Abstract

Context:

Biochemical control reduces morbidity and increases life expectancy in patients with acromegaly. With current medical therapies, including the gold standard octreotide long-acting-release (LAR), many patients do not achieve biochemical control.

Objective:

Our objective was to demonstrate the superiority of pasireotide LAR over octreotide LAR in medically naive patients with acromegaly.

Design and Setting:

We conducted a prospective, randomized, double-blind study at 84 sites in 27 countries.

Patients:

A total of 358 patients with medically naive acromegaly (GH >5 μg/L or GH nadir ≥1 μg/L after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and IGF-1 above the upper limit of normal) were enrolled. Patients either had previous pituitary surgery but no medical treatment or were de novo with a visible pituitary adenoma on magnetic resonance imaging.

Interventions:

Patients received pasireotide LAR 40 mg/28 days (n = 176) or octreotide LAR 20 mg/28 days (n = 182) for 12 months. At months 3 and 7, titration to pasireotide LAR 60 mg or octreotide LAR 30 mg was permitted, but not mandatory, if GH ≥2.5μg/L and/or IGF-1 was above the upper limit of normal.

Main Outcome Measure:

The main outcome measure was the proportion of patients in each treatment arm with biochemical control (GH <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1) at month 12.

Results:

Biochemical control was achieved by significantly more pasireotide LAR patients than octreotide LAR patients (31.3% vs 19.2%; P = .007; 35.8% vs 20.9% when including patients with IGF-1 below the lower normal limit). In pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients, respectively, 38.6% and 23.6% (P = .002) achieved normal IGF-1, and 48.3% and 51.6% achieved GH <2.5 μg/L. 31.0% of pasireotide LAR and 22.2% of octreotide LAR patients who did not achieve biochemical control did not receive the recommended dose increase. Hyperglycemia-related adverse events were more common with pasireotide LAR (57.3% vs 21.7%).

Conclusions:

Pasireotide LAR demonstrated superior efficacy over octreotide LAR and is a viable new treatment option for acromegaly.

Acromegaly is a rare serious condition characterized by chronic hypersecretion of GH from a pituitary adenoma. GH induces the synthesis of IGF-1, and elevated GH and IGF-1 cause metabolic dysfunction and somatic growth, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Achieving and maintaining control of GH and IGF-1 reduces morbidity and restores normal life expectancy for patients with acromegaly (1, 2). First-line treatment is usually transsphenoidal surgery; however, cure rates decrease with increasing adenoma size, extrasellar extension, and cavernous sinus invasion (3), and most patients with a macroadenoma require postsurgical medical treatment to achieve disease control (4). With current medical therapies, many patients are unable to achieve a GH level below 2.5 μg/L and a normalized IGF-1 level, the composite indicator of biochemical control (5–7).

Pasireotide is a multireceptor-targeted somatostatin analog with high affinity for 4 of the 5 somatostatin receptor subtypes (sst), including sst2 and sst5, which are the most prevalent sst on GH-secreting pituitary adenomas (8). The efficacy of the twice-daily sc formulation of pasireotide has been demonstrated in patients with acromegaly (9), and a monthly long-acting-release (LAR) formulation of pasireotide has been developed (10). Here we present results from a prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of pasireotide LAR vs the current standard of care, octreotide LAR, in medically naive patients with acromegaly.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Adult patients with active acromegaly confirmed by a 2-hour 5-point mean GH level >5 μg/L or lack of suppression of GH nadir to <1 μg/L after an oral glucose tolerance test and elevated IGF-1 for age- and sex-matched controls were enrolled. Patients could have had ≥1 pituitary surgery but not have been medically treated for acromegaly. De novo patients with a pituitary adenoma visible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) but who refused pituitary surgery or for whom surgery was contraindicated were also eligible.

Key exclusion criteria were previous treatment with somatostatin analogs, dopamine agonists, or a GH receptor antagonist; compression of the optic chiasm causing any visual field defect; a requirement for surgical intervention for relief of any sign or symptom associated with tumor compression; pituitary irradiation within the last 10 years; significant cardiovascular morbidity and/or liver disease; symptomatic cholelithiasis; and HbA1c >8%. Significant cardiovascular morbidity was defined as congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV), unstable angina, sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, clinically significant bradycardia, advanced heart block, or a history of acute myocardial infarction within the 6 months preceding enrollment.

Study design

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, 12-month study. Eligible patients were randomized 1:1 to pasireotide LAR 40 mg or octreotide LAR 20 mg every 28 days and were stratified into 2 groups: 1) after pituitary surgery or 2) de novo. A dose increase to pasireotide LAR 60 mg or octreotide LAR 30 mg was permitted, but not mandatory, at month 3 or 7 based on biochemical response (mean GH ≥2.5 μg/L and/or IGF-1 above the upper limit of normal [ULN]). Dose decreases were permitted for tolerability, and the dose could be increased upon resolution. Because the 2 treatments differ in appearance, injections were administered on site by an independent, unblinded nurse to ensure that patient and investigator were blinded to treatment.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and an independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each study site approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00600886).

Study objectives and endpoints

The primary objective was to show superiority of pasireotide LAR over octreotide LAR in terms of biochemical control (proportion of patients achieving GH < 2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 for age and sex) at month 12. Secondary objectives included determining proportion of patients achieving GH <2.5 μg/L; proportion of patients achieving normal IGF-1 for age and sex; mean GH and IGF-1 levels over time; decrease in tumor volume; change in signs, symptoms, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL); and safety.

