Abstract

Purpose

Age at sexual initiation is strongly associated with sexually transmitted infections (STI), yet prevention programs aiming to delay sexual initiation have shown mixed results in reducing STI. This study tested three explanatory mechanisms for the relationship between early sexual debut and STI: number of sexual partners, individual characteristics, and environmental antecedents.

Methods

A test-and-replicate strategy was employed using two longitudinal studies: the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and Raising Healthy Children (RHC). Childhood measures included pubertal age, behavioral disinhibition, family, school, and peer influences. Alcohol use and age of sexual debut were measured during adolescence. Lifetime number of sexual partners and having sex under the influence were measured during young adulthood. STI diagnosis was self-reported at age 24. Early sex was defined as debut at <15 years. Path models were developed in SSDP evaluating relationships between measures and were then tested in RHC.

Results

The relationship between early sex and STI was fully mediated by lifetime sex partners in SSDP, but only partially in RHC, after accounting for co-occurring factors. Behavioral disinhibition predicted early sex, early alcohol use, number of sexual partners, and sex under the influence, but had no direct effect on STI. Family management protected against early sex and early alcohol use, while antisocial peers exacerbated the risk.

Conclusions

Early sexual initiation, a key mediator of STI, is driven by antecedents that influence multiple risk behaviors. Targeting co-occurring individual and environmental factors may be more effective than discouraging early sexual debut and concomitantly improve other risk behaviors.

Keywords: Early sexual initiation, Sexually transmitted infection, Lifetime number of sexual partners, Sex under the influence, Family management, Antisocial peers, Alcohol use, Behavioral disinhibition, Adolescence

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) are among the most commonly occurring infections in the United States. Approximately 20 million new cases occur every year, nearly half of which are among young adults aged 18–24 [1]. Despite prevention efforts, there has been little reduction in rates of Chlamydia trachomatis and other common STI [2], suggesting current prevention approaches are not sufficiently effective.

Early sexual initiation is one of the most robust predictors of STI among adolescents and young adults [3–6], making this an attractive target for prevention efforts. Prevention programs promoting abstinence or delay of sexual activity among adolescents, however, have had mixed results in reducing STI [7, 8]. Other prevention approaches, focused on decision making, proper condom use, and negotiation skills, have been shown to reduce sexual risk behavior [9], but have short-lived and moderate effects [10]. Given the strong links between early sexual debut and later STI, more robust and sustainable intervention targets may be identified by examining mechanisms for this relationship.

Three potential mechanisms for this link have shown promise. The first focuses exclusively on sexual behaviors and assumes a single causal pathway, from pubertal age, to early sexual initiation, and subsequently number of lifetime sexual partners by young adulthood, assuming the effect of early sex is mediated by the number of sexual partners. Ample literature links pubertal timing, early sex, and number of sexual partners [4, 11–15]. Studies have further linked number of sexual partners and STI [13, 16, 17]. James [14] used path modeling to show the causal chain between pubertal timing, age of initiation, and sexual risk behavior, but did not evaluate the effect on STI itself.

The second mechanism examines a role of behavioral disinhibition and alcohol use in exacerbating STI risk [17–19]. Adolescents who initiate intercourse early are more likely to use alcohol and to report alcohol problems compared to their peers who delay sex [e.g., 20]; conversely, adolescent alcohol use is associated with STI [for review, see 21]. A tendency toward behavioral disinhibition, indicated by impulsivity and sensation seeking, has commonly been theorized to explain the comorbidity in problem behaviors, such as the link between alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and STI [22]. This suggests a pathway from behavioral disinhibition, to early sex and early alcohol use, followed by having sex under the influence, and subsequently, STI.

The third explanatory mechanism hypothesizes that early environmental antecedents common to early alcohol use and early sexual debut explain increased risk for STI [23]. In the family domain, monitoring of child activities is an especially important factor in adolescent sexual risk taking and STI [24–28]. Peer delinquency and school bonding have also been found to predict risky sexual behavior and STI acquisition [26, 29–31]. Since these same environmental factors have been linked to substance-related risk behaviors [32], they may account for the apparent relationship between early alcohol use and early sex and also between early sex and STI.

Current study

The current study employed an innovative test-and-replicate strategy using two longitudinal datasets to test these hypothesized explanations of the early sexual debut–STI link. First, the three discrete mechanisms were tested in the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) longitudinal dataset. The first hypothesis posited that it is the cumulative exposure to multiple sexual partners, permitted by earlier sexual initiation, that predicts STI risk. Thus, early sexual debut was hypothesized to be a marker for number of lifetime sexual partners, increasing risk for STI. Hypotheses 2 and 3 postulated that early sex and early alcohol use have common antecedents that explain their co-occurrence in adolescence. The same antecedents predict risky sexual practices (e.g., having sex under the influence) in young adulthood, and subsequent STI. Hypothesis 2 tested the effect of childhood behavioral disinhibition as a common individual-level antecedent, whereas Hypothesis 3 examined the effects of environmental antecedents in the family, peer, and school domains. Because Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are not mutually exclusive, a final step combined them into a single omnibus model using the SSDP dataset and tested the model’s stability through replication in another longitudinal sample, the Raising Healthy Children (RHC) study.

Methods

Participants

The Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and Raising Healthy Children (RHC) are two longitudinal studies of youth development. In 1985, the SSDP recruited 808 fifth graders (mean age 10.70, SD = 0.52) from 18 Seattle public schools, many of which served low-income households. Participant surveys used in this study were conducted annually from ages 10 to 16, with follow-up at ages 18, 21, and 24 (collected in 1999). Interviews with parents were conducted annually when youth were aged 10 to 16. Data collection continues, and retention rates for the sample have remained high (>90%) since the age 14 interview in 1989.

