Abstract

Purpose

Topotecan is widely used for refractory solid tumors but multi-drug resistance may occur due to tumor expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Since erlotinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), also inhibits several ABC transporters, we performed a phase I study to evaluate the safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of intravenous topotecan given in combination with erlotinib.

Methods

Patients received 150 mg of oral erlotinib daily and a 30 min intravenous infusion of topotecan on days 1 to 5 of a 21-day cycle. Dosage escalation of topotecan occurred with a starting dosage of 0.75 mg/m2. The pharmacokinetics of topotecan were evaluated on day 1 of cycle 1 without erlotinib and on day 1 of cycle 2 or 3 with erlotinib.

Results

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled. The maximum tolerated dosage was determined to be 1.0 mg/m2. Dose-limiting toxicities included neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. The average duration of treatment was 97 days. Two partial responses were observed. Topotecan clearance and exposure were similar with and without erlotinib.

Conclusions

The combination of topotecan and erlotinib is tolerable at clinically effective doses. Erlotinib does not affect the disposition of topotecan to a clinically significant extent.

Keywords: topotecan, erlotinib, refractory solid tumors, pharmacokinetics, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Topotecan therapy has been widely used in the treatment of refractory solid tumors [1]. However, the efficacy of topotecan may be reduced due to multi-drug resistance in patients, especially among patients who have received prior chemotherapy [2]. Multi-drug resistance is mediated by the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family, which act as efflux pumps that transport anticancer drugs out of the target cells, thereby reducing the amount of drug in the cells. Topotecan is a substrate for ABC transporters such as breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP; ABCG2), P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1), and multi-drug resistant protein 4 (MRP4; ABCC4) [3–5]. These proteins induce multi-drug resistance in many types of cancers intrinsically and can also be induced due to chemotherapy [6]. Inhibition of ABC transporters may overcome drug resistance and should translate into enhanced antitumor effect by increasing the tumor intracellular drug concentration.

Erlotinib is an orally bioavailable 4-anilinoquinazoline tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and has been approved for the first-line treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer in combination with gemcitabine and for second-line therapy of non-small cell lung cancers [7,8]. EGFR is over-expressed or mutated in many solid tumor types, including non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal, breast, pancreas, ovary, head and neck, esophagus, and brain tumors [9–16]. Clinical trials have shown that erlotinib monotherapy is active against many solid tumors [17–20]. Erlotinib, like other structurally similar tyrosine kinase inhibitors, inhibits several ABC transporters, including P-gp and BCRP. This is likely to have many effects including altering the disposition of drugs that are substrates for these transporters (e.g., topotecan), and reversing drug resistance mediated by these transporters [21]. Murine models demonstrate an increase in topotecan levels in cerebrospinal fluid and in gliomas with the addition of erlotinib, suggesting a role for combination therapy in brain tumors [22,23]. Therefore, addition of erlotinib to topotecan therapy may have application in the treatment of refractory solid tumors.

This phase I study was performed to assess whether erlotinib can be used in combination with topotecan in patients with solid tumors. The combination regimen consisted of 5 days of intravenous topotecan with continuous oral erlotinib therapy. The primary objectives were to estimate the maximum tolerated dosage (MTD) of topotecan in this combination, to identify the dose-limiting toxicities (DLT), and to evaluate the pharmacokinetic profile of intravenous topotecan with erlotinib.

METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients had a histologically confirmed malignancy that was metastatic or unresectable and for which standard curative or palliative measures did not exist or were no longer effective. Patients were older than 18 years of age; had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 1; a life expectancy of greater than 12 weeks; and adequate organ and marrow function. Exclusion criteria included more than 5 prior lines of therapy, prior chemotherapy within the last 3 weeks, prior radiation within the last 8 weeks, major surgery within the last 4 weeks, and hormonal therapy within the last 2 weeks prior to enrollment; administration of concurrent cancer therapy, warfarin, and potent inhibitors or inducers of cytochrome P4503A4. All patients gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study, and the Western Institutional Review Board approved the protocol.

Study design and treatment

This was an open-label phase I study that examined the MTD of topotecan when delivered in combination with continuous erlotinib therapy. Patients were enrolled to this study in two stages. In the initial stage, patients were enrolled to address determination of MTD. Additional patients were enrolled to provide sufficient data for assessment of pharmacokinetic parameters.

