Abstract

The Cox maze procedure for the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation has been simplified from its original cut-and-sew technique. Various energy sources now exist which create linear lines of ablation that can be used to replace the original incisions, greatly facilitating the surgical approach. This review article describes the anatomy of the atria that must be considered in choosing a successful energy source. Furthermore the device characteristics, safety profile, mechanism of tissue injury, and ability to create transmural lesions of the various energy sources that have been used in the Cox maze procedure, along with the strengths and weaknesses of each device is discussed.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ablation, devices

The Cox maze procedure was introduced by Dr. James Cox at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis in 1987. The operation involved creating a number of incisions across both the right (RA) and the left atria (LA). These incisions form scar that block the propagation of electrical wave fronts. The surgical procedure was designed to block the multiple macroreentrant circuits that were believed at the time to be the mechanism responsible for atrial fibrillation (AF). Over the next decade, this operation became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF.1–4 The 10 year freedom from AF in our series has been 96%. These excellent results have been reproduced by other groups around the world.5–7 Despite its efficacy, this procedure was not widely performed because of its complexity and technical difficulty.

The introduction of ablation technology has significantly changed this attitude. To simplify the operation and make it easier to perform, the incisions of the traditional cut-and-sew Maze procedure were replaced with linear lines of ablation. Various energy sources have been used, including cryoablation, radiofrequency (RF) energy, microwave, laser, and high-frequency ultrasound. This article will review the present state of the art in surgical ablation therapy.

Requirements for Surgical Ablation

For ablation technology to reliably replace an incision in AF surgery, it must meet several important criteria. First, it must produce complete conduction block because this is the mechanism by which incisions prevent AF. Incisions either block activation wave fronts or isolate trigger foci. It has been demonstrated that nontransmural lesions, which leave only a thin rim of viable tissue, can cause conduction block during AF.8 However, our laboratory has shown that sinus rhythm and AF can conduct through even tiny gaps (≥1 mm) in ablation lines.9 The only guarantee of effectiveness of a procedure is the creation of a fully transmural lesion that always results in conduction block. Thus, a device must be able to make transmural lesions on the heart from either the epicardial or the endocardial surface for ablation performed during surgery. If an ablation is created on the epicardial surface of a beating heart, transmural lesions can be difficult because of the heat sink effect of the circulating intracavitary blood.10,11 This fact has hindered some technologies in replacing the surgical incision lines of the original Cox maze procedure.

The second important criterion for a technology to be useful for ablation is that it must be safe. Precise definition of dose–response curves to limit excessive or inadequate ablation must be developed. It is also necessary to know the effects of the specific ablation technology on surrounding vital structures, such as the coronary sinus, coronary arteries, heart valves, and esophagus. Third, a device should make AF surgery easier and quicker to perform. This requires features such as rapid lesion formation, ease of use, and adequate length and flexibility of the device.

Finally, to be optimal, the device should be adaptable for minimally invasive approaches. This would require the ability to insert the device through small thoracotomies or ports. It would also require the device to be capable of creating epicardial transmural lesions on the beating heart.

Anatomic Considerations

It is necessary to understand wide variation in human atrial wall thickness to define the performance of any epicardial ablation device. Several studies have determined that the regional wall thicknesses of the RA and LA are highly variable in humans. In normal individuals, the atrial thickness in the posterior LA between the pulmonary veins ranged from 2.3±1.0mm between the superior veins to 2.9±1.3mm between the inferior veins in one study.12 In patients with a history of AF, the tissue was thinner ranging from 2.1 ± 0.9 mm to 2.5 ± 1.3 mm. In both the groups, the thickness increased moving from the superior to the inferior veins. In normal individuals, the thickness in the LA just above the coronary sinus was 6.5 ± 2.5 mm. The thickness of Bachmann’s bundle, a preferential conduction pathway between RA and LA crossing across the roof of the atria in the transverse sinus, is 4.6 ± 1.1 mm (range: 1.7–9.3 mm) in normal individuals.13 In patients with any cardiac disease, the mean LA thickness is 5.2 ± 1.8 mm (range: 3–15 mm). The crista terminalis in the RA has an average thickness of 7.7 ± 2.4 mm (range: 4.2–12.6 mm). These values encompass muscle thickness only and did not include overlying fat or underlying free-running pectinate muscles, which exist in both the RA and the LA (which are not continuous with the epicardial surface). In normal individuals, the fat layer at the posterior mitral annulus can be 10 mm thick or more, which is important because epicardial fat can be an obstacle to achieve adequate depth of penetration for most ablation technologies.14 Finally, as patients grow older, their chamber size and wall thickness increase.15 These highly variable wall thickness and anatomy provide a challenge to any unidirectional device to achieve transmural lesions.