The 1040 participants of RHC were drawn from a suburban school district near Seattle. Participants were enrolled in first (younger cohort) or second grade (older cohort) in 1993 and 1994, and were then followed annually in the spring until 2011, when the younger cohort was age 24, and the older cohort was 25 years old. Additional interviews were conducted in the fall of 2004, 2005, and 2006 during the two years post high school. Parent interviews were conducted annually through age 18. Retention rates for the RHC sample have also remained high (85% and higher) since study inception. Both studies were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Measures

Lifetime sexually transmitted infection (STI)

Participants reported whether they were ever told by a doctor or nurse that they had an STI. In SSDP, the questionnaire included two items regarding diagnosis of HIV/AIDS and “sexually transmitted disease (STD or VD, other than HIV/AIDS), such as gonorrhea, genital warts, chlamydia, trich, herpes, or syphilis” (age 21, 24). The RHC questionnaire included a question about HIV/AIDS and 12 additional items naming specific STI (ages 19–24). Only five participants reported HIV/AIDS diagnosis, so this was combined with other STI. Diagnosis was coded as 1 if a participant responded “yes” in any interviews and 0 if they responded “no” in all interviews (or had no sexual partners). STI diagnosis was modeled as a binary (categorical) variable in the analyses.

Young adult predictors (ages 18–24)

Number of sexual partners. Lifetime number of sexual partners was assessed at age 24 in SSDP and 22–24 in RHC (highest number across the assessments, capped at 20) and modeled as normally distributed. Sex under the influence assessed how often participants engaged in sexual intercourse after drinking alcohol or using drugs (1 “never” to 5 “every time.”) Drinking alcohol before having sex more than half of the time and/or ever using illicit drugs before having sex was coded as 1 (otherwise coded as 0). The number of assessments from age 18 to 24 during which participants reported having sex under the influence (i.e., chronicity) was used as a risk score and modeled as a categorical variable.

Adolescent predictors

Early sexual initiation. Past-year sexual behavior was self-reported and collected prospectively. Additionally, in SSDP, age at first sexual initiation was self-reported retrospectively at ages 18 and 24. Sexual initiation was coded as 1 (early) if participants reported age of debut earlier than 15, a definition used in previous studies [11], and 0 if sex was initiated at age 15 or later. Initiation of sexual activity prior to age 10 was coded as missing due to concerns about nonconsensual sexual activity. The variable was modeled as binary. Early alcohol use reflected the chronicity (number of years) of alcohol use between ages 10 and 14 in SSDP and 10 and 15 in RHC and modeled as a categorical risk index.

Childhood predictors (ages 10–14)

A behavioral disinhibition (BD) measure (five items per wave in SSDP, three in RHC) assessed impulse-control problems and was modeled as a continuous variable. Examples include “How often do you do what feels good, regardless of the consequences?” and “How often do you do something dangerous because someone dared you to do it?” Items were scored on a 5-point scale (1 “never” to 6 “once a week or more”) and summed for a single risk score. Family management was assessed in the parent interview and included items on parental monitoring, rules, discipline, and rewards (six in SSDP, five in RHC). Items were summed and modeled as continuous. Response options were 1 “NO!” 2 “no” 3 “yes” 4 “YES!” where greater values correspond to more monitoring of child activities. School bonding (eight in SSDP, five in RHC) reflected liking school, classes, teachers, and school assignments, and was modeled as a continuous variable. Response options ranged from 1 “NO!” to 4 “YES!” with higher values reflecting greater school bonding. Participants’ self-report of Antisocial peers included five items per wave measuring friends being in trouble with teachers, police, school suspension/expulsion, or gang activities (close friends and other peers). Response options included “yes/no”, count of antisocial peers, and 4-point scale (1 “NO!” to 4 “YES!”). Because of the differently scaled items, variables were standardized at each age prior to averaging; higher values represented more antisocial peers. Age of pubertal onset was self-reported retrospectively (ages 18, 24 in SSDP; 17–18 in RHC).

Demographics

Gender and ethnicity were self-reported. Ethnicity in SSDP was categorized as Black, Asian, and Native American (reference: White). In RHC, the racial/ethnic categories are White (vs. Non-White) because individual minority groups were too small to permit generalization. Eligibility for the National School Lunch/Breakfast program from school records was used as a proxy for childhood socioeconomic status. Parent age at birth of target child determined if participants were born to teenage parents.

Statistical Analyses

We first evaluated the relationship between STI and the potential predictors using probit regression to generate “baseline” beta coefficients (adjusted for demographics). We then tested three models of specific mechanisms by which early sexual initiation and STI diagnosis may be linked using path modeling [33]. Path modeling, which is a type of structural equation modeling (SEM), is a powerful methodology that examines how multiple predictors are related to STI as well as to each other by estimating multiple simultaneous regressions between variables in the model. We chose this methodology over traditional regression analysis in order to explicitly test mediators, such as number of sexual partners, which may explain the relationships between early sex and STI. Path model coefficients are interpreted as standardized regression betas ranging from −1 to 1 and represent change in units of an outcome per one standard deviation change in the predictor. We also calculated the change in beta (Δβ), defined as the “baseline” beta for a predictor minus the beta for that same predictor in a given path model, to determine how much of the effect was accounted for by the other variables in the model.

