Abstract

Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are the key effector cells executing physiologic tissue repair leading to regeneration on one hand, and pathological fibrogenesis leading to chronic fibrosing conditions on the other. Recent studies identify the multifunctional transcription factor Early Growth Response-1(Egr-1) as an important mediator of fibroblast activation triggered by diverse stimuli. Egr-1 has potent stimulatory effects on fibrotic gene expression, and aberrant Egr-1 expression or function is associated with animal models of fibrosis and human fibrotic disorders including emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and systemic sclerosis. Pharmacological suppression or genetic targeting of Egr-1 blocks fibrotic responses in vitro and ameliorates experimental fibrosis in the skin and lung. In contrast, Egr-1 appear to acts as a negative regulator of hepatic fibrosis in mouse models, suggesting a context-dependent role in fibrosis. The Egr-1-binding protein Nab2 is an endogenous inhibitor of Egr-1-mediated signaling, and abrogates the stimulation of fibrotic responses induced by transforming growth factor-ß (TGF-ß). Moreover, mice deficient in Nab2 show excessive collagen accumulation in the skin. These observations highlight a previously unsuspected fundamental physiologic function for the Egr-1/Nab2 signaling axis in regulating fibrogenesis, and suggest that Egr-1 may be a potential novel therapeutic target in human diseases complicated by fibrosis. This review summarizes recent advances in understanding the regulation and complex functional role of Egr-1 and its related proteins and inhibitors in pathological fibrosis.

Keywords: Egr-1, Nab2, TGF-ß, fibrosis, scleroderma, fibroblast, myofibroblast, p300, c-Abl

Introduction

Fibrosis contributes to the pathogenesis of diverse conditions, has no effective therapy to date, and represents a major global health problem[1]. Pathological fibrosis is characterized by excessive production and tissue accumulation of collagens and other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, resulting in aberrant biochemical and biomechanical reorganization of connective tissue in affected organs. Persistent or recurrent chemical, infectious, mechanical or autoimmune injury in a genetically predisposed individual causes prolonged activation of fibroblasts, the key effectors in fibrosis [2]. While a plethora of extracellular signals are known to induce fibroblast activation, the TGF-ß signaling axis appears to represent the core pathway for virtually all forms of fibrosis [3]. In mesenchymal cells, TGF-ß signals to target genes are conveyed through both canonical Smad-dependent, and non-canonical (Smad-independent) pathways [4]. It was recently shown that one of the targets of TGF-ß is the transcription of the zinc-finger DNA-binding protein early growth response-1 (Egr-1), a member of a transcription factor family, that appears to play a central role in orchestrating fibrotic responses. This review highlights recent insights into the expression, complex function and therapeutic potential of Egr-1 proteins and their negative regulators in the context of pathological fibrosis.

Egr-1 structure, function and regulation

Discovered some two decades ago, the Egr-1 gene (also named as NGF1A and krox-24) encodes an 80 kDa DNA-binding transcription factor [5]. Egr-1 is the prototypic member of a zinc-finger transcription factor family that also includes Egr-2, Egr-3 and Egr-4. These four proteins have high degree of homology at their DNA-binding zinc finger domains, but they have divergent sequences outside the DNA-binding domains. All four Egr proteins bind to a 9-bp GC-rich DNA sequence called ERE that is found in multiple target gene promoters [6]. Two non-DNA-binding proteins called Nab1 and Nab2 are closely related to Egr-1 and play important roles in negative regulation of Egr-1 activity by preventing excessive Egr-1 signaling. In normal tissues, Egr-1 expression is generally low or undetectable. However, Egr-1 expression is elevated at sites of injury. Diverse injury-associated signals are potent inducers of Egr-1 expression The Egr-1 protein has several identified modular domains comprised of the zinc-finger DNA-binding domain (with a nuclear localization sequence), a transactivation domain and the Nab protein interaction domain (R1), as well as a nuclear localization sequence [7,8]. Binding of Nab1 and Nab2 to the R1 inhibitory domain in Egr-1 causes recruitment of the nucleosomal remodeling and deacetylation (NuRD) complex containing histone deacetylases HDAC1/2, resulting in repression of Egr-1 transcriptional activity [9]. Expression of Nab2 is regulated by Egr-1, and so induction of Egr-1 is normally followed by Nab2-mediated repression of its activity. In this way, endogenous Nab2 enables Egr-1 to tightly control its own biological activity to prevent excessive transactivation of target gene expression [10]. Biological activities linked to Egr-1 and related family proteins are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biological activities linked to Egr-1 and related Egr family proteins.

| Gene | Prominent Functions | Mouse Knockout phenotype | Disease associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egr-1 | Growth, development, differentiation, apoptosis; implicated in cancer, inflammation, fibrosis | Homozygous Egr-1 null overtly healthy; reduced body size; reduced fertility in females; impaired liver regeneration | Prostate cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, schizophrenia, SSc |

| Egr-2 | Peripheral nerve myelination, hindbrain development, T cell regulation, apoptosis; immune tolerance | Congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy; perinatal death | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Dejerine-Sottas syndrome, congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy: schizophrenia; SLE, SSc |

| Egr-3 | Sympathetic nervous system development, T-cell activation, survival and proliferation | Ataxia; lack of muscle spindle | Schizophrenia |

| Egr-4 | Central nervous system function (incompletely understood) | Homozygous Egr-4 null overtly healthy; males infertile | Unknown |

| Nab1* | Peripheral nerve differentiation, cardiac hypertrophy | Nab1-null mice overtly healthy. | Unknown |

| Nab2* | Vascular homeostasis, endothelial cell, fibroblast differentiation; inflammation, peripheral nerve myelination | Nab2 null overtly healthy; thick dermis; increased dermal ccollagen accumulation | Unknown |

Nab1/Nab2 double null mice have severe hypomyelination and suffer early lethality, scleroderma; SSc, systemic sclerosis; SLE Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms

The factors shown to induce Egr-1 expression (Table 2) include many that are associated with tissue injury [11-18]. The human Egr-1 gene promoter harbors five consensus serum response elements (SREs) that are recognized by serum response factor and the ternary complex factors Elk-1 and related Ets family oncogenes [19]. Induction of Egr-1 is mediated through the ERK kinase cascade converging on Elk-1, an Ets-family DNA-binding transcription factor [20], [11,21]. Recent studies indicate that in addition to the ERK cascade, Egr-1 expression can also be induced by growth factors acting through the Rho-ROCK pathways modulating cytoskeletal actin dynamics [22]. Beyond its rapid and robust induction at the transcriptional level, Egr-1 activity can also be regulated by post-translational modifications [23,24]. One prominent pathway for Egr-1 modification is acetylation, which generally leads to diminished Egr-1 activity by negative feedback loops [25]. On the other hand, Egr-1 activity is positively regulated by its phosphorylation [25,26] and sumoylation [27,28]. The nature of post-translational modifications targeting the Egr-1 protein influences both the choice of its target genes as well as its transcriptional activity.

