Abstract

Acetylacetone dioxygenase (Dke1) is a bacterial enzyme that catalyzes the dioxygen-dependent degradation of β-dicarbonyl compounds. The Dke1 active site contains a nonheme monoiron(II) center facially ligated by three histidine residues (the 3His triad); coordination of the substrate in a bidentate manner provides a five-coordinate site for O2 binding. Recently, we published the synthesis and characterization of a series of ferrous β-diketonato complexes that faithfully mimic the enzyme-substrate intermediate of Dke1 (Park, H.; Baus, J.S.; Lindeman, S.V.; Fiedler, A.T. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11978–11989). The 3His triad was modeled with three different facially coordinating N3 supporting ligands, and substituted β-diketonates (acacX) with varying steric and electronic properties were employed. Here, we describe the reactivity of our Dke1 models toward O2 and its surrogate nitric oxide (NO), and report the synthesis of three new Fe(II) complexes featuring the anions of dialkyl malonates. Exposure of [Fe(Me2Tp)(acacX)] complexes (where R2Tp = hydrotris(pyrazol-1-yl)borate with R-groups at the 3- and 5-positions of the pyrazole rings) to O2 at −70 °C in toluene results in irreversible formation of green chromophores (λmax ~750 nm) that decay at temperatures above −60 °C. Spectroscopic and computational analyses suggest that these intermediates contain a diiron(III) unit bridged by a trans µ-1,2-peroxo ligand. The green chromophore is not observed with analogous complexes featuring Ph2Tp and PhTIP ligands (where PhTIP = tris(2-phenylimidazoly-4-yl)phosphine), since the steric bulk of the phenyl substituents prevents formation of dinuclear species. While these complexes are largely inert toward O2, Ph2Tp-based complexes with dialkyl malonate anions exhibit dioxygenase activity and thus serve as functional Dke1 models. The Fe/acacX complexes all react readily with NO to yield highspin (S = 3/2) {FeNO}7 adducts that were characterized with crystallographic, spectroscopic, and computational methods. Collectively, the results presented here enhance our understanding of the chemical factors involved in the oxidation of aliphatic substrates by nonheme iron dioxygenases.

1. INTRODUCTION

The oxidative cleavage of carbon-carbon bonds by mononuclear nonheme iron dioxygenases is a crucial step in the microbial degradation of many organic pollutants.1 Wellstudied examples include the intradiol and extradiol catechol dioxygenases,2 (homo)gentisate dioxygenases,3 and (chloro)-hydroquinone dioxygenases.4 In 2003, Straganz and co-workers demonstrated that a strain of Acinetobacter johnsonii is able to use acetylacetone—a toxic pollutant—as its sole source of carbon.5 The initial step of this process is performed by the enzyme acetylacetone dioxygenase (also known as β-diketone dioxygenase, Dke1), which uses O2 to convert acetylacetone to acetic acid and 2-oxopropanal. Biochemical and crystallographic studies revealed that the Dke1 active site contains a monoiron(II) center facially ligated by three histidine (3His) residues, a deviation from the 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad normally employed by nonheme iron dioxygenases.6 Dke1 is capable of oxidizing β-diketones and β-ketoesters with a variety of substituents at the 1-, 3-, and 5-positions; in each case, the substrate coordinates to Fe as the deprotonated acac-type anion.7 Initial mechanistic studies suggested that O2 reacts with the bound acac ligand in a concerted two-electron process, resulting in a peroxidate intermediate without direct involvement of the Fe center.8 However, in a subsequent computational study, Solomon and Straganz have set forth an alternative mechanism that involves formation of an Fe/O2 adduct prior to substrate oxidation.9

Dke1 has attracted the interest of synthetic inorganic chemists because of the presence of the unusual 3His triad in the active site, as well as the enzyme’s ability to catalyze aliphatic C–C bond cleavage. Interestingly, the first relevant model system was reported a decade before the discovery of Dke1. In 1993, Kitajima and co-workers generated the complex [Fe2+(iPr2Tp)(acac)(MeCN)] (where R2Tp = hydrotris-(pyrazol-1-yl)borate with R-groups at the 3- and 5-positions of the pyrazole rings).10 Exposure to O2 in MeCN at room temperature eventually produced crystals of the triiron(III) complex [Fe3(µ-O)(µ-OH)(µ-OAc)4(iPr2Tp)2], where the bridging acetate ligands derive from the acac group of the ferrous precursor. Thus, this synthetic model exhibits Dke1-type reactivity, although generation of the acetate ligands may proceed via a different mechanism than the one employed by the enzyme. In 2008, Limberg and Siewert demonstrated that the related complex, [Fe2+(Me2Tp)(acacPhmal)] (acacPhmal = anion of diethyl phenylmalonate), reacts with O2 to give Dke1-type products with incorporation of oxygen atoms from O2.11 The activated diethyl malonate anion was used because the corresponding acac complex failed to exhibit oxidative cleavage. Significantly, the [Fe2+(Me2Tp)(acacPhmal)] system is catalytic in the presence of excess Li(acacPhmal) and O2 with a turnover frequency of 55 h−1.

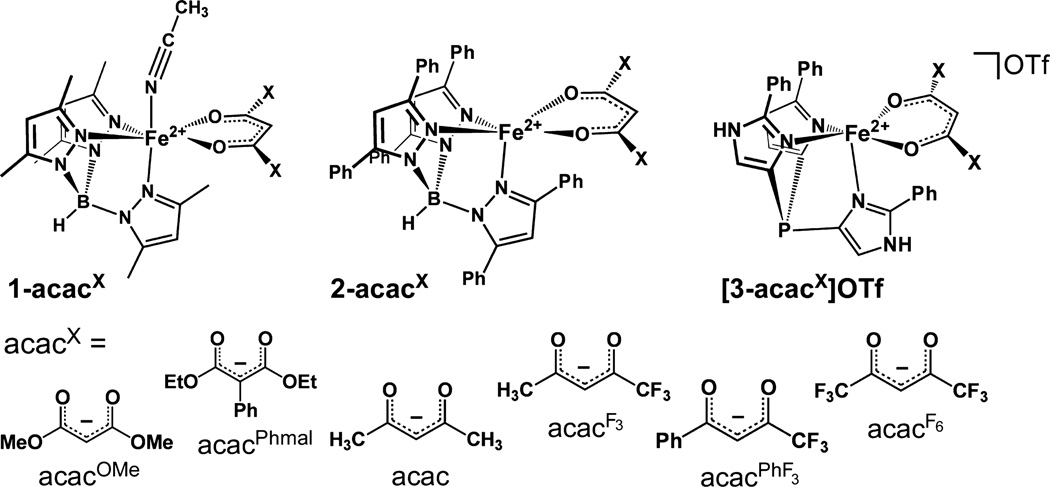

Recently, our group published the synthesis and characterization of three series of Dke1 models featuring Fe(II)/acacX units (acacX = substituted β-diketonates) bound to facially coordinating N3 supporting ligands (LN3).12 These complexes incorporated acacX ligands with a range of steric and electronic properties. Following the labeling scheme employed in that paper (Scheme 1), the 1-acacX and 2-acacX complexes contain anionic Me2Tp and Ph2Tp donors, respectively. The [3-acacX]OTf series utilizes the neutral tris(2-phenylimidazoly-4-yl)phosphine (PhTIP) ligand, which was shown by spectroscopic and computational analysis to faithfully reproduce the 3His coordination environment of the Dke1 active site. The present manuscript describes the reactivity of these complexes with O2 and nitric oxide (NO) under a variety of conditions. To compare our results with those previously published by Siewert and Limberg, we have also generated three additional complexes that incorporate β-diester anions (i.e., acacOMe and acacPhmal in Scheme 1). Thus, we seek to expand upon previous discoveries that have demonstrated that synthetic Fe/acacX complexes are capable of performing Dke1-type chemistry. In those earlier works, no attempt was made to observe reactive intermediates, and each involved only one Fe complex. In this study, using low-temperature techniques, we have identified and characterized intermediates arising from treatment of our Dke1 models with O2 and NO. We have also systematically evaluated the role that solvent and ligand properties (both steric and electronic) play in modifying the O2 reactivity of our complexes. Thus, we have developed a more complete and extensive picture of the nature of O2 activation at nonheme Fe centers with relevance to Dke1.

Scheme 1.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. Acetonitrile, dichloromethane, and tetrahydrofuran were purified and dried using a Vacuum Atmospheres solvent purification system. The synthesis and handling of air-sensitive materials were performed under inert atmosphere using a Vacuum Atmospheres Omni-Lab glovebox equipped with a freezer set to −30 °C. Nitric oxide was purified by passage through an ascarite II column, followed by a cold trap at −78 °C to remove higher nitrogen oxide impurities. The LN3 supporting ligands K(Me2Tp),13K(Ph2Tp),14 and TIP15 were prepared according to literature procedures. With the exceptions of 1-acacOMe, 2-acacOMe, and 2-acacphmal, the synthesis and characterization of Fe(II) β-diketonato complexes in the 1-acacX, 2-acacX, and [3-acacX]OTf series were reported in our earlier manuscript.12

Physical Methods

Elemental analyses were performed at Midwest Microlab, LLC in Indianapolis, IN. UV–vis absorption spectra were obtained with an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrometer equipped with a cryostat from Unisoku Scientific Instruments (Osaka, Japan) for lowtemperature experiments. Infrared (IR) spectra were measured in solution using a Nicolet Magna-IR 560 spectrometer. 1H and 19F NMR spectra were collected at room temperature with a Varian 400 MHz spectrometer; 19F NMR spectra were referenced using the benzotrifluoride peak at −63.7 ppm. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiments were performed using a Bruker ELEXSYS E600 equipped with an ER4415DM cavity resonating at 9.63 GHz, an Oxford Instruments ITC503 temperature controller, and ESR-900 He flow cryostat. Mass spectra were recorded using an Agilent 6850 gas chromatography–mass spectrometer (GC-MS) with a HP-5 (5% phenylmethylpolysiloxane) column.

