ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Recent and national data on adherence to heart failure drugs are limited, particularly among the disabled and some small minority groups, such as Native Americans and Hispanics.

OBJECTIVE

We compare medication adherence among Medicare patients with heart failure, by disability status, race/ethnicity, and income.

DESIGN

Observational study.

SETTING

US Medicare Parts A, B, and D data, 5 % random sample, 2007–2009.

PARTICIPANTS

149,893 elderly Medicare beneficiaries and 21,204 disabled non-elderly beneficiaries.

MAIN MEASURES

We examined 5 % of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with heart failure in 2007–2009. The main outcome was 1-year adherence to one of three therapeutic classes: β-blockers, diuretics, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). Adherence was defined as having prescriptions in possession for ≥ 75 % of days.

KEY RESULTS

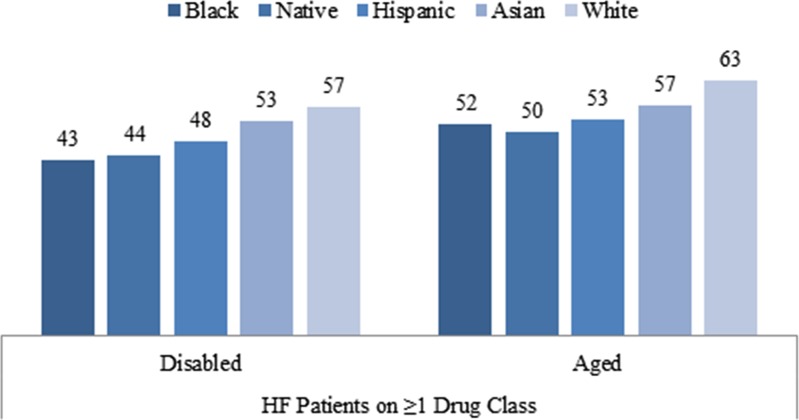

Among aged beneficiaries, 1-year adherences to at least one heart failure drug were 63 %, 57 %, 53 %, 50 %, and 52 % for Whites, Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans and Blacks, respectively; among the disabled, 1-year adherence was worse for each group: 57 %, 53 %, 48 %, 44 % and 43 % respectively. The racial/ethnic difference persisted after adjustment for age, gender, income, drug coverage, location and health status. Patterns of adherence were similar among beneficiaries on all three therapeutic classes. Among beneficiaries with close-to-full drug coverage, minorities were still less likely to adhere relative to Whites, OR = 0.61 (95 % CI 0.58–0.64) for Hispanics, OR = 0.59 (95 % CI 0.57–0.62) for Blacks and OR = 0.57 (95 % CI 0.47–0.68) for Native Americans.

CONCLUSION

After the implementation of Medicare Part D, adherence to heart failure drugs remains problematic, especially among disabled and minority beneficiaries, including Native Americans, Blacks, and Hispanics. Even among those with close-to-full drug coverage, racial differences remain, suggesting that policies simply relying on cost reduction cannot eliminate racial differences.

KEY WORDS: racial disparity, Medicare, heart failure, medication adherence, disability

Heart failure (HF) affects more than 5 million Medicare beneficiaries, and is the most important reason for hospitalizations in the elderly.1 Clinical guidelines recommend that, absent contraindications, patients with HF take a β-blocker, and an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor antagonist (ARB), or sometimes a diuretic.2 These medications are very effective, and have been shown to save lives and downstream costs.3,4 However, the consistent use of these agents by patients with heart diseases is suboptimal by many measures. In 2002, only 46 % of patients with heart disease consistently used β-blockers, and only 44 % used lipid-lowering therapy.5 A recent trial demonstrated that rates of adherence were alarmingly low for patients in a large commercial insurer with a recent event of myocardial infarction: 35.9 % for ACEIs or ARBs, 45.0 % for β-blockers, 49.0 % for statins, and 38.9 % for all three medication classes.6 Medication adherence in heart failure is no better:7 a recent study found that the average rate of good adherence was only 52 % for Medicare patients with heart failure in 2007–2009 national Medicare Part D data.8