Table 2. Extracellular signals that regulate Egr-1 expression.

| Extracellular signals | Egr-1 expression |

|---|---|

| PDGF, TGF-ß, hypoxia, HGF, lipopolysaccharide (TLR4 ligand), oxidative stress, ischemia-reperfusion, cigarette smoke, ultraviolet light, mechanical stretch, thrombin, T cell receptor ligation, LPA | Up |

| PPAR-gamma Carbon monoxide |

Down Down (via PPAR-gamma) |

Egr-1 is a multi-functional transcription factor

Egr-1 is an exceptionally multi-functional transcription factor. In response to growth factor and cytokine signaling, Egr-1 regulates cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Consistent with its pleotropic function, aberrant Egr-1 expression is linked to human diseases, such as ischemic injury, cancers, inflammation, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular pathogenesis, in addition to fibrosis [12,29-34]. The role of Egr-1 in cancer pathogenesis is complex, as it seems to have both tumor suppressor and tumor-promoting effects [27,35-37]. While various agents including curcumin appear to down-regulate Egr-1 expression and have been evaluated in preclinical studies, it remains unclear if suppressing Egr-1 is desirable or potentially harmful in cancer.

Two different strains of mice with deletion of Egr-1 have been generated [38,39]. In light of its broad biological roles, it was a surprise that Egr-1-deficient mice viable and initially appeared to have a rather mild phenotype, predominantly female due to loss of lutenizing hormone production [38], or reduced body size [39]. Subsequent studies however showed the Egr-1-deficient mice had impaired liver regeneration [40], and altered tissue remodeling [34,41-43].

Egr-1 plays a central role in regulation of fibrogenesis

Recent studies indicate that Egr-1 is regulated by multiple fibrogenic signals, and that it has an important role in fibrosis [44]. We demonstrated that TGF-ß is a potent stimulus for Egr-1 expression in normal human fibroblasts [33]. In these cells, TGF-ß induces Egr-1 transcription in a Smad-independent manner by activating the MEK1/2/Erk signaling cascade converging on Elk-1. Moreover, ectopic Egr-1 expression in fibroblasts is sufficient to drive collagen gene transcription, suggesting that Egr-1 might be mediating the profibrotic stimulatory response elicited by TGF-ß [45]. Other studies showed that IL-13 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5), which are implicated in pulmonary fibrosis, can similarly stimulate Egr-1 expression via the MAPK signaling pathway [46].

The genes regulated by Egr-1(Table 3) include many that are associated with wound healing, tissue remodeling and fibrosis. The expression of these genes is regulated by Egr-1 through both direct and indirect mechanisms [20,21,46-50]. Moreover, Egr-1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a cellular transformation thought to be important in certain forms of fibrosis [50]. Induction of EMT by Egr-1 involves up-regulation of the transcription factor Snail, a master regulator of EMT that represses E-cadherin. Importantly, Egr-1 directly stimulates collagen gene expression. Ectopic expression of Egr-1 in skin and lung fibroblasts was accompanied by enhanced COL1A2 transcription and Egr-1 binding to conserved cognate DNA recognition sites within the collagen gene promoters [45]. Moreover, in the presence of stimulatory TGF-ß, Egr-1 caused a further stimulation of collagen transcription. In contrast, in fibroblasts lacking Egr-1, TGF-ß failed to elicit a maximal stimulatory effect despite an intact Smad signaling axis, indicating an indispensable role for Egr-1 in the fibrotic response [45]. Mutation analysis and ChIP assays further confirmed that the stimulation of collagen gene transcription by Egr-1 involved its direct binding to cognate regulatory elements in the collagen gene promoters [45].

Table 3. Genes regulated by Egr-1.

| Selected Egr-1 targets | TGF-β, PDGF, CTGF, PAI-1, fibronectin, FGF, HGF, VEGF, IGF2, CTGF, VCAN, Rad, ID4, EF-1α, EGFR, EZH2, TECK, DARC, TIMP1 |

| Target genes related to fibrogenesis | TGF-β, CTGF, IGFBP5, PDGF, GDF6, periostin, collagens, fibronectin, PAI-1, TIMP3, COMP, BGN, PLOD2, NOX4 |

In a mouse model of scleroderma induced by subcutaneous injections of bleomycin, onset of dermal fibrosis was accompanied by increased Egr-1 accumulation in lesional fibroblasts [33]. Conversely, the extent of fibrosis in the bleomycin model was attenuated in Egr-1-null mice [34]. Elias and coworkers showed that lung fibrosis elicited by transgenic overexpression of TGF-ß was similarly attenuated in Egr-1-deficient mice [41]. In mice with bleomycin-induced scleroderma, the PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone was shown to prevent the development of skin fibrosis [51]. Interestingly, substantial decrease in Egr-1 levels was observed in the lesional skin following rosiglitazone treatment, implicating Egr-1 as a potential target for the anti-fibrotic effects of PPAR-γ [51]. A recent study of a novel endostatin-derived peptide called E4 with potent anti-fibrotic activity indicated that amelioration of fibrosis in E4 peptide-treated mice was accompanied by a substantial reduction in Egr-1 levels in the fibrotic skin [52].