Cryoablation

Device Characteristics

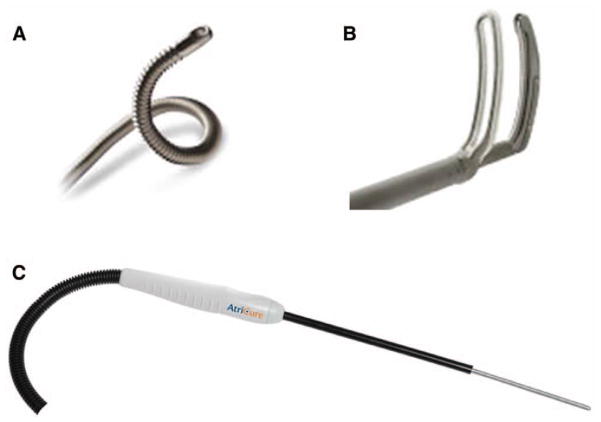

There are two commercially available sources of cryo-thermal energy that are being used in cardiac surgery. The older technology uses nitrous oxide and is manufactured by AtriCure, Inc. (Cincinnati, OH): the cryoICE, which uses a 10 cm malleable probe on a 20 cm shaft (Figure 1). Medtronic ATS (Minneapolis, MN) has developed a device using argon. The ATS Medtronic Cryo can be used in two ways, either as a malleable single-use cryosurgical probe with an adjustable insulation sleeve for varying ablation zone lengths or as a two-in-one convertible device that incorporates a clamp and surgical probe. At one atmosphere of pressure, nitrous oxide is capable of cooling tissue to −89.5°C, while the argon device has a minimum temperature of −185.7°C.

Figure 1.

Panel (A) shows the ATS Medtronic Cryo probe and panel (B) is the clamp that can be used with the probe. Panel (C) shows the AtriCure cryoICE probe. Both probes are malleable.

Cryothermal energy is delivered to myocardial tissue by using a cryoprobe. This probe consists of a hollow shaft, an electrode tip, and an integrated thermocouple for distal temperature recording. A console houses the tank containing the liquid refrigerant. This liquid is pumped under high pressure to the electrode through an inner lumen. Once the fluid reaches the electrode, it converts from a liquid to a gas phase, absorbing energy and resulting in rapid cooling of the tissue. The gas is then aspirated by vacuum through a separate return lumen to the console. At the tissue–electrode interface, there is a well-demarcated line of frozen tissue, sometimes termed an “ice ball.”

Mechanism and Histology of Tissue Injury

Cryothermal energy destroys tissue through the formation of intracellular and extracellular ice crystals. This disrupts the cell membrane and the cytoplasmic organelles. Following the cryoablation, there is development of hemorrhage, edema, and inflammation over the first 48 hours. Irreversible injury is usually evident within this early time period. There is also evidence of apoptosis, the induction of which may expand the area of initial cell death.16

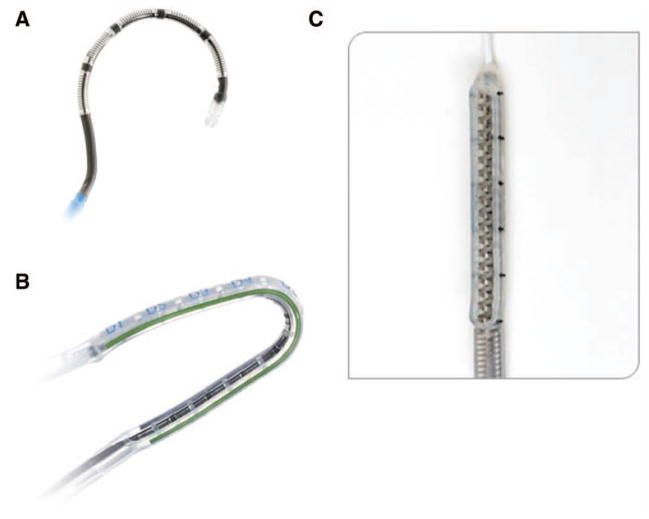

Healing is characterized by extensive fibrosis, which begins approximately 1 week after lesion formation. Cryoablation is the only currently available energy source that does not alter tissue collagen; it preserves normal tissue architecture. This makes it an excellent energy source for ablation close to valvular tissue or the fibrous skeleton of the heart. Histologically, lesions exhibit dense homogeneous scar formation without cicatrization and a lack of thrombus formation over the lesions (Figure 2). The homogeneous scar has been shown to have a low arrhythmogenic potential.17–19 In a human study, specimens that underwent endocardial cryoablation on the arrested heart were examined. Histology revealed extensive myocellular damage and transmural lesions. Morphologic features included sarcoplasmic vacuolization, increased cell roundness with indistinct membranes, and loss of contraction bands.20

Figure 2.

