Abstract

The ability to determine polymer elasticity and force-extension relations from polymer dynamics in flow has been challenging, mainly due to difficulties in relating equilibrium properties such as free energy to far-from-equilibrium processes. In this work, we determine polymer elasticity from the dynamic properties of polymer chains in fluid flow using recent advances in statistical mechanics. In this way, we obtain the force-extension relation for DNA from single molecule measurements of polymer dynamics in flow without the need for optical tweezers or bead tethers. We further employ simulations to demonstrate the practicality and applicability of this approach to the dynamics of complex fluids. We investigate the effects of flow type on this analysis method, and we develop scaling laws to relate the work relation to bulk polymer viscometric functions. Taken together, our results show that nonequilibrium work relations can play a key role in the analysis of soft material dynamics.

1 Introduction

In recent years, polymeric materials have been studied using single molecule techniques such as atomic force microscopy, optical traps, magnetic tweezers, and fluorescence microscopy.1–3 Single molecule force spectroscopy allows for direct determination of the elastic force-extension relationships for single proteins or polymers by applying external forces to surface-tethered macromolecules.1 In addition, these methods can be used to study the molecular response and corresponding forces during the relaxation of stretched polymers to a coiled state.4 However, these high-precision approaches require active probes, complex instrumentation, and generally involve measurements that are performed in the absence of fluid flow.

Alternatively, polymer chains can be stretched and oriented far from equilibrium using hydrodynamic flow,5–7 and well-defined fluid flows are easily generated in microfluidic devices.8–10 In this way, coupling single molecule fluorescence microscopy with microfluidics allows for direct observation of polymer dynamics in equilibrium and nonequilibrium conditions. Single molecule fluorescence microscopy has been used to study the diffusion of dye-labeled polymers in free solution,11 polymer dynamics under strong confinement,3 and chain stretching in hydrodynamic flows.2,8

Single polymer experiments have been complemented with computer simulations to provide a particularly powerful approach to study polymer rheology.12 In this way, equilibrium force-extension relations for single polymer chains are generally taken to be ingredients (or given functions) for stochastic simulation methods for polymers such as Brownian dynamics (BD). In an alternative approach, Monte Carlo simulations based on the GENERIC formalism have been used to determine the nonequilibrium free energy and elasticity for polymer chains in flow.13,14 Nevertheless, development of new methods to determine equilibrium materials properties such as polymer elasticity from nonequilibrium flow dynamics, and in particular, methods that can be interfaced with single molecule experiments and BD simulations, is critically required.

Extracting equilibrium materials properties from nonequilibrium polymer dynamics in flow is challenging because hydrodynamic flow results in an energetically dissipative process, which complicates free energy calculations. Recent advances in nonequilibrium statistical mechanics via the Jarzynski equality (JE) have enabled determination of free energy changes from nonequilibrium quantities such as work and heat.15–17 In this article, we apply nonequilibrium work relations to polymeric materials driven by external fluid flows, which are dynamic processes governed by dissipative forces. Using this approach, we show that it is possible to determine polymer elasticity from dynamic stretching trajectories of polymer molecules in flow.

The Jarzynski equality allows the free energy change between two states to be determined from nonequilibrium work distributions acquired from repeated experiments for an arbitrary process:15

| (1) |

where ΔF is the free energy change, w is the work, and β = 1/kBT is the inverse Boltzmann temperature. Remarkably, the JE is valid for arbitrary processes far from equilibrium, regardless of the rate of the process. Initially, the JE was derived to determine the free energy change ΔF between two equilibrium states. However, it has been shown that the JE is valid for considering nonequilibrium steady states and nonequilibrated states under certain conditions.18–20

Over the past few years, nonequilibrium work relations have been applied to a wide array of processes in molecular biophysics, mainly using force spectroscopy via optical tweezers.17,21–23 Previous experimental21,22 and computational17 studies in this area have focused on the determination of free energy landscapes of biological macromolecules (e.g. proteins or RNA & DNA hairpins over submicron length scales) from force-extension measurements. Importantly, additional studies have assessed the validity of fluctuation theorems in the presence of dissipative forces.24–26

In this work, we apply nonequilibrium work relations to determine materials properties such as elasticity from polymer dynamics in fluid flows using a combination of simulations and analysis of experimental stretching trajectories obtained from single molecule fluorescence microscopy, without the need for bead-tethered probes or optical tweezers. First, we present and establish the valid work expression for analyzing polymeric materials driven by flow. We then show that elastic free energy and force-extension relationships can be determined from the work done in hydrodynamically-driven, far from equilibrium processes over micron length scales. Importantly, these results are shown using both BD simulations of polymer chains and experimental stretching trajectories from single polymer dynamics. Finally, the present study mainly focuses on polymer dynamics in vorticity-free flows without intramolecular hydrodynamic interactions. In a recent follow-up study, we show in detail that this framework can be generalized to fluid flows with vorticity and under conditions in which intramolecular hydrodynamic interactions are important for determining polymer dynamics.27

2 Methods

2.1 Brownian dynamics simulations

We used Brownian dynamics simulations of coarse-grained bead-spring or bead-rod polymer chains in a variety of flow fields.28–30 Polymer chains are modeled as coarse-grained bead-spring chains, wherein each sub-portion of a polymer chain is modeled as a bead, or center of hydrodynamic drag, connected by N springs that represent the entropic elasticity of a polymer. The contour length L of the polymer is given by L = NK,sN bK, where NK,s is the number of Kuhn steps per spring, N is the number of springs, and bK is the Kuhn step size. In this model, the number of beads in the bead-spring chain is Nb = N +1.

