Abstract

Viruses enter into complex interactions within human hosts leading to facilitation or suppression of each other's replication. Upon coinfection, GB virus C (GBV-C) suppresses HIV-1 replication in vivo and in vitro, and GBV-C coinfection is associated with prolonged survival in HIV-infected people. GBV-C is a lymphotropic virus capable of persistent infection. GBV-C infection is associated with reduced T cell activation in HIV-infected humans, and immune activation is a critical component of HIV disease pathogenesis. We demonstrate that serum GBV-C particles inhibited activation of primary human T cells. T cell activation inhibition was mediated by the envelope glycoprotein E2, as expression of E2 inhibited T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated activation of tyrosine kinase (Lck). The region on the E2 protein was characterized and revealed a highly conserved peptide motif sufficient to inhibit TCR-mediated signaling. The E2 region contained a predicted Lck substrate site, and substitution of an alanine or histidine for the tyrosine reversed TCR signaling inhibition. GBV-C E2 protein and a synthetic peptide representing the inhibitory amino acid sequence were phosphorylated by Lck in vitro. The synthetic peptide also inhibited TCR-mediated activation of primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Extracellular microvesicles from GBV-C E2-expressing cells contained E2 protein and inhibited TCR signaling in bystander T cells not expressing E2. Thus, GBV-C reduced global T cell activation via competition between its envelope protein E2 and Lck following TCR engagement. This novel inhibitory mechanism of T cell activation may provide new approaches for HIV and immunoactivation therapy.

Keywords: HIV, GBV-C, T cell activation, TCR, Envelope glycoprotein

INTRODUCTION

GB virus C (GBV-C) is a human virus within the Flaviviridae that is related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1). Although GBV-C infection is common and about 2% of healthy U.S. blood donors have viremia at the time of donation, it is not associated with any disease (1,2). Due to shared routes of transmission, the rate of GBV-C infection is high among HIV-infected individuals, with a prevalence of up to 42% (2,3). GBV-C is lymphotropic, and virus particles are produced when lymphocytes from infected subjects are cultured ex vivo (4,5). Several clinical studies, including a meta-analysis of HIV-positive subjects found an association between persistent GBV-C infection and prolonged survival in HIV-infected individuals (6-10). Although several mechanisms have been proposed for this beneficial association between GBV-C coinfection and HIV-related survival(11), recent studies suggest that GBV-C reduces HIV-associated chronic immune activation, and that this contributes to better HIV clinical outcomes (5,12-17).

HIV infection is associated with chronic immunoactivation that contributes to HIV mediated immune dysfunction, and immune activation facilitates HIV replication and pathogenesis (18,19). Although combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) suppresses HIV plasma viral load (VL), the level of immune activation markers do not return to levels observed in HIV-uninfected individuals (20,21). In addition, persistent immune activation observed in HIV-treated individuals is associated with a reduced response to HIV therapy (22,23). Among HIV-infected subjects GBV-C coinfection is associated with reduced immune activation independent of HIV VL or cART (13,14,16), suggesting that GBV-C infection alters immune activation pathways. Since GBV-C replication in vitro is reduced by T cell activation (5), the development of mechanisms to inhibit immune activation is beneficial for the virus. Understanding mechanisms by which GBV-C reduces chronic immune activation in HIV-infected subjects may lead to novel approaches to treat HIV infection and HIV associated chronic immune activation. Here, we examined potential mechanisms by which GBV-C infection reduces immunoactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of GBV-C E2 protein

Tet-off Jurkat cell lines expressing GBV-C E2 protein (nt 1167-2161 based on GenBank AF 121950), the vector control (expressing GFP) and E2 coding sequence with a plus one frameshift mutation inserted to abolish protein expression (FS control) were previously described (12). Six truncated E2 proteins were ligated into a modified pTRE2-HGY plasmid (Clontech, Inc.) as described (24,25). This plasmid generates a bicistronic message encoding the GBV-C E2 sequence followed by the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMC) internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) that directs translation of GFP. Jurkat (tet-off) cell lines (Clontech, Inc) were transfected (Nucleofector II, Lonza Inc.) and cell lines selected for resistance to hygromycin and neomycin. GFP positive cells were bulk sorted using a BD FACS Diva (University of Iowa Flow Cytometry Facility). Protein expression was analyzed by measuring GFP by flow cytometry (BD LSR II) and by immunoblot using antibodies directed against a C-terminal histidine tag (Qiagen). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin with hygromycin and neomycin (200 μg/ml). Insert sequences were confirmed by sequencing plasmid DNA (University of Iowa DNA Core Facility).

Cell Stimulation

Jurkat cells (5×106 cells/ml) were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (5μg/ml, OKT3 clone, eBioscience) and soluble CD28 antibody (5 μg/ml, clone CD28.2, BD Biosciences) unless stated otherwise. For co-culture experiments, non-transfected GFP negative Jurkat cells (5×105 cells/ml) were incubated with either the transfected GFP positive vector control or GFP positive GBV-C E2 expressing cells (1×106 cells/ml) for 72 hours prior to stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28. Following 24 hours of stimulation, cellular receptor expression and cytokine release were measured by flow cytometry in GFP negative cells and by ELISA respectively.

Flow cytometry

Cellular receptor expression was measured with CD69 (PE), CD25 (APC), or CD45 (PE) (BD Biosciences) using the manufacturer's recommendation. Cells were incubated on ice for 1 hour, washed 3 times with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences). Data was acquired on BD LSR II flow cytometer using single stained CompBeads (BD Biosciences) for compensation. At least 10,000 total events were collected in each experiment and the FlowJo program (Tree Star Inc.) was used for data analysis. All flow cytometry experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

Immunoblot Analysis

Jurkat cells (5×106) were stimulated with anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) for the time indicated prior to addition of cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) for 15 minutes and sonication. Lysates were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BIORAD). Membranes were incubated in protein-free blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with primary antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with Amersham ECL (GE Healthcare) using a Kodak Imager. Protein phosphorylation was quantified using ImageJ (NIH) and normalized to total protein levels. Primary antibodies used were: pLAT(Y226; BD Biosciences); total LAT (Biolegend); CD63 antibodies (Systems Biosciences); and pZAP70 (Y319); total ZAP70; pLck (Y505); pLck (Y394/pSrcY416); total Lck (Y394) and total Csk (all from Cell Signaling Technology). For immune precipitation studies, Jurkat cell lysates were incubated with recombinant Fc fused GBV-C E2 protein (Bhattarai et al., 2012a), or GBV-C E2 expressing Jurkat cell lysates were incubated with anti-Lck antibodies overnight at 4°C as described. Protein complexes were isolated from the cellular lysates using protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Scientific) and precipitated proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis.

