Abstract

Although relief of postoperative pain is an imperative aspect of animal welfare, analgesics that do not interfere with the scientific goals of the study must be used. Here we compared the efficacy of different analgesic agents by using an established rat model of supraspinatus tendon healing and a novel gait-analysis system. We hypothesized that different analgesic agents would all provide pain relief in this model but would cause differences in tendon-to-bone healing and gait parameters. Buprenorphine, ibuprofen, tramadol–gabapentin, and acetaminophen were compared with a no-analgesia control group. Gait measures (stride length and vertical force) on the operative forelimb differed between the control group and both the buprenorphine (2 and 4 d postsurgery) and ibuprofen (2 d postsurgery) groups. Step length was different in the control group as compared with the tramadol–gabapentin (2 d after surgery), buprenorphine (2 and 4 d after surgery), and ibuprofen (2 d after surgery) groups. Regarding tendon-to-bone healing, the ibuprofen group showed less stiffness at the insertion site; no other differences in tendon-to-bone healing were detected. In summary, the analgesics evaluated were associated with differences in both animal gait and tendon-to-bone healing. This information will be useful for improving the management of postsurgical pain without adversely affecting tissue healing. Given its ability to improve gait without impeding healing, we recommend use of buprenorphine for postsurgical pain management in rats. In addition, our gait-analysis system can be used to evaluate new analgesics.

The relief of postprocedural pain and distress is an imperative aspect of animal welfare. However adequate analgesia must be achieved without adverse effects on the goals of the study. Therefore, the detection and management of pain in animal research models is continually being studied and refined. Postprocedural pain is a complex process that involves hypersensitivity and hyperalgesia to several stimuli.8,9,19,32,68 Furthermore, surgical procedures can cause pain through inflammation and the manipulation and damage of tissues.1 Several methods for evaluating postprocedural pain in rodents involve variably subjective scoring systems and assessment of in-cage locomotor and behavior activity, hypersensitivity to stimuli, or observing food and water intake.37,39,43,53-55,61,63 An objective functional assessment test may provide a more reliable and quantifiable way to measure postoperative pain.

Several rodent models to study musculoskeletal injuries are currently being used in biomedical research,6,29,34 including a well-established rat model for rotator cuff injury.49,51,56,60 This surgical model involves considerable injury to and manipulation of both bone and soft tissues. Because “it should be considered that procedures that cause pain in humans may also cause pain in vertebrate species,” it is clear that this model would also serve as a good model for significant postprocedural pain.27,40,65 The objective of the current study was to compare the efficacy of different analgesic agents by using an established rat model for supraspinatus tendon healing and a novel gait-analysis system.56

We assessed different classes of analgesics, which we chose to represent common recommendations for postprocedural care. Buprenorphine is one of the most commonly used analgesics in laboratory animal medicine due to its proven analgesic qualities in rodents and other species.13,17,25,26,58 However, its status as a controlled substance may limit its use, and other options may be desirable. NSAID are often chosen for the management of postprocedural analgesia in both rodents and humans.16,25,26,38 Because ibuprofen is used frequently after tendon repair in human medicine, we selected it for analysis in the current study. Due to the ease of administration, putting analgesics like acetaminophen in the drinking water of rodents has been a popular suggestion recently.4,17,62 However, numerous studies have found variation in analgesic efficacy in rodents using acetaminophen in the drinking water.11,33,45,50,64 Finally, a tramadol–gabapentin combination was recently reported to have some analgesic effects in rats, but additional research is required.44

A secondary goal of the current study was to determine whether these commonly used analgesics affect tendon-to-bone healing. NSAID may have adverse effects on tendon healing,10,14 but these are far less studied than are their effects on the healing of bone.21,41,59 In addition, pain may influence cage activity levels, which consequently could change with the application of analgesics.35,39,53 Increased activity may alter loads on the healing tissue as well as joint mobility, thus affecting tendon healing.7,24,47,69