Synthesis of (Me2Tp)Fe(acacOMe)

Following the procedure published by Siewert et al.,11 dimethyl malonate (1.0 mmol) was deprotonated with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA; 1.1 mmol) in CH3CN, followed by addition of FeCl2 (1.0 mmol) and K(Me2Tp) (1.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight, filtered, and the volume reduced under vacuum. X-ray quality crystals were obtained by storing this solution at −30 °C for several days. Anal. Calcd for C20H29BFeN6O4: C, 49.62; H, 6.04; N, 17.36. Found: C, 49.72; H, 5.89; N, 17.82. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in toluene]: 315 (sh). IR (KBr, cm−1): 2952, 2930, 2526 [ν(BH)], 1638 [ν(CO)], 1542, 1498, 1451.

Synthesis of (Ph2Tp)Fe(acacOMe)

Li(acacOMe) was generated by treating dimethyl malonate (0.92 mmol) with LDA (1.0 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF), followed by removal of the solvent to yield the salt as a white powder. FeCl2 (0.92 mmol) and K(Ph2Tp) (0.92 mmol) were then combined with Li(acacOMe) in 15 mL of 1:3 CH2Cl2/CH3CN. The solution was stirred for 24 h, and the solvents were removed under vacuum. The white product was taken up in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 and filtered to remove insoluble salts. The resulting solution was layered with CH3CN to yield colorless crystals suitable for XRD studies. Anal. Calcd for C50H41BFeN6O4: C, 70.11; H, 4.82; N, 9.81. Found: C, 70.02; H, 4.82; N, 9.85. UV–vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in toluene]: 330 (400). IR (KBr, cm−1): 3061, 2950, 2616 [ν(BH)], 1632 [ν(CO)], 1503, 1460, 1304.

Synthesis of (Ph2Tp)Fe(acacPhmal)

Diethyl phenylmalonate (Phmal) (0.712 mmol) was stirred with LDA (0.790 mmol) for 30 min in 5 mL of THF. Removal of the solvent yielded a white salt that was dissolved in a 3:2 mixture of MeCN/CH2Cl2. Addition of FeCl2 (0.713 mmol) and K(Ph2Tp) (0.712 mmol) resulted in a cloudy gray solution that was stirred overnight. The solvents were removed under vacuum to yield a pale green solid that was taken up in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 and layered with CH3CN. After one day, light green crystals suitable for XRD were obtained. Anal. Calcd for C58H49BFeN6O4: C, 72.51; H, 5.14; N, 8.75. Found: C, 72.39; H, 5.11; N, 8.74. UV–vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in toluene]: 350 (1806). IR (neat, cm−1): 3024, 2974, 2614 [ν(BH)], 1615 [ν(CO)], 1594, 1544, 1478, 1463, 1448, 1433, 1405, 1375, 1337, 1303.

Crystallographic Studies

Six novel complexes were characterized using X-ray crystallography: 1-acacOMe, 2-acacOMe, 2-acacPhmal, 1-acacPhF3(NO), Fe(Ph2Tp)2, and [Fe3(O)(OH)(OBz)4(Me2Tp)2] (5-acacPhF3). Details concerning the data collection and analysis are summarized in Table 1 and Supporting Information, Table S1. The XRD data were collected at 100 K with an Oxford Diffraction SuperNova kappa-diffractometer equipped with dual microfocus Cu/ Mo X-ray sources, X-ray mirror optics, Atlas CCD detector, and a lowtemperature Cryojet device. The data were processed with CrysAlisPro program package (Oxford Diffraction Ltd., 2010) typically using a numerical Gaussian absorption correction (based on the real shape of the crystal) followed by an empirical multiscan correction using the SCALE3 ABSPACK routine. The structures were solved using the SHELXS program and refined with the SHELXL program16 within the Olex2 crystallographic package.17 All computations were performed on an Intel PC computer with Windows 7 OS. Some structures contain disorder that was detected in difference Fourier syntheses of electron density and accounted for using capabilities of the SHELX package. In most cases, hydrogen atoms were localized in difference syntheses of electron density but were refined using appropriate geometric restrictions on the corresponding bond lengths and bond angles within a riding/rotating model (torsion angles of methyl hydrogens were optimized to better fit the residual electron density).

Table 1.

Summary of X-ray Crystallographic Data Collection and Structure Refinement

| 1-acacOMe·MeCN | 2-acacOMe·1.5CH2Cl2 | 2-acacPhmal·MeCN | 1-acacPhF3(NO)·MeCN·0.5CH2Cl2b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| empirical formula | C24H35BFeN8O4 | C 51.5H44BCl3FeN6O4 | C60H52BFeN7O4 | C27.5H32BClF3FeN8O3 |

| formula weight | 566.26 | 983.94 | 1001.75 | 681.71 |

| crystal system | orthorhombic | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| space group | P212121 | P1̄ | P21/c | P21/n |

| a, Å | 12.62432(13) | 12.2090(3) | 38.1369(8) | 7.9307(2) |

| b, Å | 16.70885(18) | 13.0283(4) | 13.5597(3) | 19.6395(3) |

| c, Å | 13.70225(15) | 17.0877(5) | 20.5303(4) | 20.7317(5) |

| α, deg | 90 | 95.921(3) | 90 | 90 |

| β, deg | 90 | 103.201(3) | 104.121(2) | 91.126(2) |

| γ, deg | 90 | 117.095(3) | 90 | 90 |

| V, Å3 | 2890.32(5) | 2287.5(1) | 10295.9(4) | 3228.4(1) |

| Z | 4 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Dcalc, g/cm3 | 1.301 | 1.429 | 1.293 | 1.366 |

| λ, Å | 0.7107 | 0.7107 | 1.5418 | 1.5418 |

| µ, mm−1 | 0.565 | 0.559 | 2.789 | 4.782 |

| θ-range, deg | 3 to 29 | 3 to 62 | 7 to 148 | 9 to 148 |

| Reflections collected | 89285 | 49672 | 72082 | 28399 |

| independent reflections | 7745 [Rint = 0.0286] | 13415 [Rint = 0.0278] | 20374 [Rint = 0.0351] | 6454 [Rint = 0.0393] |

| data/restraints/parameters | 7745/0/354 | 13415/24/609 | 20374/0/1321 | 6454/0/445 |

| GOF (on F2) | 1.057 | 1.031 | 1.040 | 1.122 |

| R1/wR2 (I > 2σ(I))a | 0.0226/0.0608 | 0.0364/0.0861 | 0.0525/0.1393 | 0.0478/0.1268 |

| R1/wR2 (all data)a | 0.0251/0.0615 | 0.0463/0.0925 | 0.0570/0.1430 | 0.0546/0.1303 |

R1 = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑|Fo|; wR2 = [∑w(Fo2 – Fc2)2/∑w(Fo2)2]1/2.

The CH2Cl2 solvate in 1-acacPhF3(NO)·MeCN·0.5CH2Cl2 is only partially occupied.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

DFT calculations were performed using the ORCA 2.8 software package developed by Dr. F. Neese.18 Geometry optimizations employed the Becke–Perdew (BP86 functiona19 and Ahlrichs valence triple-ζ basis set (TZV) for all atoms, in conjunction with the TZV/J auxiliary basis set.20 Extra polarization functions were used on non-hydrogen atoms. The effect of toluene solvation on computational energies was accounted for using the conductor-like screening model (COSMO). The same basis set was used for time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations,21 which computed absorption energies and intensities within the Tamm–Dancoff approximation.22 In each case, at least 80 excited states were calculated. Finally, the gOpenMol program developed by Laaksonen23 was used to generate isosurface plots of molecular orbitals.

3. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

3.A. Synthesis, Solid State Structures, and Spectroscopic Features of Fe(II) Complexes