Models were estimated using Mplus 7 [34]. Hypotheses 1 through 3 were tested in the SSDP dataset; the omnibus model was first estimated in SSDP and then estimated and assessed for potential replication in RHC. Appendix 1 contains unstandardized and standardized coefficients and standard errors for the omnibus models. Bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Appendix 2. Each model was saturated, meaning that direct paths were estimated between each predictor and each outcome variable. Because both studies included an intervention in early childhood [for study designs see 35, 36], intervention status was included as a covariate in all analyses. All models were adjusted for demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, being a child of a teenage parent, childhood SES) and cohort membership (in RHC) to control for differences in mean levels of the variables, such as gender differences in STI prevalence. Checks of model comparability showed no differences in structural paths by treatment condition, gender, or ethnicity, meaning that associations between variables did not vary by these groups and analyses stratified by these groups were not necessary.

Appendix 1.

Unstandardized and standardized parameters for Model 4: SSDP and RHC samples

| SSDP sample | RHC sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Parameter | Unstand. Estimate | SE | Standardized Estimate | Unstand. Estimate | SE | Standardized Estimate |

| Structural paths | ||||||

| Pubertal age → Early sex | −.21 | .04 | −.26*** | −.16 | .04 | −.18*** |

| Behavioral disinhibition → Early sex | .33 | .10 | .21** | .33 | .05 | .32*** |

| Family management → Early sex | −.41 | .19 | −.11* | −.14 | .14 | −.05 |

| School bonding → Early sex | .11 | .16 | .04 | −.08 | .16 | −.02 |

| Antisocial peers → Early sex | .52 | .16 | .18*** | .62 | .11 | .29*** |

| Child of teen parent → Early sex | .15 | .15 | .04 | .30 | .18 | .07+ |

| Male → Early sex | .68 | .14 | .25*** | −.48 | .12 | −.19*** |

| White → Early sex | - | - | - | −.04 | .12 | −.01 |

| Black → Early sex | .27 | .44 | .09 | - | - | - |

| Asian → Early sex | −.56 | .55 | −.17*** | - | - | - |

| Native → Early sex | .48 | .78 | .08 | - | - | - |

| Free lunch → Early sex | .19 | .19 | .07 | .36 | .11 | .14** |

| Older cohort → Early sex | - | - | - | −.36 | .11 | −.14** |

| Treatment → Early sex | −.45 | .18 | −.16** | −.02 | .11 | −.01 |

| Pubertal age → Early alcohol use | −.03 | .03 | −.05 | −.03 | .02 | −.04 |

| Behavioral disinhibition → Early alcohol use | .16 | .05 | .12** | .20 | .04 | .20*** |

| Family management → Early alcohol use | −.33 | .16 | −.10* | −.50 | .10 | −.17*** |

| School bonding → Early alcohol use | −.30 | .14 | −.13* | −.34 | .12 | −.10** |

| Antisocial peers → Early alcohol use | .31 | .13 | .12* | .56 | .08 | .27*** |

| Child of teen parent → Early alcohol use | −.13 | .13 | −.04 | −.25 | .13 | −.06* |

| Male → Early alcohol use | −.10 | .10 | −.04 | −.16 | .08 | −.07* |

| White → Early alcohol use | - | - | - | −.05 | .09 | −.02 |

| Black → Early alcohol use | −.44 | .75 | −.17 | - | - | - |

| Asian → Early alcohol use | −.75 | .85 | −.27 | - | - | - |

| Native → Early alcohol use | −.26 | 3.26 | −.05 | - | - | - |

| Free lunch → Early alcohol use | −.28 | .35 | −.12 | .19 | .08 | .08* |

| Older cohort → Early alcohol use | - | - | - | −.20 | .07 | −.08** |

| Treatment → Early alcohol use | .04 | .15 | .02 | .04 | .08 | .02 |

| Early sex → Lifetime sex partners | 1.65 | .34 | .34*** | 1.62 | .33 | .31*** |

| Early alcohol use → Lifetime sex partners | .65 | .29 | .11* | .41 | .25 | .08+ |

| Pubertal age → Lifetime sex partners | −.04 | .17 | −.01 | −.10 | .15 | −.02 |

| Beh. disinhibition → Lifetime sex partners | .76 | .33 | .10* | .61 | .22 | .11** |

| Family management → Lifetime sex partners | −.16 | .77 | .01 | .28 | .56 | .02 |

| School bonding → Lifetime sex partners | −.34 | .57 | −.03 | .29 | .64 | .02 |

| Antisocial peers → Lifetime sex partners | .62 | .66 | .04 | .67 | .46 | .06 |

| Child of teen parent → Lifetime sex partners | .69 | .63 | .04 | 1.69 | .74 | .07* |

| Male → Lifetime sex partners | 1.47 | .55 | .11** | .12 | .46 | .01 |

| White → Lifetime sex partners | - | - | - | −.46 | .45 | −.03 |

| Black → Lifetime sex partners | −.52 | 1.18 | −.04 | - | - | - |

| Asian → Lifetime sex partners | −.77 | 1.36 | −.05 | - | - | - |

| Native → Lifetime sex partners | −.42 | 3.78 | −.01 | - | - | - |

| Free lunch → Lifetime sex partners | −.43 | .66 | −.03 | .31 | .42 | .02 |

| Older cohort → Lifetime sex partners | - | - | - | −.99 | .44 | −.08* |

| Treatment → Lifetime sex partners | .59 | .82 | .04 | .03 | .41 | .00 |

| Early sex → Sex under the influence | .21 | .09 | .24** | .05 | .07 | .06 |

| Early alcohol use → Sex under the influence | .01 | .08 | .01 | .19 | .05 | .20*** |

| Pubertal age → Sex under the influence | .00 | .04 | .00 | −.02 | .03 | −.03 |

| Beh. disinhibition → Sex under the influence | .18 | .07 | .13** | .18 | .04 | .20*** |

| Family mgmt. → Sex under the influence | −.19 | .15 | −.05 | .08 | .10 | .03 |

| School bonding → Sex under the influence | .10 | .13 | .04 | −.06 | .13 | −.02 |