Using this approach, a force balance on the polymer chain leads to the stochastic differential equation:28

| (2) |

where u is the local unperturbed fluid velocity and xk are bead positions (corresponding to segments of the polymer chain). In Equation (2), the non-hydrodynamic and non-Brownian forces are given by F = Fspr, which is the net entropic spring force on a bead. The spring force is given by Fspr = ∇U, where U is the potential energy given by the entropic elasticity and defined below. In this work, we consider a dumbbell model (Nb = 2) and multi-bead-spring models (Nb = 6, 10, 20, see Supplementary Information†). In addition, D = B · BT is the diffusion tensor, and B is the tensor of weighting factors. Furthermore, B can be determined by a Cholesky decomposition of the diffusion tensor D, and the magnitude of the Brownian term including B is chosen to satisfy the fluctuation-dissipation theorem.28 In this way, dW is a Wiener process and is chosen from a real-valued Gaussian distribution of mean 0 and variance dt. For a semiflexible polymer chain modeled as a single-mode dumbbell, the potential energy is given by the Marko-Siggia force expression:31

| (3) |

where lp = bK/2 is the persistence length and the fractional extension of the spring is given by z = |x2 − x1|/L. The potential energy U in Equation (3) can be obtained by integrating the scalar Marko-Siggia force relation given as:

| (4) |

with respect to position z. In addition, using Cohen’s Padé approximant to the inverse Langevin force relation given as:32

| (5) |

we can perform a similar integration to determine U for flexible polymer chains such as polystyrene.

The definition of the rate of work ẇ done on the polymer chain by the action of an imposed external flow is given by:33

| (6) |

where Uk is the net potential energy experienced by bead k. The rate of work is the material (or convective) derivative of U, which describes the time rate of change of the potential energy in the Lagrangian viewpoint, analogous to the transport of momentum in fluid motion given by the Navier-Stokes equation,34. The work w performed by the flow is given by the time integral of Equation (6), such that w = ∫ ẇ dt. In this article, we also show that this work definition is the valid expression for applying the equilibrium statement of JE to polymeric materials driven by flow (see Results and Discussion).

2.2 Algorithm

Nonequilibrium trajectories of polymer conformations in flow were simulated by a highly efficient semi-implicit predictor-corrector algorithm.29 We render Equations (2) and (6) dimensionless and recast them in terms of the end-to-end vector Qk for spring k such that:

| (7) |

where Qk = xk+1 − xk, is the bead Peclét number which is a dimensionless measure of the applied flow strength, ε̇ is the applied fluid strain rate, ζ = 6πηsa is the Stokes drag coefficient on each bead, where ηs is the solvent viscosity and a is the bead radius. In addition, κim = δi1δm1 − δi2δm2 is the dimensionless velocity gradient tensor for a planar extensional flow. In this work, we consider free-draining chains such that the dimensional form of D = kBTI/ζ, where I is the unit tensor. In this way, D is a constant isotropic tensor. In a follow-up study, we have used alternative expressions for D to account for fluctuating hydrodynamic interactions, wherein D is generally anisotropic and accounts for chain dynamics under non-free draining conditions.27 Furthermore, to render Equations (2) and (6) dimensionless, we used as the length scale, as the time scale, Es = kBT as the energy scale, and Fs = Es/ls as the force scale. Finally, using Equation (7) at each time step, an updated value of Qk is computed by employing a semi-implicit predictor-corrector method.27,29

For a single-mode dumbbell model of a polymer, the simulation procedure is as follows. First, we use the additional subscripts t or t + δt to denote quantities at the beginning and the end of a time step δt. Based on the spring vector at time t, Qt1, we make a prediction for the new spring vector at time t + δt such that:

| (8) |

Next, we determine the correction to this prediction using a semi-implicit method:30

| (9) |

Using the appropriate spring force relation, Equation (9) can be recast as a cubic scalar equation that allows for the determination of .35 Based on Qt1 and the local fluid velocity, the incremental work δw done on a polymer by the fluid over a time δt is calculated through:

| (10) |

For a transition between any two states, the total work w done by the fluid on a polymer is computed by summing up δw through the course of a dynamic trajectory.

2.3 Free energy landscape and elasticity

The first experimental demonstration of the JE considered a system defined as an RNA molecule maintained at a defined extension by a conservative force field.21 In that study, the system was transitioned between states of varying molecular extension by “pulling” on the ends of the RNA using optical tweezers in the absence of flow. In our work, the system is defined as a single polymer molecule driven by flow, and the terminal states of the system are defined by the end-to-end molecular extension of the polymer, regardless of flow. In this way, the system is transitioned between initial and final states of predefined molecular extension by imposing a fluid flow that induces conformational changes in the polymer molecule. Once the molecule reaches a predefined final extension, the work calculation along the dynamic trajectory is halted. Conceptually, halting the work calculation can be envisioned as analogous to “switching off” the imposed flow and maintaining the molecule at the final extension by a conservative field. This step allows for the equilibration of the system to the new steady state. However, this step is not necessary for a dynamic trajectory, because equilibration at the final steady-state does not contribute to the work calculation and therefore does not affect the work relation.20

In order to calculate free energy landscapes, polymer molecules are transitioned though a series of states defined by molecular extension λi, where the subscript i = [1, 2] represents the initial and final states, respectively, by increasing the flow strength through a series of steps. Once a polymer reaches the desired final state (final molecular extension λ2), then the work calculation is terminated. Here, a dynamic trajectory is considered as the stretching trajectory up to the first time a molecule reaches a target final extension. For λ-DNA in tethered uniform flow, the flow strength is stepped through Pe = 20, whereas in planar extensional flow, the flow strength is stepped up to Pe = 16.2. Flow strengths were determined in order to ensure that polymer chains are stretched above 70% of the contour length. At each step, we determine the work distribution and the corresponding ΔF from the work relation. In this way, the free energy and therefore the stored elastic energy of a polymer can be determined over a range of energies up to 3 orders of magnitude. Chain elasticity is determined by differentiating the free energy with respect to chain extension.

2.4 Housekeeping power

In order to determine the scaling properties of the housekeeping power (see Results and Discussion), we performed BD simulations of polymers wherein the fluid flow rate is held constant after a polymer molecule has reached its final steady state molecular stretch. In these calculations, a dynamic trajectory is considered as the stretching trajectory beyond the first time a molecule reaches a target final extension. Housekeeping power is calculated as the slope of the transient average work done by the fluid after several Hencky strain units, where the average work is linear function of time.33 Using this approach, the housekeeping power was calculated for up to 5 orders of magnitude in flow strength.