The 5-point mean GH levels (2-hour curve) before drug injection and IGF-1 levels were assessed at baseline and months 3, 6, 9, and 12. Five symptoms of acromegaly (headache, fatigue, perspiration, paresthesia, and osteoarthralgia) were scored from 0 (no symptom) to 4 (very severe) each month. HRQoL was assessed using the AcroQoL questionnaire (11), a 22-item instrument resulting in scores ranging from 0 (worst HRQoL) to 100 (best HRQoL).

Gadolinium-enhanced pituitary MRI was performed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months and evaluated by a central reader blinded to treatment. A pituitary tumor volume change of ≥20% from screening was considered significant. Tumor volume was calculated by hand-drawing around the tumor circumference in coronal cross-sections, multiplying the area by slice thickness, and summing the resulting volumes across all slices containing tumor. For further details, see the Supplemental Appendix (published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online website at http://jcem.endojournals.org).

Safety was assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (CTC) for Adverse Events version 3.0 (12) and consisted of monitoring and recording of all adverse events (AEs); regular monitoring of hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis parameters; performance of physical examinations; and body weight measurements. Blood samples for laboratory tests, including blood glucose measurements, were drawn at each visit under fasted conditions before the morning dose.

Changes in diabetic category during treatment with pasireotide LAR or octreotide LAR were determined using the American Diabetes Association (13) definitions for diabetic category.

Hormone assays

Serum GH and IGF-1 were measured using validated chemiluminescent immunometric assays (Immulite 2000/1000; Diagnostic Products Corp [Siemens]; GH International Reference Preparation World Health Organization National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls second IS 98/574; IGF-1 International Reference Preparation World Health Organization National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls first IRR 87/518). The lower limit of detection for GH was 0.1 μg/L, with intra- and interassay coefficients of variation ≤6.6%. For IGF-1, the lower limit of detection was 20 μg/L, with intra- and interassay coefficients of variation ≤6.7%. IGF-1 values were compared with age- and sex-standardized normal values. All samples except for those from China were analyzed by Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute Laboratory between March 2008 and March 2010 and then by Quest Diagnostics Clinical Trials Laboratory from March 2010 onward. Samples from China were analyzed by Kingmed Diagnostics. Subsequent to receiving a notification from Siemens regarding the Immulite IGF-1 assay, Quest Diagnostics reviewed all quality control data collected during this clinical trial and verified that all IGF-1 data are valid. See the Supplemental Appendix for further details.

Statistical analyses

The primary and secondary efficacy results were based on the intent-to-treat population. The principle of last observation carried forward (LOCF) was included in the study protocol as an amendment while the study was ongoing to fully use the response data in patients who discontinued before month 12 but had been enrolled in the study for at least 6 months. LOCF was applied to the endpoints of biochemical response; ie, if the month-12 mean GH or IGF-1 value was missing, it was imputed by the last available value between months 6 and 12 (including month 6). If there were no available values between months 6 and 12 (including months 6 and 12), patients were considered nonresponders.

The null hypothesis was that there would be no difference between the 2 treatments in the proportion of patients achieving GH <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 at month 12. The alternative hypothesis was that the response rates would be different. It was assumed that 75% and 25% of patients would enroll in the postsurgical and de novo strata, respectively. A sample size of at least 330 patients was needed to detect a 15% increase in response rate from 20% in the octreotide LAR group to 35% in the pasireotide LAR group, based on a 2-sided Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test at the .05 level with 80% power and allowing for a 9% patient dropout rate.

A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusting for randomization stratum was used for the primary and key efficacy analyses. The analysis of covariance model used for the change in tumor volume at month 12 includes treatment and randomization stratification factor as the fixed effect and baseline tumor volume as a covariate.

Safety data were analyzed based on the safety population according to the first treatment received.

Post hoc analyses included the proportion of patients achieving GH <2.5 μg/L and IGF-1 at or below the ULN (patients with IGF-1 below the lower normal limit were not considered as responders in the primary efficacy analyses) and the difference in the incidence of hyperglycemia-related AEs between the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR treatment arms.

Results

In total, 546 patients were screened and 358 patients were randomized to pasireotide LAR (n = 176) or octreotide LAR (n = 182). Two patients randomized to octreotide LAR received pasireotide LAR in error.

The 2 treatment groups were similar in terms of baseline demographics and disease characteristics; 58% of patients were de novo (Table 1). Baseline mean GH was 21.9 and 18.8 μg/L, baseline mean standardized IGF-1 was 3.1 and 3.1 times ULN, and baseline mean tumor volume was 2421 and 2259 mm3 in the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

| Demographic Variable | Pasireotide LAR, n = 176 | Octreotide LAR, n = 182 | All Patients, n = 358 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median (range), y | 46 (18–80) | 45 (19–85) | 46 (18–85) |

| ≥65 y, n (%) | 8 (4.5) | 15 (8.2) | 23 (6.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 85 (48.3) | 87 (47.8) | 172 (48.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 105 (59.7) | 111 (61.0) | 216 (60.3) |

| Black | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 7 (2.0) |

| Asian | 39 (22.2) | 43 (23.6) | 82 (22.9) |

| Native American | 6 (3.4) | 5 (2.7) | 11 (3.1) |

| Other | 23 (13.1) | 19 (10.4) | 42 (11.7) |

| Median time since diagnosis (range), mo | 5.6 (0.4–357.5) | 6.4 (0.4–377.1) | 6.0 (0.4–377.1) |

| Previous surgery, n (%) | 71 (40.3) | 80 (44.0) | 151 (42.2) |

| Median time since surgery (range), mo | 9.5 (1.6–328.8) | 6.2 (1.2–377.1) | 7.0 (1.2–377.1) |

| Previous radiation, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

Overall, 80.1% and 85.7% of pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients completed 12 months of treatment; median drug exposure was 336 days in both groups. The most frequent reasons for discontinuation among pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients, respectively, were AEs (8.0% and 3.3%) and protocol deviation (4.0% and 4.4%).

