Abstract

Many older adults do not meet physical activity recommendations and suffer from health-related complications. Reinforcement interventions can have pronounced effects on promoting behavior change; this study evaluated the efficacy of a reinforcement intervention to enhance walking in older adults. Forty-five sedentary adults with mild to moderate hypertension were randomized to 12-week interventions consisting of pedometers and guidelines to walk 10,000 steps/day or that same intervention with chances to win $1-$100 prizes for meeting recommendations. Patients walked an average of about 4,000 steps/day at baseline. Throughout the intervention, participants in the reinforcement intervention met walking goals on 82.5% ± 25.8% of days versus 55.3% ± 37.1% of days in the control condition, p < .01. Even though steps walked increased significantly in both groups relative to baseline, participants in the reinforcement condition walked an average of about 2,000 more steps/day than participants in the control condition, p < .02. Beneficial effects of the reinforcement condition relative to the control condition persisted at a 24-week follow-up evaluation, p < .02, although steps/day were lower than during the intervention period in both groups. Participants in the reinforcement intervention also evidenced greater reductions in blood pressure and weight over time and improvements in fitness indices, ps < .05. This reinforcement-based intervention substantially increased walking and improved clinical parameters, suggesting that larger-scale evaluations of reinforcement-based interventions for enhancing active lifestyles in older adults are warranted. Ultimately, economic analyses may reveal reinforcement interventions to be cost-effective, especially in high-risk populations of older adults.

Keywords: older adults, reinforcement, pedometers, walking

Fewer than 5% of adults exercise at recommended levels, and activity levels decrease markedly with age (Hagstromer, Oja, & Sjostrom, 2007; Troiano, Berrigan, Dodd, Mâsse, Tilert, & McDowell, 2008). Particularly in older adults, low physical activity is related to medical problems, such as hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, reduced bone density, and greater risk of falls (Vogel, Brechat, Leprêtre, Kaltenbach, Berthel, & Lonsdorfer, 2009). Methods to increase activity levels may lead to readily discernable physical improvements in older adults.

Walking is the preferred form of physical activity, especially among older adults (Crespo, Keteyian, Heath, & Sempos, 1996; Prohaska et al., 2006). Low to moderate intensity physical activity such as walking can enhance lean body mass, increase strength, and improve cardiac function (Thompson, Gordon, Pescatello, & American College of Sports Medicine, 2010; United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2008). Walking 10,000 or more steps per day (nearly 5 miles) is recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine (Thompson et al., 2010), and this level of ambulatory activity has substantial benefits on fitness levels and cardiometabolic health (Anderson, Wadden, Bartlett, Zemel, Verde, & Franckowiak, 1999; Hakim et al., 1999; USDHHS, 2008).

Pedometers are a non-invasive and inexpensive method to monitor ambulatory activity, and they provide an objective indicator to assist individuals in moving toward greater activity levels (Bravata et al., 2007). Providing pedometers and daily step recommendations has some effects on improving activity levels and associated health outcomes (e.g., Richardson, Newton, Abraham, Sen, Jimbo, & Swartz, 2008). However, adherence to exercise regimens is poor (Burke, Dunbar-Jacob, & Hill, 1997; Day, Fildes, Gordon, Fitzharris, Flamer, & Lord, 2002; Dishman, Sallis, & Orenstein, 1985; Linke, Gallo, & Norman, 2011), and walking generally increases by only about 2,000 steps per day when pedometers and walking recommendations are given (Bravata et al., 2007; Richardson et al., 2008).

Reinforcement interventions are gaining increasing popularity in the medical field (Sindelar, 2008) and can be applied to impact lifestyle changes on a number of dimensions. They are efficacious for reducing substance use (Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006), enhancing weight loss (Petry, Barry, Pescatello, & White, 2011; Volpp, Troxel, Norton, Fassbender, & Loewenstein, 2008), and improving medication adherence (Petry, Rash, Byrne, Ashraf, & White, 2012). Thus, reinforcement interventions have potential to improve outcomes in many domains.

Some have argued that providing tangible reinforcers may reduce internal motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999), but this concern may apply primarily to reinforcing monotonous or non-personally meaningful tasks (Cameron, Banko, & Pierce, 2001). In the treatment of substance use disorders in which reinforcement interventions have been most extensively studied (Lussier et al., 2006), reinforcing abstinence leads to no change in internal motivation to reduce drug use relative to non-reinforcement interventions (Budney, Higgins, Radonovich, & Novy, 2000; Ledgerwood & Petry, 2006), and reinforcement procedures yield consistently improved substance abuse outcomes (Lussier et al., 2006).

Reinforcement interventions are based on principles of operant behavior and behavioral economics. A behavior that is positively reinforced is likely to increase in frequency (Ferster & Skinner, 1957), and therefore reinforcing objective indices of exercising should increase the probability of an individual exercising again in the future. People overvalue proximal events and subjectively devalue events that are delayed in time (Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999). Thus, reinforcement interventions that provide reinforcers frequently, and as immediately as possible upon demonstration of the behavior targeted for change, are more efficacious than those that infrequently reinforce behavior change (Lussier et al., 2006). Because magnitude of reinforcers clearly impacts efficacy, interventions that provide larger reinforcers are more effective than those that arrange smaller reinforcers (Dallery, Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2001; Lussier et al., 2006). However, people tend to overvalue low probability high magnitude events (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001), and therefore reinforcement interventions that provide occasional large value reinforcers can change behaviors at relatively low overall costs (Petry, Alessi, Hanson, & Sierra, 2007). Moreover, intermittent reinforcement is associated with behaviors that are more resistant to extinction (Ferster & Skinner, 1957; Nevin & Grace, 2000).