In the current study, we used various spatial, temporal, and force parameters to analyze gait in the rat model of rotator cuff healing. In other species, pain in a forelimb decreases stride length, limb speed, and gait forces.28,31,36,46 We expected to find similar changes in the gait of rats after surgery when analgesia is inadequate. Our custom gait-analysis system allowed us to measure several parameters, which were compared between treated and control groups to determine whether significant differences occurred. We used biomechanical testing procedures to determine how changes in tendon-to-bone healing after repair differed among the various analgesics. The weakest point of the tendon is the healing site, because of the development of new immature tissue, and changes in the mechanical properties of the repaired tendon indicate alterations in healing. Therefore, poor healing leads to decreases in the mechanical properties of the repaired tendon.22,23 We hypothesized that the different analgesics evaluated all would provide pain relief in this model but would demonstrated differences in tendon-to-bone healing and in gait parameters compared with those of a no-analgesia control group.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The University of Pennsylvania IACUC approved all procedures used in this study. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Rattus norvegicus; n = 50; weight at acquisition, 400 to 450 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were assigned randomly to 1 of 5 analgesic groups (n = 10): control with no analgesia; oral ibuprofen; tramadol and gabapentin injections; buprenorphine injections; and flavored acetaminophen in the drinking water. Rats were housed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals27 in an AAALAC-accredited facility on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle at a density of 2 rats per static polycarbonate microisolation cage (Rat Cage, Alternative Design, Siloam Springs, AR) containing disposable bedding (0.12-in.-diameter Bed-O-Cobs, Animal Specialties and Provisions, Quakertown, PA). Wire-lid food hoppers in cages were filled to capacity with rodent chow (LabDiet 5001, Animal Specialties and Provisions), and rats were maintained on water supplied by bottle. Rats were housed in rooms with sentinel rats that were exposed to soiled bedding and that were tested during 3 quarters by serology according to the Prevalent panel (Charles River Laboratories). Live sentinels are sent submitted annually for testing by using the HM Prevalent profile (Charles River Laboratories). Sentinels were negative for common pathogens.

Analgesic dosing.

All doses for analgesics were determined from previously published literature.13,30,42,44,45,57,67 Rats receiving either tramadol (10 mg/kg IP; Wedgewood Pharmacy, Swedesboro, NJ) or buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg SC; Buprenex, Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Limited, Hull, England) were given a preoperative dose and a subsequent dose 6 h later. Buprenorphine and tramadol were given every 8 to 12 h thereafter for 5 d after surgery. A modified version of a published method for training rats to voluntarily accept oral medication3 was used for ibuprofen (Actavis Mid Atlantic, Lincolnton, NC); rats received 20 mg/kg PO preoperatively and then every 8 to 12 h for 5 d after surgery. Rats receiving tramadol also received gabapentin (80 mg/kg SC; Wedgewood Pharmacy) preoperatively and then every 24 h for 5 d postsurgery. Animals receiving acetaminophen (Assured Children's Acetaminophen Liquid, Bio-pharm, Levittown, PA) were allowed free access to cherry-flavored acetaminophen-treated drinking water (concentration, 4.48 mg/mL). To minimize the effects of neophobia, the treated water was given to rats starting 48 h prior to the surgical procedure;4,62 acetaminophen-treated water was continued for 5 d after surgery. Rats received analgesics 2 to 3 h before gait analysis. The control group received surgery with no analgesics.

Surgical procedure.

Rats underwent unilateral supraspinatus detachment and repair surgeries of the left forelimb.5,66 Briefly, a 2-cm skin incision was made over the craniolateral aspect of the scapulohumeral joint, and the supraspinatus was exposed by externally rotating the humerus. The supraspinatus was grasped by using a 5-0 polypropylene suture (Surgipro II, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) in a modified Mason-Allen technique and detached sharply from its insertion site on the greater tuberosity. A tunnel was made transversely through the proximal part of the humerus by using a 0.5-mm drill (Multipro 395, Dremel, Mt Prospect, IL). Any soft tissue remaining at the insertion was removed by using a 1/16-in. burr (Multipro 395, Dremel).The suture placed in the tendon was passed through the tunnel, and the tendon was reattached to the insertion site. Muscle layers were closed with 4-0 polyglactin 910 (Vircryl, Ethicon, Bridgewater, NJ), and the skin was closed by using skin staples. Rats were allowed unrestricted cage activity after the procedure. Rats were weighed and observed before and daily for 10 d after the surgical procedure to assess their health and wellbeing.