Primary and related endpoints

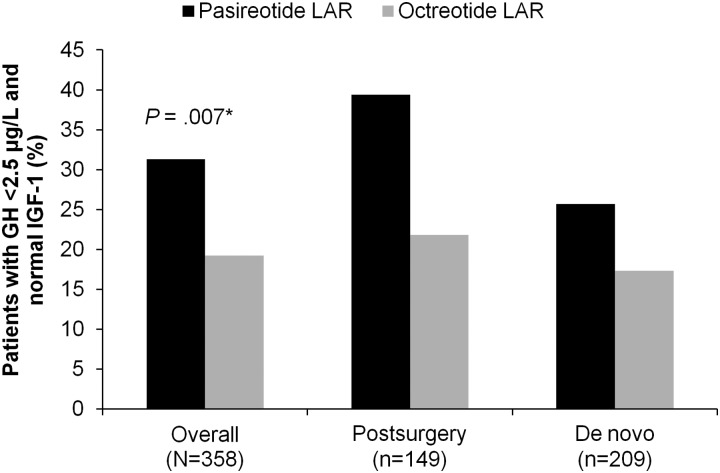

Significantly more pasireotide LAR patients achieved biochemical control at month 12 than octreotide LAR patients (31.3% vs 19.2%; P = .007; Figure 1 and Table 2), with pasireotide LAR patients being 63% more likely to achieve biochemical control than octreotide LAR patients. The odds ratio (OR) for achieving the primary endpoint, adjusted for randomization strata, was 1.94 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–3.17) favoring pasireotide LAR.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients in the overall population, postsurgery stratum and de novo stratum with GH <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 after 12 months of treatment with pasireotide LAR or octreotide LAR. *, P = .007 pasireotide LAR vs octreotide LAR in the overall population. The study was not powered to detect treatment differences in subgroups. The 95% CI of the OR in favor of pasireotide LAR reached statistical significance at the .05 level for postsurgery patients (OR, 2.34 [95% CI, 1.14–4.79]) but not de novo patients (OR, 1.65 [95% CI, 0.85–3.23]).

Table 2.

Proportion of Patients at Month 12 With GH <2.5 μg/L and Normal IGF-1, GH <2.5 μg/L, and Normal IGF-1, by Stratum and Treatmenta

| Pasireotide LAR,b % (n/N) (95% CI) | Octreotide LAR,b % (n/N) (95% CI) | Between Treatments |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| n | 176 | 182 | ||

| GH <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 at month 12 (LOCF) | ||||

| Overall | 31.3 (55/176) (24.5–38.7) | 19.2 (35/182) (13.8–25.7) | 1.94 (1.19–3.17) | .007 |

| After surgery | 39.4 (28/71) (28.0–51.7) | 21.8 (17/78) (13.2–32.6) | 2.34 (1.14–4.79) | |

| De novo | 25.7 (27/105) (17.7–35.2) | 17.3 (18/104) (10.6–26.0) | 1.65 (0.85–3.23) | |

| GH <2.5 μg/L at month 12 (LOCF) | ||||

| Overall | 48.3 (85/176) (40.7–55.9) | 51.6 (94/182) (44.1–59.1) | 0.88 (0.58–1.33) | .54 |

| After surgery | 52.1 (37/71) (39.9–64.1) | 51.3 (40/78) (39.7–62.8) | 1.03 (0.54–1.97) | |

| De novo | 45.7 (48/105) (36.0–55.7) | 51.9 (54/104) (41.9–61.8) | 0.78 (0.45–1.34) | |

| Normal IGF-1 at month 12 (LOCF) | ||||

| Overall | 38.6 (68/176) (31.4–46.3) | 23.6 (43/182) (17.7–30.5) | 2.09 (1.32–3.31) | .002 |

| After surgery | 50.7 (36/71) (38.6–62.8) | 26.9 (21/78) (17.5–38.2) | 2.79 (1.41–5.53) | |

| De novo | 30.5 (32/105) (21.9–40.2) | 21.2 (22/104) (13.8–30.3) | 1.63 (0.87–3.06) | |

| GH <2.5 μg/L and IGF-1 below the upper normal limit at month 12 (LOCF) | ||||

| Overall | 35.8 (63/176) | 20.9 (38/182) | ||

| After surgery | 45.1 (32/71) | 25.6 (20/78) | ||

| De novo | 29.5 (31/105) | 17.3 (18/104) | ||

After surgery indicates patients who were medical treatment-naive after surgery; de novo indicates treatment-naïve. P values are based on a 2-sided Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for randomization stratification factor.

Dose up-titration was recommended but performed at the discretion of the investigator.

Biochemical control was achieved by 39.4% of pasireotide LAR patients vs 21.8% of octreotide LAR patients in the postsurgical stratum (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.14–4.79) and by 25.7% of pasireotide LAR patients vs 17.3% of octreotide LAR patients in the de novo stratum (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.85–3.23).