Adherence may be especially important for Medicare beneficiaries, who often have multiple conditions and use an average of four drugs per month.9 After the implementation of Medicare Part D, medication adherence to heart failure drugs has improved.10 It is important to assess racial difference in overall nonadherence to heart failure drugs using newer, large scale national Part D data. Part D program offers a generous federal subsidy to individuals below 150 % of federal poverty line. Because high drug cost is one of the main factors explaining the racial difference in adherence, it is important to assess whether racial disparity in adherence persists among those who pay little copayments for drugs. Previous data on racial disparity in adherence to heart failure drugs by racial groups have been primarily limited to comparing African American and Whites. It is important to study the difference between Whites and other minority groups, including Hispanic, Asians, and Native Americans.

To answer these important questions, we use a 5 % random sample of Medicare Part D data from 2007 to 2009 to examine 1-year medication adherence to heart failure drugs among patients with heart failure. We compare adherence among Whites, non-White Hispanics, Asians, African Americans, and Native Americans, stratified by their disability status and their low-income subsidy status. We separately examine racial difference for the elderly and the disabled Medicare beneficiaries, because their disease and treatment patterns are quite different, and the racial difference in the disabled may be quite different from the difference in the elderly.

METHODS

Study Population

We obtained 2006–2009 enrollment, drug event and medical claims data for a 5 % random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. We identified beneficiaries aged ≥ 18 and having at least one inpatient or two (non-laboratory) outpatient claims between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2009 with selected ICD9 codes indicating HF on primary, secondary and third diagnosis (Appendix Table 4).8,11 The first claim for HF diagnosis was defined as the diagnosis index date. Guided by the clinical guidelines,2 we selected β-blockers, ACEI/ARB, and diuretics as our medications of interest. We identified the first prescription drug of interest filled after the diagnosis index date (drug index date), and followed patients from the drug index date for 1 year, or until the end of the study period (31 December 2009) or death (n = 184,028). We further constrained our sample to those continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B and D insurance coverage during the follow-up period (n = 178,102; or 96.8 %). Of this study sample, 66.41 % (n = 118,276) had 1-year follow-up, 15.76 % (n = 28,066) died and 17.83 % (n = 31,760) did not die, but had less than 1-year follow-up. [We tested the sensitivity analysis only for those with full-year enrollees, and the results are quantitatively similar. For the purpose of generalizability, we report the results including those with partial-year enrollees.]

Table 4.

Definition for Heart Failure

| Chronic conditions | Reference time period | Valid ICD-9 codes | Number/type of claims to qualify |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | 1 January 2006–31 December 2009 | DX: 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.03, 404.13, 404.93, 428.0X-428.4X, 428.9X (any DX on the claim) | At least one inpatient, outpatient or physician claim with DX codes during the 4-year period (2006–2009) |

The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. The data were obtained through funding from the Institute of Medicine and the National Institute of Health, and the study analyses were funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The sponsors played no role in the study conduct, data analysis, or report generation.

Outcomes

We first measured medication possession ratio (MPR), the proportion of days in a given study period that a subject had possession of a drug of study interest. We then defined an indicator for good adherence (1 = MPR ≥ 0.75; 0 = otherwise), a commonly used threshold.6,10 Patients in our study may be on multiple drugs from three therapeutic classes (β-blockers, ACEI/ARBs, diuretics), and they might initiate different drugs at the different times. We used a measure of overall adherence, defined as the ratio of days of supply of medication the patient had in possession (numerator) over the number of days in the measurement period multiplied by the number of medications prescribed (denominator) during the eligible follow-up.8 We excluded days in the hospital from the eligible days in the denominator, because inpatient drugs could not be observed in Part D event data. We considered drugs in the same therapeutic class substitutable, so we did not double-count the overlapped pills for different drugs in the same class. For example, patients might switch from one β-blocker to another β-blocker and might have a few days of supply overlapping supply for the two β-blockers; we count only one set of those overlapped pills.