These behavioral principles may help explain why many individuals fail to meet healthy activity guidelines. The benefits of exercising are delayed in time (improved fitness and weight loss take weeks or months to achieve), and they are somewhat abstract in nature (i.e., feeling “better”). On the other hand, the negative consequences of a sedentary lifestyle can be delayed and uncertain; not everyone who is inactive develops diabetes or has a heart attack. The long-term consequences of an inactive lifestyle, therefore, may be heavily discounted in the moment-by-moment decision making process about whether to exercise or not.

Reinforcement interventions re-arrange the environment so that the benefits of healthy behavioral choices have more proximal and concrete positive consequences (Petry, 2012). They have been extensively researched and are highly effective in encouraging abstinence from substances (Lussier et al., 2006), which in essence reinforce the absence of a behavior. Reinforcing specific behaviors such as exercising is more straightforward.

Initial studies of reinforcement interventions for increasing activity levels yielded potential benefits on increasing running and bicycle pedaling but were limited to very small samples of youth or young adults (DeLuca & Holbern, 1992; Epstein, Thompson, Wing, & Griffin, 1980; Kau & Fisher, 1974; Keefe & Blumentahl, 1980; Wysocki, Hall, Iwata, & Riordan, 1979). In these studies, participants received self-selected reinforcers (i.e., toys, social activities, or returns of deposited items) for participating in exercise classes, pedaling bicycles or running, while being observed by others. All but one study (Epstein et al., 1980) utilized non-randomized designs, in which each participant served as his or her own control before and/or after the reinforcers were introduced.

More recently, Finkelstein, Brown, Brown, and Buchner (2008) randomized 51 older adults to a control condition in which they wore a pedometer and were encouraged to increase aerobic activities (defined as 10 minutes or more of pedometer-registered continuous walking, jogging or running) or that same intervention plus cash, ranging from $10 to $25 per week depending on the average daily duration of aerobic activity (i.e., $10 per week for averaging 15 minutes per day, and up to $25 per week for averaging 40 minutes per day of aerobic activities). Participants in the reinforcement condition registered a mean of 35.0 ± 0.9 minutes of aerobic activity per day versus 19.5 ± 0.8 minutes per day for those in the control condition. Only 7% of control participants met the public health recommendations of moderate physical activity (at least 5 days per week of 30 minutes per day) versus 38% of participants who received reinforcement. This study demonstrated strong beneficial effects of reinforcement for improving aerobic ambulatory activities, but fewer than half of the patients who received reinforcers achieved the recommended goals, perhaps in part because no reinforcement was awarded until the end of the 4-week intervention period. Providing reinforcers in greater temporal proximity to walking may encourage a greater proportion of older adults to walk at high levels. Further, arranging reinforcement for longer durations than 4 weeks may sustain high levels of ambulatory activities, and longer-term high frequency activity levels are needed to realize health benefits.

Other applications of reinforcement interventions to promote greater physical activity involve large scale employee health models (e.g., Butsch et al., 2007; Morgan et al., 2011; Neville, Merrill, & Kumpfer, 2011). These efforts have resulted in mixed effects, perhaps in part because behavioral economic and behavioral analytical principles were not fully considered in the intervention design. Many such programs, for example, offer only a single chance at earning reinforcers and do not reinforce behavior change in close temporal proximity to when physical activity levels increase. Further, most only provide modest levels of reinforcement.

The present study evaluated the efficacy of a reinforcement intervention for increasing ambulatory activities in sedentary older adults, and it instituted reinforcement procedures consistent with behavioral economic and behavior analytic principles. Specifically, participants were reinforced for each day they met ambulatory activity guidelines (i.e., walked >10,000 steps per day), and reinforcement, in the form of increasing chances to win $1 to $100 prizes, was provided weekly for 12 weeks. This reinforcement system was selected based on its efficacy in altering other behaviors (Petry et al., 2007, 2011; Rosen et al., 2007) and consistency with behavioral principles (Petry, 2012). Older sedentary adults randomized to receive this reinforcement intervention were hypothesized to increase the proportion of days on which they walked 10,000 or more steps compared to those randomized to an attention control condition.

Increasing walking by about 4,000 steps per day can results in reductions in blood pressure in those with mild to moderate hypertension (Moreau et al., 2001). This study, therefore, enrolled sedentary older adults with elevated blood pressures to ascertain whether the reinforcement intervention would decrease blood pressure. The reinforcement intervention was also hypothesized to improve other health (e.g., weight and waist circumference) and fitness indices both during the period reinforcement was in effect and following its cessation.

Methods

Participants

Forty-five older adults were recruited through advertisements placed throughout the University Health Center and in newspaper advertisements in the surrounding area towns stating that sedentary adults age 55 and older were needed for a study of methods to promote walking. Inclusion criteria were: age 55 – 75 years; walking >1,000 but <6,000 steps per day on average as assessed by 7-day pedometer readings (this criterion was not disclosed to potential participants; it was chosen because these ranges fall within the average daily steps of sedentary older adults (Basset, Wyatt, Thompson, Peters, & Hill, 2010), and extremely sedentary individuals may be unable to increase levels to those recommended in this study); willing to meet weekly for 12 weeks; physically able to walk 10,000 steps per day per physician permission (i.e., absence of substantial joint, hip or back problems that could interfere with walking, or heart attacks in past year); and blood pressure 120–160 mmHg systolic or 80–100 mmHg diastolic. Individuals with lower blood pressures were not included because they would be unlikely to realize blood pressure reductions, and patients with blood pressures above these ranges may require immediate medical intervention. Patients were asked about blood pressure medications they were taking at time of study entry and throughout participation, but no attempt was made to prevent physician-initiated changes in medications during study participation.

Exclusion criteria were: body mass index greater than 40 because this level of obesity may impact walking ability; major uncontrolled psychiatric illness (actively suicidal, psychotic, etc.); or, in recovery from pathological gambling due to potential similarity of the reinforcement intervention with gambling (but see Petry et al., 2006).