Including 8 pasireotide LAR patients (4 in the postsurgical stratum) and 3 octreotide LAR patients (all in the postsurgical stratum) who had IGF-1 below the lower normal limit and GH <2.5 μg/L, 35.8% (63 of 176) of pasireotide LAR patients and 20.9% (38 of 182) of octreotide LAR patients achieved GH <2.5 μg/L and IGF-1 levels at or below the ULN (Table 2).

At month 12 in the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR groups, respectively, IGF-1 was normalized in 38.6% and 23.6% of patients (P = .002) and GH <2.5 μg/L was achieved by 48.3% and 51.6% of patients (P = .54). Normal IGF-1 was achieved in 50.7% vs 26.9% of postsurgery and 30.5% vs 21.2% of de novo pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients. Control of GH was seen in a similar proportion of postsurgery and de novo patients with both treatments (Table 2).

For the primary analyses, the last value of GH and IGF-1 obtained between months 6 and 12 (including month 6) was carried forward for patients who did not have GH and IGF-1 values at month 12. Of the 39 pasireotide LAR patients and 31 octreotide LAR patients who did not have GH and IGF-1 values at month 12, 20 and 21 had their LOCF, and 4 and 3, respectively, were counted as responders. If these 7 patients were considered nonresponders, biochemical control was achieved by 29.0% of pasireotide LAR patients vs 17.6% of octreotide LAR patients (P = .009).

During the 12 months of treatment, 50.6% of pasireotide LAR patients and 67.6% of octreotide LAR patients received dose up-titration. Of the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients who did not achieve GH <2.5 μg/L or IGF-1 at or below ULN, 35 of 113 patients (31.0%) and 32 of 144 patients (22.2%) did not receive a dose increase. Eleven of the 63 (17.5%) pasireotide LAR and 11 of the 38 (28.9%) octreotide LAR patients who achieved GH <2.5 μg/L or IGF-1 at or below ULN received a dose increase during the 12 months.

Other secondary efficacy endpoints

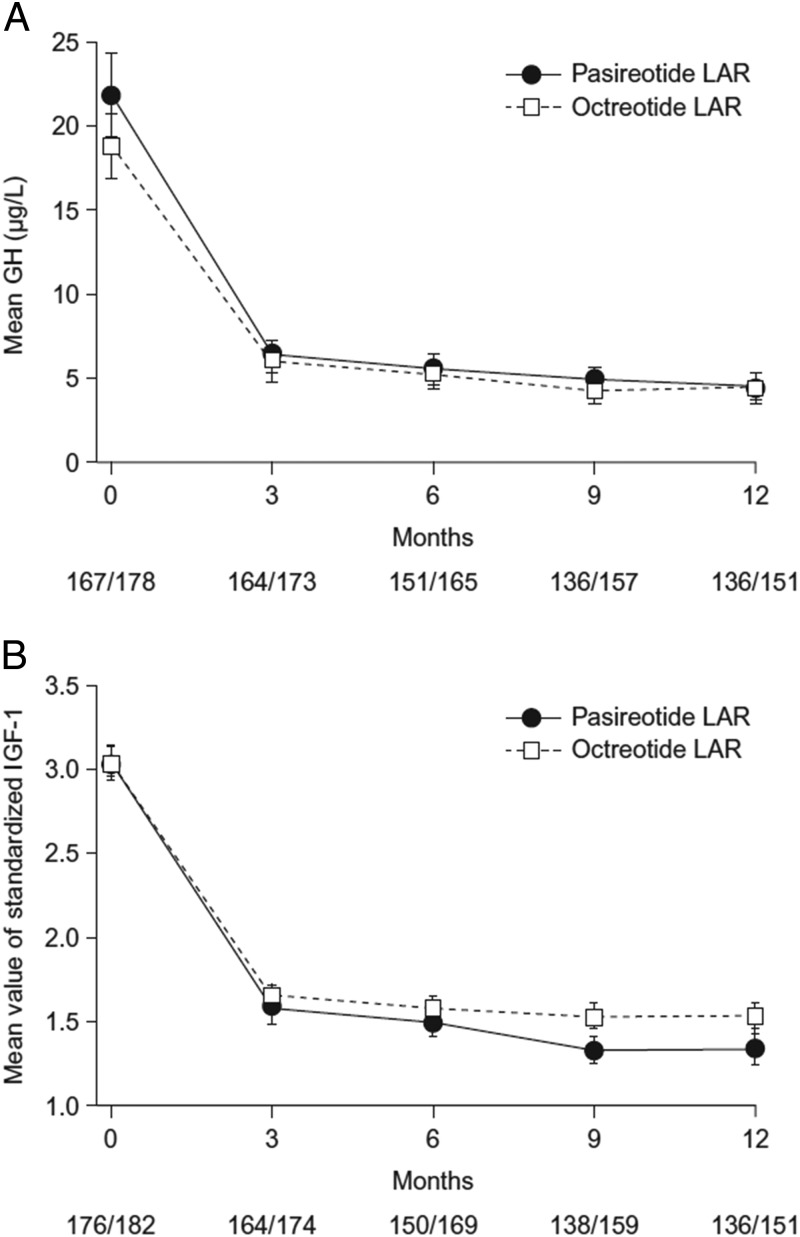

Mean GH and IGF-1 levels decreased rapidly within the first 3 months and remained low in both treatment arms (Figure 2). At month 3, 30.1% and 21.4% of pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients had biochemical control.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SE GH levels (A) and standardized IGF-1 levels (B) over time by treatment group. The numbers at the bottom of each graph are the numbers of patients in the pasireotide LAR/octreotide LAR treatment groups. Standardized IGF-1 is the IGF-1 value divided by the ULN range.