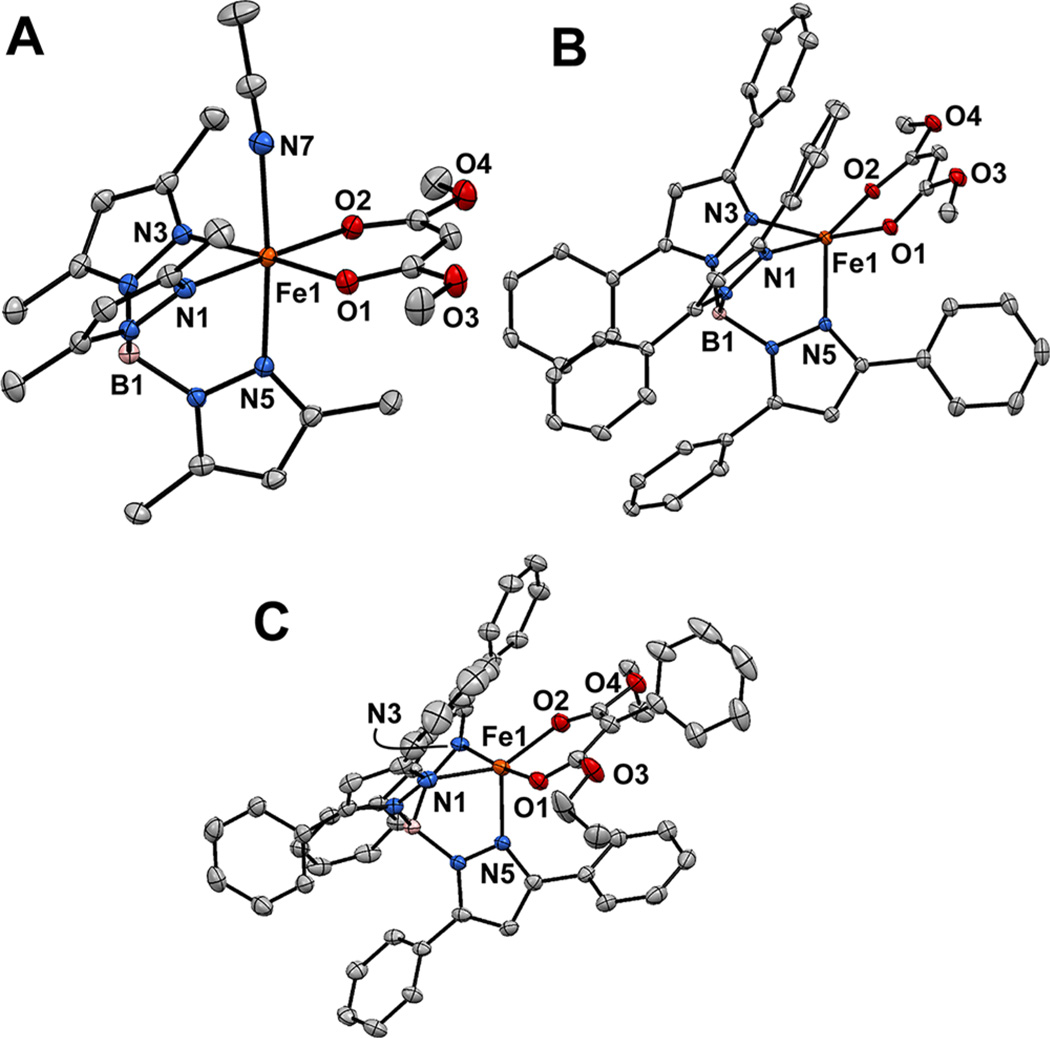

Following earlier procedures,11,12 the iron(II) complexes 1-acacOMe, 2-acacOMe, and 2-acacPhmal were prepared by reacting equimolar amounts of K(R2Tp), FeCl2, LDA, and dimethyl malonate or diethyl phenylmalonate. The resulting X-ray crystal structures are shown in Figure 1 and selected metric parameters are provided in Table 2. Like other members of the 1-acacX series,12 1-acacOMe features an octahedral Fe(II) center with a facially coordinating Me2Tp ligand, bidentate acacOMe group, and MeCN. The average Fe–NTp and Fe–Oacac distances of 2.170 and 2.087 Å, respectively, resemble the values found for 1-acac and are characteristic of high-spin six-coordinate (6C) Fe(II) complexes. The Ph2Tp complexes 2-acacOMe and 2-acacPhmal exhibit distorted 5C square-pyramidal geometries (τ = 0.03 and 0.39, respectively24) with a pyrazole ligand in the axial position. The lack of bound MeCN shortens the Fe–NTp and Fe–Oacac distances in 2-acacOMe and 2-acacPhmal relative to 1-acacOMe (Table 2). Because of steric interactions with the 3-Ph group of the axial pyrazole, the acacOMe ligand is tilted out of the N1–Fe1–N3 plane by ~30°.

Figure 1.

Thermal ellipsoid plots (50% probability) derived from 1-acacOMe MeCN (A), 2-acacOMe·1.5 CH2Cl2 (B), and 2-acacPhmal MeCN (C). Hydrogen atoms and noncoordinating solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Selected metric parameters are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Bond Angles (deg) for 1-acacOMe·MeCN, 2-acacOMe·1.5CH2Cl2, and 2-acacPhmal·MeCN

| 1-acacOMe· MeCN |

2-acacOMe· 1.5CH2Cl2 |

2-acacPhmal· MeCNa |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe–O1 | 2.092(1) | 2.042(1) | 1.982(2) |

| Fe–O2 | 2.083(1) | 2.046(1) | 2.065(2) |

| Fe–N1 | 2.155(1) | 2.151(1) | 2.214(2) |

| Fe–N3 | 2.162(1) | 2.154(1) | 2.105(2) |

| Fe–N5 | 2.194(1) | 2.129(1) | 2.076(2) |

| Fe–N7 | 2.252(1) | ||

| Fe–Oacac (ave) | 2.087 | 2.044 | 2.024 |

| Fe–NTp (ave) | 2.170 | 2.144 | 2.132 |

| O1–Fe–O2 | 86.70(3) | 87.50(4) | 86.34(6) |

| O1–Fe–N1 | 90.18(3) | 92.16(4) | 97.02(7) |

| O1–Fe–N3 | 177.00(3) | 159.16(4) | 147.45(7) |

| O1–Fe–N5 | 94.25(3) | 108.31(4) | 120.57(7) |

| O2–Fe–N1 | 176.86(4) | 157.09(4) | 170.87(7) |

| O2–Fe–N3 | 96.17(3) | 88.54(4) | 90.05(7) |

| O2–Fe–N5 | 92.16(4) | 109.58(4) | 95.66(7) |

| N1–Fe–N3 | 86.95(4) | 83.68(4) | 82.54(7) |

| N1–Fe–N5 | 88.45(4) | 92.28(4) | 89.95(7) |

| N3–Fe–N5 | 84.78(4) | 92.29(4) | 91.98(7) |

| τ-valueb | 0.03 | 0.39 |

The unit cell of 2-acacPhmal·MeCN contains two symmetrically independent complexes with nearly identical geometries. Only parameters of the first complex are shown.

For a definition of the τ-value, see reference 24. A five-coordinate complex with ideal squarepyramidal geometry would have a τ-value of 0.0, while those with ideal trigonal bipyramidal geometry would have a value of 1.0.

Most Fe(R2Tp)(acacX) complexes are brightly colored because of the presence of Fe2+→acacX (C=O*) metal-toligand charge-transfer (MLCT) transitions in the visible region.12 The acacOMe and acacPhmal complexes are colorless, however, as the corresponding MLCT bands appear in the UV-region, reflecting the electron-rich nature of the dialkyl malonate anions. The 1H NMR spectra of these complexes exhibit broad, paramagnetically shifted peaks consistent with the presence of a high-spin Fe(II) center. For both 1-acacOMe and 2-acacOMe, resonances arising from the methyl groups of the acacOMe moieties appear near 8 ppm in CD2Cl2. The remaining R2Tp-derived peaks largely follow the patterns previously described for complexes in the 1-acacX and 2-acacX series,12,25 and detailed assignments and T1-relaxation values are provided in Supporting Information, Table S2.

Attempts to generate the analogous Fe(II)/β-diester complexes with the PhTIP ligand (i.e., [3-acacOMe]+ or [3-acacPhmal]+) were not successful. This failure is perhaps due to the elevated basicities of the dialkyl malonate anions, which are incompatible with the unprotected H–N groups of the PhTIP ligand.26