| Antisocial peers → Sex under the influence | .30 | .14 | .12* | .21 | .09 | .11* |

| Child of teen parent → Sex under the infl. | −.04 | .14 | −.01 | .19 | .14 | .05 |

| Male → Sex under the influence | .39 | .13 | .16** | −.14 | .09 | −.06 |

| White → Sex under the influence | - | - | - | .08 | .09 | .03 |

| Black → Sex under the influence | −.11 | .57 | −.04 | - | - | - |

| Asian → Sex under the influence | −.77 | .64 | −.26 | - | - | - |

| Native → Sex under the influence | −.16 | 2.56 | −.03 | - | - | - |

| Free lunch → Sex under the influence | .00 | .26 | .00 | −.11 | .08 | −.05 |

| Older cohort → Sex under the influence | - | - | - | −.25 | .08 | −.11** |

| Treatment → Sex under the influence | .08 | .18 | .03 | −.11 | .08 | −.05 |

| Lifetime sex partners → STI diagnosis | .05 | .01 | .27*** | .04 | .01 | .21*** |

| Sex under the influence → STI diagnosis | .09 | .08 | .09 | .14 | .06 | .13* |

| Early sex → STI diagnosis | .14 | .09 | .15 | .17 | .09 | .18* |

| Early alcohol use → STI diagnosis | .10 | .07 | .09 | .02 | .06 | .02 |

| Pubertal age → STI diagnosis | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | .00 | .04 | .00 |

| Beh. disinhibition → STI diagnosis | −.15 | .09 | −.10+ | .03 | .06 | .03 |

| Family management → STI diagnosis | −.17 | .19 | −.05 | −.18 | .14 | −.06 |

| School bonding → STI diagnosis | −.19 | .13 | −.08 | .17 | .17 | .05 |

| Antisocial peers → STI diagnosis | .31 | .15 | .12* | −.02 | .12 | −.01 |

| Child of teen parent → STI diagnosis | −.05 | .15 | −.02 | .12 | .17 | .03 |

| Male → STI diagnosis | −.71 | .15 | −.29*** | −.92 | .12 | −.37*** |

| White → STI diagnosis | - | - | - | −.07 | .12 | −.03 |

| Black → STI diagnosis | .41 | .15 | .15** | - | - | - |

| Asian → STI diagnosis | −.01 | .23 | .00 | - | - | - |

| Native → STI diagnosis | −.10 | .89 | −.02 | - | - | - |

| Free lunch → STI diagnosis | .25 | .14 | .10+ | .10 | .11 | .04 |

| Older cohort → STI diagnosis | - | - | - | .21 | .11 | .09* |

| Treatment → STI diagnosis | −.24 | .20 | −.10 | −.11 | .10 | −.04 |

| Correlational paths | ||||||

| Early alcohol use ↔ Early sex | −.01 | .08 | −.01 | .21 | .06 | .21*** |

| Sex under the infl. ↔ Lifetime sex partners | 1.56 | .29 | .27*** | 2.53 | .24 | .44*** |

p < .10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Appendix 2.

Model variable intercorrelations

| Lifetime STI diagnosis | Lifetime partners | Sex under influence | Early alcohol use | Early sex | Family Mgmt. | School bonding | Antisocial peers | Pubertal age | BD | Male | Teen parent | White | Black | Asian | Native | Free lunch | Older cohort | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lifetime STI diagnosis | - | .36*** | .26*** | .17** | .35*** | −.16** | −.19** | .30*** | −.16** | .14* | −.15*** | .12* | n/a | .27*** | −.22*** | .00 | .14** | n/a | −.19* |

| 2. Lifetime partners | .36*** | - | .47*** | .21*** | .45*** | −.13*** | −.18*** | .28*** | −.14*** | .33*** | .23*** | .10** | n/a | .07+ | −.21*** | .03 | −.05 | n/a | −.05 |

| 3. Sex under influence | .29*** | .60*** | - | .18*** | .45*** | −.15** | −.16*** | .34*** | −.11* | .36*** | .26*** | .08+ | n/a | .13** | −.35*** | .04 | −.04 | n/a | −.05 |

| 4. Early alcohol use | .16*** | .25*** | .30*** | - | .15** | −.15*** | −.26*** | .21*** | −.09** | .26*** | .01 | −.04 | n/a | −.07+ | −.28*** | .01 | −.19*** | n/a | −.02 |

| 5. Early sex | .35*** | .44*** | .29*** | .38*** | - | −.22*** | −.20*** | .44*** | −.31*** | .42*** | .28*** | .19*** | n/a | .24*** | −.30*** | .09+ | .08+ | n/a | −.22** |

| 6. Family mgmt. | −.11* | −.13*** | −.15*** | −.35*** | −.24*** | - | .34*** | −.28*** | −.01 | −.20*** | −.11*** | −.02 | n/a | .04 | −.08* | .00 | −.08* | n/a | .14** |

| 7. School bonding | −.01 | −.11*** | −.17*** | −.30*** | −.20*** | .43*** | - | −.24*** | .09* | −.23*** | −.13*** | −.02 | n/a | −.01 | .21*** | .01 | .08* | n/a | .20*** |

| 8. Antisocial peers | .09* | .28*** | .31*** | .44*** | .44*** | −.41*** | −.40*** | - | −.08* | .46*** | .17*** | .16*** | n/a | .26*** | −.19*** | .00 | .09* | n/a | −.10* |

| 9. Pubertal age | −.11* | −.14*** | −.10* | −.09** | −.26*** | .03 | .03 | −.11*** | - | −.15*** | .12** | −.11** | n/a | −.07* | .14*** | −.01 | −.01 | n/a | .01 |