Racial and Ethnical Groups

We used an enhanced race variable—the Research Triangle Institute Race Code—in the Medicare beneficiary summary file. This race variable is self-reported data, but is verified by first and last name algorithms, so it has much improved sensitivity (minimum sensitivity 77 %) and a Kappa of 0.79, compared to the original race code in the Medicare data.12 The race includes six categories: White (“Whites”), Blacks (“Blacks”), Hispanics, Asian/Pacific Islander (“Asians”), American Indian/Alaska Native (“Native Americans”), and others (missing or unable to determine). We created four indicators for Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans, all relative to Whites (reference group).13

Drug Coverage and Income Groups

The standard Part D coverage includes a small deductible, about 25 % coinsurance in the initial coverage period, 100 % copayment in the coverage gap, and 5 % in the catastrophic period. Some beneficiaries choose plans that have some supplementary coverage in the coverage gap. Medicare Part D provides substantial subsidies to low-income individuals: dual eligibles (those who had both Medicare and Medicaid coverage) have drug copayments as low as $1.10 for generics, and $3.30 for brand-name drugs (2009 numbers); and if they are institutionalized, their copayment is $0.14 Those non-dual beneficiaries whose income is less than 150 % of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) who qualify for federal low-income subsidies (LIS) have drug copayments that range from $2.50 for generic and $6.30 for brand-name drugs (2009 numbers) to 15 % of total drug costs. Neither the LIS group nor the dual eligible group faces a coverage gap. Medicare Part D data have information on dual eligibility and cost-sharing variables for LIS subsidies. Using these variables, we constructed a proxy income variable with three groups: duals (whose incomes are normally <75 % FPL, but may vary across states), non-duals who have incomes between 75 % FPL and 150 % FPL, and those with incomes >150 % FPL.13,14 This enabled us to study the racial difference in adherence by income group.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted logistic regressions to model the probability of good adherence (MPR ≥ 0.75) and reported odds ratios of good adherence for each racial/ethnic group relative to Whites. This analysis was conducted separately for aged and disabled groups. We reported odds ratios of good adherence in two ways: unadjusted and fully adjusted.

In the fully adjusted model, we adjusted for three categories of beneficiary-level variables: patient demographics, insurance status, and clinical characteristics. Demographics included age bins (≤ 34, 35–50, 51–64, 65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85), and gender (1 = female; 0 = male).6 We used variables indicating Medicaid coverage (available to those under about 75 % of the Federal poverty level [FPL], but with some state variation) and non-dual federal low-income subsidies (which vary based on FPL cut-points) to create income bins: < 75 % FPL, 75–150 % FPL, and > 150 % FPL.15

We also included two indicators for supplementary drug coverage using Part D data: those with generic-coverage in the “donut hole” gap, and those with both generic and brand-name drug in the gap.

Clinical characteristics included risk scores, institutionalization (≥ 90 days in any institution), and death during the follow-up year. As in previous studies, we calculated the two prospective risk scores using prior-year diagnoses: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–Hierarchical Condition Category scores (CMS-HCC) for non-drug medical care services and the analogous prescription drug hierarchical condition category (CMS-RxHCC) scores.15,16 For those without prior-year claims, we calculated concurrent risk scores using the CMS algorithms for new enrollees, which are based only on enrollees’ age and gender.7

In addition to the income bin described above, the full model was adjusted for a zip-code–level income variable: log of median household income, and two zip-code–level variables for education: the percentage of residents over age of 25 who only completed high school, and the percentage who completed at least some college. We conducted all analyses using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 2.15.

