Abstract

Purpose

Some evidence suggests that risk reduction programming for sexual risk behaviors (SRB) has been minimally effective, emphasizing a need for research on etiological and mechanistic factors that can be addressed in prevention and intervention programming. Childhood sexual and physical abuse have been linked with SRB among older adolescents and emerging adults; however, pathways to SRB remain unclear. This study adds to the literature by testing a model specifying that traumatic intrusions following early abuse may increase risk for alcohol problems, which in turn, may increase the likelihood of engaging in various types of SRB.

Methods

Participants were 1169 racially-diverse college students (72.9% female; 37.6% Black/African-American; 33.6% White) who completed anonymous questionnaires assessing child abuse, traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and sexual risk behavior.

Results

The hypothesized path model specifying that traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems account for associations between child abuse and several aspects of SRB was a good fit for the data; however, for men, stronger associations emerged between physical abuse and traumatic intrusions and between traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems, while for women, alcohol problems were more strongly associated with intent to engage in risky sex.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the role of traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems in explaining paths from childhood abuse to SRB in emerging adulthood and suggest that risk reduction programs may benefit from an integrated focus on traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and SRB for individuals with abuse experiences.

Implications and Contribution

This study provides support for a pathway from childhood abuse to risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood that operates through traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems. Risk reduction programs that employ an integrated focus on traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and risky sexual behavior may be more effective for individuals with abuse histories.

Reducing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancies among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. is a top priority for Healthy People 2020 (1). Adolescents and emerging adults are especially likely to report sexual risk behavior (SRB) including sex with multiple partners, sex while using substances, and inconsistent condom use (e.g., 2). Such behaviors are associated with HIV infection, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unintended pregnancy (2,3). Nearly half of the 19 million new STIs each year are among young people aged 15–24 years (3). Understanding factors that may increase the likelihood of SRB during emerging adulthood is an important public health goal.

Adverse childhood experiences, including a history of child sexual and physical abuse, may increase the likelihood of engaging in SRB among emerging adults (4,5,6,7). Most studies examining associations between child abuse and adolescent/emerging adult sexual behavior have focused on the long-term effects of child sexual abuse (CSA) in female sample (4,5,6) and found that those with CSA histories report more lifetime sexual partners (4,6) and more episodes of unprotected sex (6) compared to women without such histories. Further, among children with documented maltreatment histories who were followed into adulthood, the odds of prostitution and HIV were more than twice the odds of prostitution and HIV among non-abused matched controls (7). Increased exposure to adverse childhood experiences (including sexual and physical abuse) have been associated with increased risk of STIs (8). Although factors like emotion dysregulation (4) and traumagenic dynamics (6,9) have been posited to explain associations between child abuse and SRB, these explanations often do not consider contextual factors, such as alcohol use, that may increase risk for SRB.

Alcohol use and problems, which are highly prevalent among college students (10), have been linked with both childhood adversity (5) and SRB (11). Researchers have suggested that alcohol use among adult victims of child abuse may “set the stage” for SRB (12), perhaps by aiding victims in overcoming sexual inhibition and increasing comfort in sexual situations (13). As reviewed by Cooper (14), alcohol myopia theory suggests that alcohol may increase SRB in ambivalent situations where there are strong reasons for and against having sex (e.g., increase positive affect vs. avoid STIs). In naturalistic settings, acute alcohol intoxication has been associated with increased intentions to engage in SRB (15) and reduced assertiveness in response to requests for unprotected sex (e.g., 16). In clinical settings, alcohol and drug dependence symptoms have been shown to mediate associations between child abuse and both intoxicated and unprotected sex (17). Furthermore, one study found that 41% of college women and 36% of college men report negative alcohol-related sexual consequences including unprotected sex, having sex with someone they would not have if sober, and unwanted sex (18). However, stable individual differences in drinking have not been found to fully explain SRB (for review see 14), and risk reduction programs targeting alcohol use/problems and SRB have been minimally effective in reducing SRB (e.g., 19). Thus, there may be value in continued research on etiological and mechanistic factors that may increase risk for alcohol problems and SRB.

