Abstract

Fatty acids (FA) are essential constituents of cell membranes, signaling molecules, and bioenergetic substrates. As CD8+ T cells undergo both functional and metabolic changes during activation and differentiation, dynamic changes in FA metabolism also occur. However, the contributions of de novo lipogenesis to acquisition and maintenance of CD8+ T cell function are unclear. Here, we demonstrate the role of FA synthesis in CD8+ T cell immunity. T cell-specific deletion of ACC1 (ACC1ΔT), an enzyme that catalyzes conversion of acetyl CoA to malonyl CoA, a carbon donor for long chain FA synthesis, resulted in impaired peripheral persistence and homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells in naïve mice. Loss of ACC1 did not compromise effector CD8+ T cell differentiation upon listeria infection, but did result in a severe defect in Ag-specific CD8+ T cell accumulation due to increased death of proliferating cells. Furthermore, in vitro mitogenic stimulation demonstrated that defective ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell blast and survival could be rescued by provision of exogenous FA. These results suggest an essential role for ACC1-mediated de novo lipogenesis as a regulator of CD8+ T cell expansion, and may provide insights for therapeutic targets for interventions in autoimmune diseases, cancer, and chronic infections.

Introduction

Upon antigen recognition, CD8+ T cells undergo rapid phenotypic changes involving metabolism, survival, and differentiation. These changes, characterized by increased cell size, proliferation, and acquisition of effector functions during differentiation into cytotoxic T cells, depend on optimal cell-cell interactions and crosstalk between multiple signaling pathways (1). Fatty acids (FA), in the form of triglycerides, phosphoglycerides, or sphingolipids, are directly involved in these cellular processes as key components of cell membranes, as signaling molecules, and as energy yielding substrates (2–5). Evidence shows that modifications in FA metabolism at both cellular and whole organism levels can influence immunity. The polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have immune regulatory roles through influence on both immune and non-immune cells (6). PUFAs reduce production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages (7, 8) and have been demonstrated to have a beneficial role in a variety of inflammatory diseases, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, Crohn’s disease, and arthritis (9). Also, modification of FA composition of the cell membrane through diet (10) or genetic manipulation (11) modulates T cell function partly through alteration of lipid raft structure and the translocation of signaling molecules. We previously demonstrated that pharmacologically enhancing fatty acid oxidation drives CD8+ T cells toward a memory fate (12). These results show a key role for FA metabolism as a potential cell-intrinsic determinant of immune outcomes. Despite these findings, it remains unclear how direct regulation of intracellular FA homeostasis affects CD8+ T cell activation, proliferation, and effector differentiation because the upstream molecular regulators have not yet been investigated.

Acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC) catalyzes conversion of acetyl CoA to malonyl CoA, which regulates both biosynthesis and breakdown of long chain fatty acids. Two isozymes, ACC1 and ACC2, mediate distinctive physiological functions within the cell, with ACC1 localized primarily to the cytosol and ACC2 to the mitochondria (13). Malonyl CoA produced in the cytosol by ACC1 serves as a carbon donor for long chain fatty acid synthesis mediated by fatty acid synthase (FASN) (14), whereas malonyl CoA synthesized by ACC2 anchored along the mitochondria surface, works as an inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1), regulating transport of long chain fatty acid into mitochondria for subsequent β-oxidation (15–18).

Due to its role in fatty acid metabolism, ACC1 has been considered a good target for intervention in metabolic syndromes and cancers. Earlier studies showed that specific deletion of ACC1 in liver (19) or adipose tissues (20) resulted, respectively in reduced de novo fatty acid synthesis and triglyceride accumulation, or skeletal growth retardation, suggesting functional importance of ACC1 for both lipogenesis and cellular homeostasis. Also, aberrantly increased ACC1 or FASN expression/activity have been observed in metastatic cancer (14, 21–23), and effective interventions against tumorigenesis with ACC1 and FASN inhibitors (24, 25) imply ACC1 may regulate cell differentiation, transformation, or fate. Combined, previous studies support a key role for ACC1 in lipid metabolism and cell fate regulation, but the role of ACC1 in lymphocyte biology is completely unknown.

Here we have demonstrated the crucial role for ACC1 in processes involved in the acquisition and/or maintenance of T cell fate. T cell-specific deletion of ACC1 impaired T cell persistence in the periphery, and homeostatic proliferation in naïve mice. ACC1 appeared dispensable for acquiring CD8+ T cell effector functions upon listeria infection, but played an indispensable role in Ag-specific CD8+ T cell accumulation by influencing survival of proliferating cells. Further, in vitro analysis demonstrated that de novo lipogenesis is necessary for blastogenesis and sustaining proliferation of CD8+ T cells under mitogenic conditions. Provision of exogenous FA was sufficient to rescue defective cell growth and accumulation of ACC1-deficient CD8+ T cells, emphasizing the importance of de novo lipogenesis for regulating optimal T cell blastogenesis and survival.