Procedures

Individuals who called in response to the ads were screened over the phone. Those who appeared to meet criteria (n = 88) were invited to attend two in-person assessments, scheduled one week apart, at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine. They were told they needed written physician permission to participate in a study in which they would be asked to walk 10,000 steps per day.

Written informed consent, as approved by the University of Connecticut School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board, was obtained at the first assessment. Participants received an Omron HJ-112 pedometer (Kyoto, Japan) that stores seven days of steps in memory. They were asked to engage in usual activities for the next seven days while wearing the pedometer at all times, except when bathing or sleeping.

At the second assessment, the numbers of daily steps were obtained from the pedometers. Participants who walked between 1,000 and 6,000 steps per day on average were invited to continue in the study. Those exceeding the walking criteria (n = 16), were given information about methods to enhance walking but did not continue in the study. One consented patient failed to obtain physician permission for study participation (n = 1), and another declined participation before attending the second assessment (n = 1). These patients likewise were not continued in the study and were given educational materials related to walking.

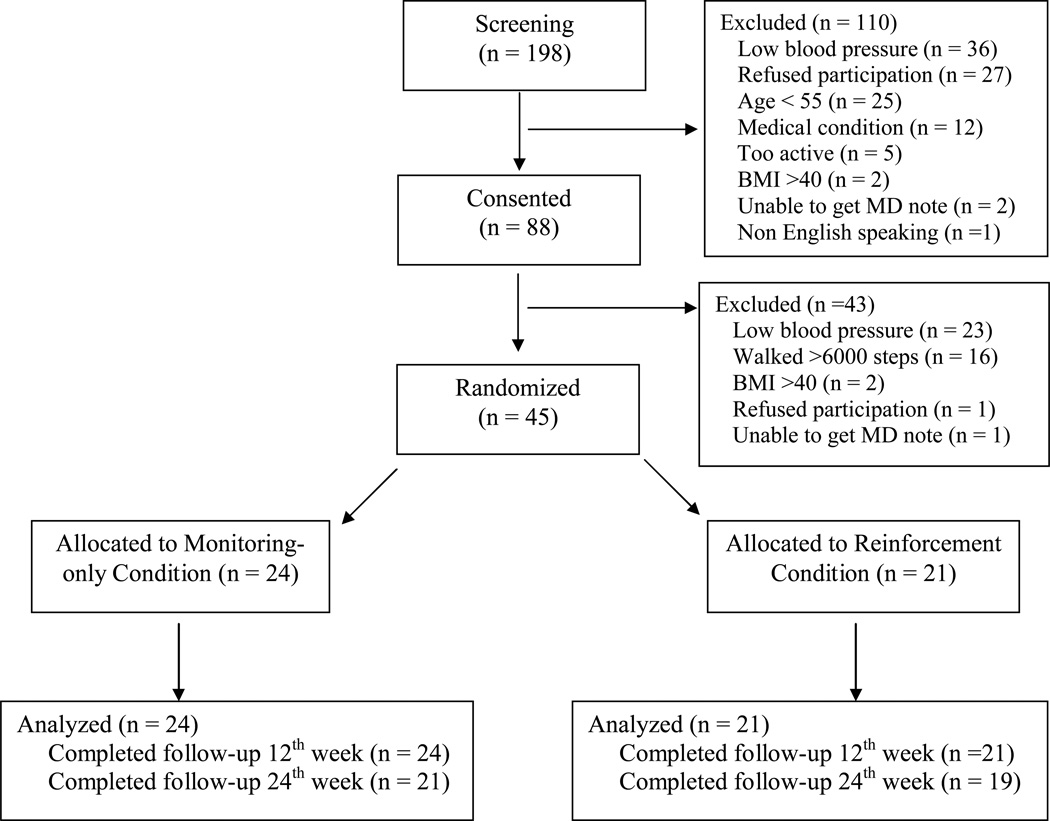

Additional study assessments were also evaluated, including height and weight. Waist circumference was measured at the iliac crest with a Gulick tape measure (Sammons Preston, Chicago, IL). Resting blood pressure (BP) was taken with an Omron automatic monitor (Bannockburn, IL), after at least 5 min of rest. Blood pressure was measured at least twice every 5 minutes, in the non-dominant arm, until consecutive recordings were within 5 mmHg. Some other consented participants were excluded due to not meeting blood pressure (n = 23) or BMI criteria (n = 2), leaving 45 of the 88 consented participants to be randomized. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of participant flow through study procedures.

The Six Minute Walk Test (SMW; Cahalin, Mathier, Semigran, Dec, & DiSalvo, 1996) evaluated distance (in m) covered in 6 min, when walking indoors in a tiled hallway. For the Sit to Stand Test, participants started in a standing position, sat in a chair, then returned to a standing position as quickly as possible, five times in a row (Bohannon, 1995). Time (in sec) was recorded, using the fastest of two trials.

Randomization

Participants (n = 45) meeting all study criteria were randomized to one of two conditions after the second in-person baseline assessment. A computerized urn randomization program (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994) balanced group assignments on mean daily steps (<4,000 steps versus ≥4,000 steps) at baseline.

Attention control

Participants (n = 24) continued to wear pedometers daily and met weekly with staff for 12 weeks. They were encouraged to walk ≥6,000 steps per day in week 1, ≥8,000 steps per day in week 2, and ≥10,000 steps per day for the remainder of the 12-week treatment period (Thompson et al., 2010). At the weekly meetings, which lasted 10–15 minutes, pedometer data were recorded, and participants were congratulated for every day they walked the target number of steps. They were encouraged to problem-solve issues that impacted their ability to meet walking goals. Staff also discussed the health benefits of walking. Participants earned a $5 gift card if pedometer data were registered on the prior 7 days.