RESULTS

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity

Table 1 presents a comparison of baseline characteristics by race and ethnicity. Compared to other races, Blacks were the most likely to be disabled enrollees whose ages were less than 65 years old, had the highest rate of institutionalization, and were the most likely to be on all three drug classes among those who were on at least one drug class.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Among Overall Population, by Race/Ethnicity

| Variable | Level | All | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 171,097 | 132,863 | 23,142 | 11,278 | 3,064 | 750 | |

| Female | 63.42 | 63.70 | 65.57 | 55.91 | 57.81 | 63.87 | |

| Persons with disability* | ≤ 34 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 1.06 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.93 |

| 35–50 | 2.89 | 1.96 | 7.93 | 1.76 | 3.59 | 6.13 | |

| 51–64 | 9.19 | 7.23 | 18.98 | 5.81 | 12.60 | 16.93 | |

| Aged* | 65–74 | 24.57 | 23.33 | 28.46 | 26.37 | 30.37 | 29.60 |

| 75–84 | 34.52 | 35.71 | 26.84 | 41.16 | 34.61 | 32.00 | |

| ≥ 85 | 28.52 | 31.61 | 16.73 | 24.54 | 18.31 | 14.40 | |

| Institutionalization | 3.11 | 3.02 | 3.78 | 2.64 | 2.86 | 3.20 | |

| Died in a year | 15.79 | 16.42 | 13.76 | 13.87 | 13.11 | 15.20 | |

| Dual eligible | 44.73 | 37.04 | 69.90 | 73.47 | 74.22 | 68.13 | |

| Non-dual LIS | 6.43 | 6.01 | 9.41 | 3.10 | 6.06 | 8.53 | |

| Gap coverage among Non-LIS | Generic and brand | 3.30 | 2.84 | 7.08 | 3.85 | 10.57 | 3.03 |

| Generic only | 19.93 | 20.00 | 16.86 | 20.65 | 24.48 | 14.55 | |

| No coverage | 76.77 | 77.17 | 76.06 | 75.50 | 64.95 | 82.42 | |

| Risk scores | Prescription drug | 0.93 ± 0.44 | 0.9 ± 0.41 | 1.04 ± 0.53 | 0.98 ± 0.41 | 1.06 ± 0.51 | 0.99 ± 0.44 |

| CMS-HCC | 1.66 ± 1.09 | 1.62 ± 1.04 | 1.75 ± 1.25 | 1.81 ± 1.19 | 1.86 ± 1.28 | 1.71 ± 1.07 | |

| Zip code level | % of high school | 57.2 ± 9.89 | 58.46 ± 9.56 | 54.79 ± 8.37 | 50.27 ± 10.81 | 49.08 ± 10.87 | 59.61 ± 8.17 |

| % of college | 21.19 ± 13.52 | 22.08 ± 13.72 | 17.33 ± 11.69 | 27.76 ± 15.07 | 17.18 ± 11.71 | 15.91 ± 9.62 | |

| Log of median household income | 10.57 ± 0.35 | 10.61 ± 0.33 | 10.37 ± 0.35 | 10.74 ± 0.38 | 10.46 ± 0.36 | 10.35 ± 0.33 | |

Plus–minus values are means ± SD. We conducted chi-square test to compare categorical variables, and analysis of variance to compare continuous variables across different racial groups. All P values are < 0.001

LIS low-income Subsidy; RxHCC prescription drug hierarchical condition category; CMS-HCC Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–Hierarchical Condition Category scores

*These numbers are years of age

Racial/Ethnic Difference in Medication Adherence

Figure 1 presents the percentage of beneficiaries who had good adherence (MPR ≥ 0.75) by race and disability status. In general, Whites had the highest proportion with good adherence, followed by Asians and Hispanics. Native Americans and Blacks were the worst in adherence for heart failure drugs. For example, among the disabled, the percentage of beneficiaries with good adherence to at least one HF drug class was 57 %, 53 %, 48 %, 44 %, and 43 % for Whites, Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans and Blacks, respectively. Compared to the disabled, a higher proportion of the aged had good adherence; and this finding was similar across all races. These race and disability differences in adherence are similar among those who were on at least one HF drug class, and those who were on all three HF drug classes.

Figure 1.

Proportion of good adherence (MPR≥0.7), by disability, and race/ethnicity sample size by disability and race/ethnicity.