ELISA

IL-2 cytokine released into cell culture supernatant was quantified using human IL-2 quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Enzyme activity assays

CD45 activity was measured using CD45 tyrosine phosphatase assay kit (Enzo Life Sciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. Purified recombinant GBV-C E2 protein expressed in CHO cells was described previously (12). Enzymatic activity was evaluated with or without GBV-C E2 protein (10 μg) or human IgG control (10 μg; Sigma) at room temperature. Following 1-hour incubation, the reaction was terminated and absorbance determined by a Microplate reader (Model 680, Bio-Rad) at OD620nm. Phosphorylation of GBV-C E2 protein by Lck was measured by incubating recombinant E2 protein (40 μg) with or without human Lck (500 ng; R&D Systems) as recommended by the manufacturer. Samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described above. Phosphorylation was determined by immunoblot analysis with phosphotyrosine antibodies (Invitrogen) and GBV-C E2 protein was identified using an anti-E2 monoclonal antibody as described (2). Lck mediated phosphorylation of GBV-C E2 derived TAT-peptides were performed using Lck kinase enzyme system (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer.

GBV-C E2 synthetic peptides

FITC labelled synthetic peptides with an N-terminal HIV TAT protein transduction domain (TAT) alone (GGGGGRKKRRQRRR), or with the GBV-C E2 aa 86-101 (GGGGGRKKRRQRRRVYGSVSVTCVWGS; Y87), or the Y87H mutation (GGGGGRKKRRQRRRVHGSVSVTCVWGS) were purchased from Ana Spec, Inc. Peptides with the TAT domain and GBV-C E2 aa 276-292 (GGAGLTGGRYEPLVRRC), or the same amino acids in a scrambled order (GCRCARGVLLTPGEGYF) were previously described (25). Peptides were dissolved in RPMI with 10% DMSO. Healthy donor PBMCs (1×106 cells/ml) were incubated with 20μg peptide at 37°C over night before stimulation with 500ng/ml anti-CD3/CD28. IL-2 release and cellular receptor expression was analyzed 24 hrs later.

GBV-C RNA quantification

GBV-C viremic HIV-infected subjects receiving cART who were attending the University of Iowa HIV Clinic and healthy volunteer blood donors were invited to participate. HIV-infected subjects’ HIV viral load (VL) was below the limit of detection (<48 copies/mL) for a minimum of 6 months and at the time of blood donation. All subjects and healthy blood donors provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. PBMCs were prepared as described (5). For sorting experiments, CD3+ T cells were enriched using Automacs (Miltenyi Biotech), and CD3+ T cells were sorted into CD4+ and CD8+ populations by FACS (BD ARIA II) using CD3 (V450), CD4 (FITC), CD8 (Alexa700) antibodies (all BD Biosciences). Sorted cells were counted using Countess™ automated cell counter (Invitrogen). Total cellular RNA from specific T cell populations was isolated and GBV-C RNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR as described (5).

Extracellular Microvesicles (EMV) Isolation

EMV were purified from the clarified cell-culture supernatant or from human serum using the ExoQuick reagent (Systems Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This commercial reagent has been previously reported to yield EMV from cell culture supernatant and human serum (26-29). Sodium chloride (NaCl) density flotation was performed as described (30). Briefly, 1ml of undiluted serum was mixed with 35 ml of NaCl solution (1.063 g/ml), and centrifuged in a Beckman SW28 rotor (112,000 × g, 4°C × 65 hrs). Following centrifugation, fractions were collected for subsequent analysis. PBMCs from healthy donors were incubated with EMV purified from 5 ml of GBV-C positive or GBV-C negative serum or EMV purified from 10 ml of culture supernatant overnight and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (500 ng/ml) for 24 hours before analysis.

Statistics

Statistics were performed using GraphPad software V4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Two-sided Student's t test was used to compare results between GBV-C E2 protein expressing cells and controls. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Extracellular microvesicles from GBV-C infected human serum inhibit T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in primary human T cells

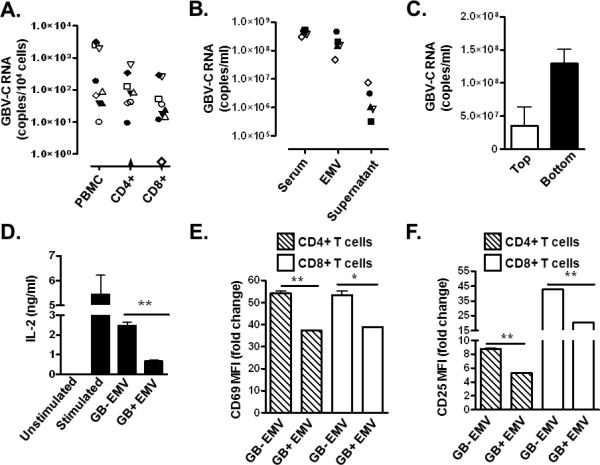

GBV-C infection is associated with global reduction in T cell activation and reduced IL-2 signaling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (5,13-17). Since the frequency of GBV-C infected lymphocytes in peripheral blood is unknown, GBV-C RNA copy number within CD4+ and CD8+ T cells obtained from nine GBV-C viremic subjects was determined. Using immunoaffinity selection and fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS), highly purified (>99%) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were recovered from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Supplemental Material Fig. 1). GBV-C RNA was detected in PBMCs obtained from all nine subjects with an average of 879 genome equivalents (G.E.) per 104 cells (Fig. 1A). Viral RNA was detected in both CD4+ T cells (average 146 GE per 104 cells) and CD8+ T cells (average 77 GE per 104 cells) in all but two subjects. One of these subjects had GBV-C RNA detected in CD4+ T cells while the other had GBV-C RNA present in only the CD8+ T cell population (Fig. 1A). If only one copy of GBV-C RNA is produced per cell, then less than 10% of PBMCs are infected. It is likely that infected cells contain multiple copies of viral RNA and thus the proportion of GBV-C infected PBMCs is much lower than 10%. Since clinical studies demonstrate global reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation in GBV-C infected subjects (13,15,16), GBV-C infection must alter T cell activation in uninfected T cells.

Figure 1. Extracellular microvesicles from GBV-C infected human serum inhibit T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in primary human T cells.