Reinforcement

These participants (n = 21) received the same care as above. Additionally, they earned reinforcers for walking at least the target number of steps per day (≥6,000 in week 1, ≥8,000 in week 2, and ≥10,000 in weeks 3–12). At each visit, they earned one draw from a prize bowl for each day they walked the target number of steps. They also earned bonus draws each week that they met the goal on at least 6 days. Bonus draws started at 3 and increased by 3 at each consecutive visit of meeting the target number of steps at least 6 of 7 days up to a maximum of 15 bonus draws per week. If participants failed to walk the target number of steps on more than one day, no bonus was awarded, and bonus draws at the next visit were reset to 3. The maximum number of draws possible was 234. The prize bowl contained 500 slips of paper; 209 stated “small” and were associated with $1 prizes (e.g., choice of toiletries, water bottles, pens, 2 stamps); 40 stated “large” and were valued at $20 (e.g., choice of watches, cameras, gift cards), and one stated “jumbo” and was valued at $100 (e.g., choice of ipod, stereo, gift cards). The other 250 stated, “Good Job!” but did not result in a prize. Participants who completed the requisite number of steps throughout treatment could earn an average of about $468 in prizes.

Post-treatment and follow-up assessments

All participants (100% completion rate) received $20 for participating in a week 12 post-treatment evaluation using instruments outlined earlier. They were also encouraged to continue walking ≥10,000 steps per day, but they no longer had weekly meetings with study staff or reviews of pedometer readings. Approximately 8 days prior to the 24-week follow-up, staff contacted all participants to remind them of the upcoming appointment and ask them to wear the pedometer for seven days before the meeting. Compensation was $20, and follow-up completion rates were 87.5% (21 of 24) for control participants and 90.5% (19 of 21) for reinforcement participants.

Data analysis

Chi-square and t-tests compared groups on baseline characteristics. The primary dependent measure was the proportion of days participants walked the recommended number of steps (≥6000 in week 1, ≥8000 in week 2, and ≥10,000 in weeks 3–12, and at week 24). Using an intent-to-treat approach, an independent groups t-test compared the groups with respect to proportional days step goals were met.

As a secondary outcome, average daily steps were calculated on a weekly basis for the one-week baseline period, each of the 12 intervention weeks, and the week preceding the 24-week follow-up evaluation. Hierarchical linear models (HLM) evaluated changes in this outcome measures, as well as other secondary outcomes (blood pressure, weight, waist circumference, six minute walk test, and sit-to-stand test) from pre-treatment to post-treatment and the week 24 follow-up. These analyses are ideal for repeated measures designs with missing data because participants with missed assessments are not dropped from the analyses, and they utilize actual, as opposed to scheduled, time of assessments (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). They take into account within- (Level-1) and between-participants (Level-2) values for estimating missing data. Partial regression coefficients estimated intercepts and slopes at each level. These models predicted outcome variable Y from the Level-1 predictor (Time) and Level-2 predictor (Group):

| Level-1 Model: | Y = β0 + β1 * (Time) + R |

| Level-2 Model: | β0 = γ00 + γ01 * (Group) + u0 |

| β1 = γ10 + γ11 * (Group) + u1 |

To examine group differences over time, group was coded 0 for the reinforcement condition, so significant effects of Intercept (γ10) indicate that the slope of those receiving reinforcers differed significantly from 0, and significant effects of slope (γ11) reveal that slopes of the two groups differed. Models were re-run with the control condition coded 0 such that significant effects of γ10 indicate changes over time differed significantly from 0 in that condition. Predictor variables were treated as fixed and uncentered, and the final estimation of fixed effects (with robust standard errors) is presented. For average steps per day, data from all randomized participants were included at each time point data were collected, consistent with an intent-to-treat analysis.

For analysis of data from the sit-to-stand test, two outlier values (one at baseline from a control participant, and one at week 24 from a reinforcement participant) were removed from analyses because they were >3 standard deviations above the mean. An a priori decision was made to remove from analyses blood pressure data from participants who altered blood pressure medications during the study period because medication changes can impact blood pressure beyond the effects of walking. Post-treatment and/or follow-up blood pressure data were removed from six participants (three per condition) who altered use, dose, or timing of antihypertensive medications after baseline.

In order to evaluate longer-term improvement of ambulatory activity, univariate analysis of variance were conducted to predict average steps per day at the week-24 follow-up. All 40 participants who completed the week-24 follow-up were included in this analysis, and there were no differences between follow-up completers and non-completers based on baseline characteristics or treatment assignment, ps > .30. Independent variables included gender, age, race, education, baseline weight, baseline average steps per day, and treatment condition. Treatment condition was entered as a random factor, and gender and race (Caucasian vs. other) as fixed factors. Continuous variables (age, education, weight, and baseline steps per day) were included as covariates. Analyses were conducted on SPSS v. 15, with p < .05 significant.

Results

Baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants assigned to the two conditions did not differ significantly with respect to any demographic or baseline characteristic except diastolic blood pressure, which was an average of 5 mmHg higher among those in the reinforcement condition.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics by treatment groups.

| Variable | Attention control (n=24) |

Reinforcement (n=21) |

Statistic (df) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, % (n) | 91.7 (22) | 76.2 (16) | χ2 (1) = 2.04 | .15 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % (n) | 0.0 (0) | 4.8 (1) | χ2 (1) = 1.17 | .28 |

| Race, % (n) | χ2 (2) = 3.67 | .16 | ||

| African American | 0.0 (0) | 9.5 (2) | ||

| Caucasian | 100.0 (24) | 85.7 (18) | ||

| Other | 0.0 (0) | 4.8 (1) | ||

| Taking anit-hypertensive medication, % (n) | 66.7 (16) | 57.1 (12) | χ2 (2) = 0.43 | .51 |

| Age | 63.2 ± 6.6 | 63.2 ± 5.3 | t (43) = .01 | .99 |

| Years of education | 15.8 ± 2.4 | 14.8 ± 2.4 | t (43) = 1.43 | .16 |

| Household income† | 60,000 ± 63,000 | 82,000 ± 68,000 | t (43) = −0.87 | .39 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 128.8 ± 11.7 | 131.9 ± 10.6 | t (43) = −0.96 | .34 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 80.9 ± 6.5 | 85.9 ± 7.5 | t (43) = −2.39 | .02 |

| Weight, pounds | 182.7 ± 38.3 | 203.2 ± 50.8 | t (43) = −1.54 | .16 |

| Waist circumference | 99.5 ± 13.9 | 106.4 ± 20.5 | t (43) = −1.34 | .19 |

| Walked less than 4000 steps per day in baseline week | 37.5 (9) | 57.1 (12) | χ2 (2) = 1.74 | .18 |