Table 2 presents the estimated odd ratios (ORs) for the differences in the proportions of good adherence to HF medications for each racial group relative to Whites. Among the disabled who were on one or more HF medications, relative to Whites, Native Americans were the least likely to have good adherence (OR 0.58, 95 % CI 0.42–0.79), followed by Blacks (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.55–0.63) and Hispanics (OR 0.67, 95 % CI 0.61–0.74) after full adjustment of covariates. However, Native Americans and Asians were not statistically significantly different from Whites, partially due to small sample sizes. Our findings for the aged are more robust than those for the disabled, because of larger sample sizes. After adjusting for covariates, all four ethnic groups were significantly less likely to have good adherence to HF medications than Whites. For example, among those who were on one or more HF medications, Native Americans were the least likely to have good adherence (OR 0.58, 95 % CI 0.49–0.69), followed by Blacks (OR 0.61, 95 % CI 0.59–0.64), Hispanics (OR 0.62, 95 % CI 0.59–0.65), and Asians (OR 0.70, 95 % CI 0.65–0.76).

Table 2.

Racial/Ethnic Difference in Medication Adherence Among Heart Failure Patients

| Disabled | Aged | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Native | 0.585 | (0.43, 0.80) | 0.580 | (0.42, 0.79) | 0.606 | (0.51, 0.72) | 0.581 | (0.49, 0.69) |

| Black | 0.589 | (0.55, 0.63) | 0.590 | (0.55, 0.63) | 0.642 | (0.62, 0.66) | 0.614 | (0.59, 0.64) |

| Hispanic | 0.694 | (0.63, 0.77) | 0.670 | (0.61, 0.74) | 0.664 | (0.64, 0.69) | 0.622 | (0.59, 0.65) |

| Asian | 0.884 | (0.68, 1.15) | 0.889 | (0.68, 1.16) | 0.768 | (0.71, 0.83) | 0.703 | (0.65, 0.76) |

| White | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

Bold denotes statistically significant at p value < 0.05

“Adjusted” means adjusted for all covariates discussed in the Statistical Analysis section

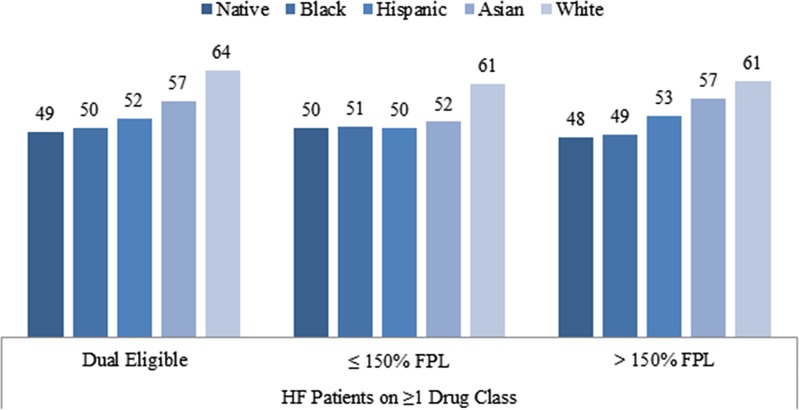

Racial/Ethnic Difference in Medication Adherence, by Income

In order to determine if racial/ethnic difference can be explained by differences in income or participation in the LIS program, we conducted additional analyses and reported odds ratios of good adherence for each racial/ethnic group relative to Whites separately for each income/eligibility group in Tables 3, and Figure 2. In general, racial disparities on good adherence were persistently observed among Blacks and Hispanics across income groups. For example, among the dual eligible, Blacks were less likely to have good adherence to at least one HF medication (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.57–0.62) after adjusting for all the covariates except for income. However, racial differences among Native Americans and Asians were not consistently observed across different income groups. For example, among non-dual LIS recipients (75–150 % FPL), proportions of Native Americans and Asians with good adherence to HF medications were not significantly different from Whites.

Table 3.