Dose escalation followed a standard 3 + 3 cohort design. Three patients were enrolled at the starting dosage level. In the absence of a DLT, three patients were treated at the next dosage level. If one DLT occurred, three more patients were treated at the same dosage level; if no further DLTs occurred, then dosage escalation was continued. If > 1/3 or 1/6 experienced a DLT, the current dosage was reduced. The MTD was the highest dosage at which not more than 1/6 patients experienced a DLT.

Adverse events were graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 for all cycles, but DLTs were determined for cycle 1 only. A hematologic DLT was defined as grade 4 neutropenia lasting > 7 days, grade 3/4 neutropenia with fever >38.5°C, grade 3 thrombocytopenia > 7 days, grade 4 thrombocytopenia, or any combination of the above. A non-hematologic DLT was defined as any grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity attributable to topotecan, erlotinib, or the combination, not including grade 3 nausea and vomiting responsive to antiemetics, grade 3 fever or infection, grade 3 diarrhea responsive to antidiarrheal therapy, and grade 3 transaminase elevations that returned to ≤ grade 1 or ≤ baseline within 7 days of interrupting erlotinib treatment.

Dosage levels 1, 2, and 3 were 0.75 mg/m2, 1.0 mg/m2, and 1.25 mg/m2 of topotecan, respectively, combined with 150 mg of erlotinib at each level. The initial dosage level was based on half the MTD of intravenous topotecan used as monotherapy in patients with solid tumors [24]. Topotecan was administered as a 30 min infusion on days 1 to 5 of each 21-day cycle. Erlotinib was administered orally on each day, except day 1 of the first cycle to allow characterization of topotecan pharmacokinetic parameters without coadministration of erlotinib. For the cohort of patients enrolled for determination of MTD, patients were allowed 4 cycles of the combination therapy (topotecan + erlotinib), then went onto monotherapy (single agent erlotinib). For the cohort of patients enrolled for pharmacokinetic parameter estimation, the treating physician determined how many cycles of the combination therapy patients received based on clinical benefit. Single agent erlotinib could then follow at the end of the combination therapy.

Antitumor response assessment

Tumor assessment at screening, during treatment, and at the end of treatment was evaluated using CT or MRI. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines, version 1.0, were used to classify patient response. An objective response was defined as those patients who had a complete or partial response.

Pharmacogenetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using standard procedures, and 10 ng of DNA was used for genotyping. CYP3A4*1B was genotyped as described [25] with modified PCR conditions: 95°C for 5 min, 30 × (95°C for 60 s, 62°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s), and 72°C for 3 min. Second-round PCR was performed with 1 µL of a 1:20 dilution of the product as follows: 95°C for 3 min, 28 × (95°C for 30 s, 65°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s), and 72°C for 3 min. ScrF1 was used to digest 5 µL of sample, and fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. CYP3A5*3C polymorphisms were analyzed as described previously [26], as were the ABCB1 polymorphisms in exons 21 and 26 [27]. Amplification product (4 µl) was sequenced by using the forward PCR primer. The ABCG2 34G>A and 421C>A polymorphisms were genotyped as described [28] with the following modifications: 10 ng of genomic DNA was used as template, and annealing for the PCR reactions was done at 55°C. Amplification product (4 µl) was sequenced by using the forward PCR primer. ABCG2 promoter and intron 1 polymorphisms at −15622, −15994, 1143 and 16702 [29] were identified by PCR amplification and direct sequencing. PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 min, 35 × (94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s) and 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Pharmacokinetic studies were performed prior to initiating erlotinib therapy (day 1 of cycle 1) and at steady-state erlotinib conditions (day 1 of cycle 2 or cycle 3). Erlotinib was administered 1 h prior to topotecan administration on days 1 of cycle 2 and cycle 3. Venous blood draws for topotecan pharmacokinetics were performed prior to administration and at 5 min, 1, 2, and 3 hours after the end of the topotecan infusion according to a limited sampling model [30].

Whole blood was collected in heparin tubes and immediately centrifuged for 2 min at ×7,000 g. Plasma was separated and stored at −20°C or −80°C until analysis. Urine was collected continuously for 24 h beginning at the start of the topotecan infusion. A 10 mL aliquot was removed and frozen at −20°C or −80°C until analysis. An isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay with fluorescence detection was used to measure the total topotecan concentrations in plasma and urine as previously described [31].

