Abstract

Objective. To determine pharmacy students’ perceptions regarding cultural competence training, cross-cultural experiences during advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs), and perceived comfort levels with various cultural encounters.

Methods. Fourth-year pharmacy (P4) students were asked to complete a questionnaire at the end of their fourth APPE.

Results. Fifty-two of 124 respondents (31.9%) reported having 1 or more cultural competence events during their APPEs, the most common of which was caring for a patient with limited English proficiency.

Conclusion. Students reported high levels of comfort with specific types of cultural encounters (disabilities, sexuality, financial barriers, mental health), but reported to be less comfortable in other situations.

Keywords: cultural competence, assessment, advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE), cultural competence training

INTRODUCTION

The racial and ethnic composition of the United States population is rapidly changing and thus it is inevitable that pharmacists will interact with patients from a variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds.1-6 Improving health providers’ cultural competence is one strategy suggested for providing effective health care to culturally diverse patients, as well as for reducing health disparities and improving patient outcomes.2,7 Cultural competence as it applies to healthcare is described as “the ability to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviors, and to tailor care delivery to patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs.”8 This includes mental health needs, disabilities, and socioeconomic background.

Shaya and colleagues found that training in cultural competence is more effective if initiated in the early stages of the healthcare professional’s education.6 This idea is reflected in the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education’s 2007 guidelines, which state that colleges and schools of pharmacy must address cultural appreciation within the curriculum and ensure that pharmacy graduates are able to incorporate cultural diversity in their practice.9 However, the methods of providing cultural competence have not been standardized.4

The extent to which pharmacy schools have implemented cultural competence training and the methods they have used have varied. Although some studies have described the implementation of cultural activities during introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) and APPEs to improve cultural competence, most have described introducing cultural competence training in required and/or elective courses.2-4,10 While the methods of teaching differed, the majority of assessment strategies used pre- and post-intervention surveys to determine changes in students’ perceived level of competence. Similarly, other health professions students such as medical, dentistry, and physician assistant students have received cultural competence training within required clerkships, and classroom courses, with assessments primarily focused on improvement in knowledge level.11-14 Few of these studies describe students’ responses to the cultural events experienced.

In this study, students’ self-assessment of their application of cultural competence training during APPEs was explored. The primary objectives assessed if P4 students had an opportunity to apply cultural competence training during their first 4 APPE experiences, what types of cultural competence events they encountered, how they applied cultural competence knowledge, and their perceived level of comfort in providing culturally competent care to patients. Secondary objectives were to identify which characteristics (eg, demographics, education, training) were associated with P4 students’ perceived ability in providing culturally competent care, determine P4 students’ perceived adequacy of cultural competence training in the curriculum, and determine the need for further education or course material regarding cultural competence.

METHODS

Approximately 6 lecture hours were devoted to cultural competence in the Midwestern University Chicago College of Pharmacy curriculum, which followed a 10-week quarter system. The curriculum included two 2-hour lectures on cultural competence and health communications, respectively. As a part of the longitudinal IPPE, students were required to assess the cultural values and beliefs of 2 to 4 patients. An active-learning experience was provided with an opportunity for students to answer questions and discuss their culture during a small-group, 90-minute workshop associated with the IPPE course.

A 5-part student questionnaire was developed that included 54 questions and was designed to be completed in 10 minutes. In the first section of the survey instrument, students were asked to provide demographic information (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity, work experience). The second part consisted of Likert scale questions (1=none to 5=a lot) about students’ previous cultural competence training and additional questions about where they received their training and if they felt they needed further training. The third portion of the survey instrument consisted of free-response type questions that asked students to describe their cultural competence experiences and their responses to these experiences. Additionally, students were asked how comfortable they felt providing this care (1=not at all to 5=very).