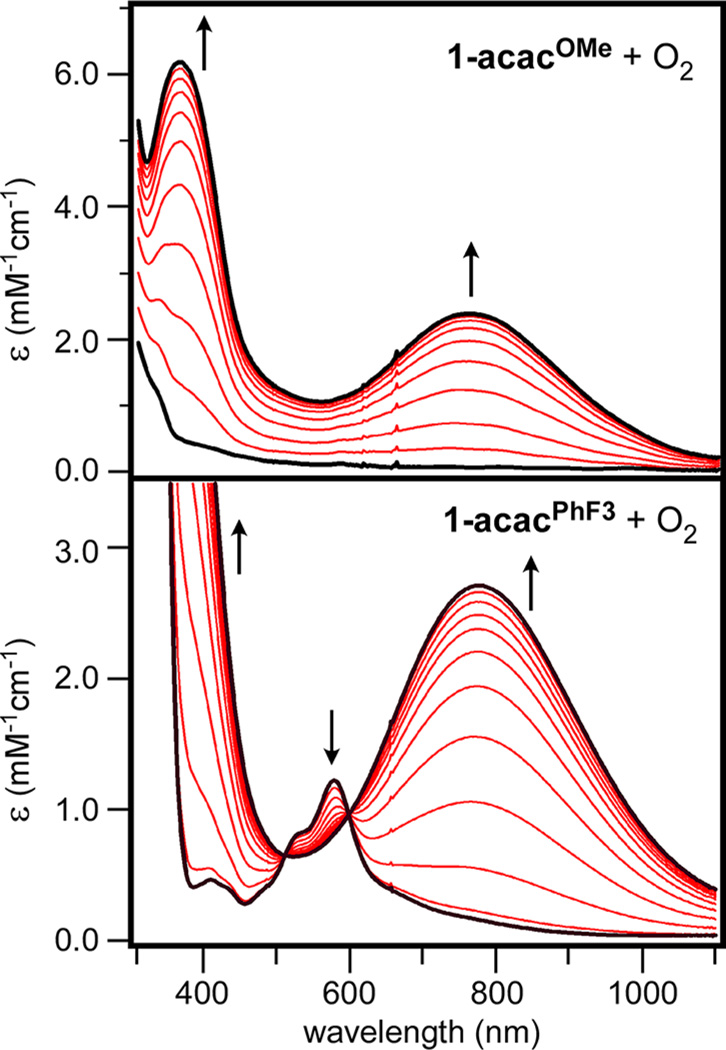

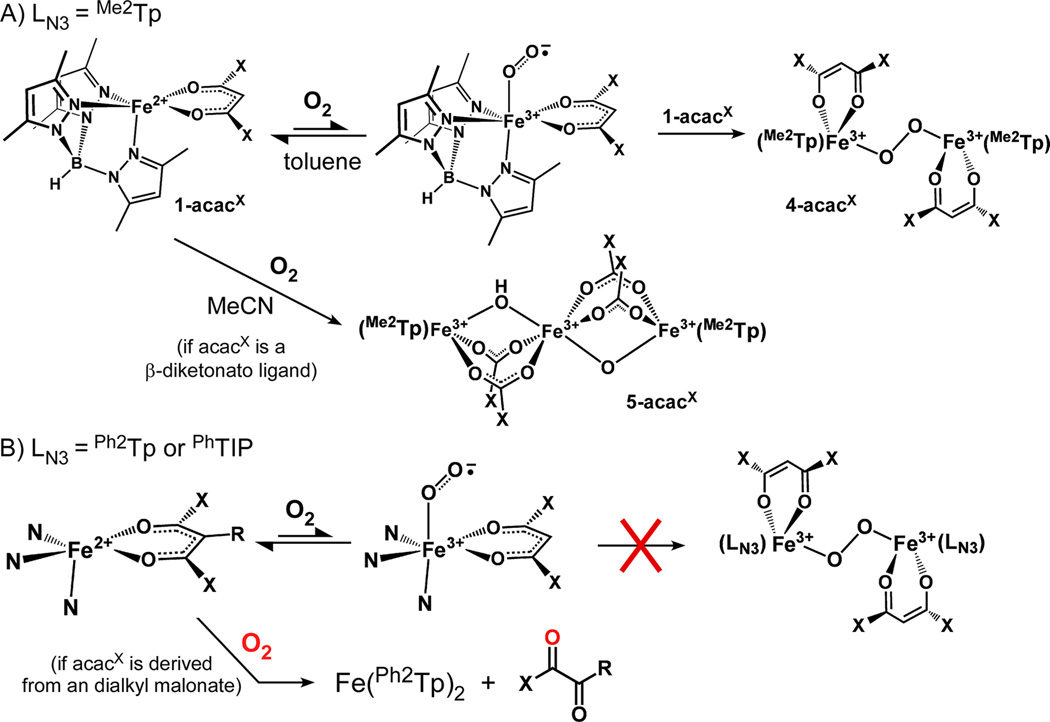

3.B. Oxygenation of Fe(II) Complexes

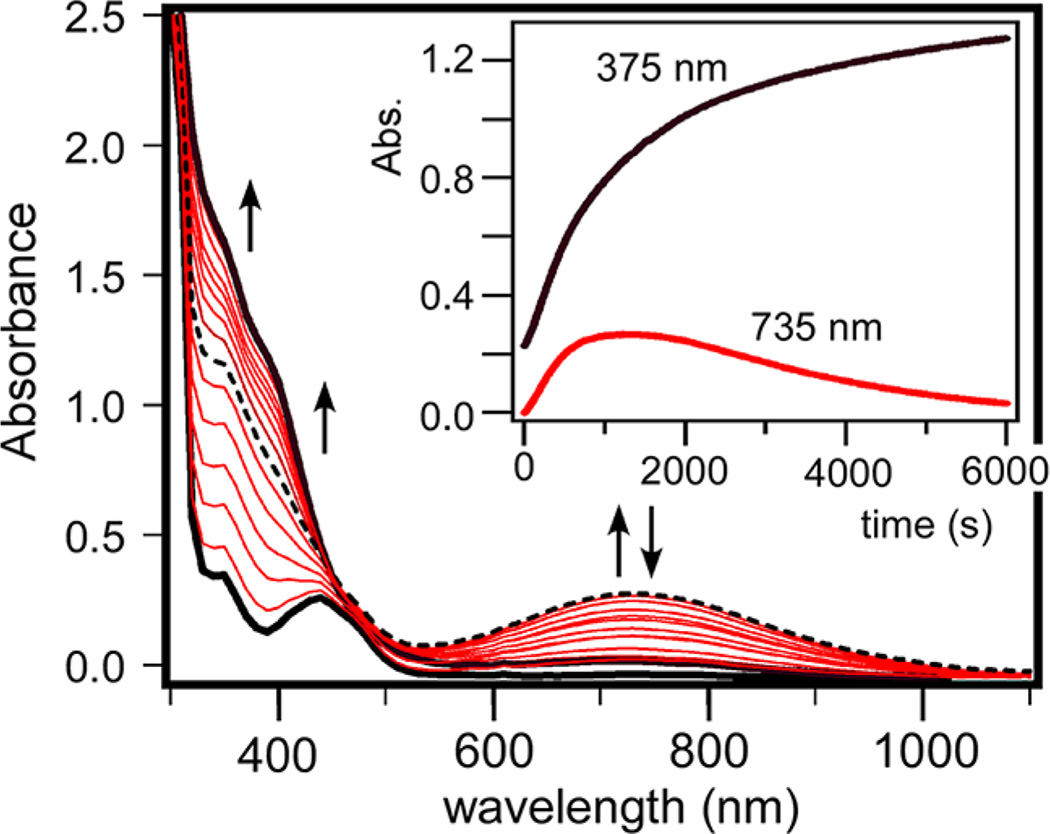

As shown in Figure 2A, exposure of 1-acacOMe to O2 at −70 °C in toluene gives rise to a dark green intermediate (4-acacOMe) with an intense absorption band at 756 nm (ε = 2400 M−1 cm−1 per Fe). The oxygenation reaction is irreversible and the intermediate quickly decays at temperatures above −60 °C. Similar spectral changes are observed upon oxygenation of 1-acac and 1-acacF3 (Supporting Information, Figure S1) in toluene. Time-dependent absorption spectra of the reaction of 1-acacPhF3 with O2 (Figure 2B) display isosbestic points at 510 and 600 nm, indicative of clean conversion of 1-acacPhF3→4-acacPhF3 without the build-up of intermediates. While each green intermediate displays a prominent absorption band in the near-IR region, the energy and intensity of this band varies considerably within the series, suggesting that the acacX ligand remains iron-bound and capable of modulating the electronic structures of 4-acacX (vide infra). Interestingly, 1-acacF6 does not give rise to a green intermediate upon treatment with O2, suggesting that the electron-poor acacF6 ligand deactivates the complex.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent absorption spectra of the reaction of 1-acacOMe (top) and 1-acacPhF3 (bottom) with O2 at −70 °C in toluene. The molar absorptivities of the resulting 4-acacX intermediates are based on the initial concentrations of the 1-acacX precursors.

Formation of the green intermediates is hindered by the presence of coordinating solvents, such as MeCN and MeOH. As shown in Figure 3, oxygenation of 1-acac in MeCN at −40 °C initially generates a broad absorption feature at 735 nm that likely corresponds to 4-acac. This feature never reaches full intensity, however, because of a competing decay process that eventually yields a species (5-acac) with two intense, overlapping bands in the near-UV region. For other 1-acacX complexes (X = OMe, F3, and PhF3), the transient absorption band of the green intermediate is never observed during the reaction with O2 in MeCN or MeOH; instead, these complexes directly convert to intermediates with UV–vis features similar to 5-acac (Supporting Information, Figure S2). The 1-acacX→ 5-acacX conversion occurs rapidly at −40 °C in the case of 1-acacOMe, whereas the process requires several days at room temperature for compounds with fluorinated acacX ligands. Significantly, the addition of MeOH to toluene solutions of already-formed green intermediates results in immediate decay to the corresponding 5-acacX species, even at −70 °C. This behavior indicates that 4-acacX species are not stable in the presence of coordinating solvents.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent absorption spectra of the reaction of 1-acac (0.4 mM) with O2 at −40 °C in MeCN. Inset: Absorption intensity at 375 and 735 nm as a function of time.

The 5-acacX complexes are not simply the one-electron oxidized forms of 1-acacX (i.e., [Fe3+(Me2Tp)(acacX)]+), since treatment of 1-acacX complexes with ferrocenium salts yields chromophores with very different absorption features (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Instead, the spectral features resemble those reported by Kitajima et al. for the linear trinuclear ferric complex [Fe3+3(O)(OH)(OAc)4(iPr2Tp)2] (6), which is generated upon exposure of [Fe2+(iPr2Tp)(acac)] to O2 in MeCN (as noted in the Introduction).10 In support of this assignment, the EPR spectra of 5-acac and 5-acacPhF3 display an intense feature at g = 4.3 and a weaker peak at g = 8.83 (Supporting Information, Figure S3), identical to the spectrum reported for 6. In addition, crystals of 5-acacPhF3 were obtained by allowing an aerobic solution of 1-acacPhF3 in MeCN to stand for several weeks. XRD analysis revealed a triiron complex with Cs symmetry analogous to 6 (Supporting Information, Figure S4). The Fe centers in 5-acacPhF3 are bridged by four benzoate ligands derived from the acacPhF3 ligand, as well as two µ-O(H) ligands. It is reasonable to assume that 5-acac and 5-acacF3 adopt similar structures. In the case of 5-acacOMe, however, the resulting methyl carbonate anion would decompose to CO2 and methoxide, and therefore a trinuclear structure with bridging carboxylate ligands is unlikely. Attempts to crystallize 5-acacOMe have not succeeded to date. Regardless, our spectroscopic and crystallographic data prove that the reaction of [Fe(Me2Tp)(acacX)] complexes (where acacX is a β-diketonate) with O2 in coordinating solvents results in cleavage of the acacX ligand, in agreement with previous studies by Kitajima10 and Limberg11 with related complexes.

Treatment of Fe(II) complexes in the 2-acacX and [3-acacX]+ series with O2 failed to generate the corresponding green intermediates or triiron complexes under any conditions. These complexes react slowly, or not at all, with O2 in both coordinating and noncoordinating solvents. For instance, the UV–vis absorption and 19F NMR spectra of 2-acacF3, 2-acacPhF3, and [3-acacF3]+ in O2-saturated toluene solutions exhibit no significant changes over the course of several days at room temperature. Only the β-diester complexes 2-acacOMe and 2-acacPhmal exhibit perceptible reactivity toward O2. Exposure of these complexes to O2 eventually yields colorless crystals that were shown by XRD to consist of Fe(Ph2Tp)2 (Supporting Information, Figure S5), suggesting that the acac ligands are degraded in the process.27 Monitoring the O2 reaction with 1H NMR spectroscopy in toluene-d8 revealed that the paramagnetically shifted peaks of 2-acacOMe and 2-acacPhmal slowly disappear, concomitant with the growth of peaks arising from methyl 2-oxoacetate and ethyl benzoylformate, respectively. The formation of ethyl benzoylformate was also verified by GC-MS. When the reaction with 2-acacPhmal was performed with 18O-enriched dioxygen, GC-MS analysis indicated that one O-atom of ethyl benzoylformate is derived from O2, proving that the observed products are due to dioxygenolytic cleavage of the ligand (the alkyl carbonate products that are also generated quickly decompose to CO2 and the corresponding alkoxide). Thus, our Ph2Tp-based complexes are capable of performing Dke1-type chemistry on a reasonable time scale provided that the substrate ligand is sufficiently activated. The rates of the O2 reactions in toluene were measured using UV-vis absorption spectroscopy. 2-acacPhmal decays relatively quickly in the presence of O2 (kO2 = 3.4 × 10−4 s−1; Supporting Information, Figure S6), whereas 2-acacOMe requires more than a day for complete reaction (kO2 ~ 4 × 10−5 s−1).

The observed reactivity trends of the Dke1 models cannot be rationalized on the basis of redox potentials. For instance, the Fe3+/Fe2+ redox couple measured for the largely inert 2-acac (−58 mV) is slightly more negative then the values for 1-acacF3 (−34 mV vs Fc+/0) and 1-acacPhF3 (0 mV)12 which react rapidly with O2 to generate 4-acacX intermediates. In addition, cyclic voltammetric studies indicate that 2-acacPhmal is actually harder to oxidize than 2-acac (Supporting Information, Figure S7); yet it is the former complex that carries out dioxygenolytic cleavage. Within the 2-acacX series, it appears that O2 reactivity is primarily governed by the relative energies of acacX π-electrons, not the Fe redox potentials. This conclusion is consistent with a prior study of Straganz that found a direct correlation between kcat and the energy of the acacX highestoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO).8

One might also ascribe the sluggish O2 reactivity of the 2-acacX and [3-acacX]+ series to the increased steric bulk of the phenyl substituents, which appear to block access to the vacant coordination site in the X-ray crystal structures (Figure 1). However, this assumption is contradicted by our experiments with NO (vide infra). To understand the divergent O2 chemistry of these complexes, it is necessary to identify the structure of the 4-acacX species formed upon reaction of some 1-acacX complexes with O2.