A two-compartment pharmacokinetic model was used to fit the total plasma topotecan concentration-time data for each patient using a maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation with the importance sampling expectation maximization algorithm in ADAPT 5 [32]. Individual pharmacokinetic parameters estimated included distributional clearance (CLd), terminal clearance (CLt), volume of distribution of the central compartment (Vc), and volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment (Vp). The Bayesian prior mean and variance of each parameter was determined from a population pharmacokinetic analysis of topotecan in adult patients [33]. Area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0->∞) values for each study were calculated using the model estimated clearance value and dosage. Renal clearance (CLrenal) was calculated with the following equation:

CLrenal = CLt X Fe

where CLt is the terminal topotecan clearance and Fe is the fraction of topotecan eliminated unchanged in the urine. If Fe was greater than 1 for an individual, data from that individual was not used for analysis of renal clearance. Differences between cycle 1 and cycle 2/3 pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated with a paired t-test.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled to the study in two stages. In the initial stage, sixteen patients were enrolled to determine the MTD. Following this determination, an additional 13 patients were enrolled to provide additional data for assessment of the effect of erlotinib on topotecan pharmacokinetics. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic or Clinical Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 58.5 | - |

| Range | 41.8 – 78.0 | - |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 | 34.5 |

| Female | 19 | 65.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African-American | 8 | 27.6 |

| Caucasian | 21 | 72.4 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 7 | 24.1 |

| 1 | 22 | 75.9 |

| Tumor type | ||

| Breast | 2 | 6.9 |

| Colorectal | 5 | 17.2 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2 | 6.9 |

| Non-Small Cell Lung | 2 | 6.9 |

| Ovarian | 4 | 13.8 |

| Pancreatic | 2 | 6.9 |

| Small Cell Lung | 5 | 17.2 |

| Other | 7 | 24.1 |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 1 | 5 | 17.2 |

| 2 | 9 | 31.0 |

| 3 | 6 | 20.7 |

| > 3 | 9 | 31 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Safety and tolerability

DLTs were assessed during the first cycle of combination topotecan and erlotinib therapy (days 1–21). Table 2 reports the DLTs of 28 patients by dosage level, excluding one patient who withdrew prior to completion of the first cycle. None of the initial group enrolled at dosage level 1 (0.75 mg/m2) experienced DLTs. At dosage level 2 (1.0 mg/m2) in the initial group, 1 of 6 patients who completed the first cycle experienced Grade 4 neutropenic fever and Grade 3 decrease in urine output. At dosage level 3 (1.25 mg/m2) in the initial group, 2 of 6 patients experienced DLTs (Grade 4 neutropenia and Grade 4 thrombocytopenia with hypotension and shortness of breath). On this basis, 1.0 mg/m2 was identified as the MTD. An additional 13 patients were then enrolled to collect further pharmacokinetic data. The first 8 of these patients were enrolled at dosage level 2 (1.0 mg/m2). Although DLT was not the primary outcome for analysis of this group of patients, 4 of the 8 patients experienced a DLT. As a result, the remaining 5 patients were enrolled at dosage level 1, and none experienced a DLT.

Table 2.

Dose Limiting Toxicity Types by Dose Level for Two Groups

| Initial 16 Patients | Additional 13 Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLT Typea | Level 1 (n =3)b | Level 2 (n = 6)b, c | Level 3 (n = 6)b | Level 2 (n = 8)b | Level 1 (n = 5)b | |

| Neutropenic Fever (Gr 4) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Neutropenia > 7 days (Gr 4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Thrombocytopenia (Gr 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thrombocytopenia (Gr 4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Decreased Urine Output (Gr 3) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypotension (Gr 3) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pneumonia (Gr 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Shortness of Breath (Gr 3) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Patients with any DLT | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

Dose Limiting Toxicity (DLT) was graded (Gr) per the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Level 1 = topotecan 0.75 mg/m2, Level 2 = topotecan 1.0 mg/m2, Level 3 = topotecan 1.25 mg/m2.

One patient from the Initial 16 withdrew early from Level 2 and was excluded.

All patients experienced at least one adverse event. Irrespective of grade, the most common adverse events were in blood and lymphatic system disorders (26/29 cases, 90%): anemia (62%), neutropenia (55%) and thrombocytopenia (59%). General disorders were reported in 19/26 cases (66%) with fatigue the most frequent complaint (38%). Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders were noted in 18/29 cases (62%) with rash being the most frequent (48%). Respiratory disorders and gastrointestinal disorders were reported in 17/29 (59%) and 16/29 cases (55%), respectively. In the former the most frequent complaint was shortness of breath (21%) and in the latter, diarrhea (38%).

