Abstract

Background

The number of newly reported psychoactive substances in Europe is now higher than ever. In order to evade legal restrictions, old and novel psychoactive substances from medical research and their derivatives are commonly mislabeled as “not for human consumption” and offered for sale on the Internet and elsewhere. Such substances are widely taken by young people as “club drugs.” Their consumption must be considered in the differential diagnosis of psychiatric, neurological, cardiovascular, or metabolic disturbances of unclear origin in a young patient.

Methods

Selective review of pertinent literature retrieved by a PubMed search, including publications by government-sponsored organizations.

Results

From 2010 to 2012, 163 substances were reported to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), mostly either synthetic cannabinoids (39.3%) or synthetic cathinones (16.6%). Synthetic cannabinoids alter mood and perception; intoxications cause agitation, tachycardia, and arterial hypertension. Synthetic cathinones are hallucinogenic stimulants with predominantly cardiovascular and psychiatric side effects. Severe intoxications cause serotonin syndrome and potentially fatal rhabdomyolysis. Substances in either of these classes often escape detection in screening tests.

Conclusion

Young persons who present with agitation and cardiovascular and/or psychiatric manifestations of unclear origin and whose drug screening tests are negative may be suffering from an intoxication with a novel psychoactive substance. Physicians should know the classes of such substances and their effects. Targeted toxicological analysis can be carried out in a toxicology laboratory or a facility for forensic medicine.

The number of novel psychoactive substances (NPS) in Europe has reached a historic peak. In the European Union’s early warning system, 41 such substances were reported to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) in 2010, 49 in 2011, and 73 in 2012 (1). The more common types were synthetic cannabinoids (39.3%), synthetic cathinones (16.6%), and phenylethylamines (14.1%); piperazines and tryptamines were less common (1). Many NPS are experimental substances from medical research, derivatives of such substances, or previously approved drugs for human consumption. They can be classified by their major effects as sedatives, stimulants, or hallucinogens, or by their chemical structure (e1).

Commerce in these substances occupies a legal gray area (2). In Germany, drugs for human use are regulated on the national level by the Medicinal Products Act (Arzneimittelgesetz, AMG) and the Narcotics Act (Betäubungsmittelgesetz, BtMG). To evade legal restrictions, NPS are mislabeled as “research chemicals,” “herbal incense,” or “bath salts” that are “not for human consumption.” It takes time for the reporting of a new substance to be followed by its characterization, regulation on the European level, and, finally, implementation of Europe-wide regulations by national legislatures; thus, many NPS are not yet covered by the the BtMG (Table 1). The chemical structure of some of them is still unknown. As only individual substances, rather than substance classes, can be prohibited by name under the BtMG, dealers can offer consumers new derivatives of a substance as soon as it has been prohibited. This situation could be improved by amending the BtMG to allow the prohibition of substance classes. Newspaper reports commonly speak of “legal highs,” although the expression “novel psychoactive substances” seems more appropriate for scientific discussion (e2). Users meet in Internet fora to discuss new substances and their dosages, effects, and side effects. The products can be ordered through online webshops and delivered by mail. NPS are easily available and attractively packaged; they appeal to consumers because of their putative legality and wrongly supposed low risk (3).

Table 1. Cannabinones, cathinones, and phenylethylamines listed in the appendices to the German Narcotics Act (BtMG).

| BtMG appendix Substance class | Appendix I (narcotics that must not be sol*1) | Appendix II (narcotics that may be sold but not prescribed*2) | Appendix III (narcotics that may be sold and prescribed*3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| New phenylethylamines/ (synthetic) cathinones | cathinone ephedrone (methcathinone) mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) 4-fluoroamphetamine (4-FA, 4-FMP) dimethoxymethamphetamine (DMMA) |

ethcathinone flephedrone (4-fluormethcathinone, 4-FMC) methedrone (4-methoxymethcathinone, PMMC) 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) 4-methylethcathinone (4-MEC) naphyrone (naphthylpyrovalerone) pyrovalerone butylone methylone (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methcathinone, MDMC) buphedrone 3,4-dimethylmethcathinone (3,4-DMMC) 3-fluoromethcathinone (3-FMC) pentedrone alpha-PVP (alpha-pyrrolidinovalerophenone) 4-methylamphetamine 4-fluoromethamphetamine (4-FMA) p-methoxyethylamphetamine (PMEA) 5-APB, 6-APB ethylphenidate |

lisdexamphetamine |

| (Synthetic) cannabinoids | AM-694, AM-1220, AM-1220 A azepan derivative, AM-2201, AM-2232, AM-2233 CP47, 497 CP47, 497-C6-homologue CP47, 497-C8-homologue CP47, 497-C9-homologue JWH-007, -015, -018, -019, -073, -081, -122, -200, -203, -210, -250, -251, -307, 5-fluoropentyl-JWH-122 RCS-4, RCS-4 ortho-isomer (o-RCS-4) delta-9-THC 1-adamantyl(1-pentyl-1H-indole-3-yl)methanone AKB-48, AKB-48F UR-144 and 5-fluoro-UR-144 |

cannabis dronabinol nabilone |

|

| Piperazine derivatives | 3-trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP) benzylpiperazine (BZP) meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (m-CPP) p-fluorophenylpiperazine (p-FPP) methylbenzylpiperazine (MBZP) |

*1Sale and prescription forbidden. Special permission for scientific purposes can be obtained from the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM).

*2Sale permitted, prescription forbidden.