A significant period of time may have elapsed between child abuse and more temporally proximal alcohol problems and SRB, raising questions about whether other processes occurring in the interim may contribute to the development of risk behaviors and serve as an effective target for interventions. A number of theories have been proposed to explicate how early sexual and physical abuse may lead to adult risk behaviors including the development of traumagenic dynamics (9) and emotion dysregulation (4). Traumagenic dynamics theory postulates that sexual abuse shapes beliefs that sex can be used for affection or rewards (9), while emotion regulation theory suggests that sex may briefly relieve negative affect by increasing positive emotions and feelings of intimacy (see 4). Although posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most common and impairing conditions associated with early physical and sexual abuse (20), surprisingly few studies have examined whether trauma symptoms explain the relationship between early abuse and alcohol problems and SRB in early adulthood. Those with abuse histories may use alcohol to cope with distressing trauma symptoms or the traumagenic outcomes of abuse (e.g., feelings of betrayal or powerlessness). Some studies have found that trauma symptoms mediate the association between childhood sexual abuse and alcohol use among adult women (e.g., 21) without considering the role of SRB or other types of child abuse. Other studies of highly trauma-exposed and socioeconomically disadvantaged women have documented associations between PTSD and SRB (e.g., 22) without considering the role of alcohol use/problems or child abuse.

In summary, although emerging adulthood is a period when alcohol use/problems and SRB peak (23), and there is evidence that early child abuse may increase risk for both outcomes (e.g., 6), there is a dearth of information on associations between child abuse, traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and SRB among male and female college students. The current study used data from a large sample of ethnically diverse male and female college students to test a path model from child physical or sexual abuse to various types of SRB that operates through traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems. Given that numerous studies have suggested that alcohol use/problems may increase the likelihood of SRB (e.g., 12), we hypothesized a directional relationship between these variables such that alcohol problems preceded SRB in the path model. To examine whether this temporal sequence best fit the data, we tested two alternate models: the first specified concurrent alcohol problems and SRB and the second specified SRB leading to alcohol problems. Given that much of the research to date on child abuse and risky sexual behavior has focused on women (4,5,6), we examined whether the hypothesized path model fit the data well for both men and women.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1169 racially-diverse college students (72.9% female) at a large, public urban Southeastern university where the majority of the student body (64%) is ethnic minority. More than 90% of students receive some financial aid and more than 50% receive needs-based grants or scholarships. The average age was 20.7 (SD = 4.65). Of the sample, 37.6% (n = 439) were Black/African American, 33.6% (n = 393) were White, and 14.5% (n = 169) were Asian/Asian American.

Measures

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ;24)

The CTQ is a 28-item measure of Likert-type questions designed to screen for child physical, sexual, and emotional abuse as well as physical and emotional neglect while growing up. The physical (5 items) and sexual (5 items) abuse subscales were the focus of the present study. A sample physical abuse item is “I got hit or beaten so badly that it was noticed by someone like a teacher, neighbor, or doctor” and a sample sexual abuse item is “Someone tried to touch me in a sexual way or tried to make me touch them.” Response options range from 1 = never true to 5 = very often true, and are summed to create continuous physical and sexual abuse severity scores, which were used in path analyses. Cut scores of 6 or above for CSA and 8 or above for CPA were used to estimate the prevalence of low/moderate abuse (24). Numerous investigations attest to the reliability and validity of scores on this measure (e.g., 25). Cronbach’s alpha was .94 for the sexual abuse subscale and .82 for the physical abuse subscale.

Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; 26)

The IDAS is a 64-item measure of depression and anxiety symptoms experienced during the previous two weeks. Participants respond to each Likert-type item on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely. The IDAS has excellent internal consistency and reliability and good psychometric properties (27). The 4-item Traumatic Intrusions scale (e.g., “I had disturbing thoughts about something bad that happened to me”), which correlates strongly with clinical diagnoses of PTSD (27), was used here. Cronbach’s alpha for the Traumatic Intrusions scale was .86.

Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; 28)

The RAPI is a 23-item measure of problems experienced because of alcohol use in the past 6 months. A sample item is “I went to work or school high or drunk.” Participants respond to each Likert-type item on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (more than 10 times). The RAPI has shown good reliability, internal consistency, and validity with young adults (28). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .96.

Sexual Risk Survey (SRS; 29)

The SRS is a 23-item self-report scale that measures the number of times participants engaged in various types of SRB (e.g., sex with someone they just met, unprotected sex) and the number of partners with whom they engaged in such behaviors over the previous 6 months. The SRS contains 5 subscales assessing risky sex with uncommitted partners (8 items; e.g., “Had sex with a partner I didn’t trust”), risky sex acts (5 items; e.g., “Had vaginal sex without a condom”), impulsive sex (5 items; e.g., “Had sex with an acquaintance”), intent to engage in risky sex (2 items; e.g., “Intended to engage in sex”), and risky anal sex acts (3 items; e.g., “Had anal sex without a condom”). Responses are summed to create subscale scores. In the initial validation study with a college student sample, scores on the SRS were internally consistent (alpha = .88) and stable over a 2-week period (r = .93) (29). Cronbach’s alphas were .90 for risky sex with uncommitted partners, .84 for risky sex acts, .78 for impulsive sex, .79 for intent to engage in risky sex, and .72 for risky anal sex acts.

Procedures

All procedures and materials for the study were approved by the institutional review board for human subjects research. Participants were recruited from an online departmental research participation pool for a study of “personality and behavior” and received credit in partial fulfillment of a research requirement for an introductory psychology class. All questionnaires were completed electronically.

Analytic Plan

We initially examined descriptive information and bivariate correlations and then fit a path model in Mplus version 6.0 (30). We fit a model specifying that traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems serve as mediators in the path from child abuse to various types of SRB. The final path model included two exogenous variables, child sexual abuse and child physical abuse, and seven endogenous variables: traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, sex with uncommitted partners, risky sex acts, impulsive sex, intent to engage in risky sex, and risky anal sex. Model fit was evaluated using Kline’s recommendation that the model chi-square statistic be non-significant (31) and Hu and Bentler’s recommendations that the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) be greater than .95, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) be less than or equal to .06, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) be less than .08 (32). We also examined the significance of the indirect path from child abuse through traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems to each form of SRB using the MODEL INDIRECT command in Mplus. We tested model invariance across men and women using multigroup analyses that first tested the fit of an unconstrained model across gender and then tested the fit of a constrained model and used the chi-square difference test to examine whether model fit significantly worsened. To examine whether the hypothesized temporal ordering provided the best fit to these data, we conducted sensitivity analyses examining the fit of two alternate models: the first tested a model with alcohol problems and SRB co-occurring and the second tested a model with alcohol problems resulting from SRB. Finally, because our sample contained a large proportion of African American students, we examined African American race (versus other) as a covariate in models.

Results

Descriptive information is presented overall and by gender in Table 1. Skewness for the SRB variables ranged from 1.1 to 3.8; a base-10 log transformation was applied to the four subscales with skewness between 1.1 and 2.9; an inverse transformation was applied to the fifth subscale, which had a skewness value of 3.8. Approximately 32% (n = 374) of participants screened positive for CSA and 41.5% (n = 483) screened positive for physical abuse. The sexual abuse item “Someone tried to touch me in a sexual way, or tried to make me touch them” and the physical abuse item “I was punished with a belt, a board, a cord, or some other hard object” (corporal punishment) were the most frequently endorsed for each type of abuse. Men had more physical abuse, alcohol problems, sex with uncommitted partners, impulsive sex, intent to engage in risky sex, and risky anal sex compared with women. Correlations among the study variables are presented for women and men in Table 2. Significant, positive bivariate associations emerged between both forms of child abuse, traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and most aspects of SRB; there was no association between CSA and risky sex acts or risky anal sex for men and no association between CPA and risky sex acts for either gender. Further, traumatic intrusions were not associated with risky anal sex for either gender.