Materials and Methods

Mice

ACC1f/f mice (from Dr. David E. James, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Australia) on C57BL/6 background were crossed to Cd4-Cre mice. ACC1f/+Cd4-Cre+ or ACC1f/fCd4-Cre− littermates (WT) were used as controls in all experiments. In addition, ACC1f/f Cd4-Cre mice (ACC1ΔT) were crossed with Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I) mice to generate ACC1f/f Cd4-Cre OT-I (CD45.2+, ACC1ΔT OT-I) mice. A further cross with CD45.1+ or CD90.1+ C57BL/6 mice produced CD45.1+/2+ or CD90.1+ WT OT-I mice. B6.Ly5.2/Cr (CD45.1 congenic) mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). All mice were maintained in specific pathogen free facilities at the University of Pennsylvania. Mice and tissues collected from mice were maintained in strict accordance with University of Pennsylvania policies on the humane and ethical treatment of animals.

Mononuclear cell isolation, cell purification, and flow cytometry

Mononuclear cells were prepared and stained for flow cytometric analysis as described elsewhere (26). Thymus, spleen, peripheral lymph nodes (pLNs), and mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs) were removed and homogenized through 70 uM of nylon mesh, and the resultant cell suspension pelleted by centrifugation. RBCs were lysed, and remaining cells washed three times and counted. Absolute cell numbers were calculated based on the percentage of specific T or B cells from the total cell population acquired as determined by flow cytometric analysis.

For intracellular cytokine staining, single-cell suspensions from spleens were cultured at 37°C in complete RPMI 1640 supplemented with Golgiplug (BD Biosciences) in the presence of SIINFEKL for 5 hrs. After surface staining with anti-CD44 and anti-CD8 Abs, cell suspensions were fixed and permeabilized by Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) followed by staining with anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2) Abs. Anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-CD71 (R17217), anti-CD98 (RL388), anti-CD127 (A7R34), anti-Thy-1.2 (53-2.1), anti-CD107a (1D4B), anti-T-bet (4B10), anti-emoes (Dan11mag), anti-IFN-γ, and anti-CD107a (1D4B) antibodies were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-KLRG-1 (2F1), and anti-CD62L (MEL14) antibodies to were from BioLegend. Anti-granzyme B antibody was purchased from Invitrogen. Stained cells were collected with an LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

For naïve cell purification, mononuclear cells from spleen and lymph nodes were enriched for CD8 using magnetic separation beads (Miltenyi Biotec). After MACS enrichment, cells were stained with anti-CD44, CD62L, CD25, CD8, and CD4 antibodies to further sort out naïve CD8+ T cells (CD44lowCD62LhighCD25neg) by FACSAria (BD Biosciences).

Quantification of newly synthesized long chain fatty acids

FACS-purified naïve WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells were activated with PMA and ionomycin for 24 hrs in the presence of deuterium oxide (D2O, 5% final concentration). Culture medium was collected, cells were harvested and counted, and lipids were extracted to analyze newly synthesized fatty acids as described in detail elsewhere (27). Briefly, C-17 heptadecanoic acid was added to cell pellets as an internal standard for fatty acids. Cells were dried and lipids extracted using chloroform:methanol. The lipid extract was saponified with 1 mL 0.3N KOH-ethanol at 60°C for 1 hr. Fatty acids were derivatized to methyl ester forms with methanolic boron trifluoride, extracted into hexane and injected into an Agilent 7890A/5975 GC/MS fitted with a DB-5MS column. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAMES) were run in split mode (1 μl at a split of 1:10) with the following settings: inlet temperature, 250 °C; flow rate, 1 ml/min; transfer line 280 °C; MS quadrupole, 150°C; MS source, 230 °C; oven set at 150 °C initially, ramped to 200 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and then ramped to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C /min (22 min total run time). A palmitate standard was used to quantitate palmitate, stearate and oleate after applying a response correction. Quantification of the area under the curve for selected ions was done with Chemstation software.

Lymphopenia-induced proliferation

FACS-purified naïve CD8+ T cells from ACC1f/fCd4-Cre (ACC1ΔT) and their wild-type littermates (WT) or from CD90.1+ congenic mice were labeled with CFSE (carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester), and 0.8 ×106 cells of WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells per mouse were injected i.v. into hosts irradiated one day earlier with 750 rads. The same number of CD90.1+ CD8+ T cells were co-transferred per mouse. After 14 days, host spleen and lymph node cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

LmOVA infection

1×103 ACC1ΔT OT-I (CD45.2+) and their wild-type (WT) littermates (CD45.2+ or CD45.1/2+) cells were transferred intravenously to 6–8-wk-old CD45.1+ recipient mice. Mice were then infected i.v. with 1×106 CFU of recombinant attenuated L. monocytogenes (LmOVA) (12, 28).

BrdU labeling

For in vivo labeling, BrdU (1 mg/mouse) was injected intraperitoneally into mice. For in vitro labeling, BrdU (1 mM/mL) was added to cell culture for 1 hr. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences).

Cell culture and fatty acids preparation

FACS-purified naïve CD8+ T ells (CD25negCD44lowCD62Lhigh) were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol in 96-well plates. Cells were activated with Dynabeads mouse T-activator CD3/28 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol in the presence 100 U/ml of human IL-2 (PeproTech).