2.5 Work analysis

In order to calculate the work done by the fluid on polymers from experimental single polymer stretching data, we consider two stretching regimes of a molecule: coiled conformations (where the molecule is modeled with a constant drag coefficient ζ)8,36 and stretched conformations (where slender body theory is applicable).37,38 The work rate is determined based on Equation (6), or more specifically Equation (10), but now with the spring force replaced by the hydrodynamic drag exerted on the molecule. We determined the work rate in the coiled regime by considering the drag force and velocity on a sphere of size Rg in extensional flow, given by , where λ is the polymer extension. Here, we also used the relationship for ideal linear chains such that the radius of gyration is related to the mean-squared end-to-end distance 〈λ2〉.5 In the coiled state, we calculated ζ using scaling arguments and center-of-mass diffusion coefficients from prior single molecule experiments on long DNA molecules.11 We determined ζ = 0.0031 pN·s/µm at a solution viscosity ηs = 8.4 cP, conditions under which the transient stretching data was obtained. In the strongly stretched regime, the work rate based on slender body theory is given by , where d = 2 nm is the molecular diameter of DNA (Supplementary Information†).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Jarzynski equality for polymeric systems

For a general microscopic system, external forces can be applied to perform work and transition the system between states. External forces can follow autonomous or non-autonomous dynamics. In autonomous dynamics, all of the external forces or agents are maintained at fixed values, and the system evolves accordingly. However, in non-autonomous dynamics, at least one of the forces varies systematically in time. Based on these distinctions, an equilibrium state is defined when the applied forces are conservative and autonomous.39 Therefore, the equilibrium statement of the JE (Equation (1)) can be applied to systems where the initial and final states are prescribed by autonomous and conservative forces. In this work, the terminal states of our system (defined by a polymer molecule at a fixed molecular extension) satisfy these conditions (see Methods).

Previous applications of the JE have focused on bead-tethered macromolecular systems. In this case, systems are driven from an initial equilibrium state (State a) to a final equilibrium state (State b) by applying forces that follow non-autonomous dynamics, and work is performed on the system. Upon reaching the final state (State b), no additional work is done on the system. A physical example is an RNA “pulling” experiment performed using optical tweezers, wherein the bead-tethered ends of an RNA hairpin are perturbed by optical forces.21 Here, the bead is maintained in a potential energy well given by the optical trap.

In this work, we show that the JE can be applied to polymeric systems driven by hydrodynamic flow, provided that the initial and final states of the polymer are defined by molecular extension (see Methods). We note that the initial state must be a well-defined equilibrium state. In particular, we show that transitions between states of defined molecular extension can be analyzed in the context of nonequilibrium work relations. Work is performed on a polymer chain by a hydrodynamic force (via fluid motion), which changes the molecular stretch of a polymer between an initial state (State a, initial molecular extension λ1) and a final state (State b, final molecular extension λ2). In one approach, transitions between states of defined molecular extension λi are made by increasing flow strength through a series of steps in fluid velocity. Upon reaching the final state, an external conservative field (in the absence of flow) could be used to allow for equilibration, though this approach is not easily available in experiments. In a second approach that is more amenable to experiments, a polymer can be transitioned from an equilibrated state at λ1 (zero flow) to a second nonequilibrated state of stretch λ2 by a large step in flow strength. We demonstrate the validity of both approaches in this article.

3.2 Work relations and system control parameters

Nonequilibrium work relations and fluctuation theorems have previously been considered in the context of dissipative forces.19,24,26 Furthermore, recent experiments have employed high-precision measurements involving optically trapped beads in the presence of flow to demonstrate the validity of these theorems.25,26,40 Here, we apply nonequilibrium work relations to dilute polymeric solutions driven by purely dissipative forces.

For dynamic processes driven by external fluid flows, the JE requires an accurate definition of work done on bodies suspended in a flowing fluid. A large body of previous work in this area has focused on force-extension measurements, where the work done on a molecule is simply defined by the force exerted to stretch the molecule over a well-defined distance.21–23 However, polymeric systems driven by hydrodynamic flow require a definition of the work performed on a polymer molecule by a flowing fluid.41 Recently, a work definition was used to show that a Hookean dumbbell model for polymers in extensional flow satisfies a fluctuation theorem,42 however, the Hookean model does not accurately capture dynamics in strong flows and it is unclear a priori that this work expression yields the equilibrium Jarzynski work. In this section, we show theoretically that this work definition is the valid expression for applying the equilibrium statement of the JE to polymer molecules driven by flow.

To obtain a work expression for a Langevin description of polymers in flow, we first consider a classical mechanical system consisting of N particles in contact with a heat bath at temperature β−1. The microscopic state of the system is specified by the 3N-dimensional position vector r and the 3N-dimensional momentum vector p of the particles through the Hamiltonian H (r, p). In order to move to a Langevin description of the system, it is essential to identify a reaction coordinate x (r) through which a potential of mean force Φ (x) can be expressed as:

| (11) |

where δ(x) is the Dirac-delta distribution. Consider the case where the system is now guided (or perturbed) by an external potential Vα, such as in steered molecular dynamics simulations.23 Here, α is the control parameter that defines the state of the system. In this case, the potential function of the new system U (x; α) is the sum of the potential of mean force and the external potential, such that U (x; α) = Φ (x) + Vα (x). When applying the JE to systems controlled by conservative forces, the work definition is given as , where τ is the time required to reach the new state.

Systems driven by nonconservative forces (e.g., as encountered in hydrodynamic flows) are typically multidimensional in the reaction coordinate. Therefore, we consider a Langevin description of polymer chain dynamics in flow such that:

| (12) |

where x is the multidimensional reaction coordinate and as such represents the position vector of beads, ζ is the scalar drag coefficient, ξ represents the Brownian force given by a Gaussian white noise with intensity 2ζkBT, U (x; α) is the sum of the potential of mean force (or connector potential of the springs, ϕ(c) (x)) and the external potential Vα(t) (x), f = ζu (x) is the hydrodynamic force due to fluid flow, and u is the unperturbed fluid velocity at x. We note that the external potential Vα(t) (x) is analogous to the potential exerted by an optically trapped bead that is tethered to a polymer terminus and may be used in equilibrating the system at a fixed extension.

In order to determine the state of the system, we consider a set of control parameters α that describe how a system can be transitioned between states. For polymeric systems driven by external flows, there are two distinct choices for the control parameters. In the first case, the control parameters are chosen as α = {λ, x}, while in the second case, the control parameter can be chosen as α = {ε̇}. In this work, we choose the set of control parameters α = {λ, x}, such that the instantaneous state of a polymer chain is defined by the molecular extension of a polymer in flow.

