbell Mentoring Program was designed to be uncomplicated, transparent, and accountable. Key to its success is the maintenance of an institutional climate wherein mentoring is considered a strength, junior faculty members engage the mentoring team, and junior faculty members, mentors, and the school’s leadership are committed to a defined mentoring plan. While the program is constantly evaluated and refined, it has achieved a record of faculty success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Dr. William Campbell, an exemplary educator and mentor and driving force of the CMP, as well as Dean Robert Blouin, who has been a strong supporter of faculty mentoring and has provided the author with the opportunity to direct the CMP. The author is grateful to the North Carolina Pharmacy Foundation and the State of North Carolina for their support, to junior faculty members and mentors who have participated in the CMP, and also to Dr. Lynn Dressler and Ms. Amy Sloane, whose expertise and help were instrumental in evaluating the CMP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell WH. Mentoring of junior faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1992;56(1):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullin J. Philosophical backgrounds for mentoring the pharmacy professional. Am J Pharm Educ. 1992;56(1):67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers RK. Faculty development. The nature and benefits of mentoring. Am J Pharm Educ. 1992;56(1):71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller K, Maniscalco-Feichtl M, Droege M. The role of the mentor in retaining junior pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 41. doi: 10.5688/aj720241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzger AH, Hardy YM, Jarvis C, et al. Essential elements for a pharmacy practice mentoring program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(2):Article 23. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeind CS, Zdanowicz M, MacDonald K. Developing a sustainable mentoring program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5):Article 100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wutoh AK, Colebrook MN, Holladay JW, et al. Faculty mentoring programs at schools/colleges of pharmacy in the U.S. J Pharm Teach. 2000;8(1):61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins EGC, Scott P. Everyone who makes it has a mentor. Harvard Bus Rev. 1978;56(4):89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roche GR. Much ado about mentors. Harvard Bus Rev. 1979;57(1):14–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy; Bill and Karen Campbell Faculty Mentoring Program. http://www.pharmacy.unc.edu/faculty/bill-and-karen-campbell-faculty-mentoring-program. Accessed January 31, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines ST. The mentor-protégé relationship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 82. [Google Scholar]