Sodium palmitate and oleic acid (Sigma) were dissolved in methanol at 25 mM. 25 mM stocks were diluted ten-fold in PBS containing 0.9% fatty acid free BSA (Roche). These 2.5 mM (100X) stocks were thoroughly mixed by vortexing and incubated at 37 degrees for one hour prior to use.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The mixed-effect model or the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used for comparison of the two groups using customized routines written in the statistical programming language R (version 2.15.0). In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

ACC1 deficiency compromises de novo lipogenesis

Mitogenic signals, like those encountered by CD8+ T cells during pathogenic infections, induce lipogenesis in T cells (29–31). To begin to explicitly characterize the functional importance of FA metabolism to CD8+ T cell function, we first assayed gene induction of the acetyl CoA carboxylases (ACC), ACC1 and ACC2, during primary expansion of CD8+ T cells. Quantitative PCR analysis of purified naïve versus effector CD8+ T cells 6 days post listeria infection showed significant induction of ACC1, but not ACC2 mRNA (Fig. 1A). This result suggests a potentially important role for ACC1 in CD8+ T cell activation and effector differentiation. Therefore, we chose to focus on investigating the T cell-intrinsic role of ACC1 in immune responses.

Figure 1. ACC1 deficiency compromises de novo lipogenesis in T cells.

(A) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of ACC1 and ACC2 gene expression from naïve and effector CD8+ T cells after LmOVA infection. Mice were infected with LmOVA one day following transfer of 1 × 103 OT-I cell per mouse, and donor cells were FACS sorted six days later. Results are presented relative to 18S (n=4). (B) Generation of mice with T cell-specific deletion of the ACC1 gene and confirmation of gene deletion in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Schematic presentation of the floxed allele and PCR analysis of ACC1 deletion in genomic DNA in FACS-purified CD4+, CD8+, B220+, CD11b+ cells from ACC1f/f (WT) and ACC1f/f Cd4-cre (ACC1ΔT) mice. IL-2 was an internal control. (C) Quantification of newly synthesized long-chain fatty acids in WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry 24 hrs post activation in vitro. (WT n=6, ACC1ΔT n=4) (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001)

Complete lack of ACC1 in mice is lethal at approximately embryonic day 8.5 (32). In order to study the role of ACC1 specifically in T cells in vivo, we crossed mice in which exons 42 and 43 of the gene encoding ACC1, Acaca, are flanked by loxP sites to mice carrying the Tg(Cd4-Cre)1Cwi transgene to induce T cell–specific deletion (Fig. 1 B). Efficient and specific deletion of targeted exons 42 and 43 in peripheral T cells was demonstrated by PCR of genomic DNA (Fig. 1B). Additionally, we observed that ACC1 deletion did not affect mRNA expression of ACC2, FAS, or SCD-1 in naïve CD8+ T cells (data not shown). We next analyzed the capacity of de novo lipogenesis of activated T cells isolated from ACC1f/f-Cd4Cre mice (ACC1ΔT) by quantifying newly synthesized long chain fatty acids by GC/MS analysis (Fig. 1C). New synthesis of C16:0 and C18:1 was reduced 2- and 22-fold, respectively, in activated ACC1ΔT compared to WT T cells, demonstrating that deletion of ACC1 in T cells has functional effects on de novo lipogenesis. However, the total quantity of each fatty acid, C16:0, C18:0, or C18:1, was not significantly different between WT and ACC1ΔT T cells at 24 hours post-activation, possibly owing to the small proportion of newly synthesized fatty acids compared to the total amount of each fatty acid.

Loss of ACC1 impairs T cell homeostasis in the periphery

To examine the effects of ACC1 deletion on peripheral T cell homeostasis, we analyzed the frequency and numbers of T cells in thymus, spleen, and peripheral lymph nodes (pLN) isolated from 7 week-old ACC1ΔT and WT littermate mice. While the CD4+ and CD8+ profiles of thymocytes from ACC1ΔT mice were unremarkable, frequencies and numbers of CD8+ T cells in spleens and pLNs were dramatically reduced in ACC1ΔT compared to WT controls (Fig. 2, A and B). Much less but still significant reduction in CD4+ T cells was also observed in the ACC1ΔT mice, while peripheral ACC1ΔT B cell numbers were normal (Fig. 2, A and B). To determine whether ACC1 deletion resulted in cellular phenotypic differences, we analyzed expression of various surface markers. Expression of activation markers CD69, CD25, and CD127, as well as expression of transferrin (CD71) and amino acid transporter (CD98) on ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells was similar to levels expressed by cells from littermate control cells (Fig. 2 C). However, further phenotypic analysis of peripheral T cells in ACC1ΔT mice showed a significantly lower proportion of activated-memory phenotype (CD44hi) in CD8+ T cells compared to littermate controls (Fig. 2D), suggesting that ACC1 is necessary to acquire and/or maintain an activated phenotype. Together, these observations suggest a general role for ACC1 in peripheral T cell maintenance, with particular importance to the CD8+ T cell compartment.

Figure 2. Loss of ACC1 impairs T cell homeostasis in the periphery.