Table 1.

Means (Standard Deviations) among Study Variables Overall and By Gender

| Overall | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | 7.30 (4.4) | 7.45 (4.19) | 7.24 (4.4) | .45 |

| CPA | 8.16 (3.9) | 8.83 (4.1) | 7.92 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Traumatic Intrusions | 7.70 (3.7) | 7.56 (3.5) | 7.76 (3.8) | .55 |

| Alcohol Problems | 30.1 (11.3) | 32.5 (12.7) | 29.22 (10.6) | <.001 |

| Sex w/ unc. partners | 4.84 (6.50) | 5.85 (7.79) | 4.46 (5.91) | <.001 |

| Risky sex acts | 4.0 (4.3) | 3.73 (4.30) | 3.96 (4.31) | .41 |

| Impulsive sex | 2.69 (3.25) | 3.92 (4.09) | 2.23 (2.74) | <.001 |

| Intent of risky sex | .57 (1.36) | 1.40 (2.04) | .27 (.82) | <.001 |

| Risky anal sex | .57 (1.59) | .78 (1.93) | .50 (1.43) | <.01 |

Note: CSA = Child Sexual Abuse, CPA = Child Physical Abuse, Sex w/ unc. Partners = sex with uncommitted partners;

p <.05,

p <.01,

p<.001

Table 2.

Correlations among Study Variables for Women/Men

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSA | -- | 53***/.77*** | .31***/.45*** | .31***/.48** | .09**/.15** | .12***/.07 | .08*/.21*** | .05/.23*** | .10**/.10 |

| 2. CPA | -- | .36***/.40*** | .40***/.46*** | .13***/.19*** | .05/.07 | .09**/.17*** | .03/.19** | .12***/.12* | |

| 3. Traumatic Intrusions | -- | .43***/.54*** | .20***/.32*** | .13*/.16*** | .16**/.31*** | .09/.28*** | .04/.03 | ||

| 4. Alcohol Problems | -- | .25***/.32*** | .14***/.24*** | .29***/.33*** | .25***/.34*** | .11**/.17** | |||

| 5. Unc. partners | -- | .52***/.59*** | .62***/.70*** | .32***/.59*** | .21***/.34*** | ||||

| 6. Risky sex acts | -- | .31***.45*** | .16***/.39*** | .21***/.27*** | |||||

| 7. Impulsive sex | -- | .45***/.67*** | .15***/.21*** | ||||||

| 8. Intent of risky sex | -- | .05/.12* | |||||||

| 9. Risky anal sex | -- |

Note: CSA = Child Sexual Abuse, CPA = Child Physical Abuse, Unc. partners = sex with uncommitted partners;

