Abstract

Background

We hypothesized that an intervention which improves nursing home (NH) staff connections, communication, and problem solving (CONNECT) would improve implementation of a falls reduction education program (FALLS).

Design

Cluster randomized trial.

Setting

Community (n=4) and VA NHs (n=4)

Participants

Staff in any role with resident contact (n=497).

Intervention

NHs received FALLS alone (control) or CONNECT followed by FALLS (intervention), each delivered over 3-months. CONNECT used story-telling, relationship mapping, mentoring, self-monitoring and feedback to help staff identify communication gaps and practice interaction strategies. FALLS included group training, modules, teleconferences, academic detailing, and audit/feedback.

Measurements

NH staff completed surveys about interactions at baseline, 3 months (immediately following CONNECT or control period), and 6 months (immediately following FALLS). A random sample of resident charts was abstracted for fall risk reduction documentation (n=651). Change in facility fall rates was an exploratory outcome. Focus groups were conducted to explore changes in organizational learning.

Results

Significant improvements in staff perceptions of communication quality, participation in decision making, safety climate, care giving quality, and use of local interaction strategies were observed in intervention community NHs (treatment by time effect p=.01), but not in VA NHs where a ceiling effect was observed. Fall risk reduction documentation did not change significantly, and the direction of change in individual facilities did not relate to observed direction of change in fall rates. Fall rates did not change in control facilities (2.61 and 2.64 falls/bed/yr), but decreased by 12% in intervention facilities (2.34 to 2.06 falls/bed/yr); the effect of treatment on rate of change was 0.81 (0.55, 1.20).

Conclusion

CONNECT has the potential to improve care delivery in NHs, but the trend toward improving fall rates requires confirmation in a larger ongoing study.

Keywords: nursing homes, accidental falls, staff education

Introduction

Improving care for frail older adults residing in nursing homes (NHs) remains a national priority. Because many adverse health outcomes in older adults result from the interaction of multiple risk factors rather than from a single underlying problem, it is rare that interventions focused on a single problem result in substantial improvements. Rather, multifactorial risk reduction interventions have been proposed to be more appropriate for many of the “geriatric syndromes” that affect NH residents.1 Multifactorial interventions have been developed for NH falls, incontinence, pressure ulcer prevention, behavioral disturbance, and insomnia.2–8

Randomized controlled studies suggest that such multifactorial interventions are effective in improving outcomes when study staff implement their components; however, studies which have attempted to train existing NH staff to implement multifactorial risk reduction have generally not been as successful.9 Fall prevention exemplifies this problem. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a trend that multifactorial fall risk reduction interventions reduced fall rates by 22%, but the result was not statistically significant.10 When one examines the individual studies that were included in this calculation, those which used external study staff to complete risk reduction activities demonstrated substantial reductions in fall rates2,11–13, while those which trained nurses or nurse aides (NAs) to perform fall risk reduction did not6,14,15. Indeed, the study by Kerse et al. which contributed substantially to the negative finding in the meta-analysis, showed an increase in fall rates when nurses and nurse aides are trained in fall prevention, perhaps due to increased staff awareness and therefore reporting of falls.14

Our prior research suggests several reasons why multifactorial interventions are not successful when taught to existing NH staff. Implementing such interventions requires accurate information about resident behaviors, health status, medications and other risk factors to be available to multiple members of the team so that tailored risk reduction plans can be developed. In addition, they require ongoing coordination among direct care and interdisciplinary staff to implement the components of the risk reduction plan. Our prior in-depth case study of NH staff behaviors16 revealed that staff often lack the connections needed to obtain and share pertinent resident information.17–20 Common local interaction strategies used by busy staff to avoid additional work or risk of punishment include “being aloof”, keeping information to yourself, working alone without asking for or offering assistance, and a “not my job” attitude.21–23 These practices result in thin connections, little information flow, and limited use of diverse perspectives and frameworks (cognitive diversity)24 to make sense of a resident’s fall risk factors (sensemaking)25. Teaching staff to perform multifactorial risk factor reduction is unlikely to be effective unless these parameters are first strengthened.

Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled pilot test of the CONNECT intervention, which is designed to improve NH staff connections, information exchange, use of cognitive diversity and sense-making. We hypothesized that NHs which received CONNECT prior to a gold-standard falls reduction training program would have larger changes in measures of staff communication and fall reduction documentation compared to NHs which received the fall reduction program training program alone. The change in facility fall rates was measured as an exploratory outcome to estimate an effect size for a subsequent larger trial testing the impact on resident outcomes.

Methods

Design and Setting

This was a cluster-randomized controlled trial testing the impact of CONNECT and FALLS, compared to FALLS alone, on measures of staff communication, fall risk reduction documentation, and (as an exploratory measure) facility fall rates. Four community nursing homes and four Veterans Affairs (VA) Community Living Centers in North Carolina and Virginia were included (NHs). Study NHs provided post-acute skilled nursing/rehabilitation services and long-term care, and had at least 90 beds. Each NH was matched to a similar facility based on VA or community status, academic affiliation and chain ownership; NHs were randomized within each pair to receive either CONNECT followed by FALLS or FALLS alone. A study team member blinded to NH identity assigned treatment groups using a random number generator.

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at Duke University and the four participating VA Medical Centers. Directors of Nursing and NH Administrators in each facility signed written informed consent.