Histologic sections of canine (cryo) and porcine (bipolar radiofrequency [RF]) atrial tissue after ablation. Ablations were performed and then animals were survived out to 30 days; then sacrificed and tissue samples were taken. Transmural scar measured 3.5mm in width in tissue ablated with cryo (B), and 3.0 mm in width in that created with bipolar radiofrequency. A and C represent viable atrial tissue.

Ability to Create Transmural Lesions

The size and depth of cryolesions are determined by numerous factors, including probe temperature, tissue temperature, probe size, the duration and number of ablations, and the particular liquid used as the cooling agent.19 With conventional nitrous oxide, 2 to 3 minute ablations have been shown to reliably create transmural lesions on both RA and LA. Likely because of the heat sink generated by circulating endocardial blood, epicardial cryolesions on the beating heart with nitrous oxide have not been transmural.21

There are an increasing number of studies investigating the use of argon cryoablation. Of three published animal studies, only one reported all samples to be transmural.1,22,23 The remaining animal studies showed that 25–93% of lesions were transmural in beating heart models. Doll et al.1 examined epicardial cryoablation for 2 minutes at −160°C. They were able to produce transmural lesions 62% of the time around the pulmonary veins. Five of the six lesions on the RA appendage were transmural, but only two of the eight (25%) on the LA appendage were transmural. Using the cryoclamp device epicardially on a beating heart in the canine model, 93% of lesions were transmural.23 Thus, the clamp device appears to be capable of creating transmural epicardial lesions. However, there has been concern regarding the use of this device on the beating heart due to fear of freezing the intracavity blood with subsequent embolization. In our laboratory, five of the 10 pigs undergoing argon cryoablation on the beating heart showed severe signs of emboli, with necropsy-confirmed pulmonary embolism in three and a large ischemic brain infarct in one animal.

Safety Profile

Cryoablation has the benefit of preserving the fibrous skeleton of the heart and thus is one of the safest of the technologies available. Nitrous oxide cryoablation has extensive clinical use and has an excellent safety profile. While experience has shown that cryothermal energy appears to have no permanent effects on valvular tissue or the coronary sinus, experimental studies have shown late hyperplasia of coronary arteries, and thus, these structures should be avoided.20,24–26 Esophageal injury is of concern as well. With epicardial cryoablation in a sheep model, seven of eight cases produced a mild or moderate esophageal lesion.1 In addition, a study aimed at evaluating the histologic changes induced on the esophagus by surgical ablation therapy reported endocardial cryoablation for 60 seconds that resulted in intensive esophageal lesions in two of six sheep. Epicardial cryoablation for 120 seconds produced mainly mild alterations.27

There have been a number of clinical reports on argon cryo-ablation. The two largest studies, one with 28 patients and the other with 63 patients, reported no ablation-related complications or deaths.2,28–30

Cryoablation is unique among the presently available technologies, in that it destroys tissue by freezing instead of heating. The biggest advantage of this technology is its ability to preserve tissue architecture and the collagen structure. The nitrous oxide technology reliably creates transmural lesions and generally is safe except around coronary arteries. Argon-based technology has not been studied as extensively, but it appears to be able to reliably create endocardial transmural lesions on the arrested heart. The ability of cryothermy to create epicardial transmural lesions on the beating heart is unclear, but available evidence suggests that it is unreliable in this setting. Cryoablation has been shown to cause coronary injury and its use should also be avoided near the esophagus for the same reason. Early clinical results have shown a good safety profile.

The potential disadvantages of this technology include the relatively long time necessary to create an ablation (2–3 minutes; Table 1). There also is difficulty in creating lesions in the beating heart because of the heat sink of the circulating blood volume. The cryoclamp device may overcome this problem as early work showed 93% transmurality on the beating heart.23 However, if blood is frozen, it coagulates, and resultant thromboembolism may be a potential risk of epicardial cryo-ablation on the beating heart.

Table 1.