We now follow closely the work relation given by Hatano and Sasa,19 which was derived for equilibrium and nonequilibrium steady states governed by Langevin dynamics:

| (13) |

where ϕ = −logρss (x;α) and ρss is the probability distribution of the steady state corresponding to α. For equilibrium steady states, ρss follows the Gibbs-Boltzmann distribution, and therefore ϕ = −β (F − U). First, consider the case where the system is perturbed by the direct manipulation of only λ, such as the RNA pulling experiment with optical tweezers in the absence of flow. In this case, α = {λ}, and Equation (13) reduces to the equilibrium JE, as given in Equation (1), with .

Now, consider our choice for control parameters α = {λ, x} for polymer chains driven by flow. For this choice of α, the transient state of the system is defined by molecular extension and position in flow. Inserting α = {λ, x} into Equation (13) yields:

| (14) |

where the integrand in the exponential on the left hand side is the rate of work done by the fluid on the polymer, given by ẇ = ∂tU + u·∇U. Interestingly, this rate of work ẇ is equivalent to the rate of work defined for particles in flow by Speck et al.,33 which was derived in an entirely different context. The first term in the rate of work (∂tU) can be interpreted as the work done by an external conservative field in stretching the polymer chain. This term is exactly zero in our approach because the transition is driven by hydrodynamic flow. The second term in the rate of work (u·∇U) can be physically interpreted as the work done by a parcel of fluid on a polymer chain, which amounts to the convective derivative of the potential function.

We apply this general approach to single molecule experiments and simulations of polymers stretching in flow. First, we simulate the stretching of single polymer chains between states of defined extension by applying hydrodynamic forces. Initially, a polymer is held at an initial molecular extension (λ1). Next, a nonequilibrium process is initiated by an external flow, which stretches the polymer between states of molecular extension. Once the molecule reaches the new state defined by λ2, the work calculation is halted. For experimental data, polymer chains are transitioned between an equilibrium state at zero flow and a final state of constant extension by hydrodynamic flow in a microfluidic device.

It is worth mentioning that parameterizing states by molecular extension is akin to defining states by a fixed reaction coordinate, such that λ = |xNb − x1|. In this sense, the stiff-spring approximation is satisfied, and the free energy differences are equal to differences in potential of mean force, which is directly related to the free energy of the unperturbed molecule. For a polymer chain, the potential of mean force corresponds directly to the stored elastic energy in the chain.43 Furthermore, the elasticity is the corresponding force-extension behavior of a polymer chain and is defined as the derivative of the free energy with respect to molecular extension.31,44 Therefore, in this way, the determination of the equilibrium free energy landscape of the molecule allows for the determination of the stored elastic energy and corresponding chain elasticity.

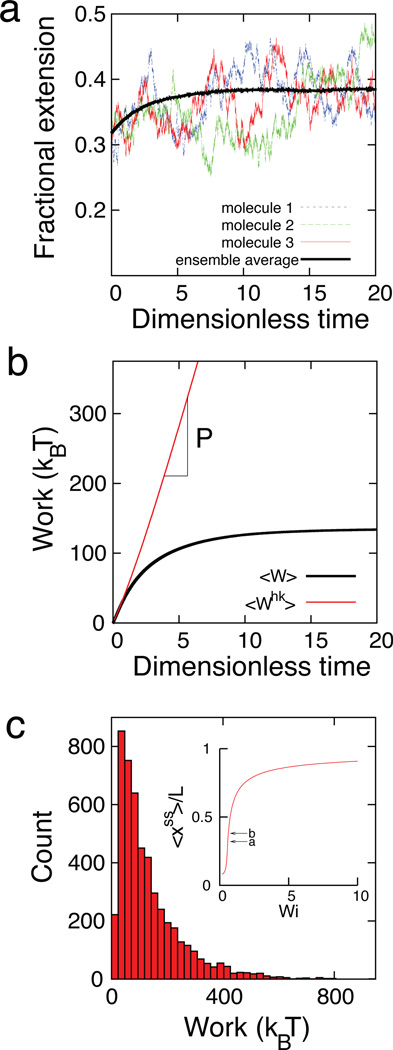

We first determined the work required to stretch polymers using Brownian dynamics simulations of coarse-grained polymer chains (see Methods). As a proof-of-principle demonstration, we analyzed flow induced conformational changes of polymer dumbbells modeled as double stranded DNA in a planar extensional flow (Fig. 1). In extensional flows, the dimensionless flow strength is given by the Weissenberg number (Wi = ε̇τR = Peτ̃R), where τR is the longest polymer relaxation time and τ̃R is the dimensionless form of τR. * Work is calculated for molecular stretching events, wherein a molecule is driven from an initial molecular extension (State a, λ1) to a second molecular extension (State b, λ2) by a step change in Wi, as shown in Fig. 1a. The average transient work for this process over an ensemble of polymers is given by the quantity 〈W〉, as shown in Fig. 1b. Work histograms are calculated by determining the work required to stretch an ensemble of individual molecules from State a to State b, as shown in Fig. 1c. After a polymer reaches State b, the average rate of work required to maintain the average molecular extension is zero for conservative forces or a non-zero constant at fixed Wi.33 For the case of a fixed flow rate, we define this constant as the housekeeping power P, which is the rate of work required to maintain an average polymer extension at a fixed flow rate. Housekeeping power is given by the slope of the transient housekeeping work P = d〈Whk〉/dt, as shown in Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1.

Nonequilibrium work calculations for λ-DNA (contour length L ≈ 21 µm) in extensional flow. (a) Trajectories of fractional polymer extension induced by Wi = 0.63, wherein molecules are stretched from a fractional extension λ1/L ≈ 0.32 (State a) to λ2/L ≈ 0.38 (State b). Single molecule trajectories and the ensemble average stretch are shown. (b) Transient average work trajectories, where 〈W〉 is the average work for a process wherein polymer molecules are stretched from State a to State b, and 〈Whk〉 is the housekeeping work required to maintain a polymer at an average steady state extension at State b. The slope of 〈Whk〉 gives the housekeeping power P. (c) Histogram of work required to stretch single polymers from State a to State b. (Inset) Steady state fractional extension 〈xss〉/L as a function of Wi in extensional flow.