Values are means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

= median ± interquartile range; data were log transformed prior to analyses.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in attendance at weekly sessions, with participants assigned to the control intervention attending on average (standard deviation) 10.3 ± 3.0 of the 12 sessions and participants assigned to the reinforcement intervention attending 11.4 ± 1.2 sessions, t (43) = 1.64, p = .11. Of the 84 possible days of pedometer readings, participants in the control condition provided readings on 70.5 ± 21.1 days and participants in the reinforcement intervention on 77.8 ± 9.5 days, t (43) = 1.47, p = .15.

In analyzing proportion of days on which participants met the targeted number of steps, a conservative approach was used with missing data considered “missing” and not included in the denominators (i.e., factoring missing days in the denominator results in lower proportions of days meeting the goal for participants with more missing data). Of days on which steps were registered, the proportion of days on which participants met the targeted number of steps (≥ 6000 in week 1, ≥ 8000 in week 2, and ≥ 10,000 in weeks 3–12) was 55.3% ± 37.1% for the control condition versus 82.5% ± 25.8% for the reinforcement condition, t (43) = 2.82, p = .007. In weeks 3–12, 37.5% (9 of 24) of control participants walked ≥ 10,000 steps ≥50 days (i.e., at least 5 days per week for 10 weeks) versus 81.0% (17 of 21) of reinforcement participants.

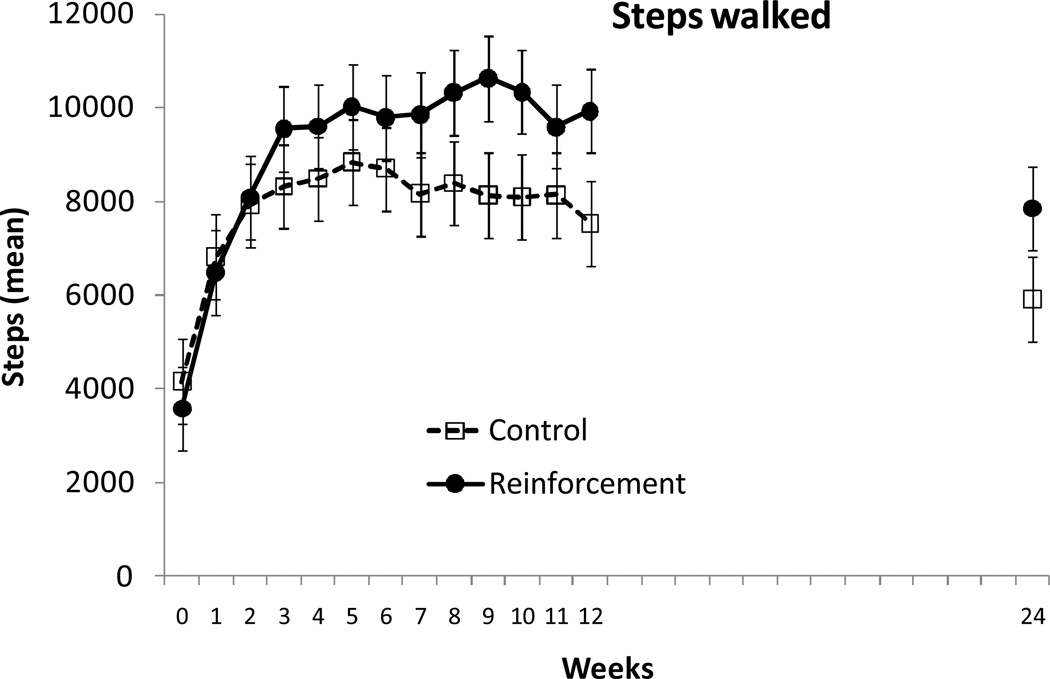

Figure 2 shows average steps per day in the week before randomization, weekly throughout the 12-week treatment period, and at the week 24 follow-up evaluation for participants assigned to the two conditions. HLM analyses revealed that both groups significantly increased walking relative to baseline, and Table 2 shows results of the HLM analyses revealing significant and positive slopes for both groups (ps < .03). However, the slopes of the two groups also differed over time (p < .005), indicating a significantly greater increase in steps in the reinforcement relative to the control condition.

Figure 2.

Average steps per day. Data are plotted for mean steps per day in the week before treatment, throughout each of the 12 weeks of the treatment period, and in the week preceding the 24-week follow-up evaluation. Values represent raw means across the seven days of each one week period. Data from participants assigned to the control condition are shown in open squares, and data from participants assigned to the reinforcement condition are shown in filled circles.

Table 2.