(A) Frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the thymus, spleen, peripheral lymph nodes (pLNs), and blood from naive ACC1ΔT and WT littermate mice (7 weeks old). Shown are representative dot plots from five independent experiments (B) Numbers of isolated cells in the spleen and pLNs from ACC1ΔT mice and WT littermates (means±standard deviation) (C) Expression of various surface markers in splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from WT and ACC1ΔT mice at 7 weeks old. Results are representative of at least 9 mice per group analyzed. (D) CD44 and CD62L expression profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and their frequencies in the spleen; results are representative of at least 9 mice per group. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001)

Loss of ACC1 impairs CD8+ T cell persistence and homeostatic proliferation

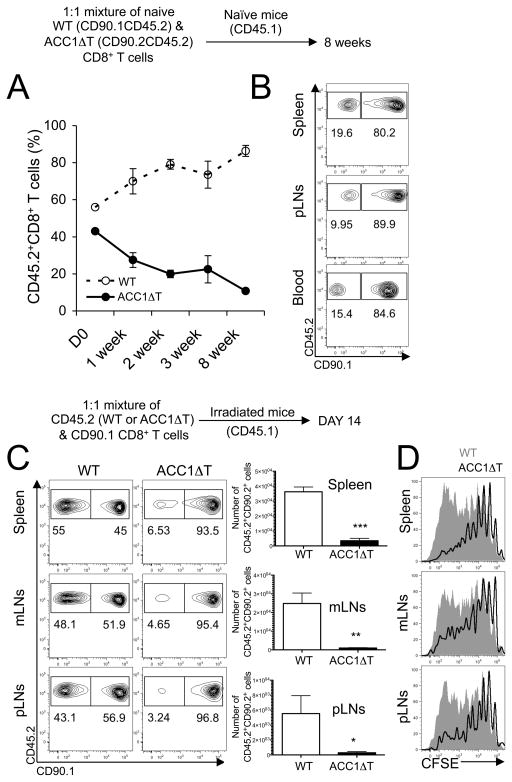

To account for possible cell non-autonomous and/or thymic feedback effects on ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell hypocellularity, we examined the persistence of naïve CD8+ T cells in the periphery. FACS-sorted naïve (CD44lowCD62LhighCD25neg) WT congenic (CD90.1+CD45.2+) and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (CD90.2+CD45.2+) were co-transferred into naïve recipient mice (CD45.1+) in equal numbers, and donor-derived CD8+ T cells were longitudinally analyzed to measure the ratio of the WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells in the blood. ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell numbers decayed faster than those of WT CD8+ T cells, thus the ratio of WT CD8+ T cells to ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells increased over time (Fig. 3A). Also, consistent with previous observations of naïve ACC1ΔT mice (Fig. 2B), five times fewer ACC1ΔT than WT CD8+ T cells were recovered from spleens 8 weeks post-transfer (Fig. 3B), suggesting defective survival and/or turnover of naïve ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells when in a T cell-replete (competitive) environment. We next examined the capacity of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells to persist and expand in a lymphopenic environment. CFSE-labeled FACS-sorted naïve WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (CD90.2+CD45.2+) were transferred into irradiated congenic recipient mice (CD90.2+CD45.1+) along with reference cells (naïve CD90.1+CD45.2+CD8+ T cells) and harvested 14 days later. Consistent with the previous result (Fig. 3A), ten times fewer ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells were recovered from the spleen (Fig. 3C). These results, along with the diminished CFSE dilution (Fig. 3D), suggest a defect in survival and/or proliferation of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells under lymphopenic condition.

Figure 3. Loss of ACC1 impairs CD8+ T cell persistence and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery.

(A–B) 1:1 mixture of 2 × 106 sorted naïve (CD44lowCD62LhighCD25neg) WT (CD90.1+CD45.2+) and ACC1ΔT (CD90.2+CD45.2+) CD8+ T cells were transferred into naïve congenic recipient mice (CD45.1+). Mice were bled at indicated time points and mononuclear cells were surface stained (n=3). (A) Longitudinal analysis of the frequency of WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells in the blood and (B) in various tissues 8 weeks post cell transfer (C) Lymphopenia-induced proliferation of WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells from the spleen, mesenteric LNs (mLNs), and pLNs was measured 14 days post transfer of CFSE-labeled naïve WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (CD45.2+) into irradiated host mice (CD45.1+). Naïve CD90.1+ CD8+ T cells were co-transferred as reference cells. Dot plots show the frequency of WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells in comparison to that of reference cells from the same recipient mouse (n=5, one representative result shown from three independent experiments). (D) Histograms show CFSE dilution of transferred WT (grayed area) and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (black line) from the spleen, mLNs, and pLNs. Graphs represent numbers of isolated WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells from indicated tissues (means±standard deviation, n=5) One representative result shown from three independent experiments. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001)

ACC1 is required for accumulation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells during LmOVA infection

To investigate whether ACC1 is required for CD8+ T cell responses during infection, we adoptively transferred chicken ovalbumin-specific TCR transgenic (OT-I) CD8+ T cells isolated from either WT or ACC1ΔT mice into recipient mice and examined their responses to listeria-OVA (LmOVA) infection. LmOVA infection results in robust expansion of CD8+ T cells, accompanied by effector differentiation (12). On day 7 post-infection, donor-derived WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells were identified by co-staining for Kb/OVA tetramer and the donor congenic marker CD45.2. Splenic frequency of ACC1ΔT OT-I within the CD8+ T cell population was five times lower than for WT controls, with eight times fewer total ACC1ΔT OT-I cells recovered, demonstrating a severe defect in accumulation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells upon LmOVA infection (Fig. 4A). A similar result was observed in the blood (data not shown), suggesting that reduced accumulation of ACC1ΔT OT-I cells in the spleen was not caused by preferential sequestration in other tissues. Additionally, we confirmed that defective accumulation of ACC1ΔT OT-I cells after LmOVA infection was cell-intrinsic, and not related to differences in abundance of antigens or other environmental factors affecting CD8+ T cell responses, by co-transferring WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells into the same recipient mice in equal numbers (Supplementary figure 1).