Participants

All NH employees aged 18 years or over who had direct resident contact were eligible for participation. Temporary agency staff and staff working only as needed were excluded. Participants’ departments included nursing, rehabilitation, social work, dietary services, environmental services, activities, medical services, and administration. All eligible participants were invited to participate in educational sessions designated as quality improvement where no consent was required [CONNECT classroom sessions (intervention facilities only); FALLS team training, teleconferences, online modules, and academic detailing sessions, described below]. Participants who provided informed consent were asked to complete staff surveys, and to attend additional CONNECT study activities [(intervention NHs only) group mapping, individual mapping, unit-based mentoring]. (CONSORT diagram, Figure 1)

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of study enrollment and follow-up. Participation in study activity for FALLS includes completing one or more of the following: falls team training, case-based modules, teleconference, academic detailing, audit and feedback. Participation in study activity for CONNECT includes one or more of the following: classroom sessions, mapping sessions, unit based mentoring, self-monitoring.

Residents who were aged 50 years and over, experienced 1 or more falls during the study period, and remained in the NH at least 72 hours after the fall were eligible for chart abstraction, described below. Falls were defined as per the Resident Assessment Inventory as “an unintentional change in position coming to rest on the ground, floor or onto the next lower surface”26 and included witnessed and reported falls. A list of potentially eligible residents who fell was obtained by reviewing both facility incident report logs and Minimum Data Set records. In VA facilities all residents with 1 or more fall had their electronic medical records reviewed for fall risk reduction documentation (see below); in community facilities a random subset of 35 eligible residents per facility had their records abstracted. A waiver of informed consent and HIPAA authorization was obtained for chart abstraction.

Interventions

Details of the CONNECT and FALLS interventions have been described previously27, and components are listed in Appendix A. 28 CONNECT was developed based on case study research 17,22,29–31, complexity science and social constructivist learning theoretical models. By participating in intervention activities, staff were encouraged to: 1) critically evaluate their relationships with co-workers and set goals for improvement; 2) share resident information within and between disciplines and using multiple perspectives to make sense of it; and 3) practice interaction strategies which facilitate connection, information flow, and use of cognitive diversity in sense-making. Delivery methods included group story-telling and role play, individual and group-level relationship mapping, individual mentoring on the nursing unit, and self-monitoring of communication patterns and use of interaction strategies.

FALLS was a staff education and quality improvement program based on AHRQ’s falls management program32, and included both didactic and interactive learning activities. Each facility was asked to form a Falls Team. The Falls Team members received a half-day training session followed by 11 weekly teleconferences which covered fall multifactorial risk reduction strategies and basic quality improvement processes. Case-based self-study modules were developed for nursing assistants, licensed nursing staff, and medical/pharmacy staff; modules were available over the Internet or in paper form. Academic detailing sessions for small groups of direct care staff were conducted twice at each nursing unit; these were facilitated discussions about real resident fallers that modeled risk factor identification and modification. Finally, audit and feedback of the facility’s fall risk reduction documentation in comparison with other study NHs was provided to the Falls Team.

CONNECT and FALLS were delivered by separately trained research interventionists over 12 weeks each. Intervention dose and fidelity were monitored by other research team members on 10% of intervention components.

Data Collection

Staff measures of communication

Staff who had provided informed consent were asked to complete surveys at baseline, 3 months (following CONNECT or control period) and 6 months (following FALLS). Measures included demographic information and scales of communication openness33, accuracy33 and timeliness34; participation in decision making instrument35; psychological safety36; safety organizing scale37 (a measure of safety culture), a quality of caregiving scale, and a local interaction strategies scale which were developed for this study. Most of these scales have been previously validated in the NH setting, and all were written on a 6th grade reading level; additional detail about the scale domains, response range, and most relevant setting of validation is found in Appendix B. Focus groups with direct care and management staff were also conducted (n=2 in each facility) to obtain a richer understanding of the interventions’ impact on the work environment; the methods and results from these have been reported previously.38

Fall risk reduction measures. We chose to evaluate the NH’s fall risk reduction documentation in a sample of residents who had experienced a fall and for whom fall prevention was clearly warranted. Although facilities may have differed in the quality of their fall reduction efforts among residents at risk for falls but who had not yet fallen, it was not feasible to review all records in the facility, nor was there a validated fall risk measure consistently documented for all residents across all facilities. Resident fallers’ medical records were abstracted for demographic information, time remaining in the NH after their fall (if less than the 30 days after their fall), and co-morbidities associated with falls risk. Documentation of interventions targeting fall risk factors within 30 days of the first fall were recorded including measurement and treatment of orthostatic hypotension, psychoactive medication reduction, calcium and vitamin D supplements, gait or assistive device intervention (e.g., physical or occupational therapy assessment), vision assessment or intervention, environmental modification, footwear modification, and toileting program. In community NHs, charts were abstracted by trained RNs who were blinded to intervention status; in VA NHs, study staffing limitations precluded blinding. In all facilities, inter-rater reliability measured by simple agreement was maintained at >90% on a random 5% sample of charts.