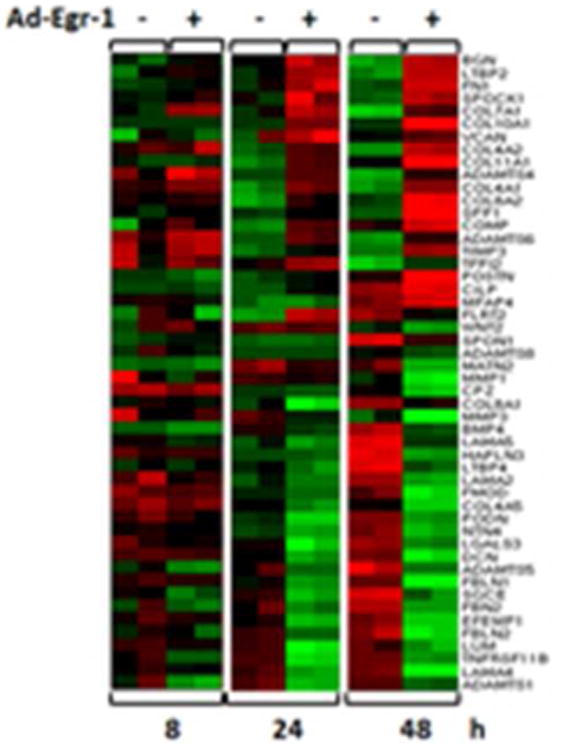

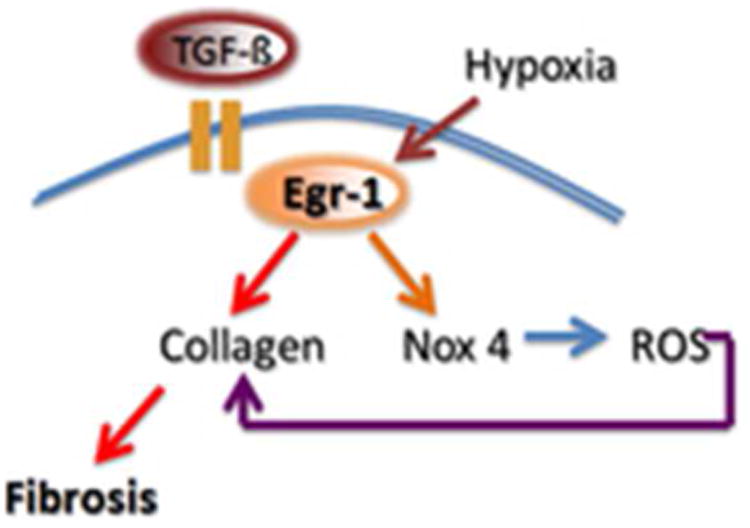

To better understand the effect of Egr-1 on fibroblast function, we performed genome-wide profiling of fibrosis-related transcripts induced by Egr-1 in normal fibroblasts. Microarray analysis identified 647 Egr-1-regulated genes that comprise the “fibroblast Egr-1 response gene signature” [53]. The signature includes a substantial number of genes associated with cell proliferation, TGF-ß signaling, wound healing, ECM, and vascular development. For instance, the expression of genes encoding multiple collagens, COMP, and periostin were all markedly increased by Egr-1 (Fig. 1). One of the genes most up-regulated by Egr-1 encodes the enzyme NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) [53], which catalyzes the generation of superoxides and ROS (data not shown). This Egr-1 target is particularly intriguing, since ROS and oxidative stress promote fibroblasts activation and are known to be implicated in fibrogenesis and SSc [54]. Since in SSc both chronic tissue hypoxia and enhanced TGF-ß activity are prominent, these two stimuli are likely to converge at Egr-1 to stimulate NOX4 expression with sustained ROS generation and chronic fibroblast activation (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Transcriptional responses induced by Egr-1 in fibroblasts.

Human dermal fibroblasts were infected with Ad-EGFP or Ad-Egr-1 for up to 48 h. Total RNA was subjected to genome-wide transcriptional analysis using human Illumina Microarray chips. Heatmap of differentially expressed genes related to extracellular matrix remodeling (FDR=0.01, >2- fold-change). The color represents the change of gene expression compared to control (red = increased, green = decreased).

Figure 2. Egr-1 regulates oxidative stress.

Tissue hypoxia and TGF-ß converge on Egr-1 to stimulate NOX4 expression with reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. ROS contribute to persistent fibroblasts activation and collagen production.

Unraveling profibrotic Egr-1 signaling: the roles of c-Abl and p300

Recent studies provide novel insights into the mechanistic basis for the profibrotic effects of Egr-1 by identifying the non-receptor tyrosine kinase c-Abl as an important upstream regulator, and the histone acetyltransferase p300 as an important downstream target, of Egr-1 in fibroblasts. We and others showed that TGF-ß activated c-Abl, with stimulation restricted to mesenchymal cells, that was not seen in epithelial cells [55,56]. Aberrant c-Abl activation is implicated in fibrogenesis, and pharmacological blockade of c-Abl in vivo or in vitro abrogated profibrotic TGF-ß responses and prevented fibrosis in animal models [56-59]. Imatinib mesylate is currently approved for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and is widely used for therapy. In a series of experiments with explanted fibroblasts, we demonstrated that Egr-1 was a downstream target of c-Abl [55]. Lesional skin fibroblasts in mice with bleomycin-induced fibrosis of skin displayed evidence of c-Abl activation in situ, and elevated phospho-c-Abl correlated with increased local expression of Egr-1. These studies position Egr-1 downstream of c-Abl in the fibrotic response, delineate a novel Egr-1-dependent intracellular signaling mechanism that underlies the involvement of c-Abl in fibrotic TGF-ß responses. Thus, Egr-1 may be a relevant profibrotic target gene inhibited by imatinib mesylate inhibition of c-Abl.

The dual-function phosphoprotein p300/CBP serves as both transcriptional coactivator and histone acetyl transferase, and is implicated in TGF-ß signaling [60]. In some cell types including fibroblasts, the cellular abundance of p300 is a critical factor in setting the intensity of TGF-ß responses [60-62]. In recent studies, we found that Egr-1 stimulated the expression of p300 and target gene-associated histone acetylation in TGF-ß-treated fibroblasts (Ghosh A. K. et al, unpublished). Moreover, in contrast to wildtype mice, in Egr-1-null mice TGF-ß was unable to induce p300 expression, establishing a key role for Egr-1 in the regulation of p300 expression and consequent chromatin modification events. In complementary studies, Yu et al established the importance of Egr-1 in regulating p300 expression and activity in prostate cancer [25].

Together, these studies place c-Abl upstream of Egr-1 and p300 in the TGF-ß signaling cascade regulating fibrogenesis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Intracellular signaling axis underlying profibrotic TGF-ß responses.

In fibroblasts, TGF-ß binding to its receptors causes Smad2/3 activation, recruitment of transcriptional coactivator p300 and enhanced collagen gene transcription. However, TGF-ß also activates a non-Smad pathway via c-Abl, which stimulates Egr-1. Egr-1 in turn induces p300 which catalyzes histone acetylation and chromatin unwinding, facilitating collagen transcription.