3.3 Free energy landscapes and chain elasticity

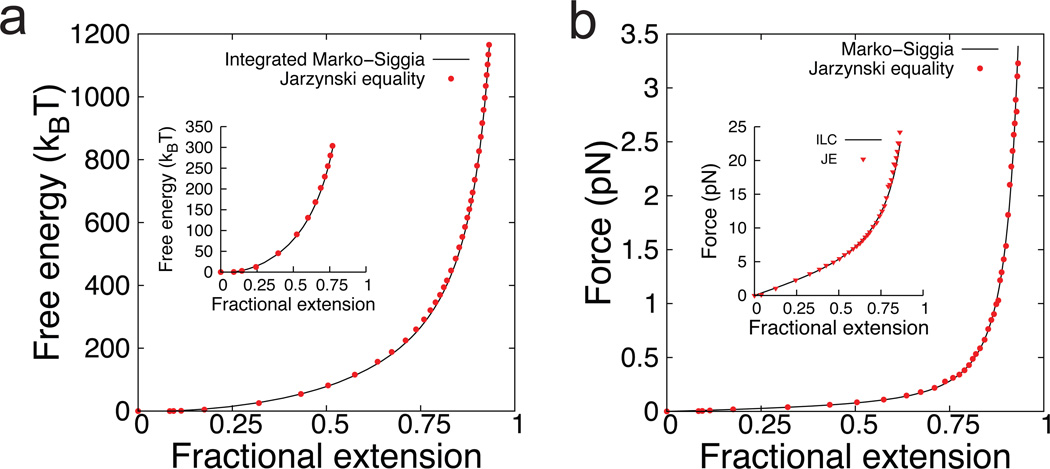

Using nonequilibrium work distributions, we applied the JE to calculate the stored elastic energy for polymer chains as a function of molecular extension, beginning with BD simulations (Fig. 2). We first determined the free energy landscape for single DNA molecules stretched in an extensional flow (Fig. 2a) and in tethered uniform flow (Fig. 2a, inset) using λ-DNA as a model system. In order to map the free energy landscape for λ-DNA from molecular stretching trajectories, we simulated the response of polymer chains to series of step increases in flow strength Wi. During transitions between successive steps of constant molecular extension, we determined the work done by the fluid to stretch a polymer from one extension to another. In this way, we used a method known as stratification,46 wherein the overall free energy change ΔFtot for a process is determined by summing the free energy changes for a series of sub-processes.

Fig. 2.

(a) Free energy landscape for λ-DNA (L ≈ 21 µm) determined from nonequilibrium dynamics in extensional flow using the JE. (Inset) Free energy landscape for λ-DNA determined in tethered uniform flow using the JE. The free energy at zero extension is defined as the reference state (Fo = 0). (b) Polymer elasticity for λ-DNA (L ≈ 21 µm) determined from dynamic data in extensional flow using the JE. (Inset) Polymer elasticity for a polystyrene molecule (L ≈ 1.2 µm) determined in extensional flow using the JE. ILC: inverse Langevin chain force-extension relation.

Stratification effectively divides (or stratifies) a process with a large free energy change into Nt sub-processes with small free energy changes (ΔFsub), which is relevant because the JE relies on an exponential Boltzmann weighted average of work values, as given by Equation (1). Therefore, the accuracy of free energy estimates given by the JE depends on adequate sampling of events associated with small work values, which typically comprise a small part of the work distribution. From this perspective, the application of JE to microscopic processes associated with large average dissipated work 〈wd〉 ≫ kBT generally requires larger ensembles, where the dissipated work wd = w − ΔF is the work lost during an arbitrary process. Work is a path function, such that the work obtained through a series of sub-processes is not directly additive in the context of work relations.46,47 However, free energy is a thermodynamic state variable, and the free energy changes for a series of sub-processes are additive. Therefore, the JE can be applied to each stratified sub-process, and the total free energy change can be computed by summing up the sub-process free energies ΔFtot =∑i ΔFsub,i. In using this stratification technique, we note that the initial states must be equilibrated. This condition is intrinsically satisfied for a dumbbell because it is a polymer model with a single mode. For the free energy calculation of polymer dumbbells shown in Fig. 2a, the overall molecular stretching process was stratified into Nt = 80 sub-processes. In this example, we determined the elastic properties of DNA, which is well described by the wormlike chain (WLC) or Marko-Siggia force-extension relation for semiflexible polymers.31 Overall, the JE performs very well in capturing the elastic chain energy over a wide range of molecular extensions, as determined from dynamic stretching trajectories in far-from-equilibrium hydrodynamic flow processes.

Nonequilibrium polymer dynamics in flow is governed by a balance between hydrodynamic forces that tend to stretch polymer chains, entropic restoring forces, and stochastic (Brownian) forces. Due to thermal motion, the work required to stretch a polymer in processes driven by hydrodynamic flow exhibits a distribution of values. Figure 1c shows the work distribution for one sub-process in extensional flow for a change in molecular stretch between λ1/L = 0.32 to λ2/L = 0.38, due to an imposed flow at Wi = 0.63. For this sub-process, the mean work 〈w〉 is 134.1 ± 2.7 kBT, the JE estimate of ΔF is 15.5 ± 0.7 kBT, and the actual ΔF given by the analytic WLC relation is 14.3 kBT. Remarkably, the JE is able to predict the free energy change for this process, despite the enormous amount of dissipated work 〈wd〉 ≈ 120 kBT associated with the stretching event. The convergence of the JE estimate as a function of ensemble size (for a single-mode elastic model for polymers) is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.†