GBV-C RNA concentration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and in purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells obtained from nine GBV-C-infected subjects (A). GBV-C RNA concentration in serum, the extracellular microvesicle (EMV) pellet or supernatant purified from the serum of five GBV-C-infected individuals (B). GBV-C RNA concentration in the top and bottom fraction of serum separated using saline flotation gradient centrifugation (C). IL-2 release by PBMCs (D) and CD69 and CD25 cell surface expression (E, F) of PBMCs incubated with GBV-C positive (GB+) or negative (GB−) serum-derived EMV following activation with CD3 and CD28 antibodies. Fold change was calculated using CD69 and CD25 MFI levels before and after stimulation. MFI = mean fluorescence intensity. Data represent the average of three independent cultures, independently performed three times. *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01

The closely related hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmits viral RNA and proteins to bystander cells via extracellular microvesicles (31,32). The related GBV-C may employ a similar mechanism to interact with uninfected bystander cells. To test this hypothesis, extracellular microvesicles (EMV) purified from the sera of GBV-C viremic subjects were examined for GBV-C RNA. Serum EMV were purified using a commercial reagent (Exoquick), and more than 98% of serum GBV-C RNA was precipitated (Fig. 1B). Consistent with a previous study (30), saline flotation gradient centrifugation of GBV-C-positive serum yielded two populations of GBV-C RNA-containing particles with distinctly different densities. Viral RNA was concentrated in the low-density fraction (1.07 g/ml; Fig. 1C, Top), consistent with virions associated with LDL, and in a heavier fraction (~1.16 g/ml; Fig. 1C, Bottom). The density of the heavier particles was similar to that described for vesicles of endocytic origin (exosomes; 1.10-1.19 g/ml) (33) and were precipitated by the commercial exosome purification reagent (Exoquick). In contrast, the low density particles did not precipitate with Exoquick reagent, suggesting microvesicles of endocytic origin are preferentially precipitated by Exoquick reagent (data not shown). Primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy blood donors were incubated with EMV prepared from GBV-C viremic (GB+ EMV) or GBV-C non-viremic (GB−EMV) sera prior to TCR engagement with CD3/CD28 antibodies. GB+ EMV inhibited TCR-mediated signaling compared to GB− EMV as measured by the release of IL-2 into culture supernatants (Fig. 1D), or by cell surface expression of T cell activation markers (CD69 and CD25; Fig.1E-F).

These data demonstrate that GBV-C RNA containing microvesicles in the serum of infected subjects inhibited TCR signaling in uninfected T cells, providing a potential mechanism to explain the global reduction in T cell activation observed in humans with HIV-GBV-C coinfection.

GBV-C E2 protein inhibits TCR-mediated activation of CD4+ T cells

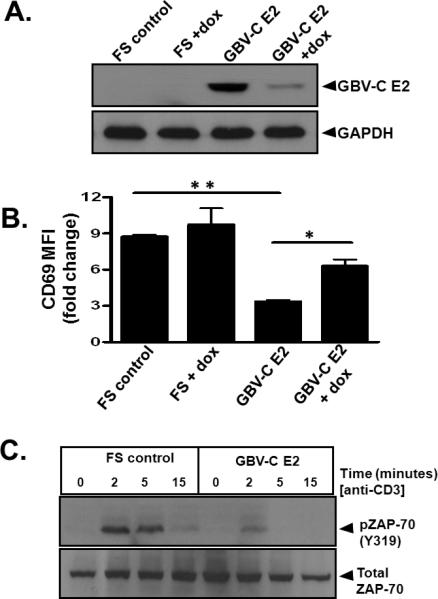

The GBV-C envelope glycoprotein E2 was previously shown to inhibit activation and IL-2 signaling pathways in human T cells (12). To determine if TCR activation was altered by E2 protein, E2 RNA or both, activation was measured in tet-off Jurkat (CD4+) T cells before and following TCR stimulation with CD3/CD28 antibodies. Tet-off Jurkat cells stably expressing GBV-C E2 protein or the GBV-C E2 coding sequence in which a plus one frame shift (FS) was inserted to abolish translation were incubated with or without doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 5 days to reduce transcription of the GBV-C E2 sequence (Fig. 2A). Activation following TCR stimulation, as measured by CD69 expression, was significantly inhibited in E2 expressing Jurkat cells compared to the control FS cells expressing the E2 RNA (Fig. 2B). Inhibition was significantly reversed in cells maintained in doxycycline (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. GBV-C E2 protein expression inhibits T cell receptor (TCR) mediated activation of CD4+ T cells.

Jurkat (tet-off) cells stably expressed GBV-C E2 protein or the same GBV-C sequence with a plus one frame shift to abolish translation (FS). Incubation with doxycycline (dox; 1 μg/ml) for 5 days significantly reduced E2 protein expression (A). Twenty four hours after TCR stimulation with CD3 and CD28 antibodies, CD69 surface expression was significantly reduced in Jurkat cells expressing E2 protein, and this was reversed by maintaining cells in doxycycline (B). Data represent the fold increase in CD69 expression before and after TCR stimulation from three independent cultures. *P< 0.05; **P< 0.001. Phosphorylation of the zeta-chain-associated protein kinase (ZAP)-70 (C) in GBV-C E2 expressing Jurkat cells compared to the frameshift control (FS) with TCR activation using anti-CD3. MFI= mean fluorescence intensity. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with consistent results.

Since GBV-C E2 protein expression inhibited activation following TCR stimulation, the effects of E2 protein on proximal TCR signaling pathways were assessed. Following TCR stimulation, phosphorylation of zeta-chain-associated protein kinase (ZAP)-70 (Fig. 2C) and the linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (data not shown) was reduced in GBV-C E2 expressing cells compared to the FS control. The reduction in phosphorylation was not due to differences in total cellular ZAP-70 (Fig. 2C) or LAT (data not shown) levels in the E2-expressing and FS control Jurkat cells. Thus, expression of GBV-C E2 protein and not the E2 coding RNA inhibited T cell activation by reducing the activation of proximal TCR signaling pathways.

GBV-C E2 protein inhibits Lck activation

Lymphocyte specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck) activation is required for signaling through the TCR (34). Inactive Lck is phosphorylated at tyrosine 505 (Y505) by the C-src tyrosine kinase (Csk). Following TCR engagement, phosphorylated Y505 is dephosphorylated by CD45 tyrosine phosphatase, leading to a change in conformation and subsequent auto-phosphorylation of Lck tyrosine 394 (Y394) in trans (34). Lck must be phosphorylated at Y394 to be active, leading to ZAP70 phosphorylation and downstream signaling through the TCR pathway.

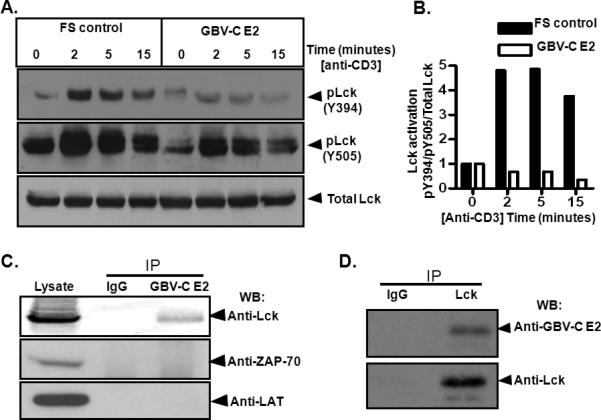

Following TCR engagement with anti-CD3, Lck activation was reduced in Jurkat cells expressing E2 protein compared to FS controls as measured by Y394 and Y505 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A-B). Lck Y394 phosphorylation was comparable at baseline in Jurkat cells expressing GBV-C E2 and FS control; however, Y505 phosphorylation was lower in GBV-C E2 expressing cells suggesting that E2 expression suppressed Y505 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). To determine if GBV-C E2 interacted directly with Lck, recombinant GBV-C E2 protein was incubated with Jurkat cell lysates. The E2 – cell lysates were incubated with Lck, ZAP-70 or LAT antibodies to precipitate these proteins. GBV-C E2 protein specifically co-precipitated Lck but not ZAP-70 or LAT (Fig. 3C). Consistent with this finding, pull down of GBV-C E2 from E2 expressing Jurkat cells also specifically precipitated Lck (Fig. 3D), thus the GBV-C E2 protein interacts with Lck, and inhibits Lck activation following TCR stimulation.