Results from hierarchical linear models analyses of walking, health and fitness indices collected at baseline, week 12 (end of treatment), and week 24 (follow-up).

| β1 coefficient |

Standard error |

T ratio (df = 43) |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steps walked | ||||

| Control | 7.0961 | 3.3132 | 2.14 | .03 |

| Reinforcement | 21.8935 | 3.8831 | 5.64 | .001 |

| Group × time interaction | −14.7974 | 5.1045 | −2.90 | .005 |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||

| Control | −0.0090 | 0.0292 | −0.31 | .76 |

| Reinforcement | −0.0786 | 0.0148 | −5.33 | .001 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.0696 | 0.0327 | 2.13 | .03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||

| Control | −0.0101 | 0.0110 | −0.92 | 0.36 |

| Reinforcement | −0.0468 | 0.0137 | −3.41 | .001 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.0367 | 0.0176 | 2.09 | .04 |

| Weight | ||||

| Control | −0.0108 | 0.0095 | −1.14 | .26 |

| Reinforcement | −0.0414 | 0.0131 | −3.18 | .002 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.0306 | 0.0161 | 1.90 | .05 |

| Waist circumference | ||||

| Control | −0.0134 | 0.0065 | −2.06 | .04 |

| Reinforcement | −0.0286 | 0.0089 | −3.23 | .002 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.0152 | 0.0110 | 1.38 | .17 |

| Six minute walk test | ||||

| Control | −0.0453 | 0.0606 | −0.75 | .46 |

| Reinforcement | 0.1474 | 0.0638 | 2.31 | .02 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.1927 | 0.0880 | 2.19 | .03 |

| Sit-to-stand test | ||||

| Control | 0.3253 | 0.2536 | −1.28 | .20 |

| Reinforcement | −1.1846 | 0.3454 | −3.43 | .001 |

| Group × time interaction | 0.8593 | 0.4285 | 2.01 | .05 |

Notes: Although 43 patients were randomized and included in these analyses, not all participants (n = 3) completed the 24-week follow-up, and extreme outliers were excluded at some time points, or in the case of anti-hypertensive medication changes for blood pressure data (see methods section). β1 coefficients represent the slopes, and slopes with p values < .05 are significantly different from 0 (i.e., reflect significant changes in slope over time). When group × time interaction effects are significant (p < .05), the slopes of the two conditions differ.

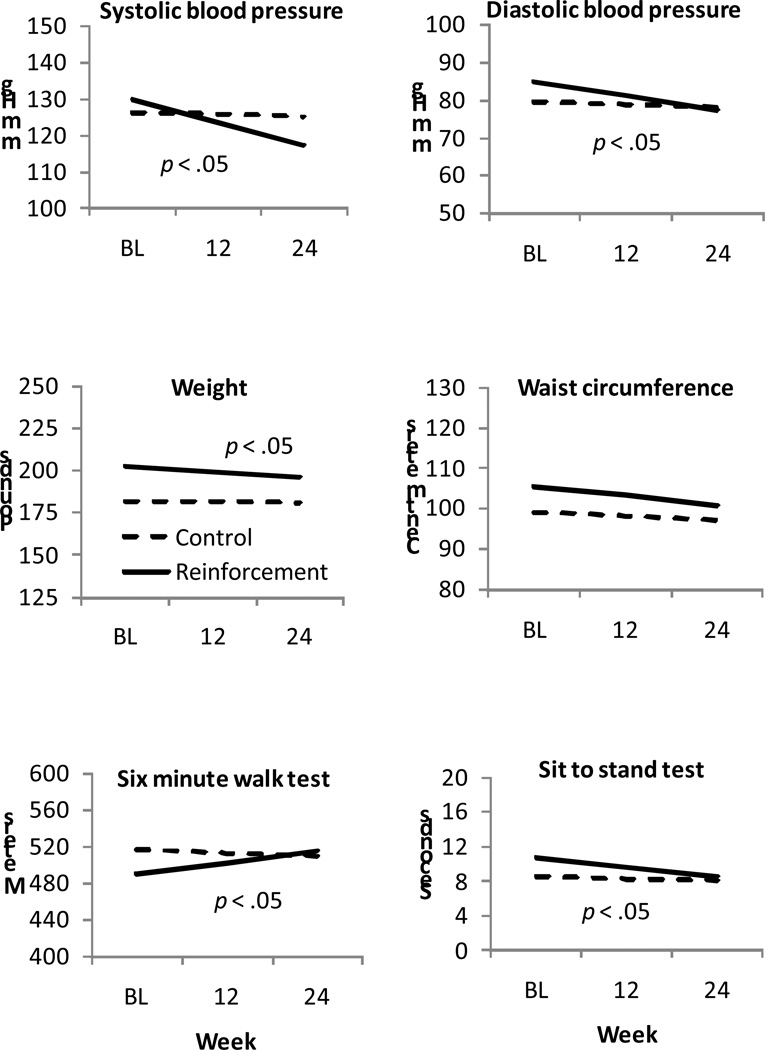

Figure 3 (top panels) shows blood pressure data over time, and Table 2 shows results from the HLM analyses of these data. No changes in blood pressure were noted over time in the control condition (ps > .35 for both systolic and diastolic blood pressure). In contrast, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased significantly over time in the reinforcement condition (ps < .001), and the group by time interaction effects were significant (ps < .05).

Figure 3.

Physiological assessments and fitness indices over time by treatment condition. Data are derived from hierarchical linear models analyses as described in the text, and represent group means. Data from participants assigned to the control condition are shown by dashed lines, and data from participants assigned to the reinforcement condition are shown by solid lines. The treatment condition by time interaction effect is significant when p < .05.

The middle panels of Figure 3 show bodyweights (left) and waist circumferences (right) over time in participants assigned to the two conditions. Participants in the reinforcement condition showed a significant reduction in weight over the study period (p < .002), while those assigned to the control condition did not (p = .26); the treatment group by time interaction was significant for weight loss (p < .05). Both groups significantly decreased waist circumference over time (ps < .05), and the two slopes did not differ for that variable (p = .17).

The bottom panels of Figure 3 show performance on the six minute walk test and sit-to-stand test. Those assigned to the control condition evidenced no change in performance over time (ps > .20), but slopes increased and decreased, respectively, in those assigned to the reinforcement condition (ps < .02). The group by time interaction effects were significant (ps < .05), indicating differential improvement in performance on both fitness indices in the reinforcement condition.