The fourth part of the survey instrument addressed students’ level of comfort in a variety of cultural situations and encounters. This part of the questionnaire used the scale and several specific clinical encounters and situations from the Clinical Cultural Competence Questionnaire (CCCQ).15 The CCCQ was developed as a tool for assessing physicians’ provision of culturally competent health care to diverse patient populations. The instrument was validated in measuring pharmacy students’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and encounters in cultural environments at Xavier University of Louisiana College of Pharmacy.16 Students were asked to rate how comfortable they felt in these situations using a Likert-type scale similar to that used on the first section of the questionnaire (responses ranged from 1=not at all to 5=very). The last part of the survey instrument provided space for students to provide comments and suggestions. Participants were instructed to answer sections 2 through 5 of the questionnaire based on the following definition of cultural competence: “the ability to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors and to tailor care delivery to patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs. This includes mental health disorders, disabilities, sexual orientation and socioeconomic background.”8 A pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted for face validity using the college’s pharmacy residents as subjects. Approval for this study was obtained from the Midwestern University Institutional Review Board. Students’ participation was voluntary and completion of the survey was means for consent.

All P4 students were asked to complete the MWU Cultural Competence Questionnaire at the end of their fourth APPE block during a mandatory class meeting on campus. The survey instrument, an instruction sheet, and a return envelope were mailed to those students completing an APPE at a distant site.

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used to report all survey items. The chi-square test was performed to analyze which characteristics (eg, demographics) were associated with P4 students’ perceived ability in cultural competence.