Figure 3. GBV-C E2 protein interacts with and inhibits Lck activation.

Phosphorylation of Lck Y394 in Jurkat cells expressing GBV-C E2 protein compared to the frameshift (FS) control following TCR stimulation with anti-CD3 by immunoblot (A). The data were quantified by densitometry (B). Following precipitation with protein A/G, Jurkat cell lysates incubated with recombinant GBV-C E2-human Fc fusion (E2-Fc) precipitated Lck but not Zap-70 or LAT, whereas addition of IgG to the lysates did not precipitate Lck (C). Similarly, Lck precipitation from E2 expressing Jurkat cells precipitated E2 protein (D). Each experiment was repeated at least three times with consistent results.

The inhibition in TCR-mediated activation of Lck was not due to altered Lck regulation, as the level of CD45 and Csk expression were similar on GBV-C E2 expressing Jurkat cells and on the FS control cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, CD45 phosphatase activity was not altered in vitro by incubation with recombinant GBV-C E2 protein (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

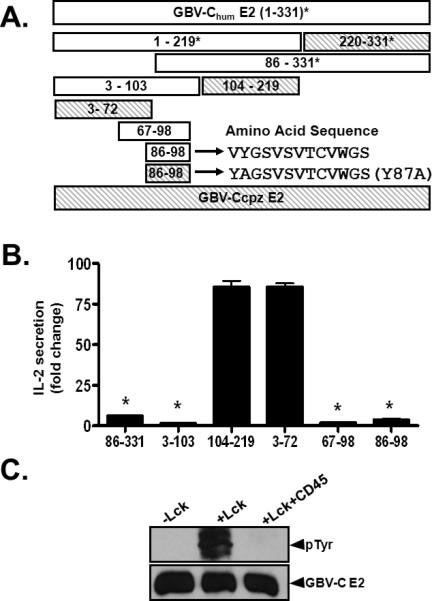

A 13 amino acid peptide domain within GBV-C E2 inhibits T cell receptor (TCR) signaling

Expression of the N-terminal region 219 aa of GBV-C E2 protein was sufficient to inhibit IL-2 production following TCR stimulation (12). To characterize the region(s) within the GBV-C E2 protein required for TCR signaling inhibition, Jurkat cells expressing truncated GBV-C E2 proteins were generated (Fig. 4A). All cell lines stably expressed GFP detected by flow cytometry (Supplemental Material Fig. 3). Following TCR stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28, IL-2 production was blocked in all of the cell lines that contained a 13 amino acid motif within GBV-C E2 (aa 86-98), but not in cell lines that expressed other regions of the E2 protein (Fig. 4B). Based on kinase-specific phosphorylation substrate prediction programs, the tyrosine residue at position 87 (Y87) in GBV-C E2 is predicted to be an Lck (Src-kinase) target (Fig. 4A; references 35, 36). Although the kinase substrate prediction required the sequence of E2 to begin at position 83, the 13mer peptide sequence (86-98 aa) contains upstream vector amino acid sequences which maintain the site as a predicted Lck substrate. Consistent with this, recombinant Lck phosphorylated recombinant E2 in an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4C). Similar to Lck, the GBV-C E2 protein was dephosphorylated by CD45 tyrosine phosphatase (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Characterization of a peptide domain within GBV-C E2 that inhibits T cell receptor (TCR) signaling.

Panel A illustrates Jurkat cells lines generated that stably expressed GBV-C E2 proteins (amino acid numbers shown). * = previously described cell lines. Cell lines that did not inhibit TCR signaling are shaded (A). IL-2 release following TCR stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 is shown for cell lines expressing various E2 amino acids (B). Fold change in IL-2 release was calculated by measuring IL-2 at baseline (~5 pg/ml) and after anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation for 24 hours. Recombinant E2 protein was phosphorylated by Lck in an in vitro kinase reaction (C), and was dephosphorylated by the CD45 phosphatase (C). Data represents average from three independent cultures, independently performed three times. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with consistent results. *P<0.01.

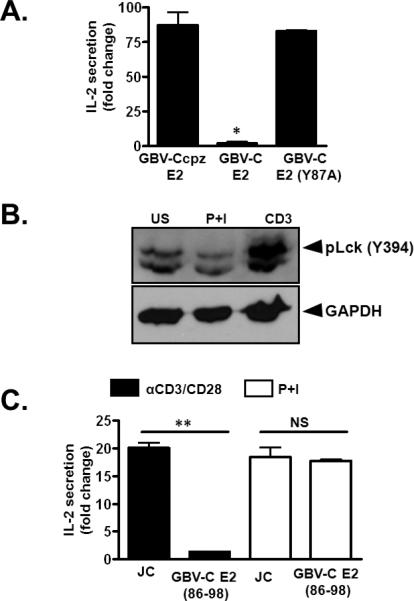

The predicted Lck substrate motif within GBV-C E2 (aa 83-91; PQYVYGSVS) is highly conserved among GBV-C isolates. There is complete homology among 39 of 42 published human GBV-C isolates representing all seven GBV-C genotypes (Supplemental Material Fig. 4A). The three isolates that differed had only a single aa difference (Q84L or V90A), and these polymorphisms maintained a predicted Lck phosphorylation site. In contrast, this E2 protein sequence in chimpanzee GBV-C variant isolates (GBV-Ccpz) differed significantly (PRYVHGHIT; Supplemental Material Fig. 4A). The GBV-Ccpz E2 protein has a histidine residue at position 87 (H87) instead of a tyrosine, and this sequence is not predicted to be phosphorylated by Lck. Consistent with this, expression of the GBV-Ccpz E2 protein in Jurkat cells did not inhibit IL-2 production following TCR stimulation (Fig. 5A), and expression of the human GBV-C E2 peptide motif with a tyrosine to alanine substitution at aa 87 (Y87A) did not inhibit TCR signaling (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. GBV-C E2 protein specifically inhibits TCR signaling via Lck activation.