Egr-2 has profibrotic activities

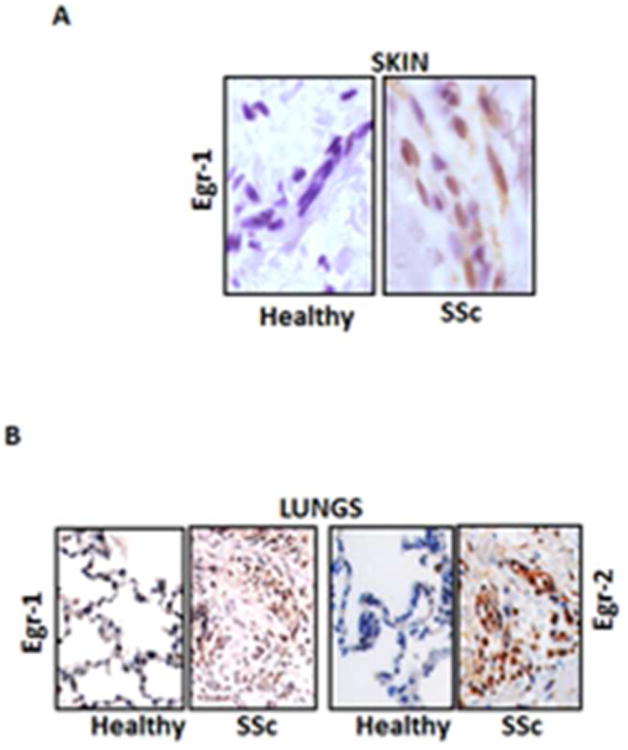

Egr-2 is highly homologous to and is regulated by Egr-1, and displays similar but not identical pattern of expression and regulation. In contrast to Egr-1 however Egr-2 has been primarily studied for its role in immune tolerance and neural development [63]. Egr-2 inhibits T cell activation and its deletion results in expansion of autoreactive T cells and loss of self-tolerance [64]. Mice with spontaneous lupus-like disease show diminished Egr-2 expression [65]. In striking contrast to the modest phenotype of Egr-1-null mouse, loss of Egr-2 is associated with early lethality. Egr-2 is also essential for hindbrain development and peripheral nerve myelination [63,66]. We recently undertook an investigation of Egr-2 regulation and function in the context of fibrogenesis. Our results revealed that TGF-β stimulated the expression of Egr-2 in normal fibroblasts. In contrast to Egr-1, which showed rapid up-regulation in response to TGF-ß, stimulation of Egr-2 was delayed but sustained [67]. Interestingly, Egr-1 itself induced Egr-2 expression. Significantly, we observed elevated Egr-2 levels in fibrotic skin and lung biopsies from patients with SSc (Figs. 4A and B). When expressed in normal fibroblasts, ectopic Egr-2 directly stimulated the expression of collagen genes. Subsequent genome-wide transcriptomic studies indicated that Egr-2 stimulated multiple genes related to fibrosis and tissue remodeling [67]. One of the most up-regulated genes in Egr-2-expressing fibroblasts encodes Type III collagen, a fibrillar collagen that is highly up-regulated in the lesional skin in SSc [68,69]. Interestingly, the “fibroblast Egr-2-regulated gene signature” showed only a modest overlap with the cohort of genes induced by Egr-1 in these cells, highlighting functional differences between these two structurally related transcription factors. While Egr-1 and Egr-2 appear to signal in an intricately linked network, the relative roles, cross-regulation and complementary vs. redundant functions in fibrogenesis and pathological fibrosis will require further investigation.

Figure 4. Elevated Egr-1 and Egr-2 in SSc skin and lungs.

A. Immunhistochemistry. Lesional skin tissues from SSc patients and the healthy controls. Original magnification, ×400. B. Lung tissues from patients with SSc-associated pulmonary fibrosis undergoing lung transplantation and normal donor lungs. Original magnification ×100.

NGFI-1A-binding protein 2 (Nab2) is an endogenous inhibitor of Egr-1

Nab proteins (Nab1 and Nab2) are delayed early-response genes that are structurally related to Egrs but negatively regulate their transcriptional activity. Nab2, a 55 kD nuclear protein, was originally identified in a yeast two-hybrid assay based on its ability to interact with, and inhibit the transcriptional activity of Egr-1[70]. In contrast to Egr-1 and Egr-2, Nab2 lacks DNA-binding activity but instead binds to the Egr-1 repression domain (R1), resulting in negative regulation of transcriptional responses [70]. Many of the same environmental stimuli for Egr-1, also induce Nab2 expression, but with delayed induction relative to Egr-1. In contrast to Nab2 is an inducible modulator of transcription, Nab1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues, and functions as a general transcriptional regulator [71]. Surprisingly given its important function in negatively regulating Egr activity, little is known about how the biological roles of Nab proteins function to modulate Egr target gene regulation. Mice with targeted deletion of Nab2 show no obvious phenotype, whereas mice lacking both Nab1 and Nab2 suffer from hypomyelination and early lethality [72]. Some studies have implicated Nab proteins in peripheral neuropathy, macrophage development, cardiac hypertrophy, and prostate cancer, but until recently the involvement and role of Nab2 in fibrosis was unknown [72-75].

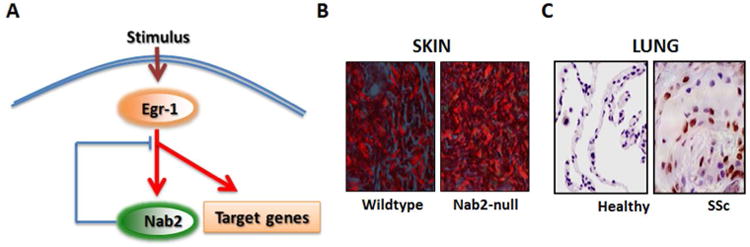

Negative feedback regulation of fibroblast activity maintained by Nab2

We investigated the regulation and function of Nab2 in normal human skin fibroblasts [76]. TGF-ß induced a striking up-regulation of Nab2. Time-course studies indicated that compared to Egr-1, induction of Nab2 by TGF-ß was delayed, but persisted even after 24 h in skin and lung fibroblasts. Nab2 overexpression in these cells not only blocked Egr-1 transcriptional activity, but also prevented the stimulation of collagen synthesis and myofibroblasts differentiation induced by TGF-ß [76] (Fig. 5A). The anti-fibrotic effects of Nab2 involved the histone deacetylase HDAC1, which was recruited to the COL1A2 promoter, resulting in reduced histone H4 acetylation at this locus. Moreover, in fibroblasts transfected with a dominant-negative CHD4, which disrupts normal NuRD function, Nab2 was no longer able to block fibrotic TGF-ß responses, confirming the importance of Nab2-mediated NuRD and histone deacetylation in blocking fibrotic Egr-1 activity. We also investigated the modulation of matrix homeostasis using Nab2-null mice [76]. These mice were produced at the expected Mendelian ratios, and when sacrificed at six months of age, showed no overt phenotype. However, careful examination of the skin from Nab2-null mice showed dermal sclerosis (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the Nab2-null skin had increased collagen accumulation and elevated levels of COL1A1 mRNA compared to wildtype controls, and Nab2-null MEFs showed constitutive Egr-1 signaling and up-regulation of collagen synthesis in vitro [76]. RNAi-mediated knockdown of endogenous Nab2 in normal fibroblasts was similarly associated with increased Egr-1 activity and enhanced TGF-ß responses.

Figure 5. Nab2 is an endogenous negative modulator of fibrosis.

A. Schematic of the endogenous inhibitory activity of Nab2 in fibrosis. B. Dermal sclerosis in Nab2-null mice. Picrosirius Red stain, viewed under polarized light microscope. Original magnification ×100. B. Immunohistochemistry. Lung tissues from patients with SSc-associated pulmonary fibrosis undergoing lung transplantation surgery and normal donor lungs were examined using antibodies against Nab2. Original magnification ×100.

Interestingly, examination of skin and lung biopsies from patients with SSc showed a marked increase in Nab2 expression in the lesional tissue compared to healthy controls, which showed virtually absent Nab2 expression. In the SSc biopsies, Nab2 was often localized within the nucleus, and was found in epidermal cells, dermal blood vessels and infiltrating round cells [76]. In normal lungs low levels of Nab2 were detected (Fig. 5C). In contrast, SSc lungs showed a marked increase in Nab2 expression at fibrotic loci. Expression was most prominent in lymphocytes, macrophages, airway-lining cells, interstitial fibroblasts, and alveolar epithelial cells. Based on these intriguing observations, we suggested that Nab2 might be a novel endogenous inhibitor of TGF-ß responses and fibrosis via negative regulation of Egr-1 signaling. Interestingly, genome-wide expression profiling showed that not all TGF-ß responses were equally abrogated by Nab2 (Bhattacharyya S et al, unpublished). In the absence of Nab2, unopposed Egr-1 activity might drive constitutive fibrotic responses, or result in exaggerated fibrotic responses upon stimulation by TGF-ß. In SSc, a relative imbalance between elevated Egr-1 levels and only a modest increase in regulatory Nab2 would favor fibrotic signaling, and may contribute to sustained fibroblast activation and progressive fibrogenesis.