The force-extension relation for a polymer can be calculated by differentiating the free energy with respect to molecular extension. We determined polymer elasticity from nonequilibrium dynamics for DNA, modeled as a semiflexible biopolymer (Fig. 2b), and polystyrene, modeled as a synthetic organic polymer (Fig. 2b, inset). The elasticity of DNA is well described by the WLC force relation, whereas the elasticity for flexible polymers such as polystyrene is typically modeled by the inverse Langevin (ILC) entropic force relation.35 In particular, we used Cohen’s Padé approximation for the ILC force, which provides an analytical expression for force as a function of molecular stretch.32 The stored elastic energy for ideal polymer chains48 scales as F ~ NK, where NK is the total number of Kuhn steps, which implies that a larger number of stratified sub-processes is required to map the free energy landscape of flexible polymers compared to semiflexible chains. Indeed, we found that a larger number of sub-processes Nt was required to determine the elasticity of polystyrene (Nt = 140) compared to DNA (Nt = 80), despite the fact that the contour length L for the polystyrene molecule was smaller than the contour length of stained λ-DNA (L ≈ 1.2 µm with NK ≈ 860 versus L ≈ 21 µm with NK ≈ 160, respectively)12. Polystyrene is a flexible polymer with a Kuhn step size bK=1.4 nm, two orders of magnitude smaller than the Kuhn length for intercalating dye-stained dsDNA (bK=132 nm).3†

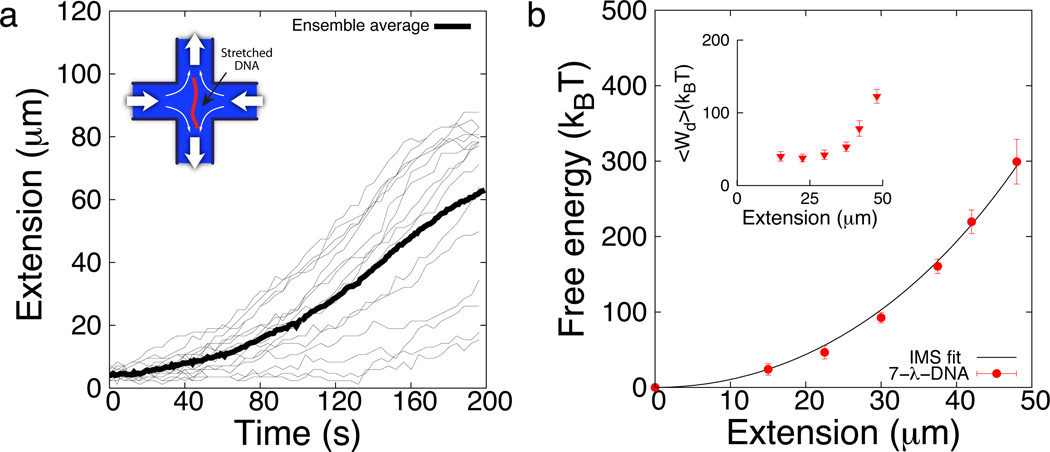

3.4 Analysis of single polymer experiments

We further applied this approach to single polymer dynamics experiments (Fig. 3). In particular, we analyzed data based on long concatemers of λ-phage DNA, in particular 7-λ-DNA, stretching in microfluidic devices obtained using single molecule fluorescence microscopy.8 We calculated the work done by the fluid on the polymer by considering the hydrodynamic drag forces using the Zimm model and slender body theory5,37 - with no adjustable parameters (see Methods). Using this approach, we calculated the work required to stretch a polymer from the coiled state to a predefined final extension based on single molecule stretching trajectories in planar extensional flow. We considered two different experimentally measured flow rates of Wi = 0.75 shown in Fig. 3a, and Wi = 0.98 shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.† In this way, we first determined a work distribution for given set of individual trajectories. Next, we applied the JE to determine the unperturbed free energy landscape of the molecule as shown in Fig. 3b. Despite the large values of dissipated work (Fig. 3b, inset), the elastic energy is in good agreement with that expected from the integrated Marko-Siggia force relation given bK = 132 nm and the contour length as a fitting parameter, L ≈ 112 µm (r2 = 0.998). The commonly accepted values for the Kuhn step size for natural dsDNA and dsDNA labeled with YOYO-1 are 106 nm and 132 nm, respectively.3,11 Given these values, the contour length of natural (unlabeled) and YOYO-1 labeled 7-λ-DNA are approximately 112 µm and 154 µm, respectively.8

Fig. 3.

Application of the nonequilibrium work relation to experimental data on polymer dynamics. (a) Individual (light) and ensemble average (dark) stretching trajectories of 7-λ-DNA molecules in extensional flow at Wi = 0.75 obtained from prior single molecule polymer dynamics experiments8. (Inset) Schematic of a stretched molecule in a planar extensional flow. (b) Free energy landscape determined from applying JE to experimental stretching trajectories. Solid line is the integrated Marko-Siggia (IMS) relation with contour length as fitting parameter. (Inset) Average dissipated work as a function of molecular extension. Data shown are mean values ± SD.

3.5 Relating housekeeping power to viscosity and stress

Dynamic processes driven by flow may result in nonequilibrium steady states of polymer extension,33 which are distinct from steady states at true thermodynamic equilibrium. For steady states at thermodynamic equilibrium, the applied power P (known as housekeeping power49) or rate of work 〈ẇ〉 required to maintain the state is zero. However, the house-keeping power is constant and positive (P > 0) in linear flows such as shear and extensional flow. For nonequilibrium steady states, the fluid performs work to maintain polymer extension at a constant (average) molecular stretch, which needs to be accounted for in constructing work distributions. Although previous work has studied housekeeping power in the context of shear flow,33,41,43 these studies have been limited to infinitely extensible Hookean chains. Here, we investigate the relationship between the housekeeping power and flow type for linear flows including shear and extensional flow, and we further explore the implications of applied power on the Jarzynski formalism.

