In the last decade the proportion of hemodialysis patients dialyzing with an arteriovenous fistula (prevalent fistula rate) in Canada, Europe, and Australia/New Zealand have been relatively high (50-90%) 1. In the United States, the prevalent fistula rate has improved dramatically and is now 57% 2. Achievement of these high rates has been due in part to national nephrology society guidelines and vascular access initiatives, such as the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) 3, Fistula First Initiative 2, European Best Practice Guidelines 4, and Canadian Society of Nephrology Clinical Practice Guidelines 5 which have focused on improving vascular access care. These guidelines and initiatives have targeted the following processes: (1) patient preparation for permanent access placement, (2) selection of type of permanent access with an emphasis on fistula evaluation and placement, and (3) cannulation. The guidelines and initiatives recognize that a multidisciplinary team comprised of nephrologists, vascular access surgeons, nephrology nurses, and vascular access coordinators are essential to accomplishing these goals 2, 3, 6. However, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, and several European countries with traditionally high prevalent fistula rates have recently reported proportions of incident hemodialysis patients with a fistula (incident fistula rates) below 50% 1. Furthermore, while the U.S. has seen rapid improvements in fistula rates in the prevalent population, this has not been accompanied by improvements in fistula rates among the incident population which have remained remarkably low at 18% 7.

In this issue of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Lopez-Vargas et al. report the results from a prospective multicenter cohort study within an Australian/New Zealand population which evaluated the implementation of national guidelines on timing of vascular access placement and type of vascular access placed in patients who initiated hemodialysis. The main outcome of this study was the proportion of patients with a functional fistula at dialysis initiation. Secondary outcomes included physician, patient, and organizational-barriers responsible for delays in achieving a functional fistula at dialysis initiation 8. Among the 319 patients who initiated hemodialysis during the six month study period, 39% of patients initiated hemodialysis with a fistula and 57% initiated hemodialysis with a catheter. Other important findings included (1) 66% and 79% of patients were under the care of a nephrologist by ≥12 and ≥3 months prior to initiating dialysis, respectively, (2) the median time from surgical referral to surgical evaluation and surgical evaluation to access surgery in this study were approximately 14 and 28 days, respectively, and (3) median eGFR at the time of surgical referral, access creation, and dialysis initiation were 7, 7, and 6 ml/min/1.73 m2, respectively.