Figure 4. ACC1 is required for accumulation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells during LmOVA infection.

1 × 103 WT OT-I or ACC1ΔT OT-I (CD45.2+) cells were transferred into CD45.1+ recipients and infected with LmOVA. Seven days post-infection, single cells were prepared from spleens and stained for various surface markers, cytokines, and transcription factors. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n=8). (A) Dot plots show donor cells by CD45.2 and Kb/OVA tetramer (numbers indicate percent of total CD8+ T cells that are host- or donor-derived). Graph represents number of WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells (means ± standard deviation). (B) Dot plots show frequency of IFN-γ-producing WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells. Graphs represent number of IFN-γ producing WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells (means ± standard deviation). (C) The expression of surface markers, granzyme B, and transcription factors was determined in WT (grayed area) and ACC1ΔT OT-I (black line) cells. (***p < 0.0001)

Despite diminished Ag-specific ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell numbers, ACC1ΔT effector differentiation on a per cell basis, as determined by expression of the degranulation marker CD107a, the inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ, and granzyme B, was similar to WT OT-I cells (MFI of IFN-γ WT OT-I: 2194 ± 474; ACC1ΔOT-I: 1772 ± 581; p=0.2; MFI of granzyme B WT OT-I: 280 ± 22; ACC1ΔOT-I: 286 ± 18; p=0.6) (Fig. 4B and 4C). Additionally, T-bet and eomes, the T-box transcription factors essential for acquiring effector CD8+ T cell functions (33), were expressed normally in ACC1ΔT OT-I cells (Fig. 4B). Further phenotypic analysis of surface marker expression showed normal up-regulation of CD62L, CD44, CD71, CD98, and KLRG-1, but slightly less down-regulation of CD127 (MFI of WT OT-I: 118.98 ± 17, ACC1ΔOT-I 137.6 ± 7, p=0.003) (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that ACC1 is indispensable for Ag-specific CD8+ T cell accumulation during infection, but is dispensable for acquiring CD8+ T cell effector functions.

ACC1 is essential for survival of proliferating CD8+ T cells

To directly address the proliferation and survival capacity of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells in vivo, we analyzed transferred WT or ACC1ΔT OT-I cells five days post-LmOVA infection, at the peak of Ag-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation by injecting mice with BrdU to pulse proliferating cells. While the frequency of ACC1ΔT OT-I cells within the total CD8+ T cell population was two times lower than for WT, the frequency of BrdU incorporation by WT and ACC1ΔT OT-I cells was similar (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that although ACC1ΔT OT-I cells are capable of synthesizing DNA, most of the BrdU-incorporating daughter cells fail to survive. To further examine whether ACC1 is directly involved in survival of CD8+ T cells, we analyzed the number of live cells under both non-mitogenic and mitogenic conditions in vitro. Naive ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells exhibited normal survival in the presence of IL-7 for three days (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, no substantial differences were observed in live cell counts up to 24 hours post-activation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (prior to the first cell division) (Fig. 5C). However, at 72 hours post-activation, when all the cells have undergone several cycles of proliferation, significant defects were observed in both cell numbers and the dilution profile of proliferation dye (Fig. 5D). The average ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell underwent fewer cycles of proliferation compared to WT CD8+ T cells. These results demonstrated that deletion of ACC1 renders CD8+ T cells sensitive to cell death upon mitogenic stimulation.

Figure 5. ACC1 is essential for survival of proliferating CD8+ T cells.

(A) OT-I cells (1 × 104) from WT and ACC1ΔT (CD45.2+) mice were transferred into CD45.1+ recipients and infected with LmOVA one day later. Mice were injected with BrdU i.p. on day 5 post-infection. One hour post-BrdU injection, spleens were harvested and CD8+CD45.2+ donor-derived cells were analyzed for BrdU incorporation. Numbers indicate the percentage of BrdU positive cells among the donor CD45.2+ cells or donor CD45.2+ cells among CD8+ T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n=3~5/group/experiment). (B) FACS-sorted naïve WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (CD44lowCD62LhighCD25neg) were cultured alone or in the presence of IL-7 (1 ng/mL) for three days. Results are presented as relative live cell counts to those of WT cells cultured without anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody stimulation (means ± standard deviation). Shown here is one representative result from at least four independent experiments. (C) FACS-sorted naïve WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (CD44lowCD62LhighCD25neg) were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies along with IL-2 for 24 hrs. Cells cultured without anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies were supplemented with IL-7 instead. Graph shows number of live cells (means ± standard deviation, n=4). (D) Histograms show dilution of cellular proliferation dye of WT (grayed area) and ACC1ΔT CD8+ (black line) T cells 72 hrs post-activation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Results are presented as live cell counts relative to those of WT cells cultured without anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody stimulation (means ± standard deviation). One representative result shown from at least three independent experiments (***p < 0.0001)

Exogenous fatty acids rescue survival and proliferation of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells under mitogenic conditions

Lipid macro-molecules are a major physical constitute of cells (2, 4). Therefore, it is logical to speculate that limiting these “building block” molecules may have negative effects on survival during cell division. We tested if fatty acid supplementation could rescue survival and proliferation of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells under mitogenic conditions. We provided exogenous long-chain fatty acids to proliferation dye-labeled WT and ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells during activation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, and analyzed cell expansion 60 hrs later. Cells were also pulsed with BrdU for one hour before harvest to determine the frequency of proliferating cells in a set period of time. Consistent with in vivo results (Fig. 5A), significantly fewer ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells were recovered when cultured without FA despite frequencies of BrdU-incorporating cells similar to WT CD8+ T cells. However, overall cell expansion of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells was restored to WT levels when supplemented with exogenous FA, as evidenced by increased cell numbers and dilution of cellular proliferation dye (Fig. 6A). A 1:1 mixture of palmitic and oleic acids more dramatically rescued ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell expansion than addition of each fatty acid alone (data not shown).