Facility fall rates

Facility fall rates were calculated as an exploratory measure. The total number of falls in the 6 month period before the intervention period and 6 months following the intervention period were divided by the NHs’ occupied bed days of care to determine the falls/bed/year. Falls were ascertained from facility fall logs, incident reports, and the Minimum Data Set; occupied bed days were calculated from daily census data provided by each facility. The proportion of falls resulting in an injury (defined as requiring urgent medical assessment or imaging, pain lasting at least 24 hours, new skin tear or bruise) and the proportion of fallers who fell more than once were also calculated.

Analysis

An intention to treat analysis strategy was used. Hierarchical linear modeling with SAS PROC Glimmix was used to account for clustering; this procedure is useful when there are multi-level, nested sources of variability such as patients and staff clustering within nursing homes. The Glimmix procedure analyzes both individual and group level trajectories of change over time, and can be used to estimate models where persons within clusters are changing over time.

Descriptive, baseline, and follow-up statistics were obtained for all dependent variables; initial analyses tested each dependent variable for violations of distributional assumptions (normality, skew, etc.) and employed logarithmic or other transformation where necessary. The study aims sought to describe the impact of CONNECT plus FALLS, compared to FALLS alone, on staff measures of communication, fall risk reduction documentation, and facility fall rates (exploratory) over time. For each aim, models were first estimated for the dependent variable assuming that the effect of time did not vary with treatment. We then tested for a time by treatment interaction by adding a product term to the model. To control on between-person differences prior to the intervention, we included a baseline measure of each dependent variable as a control in each analysis. We also controlled on facility and individual-level potential confounders when they were related to the independent variable of interest. The confounders considered included: age, gender, race, history of stroke, peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, visual impairment, cognitive impairment, assistive device use, fall in the previous 6 months, ambulatory status, facility bed-size and staffing levels. Because this was a pilot study, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Because the analysis examined trajectories in staff perception of communication over time, only data from staff completing a baseline and at least 1 follow-up survey were included. There were no missing data for the fall rate or fall risk reduction documentation outcomes. Because of substantive differences between VA and community nursing homes and because the funding sources for these sites were distinct, we planned a-priori sub-analyses in which VA and community nursing homes were examined separately.

The power analysis algorithms used to determine cluster size take clustering at the individual level into account. The study was powered to detect a change of 0.20 in staff measures (considered a “moderate” change)39, and a change of 0.55 in fall risk reduction documentation.

Results

Overall, 471 staff members provided informed consent and completed at least 1 survey. Demographic characteristics of staff participants were well balanced (Table 1) except that there was more Caucasian staff in intervention NHs. Approximately half of eligible NH staff participated in one or more of the intervention components, similar in intervention and control NHs (Figure 1). Sixty two percent of staff who participated in at least 1 component of CONNECT or FALLS also completed at least 1 survey; surveys were completed by 71% of consented participants at baseline, 47% of participants at 3 months, and 42% at 6 months. Medical records were abstracted on 651 unique residents with falls; characteristics were similarly balanced except for a higher proportion of residents with vision impairment in the intervention NHs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating nursing homes, staff, and resident fallers.

| FALLS only (control group) | CONNECT and FALLS (intervention group) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Nursing Home | n=4 | n=4 |

| Bed size (mean) | 114.3 | 131.3 |

| Facility Type | ||

| VA, academic | 1 | 1 |

| VA, non-academic | 1 | 1 |

| Community non-profit | 1 | 1 |

| Community for-profit | 1 | 1 |

| Staff Participants | n=254* | n=243* |

| Age (%) | ||

| 18–35 years | 22% | 23% |

| 36–55 years | 57% | 54% |

| 56 years and over | 21% | 23% |

| Female (%) | 85% | 87% |

| Race (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 45% | 59% |

| Black | 50% | 37% |

| Other | 5% | 4% |

| Role (%) | ||

| Nursing assistants | 32% | 32% |

| Direct care nurse | 33% | 29% |

| Administrator | 4% | 4% |

| Dietary | 4% | 1% |

| Housekeeping | 1% | 6% |

| Medical staff | 1% | 2% |

| Rehabilitation | 6% | 4% |

| Other | 19% | 22% |

| Residents who Fell | n= 293 | n=358 |

| Mean age (years) | 77.4(12.5) | 79.0(11.4) |

| Female (%) | 30% | 31% |

| Race (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 75% | 78% |

| Black | 19% | 17% |

| Other | 6% | 5% |

| Prior Falls | 53% | 56% |

| Cognitive Impairment | 62% | 64% |

| Parkinsonism | 5% | 10% |

| Neuropathy | 18% | 12% |

| Vision Impairment | 30% | 42% |

| Ambulatory Status | ||

| Fully Independent | 43% | 45% |

| Transfer Independent | 45% | 41% |

| Fully Dependent | 12% | 15% |

| Stroke | 31% | 31% |

Only consented study staff participants who also completed demographic surveys are included on table; demographics were not available for staff who participated in study educational activities that did not require informed consent.