In predicting average steps per day at the 24-week follow-up, no baseline characteristics were significant, although steps walked at baseline trended toward predicting steps at follow-up. Table 3 shows the results of these analyses. Even after controlling for steps at baseline, treatment condition was a significant predictor of average steps at follow-up, p = .02. Mean steps per day at follow-up was 5,004 ± 1,360 among participants in the control condition and 7,503 ± 1,073 among participants in the reinforcement condition. Results were similar when no covariates were included, and treatment condition remained significantly associated with average steps walked at the 24-week follow-up, F (1,38) = 4.66, p = .04.

Table 3.

Results from a univariate analysis of variance evaluating associations between baseline variables and steps per day at the 24-week follow-up (n = 40).

| Variable | Beta | Standard error | t (32) = | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 351.38 | 1409.85 | 0.25 | .81 |

| Race | −1781.38 | 1955.13 | −0.91 | .37 |

| Age | 40.25 | 84.38 | 0.48 | .64 |

| Years of education | −176.99 | 208.91 | −0.85 | .40 |

| Weight | −1.10 | 11.30 | −0.10 | .92 |

| Mean steps per day at baseline | 0.86 | 0.44 | 1.97 | .06 |

| Treatment condition | −2498.58 | 1049.40 | −2.38 | .02 |

Notes: For gender, female was coded 1 and male coded as 0. For race, white was coded 1 and all others as 0. For treatment condition, the reinforcement condition was coded as 1 and the attention control condition as 0. Patients who did not complete the 24-week follow-up (n = 3) were not included in this analysis.

Participants assigned to the reinforcement intervention earned an average of 175 ± 71 draws, resulting in $375 ± $172 worth of prizes (range $2 to $681). There were no study-related adverse events.

Discussion

Reinforcing walking in older adults resulted in substantial increases in ambulatory activities, and participants assigned to the reinforcement condition met walking goals (i.e., walked over 10,000 steps per day) on 83% of days compared with only 55% of days among participants assigned to the control condition. Throughout the 12-week intervention period, mean steps walked per day were 7,853 for those assigned to the reinforcement condition versus 5,913 for those assigned to the control condition. At baseline, participants were sedentary, and they had activity levels consistent with national norms for older adults (Basset et al., 2010). Participants in this study were self-selected, so all had some desire to increase walking. Attendance at the weekly sessions was good, with over 85% of sessions attended. This high rate of participation may have resulted from enrolling only individuals who desired to increase walking, or because attendance was modestly compensated ($5/session) to ensure availability of pedometer data.

Benefits of reinforcing walking appeared to extend to health and fitness indices. Participants who were reinforced for increasing ambulatory activity had reductions in weight and blood pressure, with an average 14 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure and a 7 pound weight loss relative to baseline. They also showed improvements on the six minute walk and sit-to-stand tests. In contrast, changes on these indices were not significant in those assigned to the control condition. These effects speak to potential health benefits of tangibly reinforcing activity levels, although they should be interpreted cautiously due to the number of tests conducted on secondary outcome measures.

Importantly, this study also found that effects of the intervention persisted beyond the period during which reinforcers were in effect. Twelve weeks after treatment ended, participants who had received reinforcement earlier continued to walk an average of 2,000 more steps per day than their counterparts who never received reinforcement. Similarly, some health and fitness indices appeared to show continued improvements after reinforcement ceased.

Although this study demonstrated some positive effects that persisted for 24 weeks, even longer term follow-up evaluations would be useful. Psychological processes were not assessed in this study, but evaluation of psychological mechanisms (e.g., motivation to change, self efficacy to exercise) may provide insight about the mechanisms of short- and long-term behavioral change. These results are also limited by the small sample size and primarily female and Caucasian sample, and the effects may not generalize to more diverse populations. Participants assigned to the reinforcement condition had significantly higher diastolic blood pressures at baseline, representing a randomization failure which is more likely with small sample sizes such as these. Therefore, reductions in diastolic blood pressure over time may represent a regression toward the mean, and these results should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, five of six health and fitness indices showed benefits in the direction of improvement with the reinforcement intervention.

The post-treatment data indicate that while effects of the reinforcement intervention were still statistically significant 12 weeks after the intervention ended, the average number of steps declined to below the recommended guidelines of 10,000 steps per day (USDHHS, 2008). Thus, uncovering methods to maintain even higher rates of walking following reinforcement interventions would be useful. Providing booster reinforcers at gradually decreasing intervals may assist in maintaining behavioral changes.

These promising data suggest that additional studies of reinforcement interventions for increasing physical activity levels in older adults are warranted. Inclusion of more sensitive indices of activity levels such as accelerometers may be useful in more carefully quantifying the type of activity levels. Further evaluation of health parameters (e.g., cholesterol, bone density) may reveal other benefits of reinforcing active lifestyle changes.

If reliably efficacious in enhancing ambulatory activity levels, policy decisions will be needed to guide expansion of reinforcement interventions clinically. Cost benefit analyses, for example, may determine that providing up to $500 in reinforcers to encourage high rates of ambulation over a 12-week period ultimately may translate to overall reductions in health care costs, especially in vulnerable populations such as older adults. Such analyses may also reveal that even greater magnitudes or longer duration interventions may generate significant cost savings (Wang, Pratt, Macera, Zheng, & Heath, 2004). Already, some insurers and up to 25% of employers (Linnan et al., 2008) are providing incentives for individuals participating in health promotion campaigns, but many of these programs do not follow basic behavioral principles and have not been evaluated with respect to efficacy. These efforts, nevertheless, suggest that reinforcement interventions are gaining traction with insurers and perhaps the public as well. Scientific study is needed to ascertain how best to implement and measure the impact of reinforcement interventions on health-related behaviors as well as the populations that may be best served by them.