IL-2 release in Jurkat cells expressing the chimpanzee GBV-C E2 protein (GBV-Ccpz E2), the human GBV-C E2 protein, or the human GBV-C protein with an alanine substitution for tyrosine (GBV-C E2 Y87A) following anti-CD3/CD8 (A). Lck activation following incubation with PMA (50 ng/ml) and Ionomycin (1μg/ml) (P+I) or anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) for 2 minutes compared to unstimulated Jurkat cells (US; panel B). Fold-change in IL-2 release by Jurkat cell control (JC) or cells expressing GBV-C E2 following 24 hr incubation in anti-CD3 or PMA (50 ng/ml) plus Ionomycin (1 μg/ml) (P+I) (C). Data represents average from three independent cultures. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with consistent results. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

There is a second predicted Lck phosphorylation substrate motif that is also highly conserved within the GBV-C E2 protein (aa 281-289, TGGFYEPLV; Supplemental Material Fig. 4B). Previous studies and additional mapping expressing E2 proteins in Jurkat cells (Fig. 4A) demonstrated that this region of E2 does not inhibit TCR-mediated activation (12) (Fig. 4B). GBV-C E2 protein also contains two well-conserved Src homology domain 3 (SH3) binding domains (PXXP; aa 48-51 and 257-260; Supplemental Material Fig. 4C-D) (37,38). Neither of these regions was required for inhibition of TCR-signaling (Fig. 4A-B) (12).

To determine if the effect of GBV-C E2 protein on activation was specific for TCR-mediated signaling, control Jurkat cells or Jurkat cells expressing the human GBV-C E2 (86-98 aa) were stimulated with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin, which bypass the TCR for activation of T cells. Incubation of Jurkat cells in PMA-ionomycin did not activate Lck (Fig. 5B), and the GBV-C E2 peptide (86-98) did not inhibit IL-2 release in PMA-ionomycin-stimulated cells (Fig. 5C).

Thus, a highly conserved region within the GBV-C E2 protein contains a predicted Lck substrate motif, and expression of this region in CD4+ T cells inhibited TCR-mediated signaling. GBV-C E2 protein did not inhibit activation of T cells through non-TCR pathways (PMA-ionomycin).

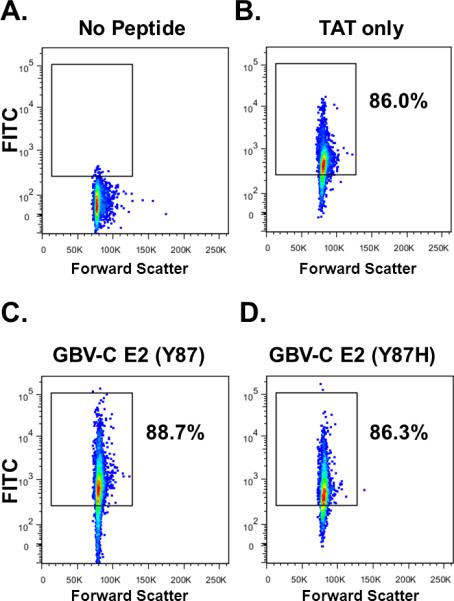

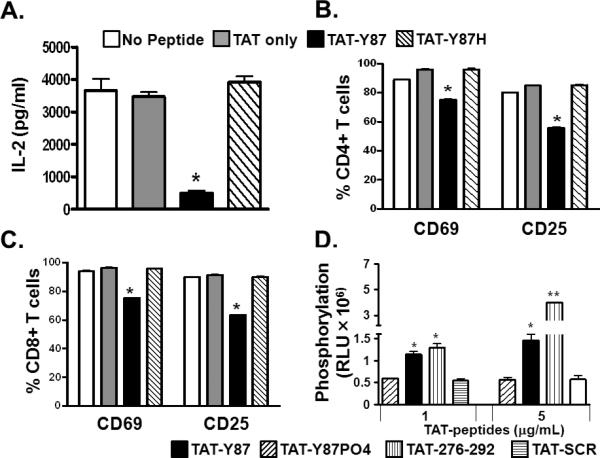

Synthetic GBV-C E2 peptides inhibit TCR activation in primary human T cells

To confirm that the predicted Lck substrate motif within GBV-C E2 protein was sufficient to inhibit TCR-mediated signaling in primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, synthetic peptides with the native sequence (aa 86-101), or with a histidine substituted for the tyrosine at aa 87 (Y87H) were generated and tested for their abilities to inhibit TCR-mediated activation. The peptides were biotinylated to monitor cellular uptake, and included an N-terminal HIV Tat protein transduction domain (TAT) to promote internalization by target cells. A TAT only synthetic peptide served as a negative control. All three biotinylated peptides were internalized by healthy human PBMCs as demonstrated by flow cytometry (Fig. 6). Following TCR stimulation, IL-2 production by PBMCs was inhibited in cells incubated with the TAT-Y87 peptide, but not in those incubated with either the TAT-Y87H or the TAT control peptides (Fig. 7A). Similarly, surface expression of T cell activation markers CD69 and CD25 was significantly reduced in primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells incubated with the TAT-Y87 peptide compared to mutant or control peptide (Fig. 7B-C).

Figure 6. Uptake of TAT-fused peptides in PBMCs.

Flow cytometry analysis of PBMCs following 24 hour incubation with FITC-labelled synthetic peptides. No peptide control (A), control peptides with an HIV TAT protein transduction domain sequence at the N-terminus (TAT-only) (B), peptides representing GBV-C aa 86-98 (Y87) with TAT (C), and the same sequence with a histidine substitution for tyrosine (Y87H) (D). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate and repeated on a separate day with consistent results.

Figure 7. Synthetic GBV-C E2 peptides inhibit TCR activation in primary human T cells.

IL-2 release (A) from primary human PBMCs, and cell surface CD69 and CD25 expression on primary human CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (C) T cells following TCR-stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28. Cells were incubated in synthetic peptides with an N-terminal HIV TAT protein transduction domain including the native GBV-C E2 86-101 sequence (TAT-Y87), the same sequence with a histidine substitution for Y87 (TAT-Y87H), the TAT sequence alone (TAT-only), or with no peptide. Lck-mediated phosphorylation of synthetic peptides including the GBV-C amino acid 276-292 sequence (TAT-276-292), the TAT-Y87 peptide synthetically phosphorylated (TAT-Y87PO4) or the 276-292 peptide amino acids synthesized in a scrambled order TAT-SCR (D). RLU= relative luminescence units. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with consistent results. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

The TAT-Y87 peptide was phosphorylated by Lck in a dose-dependent manner in an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 7D); however, a synthetically phosphorylated Y87 peptide (TAT-Y87PO4) did not serve as an Lck substrate (Fig. 7D). Thus, this peptide serves as an Lck substrate and will compete for phosphorylation with Lck. As noted, there is a second predicted Lck substrate motif within GBV-C E2 (aa 281-289) that did not inhibit TCR-mediated IL-2 production (12). However, the synthetic peptide containing this motif (TAT-276-292) served as an in vitro Lck substrate (Fig. 7D) while a control peptide with the same E2 amino acids (aa 281-289) synthesized in a scrambled order (TAT-SCR) was not phosphorylated by Lck in vitro (Fig. 7D).