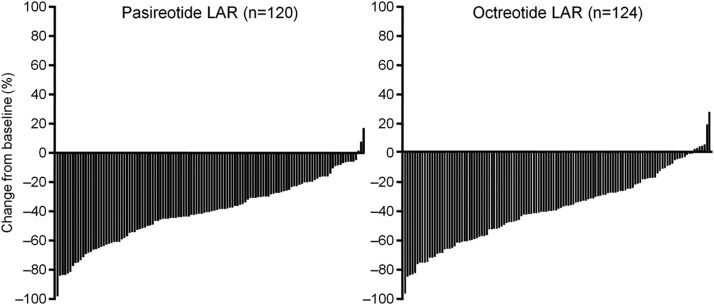

From baseline to month 12, mean tumor volume decreased by 40% and 38% in the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR groups, respectively (P = .838). A significant (≥20%) tumor volume reduction was achieved by 80.8% and 77.4% of pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients; 1 patient experienced a ≥20% increase in tumor volume in the octreotide LAR arm (Figure 3). A similar magnitude of tumor volume reduction was observed in the postsurgery and de novo groups.

Figure 3.

Percent change in tumor volume from baseline to month 12 in patients with baseline and month-12 MRI assessments.

Both agents were effective at improving the symptoms of acromegaly and QoL. At baseline, mean AcroQoL scores were 58.4 (SD, 20.0) in patients receiving pasireotide LAR and 55.6 (SD, 19.8) in patients receiving octreotide LAR. At month 12, improvement in QoL was seen in both treatment groups. AcroQoL scores had improved by a mean of 7.0 points (SD, 14.5) in the pasireotide LAR arm and by a mean of 4.9 points (SD, 15.5) in the octreotide LAR arm. The severity of individual symptoms at baseline was similar for both treatment arms, with symptom scores between 0.7 and 1.4. Improvements in all 5 symptoms were seen by month 12. In both treatment arms (pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR), the largest improvement was in perspiration (mean, −0.6 [SD, 1.14] and −0.8 [SD, 1.20]). Similar improvements were seen in fatigue (mean, −0.4 [SD, 1.18] and −0.6 [SD, 0.96]), osteoarthralgia (mean, −0.4 [SD, 1.07] and −0.6 [SD, 1.20]), paresthesia (mean, −0.4 [SD, 0.90] and −0.4 [SD, 1.11]), and headache (mean, −0.3 [SD, 1.17] and −0.4 [SD, 0.94]).

Safety and tolerability

The most common AEs (all CTC grades) with pasireotide LAR vs octreotide LAR (Table 3) were mostly mild-to-moderate diarrhea (39.3% vs 45.0%), cholelithiasis (25.8% vs 35.6%), headache (18.5% vs 25.6%), and hyperglycemia (28.7% vs 8.3%).

Table 3.

Adverse Events Regardless of Study-Drug Relationship Reported in ≥10% of Patients in Either Treatment Group

| Pasireotide LAR, n = 178a |

Octreotide LAR, n = 180a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Grades, n (%) | Grade 3/4, n (%) | All Grades, n (%) | Grade 3/4, n (%) | |

| Diarrhea | 70 (39.3) | 1 (0.6) | 81 (45.0) | 4 (2.2) |

| Hyperglycemia | 51 (28.7) | 6 (3.4) | 15 (8.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Cholelithiasis | 46 (25.8) | 1 (0.6) | 64 (35.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (19.1) | 9 (5.1) | 7 (3.9) | 0 |

| Headache | 33 (18.5) | 2 (1.1) | 46 (25.6) | 5 (2.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 32 (18.0) | 1 (0.6) | 40 (22.2) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 32 (18.0) | 0 | 35 (19.4) | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 28 (15.7) | 0 | 28 (15.6) | 0 |

| Nausea | 24 (13.5) | 1 (0.6) | 39 (21.7) | 0 |

| Increased blood creatine phosphokinase | 23 (12.9) | 3 (1.7) | 21 (11.7) | 4 (2.2) |

| Abdominal distension | 21 (11.8) | 1 (0.6) | 21 (11.7) | 1 (0.6) |

| Arthralgia | 17 (9.6) | 1 (0.6) | 22 (12.2) | 1 (0.6) |

| Fatigue | 17 (9.6) | 1 (0.6) | 18 (10.0) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 17 (9.6) | 0 | 19 (10.6) | 0 |

| Back pain | 14 (7.9) | 0 | 20 (11.1) | 2 (1.1) |

Two patients randomized to the octreotide LAR treatment arm received pasireotide LAR in error. These 2 patients are included in the pasireotide LAR treatment arm for the purposes of the safety analysis.

When common AE terms were grouped, for example, all terms relating to elevations in blood glucose or terms relating to diarrhea, the most common AEs in the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR groups were hyperglycemia-related (57.3% [95% CI, 49.7%–64.7%] and 21.7% [95% CI, 15.9%–28.4%]), diarrhea-related (39.3% [95% CI, 32.1%–46.9%] and 45.0% [95% CI, 37.6%–52.6%), and gallbladder- and biliary-related (30.9% [95% CI, 24.2%–38.3%] and 38.9% [95% CI, 31.7%–46.4%]). Post hoc analysis showed that the difference in the incidence of hyperglycemia-related AEs between the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR treatment arms was 35.6% (95% CI, 25.5%–44.9%).