*3Prescription allowed under the provisions of the Narcotics Prescription Ordinance (Betäubungsmittel-Verschreibungsverordnung, BtMVV).

Up to date as of the 26 th and 27 th amendments to the Narcotics Act, which went into effect on 26 July 2012 and 17 July 2013, respectively

NPS are generally undetectable by immunoassays used for drug screening. Synthetic cannabinoids apparently do not cross-react with the THC test, and synthetic cathinones are not detected by the ELISA-based amphetamine test. Some NPS do, however, cross-react with tests for methamphetamine. Piperazine gives mixed results on the amphetamine test (e3). NPS are generally detected by other means, mainly by specific gas-chromatographic mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid-chromatographic tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Thus, targeted analysis can be carried out in a toxicology laboratory or a forensic medical facility (e3– e5).

For many types of NPS, our current knowledge base is incomplete. Their study is fraught with methodological difficulties; in particular, controlled clinical trials are hard to carry out and only very few have actually been performed. Most of the available data are derived from retro- or prospectively analyzed case series of intoxication and from interviews with drug users, and are thus of limited scientific value. The attribution of particular manifestations to particular substances is often difficult because unidentified substances may be consumed and multiple substances may be taken at once.

The consumption of novel psychoactive substances in Germany

In the MoSyD (Monitoring System for Drug Trends) study, data on the consumption of NPS were collected in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. In 2012, the lifetime prevalence of “spice” consumption stabilized at 7% for persons aged 15 to 18, with a 30-day prevalence of 2% (4). 16% stated that they knew someone who consumed “herbal incense” (4). For other types of NPS, such as “bath salts,” the lifetime prevalence of consumption was found to be 2%, and the 30-day prevalence 1% (4). A number of reports appeared in 2012 about the consumption of “research chemicals” in the party scene and among marginalized youth (4).

Hermanns-Clausen et al. analyzed a series of 50 patients who were seen in an emergency room and reported to the Freiburg Emergency Poison Control Center because of suspected synthetic cannabinoid intoxication, from September 2008 to April 2011 (5).

Moreover, publications from Germany include a case series of persons driving under the influence of synthetic cannabinoids and a case report of withdrawal manifestations and dependency after the consumption of “spice gold” (6, 7).

The actual percentage of users that develop side effects may be underestimated in such studies.

A direct comparison of current figures on the prevalence of substance consumption among adolescents with the reports from Germany leads us to suspect that NPS are, in fact, used much more commonly than the statistics reveal. The reasons for this probably include

a lack of information,

inadequate means of detection,

only rare confirmation by laboratory testing in patients with clinical findings of unclear origin,

and/or the rarity of intoxication compared to consumption.

A learning effect may also be present: once hospital emergency room staff have sufficient personal experience with NPS intoxications, they are less likely to call the Poison Control Center to ask for help with management.

Objectives

In this review, we discuss the pharmacology and clinical effects of the more common classes of NPS in the light of pertinent information from scientific reports and from publications of government-sponsored organizations.

Methods

A selective keyword search was carried out in the PubMed database (Table 2). All abstracts were read and publications with information on the pharmacology, epidemiology, or clinical manifestations of NPS were selected for analysis. The references of these publications were also examined for important sources not revealed by the search. 63 publications were considered informative enough for use in the preparation of this review (Table 2).

Table 2. Keywords and sources.

| Keywords | legal highs, novel psychoactive substances, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones, bath salts, benzylpiperazine, trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine, aminoindane, bromo-dragonfly | |

| Sources | review articles | 18 |

Reports of governmental or government-sponsored organizations, in particular:

|

5 | |

| legal commentary | 1 | |

| analytical and laboratory studies and animal experimentation | 10 | |

| retrospective and prospective clinical studies | 14 | |

| case reports | 11 | |

Synthetic cathinones (“bath salts”)