Figure 6. Exogenous fatty acids rescue survival and proliferation of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells under mitogenic conditions.

(A) FACS-sorted naïve WT or ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells were labeled with proliferation dye and cultured with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies alone or with 25uM FA supplement for 60 hrs in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL), and were then pulsed with BrdU for one hour, harvested, and stained for BrdU incorporation. Dot plots show dilution of proliferation dye and BrdU incorporating cells. Numbers in dot plots indicate percentage of BrdU incorporating cells in each group. Shown here is one representative result out of three independent experiments. (B) Analysis of cell enlargement by FACS 24hrs post activation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies alone or FA supplement. Cells were gated on live events (TO-PRO-3neg). Histograms show forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) of live WT (grayed area) and ACC1ΔT CD8+ (black line) T cells. Graphs summarize changes in FSC and SSC upon FAs supplement. Shown here is one representative result out of three independent experiments. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 and ***p < 0.0001)

We further characterized the contribution of exogenous FA in ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells during activation prior to cell division. Analysis of forward scatter (FSC) (an assessment of cell size) and side scatter (SSC) (an assessment of granularity) of cells at 24 hours post-activation showed that while exogenous FA did not affect SSC of WT CD8+ T cells, it significantly increased the FSC and SSC of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting that FA synthesis is an essential prerequisite for blastogenesis. Despite the atrophy observed in ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells, they appeared to be capable of processing mitogenic signals normally at some level, as evidenced by up-regulation of CD69, CD25, CD71, and CD98, with exception of CD44 up-regulation (Supplementary figure 2). Together, these data suggest that de novo lipogenesis is a limiting factor for proper cell growth and sustained proliferation of CD8+ T cells upon activation.

Discussion

The importance of lipogenic enzymes in regulating the proliferative capacity and survival of cancer cells has previously been described (25, 34, 35). However, the role of ACC1 in the survival and proliferation of primary T cells has remained poorly understood. In this study, we demonstrated the importance of de novo lipogenesis to optimal T cell function under both homeostatic and inflammatory conditions. We have found that FA synthesis throughout the lifespan of T cells is required for regulating viability and proliferation.

ACC1 in quiescent T cells

Antigen-inexperienced naïve T cells circulate through the blood and peripheral lymphoid organs, are small in size and have low metabolic activity. Their survival depends on TCR interactions with self-peptide:MHC and the availability of IL-7, and is shaped by growth factors and nutrients related to metabolic fitness (36). We were interested in determining whether these processes are actively influenced by de novo fatty acid synthesis. Deletion of ACC1 in the T cell compartment resulted in diminished T lymphocyte cellularity in naïve mice (Fig. 2 A–D), and shorter life span of ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells transferred into naïve WT mice (Fig. 3A), while ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell homing/distribution, cell size, surface marker expressions (Fig. 2 A–C) and responsiveness to IL-7 in vitro (Fig. 5B) were not affected. T cells undergo proliferation in the periphery in response to self-peptide:MHC in addition to IL-7 and/or IL-15 under non-inflammatory conditions. Cell divisions are observed in both naïve and activated/memory compartments of T cells in WT mice (37), though the turnover of naïve cells is much slower. Reduced proportions of CD44high ACC1ΔT cells along with a defect in lymphopenia-induced proliferation suggest a possible perturbation of homeostatic proliferation of T cells by a loss of ACC1 function. However, in our experimental models, homeostatic proliferation reflects both proliferation and survival of naïve CD8+ T cells, rather than identifying a single mechanism. Recently, Kidani et al. showed that deletion of scap, a SREBP-cleavage-activating protein, that regulates the processing and transcriptional activity of SREBP1 and SREBP2 in CD8+ T cells influences neither cellularity nor homeostatic proliferation, while resulting in significant reduction in cellular quantity of cholesterol and long chain fatty acids (29). As one of the transcription factors upstream of ACC1 expression, SREBP broadly impacts FA and cholesterol biosynthesis through interactions with other pathways, such as LXRα, Akt, and mTOR, to integrate metabolic signals (38–40). However, because ACC1 is an upstream molecular regulator of long chain fatty acid synthesis, its deletion has a more specific effect on lipid metabolism. Therefore, the differences we observed between scapΔT and ACC1ΔT mice might be results of subtle differences in lipid composition and the micro-architecture of membrane, or a compensatory alteration in signaling pathways involved in T cell homeostasis.