Fourteen (8.0%) pasireotide LAR and 6 (3.3%) octreotide LAR patients discontinued because of an AE during the 12-month treatment period. The most common AEs leading to discontinuation in the pasireotide LAR group were related to elevations in blood glucose (3 because of diabetes mellitus, 2 because of hyperglycemia, and 1 because of increased HbA1c). A CTC grade 3 or 4 hyperglycemia-related AE was reported by 9.0% of pasireotide LAR patients and 1.7% of octreotide LAR patients. At least 1 serious AE was experienced by 12.9% and 10.6% of pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients, and 4.5% and 2.8% of patients experienced 1 or more serious AEs considered to be study drug-related. Eight patients (4.5%) discontinued treatment because of a serious AE, all in the pasireotide LAR arm. One patient in the octreotide LAR group died of a myocardial infarction, but this was not considered study drug-related.

In patients treated with pasireotide LAR or octreotide LAR, respectively, mean (SD) increases in HbA1c from baseline to the last available value within 12 months by baseline diabetic status were: 0.87% (1.32%) and 0.03% (0.78%) in diabetic patients, 0.64% (0.78%) and 0.11% (0.35%) in prediabetic patients, and 0.75% (0.58%) and 0.37% (0.46%) in patients with normal glucose tolerance at baseline.

The mean time to the first report of a glucose abnormality was 84 days for pasireotide LAR and 196 days for octreotide LAR. The mean time to first antidiabetic medication was 123 and 212 days in the pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR arms, respectively. Antidiabetic medication was received by 44.4% and 26.1% of pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR patients. Metformin and sulfonylureas were most commonly used.

Discussion

This is the largest randomized, active-comparator–controlled trial in patients with acromegaly. It is also one of the few studies to enroll patients naive to medical therapy and to strictly report biochemical control using the criteria of both GH <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 for age and sex. Pasireotide LAR provided strong suppression of IGF-1, and patients were 63% more likely to achieve biochemical control with pasireotide LAR. The proportion of patients with biochemical control was higher with pasireotide LAR than with octreotide LAR in both the de novo and postsurgical strata.

In 2010, the Acromegaly Consensus Group indicated that a random GH level of <1.0 μg/L, using an ultrasensitive GH assay, and normal IGF-1 for age and sex indicates controlled disease (14). Earlier studies measuring GH by RIA suggested that a random GH level of <2.5 μg/L and normal IGF-1 for age and sex is associated with normal life expectancy (2). The protocol for the current study was finalized in 2007. At that time, acromegaly management guidelines recommended a target GH level of 2.5 μg/L (15), so the target GH level in this study was 2.5 μg/L. Nonetheless, current guidelines should be adhered to in clinical practice, with an on-treatment target GH level of <1.0 μg/L.

With respect to hormone secretion, it is of interest that pasireotide LAR was significantly more effective than octreotide LAR at inhibiting IGF-1 but that the 2 drugs had a similar effect on GH inhibition. This superior effect on IGF-1 by pasireotide is important, because most of the effects of GH are mediated by IGF-1. It has been postulated that somatostatin analogs may act on both the pituitary and on peripheral target tissues of GH to reduce GH-induced IGF-1 production (16) and that the nonpituitary action of somatostatin analogs on the GH/IGF-1 axis may be due to antagonism of the action of GH on hepatic IGF-1 as well as insulin suppression (17). The fact that pasireotide was more effective than octreotide at suppressing IGF-1 in the current study may be due to the higher affinity and functional activity of pasireotide at hepatic sst1, sst3, or sst5 receptors.

An unexpectedly large number of de novo patients were enrolled in the trial; 58% of patients were de novo and 42% were postsurgical. The GH and IGF-1 inclusion criteria for the study were GH >1 μg/L after an OGTT or a 5-point mean serum GH >5 μg/L and IGF-1 above the ULN for age- and sex-matched controls. The serum GH entry criterion is considered high and may have caused a more difficult-to-treat patient population to be enrolled. For example, GH and IGF-1 levels are often higher in patients with newly diagnosed acromegaly than in patients with active acromegaly who have undergone previous surgery (18).

Nonetheless, the octreotide LAR response rate for biochemical control in the present study (19.2%) is consistent with recent prospective studies of octreotide LAR in patients with de novo acromegaly, where results from the intention-to-treat population were reported after 1 year of treatment. In 2 recent studies of octreotide LAR in patients with de novo acromegaly, biochemical control was achieved in 17% and 27% of the intent-to-treat population after 48 weeks treatment with octreotide LAR as first-line therapy (5, 7). Indeed, it was on the basis of these results (5, 7) that the current study was designed with an expected response rate of 20% for octreotide LAR. Similar results have been seen in medically naive patients with acromegaly treated with lanreotide Autogel in a recent international prospective clinical trial (6). Early open-label studies of octreotide LAR as second-line therapy reported GH and IGF-1 response rates of 55% to 70% and 64% to 66%, respectively (19–21). However, a composite endpoint of GH and IGF-1 control was not reported in these studies, in which the rate of control was evaluated by summing the number of patients with either GH <2.5 μg/L or normal IGF-1, and patients were preselected for responsiveness to octreotide.