Comparison of Ablation Energy Sources

| Energy Source | Pros | Cons | Current Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo | Consistent transmural lesions with defined ablation times, long track record of use, tissue death without collagen matrix destruction | Requires several minutes for each ablation, potential collateral injury | Used in stand-alone Maze procedures and in lesion subsets; used as adjunct to radiofrequency; excellent for perivalvular tissue |

| Bipolar radiofrequency | Consistent transmural lesions, requires only seconds to complete lesions, real-time measurement of tissue conductance to ensure transmurality | May require multiple applications to achieve transmurality; typically requires access to endocardial surface | Used in stand-alone Maze procedures and lesion subsets |

| Unipolar radiofrequency | Can be applied to epicardial surface or endocardial surface | Epicardial application may not produce transmural lesions due to heat sink effect of blood; no real-time transmurality measurement; potential to create collateral damage | Used in stand-alone Maze procedure or as adjunct with other energy sources |

| Laser | Lesions require seconds to create, can be applied to epicardial surface or endocardial surface, good penetration of adipose tissue | No real-time transmurality measurement; potential to create collateral damage | No current clinical devices |

| Microwave | Can be applied to epicardial surface or endocardial surface | Requires several minutes for each ablation; epicardial application may not produce transmural lesions due to heat sink effect of blood; no real-time transmurality measurement; potential to create collateral damage | No current clinical devices |

| High-intensity focused ultrasound | Can be applied to epicardial surface or endocardial surface; defined depth of penetration may limit collateral damage | Requires several minutes for each ablation line; no real-time transmurality measurement | No current clinical devices |

Unipolar Radiofrequency Energy

Radiofrequency energy has been used for cardiac ablation for many years in the electrophysiology laboratory.31 It was one of the first energy sources to be used in the operating room for AF ablation. Radiofrequency energy can be delivered by either unipolar or bipolar electrodes.

Device Characteristics

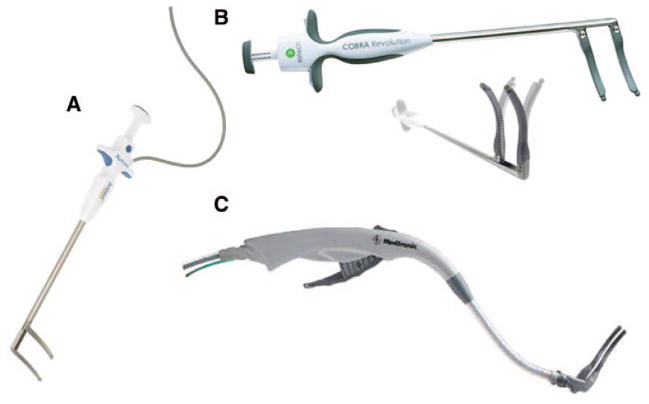

Estech (San Ramon, CA) has two unipolar surgical probes, the Cobra Adhere XL Probe and the Cobra Cooled Surgical Probe. Both are segmented flexible and malleable devices with multiple electrodes. The cooled device has internal saline cooling. To maintain probe position during beating heart applications, the Cobra Adhere XL (Figure 3) provides suction stabilization to the probe device, while the Cobra Cooled Surgical Probe does so for a minimally invasive approach.

Figure 3.

Panel (A) shows the Cobra Cooled Surgical radiofrequency (RF) Probe and panel (B) shows the Cobra Adhere XL RF Probe. Panel (C) shows the nContact RF VisiTrax. Both the Adhere and the VisiTrax use suction to maintain contact with the atrial surface.

The VisiTrax is available from nContact (Raleigh, NC) and is a coiled electrode that is held in place with suction and irrigated with saline for cooling. It comes in a 3 cm and 5 cm version. The device is designed to be used in open or closed chest procedures.

Medtronic has developed the Cardioblate Standard Ablation Pen and the Cardioblate XL Surgical Ablation Pen. These are pen-like, irrigated unipolar RF devices used to make point-by-point ablations by dragging them across tissue to make a linear lesion. The Cardioblate XL has a 20 cm shaft and is designed to be used through a port or small thoracotomy.

Mechanism and Histology of Tissue Injury

Radiofrequency energy uses an alternating current in the range of 100–1,000 kHz. This frequency is high enough to prevent rapid myocardial depolarization and the induction of ventricular fibrillation, yet low enough to prevent tissue vaporization and perforation. Resistive heating occurs only within a narrow rim of tissue in direct contact with the electrode, usually <1 mm. The deeper tissue heating occurs via passive conduction. With unipolar catheters, the energy is dispersed between the electrode tip and a passive electrode, usually the grounding pad applied to the patient.

The lesion size depends on electrode-tissue contact area, the interface temperature, the current and voltage (power), and the duration of delivery. The depth of the lesion can be limited by char formation at the tissue–electrode interface. To resolve this problem, irrigated catheters were developed, which reduces char formation by keeping temperatures cooler at the tissue interface. These irrigated catheters have been shown to create larger volume lesions than dry RF devices.32,33 On histologic evaluation of RF lesions, a focal coagulation necrosis predominates acutely. This correlates with the irreversible nature of the injury that occurs at high temperatures. There is destruction of myocardial/collagen matrix and replacement with fibrin and collagen in chronic studies. In chronic models, contraction and scarring occurs with large lesions. At very high temperatures (>100°C), char formation predominates. Char presents as an impediment to heat transduction and has been associated with asymmetrical ablations.