Egr-1 plays a role in fibrosis: insights from animal models

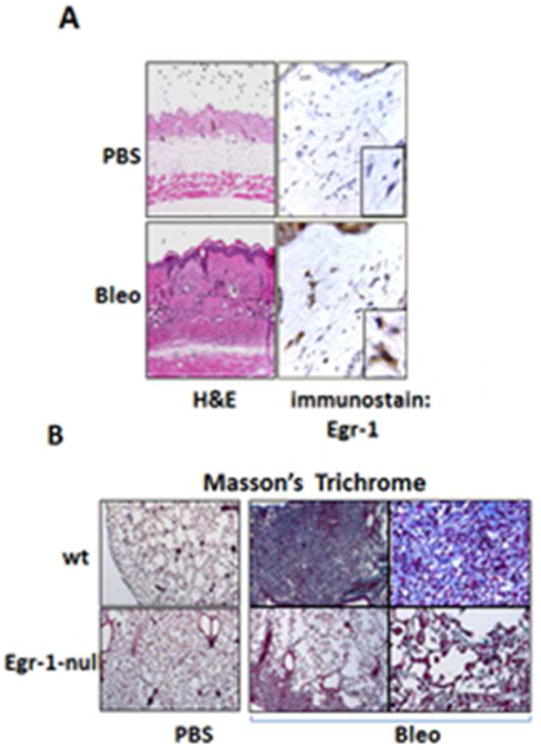

Recent studies highlight a consistent association between aberrant Egr-1expression and fibrosis in animal models of disease. Elevated Egr-1 was noted in the lungs of transgenic mice developing pulmonary fibrosis driven by TGF-ß, IL-13, or activated FasL [41,42,77]. Induction of Egr-1 in these mouse models results in complex responses that include apoptosis, inflammation, alveolar remodeling and eventually fibrosis. Elevated Egr-1 was also observed in the gut in mice with chronic experimental colitis [78], and in the liver of rats with ethanol-induced fibrosis [79]. In the skin, Egr-1 expression was found to be elevated in mice with bleomycin-induced scleroderma, with Egr-1 principally localized within fibroblastic cells in the reticular dermis [33] (Fig. 5). On the other hand, Egr-1 deficiency ameliorates experimental fibrosis induced by diverse insults. For instance, cardiac hypertrophy induced by catecholamine [43], and bleomycin-induced skin and lung fibrosis [34] (Fig. 6), were shown to be reduced in Egr-1-null mice. Therapeutic modulation of Egr-1 in rats by introduction of a DNA enzyme targeting Egr-1 into tubular interstitial fibroblasts ameliorated the development of renal fibrosis in UUO [80]. Furthermore, Egr-null mice displayed basal airspace enlargement, resisted cigarette-smoke induced autophagy, apoptosis, and emphysema thus can be used as novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of cigarette smoke induced lung injury [81,82].

Figure 6. Egr-1 modulates experimental skin and lung fibrosis.

Egr-1-null mice and wildtype littermates received daily s.c. injections of PBS or bleomycin for up to 21 days and lesional skin and lungs were examined. A. H&E stain, left panel; immunohistochemistry using antibodies to Egr-1, right panel. Magnification: ×400; ×1000 (inset, left). B. Reduced lung fibrosis in Egr-1 null mice. Masson's trichrome stain. Original magnification ×25 and ×100.

There exists some controversy regarding the profibrotic role of Egr-1. In one study, hepatic fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced was exacerbated in mice lacking Egr-1[83]. In this liver fibrosis model, Egr-1-null mice demonstrated a more significant oval cell response compared to wildtype mice, suggesting exaggerated liver injury induced by CCl4. Indeed, a subsequent study from the same group showed that liver injury in the Egr-1 null mice was accompanied by reduced inflammation, and production of TNF-α and nitric oxide synthetase which are thought to be hepatoprotective [84]. These observations indicate that the fibrotic role of Egr-1 is context dependent, and is determined by the tissue of its expression and the nature of the injury eliciting its production. Moreover, these findings also highlight the important role of inflammation in promoting tissue repair. In contrast, Egr-1 did not modulate the severity of liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation, despite of decrease in both liver inflammation and injury in the Egr-1 null mice [85].

In an attempt to directly investigate the role of Egr-1 in fibrosis, we generated transgenic mice with fibroblast-specific Egr-1 overexpression [34]. Egr-1 was regulated by the Col1A2 promoter which also expressed lacZ as a reporter of gene expression. Interestingly, we found that Egr-1 transgenic mice did not develop spontaneous fibrosis, likely due to the post-natal silencing of the COL1A2 promoter, as previously reported [86]. However, Col1A2-Egr-1 transgenic mice showed exaggerated healing in response to a cutaneous incisional wound with increased collagen accumulation and the formation of a dense and highly cross-linked scar [34]. These observations are consistent with a dominant role of Egr-1 in orchestrating fibrotic responses in injured fibroblasts.

Egr-1 and lung injury

During the past decade, multiple studies have highlighted the fundamental role of Egr-1 in the pathogenesis of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. In the mouse, cigarette smoke induces a marked increase in pulmonary expression of Egr-1 in emphysema-susceptible AKR/J mice, but not in emphysema-resistant NZWLac/J mice [87]. On the other hand, Egr-1-null mice were resistant to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema [81]. Lungs from patients with COPD showed increased Egr-1 expression accompanied by signs of autophagy and apoptosis. Enhanced Egr-1 expression in the emphysematous lungs was most evident in vascular and bronchial smooth muscle cells and alveolar macrophages [82]. In vitro, treatment of lung fibroblasts with cigarette smoke extract induced the production of MMP-2 via activation of Egr-1[88]. In lung epithelial cells, cigarette smoke extract enhanced the binding of Egr-1 to the promoter of the autophagy gene LC3B. These studies demonstrate that in the lung Egr-1 plays a critical role in promoting MMP-2 secretion, autophagy and apoptosis in response to cigarette smoke, and directly contributes to the pathogenesis of emphysema.

Does aberrant Egr-1 expression or function have an important role in fibrosing diseases?

To date, the evidence linking Egr-1 and human fibrotic disorders is largely correlative. Egr-1 expression is elevated in atherosclerotic plaques and its expression is correlated with the degree of local collagen accumulation [89]. Elevated Egr-1 expression is seen in the lungs from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [46]. Moreover, we recently demonstrated elevated Egr-1 expression in skin and lung biopsies from patients with SSc [33] (Fig. 4). Quantitative analysis showed that SSc patients with early-stage disease (<3 years duration) had a 20-fold and 10-fold increase in Egr-1-positive fibroblasts in the lesional dermis compared to patients with late-stage disease (>3 years), and healthy controls, respectively. Moreover, a trend toward a negative correlation between Egr-1 expression and disease duration was noted. An intriguing recent study used an unbiased genome-wide expression profiling approach to compare gene expression in the lungs from IPF patients with stable versus rapidly progressive disease [90]. In this analysis, elevated Egr-1 was found to be a marker for more rapid progression of disease. Elevated Egr-1 expression was also found in peripheral blood cells from patients with SSc-related pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [91], and in the lungs from patients with idiopathic PAH [92]. In these patients, Egr-1 was detected in pulmonary vessels with medial hypertrophy and neointimal lesions. It is noteworthy in this regard that flow-associated PAH in a rodent model is associated with up-regulation of Egr-1[92].