Studies with conventional somatostatin analogs have shown that higher response rates can be achieved when the somatostatin analog dose is increased and dose titration is rigorously performed (22). The study protocol permitted dose up-titration at month 3 or 7 if patients were not biochemically controlled. However, the decision to up-titrate was left to the discretion of the investigator; 31.0% of pasireotide LAR and 22.2% of octreotide LAR patients who did not achieve biochemical control did not receive the recommended dose increase. Although it is of some concern that these patients were not dose up-titrated, the reasons for not increasing the dose were not collected. As such, the response rates for both pasireotide LAR and octreotide LAR might have been higher had these patients received the recommended dose increase.

The doses of pasireotide LAR used in this study were selected based on pharmacokinetic data from earlier studies of pasireotide in patients with acromegaly (9, 23, 24). A study in 35 patients with acromegaly showed that the trough concentrations of pasireotide at steady state (28 days after the third injection) were 3.8 ± 2.1, 6.4 ± 3.1, and 13.7 ± 9.6 ng/mL after 3 monthly injections of pasireotide LAR 20, 40, and 60 mg, respectively (23). The trough concentrations after the 40- and 60-mg doses, but not the 20-mg dose, were above the median value of effective concentration required for GH normalization in responders to pasireotide sc treatment, based on data from a 3-month study of pasireotide 200, 400, and 600 μg sc bid (twice per day) in patients with acromegaly (24, 25). Therefore, pasireotide LAR 40 mg was chosen as the starting dose for the current study. The starting dose of octreotide LAR was based on the recommended posology in the Sandostatin LAR label.

The most common AEs in both groups were gastrointestinal, as expected with somatostatin analogs, and occurred early in the course of treatment. Hyperglycemia-related AEs were more frequently reported in the pasireotide LAR group. This suggests that in patients who develop hyperglycemia that cannot be controlled, the benefits of pasireotide LAR with respect to biochemical control may be offset. However, no specific guidance on how to manage hyperglycemia was given in the study protocol. At the time of study initiation, the mechanism behind the increase in glucose levels during pasireotide LAR treatment was unknown and it was recommended in the study protocol that current American and European diabetes mellitus guidelines should be followed. Subsequently, 2 studies in healthy volunteers showed that pasireotide inhibited insulin secretion and incretin response, with minimal inhibition of glucagon secretion and no impact on insulin sensitivity, and that dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists were effective at ameliorating pasireotide-induced hyperglycemia (26, 27). Blood glucose levels should be closely monitored in patients treated with pasireotide, and treatment should be promptly initiated if blood glucose levels increase according to established guidelines until the most effective way to prevent or control increases in blood glucose has been confirmed in further studies.

This study confirms that pasireotide LAR achieves greater suppression of IGF-1 than octreotide LAR and is significantly superior to octreotide LAR at providing biochemical control. The safety profile of pasireotide LAR was as expected for a somatostatin analog, except for the degree of hyperglycemia. In conclusion, pasireotide LAR demonstrated superior efficacy over octreotide LAR and is a viable new treatment option for acromegaly.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the investigators who contributed to the study, the study nurses and coordinators, and the patients who participated in the study. Members of the Pasireotide C2305 Study Group include G. Akcay, A. Arafat, S. Arellano, A. Barkan, J. Bertherat, M. Bex, C. Boguszewski, J. Bollerslev, F. Borson-Chazot, M. Bronstein, T. Brue, O. Bruno, F. Casanueva, C.-N. Chang, T.-C. Chang, P. Chanson, A. Chervin, C. Chik, A. Colao, B. Corvilain, L. De Marinis, E. Degli Uberti, L. Duan, B. Edén Engstrom, T. Erbas, A. J. Farrall, M. Faria, M. Fleseriu, P. Freda, M. Gadelha, E. Ghigo, B. Glaser, M. Gordon, E. Grineva, F. Gu, M. Guitelman, A. Heaney, G. Houde, L. Katznelson, Y. Khalimov, K.-W. Kim, M.-S. Kim, S.-W. Kim, P. Laurberg, E.-J. Lee, W. Ludlam, J. Marek, E. Martino, M. McPhaul, M. Mercado, F. Minuto, R. Montenegro, L. Naves, G. Ning, G. Piaditis, A. Pico Alfonso, V. Pronin, S. Quinn, K. Racz, W. Rojas, L. Rozhinskaya, R. Salvatori, S. Samson, D. Sandeman, J. Schopohl, O. Serri, C.-C. Shen, M. Sheppard, I. Shimon, J. Soler Ramon, A. Tabarin, G. T'Sjoen, N. Unger, A. J. van der Lely, E. Venegas Moreno, S. Waguespack, and W. Zgliczyński. We also acknowledge the following from Novartis Pharmaceuticals for their contributions to this study: Nicolas Flores, Patricia Nies-Berger, and Katja Roessner. We thank Keri Wellington, PhD, for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Disclosure Summary: F.G. and C.-C.S. have nothing to declare. M.D.B. has received consulting fees from Chiasma, Ipsen, and Novartis; speaker fees from Ipsen and Novartis; and research grants from Ipsen and Novartis. A.J.F. has received consulting fees from Novartis. M.G. has received grant support from Novartis and Pfizer and speaker fees from Novartis, Ipsen, and Pfizer; has served on advisory boards for Novartis; and is principal investigator of Novartis clinical trials. M.S. has received lecture fees from Novartis. A.C. has received unrestricted grants and lecture fees from Novartis and has served on advisory boards for Novartis. P.F. has received research grant support from and has served on advisory boards for Novartis, Pfizer, and Ipsen. M.F. is a principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis and Ipsen with research support to Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU). M.F. has received payments for consulting for Novartis and Ipsen. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU. A.J.v.d.L. has received financial support for investigator-initiated research and unrestricted grants from Novartis, Pfizer and Ipsen. Y.C., K.H.R., and M.R. are employed by Novartis.