Dose reductions for topotecan at dosage level 3 occurred for two patients among the first 16 enrolled, and both were reduced to dosage level 2 for the remainder of the study following occurrence of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Among the final 13 patients enrolled, dose reductions occurred for topotecan from dosage level 2 down to dosage level 1 for 2 patients with thrombocytopenia.

Antitumor response

Table 3 reports best overall response by dosage level of 28 patients, excluding the one early withdrawal patient. No patients had a complete response, 2 patients (7%) had a partial response, 12 patients (43%) had stable disease, 8 patients (29%) had progressive disease, and 6 patients were non-evaluable. Reasons for patients being non-evaluable included death (n = 2), adverse events (n = 2), and other reasons (n = 2). The overall disease control rate (partial response + stable disease) was 50% (14 of 28 patients). Median progression-free survival time was 154 days (95% CI, 54 – 94). Overall survival time was 362 days (95% CI, 215 – 730). We observed two partial responses, occurring in patients enrolled on dosage levels 2 and 3. One patient had Stage IV colorectal cancer and the other patient had Stage IV ovarian cancer. Both of these patients had received three lines of prior chemotherapy before enrolling in this study.

Table 3.

Summary of Radiologic Responses

| No. of Patients |

All Patients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best Overall Response | 0.75 mg/m2 | 1.0 mg/m2 | 1.25 mg/m2 | (n = 28) | |

| (n = 8) | (n = 14) | (n = 6) | No. | % | |

| Complete response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Partial response | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Stable disease | 3 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 42.9 |

| Progressive disease | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 28.6 |

| Not evaluable | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 21.4 |

Pharmacogenetics

Patients were genotyped for polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), and P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1). A summary of the frequency of the polymorphisms is in Table 4. The associations between genetic polymorphisms and topotecan pharmacokinetics were explored by visual inspection of plots of pharmacokinetic parameters from Cycle 1 stratified by genotype. No statistically significant differences were observed in any pharmacokinetic parameters among patients of different genotypes (Mann-Whitney U test; p>0.05).

Table 4.

Summary of Patient Genotypes

| Gene | Polymorphism | Wild-type | Heterozygous | Variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | *1 | 20/28 | 0/28 | 8/28 |

| CYP3A5 | *3 | 19/28 | 3/28 | 6/28 |

| *6 | 27/29 | 2/29 | 0/29 | |

| UGT1A1 | *28 | 15/29 | 14/29 | 0/29 |

| BCRP | 34G>A | 26/29 | 3/29 | 0/29 |

| 421C>A | 25/29 | 4/29 | 0/29 | |

| P-gp | 2677G>T | 13/29 | 12/29 | 4/29 |

| 3435C>T | 13/29 | 7/29 | 9/29 |

Pharmacokinetics

Cycle 1 pharmacokinetic studies of topotecan were performed for all 29 consenting patients. One patient withdrew consent prior to cycle 2/3 studies, and 8 patients went off-study prior to cycle 2/3 studies. Cycle 2/3 pharmacokinetic studies were performed for the remaining 20 patients. Goodness-of-fit plots showed that the model described the data well for all studies, except one. Data from this patient were excluded from subsequent analysis.