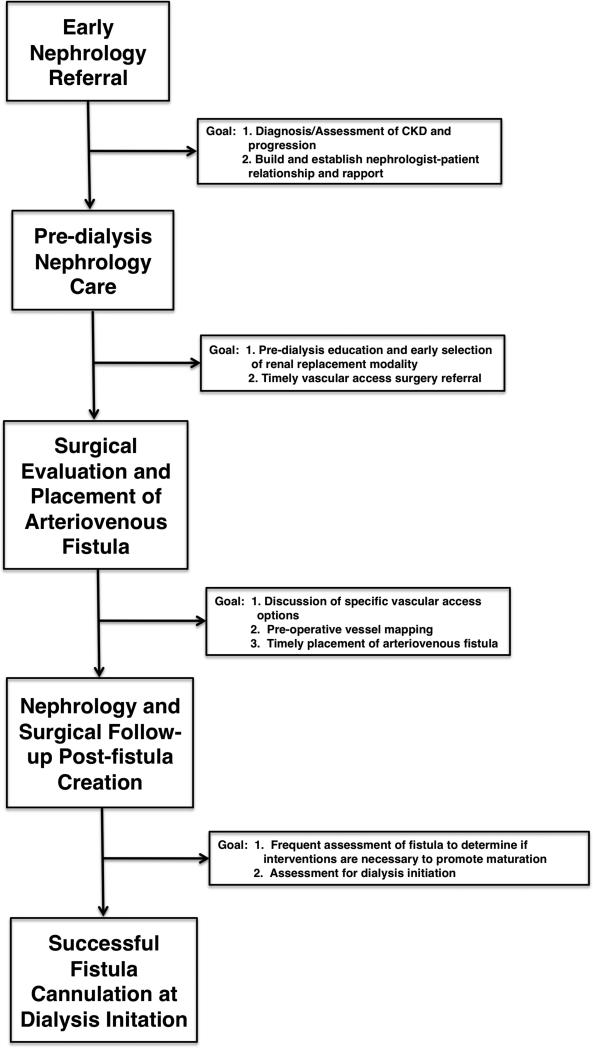

Previous studies 6, 9-11 have suggested that (1) early referral to a nephrologist from a primary care provider for chronic kidney disease (CKD) management, (2) timely discussion with the patient of future renal replacement modality and pre-dialysis education by the nephrologist, (3) referral to vascular access surgeon for evaluation and permanent access placement prior to dialysis initiation, and (4) close follow-up of the maturing fistula (outside of the dialysis unit) with an aggressive intervention policy (endovascular or surgical) for fistulae that fail to mature are important processes required to increase incident fistula rates (Figure 1). Close attention to all of these processes is essential in order to achieve the “holy grail” of pre-emptive fistula placement and successful cannulation with two needles by the dialysis staff at the first dialysis session. While many of the same processes are required to achieve a functional fistula in the prevalent population, the incident population, unlike prevalent dialysis patients, is not a “captive audience” which is seen thrice weekly by a healthcare provider. Thus, early and frequent pre-dialysis education and effective patient-physician interaction, while challenging, is crucial for improving fistula rates in the incident dialysis population.

Figure 1.

Model for Archieving Incident Arteriovenous Fistulae for Dialysis

There are several important observations from this study by Lopez-Vargez et. al that shed light on the processes need for improving incident fistula rates. First, late referral to nephrologists was actually low in their study population. The results from this study are similar to Europe and Canada where 62% and 63% of patients, respectively, were under the care of a nephrologist >12 months before initiating dialysis 12. In marked contrast, in the United States only 24% and 33% of patients had their initial nephrology evaluation >12 months and 0 to 12 months, respectively, prior to initiating dialysis, and 43% had no nephrology care prior to dialysis initiation 7. Thus, it does not appear that late nephrology referral is the major reason for low incident fistula rates in the Australia/New Zealand population in this study. Second, median time from surgical referral to evaluation and evaluation to surgical placement of permanent access was also relatively short. Interestingly, in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS), the United States had one of the lowest median times from surgical referral to evaluation and surgical evaluation to permanent access times at 7 and 7 days, respectively, but the worst incident fistula rate among surveyed countries 1. Thus, short times to surgical evaluation and placement of permanent access may not be relevant, if early referral to a nephrologist and timely referral to a surgeon does not also occur. Finally, the most striking observation from this study was low median eGFR at the time of surgical referral and access creation8. Even with early referral to a nephrologist and relatively short wait times for surgical evaluation and vascular access placement, the eGFRs suggest that the timing of surgical referral and vascular access placement occurred in the very late stages of the CKD and very close to the time of dialysis initiation. Therefore, what are the specific barriers that lead to delayed referral for surgical access evaluation and access placement?

Table 2 in the manuscript by Lopez-Vargas et al. outlines a model of perceived barriers to initiation of hemodialysis with a permanent access based on patient, physician, and organizational-levels 8. An important component of the vascular access process among those patients who have pre-dialysis nephrology care is interaction between the nephrologist and patient. It is challenging for nephrologists to accurately predict the rate of kidney disease progression and whether the patient will survive until kidney failure13, 14. Very frequently, dialysis initiation occurs in conjunction with a concurrent illness or hospitalization 15, 16. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the appropriate time to initiate pre-dialysis education for patients, discuss selection of renal replacement modalities, and subsequently when to refer patients for vascular access evaluation and surgery. The authors in this study reported that the majority of patients, 65%, attended pre-dialysis education sessions, and very few patients referred for surgical access evaluation and access placement refused or did not attend 8. What is unclear from this data is the level of eGFR at the time of initial pre-dialysis education and the interval from initial pre-dialysis education to surgical evaluation and access placement. This information may provide some further insight into whether the barriers are at the level of the physician (uncertainty by the nephrologist whether the patient's CKD will progress or patient will survive to dialysis initiation) or patient (denial of CKD and need for dialysis). Furthermore, it is quite evident from this study that early placement of permanent access enhances the likelihood that a patient initiates dialysis with a fistula or graft, and not a catheter (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.10-0.50; per 5 ml/min/1.73 m2 higher in eGFR).