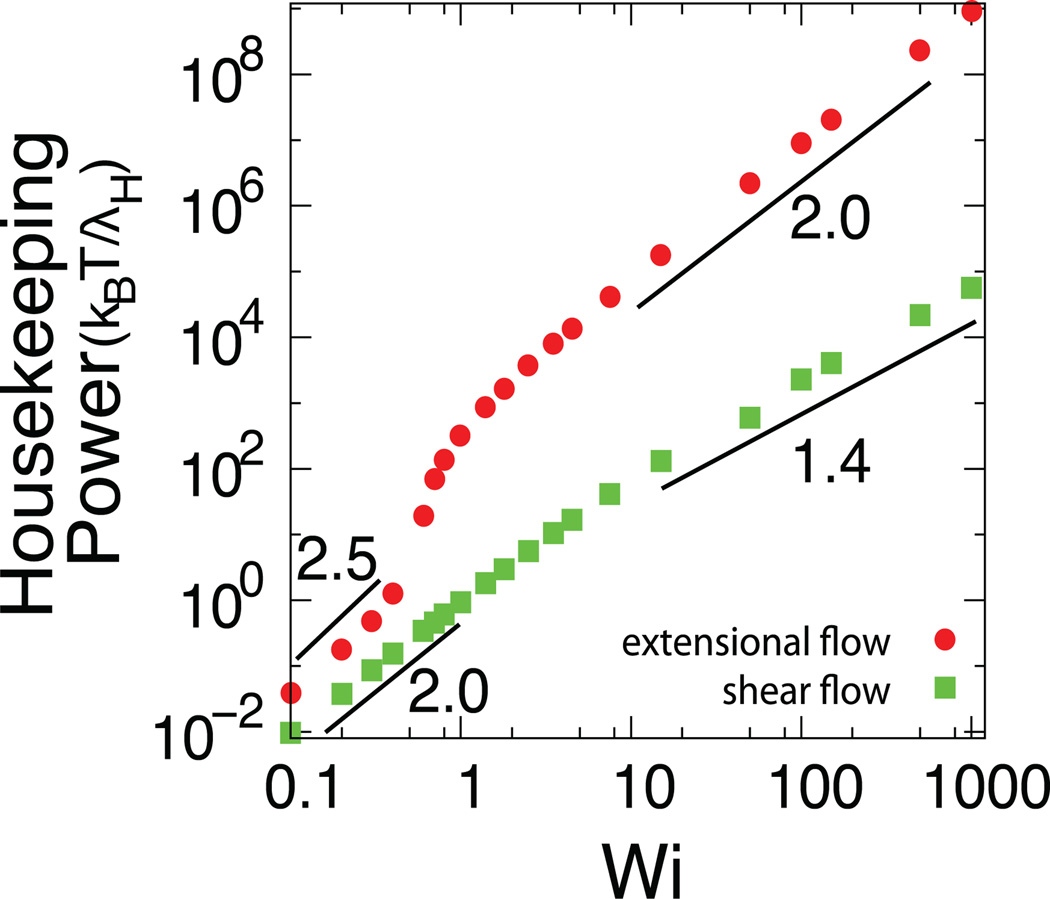

We determined the housekeeping power for DNA using BD simulations, which includes the effects of finite extensibility using the WLC model. The housekeeping power for DNA in shear and extensional flow appear to follow power law scalings as a function of Wi, as shown in Fig. 4. To understand the origin of the power law scalings in different flow regimes, we expressed the rate of work performed by the fluid on the polymer as:

| (15) |

where f (xk, Fspr) in the final expression is a general function. The form of f depends on flow type, the radius of gyration tensor Rij, Wi, and is related to well known viscometric functions. For Hookean springs with linear force-extension relations such that Fspr = HQ1, the functional form becomes f = H 〈Q1,1 Q1,2〉 in shear flow, whereas in planar extensional flow, where is the force constant, and the additional subscripts 1 and 2 are the flow and gradient directions in shear flow and extensional/compressional axes in extensional flow.

Fig. 4.

Housekeeping power as a function of dimensionless flow strength Weissenberg number Wi in shear and extensional flow for λ-DNA using a dumbbell model, where λH = ζ/4H is the relaxation time of the corresponding Hookean polymer chain.

We determined f as a power law function of Wi for DNA molecules (modeled by non-linear WLC elasticity) in flow by performing a series of BD simulations, such that f ~ Wiν and P ~ Wi1+ν, where ν is a scaling exponent. In shear flow, polymer chains behave as Hookean springs for Wi < 1, which yields f ~ H 〈Q1,1 Q1,2〉 ~ Wi1.0 and a power scaling P ~ Wi2.0. For higher Wi shear flows Wi > 1, nonlinear chain elasticity plays a role in the stretching process such that f ~ Wi0.45, thereby yielding a power scaling P ~ Wi1.45. In extensional flow, we find that f ~ Wi1.4 for Wi < 1, thereby yielding P ~ Wi2.4. This scaling exponent is slightly larger than the result expected for a Hookean chain in extensional flow because of the nonlinearity in the chain elasticity. In particular, this nonlinear force-extension regime is sampled significantly by the chain for Wi > 0.5. For stronger extensional flows Wi > 1, we determined f ~ Wi1.0 which yields a power scaling P ~ Wi2.0. All of these scaling arguments are in good agreement with the scalings obtained directly from the applied power given by equation (15), as shown in Fig. 4. In general, the applied power P for a given Wi is larger for extensional flows compared to shear flow, which is expected because extensional flow consists of purely extensional/compressional components, whereas shear flow has equal contributions of rotation and extension.34

Housekeeping power P from the Jarzynski formalism is related to bulk polymer viscometric functions. For linear flows such that u (xk) = κ · xk, the applied power given by equation (15) is related to the strain rate (ε̇ in extensional flow or γ̇ in shear flow) multiplied by elements of the polymer contribution to the stress tensor given by Kramers expression , where τp is the nonisotropic part of the polymer contribution to stress, and n is the number density of polymers.43 In this way, elements of κ connect applied power to viscometric functions. For example, in shear flow P = −γ̇τ12 = γ̇2η (γ̇) where η is the shear viscosity, and in extensional flow P = − ε̇ (τ11 − τ22) = ε̇2ηE (ε̇) where ηE is the extensional viscosity.43

4 Conclusions

In this work, we apply nonequilibrium work relations to polymer dynamics. We show that a nonequilibrium work expression based on the Jarzynski/Hatano/Sasa framework is valid for polymeric systems driven far from equilibrium by hydrodynamic forces. Using this approach, we show that it is possible to calculate materials properties such as polymer chain elasticity from molecular stretching trajectories of single polymers in external flows. We use a combination of simulations and analysis of experimental data to demonstrate that the JE successfully captures polymer chain elasticity regardless of flow type (extensional or uniform flow), model type or level of discretization (single mode or multi-bead-spring chains, see Supplementary Fig. S3 †), or polymer type (modeled as a semiflexible biopolymer or synthetic chain). Based on this work, nonequilibrium work relations appear to be well-suited to play a key role in determining properties of soft materials from dynamic processes in flow.