Ability to Create Transmural Lesions

The dose–response curves for unipolar RF have been described.34–36 While unipolar RF has been shown to create trans-mural lesions on the arrested heart with sufficiently long ablation times (60–120 seconds) in animals, there have been problems in humans. After 2 minute endocardial ablations during mitral valve surgery, only 20% of the in vivo lesions were transmural.35 Epicardial ablation has been even more difficult. Animal studies have consistently shown that unipolar RF is incapable of creating epicardial transmural lesions on the beating heart.36,37 A recent clinical study confirmed this problem. Epicardial RF ablation in humans resulted in only 7% of lesions being transmural, despite electrode temperatures of up to 90°C.38

Safety Profile

Because RF ablation is a well-developed technology, much is known about its safety profile. The complications of unipolar RF devices have been described after extensive clinical use and include coronary artery injuries, cerebrovascular accidents, and the devastating creation of esophageal perforation, leading to atrioesophageal fistula.27,39–42

Bipolar Radiofrequency Energy

Device Characteristics

Bipolar technology is incorporated into devices in two ways. One is in a clamp that applies energy between electrodes in the jaws of the clamp, which ablates the tissue between the two jaws of the device. The second way is a device in which the two electrodes are side by side, and the device is applied to either the epicardial or the endocardial surface.

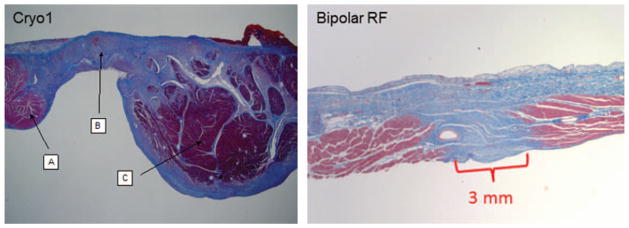

The Isolator Synergy clamp (AtriCure, Inc.) has two electrodes embedded in each 7 cm long jaw in configurations of various curvatures and are designed to clamp over the target atrial tissue (Figure 4). The device uses a continuous measurement of tissue impedance as a marker for the assessment of lesion transmurality. The conductance between the electrodes is measured during the ablation at 50 times per second. When the conductance drops to a stable minimum level (high impedance), this correlates well with both experimental and clinical histology assessment of transmurality. The algorithm allows for total energy delivery to be customized to the individual tissue characteristics.

Figure 4.

Panel (A) shows the AtriCure Isolator Multifunctional radiofrequency (RF) pen. The Coolrail Linear RF Pen is shown in panel (B). Panel (C) shows the Medtronic Cardioblate BP2 clamp.

AtriCure has also developed the Isolator Multifunctional Pen that uses bipolar energy through two side-by-side electrodes at the end of the handheld probe. The device can be used to record electrograms or pace in addition to using it to ablate. They also have developed the Coolrail Linear Pen that is a 30 mm side-by-side electrode that has a 7.5 cm shaft. The active electrode region is internally cooled with circulating saline. Both these devices are applied for a fixed period of time on the atrium because the algorithms that assess transmurality by measuring conductance between the two electrodes do not work when the electrodes are side by side (as they are on these devices) and not between the epicardial and the endocardial surface.

Medtronic markets two bipolar clamp devices, both with irrigated flexible jaws and an articulating head. The Cardioblate BP2 has a flexible neck and a 7 cm electrode, and a similar low-profile device, the Cardioblate LP, is for use through a small thoracotomy. Medtronic also offers a longer malleable clamp, the Cardioablate Gemini, which also can be used through a small lateral thoracotomy. All the Medtronic clamps are irrigated with saline to help increase the depth of penetration.

Estech (San Ramon, CA) offers two bipolar clamps, both called the Cobra Bipolar Clamp. One uses disposable electrode elements with a reusable clamp. The other is a single-use system.

Mechanism and Histology of Tissue Injury

In bipolar devices, alternating current is generated between two closely approximated electrodes. This results in a more focused ablation than with unipolar technology. Ablation occurs by resistive heating. As the energy passes between the two electrodes, temperatures reach 60–70°C between the electrodes but drops off quickly in neighboring tissue. There is minimal effect of convective cooling (Figure 5). Bipolar RF ablation results in discrete, transmural lesions, with no evidence of contraction or scarring. Multiple chronic animal studies have revealed no evidence of thrombus or stricture formation 30 days following ablation when examining the atria, vena cava, and pulmonary veins.43–46 In an animal model using the AtriCure and Medtronic clamps, microscopic examination showed that 99–100% of all lesions were transmural, continuous, and discrete with a single ablation using the conductance algorithm (Figure 2). Lesion width varied depending on tissue depth and the duration of ablation; the measured lesions were typically 2–3 mm but up to 5 mm in width on the thickest parts of the atrium. These studies and others have suggested that the bipolar technology produces consistent transmural lesions.