p <.05,

p <.01,

p<.001

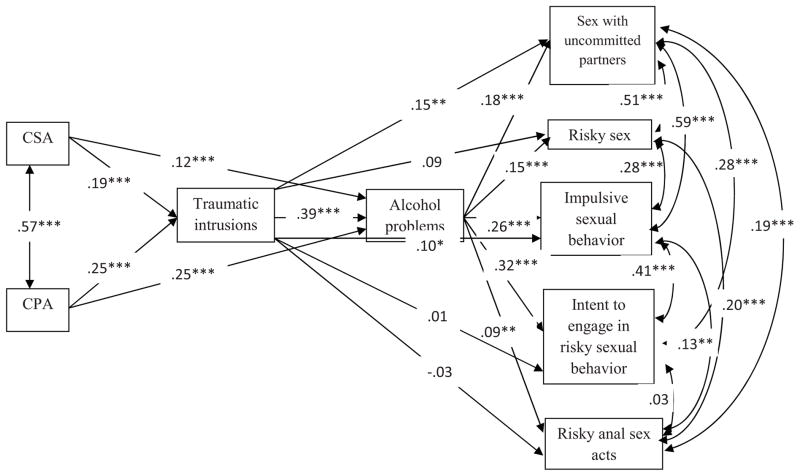

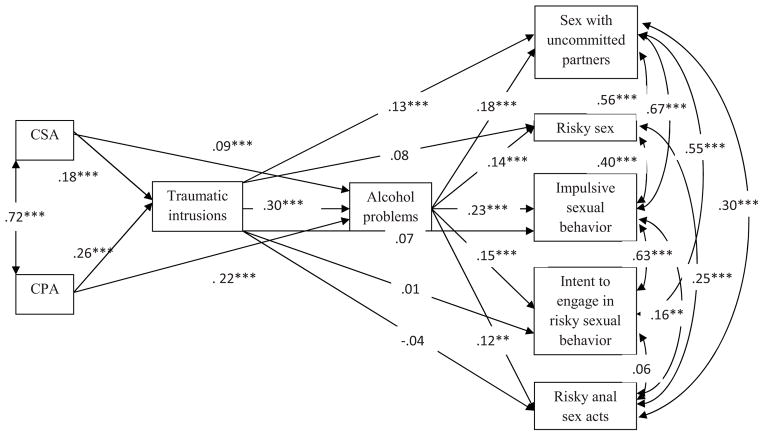

The unconstrained path model specifying relationships between CSA, CPA, traumatic intrusions, alcohol problems, and each of the 5 risky sex subscales was an excellent fit for these data, χ2(2) = 0.39, p = 0.82, RMSEA = 0.001; SRMR = 0.003; CFI = 1.0. A model constraining paths across men and women also fit the data well, χ2(26) = 58.4, p <.001, RMSEA = 0.046; SRMR = 0.05; CFI = 0.98, but was a significantly worse fit, χ2Δ=58.01, dfΔ = 24. Standardized path coefficients for women and men are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively; all hypothesized paths were significant and positive. All direct and indirect effect estimates and standard errors (SEs) are presented in Table 3. As noted in the last column of Table 3, there were significant differences between women and men in the direct paths from CPA to traumatic intrusions, traumatic intrusions to alcohol problems, and alcohol problems to intent to engage in risky sex. As noted at the bottom of Table 3, the indirect paths from both forms of abuse through traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems to each form of SRB were significant for men and women.

Figure 1.

Path Model Predicting Alcohol Problems and Risky Sexual Behavior for Women

Figure 2.

Path Model Predicting Alcohol Problems and Risky Sexual Behavior for Men

Table 3.

Direct and Indirect Estimates for Final Model

| Direct | Women Estimate (SE) |

Men Estimate (SE) |

Difference Estimate (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA➝ Traumatic Intrusions | .19 (.05)*** | .18 (.05)*** | .19 (.12) |