To answer the questions of whether the interventions influenced the staff communication variables, we tested for treatment by time interactions at 3 and 6 months, controlling for baseline scores (Table 2). Both individual and site level clustering were taken into account in significance testing. Significant improvements over time in communication openness and safety culture were observed for the sample as a whole (openness mean score 3.51 to 3.64 [3.7%], p=0.02; safety culture 4.45 to 4.69 [3.6%], p<0.01). In addition, the intervention group had a significant increase in communication timeliness (3.33 to 3.45 [3.6%], p=0.03). When the mean score of all items were combined, control group means decreased slightly over time indicating an overall decline in communication quality (−0.74) while intervention group means improved (0.116), with a trend to a positive treatment by time effect (p=0.06) (Figure 2). This magnitude of change is considered “moderate” in the psychometrics literature,38 and likely represents a meaningful clinical change. When VA and community NHs were examined separately, a ceiling effect was noted on staff communication measures in the VA, that is, the baseline means were near the top range of the scale, thus leaving little room for improvement to be observed; further, the baseline VA means were also significantly higher than those in community NHs. When the analysis was limited to community nursing homes only, we found significant improvements in staff perceptions of communication quality, NA participation in decision making, safety climate, care giving quality, and use of local interaction strategies (p=.01). Using a subset of staff items including communication openness, accuracy and timeliness; local interactions, safety climate, and caregiving quality, a significant treatment by time effect was noted for the full sample with a mean score difference between intervention and control facilities of 0.086 (p<0.01). This subset was only calculated in community NHs, because 1 of the scales was not completed by VA staff due to IRB approval delays.

Table 2.

Staff survey responses (n=292) at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and 6 months after the intervention for intervention and control groups.

| Scale Domain (possible response range) |

Intervention mean (SD) | Control mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=185) |

3 mo. (n=119) |

6 mo. (n=100) |

Baseline (n=188) |

3 mo. (n=129) |

6 mo. (n=118) |

|

| Communication accuracy (1–5) |

2.97 (0.77) | 2.85 (0.49) | 2.88 (0.57) | 3.05 (0.80) | 3.01 (0.58) | 3.00 (0.55) |

| Communication timeliness (1–5) |

3.33 (0.72) | 3.45 (0.70)* | 3.44 (0.70)* | 3.68 (0.71) | 3.69 (0.71) | 3.67 (0.68) |

| Communication openness (1–5) |

3.37 (0.76) | 3.51 (0.80) | 3.43 (0.81) | 3.65 (0.82) | 3.75 (0.81) | 3.73 (0.79) |

| Nurse Aide participation in decision making (1–10) |

4.65 (2.05) | 5.08 (2.10) | 5.00 (2.02) | 5.41 (2.23) | 5.33 (2.38) | 5.32 (2.34) |

| LPN participation in decision making (1–10) |

6.12 (2.11) | 6.52 (2.20) | 6.33 (2.04) | 6.01 (2.18) | 6.11 (2.31) | 6.06 (2.37) |

| Safety culture (1–7) |

4.26 (1.31) | 4.48 (1.22)* | 4.40 (1.37)* | 4.62 (1.33) | 4.69 (1.25)* | 4.93 (1.33)* |

| Psychological safety (1–7) |

4.74 (1.29) | 4.85 (1.16) | 4.76 (1.29) | 5.10 (1.23) | 5.13 (1.22) | 5.16 (1.19) |

| Overall mean | 4.03 (0.80) | 4.10 (0.73) | 4.11 (0.71) | 4.83 (0.84) | 4.74 (0.84) | 4.69 (0.82) |

| Complexity science subset mean** |

3.62 (0.78) | 3.74 (0.75)* | 3.79 (0.68)* | 4.51(0.84) | 4.42 (0.79) | 4.37 (0.78) |

Change over time significant at p < 0.05

Community nursing homes only, includes communication openness, accuracy and timeliness; local interactions; safety climate; and caregiving quality

Figure 2.

Composite staff survey responses at baseline, immediately following intervention, and 3 months after intervention. Treatment by time interaction for all staff items p = 0.06, for complexity science subset items p <0.01. Subset items include communication openness, accuracy and timeliness; local interactions; safety climate, and caregiving quality. Individual survey response ranges were 1–5, 1–7 or 1–10 (appendix B).

To answer the question of whether the intervention influenced the use of fall risk reduction documentation, we calculated a score for each resident who fell using the number of risk reduction measures documented within 1 month of their first fall divided by the number of potential interventions. We calculated the average facility score, indicating the proportion of potential fall risk reduction measures documented for their fallers, comparing scores for the 6 months preceding study initiation and the 6 months following FALLS. Based on initial tests, the dependent variable was treated as normally distributed in our regression models. A re-analysis using poisson regression gave similar results. Baseline scores improved from 24% to 36% for all facilities combined (p=0.30), with no significant difference between intervention and control facilities. In a model adjusted for time at risk and covariates significantly related to fall risk reduction documentation, the treatment by time effect was not significant (p=0.51).