Together, these data demonstrate that synthetic peptides representing Lck substrate motifs within GBV-C E2 protein are phosphorylated by Lck and inhibit TCR signaling in human T cells.

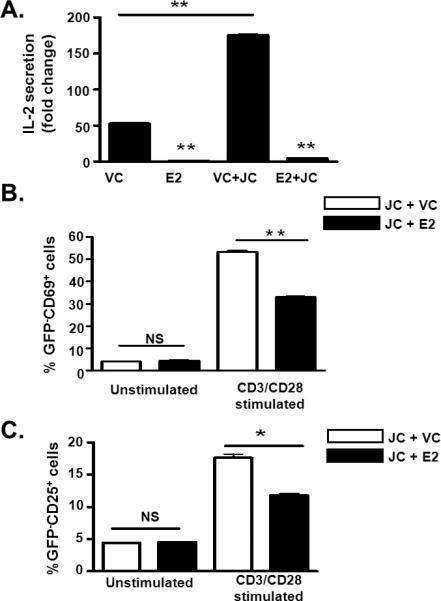

GBV-C E2 protein inhibits T cell activation in bystander cells

Since GBV-C E2 protein expression inhibited TCR signaling (Fig. 2), we hypothesized that E2 expressing cells may inhibit TCR signaling in bystander cells contributing to global reduction in TCR signaling that has been observed in GBV-C infected subjects (13,14,16,17). To test this hypothesis, GBV-C E2 expressing (GFP positive) or vector control Jurkat cells (VC; also GFP positive) were co-cultured with Jurkat cells not expressing GFP. Following TCR engagement, IL-2 secretion (Fig. 8A) and surface expression of the activation markers CD69 and CD25 (Fig. 8B and 8C) were significantly inhibited in the bystander Jurkat cells co-cultured with GBV-C E2 expressing cells compared to bystander cells co-cultured with the vector control cells. Since serum extracellular microvesicles (EMV) from GBV-C infected subjects inhibited TCR signaling when incubated with primary human T cells (Fig. 1), we examined Jurkat cell supernatants for EMV. GBV-C E2 protein was detected in EMV purified from E2-expressing Jurkat cell culture supernatant but not in EMV from the FS supernatant fluid (Fig. 8D). Both E2-expressing and the FS expressing Jurkat cells released EMV that contained CD63 (Fig. 8D), supporting an endocytic origin (33), and consistent with the findings of EMV present in GBV-C infected human serum (Fig. 1B-C).

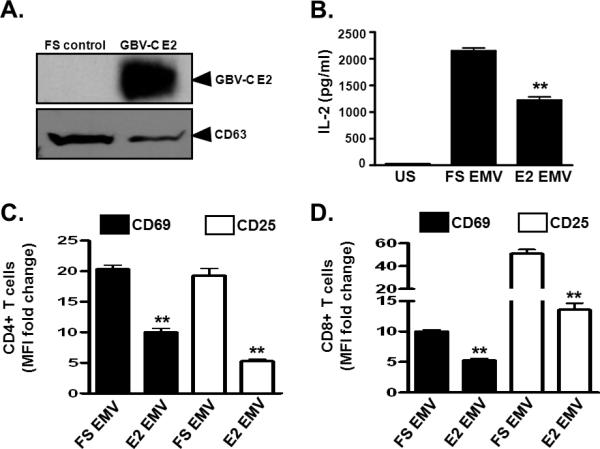

Figure 8. GBV-C E2 protein inhibits T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in bystander cells.

IL-2 release by (A), and surface expression of CD69 (B) and CD25 (C) on parental Jurkat cells (JC; GFP negative) following TCR stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28. Cells were co-cultured with GBV-C E2 expressing cells (GFP positive) or with vector control cells (VC; GFP positive). Data represent the average of three independent cultures. *P<0.01, **P<0.01.

To determine if GBV-C E2 protein released from Jurkat cells reduced TCR signaling in bystander T cells, primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy blood donors were incubated with EMV purified from E2-expressing Jurkat cells (E2 EMV) or FS control Jurkat cells (FS EMV). Following TCR engagement, IL-2 release (Fig. 9A) and cell surface expression of CD69 and CD25 (Fig. 9B-C) were significantly reduced in cells incubated with E2 EMV compared to cells incubated with FS EMV.

Figure 9. GBV-C E2 protein in extracellular microvesicles (EMV) inhibit T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in primary CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Detection of GBV-C E2 protein and CD63 in extracellular microvesicles (EMV) purified from cell culture supernatants (see methods) of Jurkat cells expressing GBV-C E2 protein or the frameshift control (FS) (A). Following TCR stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28, IL-2 release (B), CD69 and CD25 cell surface expression (C, D) in PBMCs obtained from healthy, GBV-C negative donors. Cells were incubated with GBV-C E2 positive extracellular vesicles (E2 EV) or GBV-C negative microvesicles (FS EV). Fold change was calculated by measuring IL-2, CD69 and CD25 levels before and after stimulation. US=unstimulated, MFI= mean fluorescence intensity. Data represent the average of three independent cultures. *P<0.01, **P<0.01.

Thus the GBV-C E2 protein expressing cells inhibited TCR signaling in bystander T cells, and GBV-C E2 protein released from Jurkat cells was contained within EMV. The GBV-C E2-containing EMV inhibited TCR signaling in bystander T cells.

DISCUSSION

GBV-C and the related HCV are the only two cytoplasmic RNA viruses that commonly cause persistent human infection. Among HIV-infected people, persistent GBV-C co-infection is associated with prolonged survival, reduced T cell activation and altered IL-2 signaling (5,12-14,16,17). The IL-2 signaling defect is due, at least in part, to inhibition of TCR signaling by the envelope glycoprotein E2 (12) and these T cell activation and IL-2 signaling effects may contribute to viral persistence (11). In addition, antibodies to GBV-C proteins are usually not detected during viremia, suggesting an impairment in B cell function (1). This may also reflect altered antigen presentation.

Although there is an association between GBV-C infection and reduced levels of global T cell activation (13,14,16), only a small proportion of T cells contained viral genomes. Thus, virus and viral components present in virions, extracellular microvesicles, or virus-infected cells must interact with and inhibit activation of uninfected bystander T cells. We show that extracellular microvesicles present in sera obtained from GBV-C infected subjects, and released by E2-expressing Jurkat cells inhibited TCR signaling in bystander primary human T cells. This is accomplished by reducing the activation of Lck, the proximal tyrosine kinase phosphorylated in the TCR signaling cascade. The data are consistent with the transfer of GBV-C E2 protein within virus particles or in EMV to bystander cells with resultant TCR-signaling inhibition. Since the average GBV-C RNA concentration in infected humans is greater than 1 × 107 genome copies/mL of plasma, and the virus is produced by T cells (5), lymphoid tissue is constantly exposed to high concentrations of GBV-C E2 protein in infected humans.