Racial/Ethnic Difference in Medication Adherence Among Heart Failure Patients, by Income

| Dual eligible | ≤ 150 % FPL | > 150 % FPL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Native | 0.551 | (0.46, 0.66) | 0.567 | (0.47, 0.68) | 0.625 | (0.37, 1.05) | 0.652 | (0.39, 1.10) | 0.566 | (0.42, 0.77) | 0.598 | (0.44, 0.81) |

| Black | 0.563 | (0.54, 0.58) | 0.594 | (0.57, 0.62) | 0.663 | (0.60, 0.73) | 0.687 | (0.62, 0.76) | 0.584 | (0.55, 0.62) | 0.610 | (0.57, 0.65) |

| Hispanic | 0.614 | (0.59, 0.64) | 0.607 | (0.58, 0.64) | 0.633 | (0.54, 0.74) | 0.651 | (0.55, 0.77) | 0.689 | (0.63, 0.75) | 0.694 | (0.64, 0.76) |

| Asian | 0.735 | (0.67, 0.8) | 0.688 | (0.63, 0.75) | 0.670 | (0.44, 1.01) | 0.679 | (0.45, 1.03) | 0.795 | (0.68, 0.93) | 0.791 | (0.68, 0.93) |

| White | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

Bold denotes statistically significant at p value < 0.05

“Adjusted” models were adjusted for all covariates except for income, as discussed in the Statistical Analysis section

Figure 2.

Racial/ethnic difference in adherence to heart failure medications, by income sample size, by income and race/ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we found that rates of good adherence are lower among Blacks, Native Americans, Hispanics and Asians than Whites. The racial disparities in adherence persist after the adjustment for other demographic variables, zip-code–level income and education, drug coverage, insurance status, risk scores, and other factors. We also found that disabled Medicare beneficiaries (under age 65 who are enrolled in Medicare because of the disability criteria) are less likely to be good adherents to their medication therapy, compared to older Medicare beneficiaries. This is true for each racial/ethnic group. In our study sample, 15 % was disabled and 85 % was aged.

The adherence data on the disabled Medicare population were relatively less known. One recent study has showed that disabled Medicare beneficiaries with a recent history of myocardial infarction had much poorer adherence to essential drugs compared to similar aged population;13 in addition, the racial difference in adherence is more pronounced among the disabled than the aged. Our findings here are consistent with previous findings.

Adherence to medications is lower among minority patients compared to Whites.17 A recent meta-analysis shows that non-Whites had a 53 % greater odds of non-adherence to statin therapy than White patients.18 In a large review of long-term adherence to evidence-based medication therapy in heart disease, non-Whites were less likely to consistently use β-blockers, lipid-lowering agents, and ACEIs in adjusted analyses, and were less likely to consistently use the combination of aspirin, β-blockers, and lipid-lowering therapy.5 Black beneficiaries, compared to Whites, were significantly less likely to fill at least one HF prescription (odds ratio 0.43, P < 0.01), among a large sample of Medicaid beneficiaries with HF in 1999 from several states.19 In general, the data on Native Americans, Hispanics and Asians were relatively less known, due to small sample size and the lack of the national data. Our study reports poorer adherence among Hispanics and Native Americans at the national level.

Our study has some limitations. First, because the race code is primarily self-reported data, some racial misclassification is possible; although the enhanced race code is much better than the original one.12 Second, there are limitations embedded in using claims data: we cannot observe whether a drug filled was actually taken; we cannot observe all contradictions to the studied drugs, e.g. measures such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and LDL-C, a contradiction to ACEI. We assumed that if we see a prescription filled in the claims for an ACEI, the physician who prescribed the drug had evaluated patient’s profile for contraindications. Third, we cannot observe drugs filled but not covered by the Part D plans. For example, if drugs were not covered on the plan’s formulary, then they would not be in the claims data. Although many drugs filled in the $4 programs can be reimbursed by Medicare Part D plans, if Medicare beneficiaries do not present their Medicare card when filling a $4 drug, then the drug would not be observed in Part D data.20 Last, claims data do not have education information, so we had to use zip-code–level data.