| 10. BD | .13** | .32*** | .32*** | .35*** | .46*** | −.24*** | −.26*** | .49*** | −.11*** | - | .15*** | .05 | n/a | .04 | −.22*** | .05 | −.06 | n/a | .00 |

| 11. Male | −.37*** | .03 | .02 | .08* | −.05 | −.06+ | −.13*** | .27*** | .04 | .26*** | - | .02 | n/a | .00 | .04 | −.07+ | −.05 | n/a | −.03 |

| 12. Teen parent | .09* | .11*** | .06 | −.04 | .11* | .06+ | .02 | .02 | −.04 | .03 | −.04 | - | n/a | .22*** | −.11** | −.03 | .13*** | n/a | −.16** |

| 13. White | −.05 | −.05 | .03 | −.03 | −.04 | .03 | −.06+ | −.04 | .06+ | .05+ | .03 | −.01 | - | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 14. Black | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | - | −.31*** | −.14 | .27*** | n/a | −.10* |

| 15. Asian | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | - | −.13 | .16*** | n/a | .07 |

| 16. Native | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | - | .06 | n/a | .07 |

| 17. Free lunch | .11* | .12*** | .01 | .08* | .19*** | .01 | .09** | .09** | −.04 | .01 | .00 | .11*** | −.19*** | n/a | n/a | n/a | - | n/a | −.01 |

| 18. Older cohort | .01 | −.11** | −.10** | −.07* | −.12** | .03 | .02 | .02 | .02 | .07* | .04 | −.08* | .01 | n/a | n/a | n/a | −.08* | - | n/a |

| 19. Treatment | −.08+ | −.01 | −.04 | .03 | −.03 | −.05 | −.07* | .01 | .02 | −.02 | .04 | −.03 | .00 | n/a | n/a | n/a | −.10** | −.04 | - |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Correlations for the SSDP dataset are presented above the diagonal. Correlations for RHC are below the diagonal

Results

Both study samples were gender-balanced, but participants in SSDP were racially and ethnically more diverse (47% Caucasian versus 75% in RHC; Table 1). Over half of participants (52%) in SSDP received free or reduced-price lunch in fifth to seventh grade, whereas this was true for 38% of RHC participants. Approximately one third (36.7%) of SSDP participants, but only 17.9% of RHC youth reported early sexual initiation (before age 15), but by ages 24/25, a fifth of each sample had self-reported an STI. In SSDP, the STI rate was 32.5% for early initiators of sex compared to 16.6% later initiators (Pearson’s χ2 p<.001); rates in RHC were comparable (34.4% vs. 15.8%; p<.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study samples

| Self-report measure | SSDP N = 808 n (%) reporting > 0 behaviors or mean (SD) |

RHC N = 1040 n (%) reporting > 0 behaviors or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Women | 39 (49.0%) | 492 (47.3%) |

| White | 381 (47.2%) | 783 (75.3%) |

| African American | 207 (25.6%) | 36 (3.5%) |

| Native American | 43 (5.3%) | 24 (2.3%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 177 (21.9%) | 70 (6.7%) |

| Mixed | - | 127 (12.2%) |

| Treatment condition | 156 (19.3%) | 562 (54.0%) |

| Received free lunch | 423 (52.4%) | 395 (38.0%) |

| Child of a teen parent | 127 (15.7%) | 96 (9.2%) |

| Model variables | ||

| Sexually transmitted infection | 176 (21.8%) | 199 (19.1%) |

| Sex under the influence | 446 (32.9%) | 442 (42.5%) |

| Early sexual initiation | 295 (36.5%) | 186 (17.9%) |

| Early alcohol use† | 2.04 (1.68) | 1.31 (1.41%) |

| No. of lifetime sexual partners†* | 7.93 (6.61) | 7.94 (6.58) |

| Pubertal age† | 12.48 (1.63) | 12.76 (1.45) |

| Behavioral disinhibition† | 1.81 (.86) | 2.90 (1.21) |

| Family management† | 3.50 (.38) | 3.31 (.42) |

| School bonding† | 2.93 (.50) | 3.24 (.36) |

| Antisocial peers† | .01 (.45) | .00 (.59) |

Note.

Number of lifetime sexual partners capped at 20. At age 24, 94% of all participants in SSDP and RHC reported at least one sexual partner.

mean (SD).

In probit regression analyses, early sexual debut was associated with increased risk of STI, with “baseline” betas of .33 in SSDP and .37 in RHC (Table 2). In both samples, lifetime number of sex partners, behavioral disinhibition, early alcohol use, sex under the influence, and antisocial peers were also associated with increased risk of STI. Older pubertal age and higher levels of family management and school bonding were associated with decreased risk.

Table 2.

Baseline beta coefficients reflecting association of individual predictors of STI, adjusted for demographics a

| SSDP βb |

RHC βb |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pubertal age | −.10* | −.08+ |

| Early sex | .33*** | .37*** |

| Lifetime number of sexual partners | .39*** | .36*** |

| Behavioral disinhibition | .14** | .23*** |

| Early alcohol use | .20** | .20*** |

| Sex under influence | .27*** | .30*** |

| Family management | −.17*** | −.14** |

| School bonding | −.17** | −.07 |

| Antisocial peers | .25*** | .20*** |

Analyses adjusted for gender, ethnicity, SES, treatment condition, being the child of a teen parent, and cohort (RHC only)