Gait analysis.

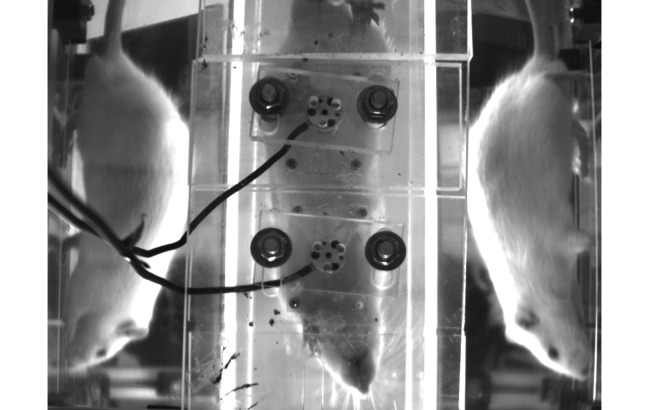

An instrumented walkway was used to quantify forelimb gait and ground reaction forces (Figure 1).56 Rats were placed in the walkway prior to surgery to familiarize them with the environment. Furthermore, before data collection, rats were allowed to become comfortable with and explore the gait analysis system freely. Data were captured only after rats were moving freely between both ends of the walkway, in an attempt to avoid capturing data from rats that might be compensating due to the fear of being in a novel environment. Data were collected on days 2, 4, 6, 14, and 28 after tendon-detachment surgery. Ground reaction force data for the operative limb were collected at each time point and included medial–lateral, braking, propulsion, and vertical forces. In addition, rate of loading was calculated as the vertical force divided by stance time. Temporal and spatial parameters were measured by using pawprint analysis and included stride length, step length, and speed. Stride length is defined as the distance between the first paw placement of the operative limb and the subsequent paw placement of that limb. Step length is defined as the distance between the paw placement of the operative limb and the contralateral limb in the forward direction. At each time point, at least 2 walks were recorded for each rat, in addition to its body weight. Parameters were averaged across walks and normalized to the body weight for each time point.

Figure 1.

Rats were allowed to freely walk through a custom gait analysis system. Two force plates in the center of the image registered forces exerted by individual limbs. Mirrors on each side allow for better visualization of limb placement. The right forelimb is isolated on the second force plate in this image.

Biomechanical testing of tendons.