Synthetic peptides containing only one of the two predicted Lck substrate motifs on GBV-C E2 protein inhibited TCR signaling in the CD4+ T cell line and in primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Y87). Although the tyrosine at aa 285 was phosphorylated by Lck in vitro, this region of E2 did not inhibit TCR-mediated activation. This may reflect a lack of access of this E2 region to Lck, as the Y285 is not predicted to be the surface of the protein based on structural models of the related HCV E2 (39). This also suggests that not all predicted tyrosine kinase substrate motifs on viral structural proteins would display functional activity. GBV-C E2 protein bound to Lck in reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation experiments, most likely through interactions between SH3 binding domains on the GBV-C E2 protein and the SH3 domain on Lck. Although the SH3 binding regions were not required for TCR signaling inhibition, it is possible that either of these SH3 binding domains may contribute to Lck inhibition in the setting of natural infection. Although, Lck (Y394) phosphorylation was reduced in E2 expressing T cells, GBV-C E2 protein was phosphorylated by Lck in vitro. This suggests that E2 Y87 phosphorylation competes with Lck Y394 for autophosphorylation by Lck during GBV-C infection, and trans autophosphorylation of Lck Y394 is required for T cell activation through the TCR.

The E2 Lck substrate motif (aa 83-91) that inhibited TCR signaling is highly conserved in human GBV-C (GBV-Chum) isolates, but is absent in chimpanzee GBV-C (GBV-Ccpz) isolates. Expression of GBV-Ccpz E2 protein did not inhibit TCR signaling. This observation raises the possibility that T cell activation inhibition is not important for GBV-Ccpz. Since the immune reactivity of chimpanzee lymphocytes is significantly lower than that of human lymphocytes (40), it is tempting to speculate that there is less selective pressure for GBV-Ccpz to acquire TCR signaling inhibition mechanisms.

The specificity of E2 protein for TCR-signaling was confirmed, as substitution of alanine or histidine for Y87 abolished the TCR-signaling inhibition, and activation through non-TCR-mediated pathways was not inhibited. Both E2 protein and the peptide served as substrates for Lck-mediated phosphorylation in vitro. GBV-C E2 protein inhibited TCR-mediated activation but not PMA/ionomycin activation, and TCR signaling was reduced, and not completely inhibited by GBV-C E2. Thus, although GBV-C infection reduces global T cell activation, it does not completely block TCR-signaling in bystander cells. If it did, this would be disadvantageous, as it would create a state of severe immune suppression and clinical disease (11).

In summary, the GBV-C structural protein E2 inhibits TCR-mediated T cell activation by interacting with Lck and competing for Lck phosphorylation. The inhibition is mediated either by the expression of GBV-C E2 protein within cells, or by the transfer of E2 to bystander cells either in the virion or within serum microvesicular particles. These data identify a novel mechanism by which a viral structural protein interferes with tyrosine kinase function resulting in global inhibition of T cell activation.

A recent study using an unbiased approach identified interactions between 70 viral proteins (from 30 different viruses) and 579 host cell proteins from various cell lines. More than half of the host proteins interacting with viral proteins are involved in signal transduction pathways (41). Since there are numerous predicted kinase binding and substrate sites encoded in viral structural proteins, it is tempting to speculate that the mechanism by which GBV-C inhibits Lck may apply to other host cell signaling processes, and illustrates the potential for regulation of host cell function in noninfected cells by interactions with virus particles. These interactions may influence viral persistence and viral pathogenesis. Identification of the interactions between viral structural proteins and host cells may facilitate the design of novel and specific antiviral therapies and vaccines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our patients for participating in the research, Dr. Jon Houtman for helpful discussions, Wendy Sauter for assistance collecting clinical samples, and Drs. Jon Houtman, Stanley Perlman, John Harty, Fayyaz Sutterwala, and William Nauseef for critical review of the manuscript. We also thank the University of Iowa Flow cytometry core for assistance with cell sorting.