RESULTS

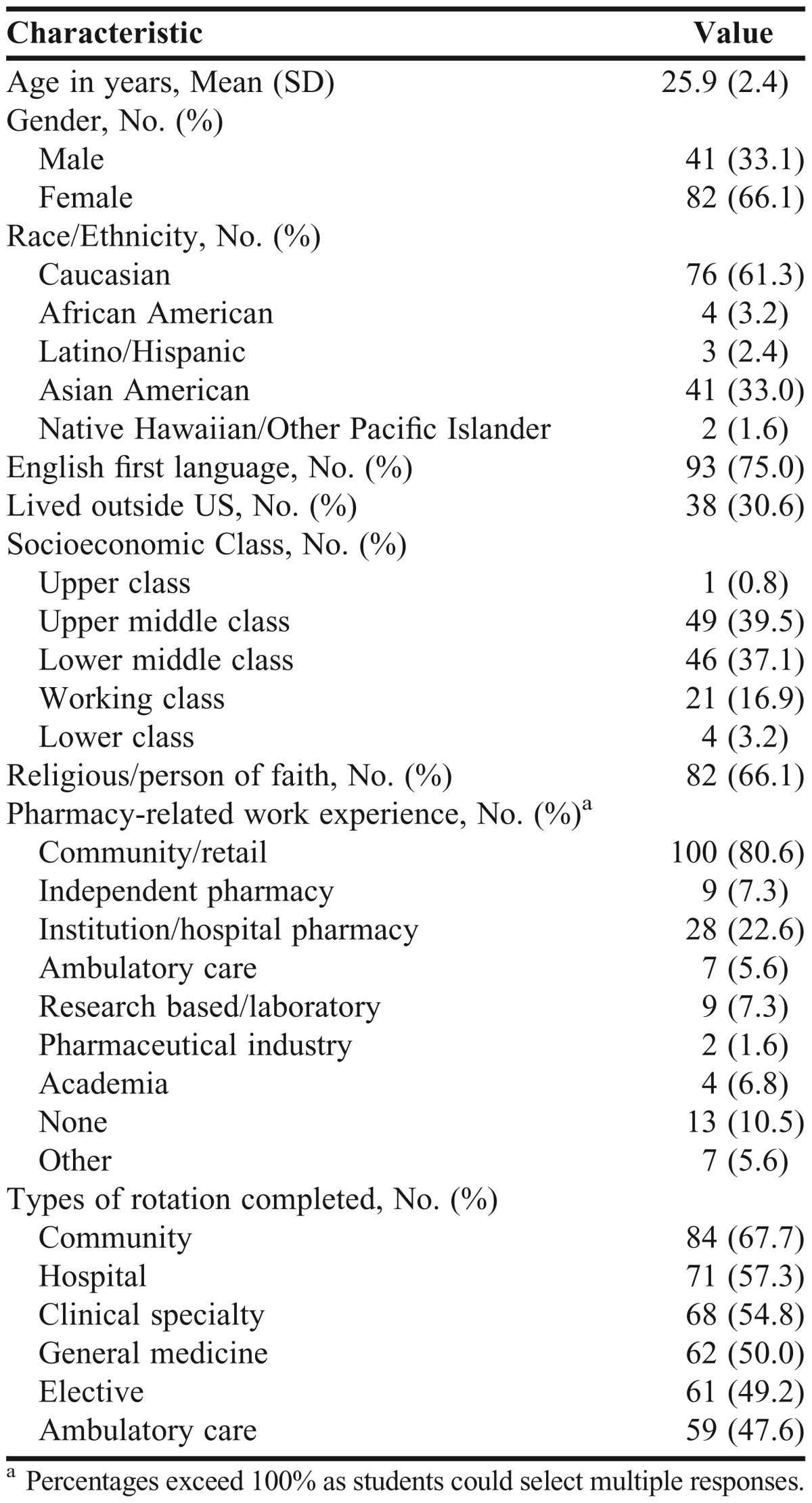

Of the 194 P4 students at MWU-CCP, 124 completed the survey instrument. The usable response rate of 76% was calculated by dividing the number of returned survey instruments that were completed (ie, some were returned but not completed) by the total number of survey instruments distributed. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 124 respondents. Most of the students received some form of cultural competence training while attending another institution, undergoing previous and/or current job training, and/or during the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum at MWU.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Fourth-year Pharmacy Students Who Completed a Survey Regarding Cultural Competence (n=124)