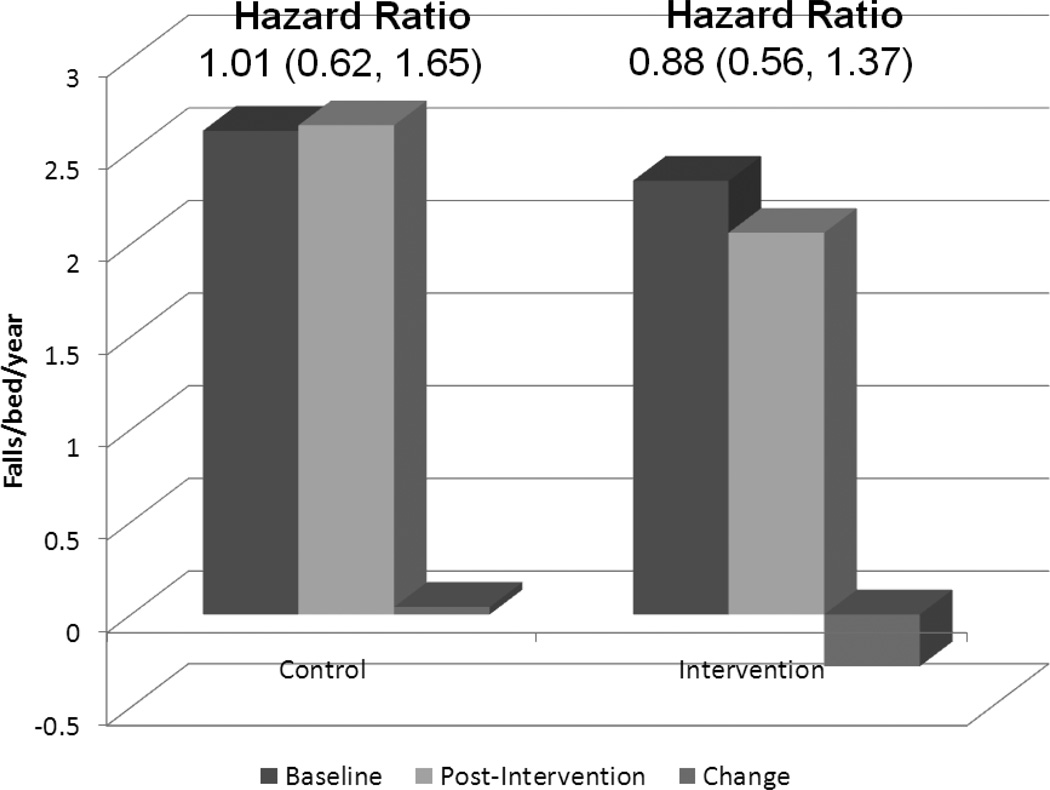

The question of whether facility fall rates responded to the intervention was exploratory, given the limited facility sample size. Negative binomial regression was used to take overdispersion into account. Fall rates increased by 1% in the control group (Rate Ratio 1.1, 95% CI 0.62, 1.65) and decreased by 12% in the intervention group (0.88, 95% CI 0.56, 1.37), from 2.34 to 2.06 falls per bed per year (Figure 3). Being in the intervention group multiplied the rate of decline by 0.81 (0.55, 1.20) but the effect was not statistically significant. Adding time at risk to the models did not change the results. No statistically significant treatment effect was observed in the proportion of fallers who suffered additional falls (45% in control facilities, 48% in intervention facilities), nor in the risk of injurious falls.

Figure 3.

Facility level fall rate (falls/bed/year) in intervention and control NHs in the 6 month baseline and post-intervention periods, and change in fall rates after intervention.

Discussion

With already constrained resources and potential cuts to NH reimbursement looming, adding additional staff to implement risk reduction programs for complex geriatric syndromes such as falls is not feasible. Therefore, identifying ways to increase the existing staff’s capacity to adopt evidence-based practices is an essential part of improving outcomes for frail NH residents.

This pilot study suggests that the CONNECT intervention has the potential to improve resident outcomes through its impact on staff connections, information exchange, use of cognitive diversity and sense-making. Complexity science theory suggests that these form the necessary foundation which allows staff to “self-organize”, creatively problem solve about individual resident issues, and implement an optimal plan to address them.21 CONNECT was developed based on case-study observations of NH staff behaviors, and therefore has substantial construct and face validity. We used social constructivist learning approaches to foster the acquisition of these important processes.

Supporting an impact on staff connections, we found significant improvements in measures of NH staff communication, despite an apparent ceiling effect in VA NHs. Baseline staff communication measures scores were substantially lower in intervention than control sites; this likely reflects chance imbalance in facility work culture or other characteristics despite randomization. Results from the larger trial will be important to ensure that the observed improvement in intervention facilities does not represent a regression to the mean phenomenon. There are important differences between VA and community facilities that may account for the VA ceiling effect including a greater proportion of RN level nurses, higher staffing levels, and lower staff turnover rates; subsequent studies in VA NHs might consider limiting the scale ranges to five and including two negative and three positive response anchors which is recommended to minimize ceiling effects.40 Of our communication measures, only the local interaction scale fully met these criteria. Nevertheless, focus group participants in both VA and community NHs who had received CONNECT reported wider and richer interactions with co-workers within and between disciplines, resulting in more effective fall care plans, compared to focus groups in NHs which had received FALLS only.38 Using mixed method approaches such as this has been suggested as a method for overcoming ceiling effects in quantitative measures.41 This improvement, while it endured over at least 6 months, is potentially vulnerable to high rates of staff turnover, a common issue in NH practice. Strategies we used to promote long-term change in the face of expected high turnover include providing training materials that can be used in new staff orientation, and identifying CONNECT “champions”; these are staff at all levels who are specifically trained to continue individual mentoring on the use of effective local interaction strategies after the study is complete.