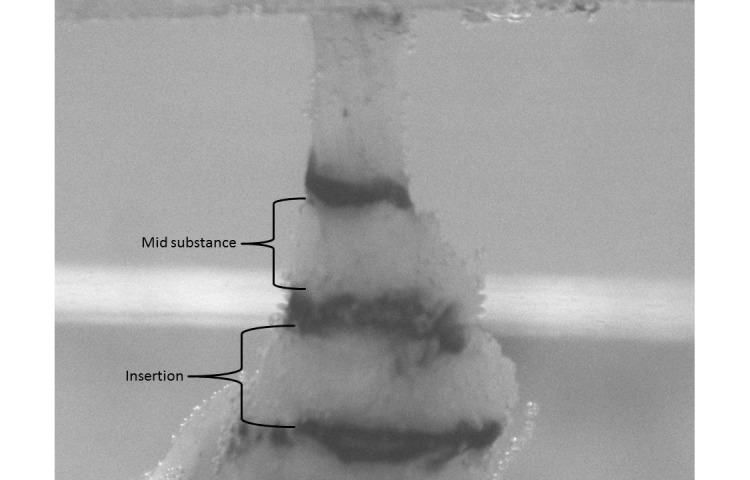

Rats were euthanized on day 29 after surgery and were frozen (−20 °C) until supraspinatus tendon harvest per standard protocol.5,48 The day before testing supraspinatus tendons were dissected free from all surrounding tissue, leaving the insertion to the humerus intact. The bone–tendon units then were removed, and all soft tissue other than the supraspinatus tendon was fine-dissected from surrounding connective tissue. The same person performed all of the dissections and was blinded to the group allocation of all samples. Stain lines were used to track localized tendon strain optically (insertion site and midsubstance) and were placed on the tendon at 1, 2, 4, and 8 mm from the insertion site by using Verhoeff stain. A custom laser device was used to measure the cross-sectional area of the tendons after the stain lines were applied.15 The humerus was embedded in a holding fixture by using polymethylmethacrylate (Ortho Jet, Lang Dental Manufacturing, Wheeling, IL). Tissues were allowed to sit in a refrigerated PBS bath overnight. The next day, tendons were fixed between 2 layers of sandpaper by using an adhesive (Loctite, Henkel, Rocky Hill, CT) and clamped between custom metal grips. The potted tissues were placed in a 37 °C PBS bath and tensile-tested by using a mechanical test frame (model 5543, Instron, Norwood MA) according to previously described protocols (Figure 2).5,14 Tendons underwent 10 preconditioning cycles, followed by a stress–relaxation and ramp-to-failure tests. Images were acquired during ramp to failure at a rate of 2 frames per second. Custom MatLab software (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) was used to calculate optical strain and to determine several mechanical properties (percentage relaxation, maximal load, maximal stress, stiffness, and elastic modulus).

Figure 2.

Supraspinatus tendon in a PBS bath. The humeral head is placed in PMMA (bottom of the image), and the free end of the tendon is gripped in a custom steel device (top of the image). The grip is attached to a load cell and Instron device, which applies tensile forces on the tendon.

Statistics.

Two-way (group and time) ANOVA with repeated measures on time was used to assess the ambulation data. Follow-up t tests were conducted when a significant interaction effect was present, to determine where the significant interaction occurred. Because of lack of compliance by rats, data (approximately 4%) for a specific animal on a specific day occasionally were missing; multiple imputations therefore were conducted to allow for a rigorous repeated-measures analysis. Multiple imputations were conducted by using the standard Markov chain Monte Carlo method. The average of 5 imputations was used for the final analysis. Tendon mechanics were assessed by using an unpaired one-tailed t test. Because of multiple comparisons, Bonferroni corrections were performed by defining significance as a P value of less than 0.0125. SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Gait analysis data.

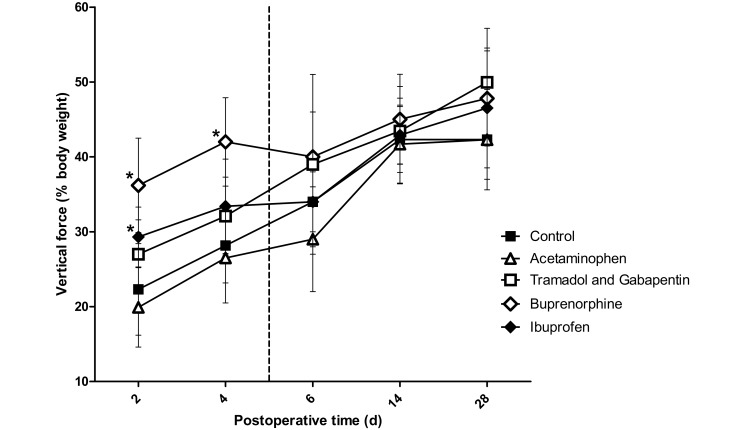

A significant (P = 0.01) vertical force × time interaction effect was identified (Figure 3). Post hoc t tests demonstrated that at 2 d after surgery, forces were significantly higher in the buprenorphine (P < 0.001) and ibuprofen (P = 0.008) groups than in the control group. In addition, vertical force in the buprenorphine group differed (P = 0.007) from that of the ibuprofen group. Force on postoperative day 2 did not differ (P = 0.066) between the tramadol–gabapentin and control group but did differ (P < 0.001) between the tramadol–gabapentin and buprenorphine groups. At 4 d after surgery, force differed significantly (P < 0.001) only between the buprenorphine and control groups. As expected, no differences were noted between groups at 6 d after surgery and later, because analgesic dosing had been completed by those time points.

Figure 3.