| CPA➝ Traumatic Intrusions | .25 (.04)*** | .26 (.05)*** | .25 (.13)* |

| CSA➝ Alcohol Problems | .12 (.04)*** | .09 (.03)*** | .24 (.28) |

| CPA➝ Alcohol Problems | .25 (.04)*** | .22 (.03)*** | −.04 (.28) |

| CSA➝ Sex w unc. partners | −.05 (.04) | −.04 (.03) | −.01 (.02) |

| CSA➝ Risky sex acts | .06 (.04) | .05 (.03) | −.02 (.01) |

| CSA➝ Impulsive sex | −.01 (.04) | −.01 (.03) | .007 (.009) |

| CSA➝ Intent of risky sex | .02 (.04) | .01 (.02) | .008 (.006) |

| CSA➝ Risky anal sex | .03 (.04) | .03 (.04) | .004 (.005) |

| CPA➝ Sex w unc. partners | .02 (.04) | .02 (.03) | .01 (.01) |

| CPA➝ Risky sex acts | −.08 (.04)* | −.08 (.04) | .007 (.01) |

| CPA➝ Impulsive sex | −.04 (.04) | −.03 (.03) | .001 (.009) |

| CPA➝ Intent of risky sex | −.08 (.04)* | −.04 (.02) | .01 (.006) |

| CPA➝ Risky anal sex | .06 (.04) | .07 (.04) | −.001 (.005) |

| Tr. Int➝ Alcohol problems | .30 (.05)*** | .39 (.06)*** | .57 (.27)* |

| Tr. Int➝ Sex w unc. partners | .15 (.05)** | .13 (.04)** | .01 (.02) |

| Tr. Int➝ Risky sex acts | .09 (.05) | .08 (.05) | −.005 (.01) |

| Tr. Int➝ Impulsive sex | .10 (.05) | .07 (.04) | .004 (.01) |

| Tr. Int➝ Intent of risky sex | .01 (.05) | .01 (.02) | .001 (.008) |

| Tr. Int➝ Risky anal sex | −.03 (.05) | −.04 (.05) | .001 (.007) |

| Alc. Prob ➝ Sex w unc. partners | .18 (.04)*** | .18 (.04)*** | .001 (.003) |

| Alc. Prob ➝ Risky sex acts | .12 (.05)*** | .14 (.04)** | .004 (.003) |

| Alc. Prob ➝ Impulsive sex | .26 (.04)*** | .23 (.03)*** | .001 (.003) |

| Alc. Prob ➝ Intent of risky sex | .32 (.04)*** | .15 (.02)*** | .003 (.002)* |

| Alc. Prob ➝ Risky anal sex | .09 (.01)** | .12 (.04)** | .001 (.002) |

| Indirect Effects | |||

| CSA ➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Sex w unc. partners | .024 (.008)** | .018 (.006)** | -- |

| CSA ➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Risky sex acts | .016 (.006) | .013 (.005)* | -- |

| CSA ➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝Impulsive sex | .030 (.01)*** | .023 (.007)** | -- |

| CSA ➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Intent of risky sex | .040 (.013)*** | .015 (.005)** | -- |

| CSA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Risky anal sex | .011 (.03)* | .011 (.005)* | -- |

| CPA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Sex w unc. partners | .030 (.009)*** | .026 (.008)*** | -- |

| CPA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Risky sex acts | .020 (.007)** | .020 (.007)** | -- |

| CPA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Impulsive sex | .040 (.011)*** | .034 (.009)*** | -- |

| CPA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Intent of risky sex | .052 (.013)*** | .022 (.006)*** | -- |

| CPA➝ Tr. Int➝ Alc. Prob➝ Risky anal sex | .015 (.006)* | .017 (.007)* | -- |

|

| |||

| Variance (R2) | |||

| Traumatic Intrusions | .16 (.03)*** | .19 (.05)*** | -- |

| Alcohol Problems | .25 (.03)*** | .37 (.05)*** | -- |

| Sex w/ unc. partners | .08 (.02)*** | .13 (.04)*** | -- |

| Risky sex acts | .04 (.02)** | .06 (.03)* | -- |

| Impulsive sex | .09 (.02)*** | .12 (.04)*** | -- |

| Intent of risky sex | .07 (.02)*** | .12 (.03)*** | -- |

| Risky anal sex | .02 (.009)* | .03 (.02)* | -- |

Note: CSA= Child sexual abuse; CPA = Child physical abuse; Tr. Int = Traumatic Intrusions; Alc. Prob = Alcohol Problems;

p <.05,

p <.01,

p<.001

Sensitivity analyses

A model specifying co-occurring alcohol problems and SRB rather than a directional relationship between alcohol problems and SRB was a poorer fit for these data, χ2(12) = 139.6, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.09; SRMR = 0.05; CFI = 0.94. A model specifying alcohol problems following SRB was an unacceptable fit for these data, χ2(26) = 1490.4, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.31; SRMR = 0.17; CFI = 0.29. We also added African American race to the model as a predictor of sexual and physical abuse; model fit declined minimally, χ2(42) = 139.3, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.056; CFI = 0.96, and African American race (versus other) was positively associated with CSA (women = .10, p <.001; men = .11, p <.001) and CPA (women = .15, p <.001; men = .14, p <.001) in men.