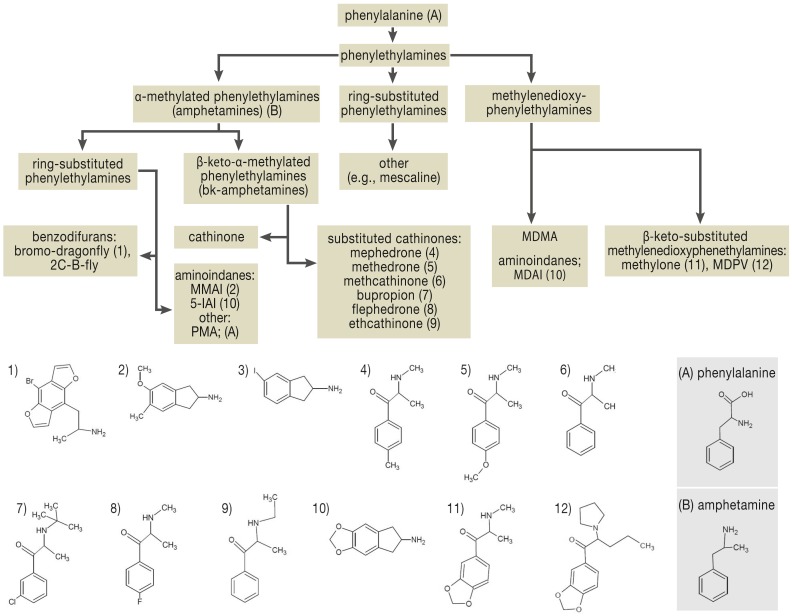

Synthetic cathinone derivatives are bk-amphetamines (β-keto-α-methyl-phenylalkylamines) that are chemically related to methamphetamine (“crystal meth”) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) (Figure 1) (8). Cathinone is found naturally in the khat plant (Catha edulis), which is chewed in Yemen for its stimulant effect (e6). Cathinone derivatives were used as antidepressants in the Soviet Union in the 1930s (9). Methamphetamine was given extensively to German soldiers in the Second World War, under the trade name Pervitin, to counteract fatigue. Pyrovalerone was tested in France and the USA in 1970 for use as a stimulant in patients with chronic fatigue; investigation revealed marked CNS stimulation and accentuation of the subjective need for movement (e7). Synthetic cathinones, particularly mephedrone, are now commonly sold with intentional mislabeling as “bath salts.” They come in the form of white, beige, or brown crystals (10). They are apparently synthesized and packaged in China and/or India for the European market (e8). In an online poll of British clubbers, carried out in 2009, 43% said they had used mephedrone at least once (11). In the USA, consumption figures and the number of calls to Poison Control Centers rose from 2009 to 2011, but began to drop again in 2012 (12, 13). Among twelfth-graders in the USA, the 1-year prevalence of synthetic cathinone consumption was 1.3% in 2012 (e9); the prevalence of consumption of “legal high products” in Germany is similar (2%) (4). The substances most commonly detected in cases of cathinone intoxication are MDPV, pyrovalerone, methylone, pentylone, and alpha-PVP (14).

Figure 1.

Classification of phenylethylamines by chemical structure (modified from Hill SL, Thomas SH) (e23)

“Bath salts” are rapidly absorbed: the “high” is at its most intense 1.5 hours after oral consumption and lasts for 2–8 hours, depending on the substance (15, 16). Synthetic cathinones are potent inhibitors of the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) as well as the reuptake transporters for dopamine (DAT) and norepinephrine (NAT) (e10). Selectivity varies from one substance to another (e10). These substances can be classified in three groups (e11):

cocaine-MDMA mixed type (mephedrone, methylone, ethylone, butylone, and naphyrone): nonspecific monoamine reuptake inhibition with about five times more DAT than SERT inhibition. All except naphyrone also promote serotonin release. Mephedrone promotes dopamine release.

methamphetamine-like type (cathinone, flephedrone, and methcathinone): these substances inhibit dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake and promote dopamine release.

pyrovalerone type (pyrovalerone, MDPV): selective inhibition of catecholamine reuptake. Does not promote the release of monoamines.

Flephedrone, mephedrone, and methcathinone are also 5HT2A agonists. The blood–brain barrier is highly permeable to mephedrone and MDPV in particular (e10). These substances are metabolized through the activity of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes or catechol-O-methyltransferase and are excreted either by the kidneys or by the biliary system (e4).

Users of synthetic cathinones report euphoria, increased drive, loquacity, a subjective need to move and act, lightening of mood, diminished hostility, clear thinking, sexual stimulation, and heightened perception of music (11, 16). Doses ranging from 5 to 20 mg are taken, usually orally but also intranasally, rectally, and intravenously (16). Drugs in this group induce a strong desire for further doses: 80% of users surveyed said that they had taken more mephedrone than they had originally planned, and 45% said they had used up their personal supply of the drug (17). There have been individual case reports of users who gave themselves more than 10 intravenous doses one after the other (18). The adverse effects of synthetic cathinones are cardiovascular, neurological, and psychiatric (Box 1) (13, 14, 19, e12); the main ones are tachycardia, arterial hypertension, hallucinations, and agitation (20). Users are particularly disturbed by an unpleasant bodily odor that is characteristic of mephedrone use (21). Rare complications include syncope, ST-segment changes, and myocarditis (22).

Box 1. Adverse effects of, and signs of intoxication with, synthetic cathinones*.

-

cardiovascular

tachycardia (22–56%)

arterial hypertension (4–25%)

palpitations (11–28%)

chest pain (6–28%)

dyspnea (8–11%)

vasoconstriction (6–8%)

ECG changes (2%)

arrhythmia

myocardial infarction

myocarditis

vST-segment changes

syncope

-

neurological

headache (5–17%)

mydriasis (7–13%)

l- ight-headedness (8–12%)

paresthesia (4%)

seizures (2–4%)

dystonic movements (2%)

tremor (2%)

amnesia

dysgeusia

cerebral edema

motor automatisms

muscle spasm

nystagmus

parkinsonism

stroke

-

psychiatric

agitation (50–82%)

aggression (57%)

hallucinations (27–40%)

confusion (14–34%)

anxiety(15–17%)

insomnia (4%)

catatonia (1%)

anhedonia

anorexia

depression

increased libido

injurious behavior

panic attacks

self-injurious behavior

suicidality

psychosis

-

metabolic

hyponatremia

hypokalemia (4%)

acidosis (1%)

-

gastrointestinal

nausea/vomiting (5–22%)

abdominal pain (2–5%)

-

renal

elevated creatinine level (1–5%)

acute renal failure

-

pulmonary

hyperventilation/tachypnea (7%)

dyspnea (8–11%)

-

muscular

CK elevation (3–20%)

rhabdomyolysis (6%)

compartment syndrome

-

cutaneous

rash (6–7%)

-

other

fever (9–11%)

abnormal liver function tests (2%)

abscesses, bruxism

diaphoresis

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

hyperthermia

urinary disturbances

necrotizing fasciitis

spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema

unpleasant body odor (mephedrone)

soft-tissue injury

The psychotic manifestations of synthetic cathinone use often consist of paranoia with auditory and visual hallucinations (23), which can persist for up to four weeks and take a more severe course than with other amphetamines (23, 24). In most cases of intoxication with psychotic symptoms, MDPV is the cause (13).