Vertical force registered on the force plate by the left forelimb (operative limb). The vertical dashed line represents the final day on which rats received analgesics. Ibuprofen and buprenorphine groups differed significantly from the control group on postoperative day 2. Only the buprenorphine group was statistically different from the control on day 4 postoperative. The increased forces in the ibuprofen and buprenorphine groups on day 2 can be interpreted as increased use of the operative limb due to adequate analgesia. Buprenorphine was the only agent that achieved significantly increased analgesia on postoperative day 4. *, Value significantly (P ≤ 0.0125) different from that of the control group (n = 10); bar, 1 SD.

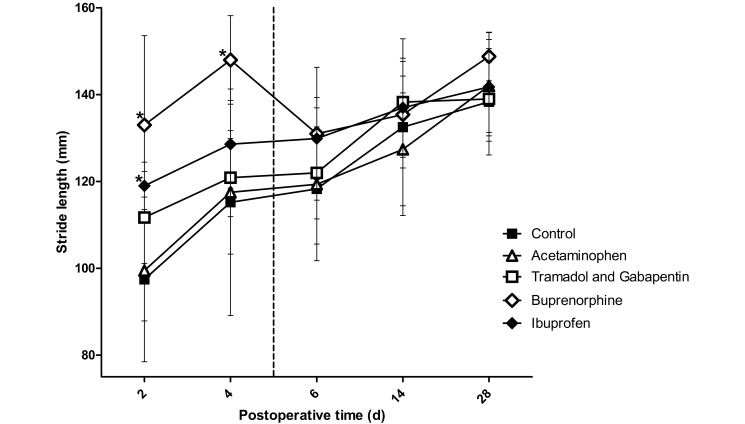

A significant (P = 0.003) stride × time interaction was present (Figure 4). Post hoc t tests demonstrated that at 2 d after surgery, stride length was significantly longer in the buprenorphine (P < 0.001) and ibuprofen (P = 0.002) groups than in the control group. Rats in the tramadol–gabapentin group differed (P = 0.002) only compared with those in the buprenorphine group. At 4 d after surgery, stride length differed (P < 0.001) significantly only between the buprenorphine and control groups. No differences in stride length were noted between groups at 6 d after surgery or later.

Figure 4.

Stride length of the left forelimb (operative limb). The vertical dashed line represents the final day on which rats received analgesics. The ibuprofen and buprenorphine groups differed significantly from the control group on postoperative day 2; only the buprenorphine group was statistically different from the control on day 4. The increased stride length in the ibuprofen and buprenorphine groups on day 2 can be interpreted as increased use of the operative limb due to adequate analgesia. Buprenorphine was the only agent achieving significantly increased of analgesia on postoperative day 4. *, Value significantly (P ≤ 0.0125) different from that of the control group (n = 10); bar, 1 SD.

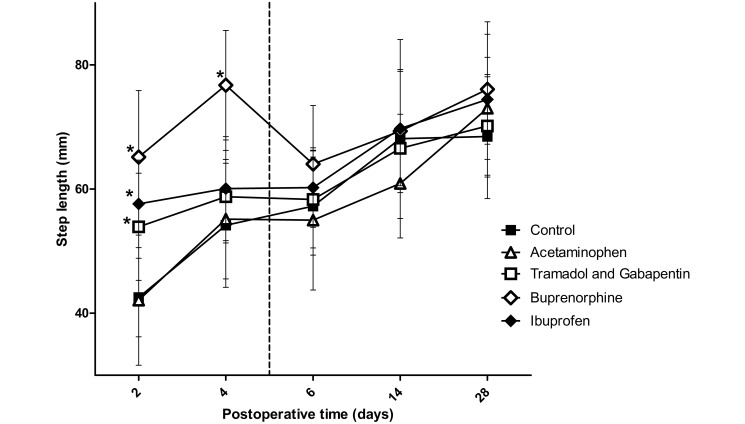

A significant (P < 0.001) interaction effect was found between analgesic groups for step length (Figure 5). Post hoc t tests demonstrated that at 2 d after surgery, rats in the buprenorphine (P < 0.001), ibuprofen (P < 0.001), and gabapentin–tramadol (P = 0.007) groups had longer step lengths than did the control group. At 4 d after surgery, step length differed (P < 0.001) only between the buprenorphine and control groups. No differences were noted between groups at 6 d postsurgery or later.