ACC1 in proliferating T cells

Proliferating T cells need considerable energy and metabolites for biosynthetic pathways to support increased requirements for structural membrane and signaling molecules during cell cycle progression (2, 4). For example, proliferating T cells employ highly active fatty acid synthesis pathways and FA incorporation into complex lipids, and imbalances in synthesis or turnover of lipids affect cell growth and viability (4). Accordingly, we observed that Ag-specific ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cell accumulation is impaired during responses to bacterial infection despite normal progression to S phase of the cell cycle. This result shows synthesis of fatty acids per se is a limiting factor in survival of proliferating CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4 and 5). Newly synthesized FA in the form of phospholipids tends to partition into detergent-resistant membrane microdomains or rafts (41). The regulatory role of specific lipids clusters in the membrane has been implicated in a number of processes, including signal transduction, cell-cell interactions, and cell division. Previously, Emoto et al. showed that localized production of the phospholipid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), is required for proper completion of cytokinesis, possibly because formation of a unique lipid domain in the cleavage furrow membrane is necessary to coordinate contractile rearrangement (42). Therefore, it seems reasonable to speculate that progression toward cytokinesis may be blocked in ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells due to lack of biomass molecules and subsequent membrane remodeling. Also, our in vitro analysis showed a loss of ACC1 rendered CD8+ T cells incapable of blasting, and subsequently, resulted in lower proliferative capacity and viability (Fig. 5D), suggesting defects in earlier activation pathways, which could be rescued by FA provision.

As shown with defective ACC1ΔT CD44 expression, some signaling pathways reflective of cellular activation and proliferation remained defective in ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells even with provision of supplemental FA. Further studies of the role of de novo FA synthesis in the dynamics of membrane lipid clustering and remodeling during early blastogenesis will help us further elucidate the regulatory role of lipids in initiating T cell responses.

Additionally, our data show that ACC1ΔT CD8+ T cells are not defective in expressing T-bet, IFN-γ, and granzyme B upon Lm infection (Fig. 4 B and C), suggesting there are de novo lipogenesis-independent pathways involved in acquiring effector T cell functions that are distinct from regulation of blastogenesis and viability. Metabolic requirements for acquiring or maintaining T cell function are of interest in understanding the mechanisms regulating immune responses, and some studies have implicated metabolic reprogramming in this context (29, 43, 44). Our data suggests that de novo lipogenesis per se is not a prerequisite of effector CD8+ T cell differentiation, but rather supports accumulation of cells already committed. Further studies on lipid metabolism in the context of other metabolic processes involved in anabolic and catabolic metabolism throughout T cell lifespan will help us delineate intertwined mechanisms in CD8+ T cell metabolism and differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Millar at the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism (IDOM) Metabolic Tracer Resource and staff members of Path BioResource in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at University of Pennsylvaina for technical helps. We also thank Nick Dang for assistance with genotyping.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI064909 (to Y.C.), AI083022, AI082630, AI0955608 (to E.J.W.), the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM), MEST, Korea (No. K13050 to Y.C.), and NHMRC Program grant (to D.J.). IDOM Metabolic Tracer Resource was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health Grants 8UL1TR000003.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Acetyl CoA