It is notable that we did not observe a significant change in fall risk reduction documentation in either study arm. While the FALLS intervention offered a standardized template for fall risk reduction activity documentation, the facilities could choose to adopt it or not at their discretion; in practice most facilities chose to modify existing note templates. Furthermore, the direction of change in fall risk reduction scores did not relate to observed changes in fall rates in individual facilities. Chart abstraction was completed by skilled personnel and inter-rater reliability remained >90%, suggesting that data collection issues were not at fault. Rather, we hypothesize that the documentation of fall risk reduction activities may not reflect the care that is actually delivered at the bedside; for example, an order for prompted voiding may be documented on the chart, but not implemented by nurse aides, or conversely, environmental modifications may be made but not recorded. The use of boilerplate language in care plans or check boxes on post-fall assessment forms further limits the utility of chart abstraction in measuring true changes in risk reduction activities; this phenomenon has been observed in quality improvement programs for other geriatric syndromes in the nursing home such as pressure ulcer prevention.42 Alternative ways of measuring changes in care delivery resulting from quality improvement interventions are needed. For example, staff responses to clinical vignettes have been reported to be superior to chart abstraction in outpatient settings, when standardized patient encounters are used as a gold standard.43

Ultimately, the most important measure of intervention effectiveness is the impact on resident outcomes. While our study was not powered to detect a difference in facility-level fall rates, the direction of change was encouraging and the magnitude of the effect was clinically important. An ongoing randomized controlled trial of CONNECT will ultimately include 24 facilities; if the magnitude of the effect size is similar to that observed in the pilot study it would be statistically significant. If shown to be effective with falls as an indicator condition, CONNECT could be tested as a companion intervention for programs targeting other geriatric syndromes, since it does not target a specific resident issue but rather the underlying staff connections, information exchange, and cognitive diversity required to develop tailored intervention programs, a hallmark of high quality long-term care.

In summary, pilot testing suggests that CONNECT is feasible and acceptable in community and VA NHs. Measures of staff communication improved in community NHs that received CONNECT while declining slightly in control facilities. Decreases in facility-level fall rates were observed in the intervention but not control facilities. Chart abstraction measures of fall risk reduction documentation were insensitive to change and do not appear to relate to changes in fall rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the dedicated nursing home and research staff who participated in this study. The corresponding author affirms that she has listed everyone who contributed significantly to the work.

Funding Source: This work was funded by VA Health Services Research and Development grant EDU 08-417 (Colon-Emeric, PI), and the National Institutes of Nursing Research R56NR003178–09 (Anderson & Colon-Emeric, MPIs).

Sponsor's Role: The sponsor had no role in design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Appendix A. Components of the CONNECT and FALLS Interventions**

| Intervention Components | Rationale/Outcome | Participants | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONNECT | |||

|

CONNECT In-Class Protocols CONNECT Basics (Session 1). Introduces local interaction strategies using storytelling. Participants practice using role-play. CONNECT Advanced (Session 2). Brief review followed by focus on the more advanced strategies of cognitive diversity. Uses storytelling, role-playing, and discussion of participants’ experiences in applying concepts. |

Interdisciplinary learning facilitates skill acquisition, creation of new horizontal and vertical connections among staff, and learning through cognitive diversity. |

All staff | two sessions, 30 min each occurring 2 weeks apart (1.0 hrs total) |

|

Group-to-group maps Session 1. Researcher assists staff to describe actual interactions between work groups (e.g., NAs, LPNs, SW, Dietary, etc.). Session 2. Researcher assists staff to depict new interaction patterns and develop guidelines for improved group-to-group interaction patterns. |

Assists staff to make interaction patterns explicit (develop a group-to-group relationship map), and agree on guidelines for improved interactions. |

Mid-level managers and selected LPNs, NAs. |

two classes, 1-hr each; 1 week apart (2 hrs total) |

|

Individual-to-individual maps Researcher assists staff to draw an individual “relationship map” that defines his/her ideal interactions with selected co-workers in all work groups; reviews strategies for improving interactions. Participants learn to self-monitor and record interactions using relationship maps and recording sheets. |

Assists staff to evaluate relationships. Self- monitoring reinforces and sustains newly acquired behaviors and provides a measure of adherence and behavior change. |

All staff | one session, 30 min (30 min total) |

|

Structured Mentoring During the 2 weeks following each in-class session, the researcher engages each participant in a 10-minute session to discuss and reflect on his/her experiences applying CONNECT concepts. The researcher uses a semi-structured guide to elicit concerns about using the strategies. |

Facilitates authentic learning, which occurs only when learners can directly and independently apply concepts. |

All staff | 2, 10 min sessions (20 min total) |

| FALLS | |||

|

Falls Team Training Session Researcher reviews: 1) role of FALLS Coordinator and Team members; 2) Falls Management Program rationale and main components; 4) toolkit materials; 5) team goals. |

Falls Team members champion fall prevention, identify area to improve, monitor changes. |

FALLS Coordinator, Falls Team, DON |

one session, 4 hours duration |

|

Weekly Teleconference Researcher contacts FALLS team weekly for problem- solving/discussion, and highlights a topic from the Fall Management Program in more depth. Topics include 1) staff fall prevention education; 2) medications and falls 3) patient and family fall education; 4) orthostatic hypotension; 5) vision assessment and intervention; 6) gait and balance assessment and intervention 7) environmental assessment and intervention; 8)challenging behavior management; 9) establishing a culture of safety; 10) audit and feedback; and 11) Wrap-up and re-setting goals |