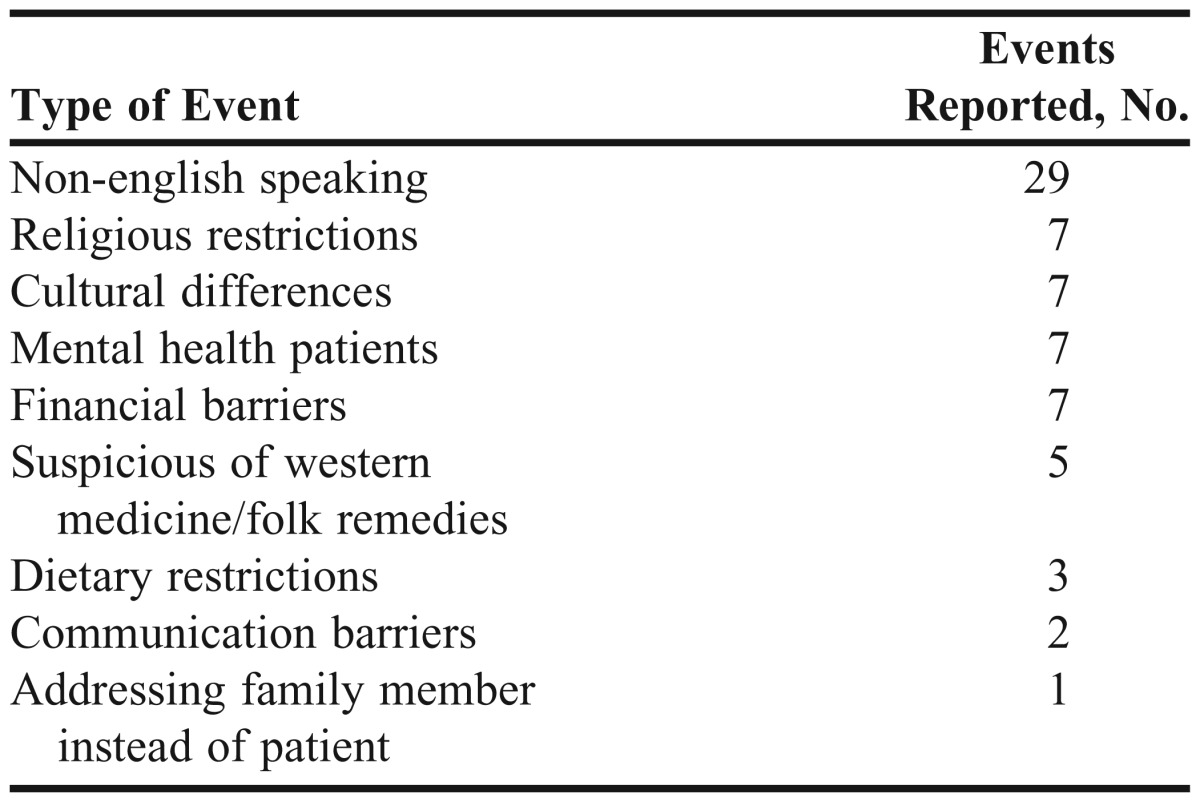

Fifty-two (31.9%) students reported that a cultural competence event(s) occurred during their APPEs. Sixty-eight cultural competence events were reported. Based on students’ descriptions, 9 types of cultural events were identified (Table 2). The most common type of cultural event was caring for a patient with limited English proficiency.

Table 2.

Cultural Events That Fourth-Year Pharmacy Students Reported Experiencing During Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (N=68)