Intoxication can manifest itself clinically with sympathomimetic effects, delirium, or the serotonin syndrome. The patients develop aggressiveness, psychotic manifestations, fever up to 41.5 °C, and/or arterial hypertension (21, 24), and they may have metabolic acidosis, an elevated creatine kinase (CK) level, and muscle damage ranging to rhabdomyolysis (21, 24). The simultaneous appearance of hyperthermia and rhabdomyolysis in MDMA intoxication has been reported and attributed to decoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (e13). In very severe cases, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) can arise, leading to potentially fatal multi-organ failure. From September 2009 to October 2011, there were 128 documented deaths associated with mephedrone use in the United Kingdom: of the 62 cases that could be assessed further, death was due to the acute toxicity of the drug itself in 26, and to self-destructive or suicidal behavior in 18 (25). In case reports of deaths in 2011 and 2012, other synthetic cathinones play a larger role, such as MDPV, butylone, and methedrone (e11).

Synthetic cannabinoids (“spice”)

“Spice” appeared in Europe in 2005, accompanied by the claim that its psychotropic effect was induced purely by natural, botanical components (26). The real active substance was discovered in 2009 with the detection of undeclared synthetic cannabinoid receptor (CB) agonists by Volker Auwärter and colleagues at the University of Freiburg (Germany) (27).

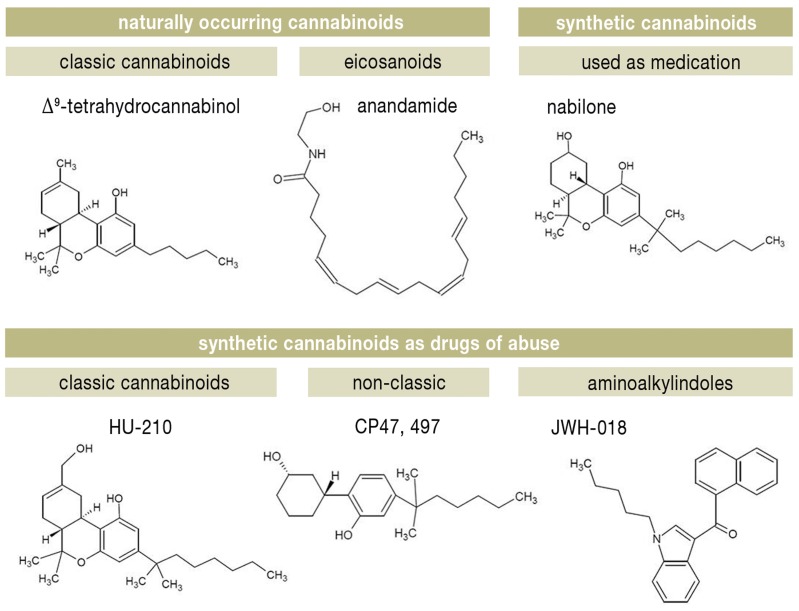

CB agonists are classified according to their chemical structure, as follows (28) (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Classification of cannabinoids

classic cannabinoids, such as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) from the cannabis plant (Cannabis sativa), the approved anti-emetic nabilone, and HU cannabinoids, which closely resemble THC.

non-classic cannabinoids, such as the cyclohexylphenol (CP) cannabinoids.

aminoalkylindoles: the JWH series, synthesized by the chemist J. W. Huffmann, contains many CB ligands.

eicosanoids, such as the endocannabinoid anandamide.

These substances are sold as “herbal incense” supposedly derived from plants, and the consumers smoke them. The synthetic cannabinoids are sprayed onto pharmacologically inactive vegetable matter accounting for most of the bulk of “spice” by weight. The ingredients listed on the package are generally incomplete or false. One gram of “spice” contains 77.5 to 202 mg of synthetic cannabinoid, with high variability from one package to another (29, 30). Consumers do not know what active substance they are using, or in what dose. Further ingredients include the β2-mimetic substance clenbuterol, which may be responsible for the sympathomimetic manifestations of “spice” intoxication (tachycardia, hypokalemia), and large amounts of tocopherol (vitamin E), possibly added in order to prevent detection (27).

Research on the cannabinoid system has revealed several hundred agonists that might be abused, with varying affinity for the CB1 und CB2 receptors (3). The endocannabinoid system participates in the regulation of physiological processes such as caloric balance and the control of arterial smooth muscle tone (e14, e15). CB1 receptors are found mainly in the nervous system and CB2 receptors mainly in the spleen, the tonsils, and cells of the immune system, as well as on particular types of neurons (28). Synthetic cannabinoids are potent CB1 agonists: the affinity of JWH018 for the CB1 receptor is five times as high as that of THC, while that of AM-694 is 500 times as high (e16, e17). Users report that “spice” has a stronger psychotropic effect than marijuana (31).