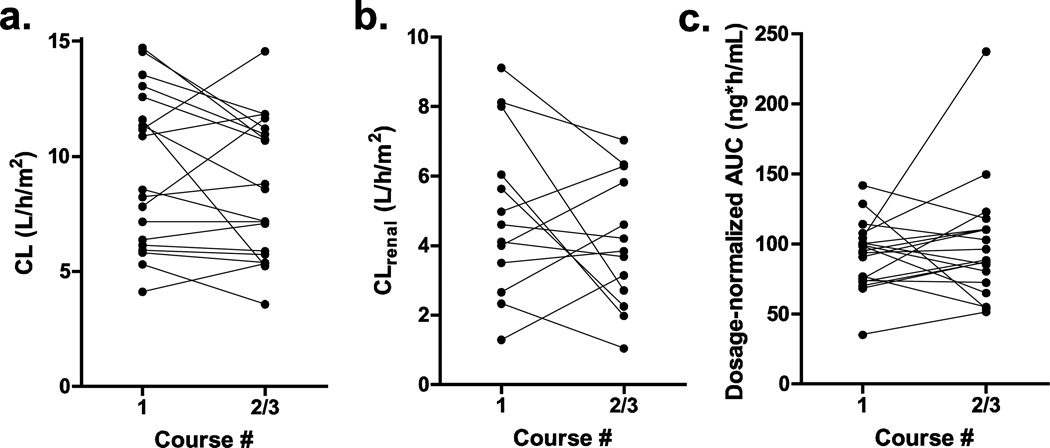

The effect of erlotinib on topotecan disposition was assessed by comparing pharmacokinetic parameters between Cycle 1 and Cycle 2/3 (Table 5). The mean clearance was 8.6% lower in Cycle 2/3 compared to Cycle 1 (Fig 1a, p = 0.17). Similarly, the mean renal clearance was decreased by 17.8% (Fig 1b, p = 0.21). The mean dosage-normalized AUC was 8.0% higher in Cycle 2/3 than in Cycle 1 (Fig 1c, p = 0.45).

Table 5.

Summary of Pharmacokinetic Parameters

| CL (L/h/m2) | CLrenal(L/h/m2) | Dosage-normalized AUC (ng*h/mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | 1 | 2/3 | 1 | 2/3 | 1 | 2/3 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.41 (3.40) | 8.60 (3.04) | 4.95 (2.38) | 4.07 (1.87) | 91.8 (24.1) | 99.1 (42.2) |

| Median | 8.55 | 8.57 | 4.61 | 3.84 | 94.7 | 88.2 |

| Range | 4.11–14.7 | 3.56–14.6 | 1.29–9.12 | 1.04–7.04 | 35.1–142 | 51.4–237.2 |

| n | 19 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 19 | 19 |

Figure 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of total topotecan without erlotinib (Cycle 1) and with erlotinib (Cycle 2/3). (a) terminal clearance (L/h/m2), (b) renal clearance (L/h/m2), and (c) dosage-normalized AUC (ng*h/mL)

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that erlotinib can be safely combined with topotecan. The major adverse events were hematologic. These adverse events were consistent with those observed in single agent trials of erlotinib and topotecan. The antitumor response was expected given the advanced stage of disease of those patients enrolled.

Topotecan is eliminated though renal and biliary excretion, with only a minor contribution from hepatic metabolism [34]. Because P-gp and BCRP may contribute to renal and biliary excretion, it is important to know whether inhibitors of these transporters affect topotecan clearance. Administration of daily erlotinib did not have a clinically significant effect on topotecan clearance or exposure. The mean terminal clearance of topotecan was 8.6% lower when patients were receiving erlotinib compared to when they received topotecan as a single agent, although this difference was not statistically significant. Ideally, patients would be randomized to receive single agent or combination therapy first, but randomization would not be appropriate for the design of this study. One possible reason that no effect of erlotinib administration on topotecan clearance could be detected is the contribution of other transporters, such as organic anion transporter 3, to topotecan clearance [35].

Targeted therapies such as erlotinib with single-agent activity may enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Modest tumor response rates and symptom control are achieved with some of these combinations. Erlotinib plus topotecan may be considered a useful salvage therapy for patients with a good performance status that over-express the EGFR. A single arm phase II study of topotecan plus erlotinib was recently enrolling patients with recurrent ovarian cancer previously treated with topotecan; however, the study has now been terminated due to slow accrual. This study was evaluating topotecan 0.4 mg/m2/day administered via continuous infusion for 9 days beginning on Day 1 of every 21 day cycle. Additionally, patients would receive erlotinib 150 mg daily Days 1–9 in a cycle of 21 days [36].

Other combination therapies of EGFR inhibitors and chemotherapy have been studied. A clinical trial evaluated the dual EGFR1/HER2 inhibitor lapatinib in combination with topotecan in patients with platinum refractory/resistant ovarian cancer. One partial response and three patients deriving clinical benefit were observed in a group of 18 patients [37]. In another phase II trial of topotecan and lapatinib in relapsed/refractory ovarian cancer, 35 patients were evaluable for treatment response. Five patients demonstrated a partial response and another 12 patients experienced disease stabilization [38].