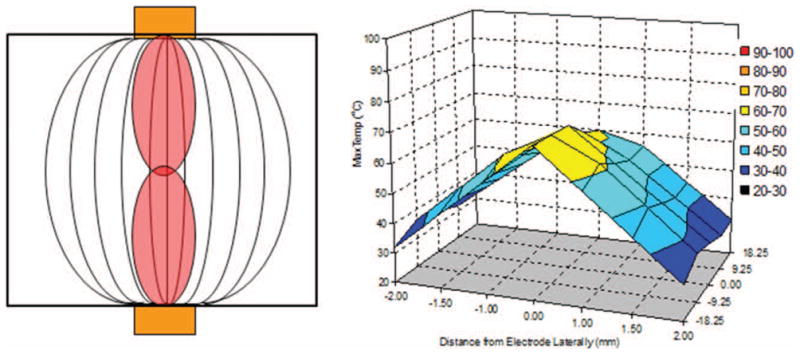

Figure 5.

Representation of cross section of bipolar radiofrequency ablation. The orange boxes represent the electrodes, the curved lines depict energy transduction between the electrodes. The curved lines correlate to temperature readings in ablated and nearby tissue which is depicted on the right.

Ability to Create Transmural Lesions

Bipolar clamps are the fastest and are reliable devices for creating transmural lesions in open procedures. Bipolar RF clamp devices are capable of creating transmural lesions without difficulty on the beating heart.46–48 This has been shown both in animals and in humans, with average ablation times between 5 and 10 seconds.3,43–45 However, one jaw must be introduced into the atrium. Application in humans without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass has to be done while balancing the risk of introducing air into the left atrium. Cryoablation can also effectively create transmural lesions when used for adequate time. Cryoablation requires much longer (2.5–3 minutes) ablations and is not as fast as bipolar RF ablations with a clamp.

Pen devices can be effective but must be used with caution. The Isolator pen has been shown to be reliable in creating transmural lesions in tissue up to 8 mm in thickness. However, atrial thickness varies greatly between patients and within atria. In studies in our laboratory, the Coolrail linear pen created transmural lesions only 80% of the time with a single application of the devices. Multiple applications may improve performance. However, no animal studies have been done to determine the effects of multiple ablations at a single site. With these devices, most nontransmural lesions occur at the ends of the line of ablation created by the device. Therefore, it is important to overlap the lesions when making an extended linear lesion to insure transmurality.

Safety Profile

Use of the bipolar RF clamp devices has eliminated most of the collateral damage that is created with the unipolar devices. The energy is focused between the two electrodes of the device, eliminating the diffuse radiation of heat. However, the devices with side-by-side bipolar electrodes have not been evaluated for safety and would potentially have the same problems as unipolar devices. Application of unipolar devices near the atrioventricular junction, including cryoablation, increases the risk of damaging coronary arteries.

Other Energy Sources

In the past, there have been other devices on the market based on different energy sources. These include microwave devices, lasers, and high-frequency ultrasound. None of these devices are presently available. Most of these devices failed to produce reliable transmural lesions.10 Clinical application resulted in high recurrence rates of AF.49–51

Summary

The development of ablation technology revolutionized the surgical treatment of AF. These ablation devices have made a rarely performed operation accessible to all cardiac surgeons. So at the present time, significantly more patients are undergoing AF surgery. However, a review of the STS database has shown that only one third of patients who could potentially benefit are receiving surgical treatment of their AF. These ablation technologies made possible the development of less-invasive procedures, possibly leading to a highly efficacious port access, beating heart procedure in the future.

Each ablation technology has its own shortcomings and complications (Table 1). In the future, it will be imperative to develop a more complete understanding of the effects of surgical ablation technology on atrial hemodynamics, function, and electrophysiology. The safety of ablation is dependent on an intimate knowledge of the technology being used. Thus, surgeons must develop accurate dose–response curves for all new devices in clinically relevant models on both the arrested and the beating heart. While most of the devices have been shown to be reliable in the arrested heart, few have shown the capability of creating reliable transmural lesions on the beating heart. The effect of any technology on vital structures and on atrial function also needs to be better delineated. Finally, it is essential that these devices be used according to manufacturers’ recommendations. For example, the active electrode surfaces on dry bipolar RF clamps need to be cleaned between ablation to remove excess blood. Desiccated blood on the active electrode surface can cause high resistance that can alter the energy delivery.