We found that racial disparity in adherence to heart failure drugs persists after the implementation of Part D, even though among Medicare beneficiaries who have relatively complete drug coverage, we found that there are still significant differences in rates of good adherence across racial/ethnic groups, after adjusting for health status and other factors. Considerable research suggests that adherence to medications is an important driver of clinical outcomes for patients with chronic diseases.6,21 In some cases, greater adherence may even result in lower total medical expenditures.22,23 The rate of adherence to heart failure drugs is still alarmingly low, with the large expansion of drug coverage under Medicare Part D. Our findings indicate that even if drugs are completely covered, racial/ethnic differences would likely persist. Part of this racial/ethnic difference could be because of patients’ health beliefs.24 Thus, policies relying solely on lowering drug costs will not be effective in eliminating the racial disparities, and they should be combined with other strategies that target health beliefs. Our findings suggest that physicians should be particularly sensitive to their disabled and non-White patients. Policy makers should be more attentive to strategies for improving long-term adherence.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Institute of Medicine, National Institute of Mental Health (No. RC1 MH088510) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. R01 HS018657) to Dr. Zhang.

Role of the Sponsor

Sponsors played no role in the study conduct, data analysis, or report generation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Appendix

REFERENCES

- 1.Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas: American Heart Association 2006; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, et al. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119(14):1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J-R, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14(3):203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80 % BMJ. 2003;326(7404):1419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newby LK, Allen LaPointe NM, Chen AY, et al. Long-term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2006;113(2):203–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.505636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2088–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroupe KT, Teal EY, Weiner M, Gradus-Pizlo I, Brater DC, Murray MD. Health care and medication costs and use among older adults with heart failure. Am J Med. 2004;116(7):443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Wu S, Fendrick AM, Baicker K. Variation in medication adherence in heart failure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013:1–2. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2509

- 9.Neuman P, Strollo MK, Guterman S, et al. Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report: findings from a 2006 national survey of seniors. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):w630–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Lave JR, Donohue JM, Fischer MA, Chernew ME, Newhouse JP. The impact of Medicare Part D on medication adherence among older adults enrolled in Medicare-Advantage products. Med Care. 2010;48(5):409–17. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d68978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Geographic Variation in Health Care Spending and Promotion of High-Value Care - Interim Report. IOM. 2013. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2013/Geographic-Variation-in-Health-Care-Spending-and-Promotion-of-High-Care-Value-Interim-Report.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 12.Bonito A, Bann C, Eicheldinger C, Carpenter L. Creation of new race-ethnicity codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) indicators for medicare beneficiaries. Final Report. Sub-Task 2. (Prepared by RTI International for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services through an interagency agreement with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Policy, under Contract No. 500-00-0024, Task No. 21). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. 2008. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/medicareindicators/medicareindicators.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 13.Zhang Y, Baik SH, Chang CC, Kaplan CM, Lave JR. Disability, race/ethnicity, and medication adherence among Medicare myocardial infarction survivors. Am Heart J. 2012;164(3):425–33 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser Family Foundation. Low-income assistance under the Medicare drug benefit. Menlo Park, CA, USA. 2009. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7327-05.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 15.Zhang Y, Baik SH, Fendrick AM, Baicker K. Comparing local and regional variation in health care spending. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(18):1724–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1203980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2011 Model diagnosis and model softweare—RxHCC model software. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Baltimore, MD, USA. 2011. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Risk_adjustment.html. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 17.Davis AM, Vinci LM, Okwuosa TM, Chase AR, Huang ES. Cardiovascular health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):29S–100S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewey J, Shrank WH, Bowry AD, Kilabuk E, Brennan TA, Choudhry NK. Gender and racial disparities in adherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2013;165(5):665–78 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagchi AD, Esposito D, Kim M, Verdier J, Bencio D. Utilization of, and adherence to, drug therapy among Medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure. Clin Ther. 2007;29(8):1771–83. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Gellad WF, Zhou L, Lin Y-J, Lave JR. Access to and use of $4 Generic Programs in Medicare. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1251–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijeysundera HC, Machado M, Farahati F, et al. Association of temporal trends in risk factors and treatment uptake with coronary heart disease mortality, 1994–2005. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1841–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Lave JR, O’Donnell G, Newhouse JP. The effect of Medicare Part D on drug and medical spending. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):52–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu J, Price M, Huang J, et al. Unintended consequences of caps on Medicare drug benefits. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2349–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):555–67. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]