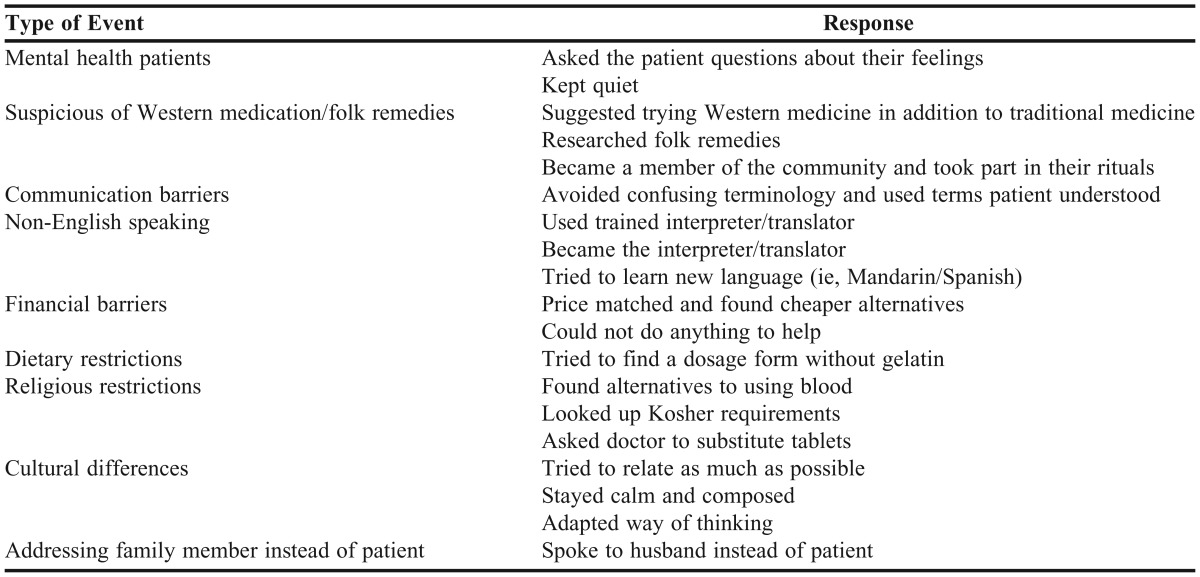

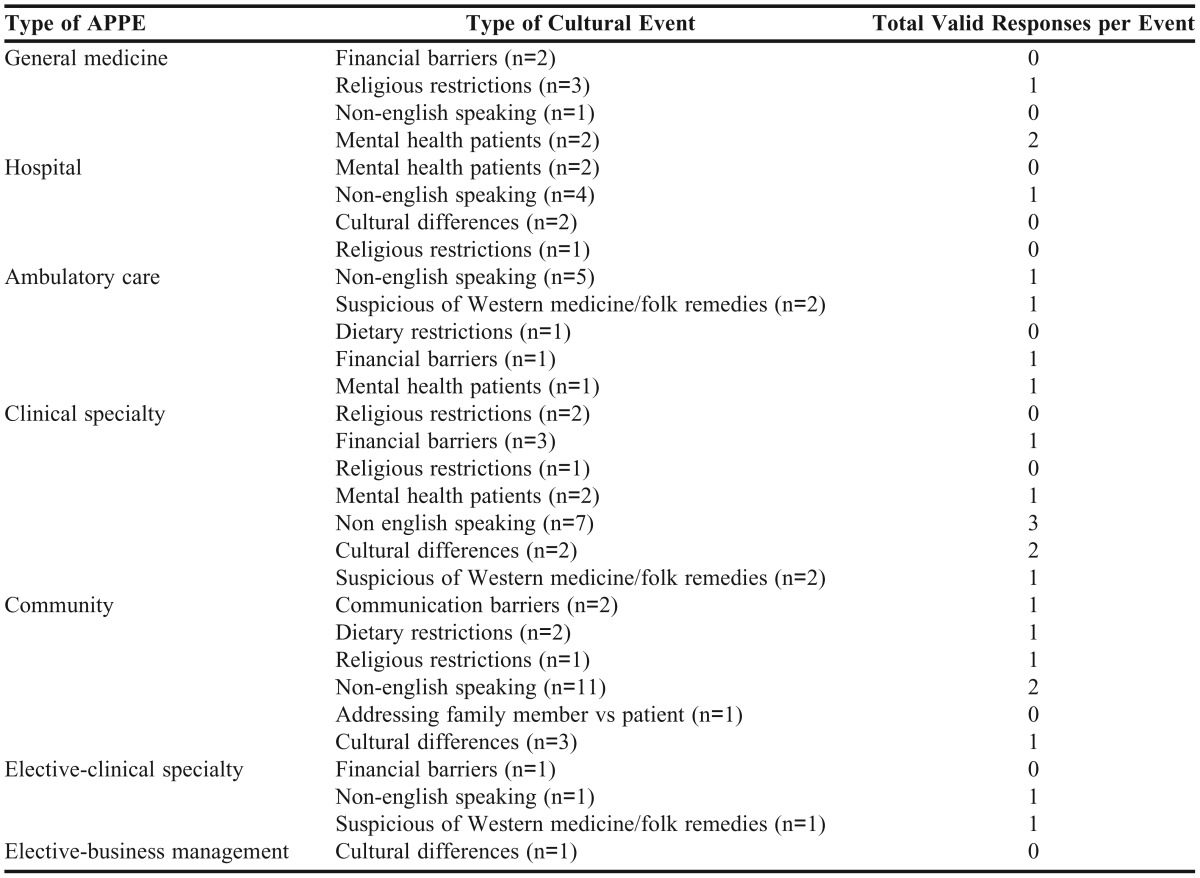

Table 3 presents selected students’ responses to cultural competence events. Responses to cultural encounters included using an interpreter for a patient with limited English proficiency, finding less expensive prescription medication alternatives for a patient with financial barriers, and looking up kosher requirements for a patient with religious restrictions regarding medications. Responses to cultural events were excluded if the student failed to describe a cultural event, and if the description of the event was not related to culture or was illogical. Table 4 shows the type of events encountered by type of APPE. For the majority of events reported, students did not provide valid responses.

Table 3.

Selected Fourth-Year Pharmacy Students’ Responses to Cultural Events

Table 4.