While new technology has led to progress, the field is still impaired by an inadequate understanding of the mechanisms of AF. With increased information, surgeons will be able to design an operation based on the mechanism or substrate responsible for the arrhythmia in each patient and tailor that operation to the specific atrial geometry. To develop a truly minimally invasive operation, electrophysiologic mapping may be necessary to confirm and guide therapy to allow for more precise isolation or ablation of specific anatomic or electrophysiologic substrates. Finally, clinical and experimental research on the various lesion sets that are being tried in the operating room will be essential for continuing progress.

The future presents AF surgeons with many opportunities and challenges. It is certain that the surgical treatment of AF will continue to undergo rapid evolution in the next decade, and much of this progress will be spurred by the use of new ablation technology.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 HL032257 and R01 HL 085113.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Damiano and Dr. Schuessler have received devices and/or research grants from Atricure, Boston Scientific (Guidant, AFx), Cryocath (ATS, Medtronic, Edwards, Estech, Medical CV, Medtronic, nContact. Dr. Damiano is a consultant to Atricure, Medtronic, and Edwards. Dr. Schuessler has received payment for services from Atricure. Dr. Melby has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Doll N, Kornherr P, Aupperle H, et al. Epicardial treatment of atrial fibrillation using cryoablation in an acute off-pump sheep model. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51:267–273. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JB, Cho WC, Jung SH, Chung CH, Choo SJ, Lee JW. Alternative energy sources for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery: Microwave ablation vs cryoablation. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1467–1472. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, et al. A prospective, single-center clinical trial of a modified Cox maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, et al. The Cox maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: Long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1822–1828. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)01287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raanani E, Albage A, David TE, Yau TM, Armstrong S. The efficacy of the Cox/maze procedure combined with mitral valve surgery: A matched control study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:438–442. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doty DB, Dilip KA, Millar RC. Mitral valve replacement with homograft and Maze III procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:739–742. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orszulak TA, Danielson GK. Cox-Maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: Mayo Clinic experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:30–37. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell MA, McRury ID, Everett TH, Li H, Mangrum JM, Haines DE. Morphological and physiological characteristics of discontinuous linear atrial ablations during atrial pacing and atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melby SJ, Lee AM, Zierer A, et al. Atrial fibrillation propagates through gaps in ablation lines: Implications for ablative treatment of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Epicardial microwave ablation on the beating heart for atrial fibrillation: The dependency of lesion depth on cardiac output. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuessler RB, Lee AM, Melby SJ, et al. Animal studies of epicardial atrial ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6 (12 suppl):S41–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platonov PG, Ivanov V, Ho SY, Mitrofanova L. Left atrial posterior wall thickness in patients with and without atrial fibrillation: Data from 298 consecutive autopsies. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:689–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saremi F, Channual S, Krishnan S, Gurudevan SV, Narula J, Abolhoda A. Bachmann Bundle and its arterial supply: Imaging with multidetector CT—Implications for interatrial conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias. Radiology. 2008;248:447–457. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482071908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong KN, Russo MJ, Liberman EA, et al. Effect of epicardial fat on ablation performance: A three-energy source comparison. J Card Surg. 2007;22:521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan NH, Tsao HM, Chang NC, Chen YJ, Chen SA. Aging dilates atrium and pulmonary veins: Implications for the genesis of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2008;133:190–196. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinbach JP, Weissenberger J, Aguzzi A. Distinct phases of cryogenic tissue damage in the cerebral cortex of wild-type and c-fos deficient mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1999;25:468–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holman WL, Ikeshita M, Douglas JM, Jr, Smith PK, Lofland GK, Cox JL. Ventricular cryosurgery: Short-term effects on intramural electrophysiology. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983;35:386–393. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetstein L, Mark R, Kaplan A, Mitamura H, Sauermelch C, Michelson EL. Nonarrhythmogenicity of therapeutic cryothermic lesions of the myocardium. J Surg Res. 1985;39:543–554. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(85)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lustgarten DL, Keane D, Ruskin J. Cryothermal ablation: Mechanism of tissue injury and current experience in the treatment of tachyarrhythmias. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1999;41:481–498. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(99)70024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manasse E, Colombo P, Roncalli M, Gallotti R. Myocardial acute and chronic histological modifications induced by cryoablation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:339–340. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt GB, Chard RB, Johnson DC, Ross DL. Comparison of early and late dimensions and arrhythmogenicity of cryolesions in the normothermic canine heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Skanes AC, et al. En bloc exclusion of the pulmonary vein region in the pig using off pump, beating, intra-cardiac surgery: A pilot study of minimally invasive surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1417–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milla F, Skubas N, Briggs WM, et al. Epicardial beating heart cryoablation using a novel argon-based cryoclamp and linear probe. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikat EM, Hackel DB, Harrison L, Gallagher JJ, Wallace AG. Reaction of the myocardium and coronary arteries to cryosurgery. Lab Invest. 1977;37:632–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holman WL, Ikeshita M, Ungerleider RM, Smith PK, Ideker RE, Cox JL. Cryosurgery for cardiac arrhythmias: Acute and chronic effects on coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe H, Hayashi J, Aizawa Y. Myocardial infarction after cryoablation surgery for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50:210–212. doi: 10.1007/BF03032288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aupperle H, Doll N, Walther T, et al. Ablation of atrial fibrillation and esophageal injury: Effects of energy source and ablation technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1549–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack CA, Milla F, Ko W, et al. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation using argon-based cryoablation during concomitant cardiac procedures. Circulation. 2005;112 (9 suppl):I1–I6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doll N, Kiaii BB, Fabricius AM, et al. Intraoperative left atrial ablation (for atrial fibrillation) using a new argon cryocatheter: Early clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1711–1715. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00869-5. discussion 1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S. The concomitant cryosurgical Cox-Maze procedure using Argon based cryoprobes: 12 month results. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2011;52:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viola N, Williams MR, Oz MC, Ad N. The technology in use for the surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:198–205. doi: 10.1053/stcs.2002.35292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khargi K, Deneke T, Haardt H, et al. Saline-irrigated, cooled-tip radiofrequency ablation is an effective technique to perform the maze procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:S1090–S1095. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa H, Wittkampf FH, Yamanashi WS, et al. Inverse relationship between electrode size and lesion size during radiofrequency ablation with active electrode cooling. Circulation. 1998;98:458–465. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kress DC, Krum D, Chekanov V, et al. Validation of a left atrial lesion pattern for intraoperative ablation of atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santiago T, Melo JQ, Gouveia RH, Martins AP. Intra-atrial temperatures in radiofrequency endocardial ablation: Histologic evaluation of lesions. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04990-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas SP, Guy DJ, Boyd AC, Eipper VE, Ross DL, Chard RB. Comparison of epicardial and endocardial linear ablation using handheld probes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:543–548. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bugge E, Nicholson IA, Thomas SP. Comparison of bipolar and unipolar radiofrequency ablation in an in vivo experimental model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.02.028. discussion 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santiago T, Melo J, Gouveia RH, et al. Epicardial radiofrequency applications: In vitro and in vivo studies on human atrial myocardium. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:481–486. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00344-0. discussion 486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kottkamp H, Hindricks G, Autschbach R, et al. Specific linear left atrial lesions in atrial fibrillation: Intraoperative radiofrequency ablation using minimally invasive surgical techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:475–480. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillinov AM, Pettersson G, Rice TW. Esophageal injury during radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:1239–1240. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.118041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laczkovics A, Khargi K, Deneke T. Esophageal perforation during left atrial radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:2119–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.08.007. author reply 2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demaria RG, Pagé P, Leung TK, et al. Surgical radiofrequency ablation induces coronary endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:277–282. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Chronic transmural atrial ablation by using bipolar radiofrequency energy on the beating heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:708–713. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.125057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Diodato MD, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Physiological consequences of bipolar radiofrequency energy on the atria and pulmonary veins: A chronic animal study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:836–841. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00716-1. discussion 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaynor SL, Ishii Y, Diodato MD, et al. Successful performance of Cox-Maze procedure on beating heart using bipolar radio-frequency ablation: A feasibility study in animals. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melby SJ, Gaynor SL, Lubahn JG, et al. Efficacy and safety of right and left atrial ablations on the beating heart with irrigated bipolar radiofrequency energy: A long-term animal study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vigilance DW, Garrido M, Williams M, et al. Off-pump epicardial atrial fibrillation surgery utilizing a novel bipolar radiofrequency system. Heart Surg Forum. 2006;9:E803–E806. doi: 10.1532/hsf98.20061019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voeller RK, Zierer A, Lall SC, Sakamoto S, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Efficacy of a novel bipolar radiofrequency ablation device on the beating heart for atrial fibrillation ablation: A long-term porcine study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinkenberg TJ, Ahmed S, Ten Hagen A, et al. Feasibility and outcome of epicardial pulmonary vein isolation for lone atrial fibrillation using minimal invasive surgery and high intensity focused ultrasound. Europace. 2009;11:1624–1631. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitnovetski S, Almeida AA, Goldstein J, Pick AW, Smith JA. Epicardial high-intensity focused ultrasound cardiac ablation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicol C, Kellerer D, Petrakopoulou P, Kaczmarek I, Lamm P, Reichart B. Long-term results after ablation for long-standing atrial fibrillation concomitant to surgery for organic heart disease: Is microwave energy reliable? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1156–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]