3.C. Spectroscopic and Computational Characterization of 4-acacX Intermediates

Several pieces of evidence suggest that the green intermediates (4-acacX) contain a diiron(III)-peroxo unit. First, the observed spectral features and the manner of preparation are very similar to those of the cis µ-1,2-peroxo bridged complex [Fe2(O2)(µ-O2CR)2(iPr2Tp)2] (7; R = Ph or CH2Ph) first prepared by Kitajima and co-workers.28 This complex is generated via the reaction of [Fe2+(O2CR)-(iPr2Tp)] with O2 in toluene at −20 °C and features a band at 682 nm (ε = 1730 M−1 cm−1 per Fe) that arises from a peroxo→Fe(III) charge transfer transition.29 Even more relevant to the current study is Kitajima’s report that [Fe2+(acac)(iPr2Tp)] reacts with O2 in toluene to give a green intermediate that is unstable even at −78 °C.10 Although no spectroscopic characterization was performed, this species was presumed to be a µ-peroxo species. Second, we examined 4-acac with magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectroscopy, which is sensitive to the ground-state spin of chromophores. As shown in Supporting Information, Figure S8, MCD spectra of 4-acac fail to exhibit any temperature-dependent intensity in the 600–900 nm region. This result provides strong evidence in favor of an antiferromagnetically coupled diiron species (Stotal = 0), while simultaneously ruling out a mononuclear Fe3+ or high-spin Fe2+ assignment for 4-acac. Finally, EPR spectra of 4-acacX are featureless apart from a weak peak at g = 4.3 from the decomposition product (less than 10% of the Fe in the sample based on double integration of the signal30). Collectively, these results point to the formulation of 4-acacX as [Fe2(µ-O2)(acacX)2(MeTp)2] intermediates. Unfortunately, further confirmation with resonance Raman spectroscopy has not been successful because of rapid photodecomposition of the green intermediates even at low laser power.

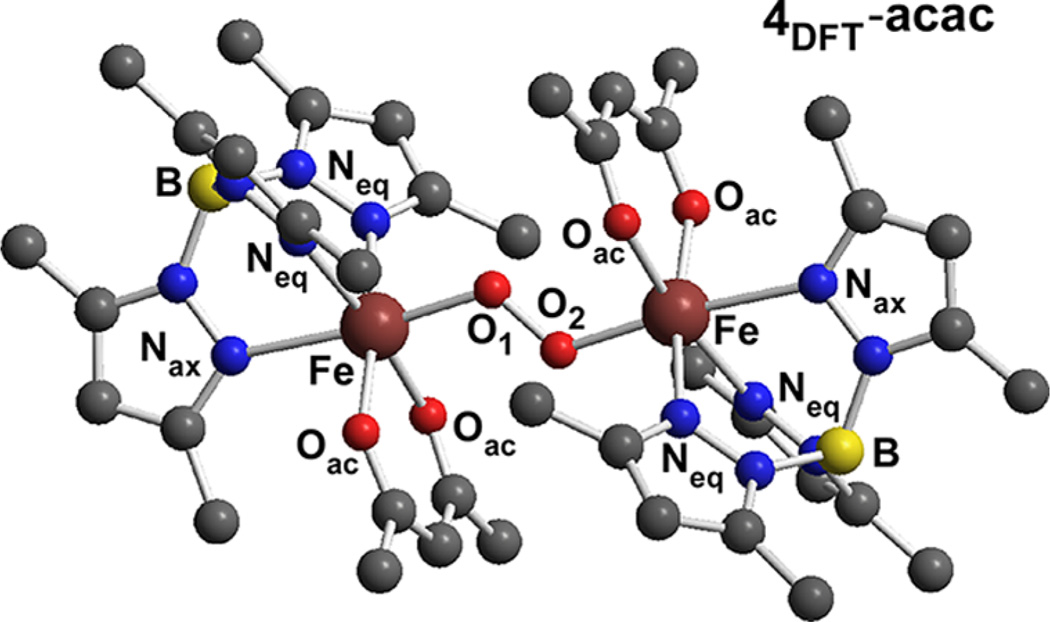

Possible structures for the 4-acac intermediate were evaluated using DFT calculations. In the X-ray structure of 7, the peroxo ligand adopts a cis µ-1,2-peroxo mode with two carboxylate ligands occupying µ-1,3 bridging positions between the two Fe3+ centers.28b An analogous structure is not possible for 4-acac, since the acac ligands are not capable of bridging in a µ-1,5 fashion.31 Given that each Fe center is likely coordinated to a single acac ligand, the most plausible structure of 4-acac is a trans µ-1,2-peroxo diiron(III) complex with idealized C2h symmetry, as shown in Figure 4. Geometry optimizations based on this orientation were carried out for the high-spin (HS), ferromagnetic state with Stot = 5. While it is known from experiment that 4-acac exhibits antiferromagnetic coupling, attempts to account for this fact with the broken- symmetry (BS) approach of Noodleman were not successful because of SCF convergence difficulties. Regardless, previous DFT studies of transition metal dimers have demonstrated that HS and BS calculations generally provide similar geometries, and thus the HS models are sufficient for our purposes.

Figure 4.

Model of 4-acac derived from DFT geometry optimizations. The computed structure exhibits almost perfect C2h symmetry. Computed bond distances (Å) and angles (deg): Fe–O1(2) 1.994, Fe–Neq (ave) 2.173, Fe–Nax 2.364, Fe–Oac (ave) 2.037, O1–O2 1.389, Fe…Fe 4.882, Fe–O1–O1 122.8.

Significant metric parameters for the DFT-derived model of 4-acac (4DFT-acac) are provided in the caption of Figure 4. The computed O–O bond distance of 1.39 Å is characteristic of bridging peroxo ligands, and the Fe2O2 unit features Fe–O–O angles of 123° and a Fe–O–O–Fe dihedral angle near 180°. The trans µ-1,2 coordination of the peroxo moiety, combined with the fewer number of bridging ligands, results in a much larger Fe-Fe separation in 4DFT-acac (4.88 Å) than the crystal structure of 7 (4.00 Å). As a result, the Fe–Operoxo bonds in 4DFT-acac are elongated by 0.09 Å relative to their counterparts in 7.33

To validate the structure of 4DFT-acac on the basis of experimental data, electronic transition energies were calculated using time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT). The computed spectrum (Supporting Information, Figure S9) features a dominant band at 879 nm (11380 cm−1) with an e-value of 6300 M−1 cm−1 per Fe, in reasonable agreement with the experimentally observed feature at 740 nm (13510 cm−1) with an e-value of 3500 M−1 cm−1. As expected, TD-DFT attributes this band to a peroxide(ππ*)→ Fe(3dxz) charge transfer transition. The intensity of this feature is enhanced by the planarity of the Fe2O2 unit in 4DFT-acac, which optimizes π-overlap between the ππ* and 3dxzorbitals. For the sake of comparison, the TD-DFT methodology was also applied to a geometry-optimized model of complex 7. The resulting calculation predicts a peroxide→ Fe CT transition at 788 nm (12690 cm−1) with an intensity of 2200 M−1 cm−1 per Fe (experimentally, this band appears at 682 nm with ε = 1730 M−1 cm−1 per Fe29). It therefore appears that TD-DFT underestimates the transition energies and overestimates the intensities of CT features in diferric-peroxo complexes. Regardless, the computational results indicate that the principal peroxide→Fe CT transition of the putative trans µ-1,2 peroxo complex 4-acac should be lower in energy and greater in intensity than the corresponding transition of the cis µ-1,2 peroxo complex 7, which is fully consistent with our experimental observations.

Finally, computational methods were used to evaluate the stabilities of the diiron(III)-peroxo complexes relative to their 5C Fe2+ precursors and O2. DFT-derived energies indicate that formation of 7, via the reaction: 2Fe2+ + O2 → Fe2(µ-O2), is more thermodynamically favorable than the formation of 4-acac by nearly 14 kcal/mol.34 This computational result is supported by numerous experimental observations that point to the greater stability of 7 relative to 4-acac: (i) 7 is metastable at −20 °C,28a whereas 4-acac decays rapidly at temperatures above −60 °C, (ii) X-ray quality crystals of 7 were obtained at low temperature, whereas crystallization of 4-acac has proven futile to date, and (iii) 7 is more resistant to photodecomposition than 4-acac. The enhanced stability of 7 relative to 4-acac is likely due to the presence of the two bridging carboxylate ligands in the former.

On the basis of the spectroscopic and computational results presented here, we are confident that the 4-acacX chromophores correspond to diferric-peroxo complexes with trans µ-1,2-peroxo orientations, as shown in Figure 4 for 4-acac.