Unexponentiated standardized beta coefficients from probit regression analyses

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

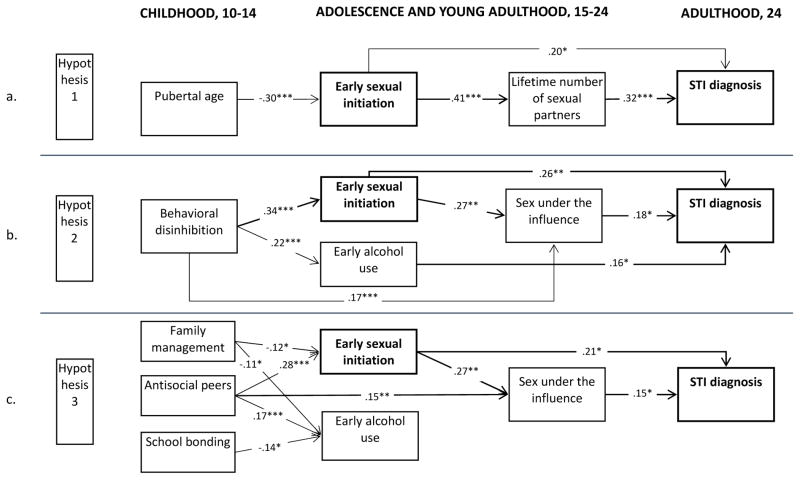

The model testing Hypothesis 1 using SSDP data is shown in Figure 1a. Results indicated that, consistent with expectations, earlier puberty predicted earlier sexual debut (β= −.30), which in turn predicted a higher number of partners (β=.41). The effect of early sexual debut on STI diagnosis (β=.20) remained, but was substantially attenuated from the “baseline” relationship in Table 2 (Δβ=.13) by number of sexual partners, suggesting partial but not complete mediation.

Figure 1. Models testing Hypotheses 1–3 in SSDP dataset.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Coefficients in the models are partial standardized betas. All models are saturated, such that all dependent variables are regressed onto all model predictors. Where lines are not drawn, the relationships are nonsignificant at p < .05 level. All variables controlled for gender, childhood SES, ethnicity, and being the child of a teen parent. In Figure 1c, correlations between Family management (A), Antisocial peers (B), and School bonding (C) are as follows: AB = −.29***, BC = −.22***, AC = .36***.

The second hypothesis examined whether behavioral disinhibition drives risky behaviors like early sex, early alcohol use, and sex under the influence, which then results in STI acquisition (Figure 1b). Although we expected overlap between early sex and early alcohol use (bivariate correlation r=.15, p<.01; Appendix 2), after including behavioral disinhibition in the model, the two were no longer significantly related. Behavioral disinhibition predicted greater likelihood of both early sexual debut (β=.34) and early alcohol use (β=.22), and was directly related to having more sex while under the influence (β=.17). However, behavioral disinhibition did not predict STI directly, nor did it completely explain the relationship between early sex or early alcohol use and STI, as demonstrated by the continued presence of direct links between these factors (βearly sex=.26; βalcohol use=.16) and STI. Early sex predicted more sex under the influence (β=.27). Both early sex and early alcohol use were related to greater likelihood of STI, although the effect of both was somewhat attenuated from “baseline” effects (Δβ=.07, .04, respectively). Thus, results were somewhat consistent with Hypothesis 2 in showing that behavioral disinhibition increased risk-taking behavior; however, behavioral disinhibition did not appear to explain much of the link between early sexual initiation and STI.

The model for Hypothesis 3 (Figure 1c) showed that environmental antecedents played a role in increasing the likelihood of early sex and early alcohol use, but did not directly predict STI. Having antisocial peers had the strongest effect on increased risk of early sex (β=.28) and alcohol use (β=.17). Family management appeared to buffer engagement in early sex (β= Δ.12) and early alcohol (β= Δ.11), and school bonding protected against early alcohol use (β= Δ.14). Partially consistent with Hypothesis 3, having antisocial peers was linked with greater likelihood of having sex under the influence (β=.15). Notably, after accounting for environmental antecedents, early alcohol use no longer predicted STI. The relationship between early sexual debut and STI remained (β=.21), although it was moderately attenuated from the “baseline” relationship (Δβ=.12).