Discussion

The current study is the first, of which we are aware, to test a path model specifying that traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems help to explain relationships between child physical and sexual abuse and various forms of SRB in a sample of male and female college students. Unique aspects of this study included a racially diverse sample of male and female college students and assessment of sexual and physical abuse experiences as well as a variety of SRB in relation to both traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems. The hypothesized model fit the data well and findings suggested that traumatic intrusions and (past 6-month) alcohol problems may explain the link between child abuse and SRB. More specifically, child abuse victims with traumatic intrusions who had higher levels of alcohol problems were more likely to report engaging in various types of SRB including sex with uncommitted partners, risky sex acts, impulsive sex, intentions to engage in risky sex, and risky anal sex. Results of constrained models suggested gender differences in the strength of relationships such that men had stronger associations between CPA and traumatic intrusions and between traumatic intrusions and alcohol problems whereas women had stronger associations between alcohol problems and intent to engage in risky sex.

Rates of reported child sexual abuse in our sample (32%), while high, fall within the range reported in the literature for college student samples (for a review, see 33). However, the prevalence of reported child physical abuse (41.5%) is higher than the prevalence typically reported with college samples (e.g., 34). It is possible that higher rates of childhood physical abuse were, in part, due to characteristics of our sample. The most commonly endorsed item on the physical abuse subscale relates to corporal punishment (“I was punished with a belt, a board, a cord, or some other hard object”), and research indicates that African American race and low socioeconomic status are risk factors for corporal punishment (35). Findings are consistent with research suggesting that child abuse victims are more likely to have alcohol problems and engage in SRB (4) but suggest that these relationships are not specific to sexual abuse as some prior work suggests (6). Findings also support research from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study suggesting that the long-term health consequences of childhood sexual abuse are similar for men and women (36). However, in our study, physical abuse had more of an impact on traumatic intrusions and traumatic intrusions had a stronger impact on alcohol problems for men than for women. Alcohol problems were more strongly associated with intent to engage in risky sex for women than for men. Additional research is necessary to better understand the observed gender differences; if findings are replicated, it may be important to consider gender differences when developing prevention and intervention programming for college students.

Results highlight the role of traumatic intrusions in predicting alcohol problems, which is consistent with research suggesting that alcohol may serve to self-medicate distress among trauma-exposed individuals (37). Findings also converge with research suggesting that individuals with a history of child abuse and alcohol problems may have a greater likelihood of engaging in SRB (12). Drinking to the point of experiencing alcohol problems may increase SRB by diminishing sexual inhibitions (13) or increasing problems with sexual assertiveness (16). Per alcohol myopia theory, results suggest that college students with problematic alcohol use may be more likely to focus on the short-term benefits of sexual behavior and overlook the potential for negative consequences (for review see 38).

Findings from the current study should be considered in the context of limitations. Although the hypothesized model was supported in the present study and alternate models were a worse fit, data were cross-sectional which precludes definitive statements about the temporal ordering of the study variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to draw more definitive conclusions regarding temporal relations among these variables. Additionally, trauma symptoms were assessed in the form of traumatic intrusions, rather than assessing posttraumatic symptoms more generally or those stemming specifically from sexual or physical abuse. Although the approach used in the current study captures an aspect of psychopathology that is unique to posttraumatic sequelae, alcohol problems could also develop in relation to other trauma symptoms (e.g., sleep problems, hyperarousal); thus, it would be interesting to investigate the role of trauma symptoms more generally in future studies. The use of an undergraduate sample may also limit the generalizability of our findings as participants may not be representative of all emerging adults. Future studies should extend these findings to more diverse populations, including those with less education, clinical levels of symptomatology, and a greater proportion of men. Nonetheless, the racially diverse sample represents a significant strength of the current study. Finally, models only accounted for 2–13% of the variance in different SRBs, which underscores the notion that SRB is influenced by factors at multiple levels ranging from individual to societal. However, understanding even a small proportion of the variance in high-risk sexual behavior has public health relevance and can guide the development of more effective prevention efforts. Although we focused on individual-level factors, it will be important for future studies to consider interactions between individual-level and contextual variables to account for a greater proportion of the variance in SRB (39).