Cultural Events Experienced by Fourth-Year Pharmacy Students by Type of Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience They Were Completing

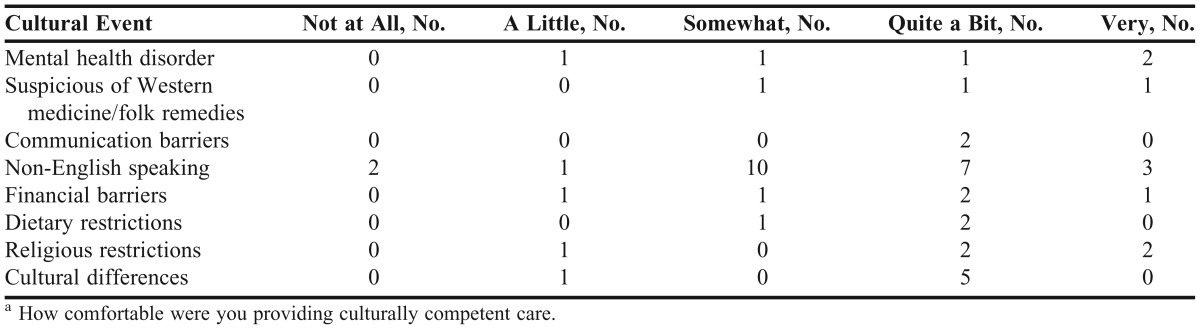

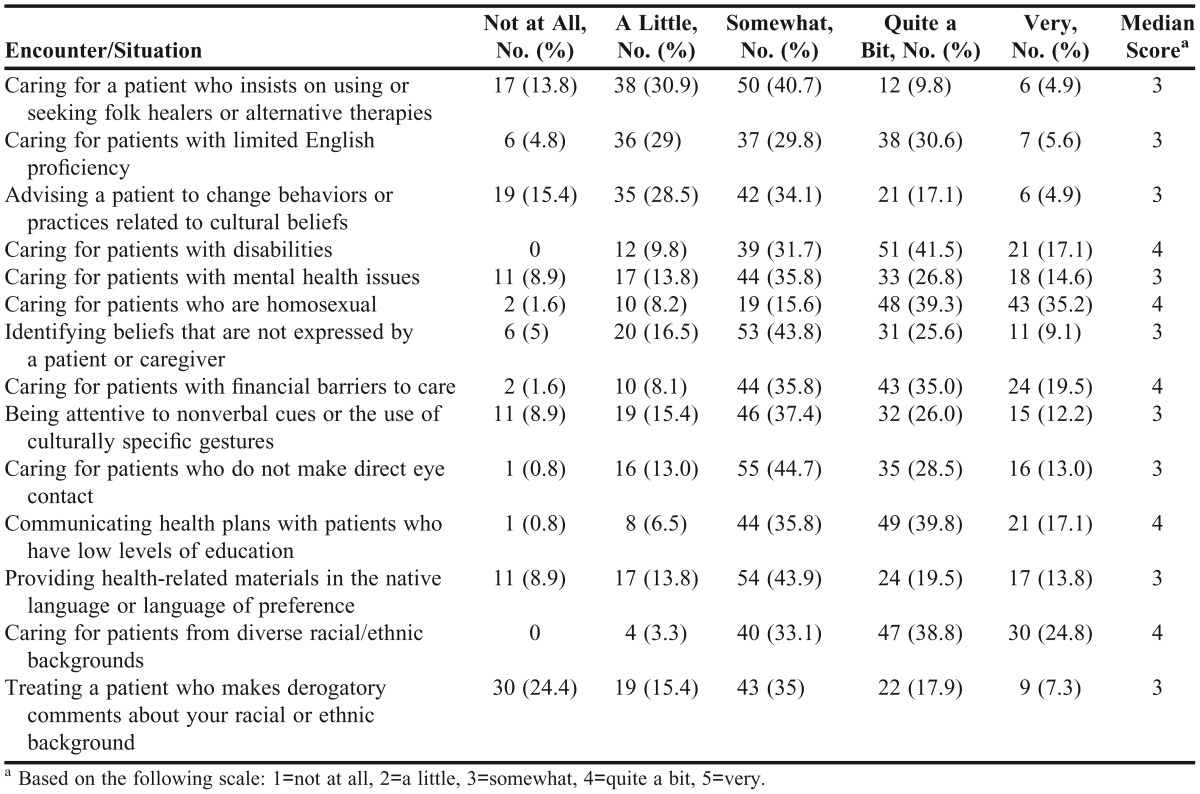

Of the 52 responses received regarding the student’s degree of comfort with providing culturally competent care, 60% were “quite a bit” (Table 5). When assessing students’ comfort level in specific cultural encounters or situations, students reported they were more comfortable: caring for a patient who was homosexual, caring for a patient from a different racial/ethnic background, caring for a patient with disabilities, and communicating health plans with a patient who had a low level of education (Table 6). Students reported being more uncomfortable when: caring for a patient who insisted on using or seeking folk healers or alternative therapies, advising a patient to change behaviors or practices related to cultural beliefs that impaired one’s health, and treating a patient who made derogatory comments about the student’s racial or ethnic background.

Table 5.

Fourth-Year Pharmacy Students’ Comfort Level with Reported Cultural Competence Events (N=47)a

Table 6.

Fourth-Year Pharmacy Students’ Comfort Level in Cultural Encounters and Situations (N=124)

Caucasian students were more comfortable than students of other races with caring for mental health patients (p=0.004). Those students who identified themselves as having a specific faith/religion were less comfortable than other students with patients with disabilities (p=0.020), patients who were homosexual (p=0.014), and patients who did not make eye contact (p=0.049), and were less likely to be attentive to nonverbal cues or culturally specific gestures (p=0.022).

More than half (67.5%) of respondents believed they had received sufficient cultural competence training; however, 47.2% believed the Midwestern University PharmD curriculum should contain more cultural competence training. The majority of the students (77.9%) did not believe cultural competence should be a standalone required course, while 71.3% believed it should be offered as an elective course.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to characterize the types of cultural events P4 students’ encounter during APPEs and their responses to those events. Thus, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with those of other studies as those studies focused on enhancing students’ self-perception, awareness, knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards cultural competence after classroom/experiential activities. Nonetheless, a majority of the students surveyed in this study perceived being at least somewhat comfortable with providing culturally competent care, which corresponds with their increased confidence in ability to provide culturally competent care after completing classroom-based courses and experiential learning activities.2