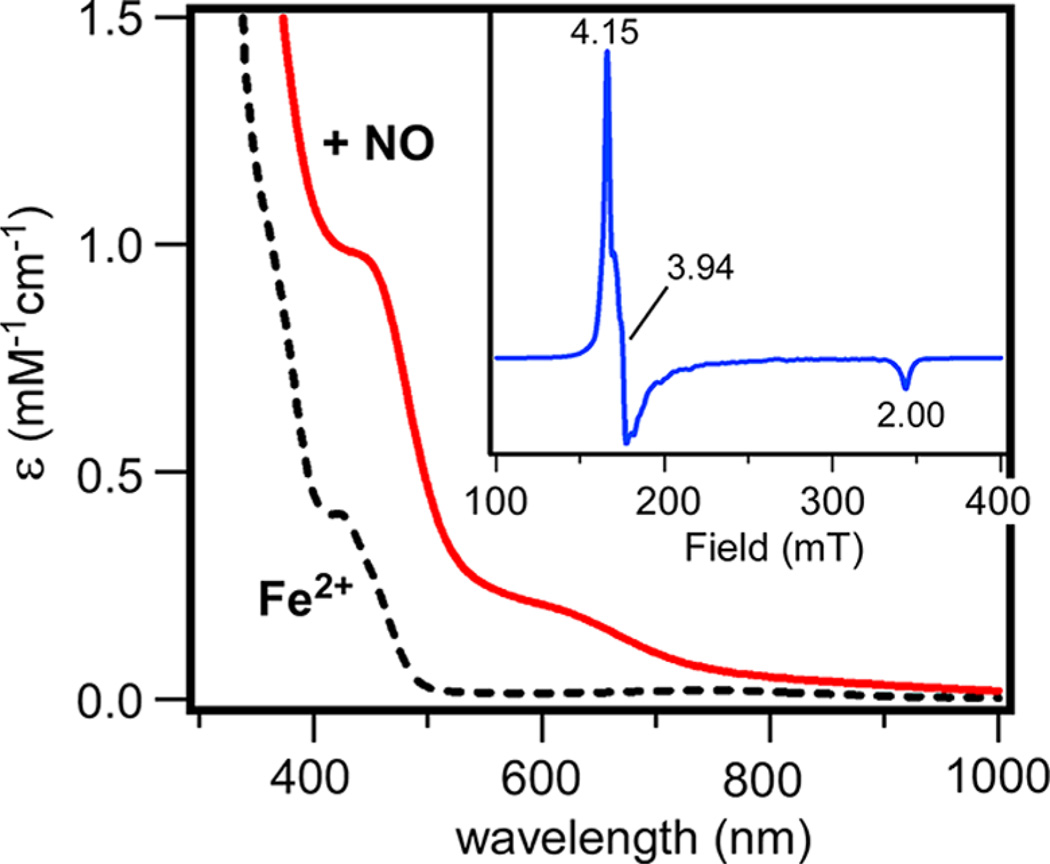

3.D. Reaction with Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide has been frequently used to probe the ferrous states of nonheme Fe enzymes and related complexes. Each of our Dke1 models, regardless of its supporting ligand, rapidly reacts with NO to yield the corresponding {FeNO}7 species (according to the Enemark-Feltham notation35). As shown in Figure 5 for the representative reaction of 2-acac with NO, formation of the greenish-brown Fe-NO adduct, 2-acac(NO), is evident in the appearance of two absorption bands near 440 and 620 nm that are characteristic of 6C {FeNO}7 species36 (absorption spectra of all Fe-NO adducts generated as part of this study are shown in Supporting Information, Figures S10–S12). While ironnitrosyl complexes with R2Tp supporting ligands have long lifetimes at room temperature (RT), the 3-acac(NO) species is only moderately stable at −40 °C in MeCN. The nitrosyl complexes are uniformly high-spin (S = 3/2), displaying nearly axial EPR spectra with gx ≈ gy ≈ 4.0 and gz = 2.0 (Figure 5, inset; see Supporting Information, Figures S12 and S13 for additional EPR data). In spectra measured in frozen CH2Cl2, poorly resolved superhyperfine splitting from the nitrogen ligands is evident in the gx and gy features. FTIR spectra of the NO adducts each revealed a prominent peak between 1720 and 1761 cm−1 arising from the stretching mode of the bound nitrosyl ligand. These νNO frequencies are typical for high-spin, nonheme {FeNO}7 complexes with 6C geometries.37

Figure 5.

Absorption spectra of 2-acac in CH2Cl2 at room temperature before and after addition of NO. Inset: X-band EPR spectrum of the Fe-NO adduct of 2-acac in frozen CH2Cl2 ([Fe] = 1.5 mM). Instrumental parameters: frequency = 9.629 GHz; power = 2.0 mW; modulation = 12 G; temperature = 10 K.

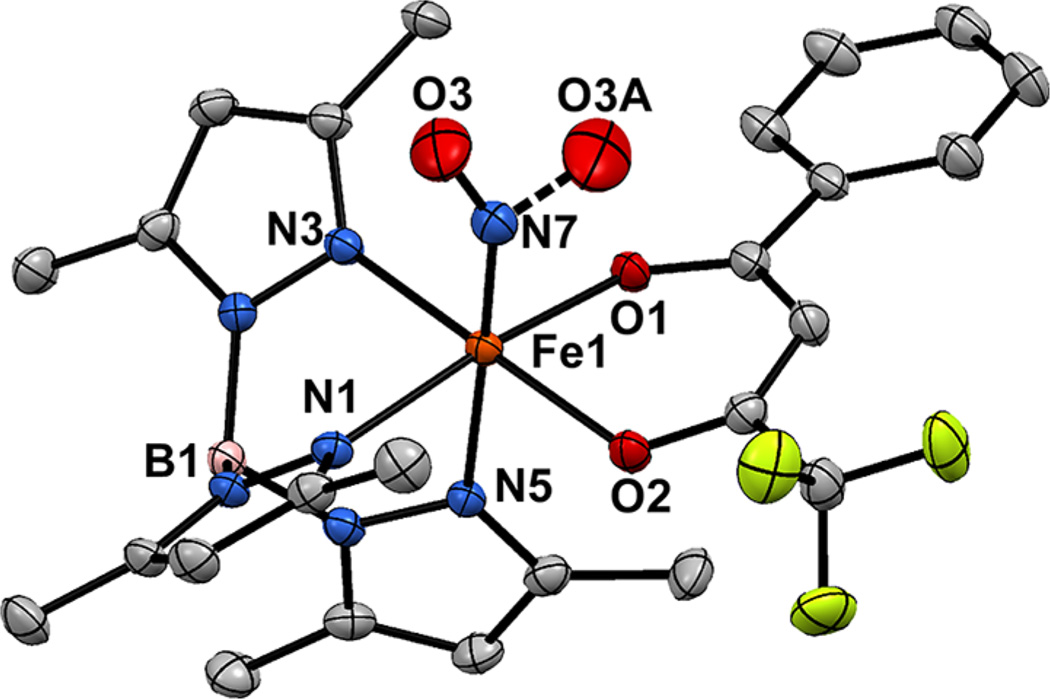

X-ray quality crystals of 1-acacPhF3(NO) were obtained by slowly cooling a NO saturated solution of 1-acacPhF3 in 1:1 MeCN:CH2Cl2. The crystal structure confirms the coordination of a NO ligand to the Fe center, providing a distorted octahedral geometry (Figure 6). Selected bond distances and angles for 1-acacPhF3(NO) are provided in Table 3. The FeNO unit is disordered over two positions in a 3:1 ratio with Fe1– N7–O3(A) angles of 147.7(3)° (major) and 139.4(6)° (minor).38 As shown in Figure 6, the NO ligand in the major structural component is facing away from the acacPhF3 ligand, such that the projection of the NO bond vector bisects the N1– Fe–N3 angle (the N3–Fe1–N7–O3 dihedral angle is 41.5(5)°). In the minor structural component, the NO bond vector points in the opposite direction, bisecting the O1–Fe1– O2 angle of the acacPhF3 ligand; this orientation is similar to one likely adopted by O2 in the Dke1 active site. Interestingly, the Fe1–N7 distance of 1.813(3) Å measured for 1-acacPhF3(NO) is significantly longer than the average Fe–NNO distance of ~1.73 Å found in comparable nonheme {FeNO}7 complexes, while the observed N–O distance of 1.148(4) Å is slightly shorter than the average value of ~1.16 Å.37

Figure 6.

Thermal ellipsoid plots (50% probability) derived from the X-ray structure of 1-acacPhMe(NO)·MeCN·0.5CH2Cl2. Hydrogen atoms and noncoordinating solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. The oxygen atom of the NO ligand (O3) is distorted over two positions in a 3:1 ratio. Selected metric parameters are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Bond Angles (deg) for 1-acacPhF3·MeCN and 1-acacPhF3(NO)·MeCN·0.5CH2Cl2 Obtained via XRD Experimentsa

| XRD |

DFT |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-acacPhF3 MeCN |

1-acacPhF3(NO). MeCN·0.5CH2Cl2 |

1-acacPhF3(NO) | |

| Fe–Ol | 2.064(1) | 2.064(2) | 2.104 |

| Fe–O2 | 2.073(1) | 2.069(2) | 2.097 |

| Fe–Nl | 2.144(1) | 2.109(2) | 2.136 |

| Fe–N3 | 2.164(1) | 2.112(2) | 2.140 |

| Fe–NS | 2.170(1) | 2.203(2) | 2.219 |

| Fe–N7 | 2.255(1) | 1.813(3) | 1.761 |

| Fe–Oacac (ave) | 2.069 | 2.067 | 2.101 |

| Fe–NTp (ave) | 2.158 | 2.141 | 2.165 |

| N7–O3 | 1.148(4) | 1.176 | |

| Fe–N7–O3 | 147.7(3) | 143.4 | |

| O1–Fe–N3 | 175.48(5) | 174.2(1) | 172.9 |

| O2–Fe–Nl | 177.83(5) | 170.0(1) | 173.4 |

Metric parameters for the DFT-computed structure of 1-acacPhF3(NO) are also included.

The geometric changes arising from NO binding are evident in a comparison of the structure of 1-acacPhF3(NO) with its precursor 1-acacPhF3 (Table 3). The trans influence of the nitrosyl ligand results in a lengthening of the Fe–N5 bond from 2.170(1) to 2.203(2) Å, and the Fe atom moves out of the N2O2 plane by 0.13 Å. In contrast, the equatorial Fe–NTp bonds shorten by an average of 0.044 Å upon NO coordination, while the Fe–Oacac distances remain the same within experimental error. The internal metric parameters of the acacPhF3 ligand are unchanged to within experimental error.

Using the X-ray structure as a starting point, the electronic structure of 1-acacPhF3(NO) was examined with spin-unrestricted DFT calculations employing the nonhybrid BP86 functional.39 As shown in Table 3, the energy-minimized structure of 1-acacPhF3(NO) is reasonably consistent with the crystallographic data, exhibiting a rms deviation of 0.034 Å in the first-sphere Fe–N/O bond distances. However, DFT fails to reproduce the elongated Fe–N(O) bond observed for 1-acacPhF3(NO), instead providing a more conventional value of 1.761 Å. DFT calculations employing hybrid functionals, such as B3LYP, resulted in Fe-N(O) distances that were too long (>1.84 Å), while also overestimating the Fe–Oacac/NTp distances to a greater degree than the BP86 structure. Thus, the BP model is likely the most accurate representation of the gas-phase structure of 1-acacPhF3(NO).