In conclusion, this study suggests that topotecan and erlotinib can be administered together at clinically effective doses, and that such a regimen is associated with acceptable levels of hematologic and non-hematologic toxicity. Pharmacokinetic analysis indicates that administration of erlotinib at the standard dose of 150 mg has no significant effect on topotecan systemic clearance. This combination shows evidence of antitumor activity in patients with refractory solid tumors. Further studies are needed to establish the efficacy of this combination.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Cancer Center Support CA 21765, GlaxoSmithKline, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Dr. Stewart and Dr. Schwartzberg received study funding from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Tauer has served in a consultant/advisory role to GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Portions of this research were previously presented at the 2008 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 30–June 3, Chicago, IL.

All other authors report that they have no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pizzolato JF, Saltz LB. The camptothecins. Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2235–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon GR, Wagner H. Small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):259S–271S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.259s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruijtzer CM, Beijnen JH, Rosing H, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Schot M, Jewell RC, Paul EM, Schellens JH. Increased oral bioavailability of topotecan in combination with the breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein inhibitor GF120918. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(13):2943–2950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diestra JE, Scheffer GL, Catala I, Maliepaard M, Schellens JH, Scheper RJ, Germa-Lluch JR, Izquierdo MA. Frequent expression of the multi-drug resistance-associated protein BCRP/MXR/ABCP/ABCG2 in human tumours detected by the BXP-21 monoclonal antibody in paraffin-embedded material. J Pathol. 2002;198(2):213–219. doi: 10.1002/path.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian Q, Zhang J, Chan SY, Tan TM, Duan W, Huang M, Zhu YZ, Chan E, Yu Q, Nie YQ, Ho PC, Li Q, Ng KY, Yang HY, Wei H, Bian JS, Zhou SF. Topotecan is a substrate for multidrug resistance associated protein 4. Curr Drug Metab. 2006;7(1):105–118. doi: 10.2174/138920006774832550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(1):48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA, Campos D, Lim R, Ding K, Clark G, Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Ptasynski M, Parulekar W. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, van Kooten M, Dediu M, Findlay B, Tu D, Johnston D, Bezjak A, Clark G, Santabarbara P, Seymour L. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosell R, Moran T, Carcereny E, Quiroga V, Molina MA, Costa C, Benlloch S, Taron M. Non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations in the EGFR kinase domain. Clin Transl Oncol. 12(2):75–80. doi: 10.1007/S12094-010-0473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saif MW. Colorectal cancer in review: the role of the EGFR pathway. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 19(3):357–369. doi: 10.1517/13543781003593962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milanezi F, Carvalho S, Schmitt FC. EGFR/HER2 in breast cancer: a biological approach for molecular diagnosis and therapy. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008;8(4):417–434. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papageorgio C, Perry MC. Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(7):647–657. doi: 10.1080/07357900701522653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafky JM, Wilken JA, Baron AT, Maihle NJ. Clinical implications of the ErbB/epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor family and its ligands in ovarian cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785(2):232–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinolo AA, Amornphimoltham P, Squarize CH, Castilho RM, Patel V, Gutkind JS. Dysregulated molecular networks in head and neck carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pande AU, Iyer RV, Rani A, Maddipatla S, Yang GY, Nwogu CE, Black JD, Levea CM, Javle MM. Epidermal growth factor receptor-directed therapy in esophageal cancer. Oncology. 2007;73(5–6):281–289. doi: 10.1159/000132393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Jawahri A, Patel D, Zhang M, Mladkova N, Chakravarti A. Biomarkers of clinical responsiveness in brain tumor patients : progress and potential. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12(4):199–208. doi: 10.1007/BF03256285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarwala SS, Siu LL. Multicenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):77–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon AN, Finkler N, Edwards RP, Garcia AA, Crozier M, Irwin DH, Barrett E. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib HCl, an epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: results from a phase II multicenter study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(5):785–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickler MN, Cobleigh MA, Miller KD, Klein PM, Winer EP. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(1):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsley CA, Major P, Siu LL, Dancey J, Chen E, Pond GR, Nicklee T, Ho J, Hedley D, Tsao M, Moore MJ, Oza AM. Phase II study of erlotinib (OSI-774) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(8):1136–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z, Peng XX, Kim IW, Shukla S, Si QS, Robey RW, Bates SE, Shen T, Ashby CR, Jr, Fu LW, Ambudkar SV, Chen ZS. Erlotinib (Tarceva, OSI-774) antagonizes ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 and ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2-mediated drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2007;67(22):11012–11020. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carcaboso AM, Elmeliegy MA, Shen J, Juel SJ, Zhang ZM, Calabrese C, Tracey L, Waters CM, Stewart CF. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib enhances topotecan penetration of gliomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4499–4508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen J, Carcaboso AM, Hubbard KE, Tagen M, Wynn HG, Panetta JC, Waters CM, Elmeliegy MA, Stewart CF. Compartment-specific roles of ATP-binding cassette transporters define differential topotecan distribution in brain parenchyma and cerebrospinal fluid. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5885–5892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowinsky EK, Grochow LB, Hendricks CB, Ettinger DS, Forastiere AA, Hurowitz LA, McGuire WP, Sartorius SE, Lubejko BG, Kaufmann SH, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of topotecan: a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:647–656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadlubar FF, Berkowitz GS, Delongchamp RR, Wang C, Green BL, Tang G, Lamba J, Schuetz E, Wolff MS. The CYP3A4*1B variant is related to the onset of puberty, a known risk factor for the development of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Goldstein JA. Functionally defective or altered CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 single nucleotide polymorphisms and their detection with genotyping tests. Pharmacogenomics. 2005;6(4):357–371. doi: 10.1517/14622416.6.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng H, Webber S, Zeevi A, Schuetz E, Zhang J, Lamba J, Bowman P, Burckart GJ. The MDR1 polymorphisms at exons 21 and 26 predict steroid weaning in pediatric heart transplant patients. Hum Immunol. 2002;63(9):765–770. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zamber CP, Lamba JK, Yasuda K, Farnum J, Thummel K, Schuetz JD, Schuetz EG. Natural allelic variants of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and their relationship to BCRP expression in human intestine. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poonkuzhali B, Lamba J, Strom S, Sparreboom A, Thummel K, Watkins P, Schuetz E. Association of breast cancer resistance protein/ABCG2 phenotypes and novel promoter and intron 1 single nucleotide polymorphisms. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(4):780–795. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner PK, Iacono LC, Panetta JC, Santana VM, Daw NC, Gajjar A, Stewart CF. Development and validation of limited sampling models for topotecan lactone pharmacokinetic studies in children. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(4):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart CF, Baker SD, Heideman RL, Jones D, Crom WR, Pratt CB. Clinical pharmacodynamics of continuous infusion topotecan in children: systemic exposure predicts hematologic toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(9):1946–1954. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'argenio DZ, Schumitzky A. Biomedical Simulations Resource. Los Angeles: 2009. ADAPT 5 User’s Guide: Pharmacokinetic/ Pharmacodynamic Systems Analysis Software. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mould DR, Holford NH, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH, Hutson PR, Rosing H, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Rowinsky EK, Schiller JH, Russo M, Ross G. Population pharmacokinetic and adverse event analysis of topotecan in patients with solid tumors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71(5):334–348. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.123553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dennis MJ, Beijnen JH, Grochow LB, van Warmerdam LJ. An overview of the clinical pharmacology of topotecan. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(1 Suppl 5):S5–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumoto S, Yoshida K, Ishiguro N, Maeda T, Tamai I. Involvement of rat and human organic anion transporter 3 in the renal tubular secretion of topotecan [(S)-9-dimethylaminomethyl-10-hydroxy-camptothecin hydrochloride] J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(3):1246–1252. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Continuous infusion topotecan with erlotinib for topotecan pretreated ovarian cancer: tumor features and phase II/pharmacokinetic evaluation. [Accessed 2013 Nov 27];OSI Pharmaceuticals. 2009 http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01003938. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weroha SJ, Oberg AL, Ziegler KL, Dakhilm SR, Rowland KM, Hartmann LC, Moore DF, Jr, Keeney GL, Peethambaram PP, Haluska P. Phase II trial of lapatinib and topotecan (LapTop) in patients with platinum-refractory/resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(1):116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lheureux S, Krieger S, Weber B, Pautier P, Fabbro M, Selle F, Bourgeois H, Petit T, Lortholary A, Plantade A, Briand M, Leconte A, Richard N, Vilquin P, Clarisse B, Blanc-Fournier C, Joly F. Expected benefits of topotecan combined with lapatinib in recurrent ovarian cancer according to biological profile: a phase 2 trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(9):1483–1488. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31826d1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]