From an organizational-level, there are currently no specific guidelines from nephrology societies in the United States or other countries that address implementing a specific plan or benchmarks for vascular access milestones to be achieved as GFR declines. The availability and widespread use of such benchmarks would likely address both patient-based and physician-based barriers and improve incident fistula rates. In an attempt to provide such benchmarks, Hakim et al. have proposed an algorithm for the planning and placement of permanent access based on eGFR in pre-dialysis patients 17 which includes: (1) initiation of pre-dialysis education at an eGFR≤ 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 , (2) surgical evaluation and permanent access placement at an eGFR≤ 20ml/min/1.73 m2, and (3) a mature fistula in place and ready to be used for dialysis at an eGFR≤ 10 ml/min/1.732 . Using eGFR-based guidelines would provide objective criteria for patient education and nephrologist decision-making in regards to referral for surgical evaluation and placement of permanent access, with a specific emphasis on fistulae. To support this point, in the study by Lopez-Vargas et. al., among patients who initiated dialysis with a catheter, 44% never received pre-dialysis education and 48% were never referred for surgical evaluation. Furthermore, among all centers in this study, the median time from first nephrology evaluation to dialysis initiation was rather long, ranging from 1.1 to 3.4 years 8. Moreover, eGFR-based guidelines would ultimately ensure timely placement of permanent access in all advanced CKD patients and allow for ample time for interventions to promote maturation, if necessary, as fistulae require several months for maturation 11, 18-20. In this study, among patients with permanent access placement, the median time from permanent access placement to initiation of dialysis was significantly longer in patients who initiated dialysis with a fistula or graft vs catheter (28 vs 8 weeks; p=0.001). However, some may argue that this approach may lead to unnecessary placements of fistulae in patients with slowly progressive kidney disease, particularly in the elderly population who may die before ever requiring dialysis 21.

What new information can be taken from this study? First, a major barrier influencing incident fistula rates is the delayed referral for surgical evaluation and fistula placement which occurred at an eGFR of 7 ml/min/1.732 for both events in this study 8. Second, among patients who initiated dialysis with a catheter a large percentage of these patients never received predialysis education and were not referred for surgical evaluation 8. The majority of countries participating in the DOPPS study have a high proportion of patients who have been under the care of a nephrologist for > 1 year prior to dialysis initiation 12. Thus, the primary focus now should be on the failures in the processes of care that occur after the patient has been under the care of a nephrologist. It appears that the most beneficial intervention towards improving incident fistula rates would be targeting earlier referral for surgical evaluation and permanent access placement. Future research studies need to directly evaluate in more detail the patient and nephrologist perspectives about pre-dialysis education and permanent vascular access placement prior to initiation of dialysis to determine the primary barriers leading to delayed referral for surgical evaluation and permanent access placement 25.

Acknowledgements

Research funding:Dr Lee is supported by NIH 5K23DK083528-02 and National Kidney Foundation Franklin McDonald/Fresenius Medical Care Young Investigator Award. Dr. Roy-Chaudhury is supported by NIH 5U01-DK82218, NIH 5U01-DK82218S (ARRA), NIH 5R01-EB004527, NIH 1R21-DK089280-01, a Clinical Translational Science Award from the University of Cincinnati, a VA Merit Review, and industry grants.