Acknowledgments

This research and preparation of this report was supported in part by NIH grants P30-DA023918, R01-DA027615, R01-DA022739, P50-DA09241, T32-AA07290, DP3-DK097705, T32-AA07290, and M01-RR06192. We thank Amy Novotny for her dedicated assistance in conducting this study.

References

- Anderson RE, Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Zemel B, Verde TJ, Franckowiak SC. Effects of lifestyle activity vs. structured aerobic exercise in obese women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:335–340. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett DR, Wyatt HR, Thompson H, Peters JC, Hill JO. Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in United States adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2010;42:1819–1825. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW. Sit-to-stand test for measuring performance of lower extremity muscles. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1995;80:163–166. doi: 10.2466/pms.1995.80.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, Gienger AL, Lin N, Lewis R, Sirard JR. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review. Journal of the American Model Association. 2007;298:2296–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Radonovich KJ, Novy PL. Adding voucher-based incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1051–1061. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LE, Dunba-Jacob JM, Hill MN. Compliance with cardiovascular disease prevention strategies: A review of the research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19:239–263. doi: 10.1007/BF02892289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butsch WS, Ard JD, Allison DB, Patki A, Henson CS, Rueger MM, Heimburger DC. Effects of a reimbursement incentive on enrollment in a weight control program. Obesity. 2007;15:2733–2738. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalin LP, Mathier MA, Semigran MJ, Dec G, DiSalvo T. The six-minute walk test predicts peak oxygen uptake and survival in patients with advanced heart failure. Chest. 1996;110:325–332. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J, Banko KM, Pierce WD. Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. Behavior Analysis. 2001;24:1–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03392017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo CJ, Keteyian SJ, Heath GW, Sempos CT. Leisure-time physical activity among US adults. Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1996;156:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcer magnitude. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day L, Fildes B, Gordon I, Fitzharris M, Flamer H, Lord S. Randomized factorial trial of falls prevention among older people living in their own homes. British Medical Journal. 2002;325(7356):128. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca RV, Holborn SW. Effects of a variable-ratio reinforcement schedule with changing criterion exercise in obese and nonobese boys. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:671–679. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:627–668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Sallis JF, Orenstein DR. The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Reports. 1985;100:158–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Thompson JK, Wing RR, Griffin W. Attendance and fitness in aerobics exercise. Behavior Modification. 1980;4:465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB, Skinner BF. Schedules of Reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Brown DS, Brown DR, Buchner DM. A randomized study of financial incentives to increase physical activity among sedentary older adults. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. Physical activity and inactivity in an adult population assessed by accelerometry. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2007;39:1502–1508. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180a76de5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim AA, Curb JD, Petrovitch H, Rodriguez BL, Yano K, Ross GW, Abbott RD. Effects of walking on coronary heart disease in elderly men: The Honolulu heart program. Circulation. 1999;100:9–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau ML, Fischer J. Self-modification of exercise behavior. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1974;5:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Blumenthal JA. The life fitness program: A behavioral approach to making exercise a habit. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1980;11:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Petry NM. Does contingency management affect motivation to change substance use? Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2006;9:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke SE, Gallo LC, Norman GJ. Attrition and adherence rates of sustained vs. intermittent exercise interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J, Lindsay G, Blakey C, Pronk S, Royall P. Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1503–1509. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PJ, Collins CE, Plotnikoff RC, Cook AT, Berthon B, Mitchell S, Callister R. Efficacy of a workplace-based weight loss program for overweight male shift workers: The workplace POWER (Preventing Obesity without Eating like a Rabbit) randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine. 2011;52:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau KL, Degarmo R, Langley J, McMahon C, Howley ET, Bassett DR, Thompson DL. Increasing daily walking lowers blood pressure in postmenopausal women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33:1825–1831. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville BH, Merrill RM, Kumpfer KL. Longitudinal outcomes of a comprehensive, incentivized worksite wellness program. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2011;34:103–123. doi: 10.1177/0163278710379222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin JA, Grace RC. Behavioral momentum and the law of effect. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2007;23:73–90. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00002405. discussion 90–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Petry NM. Contingency Management for Substance Abuse Treatment: A Guide to Implementing this Evidence-based Practice. New York: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Barry D, Pescatello L, White WB. A low-cost reinforcement procedure improves intermediate-term weight loss outcomes. American Journal of Medicine. 2011;124:1082–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kolodner KB, Li R, Pierce JM, Roll JR, Stitzer ML, Hamilton JA. Prize-based contingency management does not increase gambling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Rash CJ, Byrne S, Ashraf S, White WB. Financial reinforcers for improving medication adherence: Findings from a meta-analysis. American Journal of Medicine. 2012;125:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohaska T, Belansky E, Belza B, Buchner D, Marshall V, McTigue K, Wilcox S. Physical activity, public health, and aging: Critical issues and research priorities. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:S267–273. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.s267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CR, Newton TL, Abraham JJ, Sen A, Jimbo M, Swartz AM. A meta-analysis of pedometer-based walking interventions and weight loss. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6:69–77. doi: 10.1370/afm.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M, Dieckhaus K, McMahon T, Valdes B, Petry N, Cramer J, Rounsaville B. Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:30–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar JL. Paying for performance: The power of incentives over habits. Health Economics. 2008;17:449–451. doi: 10.1002/hec.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout R, Wirtz R, Carbonari J, Del Boca F. Ensuing balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. USDHHS, Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2008. www.health.gov/paguidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel T, Brechat PH, Leprêtre PM, Kaltenbach G, Berthel M, Lonsdorfer J. Health benefits of physical activity in older patients: A review. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2009;63:303–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KGJ, Troxel LK, Norton AB, Fassbender L, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Pratt M, Macera CA, Zheng ZJ, Heath G. Physical activity, cardiovascular disease, and medical expenditures in U.S. adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:88–94. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki T, Hall G, Iwata B, Riordan M. Behavioral management of exercise: Contracting for aerobic points. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979;12:55–64. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]