Further evidence linking Egr-1 with fibrosing disease comes from transcriptional profiling in SSc. Using genome-wide analysis of RNA isolated from Egr-1-transfected normal skin fibroblasts, we experimentally derived a fibroblast “Egr-1-responsive gene signature” comprising over 600 genes [53]. The expression of the Egr-1 signature was then evaluated in SSc skin biopsies [53,93,94]. A distinct intrinsic subset of biopsies comprising patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc was found to have strong expression of the Egr-1 signature, consistent with active Egr-1-mediated signaling in these tissues. These results further highlight the association of Egr-1 signaling with skin fibrosis in a subset of SSc patients, and suggest that patients within this subset might be responsive to therapeutic strategies targeting Egr-1.

Summary and perspectives

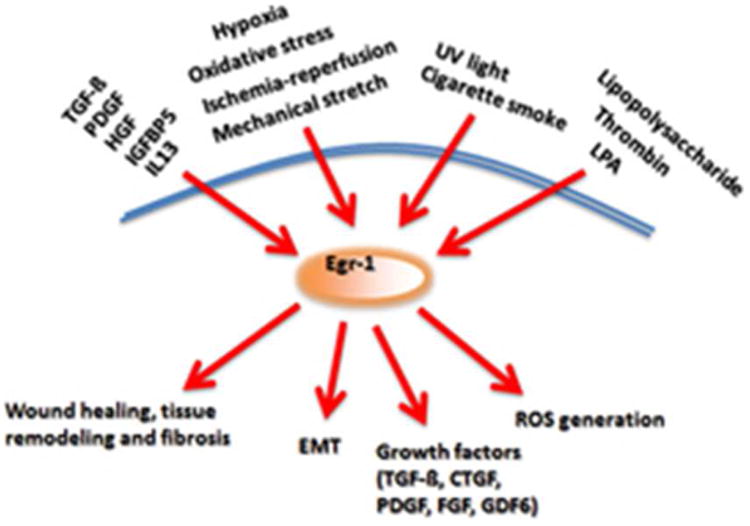

While Egr-1 has long been considered to be an important mediator of cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis, recent studies expand on the spectrum of the recognized biological activities associated with this transcription factor by highlighting its potential role in physiological tissue repair and pathological fibrosis. Egr-1 expression is induced in a variety of cell types by TGF-ß and other fibrogenic stimuli, and in turn, Egr-1 directly stimulates the production of collagen, matrix accumulation, ROS generation, myofibroblast differentiation and EMT, as well as the secretion of TGF-ß, PDGF and other fibrogenic growth factors and cytokines (Fig. 7). Each of these factors contributes to the development and persistence of fibrosis. Fibrotic tissues in a variety of human diseases and animal models show increased Egr-1 accumulation in affected organs, and evidence of active Egr-1-dependent signaling. Indeed, the presence of the “Egr-1 signature” potentially predicts more rapid fibrosis progression in SSc and IPF. Moreover, vascular remodeling in both idiopathic and SSc-associated PAH, is also characterized by elevated Egr-1 expression in lesional tissue. Though some controversy regarding the profibrotic or antifibrotic role of Egr-1 exists, especially in liver, where Egr-1 was thought to be hepatoprotective.

Figure 7.

Schematic depiction of Egr-1 biology in the context of fibrosis. Egr-1 induction triggered by growth factors, hypoxia, oxidative stress, mechanical stretch, ischemia-reperfusion, LPS, thrombin and other stimuli initiates Egr-1-mediated responses including EMT, growth factor secretion, matrix production and ROS generation, culminating in tissue remodeling and fibrosis.

We now view Egr-1 as a conductor of the fibrogenic orchestra whose misbehavior results in cacophony (fibrosis) while a pleasant conductor results in harmony (normal wound healing). The identification of the players -molecules and pathways - aberrantly expressed or activated during fibrogenesis opens the door for the development of selective organ specific targeting strategies to control fibrosis. While there are no specific pharmacological inhibitors of Egr-1, several drugs in current clinical use display potent inhibitory effects on Egr-1 induction or activity. Drugs that appear to show a repressive effect on Egr-1 include mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, simvastatin, imatinib mesylate, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone [51,55,95-99]. These agents might be considered as candidates for evaluation of their anti-fibrotic efficacy in a drug “repurposing” strategy. Intriguingly, a recently identified peptidomimetic, derived from endostatin, that had potent anti-fibrotic activity, was shown to reduce the expression of Egr-1 in organ fibrosis [52]. Much remains to be learned regarding the unique and redundant functions of the various Egrs in fibrosis, and their complex regulation by Nab2 and related endogenous inhibitors. Nevertheless, in light of the central role that Egr-1 appears to have as a “conductor” of the complex fibrosis orchestra, targeting Egr-1 expression/activity might be a novel therapeutic strategy to control fibrosis in a subset of patients to control pathological fibrogenesis [100].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR-04239), Department of Defense (DOD PR054101) and the Scleroderma Foundation. We thank Carol Feghali-Bostwick (University of Pittsburgh) for providing lung tissues.

Footnotes

Microarray data have been deposited at GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; accession no. GSE27165. All data are MIAME compliant.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to researching data, discussing content, writing, and review/editing of the manuscript before subscription.