Synthetic cannabinoids exert a THC-like effect, with alterations of mood, perception, sleep and wakefulness, body temperature, and cardiovascular function (5). Their side effects are more varied and more severe than those of THC, with the more common ones being tachycardia, arterial hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hallucinations, and agitation (Box 2) (5, 28, e18, e19). Chest pain, myocardial ischemia, and psychosis are rarer (7, 32). As the “spice” sold at any particular time may contain new cannabinoids, previously unrecognized side effects may arise. In the USA, for example, widespread use of the fluoridated synthetic cannabinoid XLR-11 was associated with a series of cases of acute renal failure in young users in late 2012 (26). Synthetic cannabinoids can cause dependency (7, 32). Very few deaths attributable to the consumption of synthetic cannabinoids have been reported to date: there has been one case of fatal coronary ischemia, as well as one of suicide in a user who became depressed after consuming a cannabinoid substance (3).

Box 2. Adverse effects of, and signs of intoxication with, synthetic cannabinoids*.

-

cardiovascular

tachycardia (37–76%)

arterial hypertension (10–34%)

ECG changes (2–14%)

chest pain (7–10%)

hypotension (2–7%)

syncope (3–4%)

bradycardia (2–3%)

cardiac ischemia

-

neurological

dizziness (9–24%)

loss of consciousness (2–17%)

somnolence (17–19%)

anesthesia/paresthesia (2–10%)

muscle cramps/fasciculations (7%)

seizures (3–4%)

headache (3%)

ataxia (2%)

tremor (4%)

irritability

-

psychiatric

agitation (19–41%)

hallucinations (11–38%)

anxiety/panic attacks (21%)

confusion (9–14%)

anterograde amnesia (7%)

psychosis (3%)

aggressive behavior (3%)

delusions

-

metabolic

hyperglycemia (31%)

hypokalemia (28%)

other electrolyte changes (2%)

-

gastrointestinal

nausea/vomiting (9–28%)

-

renal

renal failure

-

pulmonary

dyspnea (5%)

hyperventilation (2–4%)

-

muscular

CK elevation (14%)

myalgia (7%)

-

cutaneous

xerostomia (14%)

diaphoresis (4%)

pallor (1%)

photosensitivity

-

ocular

mydriasis (3–38%)

conjunctival hyperemia (14%)

-

other

fever (2%)

hyperthermia

*modified from (5, 28, e18, e19)

Other NPS (“research chemicals”)

Piperazine derivatives

Piperazine is an anthelminthic drug that is structurally related to various other classes of drugs, including antidepressants (e.g., trazodone), atypical neuroleptic drugs (e.g., olanzapine), and antihistamines (e.g., cetirizine). Psychoactive piperazine derivatives such as 1-benzylpiperazine (BZP) and trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP) have been drugs of abuse since about the year 2000 (33). They are often taken orally in multi-substance combinations. Piperazine derivatives stimulate the release of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin and inhibit monoamine reuptake (34). Exceptionally for psychoactive substances, BZP and TFMPP have been studied in controlled trials. The manifestations of intoxication are typical for stimulants (eTable 1). A study of the effects of combined BZB, TFMPP, and alcohol consumption was terminated because of serious adverse effects—arterial hypertension, tachycardia, agitation, anxiety, hallucinations, vomiting, insomnia, and migraine (35). The manifestations depend on the plasma concentration of the drug: concentrations between 0 and 0.5 mg/L are associated with anxiety, vomiting, and palpitations, concentrations above 0.5 mg/L with agitation and confusion. Seizures may occur with plasma concentrations as low as 0.05 mg/L but regularly accompany concentrations above 2.15 mg/L (36).

eTable. Summary of characteristics of novel psychoactive substances.

| Synthetic cathinones | Substances | mephedrone, methylone, ethylone, butylone, naphyrone, methcathinone, flephedrone, MDPV, α-PVP, pyrovalerone, etc. |

| Colloquial names | bath salts, meow meow (mephedrone), ivory wave, vanilla sky, cloud 9, lunar wave, others | |

| Usual dose | 5–20 mg | |

| Mechanism of action | monoamine reuptake inhibitors (DAT, NAT, SERT), dopamine/serotonin receptor agonists, serotonin/dopamine release by DAT and SERT | |

| Effects | euphoria, excitement, intensified perception of music, brightening of mood, reduction of hostility, clear thinking, mild sexual stimulation | |

| Side effects | cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension, vasoconstriction, hyperthermia neurological: mydriasis psychiatric: hallucinations, anorexia, depression, insomnia, craving, anxiety, panic attacks |

|

| Intoxication | cardiovascular: myocardial infarction, circulatory failure neurological: seizures, cerebral edema, stroke psychiatric: psychosis, violent behavior, autoaggressive behavior, suicide attempt other: respiratory depression, muscle cramps, serotonin syndrome |

|

| Sources: 15–25, e10–e12 | ||

| Synthetic cannabinoids | Substances | AM-694, -1220, -1220 azepan derivative, -2201, -2232, -2233. CP47, 497, JWH-007, -015, -018, -019, -073, -081, -122, -200, -203, -210, -250, -251, -307, 5-fluoropentyl-JWH-122, RCS-4, o-RCS-4, AKB-48, AKB-48F, UR-144, 5-fluoro-UR-144 (XLR-11), etc. |

| Colloquial names | spice K2, K2-blonde, spice diamond, spice gold, arctic spice, genie, zombie 2010, black box, smoke’n’skulls, others | |

| Usual dose | 1 package (usually 3 g) = 8 joints | |

| Mechanism of action | CB1 receptor agonist | |

| Effects | increased empathy, feeling of well-being, euphoria, disinhibition, loquacity, hunger | |