Reinforces key concepts of multi- factorial risk reduction, supports FALLS Coordinator and maintains enthusiasm. |

FALLS Team, others as invited by team |

11 sessions, 45 min each weekly (8.25 hrs total) |

|

Case-Based Modules Separate modules tailored for nurses, medical providers/pharmacists, and nurse aides. Using case scenarios, describes impact of falls and multifactorial risk reduction strategies pertinent for each group. Online or in paper form. |

Uses case-based learning to impart knowledge and change attitudes about multi-factorial fall risk reduction. |

RNs, LPNs, NAs, MDs, NPs, PAs, Consultant Pharmacists and others |

30–60 min |

|

Academic Detailing NH frontline staff is invited to participate in consultations with the researcher and FALLS Coordinator regarding their most challenging residents with falls, modeling risk factor assessment and multi- factorial interventions. Sessions occur at each nursing station during the day and evening shifts. |

Reinforces key concepts and promotes behavior change and interdisciplinary discussions. |

Nurses, NAs, other interested staff |

two sessions, 20 min each (40 min total) |

|

Audit and Feedback Report Report uses visual (bar graph) and written depictions of the NH’s current practice on fall-related process and outcome measures, and how this compares with peer NHs. |

Identifies areas for improvement, promotes behavior change. |

FALLS team, others as desired by Falls Coordinator |

30 min |

|

Toolbox Data collection instruments, worksheets, posters, patient/family handouts, checklists, fax communication forms |

Provides modifiable tools to assist with communication, implementation, and documentation of multi-factorial risk reduction. |

FALLS team determines dissemination |

Voluntary |

Reprinted with permission of authors27

Appendix B. Staff communication measures, domains, scale, and prior validity studies in nursing home (NH)

| Author Reference |

Domains Measured | Number of Items |

Response Range |

Validation Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts and O’Reilly33 |

Communication openness; Communication accuracy |

5 5 |

1–5 1–5 |

NH |

| Shortell34 | Communication timeliness | 4 | 1–5 | NH |

| Anderson35 | LPN participation in decision-making | 4 | 1–10 | NH |

| Anderson35 | Nurse Aide participation in decision- making |

4 | 1–10 | NH |

| Edmonson, Tucker36 |

Psychological Safety | 3 | 1–7 | Healthcare |

| Vogus and Sutcliff37 |

Safety organizing | 9 | 1–7 | Intensive Care Unit |

| Anderson | Local interaction quality: supervisor, co-worker |

30 | 1–5 | NH, in process |

| Colón-Emeric | Quality of care planning, shift change, personal care, feeding, medical care |

25 | 1–5 | NH, In process |

Footnotes

Meeting Submission: This work was presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, Plenary Paper Session

| CCE | EM | SP | KC | KP | KS | LL | JL | KH | RAA | JB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Employment or Affiliation |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Grants/Fund | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Honoraria | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

Speaker Forum |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Consultant | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Stocks | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Royalties | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

Expert Testimony |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

Board Member |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Patents | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

Personal Relationship |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Author Contributions:

CCE: study design, study implementation, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

EM: study design, study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

SP: study design, study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

KC: study design, study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

KP: study implementation, data acquisition, manuscript preparation

KS: study implementation, data acquisition, manuscript preparation

LL: study design, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

JB: study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

JL: study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

KH: study implementation, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

RAA: study design, study implementation, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript preparation