Acetyl coenzyme A

- Malonyl CoA

Malonyl coenzyme A

- FAS

Fatty acid synthase

- SCD-1

Stearoyl CoA desaturate-1

- FA

fatty acids

- LmOVA

attenuated L. monocytogenesOVA

References

- 1.van Stipdonk MJ, Hardenberg G, Bijker MS, Lemmens EE, Droin NM, Green DR, Schoenberger SP. Dynamic programming of CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:361–365. doi: 10.1038/ni912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natter K, Kohlwein SD. Yeast and cancer cells - common principles in lipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1831:314–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. The Ceramide-centric universe of lipid-mediated cell regulation: stress encounters of the lipid kind. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25847–25850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robichaud PP, Boulay K, Munganyiki JE, Surette ME. Fatty acid remodeling in cellular glycerophospholipids following the activation of human T cells. J Lipid Res. 54:2665–2677. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake DR, 3rd, Braciale TJ. Cutting edge: lipid raft integrity affects the efficiency of MHC class I tetramer binding and cell surface TCR arrangement on CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:7009–7013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang MJ, Spite M. Resolvins: anti-inflammatory and proresolving mediators derived from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Annu Rev Nutr. 32:203–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Y, Jiang W, Spinetti T, Tardivel A, Castillo R, Bourquin C, Guarda G, Tian Z, Tschopp J, Zhou R. Omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation and metabolic disorder through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 38:1154–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudert CA, Weylandt KH, Lu Y, Wang J, Hong S, Dignass A, Serhan CN, Kang JX. Transgenic mice rich in endogenous omega-3 fatty acids are protected from colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11276–11281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601280103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan YY, McMurray DN, Ly LH, Chapkin RS. Dietary (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids remodel mouse T-cell lipid rafts. J Nutr. 2003;133:1913–1920. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim W, Fan YY, Barhoumi R, Smith R, McMurray DN, Chapkin RS. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress the localization and activation of signaling proteins at the immunological synapse in murine CD4+ T cells by affecting lipid raft formation. J Immunol. 2008;181:6236–6243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, Jones RG, Choi Y. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Elheiga L, Brinkley WR, Zhong L, Chirala SS, Woldegiorgis G, Wakil SJ. The subcellular localization of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1444–1449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chirala SS, Wakil SJ. Structure and function of animal fatty acid synthase. Lipids. 2004;39:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ha J, Lee JK, Kim KS, Witters LA, Kim KH. Cloning of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase-beta and its unique features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11466–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu-Elheiga L, Almarza-Ortega DB, Baldini A, Wakil SJ. Human acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. Molecular cloning, characterization, chromosomal mapping, and evidence for two isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10669–10677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakil SJ, Stoops JK, Joshi VC. Fatty acid synthesis and its regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:537–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakil SJ, Abu-Elheiga LA. Fatty acid metabolism: target for metabolic syndrome. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S138–143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800079-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao J, DeMayo FJ, Li H, Abu-Elheiga L, Gu Z, Shaikenov TE, Kordari P, Chirala SS, Heird WC, Wakil SJ. Liver-specific deletion of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 reduces hepatic triglyceride accumulation without affecting glucose homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8552–8557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao J, Yang T, Gu Z, Heird WC, Finegold MJ, Lee B, Wakil SJ. aP2-Cre-mediated inactivation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 causes growth retardation and reduced lipid accumulation in adipose tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17576–17581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909055106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhajda FP. Fatty-acid synthase and human cancer: new perspectives on its role in tumor biology. Nutrition. 2000;16:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD, Pasternack GR. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6379–6383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graner E, Tang D, Rossi S, Baron A, Migita T, Weinstein LJ, Lechpammer M, Huesken D, Zimmermann J, Signoretti S, Loda M. The isopeptidase USP2a regulates the stability of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alli PM, Pinn ML, Jaffee EM, McFadden JM, Kuhajda FP. Fatty acid synthase inhibitors are chemopreventive for mammary cancer in neu-N transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2005;24:39–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menendez JA, Vellon L, Colomer R, Lupu R. Pharmacological and small interference RNA-mediated inhibition of breast cancer-associated fatty acid synthase (oncogenic antigen-519) synergistically enhances Taxol (paclitaxel)-induced cytotoxicity. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:19–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, Reinke EK, Zozulya AL, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection in the CNS suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and Th17 responses in an IFN-gamma-independent manner. J Immunol. 2008;181:6201–6212. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee WN, Bassilian S, Guo Z, Schoeller D, Edmond J, Bergner EA, Byerley LO. Measurement of fractional lipid synthesis using deuterated water (2H2O) and mass isotopomer analysis. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:E372–383. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.3.E372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce EL, Shen H. Generation of CD8 T cell memory is regulated by IL-12. J Immunol. 2007;179:2074–2081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidani Y, Elsaesser H, Hock MB, Vergnes L, Williams KJ, Argus JP, Marbois BN, Komisopoulou E, Wilson EB, Osborne TF, Graeber TG, Reue K, Brooks DG, Bensinger SJ. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are essential for the metabolic programming of effector T cells and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 14:489–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anel A, Naval J, Gonzalez B, Torres JM, Mishal Z, Uriel J, Pineiro A. Fatty acid metabolism in human lymphocytes. I. Time-course changes in fatty acid composition and membrane fluidity during blastic transformation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1044:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90076-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resch K, Bessler W. Activation of lymphocyte populations with concanavalin A or with lipoprotein and lipopeptide from the outer cell wall of Escherichia coli: correlation of early membrane changes with induction of macromolecular synthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1981;115:247–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Elheiga L, Matzuk MM, Kordari P, Oh W, Shaikenov T, Gu Z, Wakil SJ. Mutant mice lacking acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 are embryonically lethal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, Gapin L, Ryan K, Russ AP, Lindsten T, Orange JS, Goldrath AW, Ahmed R, Reiner SL. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason P, Liang B, Li L, Fremgen T, Murphy E, Quinn A, Madden SL, Biemann HP, Wang B, Cohen A, Komarnitsky S, Jancsics K, Hirth B, Cooper CG, Lee E, Wilson S, Krumbholz R, Schmid S, Xiang Y, Booker M, Lillie J, Carter K. SCD1 inhibition causes cancer cell death by depleting mono-unsaturated fatty acids. PLoS One. 7:e33823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chajes V, Cambot M, Moreau K, Lenoir GM, Joulin V. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha is essential to breast cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5287–5294. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of naive and memory T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tough DF, Sprent J. Turnover of naive- and memory-phenotype T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1127–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberle D, Hegarty B, Bossard P, Ferre P, Foufelle F. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie. 2004;86:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Griffiths B, Cully M, Wu M, Leevers S, Griffiths JR, Chung YL, Schulze A. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab. 2008;8:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen G, Liang G, Ou J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Central role for liver X receptor in insulin-mediated activation of Srebp-1c transcription and stimulation of fatty acid synthesis in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11245–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404297101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swinnen JV, Van Veldhoven PP, Timmermans L, De Schrijver E, Brusselmans K, Vanderhoydonc F, Van de Sande T, Heemers H, Heyns W, Verhoeven G. Fatty acid synthase drives the synthesis of phospholipids partitioning into detergent-resistant membrane microdomains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:898–903. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emoto K, Inadome H, Kanaho Y, Narumiya S, Umeda M. Local change in phospholipid composition at the cleavage furrow is essential for completion of cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37901–37907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, Jr, Faubert B, Villarino AV, O’Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J, Weber JD, Pearce EJ, Jones RG, Pearce EL. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Jacobs SR, Zhao Y, Rathmell JC. IL-7 promotes Glut1 trafficking and glucose uptake via STAT5-mediated activation of Akt to support T-cell survival. Blood. 2008;111:2101–2111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.