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (Merit Review Grants, JTS and JX), the National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI-58740, JTS), and the International Fulbright Science and Technology Award (ETC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Drs. Xiang, McLinden, Stapleton, and Mr. Bhattarai have patents or provisional patents related to the use of GBV-C as potential therapy for HIV. The authors have no additional financial interests. This potential conflict does not interfere with the Journal of Immunology requirement of free exchange of any materials used in studies published by the Journal and as recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stapleton JT, Foung S, Muerhoff AS, Bukh J, Simmonds P. The GB viruses: a review and proposed classification of GBV-A, GBV-C (HGV), and GBV-D in genus Pegivirus within the family Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:233–246. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.027490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohr EL, Xiang J, McLinden JH, Kaufman TM, Chang Q, Montefiori DC, Klinzman D, Stapleton JT. GB virus type C envelope protein E2 elicits antibodies that react with a cellular antigen on HIV-1 particles and neutralize diverse HIV-1 isolates. J Immunol. 2010;185:4496–4505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rey D, Vidinic-Moularde J, Meyer P, Schmitt C, Fritsch S, Lang JM, Stoll-Keller F. High prevalence of GB virus C/hepatitis G virus RNA and antibodies in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:721–724. doi: 10.1007/s100960000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George SL, Varmaz D, Stapleton JT. GB virus C replicates in primary T and B lymphocytes. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:451–454. doi: 10.1086/499435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rydze RT, Bhattarai N, Stapleton JT. GB virus C infection is associated with a reduced rate of reactivation of latent HIV and protection against activation-induced T-cell death. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:1271–1279. doi: 10.3851/IMP2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunnari G, Nigro L, Palermo F, Attanasio M, Berger A, Doerr HW, Pomerantz RJ, Cacopardo B. Slower progression of HIV-1 infection in persons with GB virus C co-infection correlates with an intact T-helper 1 cytokine profile. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:26–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-1-200307010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tillmann HL, Heiken H, Knapik-Botor A, Heringlake S, Ockenga J, Wilber JC, Goergen B, Detmer J, McMorrow M, Stoll M, Schmidt RE, Manns MP. Infection with GB virus C and reduced mortality among HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:715–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams CF, Klinzman D, Yamashita TE, Xiang J, Polgreen PM, Rinaldo C, Liu C, Phair J, Margolick JB, Zdunek D, Hess G, Stapleton JT. Persistent GB virus C infection and survival in HIV-infected men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:981–990. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang J, Wunschmann S, Diekema DJ, Klinzman D, Patrick KD, George SL, Stapleton JT. Effect of coinfection with GB virus C on survival among patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Chaloner K, Tillmann HL, Williams CF, Stapleton JT. Effect of early and late GB virus C viraemia on survival of HIV-infected individuals: a meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2006;7:173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattarai N, Stapleton JT. GB virus C: the good boy virus? Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J, Kaufman TM, Stapleton JT. GB virus C envelope protein E2 inhibits TCR-induced IL-2 production and alters IL-2-signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2012a;189:2211–2216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattarai N, Rydze RT, Chivero ET, Stapleton JT. GB Virus C Viremia Is Associated With Higher Levels of Double-Negative T Cells and Lower T-Cell Activation in HIV-Infected Individuals Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2012b;206:1469–1472. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maidana-Giret MT, Silva TM, Sauer MM, Tomiyama H, Levi JE, Bassichetto KC, Nishiya A, Diaz RS, Sabino EC, Palacios R, Kallas EG. GB virus type C infection modulates T-cell activation independently of HIV-1 viral load. AIDS. 2009;23:2277–2287. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d7a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarze-Zander C, Neibecker M, Othman S, Tural C, Clotet B, Blackard JT, Kupfer B, Luechters G, Chung RT, Rockstroh JK, Spengler U. GB virus C coinfection in advanced HIV type-1 disease is associated with low CCR5 and CXCR4 surface expression on CD4(+) T-cells. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:745–752. doi: 10.3851/IMP1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stapleton JT, Chaloner K, Martenson JA, Zhang J, Klinzman D, Xiang J, Sauter W, Desai SN, Landay A. GB Virus C Infection Is Associated with Altered Lymphocyte Subset Distribution and Reduced T Cell Activation and Proliferation in HIV-Infected Individuals. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stapleton JT, Chaloner K, Zhang J, Klinzman D, Souza IE, Xiang J, Landay A, Fahey J, Pollard R, Mitsuyasu R. GBV-C viremia is associated with reduced CD4 expansion in HIV-infected people receiving HAART and interleukin-2 therapy. AIDS. 2009;23:605–610. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831f1b00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE, Picker LJ. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat Med. 2006;12:289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazenberg MD, Otto SA, van Benthem BH, Roos MT, Coutinho RA, Lange JM, Hamann D, Prins M, Miedema F. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2003;17:1881–1888. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt PW, Brenchley J, Sinclair E, McCune JM, Roland M, Page-Shafer K, Hsue P, Emu B, Krone M, Lampiris H, Douek D, Martin JN, Deeks SG. Relationship between T cell activation and CD4+ T cell count in HIV-seropositive individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:126–133. doi: 10.1086/524143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinikoor MJ, Cope A, Gay CL, Ferrari G, McGee KS, Kuruc JD, Lennox JL, Margolis DM, Hicks CB, Eron JJ. Antiretroviral therapy initiated during acute HIV infection fails to prevent persistent T cell activation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318285cd33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deeks SG, Kitchen CM, Liu L, Guo H, Gascon R, Narvaez AB, Hunt P, Martin JN, Kahn JO, Levy J, McGrath MS, Hecht FM. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104:942–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, Bredt B, Hagos E, Lampiris H, Deeks SG. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1534–1543. doi: 10.1086/374786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang J, McLinden JH, Chang Q, Kaufman TM, Stapleton JT. An 85 amino acid segment of the GB Virus type C NS5A phosphoprotein inhibits HIV-1 replication in CD4+ Jurkat T-cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15570–15575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604728103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiang J, McLinden JH, Kaufman TM, Mohr EL, Bhattarai N, Chang Q, Stapleton JT. Characterization of a peptide domain within the GB virus C envelope glycoprotein (E2) that inhibits HIV replication. Virology. 2012;430:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bala S, Petrasek J, Mundkur S, Catalano D, Levin I, Ward J, Alao H, Kodys K, Szabo G. Circulating microRNAs in exosomes indicate hepatocyte injury and inflammation in alcoholic, drug-induced, and inflammatory liver diseases. Hepatology. 2012;56:1946–1957. doi: 10.1002/hep.25873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, Lovat F, Fadda P, Mao C, Nuovo GJ, Zanesi N, Crawford M, Ozer GH, Wernicke D, Alder H, Caligiuri MA, Nana-Sinkam P, Perrotti D, Croce CM. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2110–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh PP, Smith VL, Karakousis PC, Schorey JS. Exosomes isolated from mycobacteria-infected mice or cultured macrophages can recruit and activate immune cells in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;189:777–785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuang G, Wu X, Jiang Z, Kasman I, Yao J, Guan Y, Oeh J, Modrusan Z, Bais C, Sampath D, Ferrara N. Tumour-secreted miR-9 promotes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis by activating the JAK-STAT pathway. Embo J. 2012;31:3513–3523. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang J, Klinzman D, McLinden J, Schmidt WN, LaBrecque DR, Gish R, Stapleton JT. Characterization of hepatitis G virus (GB-C virus) particles: evidence for a nucleocapsid and expression of sequences upstream of the E1 protein. J Virol. 1998;72:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2738-2744.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreux M, Garaigorta U, Boyd B, Decembre E, Chung J, Whitten-Bauer C, Wieland S, Chisari FV. Short-range exosomal transfer of viral RNA from infected cells to plasmacytoid dendritic cells triggers innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masciopinto F, Giovani C, Campagnoli S, Galli-Stampino L, Colombatto P, Brunetto M, Yen TS, Houghton M, Pileri P, Abrignani S. Association of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins with exosomes. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2834–2842. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meckes DG, Jr., Raab-Traub N. Microvesicles and viral infection. J Virol. 2011;85:12844–12854. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05853-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis SJ, van der Merwe PA. Lck and the nature of the T cell receptor trigger. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Scansite 2.0: Proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue Y, Ren J, Gao X, Jin C, Wen L, Yao X. GPS 2.0, a tool to predict kinase-specific phosphorylation sites in hierarchy. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1598–1608. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700574-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandropoulos K, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Proline-rich sequences that bind to Src homology 3 domains with individual specificities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3110–3114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saksela K, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in HIV-1 Nef bind to SH3 domains of a subset of Src kinases and are required for the enhanced growth of Nef+ viruses but not for down-regulation of CD4. Embo J. 1995;14:484–491. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krey T, d'Alayer J, Kikuti CM, Saulnier A, Damier-Piolle L, Petitpas I, Johansson DX, Tawar RG, Baron B, Robert B, England P, Persson MA, Martin A, Rey FA. The disulfide bonds in glycoprotein E2 of hepatitis C virus reveal the tertiary organization of the molecule. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000762. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soto PC, Stein LL, Hurtado-Ziola N, Hedrick SM, Varki A. Relative over-reactivity of human versus chimpanzee lymphocytes: implications for the human diseases associated with immune activation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4185–4195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pichlmair A, Kandasamy K, Alvisi G, Mulhern O, Sacco R, Habjan M, Binder M, Stefanovic A, Eberle CA, Goncalves A, Burckstummer T, Muller AC, Fauster A, Holze C, Lindsten K, Goodbourn S, Kochs G, Weber F, Bartenschlager R, Bowie AG, Bennett KL, Colinge J, Superti-Furga G. Viral immune modulators perturb the human molecular network by common and unique strategies. Nature. 2012;487:486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature11289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.