Despite these limitations, findings have potentially important implications. Some work indicates that alcohol and SRB-focused interventions are minimally effective in reducing SRB (19), and programming implemented on college campuses to address alcohol consumption and binge drinking often fails to discuss the risk for SRB that can occur in the context of alcohol use (40). Thus, there may be value in evaluating the effectiveness of integrated interventions targeting alcohol problems, SRB, and traumatic intrusions concomitantly, when appropriate, rather than treating these behaviors/symptoms as unrelated entities. Furthermore, the gender differences observed here suggest that gender may be a key variable on which to tailor risk reduction programs for drinking problems or SRB.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation was partially supported by T32DA031099 (Walsh).

Footnotes

Note: The findings and conclusions of this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Topics, indicators, and objectives. 2011 Retrieved January, 30 2013, from www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Leading-Health-Indicators-for-Healthy-People-2020/Table.aspx.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messman-Moore TL, Walsh K, DiLillo D. Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:967–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Srednicki O. Childhood sexual abuse, dissociation, and adult self-destructive behavior. J Child Sex Abuse. 2001;10:75–90. doi: 10.1300/j070v10n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senn TE, Carey MP. Child maltreatment and women’s adult sexual risk behavior: Child sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:324–335. doi: 10.1177/1077559510381112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:e11. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, et al. Child sexual abuse and alcohol use among women: Setting the stage for risky sexual behavior. In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O’Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanjuan PM, Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E. The role of sexual assault and sexual dysfunction in alcohol/other drug use disorder. Alcohol Treat Quarterly. 2009;27:150–163. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supp 14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbey A, Saenz C, Buck PO. The cumulative effects of acute alcohol consumption, individual differences and situational perceptions on sexual decision making. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:82–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, et al. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oshri A, Tubman JG, Burnette ML. Childhood maltreatment histories, alcohol and other drug use symptoms, and sexual risk behavior in a treatment sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:250–257. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchowski LM, Barnett NP. Alcohol-related sexual consequences during the transition from high school to college. Addict Behav. 2012;37:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dermen KH, Thomas SN. Randomized controlled trial of brief interventions to reduce college students’ drinking and risky sex. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:583. doi: 10.1037/a0025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaaf KK, McCanne TR. Relationship of childhood sexual, physical, and combined sexual and physical abuse to adult victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:1119–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein JN, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, et al. PTSD as a mediator between childhood rape and alcohol use in adult women. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Vincour D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and HIV risk among poor, inner-city women receiving care in an emergency department. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:120–126. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King KM, Nguyen HV, Kosterman R, et al. Co-occurrence of sexual risk behaviors and substance use across emerging adulthood: evidence for state-and trait-level associations. Addiction. 2012;107:1288–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report questionnaire and manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, et al. Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Psych Assessment. 2007;19:253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson D, O’Hara MW, Chmielewski M, et al. Further validation of the IDAS: Evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psych Assessment. 2008;20:248–259. doi: 10.1037/a0012570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turchik JA, Garske JP. Measurement of sexual risk taking among college students. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:936–948. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9388-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychol Bull. 1998;124:22. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiLillo D, Fortier MA, Hayes SA, et al. Retrospective Assessment of Childhood Sexual and Physical Abuse A Comparison of Scaled and Behaviorally Specific Approaches. Assessment. 2006;13:297–312. doi: 10.1177/1073191106288391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clin Child Family Psychol Rev. 1999;2:55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, et al. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Direct Psychol Science. 2004;13:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin JA, Umstattd MR, Usdan SL. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among collegiate women: A review of research on Alcohol Myopia Theory. J Am Coll Health. 2010;58:523–532. doi: 10.1080/07448481003621718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper ML. Toward a person x situation model of sexual risk-taking behaviors: Illuminating the conditional effects of traits across sexual situations and relationship contexts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:319–341. doi: 10.1037/a0017785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaly PW, Heesacker M, Frost HM. Collegiate alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior: A literature review. J College Stud Dev. 2002;43:838–850. [Google Scholar]