From a broader perspective, our work provides the necessary theoretical framework that allows for determination of fundamental properties such as stored elastic energy and elasticity from the motion of single polymers in flow. In this way, the equilibrium properties of soft condensed matter systems can be determined using dynamic information, which is a new approach in the field of complex fluids. We also show that important bulk rheological quantities such as viscosity are connected to work calculations. This connection provides a fundamental consideration for bulk dynamical quantities from an equilibrium perspective. Moving beyond polymeric systems, we anticipate that our framework can be extended to colloidal suspensions, for example, in the calculation of energy differences between colloidal states wherein interactions between colloidal particles are “tuned” in a defined way.

Beyond the application of JE to dynamic processes in flow, it is conceptually interesting to observe that fundamental equilibrium properties can be determined from forces that do not appear to traditionally define equilibrium states, for example, those encountered in the flow and deformation of matter. Strikingly, it appears that the nature of the force responsible for transitions between any two equilibrium states is insignificant in the determination of the energy difference between these states. Previous studies on determining free energy landscapes from nonequilibrium processes have focused on how far from equilibrium the process is, but little attention has been given to the fundamental nature of the process itself. However, this work implies that the equilibrium energy difference between two states can be determined regardless of the type of force that drives changes in state (e.g., conservative or nonconservative), which is a key concept in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher Jarzynski for useful discussions. This work was supported by a Packard Fellowship from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and an NIH Pathway to Independence Award (4R00HG004183-03) to C.M.S. and a Dow Chemical Company Fellowship in Chemical Engineering to F. L.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [Details of Brownian dynamics simulations and single molecule data analysis]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

The longest polymer relaxation time τR is determined by analyzing polymer relaxation trajectories following the cessation of flow. In particular, τR is the time constant obtained from fitting an exponential decay to the mean squared end-to-end distance of the polymer molecule in the regime of linear elasticity. For dsDNA, this regime is typically chosen as < 30% of the contour length of the polymer molecule.8,45

The Kuhn step size bK=132 nm applies to dsDNA stained with the intercalating dye YOYO-1 at a dye:bp ratio of ≈1:4,11 which is commonly used in single polymer experiments.

References

- 1.Neuman K, Lionnet T, Allemand J-F. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2007;37:33–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins T, Smith D, Larson R, Chu S. Science. 1995;268:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.7701345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reccius CH, Mannion JT, Cross JD, Craighead HG. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:268101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.268101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto O, Sturm S, Laohakunakorn N, Keyser U, Kroy K. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1780–1787. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson RG. The Dynamics of Complex Fluids. Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gennes P-G. J. Chem. Phys. 1974;60:5030–5042. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groisman A, Steinberg V. Nature. 2000;405:53–55. doi: 10.1038/35011019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder CM, Shaqfeh ESG, Chu S. Macromolecules. 2004;37:9242–9256. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mai DJ, Brockman C, Schroeder CM. Soft Matter. 2012;8:10560–10572. doi: 10.1039/C2SM26036K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerashchenko S, Chevallard C, Steinberg V. Europhys. Lett. 2005;71:221. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DE, Perkins TT, Chu S. Macromolecules. 1996;29:1372–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaqfeh E. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2005;130:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mavrantzas VG, Ö ttinger HC. Macromolecules. 2002;35:960–975. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavrantzas VG, Theodorou DN. Macromolecules. 1998;31:6310–6332. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarzynski C. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:2690–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarzynski C. Phys. Rev. E. 1997;56:5018–5035. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummer G, Szabo A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:3658–3661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071034098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatano T. Phys. Rev. E. 1999;60:R5017–R5020. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.r5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatano T, Sasa S-i. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:3463–3466. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarzynski C. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2011;2:329–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liphardt J, Dumont S, Smith SB, Tinoco I, Bustamante C. Science. 2002;296:1832–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.1071152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta AN, Vincent A, Neupane K, Yu H, Wang F, Woodside MT. Nat. Phys. 2011;7:631–634. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S, Khalili-Araghi F, Tajkhorshid E, Schulten K. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:3559–3566. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans DJ, Searles DJ. Phys. Rev. E. 1994;50:1645–1648. doi: 10.1103/physreve.50.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GM, Sevick EM, Mittag E, Searles DJ, Evans DJ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:050601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carberry DM, Williams SR, Wang GM, Sevick EM, Evans DJ. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:8179–8182. doi: 10.1063/1.1802211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latinwo F, Schroeder CM. Macromolecules. 2013;46:8345–8355. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jendrejack RM, de Pablo JJ, Graham MD. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:7752–7759. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somasi M, Khomami B, Woo NJ, Hur JS, Shaqfeh ESG. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2002;108:227–255. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Öttinger HC. Stochastic Processes in Polymeric Fluids: Tools and Examples for Developing Simulation Algorithms. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marko JF, Siggia ED. Macromolecules. 1995;28:8759–8770. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen A. Rheol. Acta. 1991;30:270–273. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speck T, Mehl J, Seifert U. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:178302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.178302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batchelor GK. An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh C-C, Li L, Larson RG. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2003;113:147–191. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radhakrishnan R, Underhill PT. Macromolecules. 2013;46:548–554. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batchelor GK. J. Fluid Mech. 1970;44:419–440. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson RG. Mol. Phys. 2004;102:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chernyak VY, Chertkov M, Jarzynski C. J. Stat. Mech.-Theory Exp. 2006:P08001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trepagnier EH, Jarzynski C, Ritort F, Crooks GE, Bustamante CJ, Liphardt J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:15038–15041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406405101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speck T. PhD Dissertation. University of Stuttgart; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma R, Cherayil BJ. Phys. Rev. E. 2011;83:041805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.041805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bird RB, Curtis CF, Armstrong RC, Hassager O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids. 2nd edn. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubinstein M, Colby RH. Polymer Physics. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins TT, Quake SR, Smith DE, Chu S. Science. 1994;264:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.8171336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pohorille A, Jarzynski C, Chipot C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:10235–10253. doi: 10.1021/jp102971x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McQuarrie DA. Statistical Mechanics. 2nd edn. University Science Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Gennes P-G. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oono Y, Paniconi M. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 1998;130:29–44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.