| Side effects | cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension neurological: dizziness, mydriasis psychiatric: agitation, hallucinations other: nausea/vomiting, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia |

|

| Intoxication | psychosis, seizures, sympathomimetic effects | |

| Sources: 3, 5, 7, 26–32, e16–e19 | ||

| Piperazinederivates | Substances | benzylpiperazine (BZP), trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP), etc. |

| Colloquial names | nemesis, jax, A2, Benny Bear, flying angel, legal E or legal X, pep X, others | |

| Usual dose | 300 mg BZP, 75 mg TFMPP | |

| Mechanism of action | sympathomimetic stimulation; BZP, dopaminergic and noradrenergic; TFMPP, serotoninergic | |

| Effects | increased self-confidence, euphoria, intensified emotion | |

| Side effects | cardiovascular: palpitations, tachycardia, arterial hypertension neurological: migraine psychiatric: agitation, anxiety, hallucinations, vomiting, insomnia, dysphoria other: diminished appetite |

|

| Intoxication | cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension, QT prolongation abdominal: nausea, epigastric pain neurological: headache, tremor psychiatric: confusion, insomnia, intrusive thoughts, mood swings, irritability other: sympathomimetic effects |

|

| Sources: 33–36, e22 | ||

| Phenylethylamines | Substances | aminoindanes: 5-iodo-2-aminoindane (5-IAI); 5-methoxy-6-methyl-2-aminoindane (MMAI); 5,6-methylenedioxy-2-aminoindane (MDAI) |

| Colloquial names | woof woof, sparkle, mindy, others | |

| Usual dose | 70–300 mg MDAI | |

| Mechanism of action | MDMA analogue, monoamine reuptake inhibitor, promotes 5HT release | |

| Effects | hallucinations, psychomotor activation | |

| Side effects | cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension, arterial hypotension neurological: allodynia, hypalgesia, dizziness, nystagmus, mydriasis, increased muscle tone other: hyperthermia, worsened vision and hearing, hyperventilation, vomiting |

|

| Intoxication | neurological: seizures muscular: rhabdomyolysis other: sympathomimetic effects, serotonin syndrome |

|

| Substances | 1-(8-bromobenzo[1,2-b;4,5-b’]difuran-4-yl)-2-aminopropane | |

| Colloquial names | bromo-dragonfly | |

| Usual dose | 200–800 µg | |

| Mechanism of action | 5HT1-, 5HT2-, and α1-agonist | |

| Effects | potent, long-acting hallucinogen | |

| Side effects | neurological: seizures pulmonary: respiratory problems cardiovascular: vasospasm other:multi-organ failure, gangrene |

|

Aminoindanes

MDAI (5,6-methylenedioxy-2-aminoindane), 5-IAI (5-iodo-2-aminoindane), and MMAI (5-methoxy-6-methyl-2-aminoindane) have a so-called entactogenic effect (i.e., they intensify the perception of one’s own emotions) and are therefore marketed as “legal” alternatives to MDMA (37). These drugs are weak inhibitors of monoamine reuptake, but they powerfully stimulate the release of non-vesicular serotonin. 5-IAI and MDAI became more widespread around the time that mephedrone was forbidden. Its desired effects are mild euphoria, distorted spatial and temporal perception, intense color perception, and the sense that one has a better understanding of other persons’ emotions. The effect commences as soon as 10 minutes after oral consumption of the drug, lasts an hour, and then comes gradually to an end. The undesired effects are of a cardiovascular, neurological, or psychiatric nature (eTable 1). The scientific literature contains very little information about the potential toxicity of 2-aminoindane derivatives. In animal studies, a dose 40 times higher than a behavior-changing dose had no toxic effects (including neurotoxic ones). Yet these are by no means harmless substances: among human users, there have been reported cases of hyperthermia, serotonin syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, and death (37, 38, e20).

“Bromo-dragonfly”

“Bromo-dragonfly” ([R]-1-[4-bromofuro(2,3-f)[1]benzofuran-8-yl]propane-2-amine) is a substituted phenylethylamine with a similar hallucinogenic effect to that of LSD (39). It is a potent agonist of 5-HT1, 5-HT2A, and α1receptors. Its latency of effect is up to six hours; the effect (visual and auditory hallucinations, a feeling of well-being and solidarity) can last as long as three days (39). The amount of active substance varies markedly from one batch to another, so that reliable dosing is impossible and there is a danger of overdose (e21). “Bromo-dragonfly” is highly toxic: it can cause seizures, acidosis, pulmonary edema, and prolonged vasospasm leading to gangrene and multiple organ failure (39, 40). Deaths have been reported, and there has also been a reported case of uncontrollable vasospasm despite maximal vasodilatory treatment, leading to the amputation of multiple fingers (39, 40).

Overview

Today’s psychoactive substance users can choose among various stimulants, hallucinogens, and sedatives with a mouse-click (eTable 1). Some of these substances are prohibited by the German Narcotics Act, but many are too new to be covered by it. The substances in circulation change frequently, but their effects and toxicities tend to remain the same; different groups of substances have typical profiles (eTable 1), which, however, overlap. Stimulants, in particular, can cause sympathomimetic manifestations or a serotonin syndrome. If standard drug screening is negative in such a situation, an intoxication with a new psychotropic substance should be suspected. The diagnosis can be established by analysis in a specialized laboratory, e.g., a toxicology laboratory or a forensic medical facility.

Key Messages.

163 novel psychoactive substances of abuse were reported to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction in the period 2010–2012.