References

- 1.Wynn TA. Fibrosis under arrest. Nat Med. 2010;16:523–525. doi: 10.1038/nm0510-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Varga J. Understanding fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: shifting paradigms, emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:42–54. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehal WZ, Iredale J, Friedman SL. Scraping fibrosis: expressway to the core of fibrosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:552–553. doi: 10.1038/nm0511-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. TGF-beta signaling: a tale of two responses. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milbrandt J. A nerve growth factor-induced gene encodes a possible transcriptional regulatory factor. Science. 1987;238:797–799. doi: 10.1126/science.3672127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gashler A, Sukhatme VP. Early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1): prototype of a zinc-finger family of transcription factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;50:191–224. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svaren J, Sevetson BR, Apel ED, et al. NAB2, a corepressor of NGFI-A (Egr-1) and Krox20, is induced by proliferative and differentiative stimuli. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3545–3553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo MW, Sevetson BR, Milbrandt J. Identification of NAB1, a repressor of NGFI-A-and Krox20-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6873–6877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan R, Mager GM, Ward RM, et al. NAB2 represses transcription by interacting with the CHD4 subunit of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15129–15137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrengruber MU, Muhlebach SG, Sohrman S, et al. Modulation of early growth response (EGR) transcription factor-dependent gene expression by using recombinant adenovirus. Gene. 2000;258:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjoberg J, Le L, Imrich A, et al. Induction of early growth-response factor 1 by platelet-derived growth factor in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L817–825. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00190.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan SF, Fujita T, Lu J, et al. Egr-1, a master switch coordinating upregulation of divergent gene families underlying ischemic stress. Nat Med. 2000;6:1355–1361. doi: 10.1038/82168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaggioli C, Deckert M, Robert G, et al. HGF induces fibronectin matrix synthesis in melanoma cells through MAP kinase-dependent signaling pathway and induction of Egr-1. Oncogene. 2005;24:1423–1433. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guha M, O'Connell MA, Pawlinski R, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in human monocytic cells mediates tissue factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha expression by inducing Elk-1 phosphorylation and Egr-1 expression. Blood. 2001;98:1429–1439. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li CJ, Ning W, Matthay MA, et al. MAPK pathway mediates EGR-1-HSP70-dependent cigarette smoke-induced chemokine production. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1297–1303. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00194.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann K, Thiel G. Epidermal growth factor and thrombin induced proliferation of immortalized human keratinocytes is coupled to the synthesis of Egr-1, a zinc finger transcriptional regulator. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85:381–391. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossler OG, Thiel G. Thrombin induces Egr-1 expression in fibroblasts involving elevation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, phosphorylation of ERK and activation of ternary complex factor. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyoda T, Zhang F, Sun L, et al. Lysophosphatidic Acid Induces Early Growth Response-1 (Egr-1) Protein Expression via Protein Kinase Cdelta-regulated Extracellular Signal- regulated Kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) Activation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22635–22642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.335695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchwalter G, Gross C, Wasylyk B. Ets ternary complex transcription factors. Gene. 2004;324:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasan RN, Schafer AI. Hemin upregulates Egr-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via reactive oxygen species ERK-1/2-Elk-1 and NF-kappaB. Circ Res. 2008;102:42–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midgley VC, Khachigian LM. Fibroblast growth factor-2 induction of platelet-derived growth factor-C chain transcription in vascular smooth muscle cells is ERK-dependent but not JNK-dependent and mediated by Egr-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40289–40295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagel JI, Deindl E. Early growth response 1--a transcription factor in the crossfire of signal transduction cascades. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2011;48:226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao X, Mahendran R, Guy GR, et al. Detection and characterization of cellular EGR-1 binding to its recognition site. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16949–16957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae MH, Jeong CH, Kim SH, et al. Regulation of Egr-1 by association with the proteasome component C8. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, de Belle I, Liang H, et al. Coactivating factors p300 and CBP are transcriptionally crossregulated by Egr1 in prostate cells, leading to divergent responses. Mol Cell. 2004;15:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang RP, Fan Y, deBelle I, et al. Egr-1 inhibits apoptosis during the UV response: correlation of cell survival with Egr-1 phosphorylation. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:96–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, Zhang SS, Saito K, et al. PTEN regulation by Akt-EGR1-ARF-PTEN axis. EMBO J. 2009;28:21–33. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manente AG, Pinton G, Tavian D, et al. Coordinated sumoylation and ubiquitination modulate EGF induced EGR1 expression and stability. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krones-Herzig A, Mittal S, Yule K, et al. Early growth response 1 acts as a tumor suppressor in vivo and in vitro via regulation of p53. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5133–5143. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tureyen K, Brooks N, Bowen K, et al. Transcription factor early growth response-1 induction mediates inflammatory gene expression and brain damage following transient focal ischemia. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1313–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCaffrey TA, Fu C, Du B, et al. High-level expression of Egr-1 and Egr-1-inducible genes in mouse and human atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:653–662. doi: 10.1172/JCI8592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khachigian LM. Early growth response-1 in cardiovascular pathobiology. Circ Res. 2006;98:186–191. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200177.53882.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya S, Chen SJ, Wu M, et al. Smad-independent transforming growth factor-beta regulation of early growth response-1 and sustained expression in fibrosis: implications for scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1085–1099. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu M, Melichian DS, de la Garza M, et al. Essential roles for early growth response transcription factor Egr-1 in tissue fibrosis and wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1041–1055. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J, Baron V, Mercola D, et al. A network of p73, p53 and Egr1 is required for efficient apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:436–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron V, Adamson ED, Calogero A, et al. The transcription factor Egr1 is a direct regulator of multiple tumor suppressors including TGFbeta1, PTEN, p53, and fibronectin. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:115–124. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritchie MF, Zhou Y, Soboloff J. WT1/EGR1-mediated control of STIM1 expression and function in cancer cells. Front Biosci. 2012;17:2402–2415. doi: 10.2741/3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SL, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff AH, et al. Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1) Science. 1996;273:1219–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, et al. Multiple pituitary and ovarian defects in Krox-24 (NGFI-A, Egr-1)-targeted mice. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:107–122. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.1.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao Y, Shikapwashya ON, Shteyer E, et al. Delayed hepatocellular mitotic progression and impaired liver regeneration in early growth response-1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43107–43116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee CG, Cho SJ, Kang MJ, et al. Early growth response gene 1-mediated apoptosis is essential for transforming growth factor beta1-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:377–389. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho SJ, Kang MJ, Homer RJ, et al. Role of early growth response-1 (Egr-1) in interleukin-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8161–8168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saadane N, Alpert L, Chalifour LE. Altered molecular response to adrenoreceptor-induced cardiac hypertrophy in Egr-1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H796–805. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.3.H796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhattacharyya S, Wu M, Fang F, et al. Early growth response transcription factors: key mediators of fibrosis and novel targets for anti-fibrotic therapy. Matrix Biol. 2011;30:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen SJ, Ning H, Ishida W, et al. The early-immediate gene EGR-1 is induced by transforming growth factor-beta and mediates stimulation of collagen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21183–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasuoka H, Hsu E, Ruiz XD, et al. The fibrotic phenotype induced by IGFBP-5 is regulated by MAPK activation and egr-1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:605–615. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiel G, Cibelli G. Regulation of life and death by the zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:287–292. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedrich B, Janessa A, Artunc F, et al. DOCA and TGF-beta induce early growth response gene-1 (Egr-1) expression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22:465–474. doi: 10.1159/000185495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu HW, Liu QF, Liu GN. Positive regulation of the Egr-1/osteopontin positive feedback loop in rat vascular smooth muscle cells by TGF-beta, ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grotegut S, von Schweinitz D, Christofori G, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces cell scattering through MAPK/Egr-1-mediated upregulation of Snail. EMBO J. 2006;25:3534–3545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu M, Melichian DS, Chang E, et al. Rosiglitazone abrogates bleomycin-induced scleroderma and blocks profibrotic responses through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:519–533. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaguchi Y, Takihara T, Chambers RA, et al. A Peptide derived from endostatin ameliorates organ fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:136ra171. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhattacharyya S, Sargent JL, Du P, et al. Egr-1 induces a profibrotic injury/repair gene program associated with systemic sclerosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1989–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0806188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhattacharyya S, Ishida W, Wu M, et al. A non-Smad mechanism of fibroblast activation by transforming growth factor-beta via c-Abl and Egr-1: selective modulation by imatinib mesylate. Oncogene. 2009;28:1285–1297. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilkes MC, Leof EB. Transforming growth factor beta activation of c-Abl is independent of receptor internalization and regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and PAK2 in mesenchymal cultures. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27846–27854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Wilkes MC, Leof EB, et al. Imatinib mesylate blocks a non-Smad TGF-beta pathway and reduces renal fibrogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 2005;19:1–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2370com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Distler JH, Jungel A, Huber LC, et al. Imatinib mesylate reduces production of extracellular matrix and prevents development of experimental dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:311–322. doi: 10.1002/art.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosh AK, Varga J. The transcriptional coactivator and acetyltransferase p300 in fibroblast biology and fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:663–671. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghosh AK, Yuan W, Mori Y, et al. Smad-dependent stimulation of type I collagen gene expression in human skin fibroblasts by TGF-beta involves functional cooperation with p300/CBP transcriptional coactivators. Oncogene. 2000;19:3546–3555. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhattacharyya S, Ghosh AK, Pannu J, et al. Fibroblast expression of the coactivator p300 governs the intensity of profibrotic response to transforming growth factor beta. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1248–1258. doi: 10.1002/art.20996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collins S, Lutz MA, Zarek PE, et al. Opposing regulation of T cell function by Egr-1/NAB2 and Egr-2/Egr-3. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:528–536. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu B, Symonds AL, Martin JE, et al. Early growth response gene 2 (Egr-2) controls the self-tolerance of T cells and prevents the development of lupuslike autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2295–2307. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sela U, Dayan M, Hershkoviz R, et al. A peptide that ameliorates lupus up-regulates the diminished expression of early growth response factors 2 and 3. J Immunol. 2008;180:1584–1591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le N, Nagarajan R, Wang JY, et al. Analysis of congenital hypomyelinating Egr2Lo/Lo nerves identifies Sox2 as an inhibitor of Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2596–2601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407836102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fang F, Ooka K, Bhattacharyya S, et al. The early growth response gene Egr2 (Alias Krox20) is a novel transcriptional target of transforming growth factor-beta that is up-regulated in systemic sclerosis and mediates profibrotic responses. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2077–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Busquets J, Del Galdo F, Kissin EY, et al. Assessment of tissue fibrosis in skin biopsies from patients with systemic sclerosis employing confocal laser scanning microscopy: an objective outcome measure for clinical trials? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1069–1075. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scharffetter K, Lankat-Buttgereit B, Krieg T. Localization of collagen mRNA in normal and scleroderma skin by in-situ hybridization. Eur J Clin Invest. 1988;18:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1988.tb01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Svaren J, Sevetson BR, Golda T, et al. Novel mutants of NAB corepressors enhance activation by Egr transactivators. EMBO J. 1998;17:6010–6019. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swirnoff AH, Apel ED, Svaren J, et al. Nab1, a corepressor of NGFI-A (Egr-1), contains an active transcriptional repression domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:512–524. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le N, Nagarajan R, Wang JY, et al. Nab proteins are essential for peripheral nervous system myelination. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nn1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laslo P, Spooner CJ, Warmflash A, et al. Multilineage transcriptional priming and determination of alternate hematopoietic cell fates. Cell. 2006;126:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buitrago M, Lorenz K, Maass AH, et al. The transcriptional repressor Nab1 is a specific regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:837–844. doi: 10.1038/nm1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abdulkadir SA, Carbone JM, Naughton CK, et al. Frequent and early loss of the EGR1 corepressor NAB2 in human prostate carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:935–939. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.27102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Melichian DS, et al. The transcriptional cofactor nab2 is induced by tgf-Beta and suppresses fibroblast activation: physiological roles and impaired expression in scleroderma. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matute-Bello G, Wurfel MM, Lee JS, et al. Essential role of MMP-12 in Fas-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:210–221. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fichtner-Feigl S, Young CA, Kitani A, et al. IL-13 signaling via IL-13R alpha2 induces major downstream fibrogenic factors mediating fibrosis in chronic TNBS colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2003–2013. 2013 e2001–2007. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Derdak Z, Villegas KA, Wands JR. Early growth response-1 transcription factor promotes hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in long-term ethanol-fed Long-Evans rats. Liver Int. 2012;32:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakamura H, Isaka Y, Tsujie M, et al. Introduction of DNA enzyme for Egr-1 into tubulointerstitial fibroblasts by electroporation reduced interstitial alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) rats. Gene Ther. 2002;9:495–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen ZH, Kim HP, Sciurba FC, et al. Egr-1 regulates autophagy in cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang W, Yan SD, Zhu A, et al. Expression of Egr-1 in late stage emphysema. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64646-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pritchard MT, Nagy LE. Hepatic fibrosis is enhanced and accompanied by robust oval cell activation after chronic carbon tetrachloride administration to Egr-1-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2743–2752. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pritchard MT, Cohen JI, Roychowdhury S, et al. Early growth response-1 attenuates liver injury and promotes hepatoprotection after carbon tetrachloride exposure in mice. J Hepatol. 2010;53:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim ND, Moon JO, Slitt AL, et al. Early growth response factor-1 is critical for cholestatic liver injury. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:586–595. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ponticos M, Abraham D, Alexakis C, et al. Col1a2 enhancer regulates collagen activity during development and in adult tissue repair. Matrix Biol. 2004;22:619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reynolds PR, Cosio MG, Hoidal JR. Cigarette smoke-induced Egr-1 upregulates proinflammatory cytokines in pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:314–319. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0428OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ning W, Dong Y, Sun J, et al. Cigarette smoke stimulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity via EGR-1 in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:480–490. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0106OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bot PT, Hoefer IE, Sluijter JP, et al. Increased expression of the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway, endoglin, and early growth response-1 in stable plaques. Stroke. 2009;40:439–447. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boon K, Bailey NW, Yang J, et al. Molecular phenotypes distinguish patients with relatively stable from progressive idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) PLoS One. 2009;4:e5134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grigoryev DN, Mathai SC, Fisher MR, et al. Identification of candidate genes in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Transl Res. 2008;151:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dickinson MG, Bartelds B, Molema G, et al. Egr-1 expression during neointimal development in flow-associated pulmonary hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2199–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Milano A, Pendergrass SA, Sargent JL, et al. Molecular subsets in the gene expression signatures of scleroderma skin. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sargent JL, Milano A, Bhattacharyya S, et al. A TGFbeta-responsive gene signature is associated with a subset of diffuse scleroderma with increased disease severity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:694–705. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Farivar AS, MacKinnon-Patterson B, Barnes AD, et al. The effect of anti-inflammatory properties of mycophenolate mofetil on the development of lung reperfusion injury. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2235–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bea F, Blessing E, Shelley MI, et al. Simvastatin inhibits expression of tissue factor in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E deficient mice independently of lipid lowering: potential role of simvastatin-mediated inhibition of Egr-1 expression and activation. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Farivar AS, Mackinnon-Patterson BC, Barnes AD, et al. Cyclosporine modulates the response to hypoxia-reoxygenation in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Okada M, Yan SF, Pinsky DJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) activation suppresses ischemic induction of Egr-1 and its inflammatory gene targets. FASEB J. 2002;16:1861–1868. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0503com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wan H, Yuan Y, Liu J, et al. Pioglitazone, a PPAR-gamma activator, attenuates the severity of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis by modulating early growth response-1 transcription factor. Transl Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leask A. Egr-ly awaiting a “personalized medicine” approach to treat scleroderma. J Cell Commun Signal. 2012;6:111–113. doi: 10.1007/s12079-012-0160-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]