Footnotes

- AE

- adverse event

- CI

- confidence interval

- CTC

- Common Terminology Criteria

- HbA1c

- glycated hemoglobin

- HRQoL

- health-related quality of life

- LAR

- long-acting-release

- LOCF

- last observation carried forward

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- OR

- odds ratio

- sst

- somatostatin receptor subtype

- ULN

- upper limit of normal.

References

- 1. Arosio M, Reimondo G, Malchiodi E, et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in acromegaly: an Italian survey. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holdaway IM, Bolland MJ, Gamble GD. A meta-analysis of the effect of lowering serum levels of GH and IGF-I on mortality in acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nomikos P, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R. The outcome of surgery in 668 patients with acromegaly using current criteria of biochemical ‘cure’. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:379–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grasso LF, Pivonello R, Colao A. Somatostatin analogs as a first-line treatment in acromegaly: when is it appropriate? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19:288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colao A, Cappabianca P, Caron P, et al. Octreotide LAR vs. surgery in newly diagnosed patients with acromegaly: a randomized, open-label, multicentre study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2009;70:757–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Melmed S, Cook D, Schopohl J, Goth MI, Lam KS, Marek J. Rapid and sustained reduction of serum growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 in patients with acromegaly receiving lanreotide Autogel therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study with a 52 week open extension. Pituitary. 2010;13:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mercado M, Borges F, Bouterfa H, et al. A prospective, multicentre study to investigate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of octreotide LAR (long-acting repeatable octreotide) in the primary therapy of patients with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66:859–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruns C, Lewis I, Briner U, Meno-Tetang G, Weckbecker G. SOM230: a novel somatostatin peptidomimetic with broad somatotropin release inhibiting factor (SRIF) receptor binding and a unique antisecretory profile. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petersenn S, Schopohl J, Barkan A, et al. Pasireotide (SOM230) demonstrates efficacy and safety in patients with acromegaly: a randomized, multicenter, Phase II trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2781–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dietrich H, Hu K, Ruffin M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of a single dose of pasireotide long-acting release in healthy volunteers: a single-center Phase I study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:821–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Webb SM, Prieto L, Badia X, et al. Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (ACROQOL) a new health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with acromegaly: development and psychometric properties. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;57:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). National Cancer Institute website; http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf Accessed May 21, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus 2010. Diabetes Care. 33(Suppl 1):S62–S69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giustina A, Chanson P, Bronstein MD, et al. A consensus on criteria for cure of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3141–3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melmed S, Colao A, Barkan A, et al. Guidelines for acromegaly management: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1509–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murray RD, Kim K, Ren SG, Chelly M, Umehara Y, Melmed S. Central and peripheral actions of somatostatin on the growth hormone-IGF-I axis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pokrajac A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Trainer PJ. Pituitary-independent effect of octreotide on IGF1 generation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cozzi R, Attanasio R, Montini M, et al. Four-year treatment with octreotide-long-acting repeatable in 110 acromegalic patients: predictive value of short-term results? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3090–3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fløgstad AK, Halse J, Bakke S, et al. Sandostatin LAR in acromegalic patients: long-term treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lancranjan I, Bruns C, Grass P, et al. Sandostatin LAR: a promising therapeutic tool in the management of acromegalic patients. Metabolism. 1996;45:67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lancranjan I, Atkinson AB. Results of a European multicentre study with Sandostatin LAR in acromegalic patients. Sandostatin LAR Group. Pituitary. 1999;1:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleseriu M. Clinical efficacy and safety results for dose escalation of somatostatin receptor ligands in patients with acromegaly: a literature review. Pituitary. 2011;14:184–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petersenn S, Bollerslev J, Arafat AM, et al. Pasireotide LAR shows efficacy in patients with acromegaly: interim results from a randomized, multicenter, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, Phase I study. In: Program of the 90th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society; June 15–18, 2008; San Francisco, CA Abstract OR41-5 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu K, Zhang Y, Jung J, Buchelt A, Wang Y, Petersenn S. Pasireotide (SOM230) provides biochemical control in patients with active acromegaly: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) results from a randomized, multicenter, Phase II trial. In: Program of the 91st Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society; June 10–13, 2009; Washington, DC Abstract P3-677 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersenn S, Unger N, Hu K, et al. Pasireotide (SOM230), a novel multireceptor-targeted somatostatin analogue, is well tolerated when administered as a continuous 7-day subcutaneous infusion in healthy male volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henry RR, Ciaraldi TP, Armstrong D, Burke P, Ligueros-Saylan M, Mudaliar S. Hyperglycemia associated with pasireotide: results from a mechanistic study in healthy volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3446–3453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breitschaft A, Hu K, Hermosillo Reséndiz K, Darstein C, Golor G. Management of hyperglycemia associated with pasireotide (SOM230): healthy volunteer study [published online December 25, 2013]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]