References

- 1.Tinetti M, Inouye S, Gill T, Doucette J. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273(17):1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen J, Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y. Fall and injury prevention in older people living in residential care facilities. Ann Int Med. 2002;136:733–741. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quigley P, Bulat T, Kurtzman E, Olney R, Powell-Cope G, Rubenstein L. Fall prevention and injury protection for nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(4):284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray W, Taylor J, Meador K, et al. A randomized trial of a consultation service to reduce falls in nursing homes. JAMA. 1997;278(7):557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates-Jensen BM, Alessi CA, Al-Samarrai NR, Schnelle JF. The Effects of an Exercise and Incontinence Intervention on Skin Health Outcomes in Nursing Home Residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(3):348–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neyens JCL, Dijcks BPJ, Twisk J, et al. A multifactorial intervention for the prevention of falls in psychogeriatric nursing home patients, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) Age Ageing. 2009 Mar 1;38(2):194–199. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn297. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, Cynthia Kim E, Harker JO, Josephson KR. Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Nonpharmacological Intervention to Improve Abnormal Sleep/Wake Patterns in Nursing Home Residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(5):803–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovach CR, Logan BR, Noonan PE, et al. Effects of the Serial Trial Intervention on Discomfort and Behavior of Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2006 May 1;21(3):147–155. doi: 10.1177/1533317506288949. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colon-Emeric C, Schenck A, Gorospe J, et al. Translating evidence-based falls prevention into clinical practice in nursing facilities: Results and lessons from a quality improvement collaborative. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006 Sep;54(9):1414–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron I, Gillespie L, Robertson M, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker C, Kron M, Lindemann U, et al. Effectiveness of a Multifaceted Intervention on Falls in Nursing Home Residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(3):306–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyer CAE, Taylor GJ, Reed M, Dyer CA, Robertson DR, Harrington R. Falls prevention in residential care homes: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004 Nov 1;33(6):596–602. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh204. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMurdo M, Millar A, Daly F. A randomized controlled trial of fall prevention strategies in old people's homes. Gerontology. 2000;46(2):83–87. doi: 10.1159/000022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerse N, Butler M, Robinson E, Todd M. Fall prevention in residential care: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004;52:524–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubenstein LZ, Robbins AS, Josephson KR, Schulman BL, Osterweil D. The Value of Assessing Falls in an Elderly PopulationA Randomized Clinical Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113(4):308–316. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RA, Bailey D, Corazzini KN, Ammarell N, Lillie M, Colón-Emeric C. Improving nursing home care: Using case study methods for interdisciplinary research to improve quality."; San Diego, CA. Paper presented at: 56th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colón-Emeric C, Bailey D, Corazzini KN, et al. Patterns of Medical and Nursing staff communication in nursing homes: Implications and insights from complexity science. Qual. Health Res. 2006;16(2):173–188. doi: 10.1177/1049732305284734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colon-Emeric CS, Lekan-Rutledge D, Utley-Smith Q, et al. Connection, regulation, and care plan innovation: a case study of four nursing homes. Health Care Manage. Rev. 2006 Oct-Dec;31(4):337–346. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200610000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corazzini K, Utley-Smith Q, Ammarell N, et al. Improving Nursing Assistant Care Decisions: The Relationship between Supervision and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. The Gerontologist; Orlando, Florida. Paper presented at the 58th Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; November 20, 2005.2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piven ML, Ammarell N, Bailey D, et al. MDS coordinator relationships and nursing home care processes. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2006 Apr;28(3):294–309. doi: 10.1177/0193945905284710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson R, Issel L, McDaniel R. Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems - Relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nurs. Res. 2003;52:12–21. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RA, Ammarell N, Bailey D, Jr., et al. Nurse assistant mental models, sensemaking, care actions, and consequences for nursing home residents. Qual. Health Res. 2005 Oct;15(8):1006–1021. doi: 10.1177/1049732305280773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson RA, Ammarell N, Bailey DE, et al. The power of relationship for high-quality long-term care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2005 Apr-Jun;20(2):103–106. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller CC, Burke LM, Glick WH. Cognitive diversity among upper-echelong executives: Implications for strategic decision processes. Strategic Management Journal. 1998;19(1):39–58. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weick KE. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDS 3.0 RAI Manual. [Accessed May 8, 2013];CMS.gov. 2013 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html.

- 27.Anderson RA, Corazzini K, Porter K, Daily K, McDaniel RR, Colon-Emeric C. CONNECT for quality: protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial to improve fall prevention in nursing homes. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-11. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/17/11/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2009 National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Report, 2009. Rockville, MD: 2011. Sep 5, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson R, Crabtree B, Steele D, McDaniel R. Case study research: The view from complexity science. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(5):669–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson RA, Bailey D, Colon-Emeric C, et al. Theoretical overview of mindfulness and qualitative description of mindful management practices in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(Special Issue 1):54. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colon-Emeric CS, Plowman D, Bailey D, et al. Regulation and mindful resident care in nursing homes. Qual. Health Res. 2010 Sep;20(9):1283–1294. doi: 10.1177/1049732310369337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor J, Parmelee P, Brown H, Ouslander JG Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Falls Management Program: A Quality Improvement Initiative for Nursing Facilities. Atlanta, GA: Emory University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Reilly C, Roberts K. Task group structure, communication, and effectiveness in three organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1977;64:674–681. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, Devers KJ, Simons TL. Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse-physician questionnaire. Medical Care. 1991 Aug;29(8):709–726. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00004. 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson RA, Ashmos DP. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Nursing Participation in Decision Making Instrument; Los Angeles, CA. Paper presented at: 1991 International Nursing Research Conference.1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tucker AL. An Empirical Study of System Improvement by Frontline Employees in Hospital Units. Manufacturing Service Operations Management. 2007 Jan 1;9(4):492–505. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM. The Safety Organizing Scale: Development and Validation of a Behavioral Measure of Safety Culture in Hospital Nursing Units. Medical Care. 2007;45(1):46–54. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244635.61178.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colón-Emeric CS, Pinheiro SO, Anderson RA, et al. Connecting the Learners: Improving Uptake of a Nursing Home Educational Program by Focusing on Staff Interactions. The Gerontologist. 2013 May 23; doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt043. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner D, Schünemann HJ, Griffith LE, et al. The minimal detectable change cannot reliably replace the minimal important difference. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010;63(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moret L, Nguyen JM, Pillet N, Falissard B, Lombrail P, Gasquet I. Improvement of psychometric properties of a scale measuring inpatient satisfaction with care: a better response rate and a reduction of the ceiling effect. BMC Health Services Research. 2007 Dec 3;7:197. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-197. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/7/197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrew S, Salamonson Y, Everrett B, Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM. Beyond the ceiling effect: using a mixed methods approach to measure patient satisfaction. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches. 2011;5(2):52–63. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sales A, Sharp N, Li Y, et al. The association between nursing factors and patient mortality in the Veterans Health Administration: The view from the nursing unit level. Medical Care. 2008;46(9):938–945. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181791a0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peabody J, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Le M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: A prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]