These substances belong to the chemical groups of synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones, phenylethylamines, tryptamines, and piperazines and are often undetectable by standard drug screening tests.

Synthetic cannabinoids are CB1 receptor agonists. Compared to THC, they are more potent and longer-acting and have much worse adverse effects.

Synthetic cathinones are bk-amphetamines with both stimulant and hallucinogenic effects. They may cause severe intoxication.

Young persons who present with psychiatric, metabolic, and/or cardiovascular manifestations of unclear origin and whose drug screening tests are negative may be suffering from an intoxication with a novel psychoactive substance.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that no conflict of interests exists.

References

- 1.Europäische Beobachtungsstelle für Drogen und Drogensucht Europäischer Drogenbericht 2013. Trends und Entwicklungen. Luxemburg: Amt für Veröffentlichungen der Europäischen Union; 2013. Drogenangebot in Europa; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nobis. NStZ. 2012. „LegaI-High”-Produkte - wirklich illegal? - Oder: Wie ein Aufsatz sich verselbstständigt! 422 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fattore L, Fratta W, Beyond THC. The New Generation of Cannabinoid Designer Drugs. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhard C, Werse B, Schell-Mack C. Jahresbericht MoSyD. Drogentrends in Frankfurt am Main 2012. Centre for Drug Research. 201 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermanns-Clausen M, Kneisel S, Szabo B, Auwärter V. Acute toxicity due to the confirmed consumption of synthetic cannabinoids: clinical and laboratory findings. Addiction. 2013;108:534–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musshoff F, Madea B, Kernbach-Wighton G, et al. Driving under the influence of synthetic cannabinoids („Spice“): a case series. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann US, Winkelmann PR, Pilhatsch M, Nees JA, Spanagel R, Schulz K. Withdrawal phenomena and dependence syndrome after the consumption of „spice gold“. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:464–467. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glennon RA, Yousif M, Naiman N, Kalix P. Methcathinone: a new and potent amphetamine-like agent. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1987;26:547–551. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly JP. Cathinone derivatives: a review of their chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Drug Test Anal. 2011;3:439–453. doi: 10.1002/dta.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karila L, Reynaud M. GHB and synthetic cathinones: clinical effects and potential consequences. Drug Test Anal. 2011;3:552–559. doi: 10.1002/dta.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winstock A, Mitcheson L, Ramsey J, Davies S, Puchnarewicz M, Marsden J. Mephedrone: use, subjective effects and health risks. Addiction. 2011;106:1991–1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood KE. Exposure to bath salts and synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol from 2009 to 2012 in the United States. J Pediatr. 2013;163:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of „bath salts“ and „legal highs“ (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol. 2011;49:499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marinetti LJ, Antonides HM. Analysis of synthetic cathinones commonly found in bath salts in human performance and postmortem toxicology: method development, drug distribution and Interpretation of Results. J Anal Toxicol. 2013;37:135–146. doi: 10.1093/jat/bks136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schifano F, Albanese A, Fergus S, et al. Psychonaut Web Mapping, ReDNet Research Groups. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone; ’meow meow’): chemical, pharmacological and clinical issues. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross EA, Watson M, Goldberger B. „Bath salts“ intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:967–968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1107097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman TP, Morgan CJ, Vaughn-Jones J, Hussain N, Karimi K, Curran HV. Cognitive and subjective effects of mephedrone and factors influencing use of a ’new legal high’. Addiction. 2012;107:792–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belton P, Sharngoe T, Maguire FM, Polhemus M. Cardiac infection and sepsis in 3 intravenous bath salts drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:e102–e104. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood DM, Davies S, Greene SL, et al. Case series of individuals with analytically confirmed acute mephedrone toxicity. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:924–927. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.531021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy CM, Dulaney AR, Beuhler MC, Kacinko S. „Bath salts“ and „plant food“ products: the experience of one regional US poison center. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:42–48. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penders TM, Gestring RE, Vilensky DA. Excited delirium following use of synthetic cathinones (bath salts) Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson PJ, Quinn MJ, Dodd JD. Headshop heartache: acute mephedrone ’meow’ myocarditis. Heart. 2010;96:2051–2052. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.209338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loeffler G, Penn A, Ledden B. „Bath salt“-induced agitated paranoia: a case series. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73 doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borek HA, Holstege CP. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of „bath salts“ containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schifano F, Corkery J, Ghodse AH. Suspected and confirmed fatalities associated with mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone, „meow meow“) in the United Kingdom. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:710–714. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318266c70c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use-multiple states 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auwärter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Müller M, Pütz M, Ferreirós N. ’Spice’ and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? J Mass Spectrom. 2009;44:832–837. doi: 10.1002/jms.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seely KA, Prather PL, James LP, Moran JH. Marijuana-based drugs: innovative therapeutics or designer drugs of abuse? Mol Interv. 2011;11:36–51. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simolka K, Lindigkeit R, Schiebel HM, Papke U, Ernst L, Beuerle T. Analysis of synthetic cannabinoids in „spice-like“ herbal highs: snapshot of the German market in summer 2011. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hillebrand J, Olszewski D, Sedefov R. Legal highs on the internet. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:330–340. doi: 10.3109/10826080903443628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths P, Sedefov R, Gallegos A, Lopez D. How globalization and market innovation challenge how we think about and respond to drug use: ’Spice’ a case study. Addiction. 2010;105:951–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller H, Sperling W, Köhrmann M, Huttner HB, Kornhuber J, Maler JM. The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes. Schizophr Res. 2010;118:309–310. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Boer D, Bosman IJ, Hidvegi E, et al. Piperazine-like compounds: a new group of designer drugs-of-abuse on the European market. For Sci Int. 2001;121:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elliott S. Current awareness of piperazines: pharmacology and toxicology. Drug Test Anal. 2011;3:430–438. doi: 10.1002/dta.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson I, Williams G, Caldwell B, et al. Randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the effects of the ’party pills’ BZP/TFMPP alone and in combination with alcohol. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1299–1308. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gee P, Gilbert M, Richardson S, Moore G, Paterson S, Graham P. Toxicity from the recreational use of 1-benzylpiperazine. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46:802–807. doi: 10.1080/15563650802307602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coppola M, Mondola R. 5-iodo-2-aminoindan (5-IAI): chemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of a research chemical producing MDMA-like effects. Toxicol Lett. 2013;218:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sainsbury PD, Kicman AT, Archer RP, King LA, Braithwaite RA. Aminoindanes-the next wave of ’legal highs’? Drug Test Anal. 2011;3:479–482. doi: 10.1002/dta.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corazza O, Schifano F, Farre M, et al. Designer drugs on the internet: a phenomenon out-of-control? The emergence of hallucinogenic drug Bromo-Dragonfly. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6:125–129. doi: 10.2174/157488411796151129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorlacius K, Borna C, Personne M. Bromo-dragon fly—life-threatening drug. Can cause tissue necrosis as demonstrated by the first described case. Lakartidningen. 2008;105:1199–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Carroll FI, Lewin AH, Mascarella SW, Seltzman HH, Reddy PA. Designer drugs: a medicinal chemistry perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Corazza O, Demetrovics Z, van den Brink W, Schifano F. ’Legal highs’ an inappropriate term for ’Novel Psychoactive Drugs’ in drug prevention and scientific debate. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24:82–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Rosenbaum CD, Carreiro SP, Babu KM. Here today, gone tomorrow…and back again? A review of herbal marijuana alternatives (K2, Spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), kratom, Salvia divinorum, methoxetamine, and piperazines. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:15–32. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0202-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Meyer MR, Wilhelm J, Peters FT, Maurer HH. Beta-keto amphetamines: studies on the metabolism of the designer drug mephedrone and toxicological detection of mephedrone, butylone, and methylone in urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:1225–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Kneisel S, Auwärter V, Kempf J. Analysis of 30 synthetic cannabinoids in oral fluid using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Test Anal. 2013;5:657–669. doi: 10.1002/dta.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Graziani M, Milella MS, Nencini P. Khat chewing from the pharmacological point of view: an update. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:762–783. doi: 10.1080/10826080701738992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Goldberg J, Gardos G, Cole JO. A controlled evaluation of pyrovalerone in chronically fatigued volunteers. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1973;8:60–69. doi: 10.1159/000467975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Baron M, Elie M, Elie L. An analysis of legal highs: do they contain what it says on the tin? Drug Test Anal. 2011;3:576–581. doi: 10.1002/dta.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Maxwell JC. Psychoactive substances-Some new, some old: A scan of the situation in the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.011. [in Press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, et al. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:458–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Zawilska JB, Wojcieszak J. Designer cathinones-an emerging class of novel recreational drugs. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;231:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.James D, Adams RD, Spears R, et al. Clinical characteristics of mephedrone toxicity reported to the U.K. National Poisons Information Service. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:686–689. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.096636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Nakagawa Y, Suzuki T, Tayama S, Ishii H, Ogata A. Cytotoxic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-alkylamphetamines, MDMA and its analogues, on isolated rat hepatocytes. Arch Toxicol. 2009;83:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Di Marzo V, Matias I. Endocannabinoid control of food intake and energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:585–589. doi: 10.1038/nn1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Randall MD, Kendall DA, O’Sullivan S. The complexities of the cardiovascular actions of cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:20–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Atwood BK, Huffman J, Straiker A, Mackie K. JWH018, a common constituent of ’Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB receptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:585–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Psychoyos D, Vinod KY. Marijuana, Spice ’herbal high’, and early neural development: implications for rescheduling and legalization. Drug Test Anal. 2013;5:27–45. doi: 10.1002/dta.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Forrester MB. Synthetic cathinone exposures reported to Texas poison centers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:609–615. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.677890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Gunderson EW, Haughey HM, Ait-Daoud N, Joshi AS, Hart CL. „Spice“ and „K2“ herbal highs: a case series and systematic review of the clinical effects and biopsychosocial implications of synthetic cannabinoid use in humans. Am J Addict. 2012;21:320–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Corkery JM, Elliott S, Schifano F, Corazza O, Ghodse AH. MDAI (5,6-methylenedioxy-2-aminoindane; 6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[f][1,3]benzodioxol-6-amine; ’sparkle’; ’mindy’) toxicity: a brief overview and update. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:345–355. doi: 10.1002/hup.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Psychonaut Web Mapping Group. London UK: Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London; 2009. Bromo-Dragonfly Report. [Google Scholar]

- e22.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Details for Piperazines. www.unodc.org/LSS/SubstanceGroup/Details/8242b801-355c-4454-9fdc-ba4b7e7689d5#_ftn11. (last accessed on 4 December 2013)

- e23.Hill SL, Thomas SH. Clinical toxicology of newer recreational drugs. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:705–719. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.615318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]