Financial Disclosure:Dr. Lee is a consultant for Proteon Therapeutics. Dr. Roy-Chaudhury is on the advisory board/consultant for Pervasis Therapeutics, Inc., Proteon Therapeutics, WL Gore, Bioconnect Systems, Philometron and NanoVasc and receives research support from Genzyme, BioConnect Systems, WL Gore and Shire.

This is a commentary on article Lopez-Vargas PA, Craig JC, Gallagher MP, Walker RG, Snelling PL, Pedagogos E, Gray NA, Divi MD, Gillies AH, Suranyi MG, Thein H, McDonald SP, Russell C, Polkinghorne KR.Barriers to timely arteriovenous fistula creation: a study of providers and patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):873-82.

References

- 1.Ethier J, Mendelssohn DC, Elder SJ, et al. Vascular access use and outcomes: an international perspective from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3219–26. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [January 23, 2011];Fistula First National Access Improvements Initiative. Available at: http://www.fistulafirst.org/.

- 3.Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:S176–S273. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tordoir J, Canaud B, Haage P, et al. EBPG on Vascular Access. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 2):ii88–117. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchill DN, Blake PG, Jindal KK, Toffelmire EB, Goldstein MB. Clinical practice guidelines for initiation of dialysis. Canadian Society of Nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl 13):S289–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allon M, Bailey R, Ballard R, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to hemodialysis access: prospective evaluation. Kidney Int. 1998;53:473–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Renal Data System . USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of CKD and ESRD in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Vargas PA, Craig JC, Gallagher MP, et al. Barriers to Timely Arteriovenous Fistula Creation: A Study of Providers and Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allon M. Fistula first: recent progress and ongoing challenges. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:3–6. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allon M. Current management of vascular access. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:786–800. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00860207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allon M, Robbin ML. Increasing arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients: problems and solutions. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1109–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendelssohn DC, Ethier J, Elder SJ, Saran R, Port FK, Pisoni RL. Haemodialysis vascular access problems in Canada: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS II). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:721–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eriksen BO, Ingebretsen OC. The progression of chronic kidney disease: a 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int. 2006;69:375–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drey N, Roderick P, Mullee M, Rogerson M. A population-based study of the incidence and outcomes of diagnosed chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:677–84. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00916-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishani A, Xue JL, Himmelfarb J, et al. Acute kidney injury increases risk of ESRD among elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:223–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu CY, Ordonez JD, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Go AS. The risk of acute renal failure in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74:101–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakim RM, Himmelfarb J. Hemodialysis access failure: a call to action-revisited. Kidney Int. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lok CE, Allon M, Moist L, Oliver MJ, Shah H, Zimmerman D. Risk equation determining unsuccessful cannulation events and failure to maturation in arteriovenous fistulas (REDUCE FTM I). J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3204–12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dember LM, Beck GJ, Allon M, et al. Effect of Clopidogrel on Early Failure of Arteriovenous Fistulas for Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2164–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy-Chaudhury P, Sukhatme VP, Cheung AK. Hemodialysis vascular access dysfunction: a cellular and molecular viewpoint. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1112–27. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Walter LC, et al. When to refer patients with chronic kidney disease for vascular access surgery: should age be a consideration? Kidney Int. 2007;71:555–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slinin Y, Guo H, Gilbertson DT, et al. Meeting KDOQI guideline goals at hemodialysis initiation and survival during the first year. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1574–81. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01320210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moist LM, Trpeski L, Na Y, Lok CE. Increased hemodialysis catheter use in Canada and associated mortality risk: data from the Canadian Organ Replacement Registry 2001-2004. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1726–32. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01240308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Chen SC. The state of chronic kidney disease, ESRD, and morbidity and mortality in the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S5–11. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05980809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi W, Macnab J, Lok CE, et al. Who should be referred for a fistula? A survey of nephrologists. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2644–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]