The majority of students did not provide valid explanations regarding the quality and nature of the cultural encounters they reported. This leaves in question how comfortable students really are providing culturally competent care and how accurate their perceptions of their comfort level really are. One possible approach to addressing this concern is to incorporate activities in the curriculum that require preceptor observation and feedback. Paul and colleagues describe cultural activities in which preceptors provide immediate feedback to medical students after students practiced incorporating cultural competence during patient encounters and this led to significantly higher levels of competence observed role modeling.14 Further research in this area is necessary.

The results cannot be generalized to other colleges and schools of pharmacy as only perceptions of Midwestern University P4 students were obtained. These results were self-reported by students; thus, answers may have been exaggerated or students may have forgotten pertinent details. The questionnaire did not ask students to describe the geographic location or community setting in which the APPE took place, and this could have affected the type and amount of cultural encounters the student experienced. Students also were not evaluated by preceptors during the reported cultural encounters, and thus may not have been as comfortable as they perceived. Some students may have had limited patient interaction by the fourth APPE block when the survey was conducted. Likewise, some students could have had 2 APPE blocks off or have been on APPEs that involved minimal patient interaction or care. The questionnaire was administered before an examination and answers on the survey may have been inherently biased by the students’ feelings (eg, lack of focus or interest) at the time they completed the survey instrument. This study was unable to directly correlate students’ perception and skills, comfort level, or competence to training received at MWU-CCP. Students may have applied cultural training received at other institutions or at previous or current jobs.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study contributes to the literature on cultural competence among pharmacy students. By characterizing cultural events experienced on APPEs and describing the responses to events, colleges and schools of pharmacy have an idea of the types of cultural events pharmacy students are encountering on APPEs. These events can thus be addressed within the pharmacy curriculum to enhance students’ cultural competence. The responses can be used to identify areas in which students might benefit from more extensive training or reinforcement of previous training, and to identify gaps in training. This study supports the need to address a variety of cultural experiences within the pharmacy curriculum, and the importance of ensuring pharmacy students are adequately trained to provide culturally competent care.