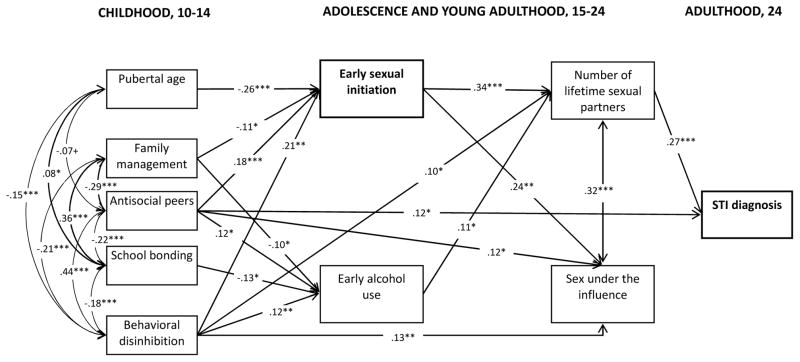

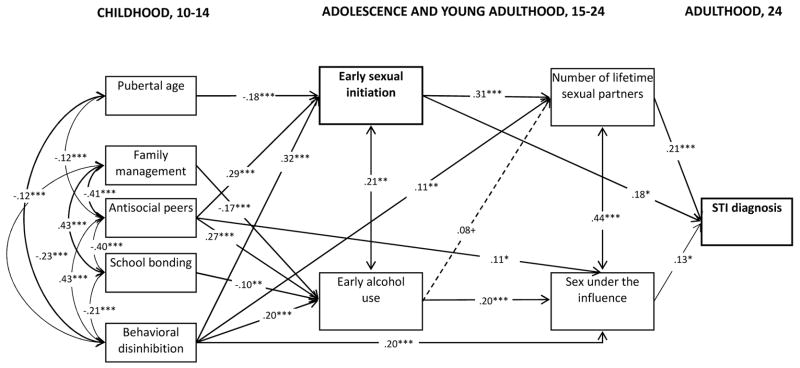

A final model examining the relative contribution of all of the predictors was tested in SSDP and replicated in the RHC dataset (Figures 3–4). Overall, the omnibus models integrated and supported findings from Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. The strongest predictor of STI diagnosis was the number of sexual partners, a finding that was replicated in both SSDP (β=.27) and RHC (β=.21) studies. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the effect of early sex was completely mediated through number of sexual partners in SSDP, whereas in RHC, a significant, although attenuated effect remained (β=.18; Δβ=.19). The effect of behavioral disinhibition on increased risky behavior in adolescence and in young adulthood tested by Hypothesis 2 was replicated in both models. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the effect of behavioral disinhibition on STI was indirect through early sexual initiation, sex under the influence, and number of lifetime partners. The alcohol-specific pathway from early alcohol use, to sex under the influence, to STI was evident only in RHC. Finally, Hypothesis 3 regarding early environmental predictors’ effects on adolescent risk was replicated in both samples. Additionally, in SSDP, the presence of antisocial peers directly predicted STI diagnosis.

Figure 3. Replication model. Childhood and adolescent predictors of STI infection at age 24 in RHC.

Note. + p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Coefficients in the models are partial standardized betas. The model is saturated, such that all dependent variables are regressed onto all model predictors. Paths that are marginally significant at p < .10 are only shown (as dashed lines) when significant in Figure 2. All variables controlled for gender, childhood SES, ethnicity, and being the child of a teen parent.

Discussion

The current study examined three mechanisms that may explain the link between early sexual initiation and STI: number of sexual partners, behavioral disinhibition, and environmental antecedents. In accordance with the first mechanism, accounting for lifetime number of sexual partners completely explained the relationship between early sexual debut and STI in one dataset and significantly attenuated the relationship in the other. In the second mechanism, behavioral disinhibition, although not directly related to STI diagnosis, predicted all the other risk factors for STI, suggesting it is a common driver of risk. Similarly, family, school, and peer environments were linked to risk behaviors, and (in SSDP) antisocial peers had a direct effect on STI diagnoses in addition to the effect on the risk behaviors.

Our observation that behavioral disinhibition appeared to drive sexual and alcohol-related risk behavior is consistent with prior findings showing that childhood behavioral disinhibition is related to adolescent risk behaviors, including those that are and are not sexual in nature [37, 38]. The absence of a direct relationship between behavioral disinhibition and STI diagnosis suggests that individual risk traits operate through intervening behaviors, such as having sex with multiple partners or under the influence of drugs and alcohol. Behavioral disinhibition has been linked to a number of other risk behaviors [e.g., delinquency 22], and interventions that successfully moderate the influence of this trait, if incorporated into STI prevention strategies, could have broad effects on risk behaviors in general, beyond risky sex. For example, some broad universal interventions have been shown to have STI effects, especially among higher risk youths [28].

Results also supported the hypothesis that environmental antecedents in family, peer, and school domains are related to early sex and other risk behaviors leading to STI acquisition. The consistent links between having antisocial peers in childhood and each of the risk behaviors, with paths following through to STI diagnoses in young adulthood in SSDP, is consistent with Henry and colleagues’ [39] observation that adolescent peer attitudes influenced sexual risk behavior in young adulthood. However, the pathways for family and school influences were not as consistently strong and not all links were observed in both studies. These effects may operate indirectly through behavioral disinhibition and antisocial peers. Altogether, findings suggest that factors earlier in life strongly influence STI risk, and interventions at younger ages may have long-term effects in preventing sexual risk behaviors and subsequent STI.

Over and above individual or environmental factors, lifetime number of sex partners remained the strongest and most consistent predictor of STI. However, given the complex influences on this behavior, prevention messages focusing solely on partner reduction are unlikely to be successful. Nevertheless, lifetime number of sex partners may be an excellent measure of the efficacy of interventions designed to mitigate the effect of behavioral disinhibition or antisocial peer influences on risky sexual practices.

The strengths of the current study include the longitudinal design and the ability to test mediators at different developmental stages. Testing the model for replication in another longitudinal study further strengthened the findings. Although the samples differed in ethnic and socioeconomic diversity and were over a decade apart, the uniformity of results speaks to the stability of the findings. Nevertheless, there are also limitations. First, STI diagnosis was self-reported; respondents may have elected not to report diagnoses and youth who were never tested may have had undetected STI. Second, we could not determine with precision the proximity of some risk factors to STI acquisition. While this limits determination of temporal sequence for some risk factors (e.g., sex under the influence; factors measured after sexual debut), the temporal sequence between behavioral disinhibition and environmental influences in childhood is clear. Finally, the influences on sexual risk behavior and STI are numerous and our examination was not comprehensive. Future studies should examine other mediators, such as peer sexual behavior and family attitudes toward sex among others, which are likely to affect sexual behavior and STI acquisition.

In conclusion, our results suggest that programs aimed at delaying sexual initiation through promoting abstinence until marriage may miss important intervention targets that can be addressed through a broader, social-developmental approach to preventive intervention. For example, self-regulation training may decrease early sexual initiation, as may strengthening family management. Indeed, prevention programs that have been most successful at reducing risky sexual practices have taken multi-pronged approaches, focusing on contraception and STD education and also addressed other risk behaviors, such as substance use [40]. The current study shows that the sexual risk behaviors that lead to STI are affected by multiple childhood and adolescent processes. Prevention programs must address the larger social-developmental risk and protective factors in addition to the proximal causes to successfully reduce sexual risk behavior and STI.