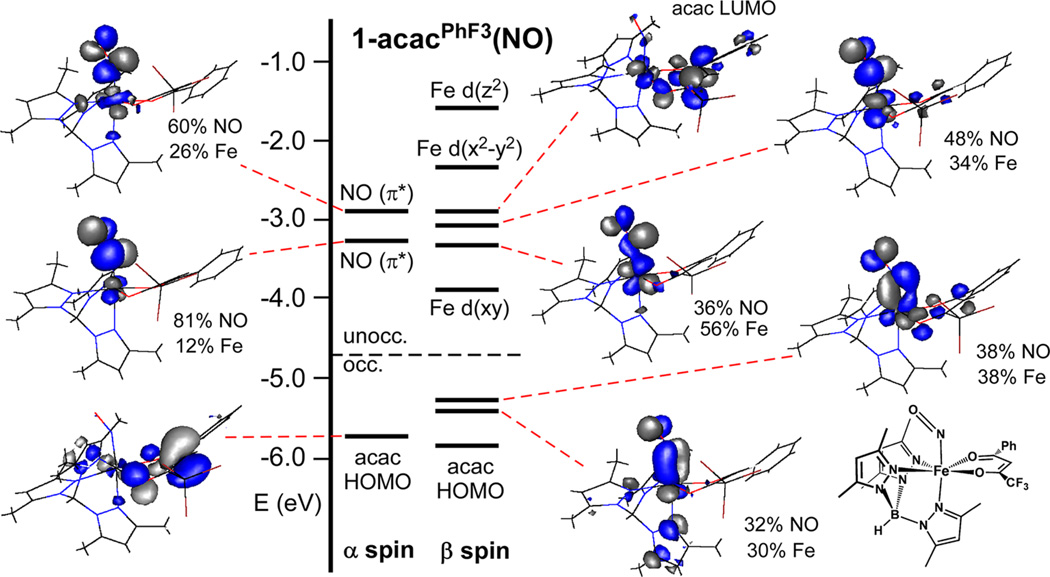

The computed molecular orbital (MO) energy level diagram for 1-acacPhF3(NO) in the S = 3/2 ground state is shown in Figure 7. The frontier orbitals are primarily derived from the Fe 3d, NO(π*), and acacPhF3 orbitals. The highest-occupied acac- based MO (acac HOMO) features a large lobe of electron density on the central carbon atom, corresponding to the acac “lone-pair”, while the lowest-unoccupied acac-based MO (acac LUMO) has largely C=O* character. The two lowest-unoccupied spin-up (α) MOs are mainly composed of NO(π*) character, indicating that the spin of the nitrosyl ligand is aligned opposite to the Fe spin (i.e., antiferromagnetic coupling). As illustrated by the contour plots shown in Figure 7, the Fe 3d(xz) and 3d(yz) orbitals interact strongly with the two spin-down (β) NO(π*) orbitals. These MOs contain roughly equal amounts of Fe 3d and NO(π*) character, and the same is true of their (unoccupied) antibonding counterparts. The high covalency of the Fe–NO bond makes it challenging to conclusively assign oxidation states for 1-acacPhF3(NO), a difficulty encountered for nearly all iron nitrosyl complexes. Nonheme NO complexes with S = 3/2 have typically been described as high-spin Fe3+ centers (S = 5/2) coupled to NO‾ (S = 1)36a. Consistent with this formulation, the energies of the Fe 3d(xy)- and 3d(x2 – y2)-based MOs, which are nonbonding with respect to the axial ligands, decrease by approximately 0.9 eV upon conversion of 1-acacPhF3→1-acacPhF3(NO), indicating a significant increase in the Fe effective nuclear charge. The large amount of Fe 3d character (~34%) in the spin-down HOMOs, however, suggests that the electron is only partially transferred from Fe to NO, resulting in an oxidation state between Fe3+ and Fe2+.

Figure 7.

Molecular orbital energy-level diagram obtained from DFT calculations of 1-acacPhF3(NO). MOs are labeled according to their principal contributor. DFT-generated isosurface plots and compositions of selected orbitals are also provided.

In many respects, 1-acacPhF3(NO) resembles an {FeNO}7 adduct recently synthesized and crystallographically characterized by Berto and Lehnert, namely, [Fe(NO)(Cl)(BMPA-Pr] (8; where BMPA-Pr is N-propanoate-N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine). Like 1-acacPhF3(NO), complex 8 exhibits an axial S = 3/2 EPR sigand, along with a relatively long Fe–N(O) bond distance of 1.783 Å. DFT calculations of 8 revealed substantial mixing between the Fe 3d(xz/yz) and NO(π*) orbitals in the β-manifold, similar to the bonding scheme described above for 1-acacPhF3(NO). In these situations, Berto and Lehnert argue that the NO− ligand behaves as a strong π-donor, which lowers the effective nuclear charge of the Fe(III) center.

Complex 1-acacPhF3(NO) serves as an approximate model of the ferric–superoxo intermediate in the Dke1 mechanism. On the basis of DFT calculations, Diebold et al. have proposed that the superoxo group electrophilically attacks the acac HOMO to yield a peroxo bridge between Fe and the central C atom of the acac ligand.9 This crucial step in the catalytic cycle would be facilitated by charge donation from the substrate HOMO to the Fe3+ center in the initial Fe/O2 adduct, as likely occurs in the mechanism of extradiol catechol dioxygenases. Yet our calculations indicate that the acacPhF3 HOMO in 1-acacPhF3(NO) is essentially nonbonding with respect to the Fe-NO unit, and the amount of unpaired-spin density on the carbons atoms of the acacPhF3 ligand is negligible for both 1-acacPhF3(NO) and its ferrous precursor.

4.DISCUSSION

This manuscript has described the reactivity of the Fe(II) β-diketonato complexes, [Fe2+(LN3)(acacX)] (LN3 = Me2Tp, Ph2Tp, PhTIP), with O2 and NO under various reaction conditions. On the basis of our observations, we propose the mechanistic framework shown in Scheme 2. With the exception of 1-acacF6 , complexes in the 1-acacX series readily react with O2 in toluene to produce dark green intermediates (4-acacX) that are only stable at temperatures less than −60 °C. A combination of spectroscopic and computational results suggest that the 4-acacX intermediates consist of two [Fe3+(Me2Tp)-(acacX)]+ units linked by a trans µ-1,2-peroxide ligand (Figure 4). Given the generally accepted pattern of Fe/O2 chemistry,40 it is reasonable to assume that initial O2 binding generates an iron(III)-superoxo intermediate (not observed) that quickly reacts with a second 1-acacX equivalent to form the diferric-peroxide intermediate, 4-acacX. In MeCN, reaction of some 1-acacX complexes with O2 ultimately yields linear trinuclear complexes (5-acac and 5-acacPhF3 ) featuring four bridging carboxylates and two O(H) ligands (Supporting Information, Figure S4), as demonstrated previously by Kitajima and co-workers.10 It is not certain if the formation of the triiron species proceeds via breakdown of the corresponding diiron(III)-peroxo intermediate or whether another mechanism is operative. While 4-acac is indeed observed during the oxygenation of 1-acac in MeCN (Figure 3), 4-acacX intermediates are not evident in the 1-acacX→5-acacX conversions of the remaining complexes, although this result does not rule out transient formation of the green intermediates in these cases. Limberg has suggested that cleavage of the acacX ligand in Kitajima’s model (and in our systems, by extension) may be due to trace amounts of H2O in MeCN, which could hydrolyze the acacX ligand following oxidation of the Fe center.11

Scheme 2.

Compared to the 1-acacX series, Fe(II)-acacX complexes with Ph2Tp or PhTIP supporting ligands (2-acacX and [3-acacX ]+, respectively) exhibit dramatically diminished reactivity toward O2. Complexes with β-diketonato ligands are stable in oxygenated solutions at room temperature for several hours or days, regardless of solvent. We initially assumed that this inert behavior was due to the steric bulk of the phenyl substituents, which might be expected to block O2 coordination the Fe center. Yet this hypothesis is not consistent with the facile formation of {FeNO}7 adducts upon exposure of the 2-acacX and [3-acacX]+ complexes to NO, proving that formation of an Fe/O2 species is sterically feasible for the Ph2Tp- and TIP-based complexes. However, the size of the Ph groups likely prevents the second step in the pathway to 4-acacX, that is, formation of the diiron intermediate via reaction with a second Fe(II) complex (Scheme 2). Our DFT model of 4-acac possesses a high degree of steric crowding even with relatively small methyl substituents on the pyrazole rings (Figure 4). The presence of phenyl rings at these positions would undoubtedly lead to severe steric clashes between opposing Ph2Tp (or PhTIP) ligands, thereby prohibiting formation of the analogous 4-acacX species.

The scenario illustrated in Scheme 2 requires the reaction equilibrium of the first step (i.e., O2 binding) to lie far to the side of Fe(II) + O2, since the putative iron(III)-superoxo adduct is never observed. Indeed, a number of computational studies have demonstrated that the reversible transfer of one electron from a mononuclear nonheme Fe(II) center to O2 is endergonic by approximately 5–10 kcal/mol.9,41 In our Me2Tp systems, the uphill nature of this initial step is overcome by the thermodynamic favorability of the second step, which “pulls” the entire process forward to 4-acacX. However, when this second step is hindered because of steric reasons, the ferrous complexes are rendered much less reactive toward O2, as observed for the 2-acacX and [3-acacX]+ series.

Obviously, the protein environment surrounding the Fe center in Dke1 prevents formation of a diiron-peroxo intermediate like 4-acacX. Instead, the enzymatic mechanism likely involves formation of a peroxy bridge between Fe and acac following initial formation of an iron(III)-superoxo species. One would therefore expect the Ph2Tp and PhTIP supporting ligands, which prevent dimerization, to be ideal scaffolds for reproducing the catalytic activity of Dke1. Instead, only 2-acacX complexes with activated dialkyl malonate anions (2-acacOMe and 2-acacPhmal) react with O2 to give oxidized products. Since these complexes are not capable of forming diiron(III)-peroxo species like the Me2Tp-based complexes, the dioxygenolytic cleavage mechanism likely replicates the mechanism proposed by Diebold et al. for the enzyme.9 However, even when dioxygenase activity is observed in our synthetic models, the rate of reaction is orders of magnitude slower than the rate of the enzyme with its natural substrate (kcat = 6.5 s−1 for acetylacetone). Remarkably, Dke1 is capable of oxidizing unactivated substrates like acacF3 and acacPhF3 at measurable rates of 5.3 × 10−3 and 5.2 × 10−5 s−1;8 by contrast, the corresponding synthetic complexes are stable in air for days.