This study has several possible implications. Our college could revise the curriculum to include training in cultural competence areas with which students were not comfortable. Additionally, students could be surveyed at the end of the P4 year instead of after the fourth APPE as students may have had more and a variety of cultural encounters by that time. There is an opportunity to further the study by assessing the application or student responses to cultural events at colleges and schools of pharmacy across the country. Studies are needed to identify potential barriers to implementation of cultural competence training.

CONCLUSION

The most common type of cultural event that P4 students reported encountering was caring for patients with limited English proficiency. Students reported high levels of comfort with specific types of cultural encounters (disabilities, sexuality, financial barriers, mental health), but responses suggest there is room for improvement in preparing students to be comfortable in other cultural situations (patients seeking alternative therapies, nonverbal cues, no eye contact).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors were supported by the Midwestern University Center for Teaching Excellence Grant. The authors thank Dr. Thomas Reutzel, PhD, for his assistance with the statistical analysis of the questionnaire; Michael Chindalah, PharmD candidate, and Yousra Abuasi, PharmD candidate, for their assistance with data entry; and Dr. Andrew Traynor, PharmD, for editing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Census Bureau. Population Profile of the United States. National Population Projections. An older and more diverse nation by midcentury. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html. Accessed on August 31, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muzumdar JM, Holiday-Goodman M, Black C, Powers M. Cultural competence knowledge and confidence after classroom activities. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8):Article 150. doi: 10.5688/aj7408150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirier TI, Butler LM, Devraj R, et al. A cultural competence course for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Edu. 2009;73(5):Article 81. doi: 10.5688/aj730581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assemi M, Cullander C, Hudmon KS. Implementation and evaluation of cultural competence training for pharmacy students. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(5):781–786. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vyas D, Caligiuri FJ. Reinforcing cultural competence concepts during introductory pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):Article 129. doi: 10.5688/aj7407129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaya FT, Gbarayor CM. The case for cultural competence in health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(6):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/aj7006124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyoni EM, Ives TJ. Assessing the implementation of cultural competence content in the curricula of colleges of pharmacy in the United States and Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):Article 24. doi: 10.5688/aj710224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diggs AK, Berger BA. Cultural competence. In: Berger BA. Communication Skills for Pharmacists. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2009:199. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/S2007Guidelines2.0_ChangesIdentifiedInRed.pdf. Accessed on August 31, 2011.

- 10.Haack S. Engaging pharmacy students with diverse patient populations to improve cultural competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/aj7205124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck B, Scheel MH, De Oliveira K, Hopp J. Integrating cultural competency throughout a first-year physician assistant curriculum steadily improves cultural awareness. J Physician Assist Educ. 2013;24(2):28–31. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201324020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunderson D, Bhagavatula P, Pruszynski JE, Okunseri C. Dental students’ perceptions of self-efficacy and cultural competence with school-based programs. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(9):1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genao I, Bussey-Jones J, St. George DM, Corbie-Smith G. Empowering students with cultural competence knowledge: randomized controlled trial of a cultural competence curriculum for third-year medical students. J Nat Med Assoc. 2012;101(12):1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul CR, Devries J, Fliegel J, Van Cleave J, Kish J. Evaluation of a culturally effective health care curriculum integrated into a core pediatric clerkship. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(3):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Like RC. Clinical Cultural Competence Questionnaire (CCCQ). Center for Healthy Families and Cultural Diversity, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Aetna Foundation-Funded Cultural Competence/Quality Improvement Study, http://rwjms.umdnj.edu/departments_institutes/family_medicine/chfcd/index.htm. Accessed August 31 2011.

- 16.Echeverri M, Brookover C, Kennedy K. Nine constructs of cultural competence for curriculum development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article 181. doi: 10.5688/aj7410181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]