Figure 2. Primary omnibus model depicting childhood and adolescent predictors of STI infection at age 24 in SSDP.

Note. + p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Coefficients in the models are partial standardized betas. The model is saturated, such that all dependent variables are regressed onto all model predictors. All variables controlled for gender, childhood SES, ethnicity, and being the child of a teen parent.

Implications and Contribution.

Early sexual initiation has been linked with sexual risk behavior and sexually transmitted infection (STI). In these analyses, behavioral disinhibition, family management, and antisocial peers influenced the relationship between early sex and STI. Addressing multiple early risk factors, rather than early sexual initiation, may more effectively reduce rates of STI.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; R01DA009679; R01DA024411; R01DA08093) and by grant 21548 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge SSDP and RHC panel participants for their continued contribution to the longitudinal studies. We also acknowledge the SDRG Survey Research Division for their hard work maintaining high panel retention, and the SDRG editorial and administrative staff for their editorial and project support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lisa E. Manhart, Email: lmanhart@uw.edu.

Karl G. Hill, Email: khill@uw.edu.

Jennifer A. Bailey, Email: jabailey@uw.edu.

J. David Hawkins, Email: jdh@uw.edu.

Kevin P. Haggerty, Email: haggerty@uw.edu.

Richard F. Catalano, Email: rico@uw.edu.

References

- 1.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:187–93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2010. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upchurch DM, Mason WM, Kusunoki Y, Kriechbaum MJ. Social and behavioral determinants of self-reported STD among adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:276–87. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.276.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Fam Plan Perspect. 1998;30:271–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg J, Magder L, Aral S. Age at first coitus. a marker for risky sexual behavior in women. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:331–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller HG, Cain VS, Rogers SM, Gribble JN, Turner CF. Correlates of sexually transmitted bacterial infections among U.S. women in 1995. Fam Plan Perspect. 1999;31:4–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santelli J, Ott MA, Lyon M, et al. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of U.S. policies and programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Willan A, Griffith L. Interventions to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2002;324:1426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby D. Emerging Answers. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; Washington, D.C: 2007. [Accessed May 21, 2012]. Available at: http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/EA2007/EA2007_full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30 (Suppl 1):S94–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Dev Rev. 2008;28:153–224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deardorff J, Gonzales NA, Christopher FS, Roosa MW, Millsap RE. Early puberty and adolescent pregnancy: the influence of alcohol use. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1451–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucke JC, Herbert DL, Watson M, Loxton D. Predictors of sexually transmitted infection in Australian women: evidence from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:237–46. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James J, Ellis BJ, Schlomer GL, Garber J. Sex-specific pathways to early puberty, sexual debut, and sexual risk taking: tests of an integrated evolutionary-developmental model. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:687–702. doi: 10.1037/a0026427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sneed CD. Sexual risk behavior among early initiators of sexual intercourse. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1395–400. doi: 10.1080/09540120902893241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leichliter JS, Williams SP, Bland SD. Sexually active adults in the United States: predictors of sexually transmitted diseases and utilization of public STD clinics. J Psychol Human Sex. 2004;16:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buffardi AL, Thomas KK, Holmes KK, Manhart LE. Moving upstream: ecosocial and psychosocial correlates of sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States. AJPH. 2008;98:1128–36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnie R, O’Connell M, editors. Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking, Board on Children, Youth, and Families. National Research Council; 2004. Reducing underage drinking: a collective responsibility. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stueve A, O’Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. AJPH. 2005;95:887–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tubman JG, Windle M, Windle RC. The onset and cross-temporal patterning of sexual intercourse in middle adolescence: prospective relations with behavioral and emotional problems. Child Dev. 1996;67:327–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey JA. Editorial: Addressing common risk and protective factors can prevent a wide range of adolescent risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:107–08. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Salazar LF. Family influences on adolescents’ sexual health: synthesis of the research and implications for clinical practice. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2006;2:369–73. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luster T, Small SA. Factors associated with sexual risk-taking behaviors among adolescents. J Marriage Fam. 1994;53:622–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzler CW, Noell J, Biglan A, Ary D, Smolkowski K. The social context for risky sexual behavior among adolescents. J Behav Med. 1994;17:419–38. doi: 10.1007/BF01858012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Ryzin MJ, Johnson AB, Leve LD, Kim HK. The number of sexual partners and health-risking sexual behavior: prediction from high school entry to high school exit. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:939–49. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9649-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill KG, Bailey JA, Hawkins JD, et al. The onset of STI diagnosis through age 30: results from the Seattle Social Development Project intervention. Prev Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0382-x. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doljanac RF, Zimmerman MA. Psychosocial factors and high-risk sexual behavior: race differences among urban adolescents. J Behav Med. 1998;21:451–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1018784326191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirby D. The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res. 2002;39:27–33. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:226–34. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Hawkins JD, Elgin J. Clinical manual of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011. Prevention of substance use and substance use disorders: Role of risk and protective factors; pp. 25–63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Oxford England: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haggerty KP, Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Harachi TW, Abbott RD. Raising Healthy Children: examining the impact of promoting healthy driving behavior within a social development intervention. Prev Sci. 2006;7:257–67. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spitalnick JS, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Brief report: Sexual sensation seeking and its relationship to risky sexual behaviour among African-American adolescent females. J Adolesc. 2007;30:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Bailey JA, et al. Person-environment interaction in the prediction of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry DB, Deptula DP, Schoeny ME. Sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy: a longitudinal analysis of risk transmission through friends and attitudes. Soc Dev. 2012;21:195–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirby D. Abstinence, sex, and STD/HIV Education programs for teens: their impact on sexual behavior, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted disease. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2007;18:143–77. [Google Scholar]