The lackluster O2 reactivity exhibited by complexes in the 2-acacX and [3-acacX]+ series highlights the obstacles Dke1 must overcome to oxidize β-diketone substrates. As noted above, formation of the initial Fe/O2 adduct has been shown to be endergonic in most nonheme Fe enzymes studied to date; therefore, enzymes rely on a favorable second-step to move the catalytic cycle forward. In the extradiol catechol dioxygenases, this process is facilitated by (partial or total) electron transfer from the bound catecholate substrate to Fe, resulting in a putative superoxo-Fe(II)-semiquinone intermediate. As demonstrated by Siegbahn, the radical character on the aromatic substrate lowers the barrier to peroxide formation.41b However, this strategy is not feasible in the case of Dke1, which involves oxidation of an aliphatic substrate. Our crystallographic and computational studies of 1-acacX(NO) adducts, reasonable models of the putative iron-superoxo intermediate in Dke1, failed to detect any significant radical character on the carbon backbone of the acacX ligands. Thus, there appears to be an intrinsically large barrier to formation of the key alkylperoxo intermediate. The protein environment in Dke1 probably plays an important role in significantly lowering the barrier to O2 reduction. This conclusion is consistent with computational and mutagenesis studies performed by Straganz and co-workers, who have demonstrated that changes in second-sphere residues (both hydrophilic and hydrophobic) significantly alter the rate of acetylacetone oxidation.42 Nearby residues may function as acid/base catalysts, as is the case for ring-cleaving dioxygenases.43 In a recent computational study, Christian et al. indicated that the barrier to alkylperoxo formation is lowered by simultaneous transfer of a proton to the proximal O-atom of the peroxo bridge.44 While this study focused on the extradiol catechol dioxygenases, it is possible that a similar mechanism is operative in Dke1. The incorporation of these subtle second-sphere effects poses a challenge to the development of synthetic complexes capable of displaying Dke1-type reactivity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Brian Bennett for generously allowing us to perform EPR experiments at the National Biomedical EPR Center (supported by NIH P41 Grant EB001980), and Dr. Thomas C. Brunold at UW-Madison for access to his MCD instrument. A.T.F. also thanks Marquette University and the National Science Foundation (CAREER CHE-1056845) for generous financial support.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

1H NMR data for 1-acacOMe and 2-acacOMe, absorption spectra of 1-acacX complexes under various reaction conditions, crystallographic structures of 5-acacPhF3 and Fe(Ph2Tp)2, MCD spectra of 4-acac, metric parameters for DFT-optimized models and TD-DFT results, absorption and EPR spectra of Fe/NO adducts, and crystallographic data in CIF format. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gibson DT, Parales RE. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:236–243. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Parales RE, Haddock JD. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004;15:374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Bugg TDH, Lin G. Chem. Commun. 2001;11:941–953. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bugg TDH. Curr. Op. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:550–555. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:186–193. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Titus GP, Mueller HA, Burgner J, Córdoba SRd, Penalva MA, Timm DE. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:542–546. doi: 10.1038/76756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vaillancourt FH, Bolin JT, Eltis LD. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:241–267. doi: 10.1080/10409230600817422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Machonkin TE, Doerner AE. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8899–8913. doi: 10.1021/bi200855m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Machonkin TE, Holland PL, Smith KN, Liberman JS, Dinescu A, Cundari TR, Rocks SS. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2010;15:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yin Y, Zhou NY. Curr. Microbiol. 2010;61:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straganz GD, Glieder A, Brecker L, Ribbons DW, Steiner W. Biochem. J. 2003;369:573–581. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Leitgeb S, Nidetzky B. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:1180–1186. doi: 10.1042/BST0361180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leitgeb S, Straganz GD, Nidetzky B. Biochem. J. 2009;418:403–411. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diebold AR, Neidig ML, Moran GR, Straganz GD, Solomon EI. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6945–6952. doi: 10.1021/bi100892w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straganz GD, Hofer H, Steiner W, Nidetzky B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12202–12203. doi: 10.1021/ja0460918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straganz GD, Nidetzky B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12306–12314. doi: 10.1021/ja042313q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diebold AR, Straganz GD, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15979–15991. doi: 10.1021/ja203005j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitajima N, Amagai H, Tamura N, Ito M, Morooka Y, Heerwegh K, Penicaud A, Mathur R, Reed CA, Boyd PDW. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:3583–3584. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siewert I, Limberg C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7953–7956. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park H, Baus JS, Lindeman SV, Fiedler AT. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:11978–11989. doi: 10.1021/ic201115s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malbosc F, Chauby V, Serra-Le Berre C, Etienne M, Daran JC, Kalck P. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001:2689–2697. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitajima N, Fujisawa L, Fujimoto C, Moro-oka Y, Hashimoto S, Kitagawa T, Toriumi K, Tatsumi K, Nakamura A. J. Am. Chem Soc. 1992;114:1277–1291. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunz PC, Klaeui W. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2007;72:492–502. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009;42:339–341. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811041161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neese F. ORCA - An ab initio, Density Functional and Semi-empirical Program Package, version 2.8. Bonn, Germany: University of Bonn; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;84:4524–4529. [Google Scholar]; (b) Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Schafer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;97:2571–2577. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schafer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;100:5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Stratmann RE, Scuseria GE, Frisch MJ. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;109:8218–8224. [Google Scholar]; (b) Casida ME, Jamorski C, Casida KC, Salahub DR. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:4439–4449. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bauernsch-mitt R, Ahlrichs R. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;256:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Hirata S, Head-Gordon M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:291–299. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hirata S, Head-Gordon M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;302:375–382. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laaksonen L. J. Mol. Graphics. 1992;10:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(92)80007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, Vanrijn J, Verschoor GC. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984:1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehn MP, Fujisawa K, Hegg EL, Que L., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7828–7842. doi: 10.1021/ja028867f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The pKa of dimethyl malonate is 16 in DMSO, while the corresponding value for imidazole is 18.6. For reference, the pKa of acetylacetone is 13.6 in DMSO. Although the absolute pKa values measured in DMSO and acetonitrile are expected to be quite different, the relative acidities are likely similar in the two solvents. Values were obtained from Izutsu K. Acid-Base Dissociation Constants in Dipolar Aprotic Solvents; Blackwell Scientific. Oxford, U.K: Publications; 1990.

- 27.Limberg et al. also observed formation of the Fe(Me2Tp)2 complex upon reaction of their Dke1 model with O2. See reference 11

- 28.(a) Kitajima N, Tamura N, Amagai H, Fukui H, Moro-oka Y, Mizutani Y, Kitagawa T, Mathur R, Heerwegh K, Reed CA, Randall CR, Que L, Jr, Tatsumi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9071–9085. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim K, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4914–4915. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunold TC, Tamura N, Kitajima M, Moro-oka Y, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5674–5690. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bou-Abdallah F, Chasteen ND. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.β-diketonate ligands haven been shown to bridge metal centers in a µ-1,1 fashion. However, utilization of the µ-1,1 coordination mode in 4-acac would result in coordinatively saturated Fe centers incapable of binding O2

- 32.(a) Sinnecker S, Neese F, Noodleman L, Lubitz W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2613–2622. doi: 10.1021/ja0390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Binning RC, Bacelo DE. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:716–723. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.This disparity between 4DFT-acac and 7 with respect to Fe-Operoxo distances is not due to deficiencies in the DFT methodologies, since our “control” calculation of 7 provided bond distances consistent with the reported crystal structure. In addition, steric crowding is only partially responsible for the elongated Fe-Operoxo bonds in 4DFT-acac, since replacement of the Tp methyl groups with hydrogen shortens the Fe-Operoxo bonds by a mere 0.02 Å

- 34.The binding of O2 is exothermic for both 7 (ΔH = −21.2 kcal/ mol) and 4-acac (ΔH = −9.3). As expected, the corresponding entropy terms are positive in both cases: +101 cal/K for 7 and +110 cal/K for 4-acac

- 35.Enemark JH, Feltham RD. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1974;13:339–406. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Brown CA, Pavlosky MA, Westre TE, Zhang Y, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem Soc. 1995;117:715–732. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chiou YM, Que L. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:3270–3278. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hauser C, Glaser T, Bill E, Weyhermuller T, Wieghardt K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4352–4365. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wasinger EC, Davis MI, Pau MYM, Orville AM, Zaleski JM, Hedman B, Lipscomb JD, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:365–376. doi: 10.1021/ic025906f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jackson TA, Yikilmaz E, Miller AF, Brunold TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8348–8363. doi: 10.1021/ja029523s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) McCleverty JA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:403–418. doi: 10.1021/cr020623q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Berto TC, Hoffman MB, Murata Y, Landenberger KB, Alp EE, Zhao JY, Lehnert N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16714–16717. doi: 10.1021/ja111693f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The observed disorder in the FeNO unit is likely the result of crystal packing. In solution, the NO ligand is free to rotate, and the observed EPR parameters reflect an averaging of possible orientations

- 39.In the DFT model of 1-acacPhF3(NO) described in the text, the NO ligand adopts the dominant orientation found in the X-ray structure. The alternative model based on the minor structure was also examined with DFT. The two models are essentially isoenergetic (ΔE = 0.8 kcal/mol, within the margin of error) and the electronic structures are nearly identical

- 40.Mukherjee A, Cranswick MA, Chakrabarti M, Paine TK, Fujisawa K, Muenck E, Que L., Jr Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3618–3628. doi: 10.1021/ic901891n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Davis MI, Wasinger EC, Decker A, Pau MYM, Vaillancourt FH, Bolin JT, Eltis LD, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11214–11227. doi: 10.1021/ja029746i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bassan A, Borowski T, Siegbahn PE. M. Dalton Trans. 2004:3153–3162. doi: 10.1039/B408340G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Straganz GD, Diebold AR, Egger S, Nidetzky B, Solomon EI. Biochemistry. 2010;49:996–1004. doi: 10.1021/bi901339n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brkic H, Buongiorno D, Ramek M, Straganz G, Tomic S. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2012;17:801–815. doi: 10.1007/s00775-012-0898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipscomb JD. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christian GJ, Ye SF, Neese F. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1600–1611. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.