Figure 5.

The step length between the left forelimb (operative limb) and right forelimb. The vertical dashed line represents the final day rats received analgesics. Significant differences from the control group were found in the ibuprofen, buprenorphine, and tramadol–gabapentin groups on postoperative day 2, but only the buprenorphine group was statistically different from the control on postoperative day 4. The increased step length in the ibuprofen, buprenorphine, and tramadol–gabapentin groups on day 2 can be interpreted as increased use of the operative limb due to adequate analgesia. Buprenorphine was the only agent achieving significantly higher state of analgesia on postoperative day 4. *, Value significantly (P ≤ 0.0125) different from that of the control group (n = 10); bar, 1 SD.

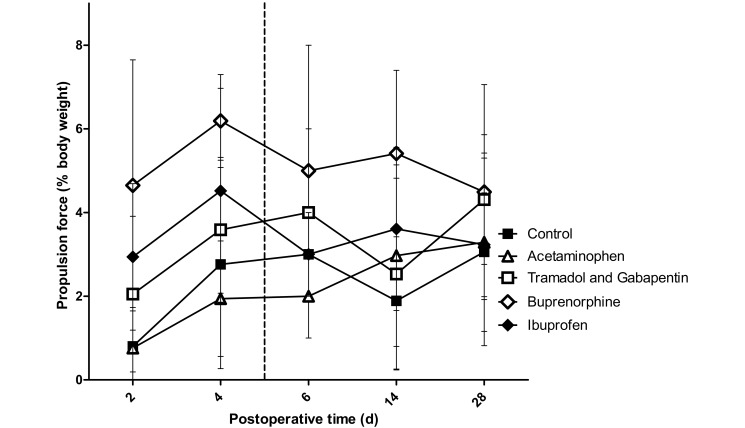

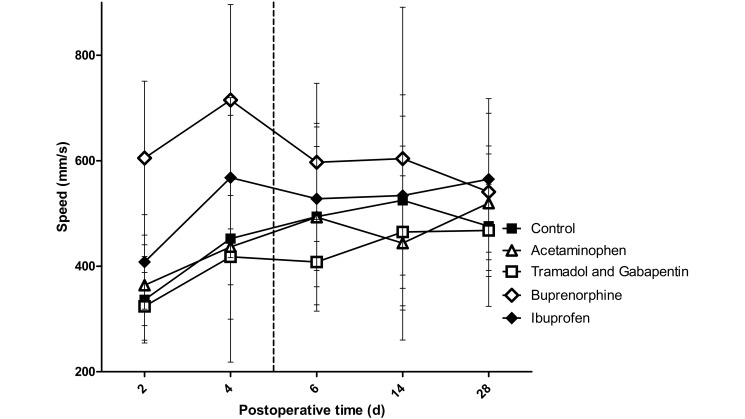

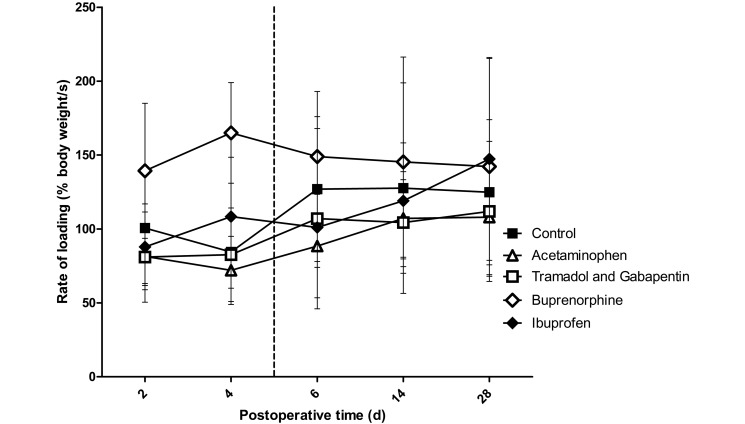

No interaction effects were found for propulsion forces, rate of loading, or operative limb speed, but a significant main effect for group was found. Compared with control rats, those treated with buprenorphine showed differences in propulsion force (P < 0.001), rate of loading (P = 0.006), and operative limb speed (P < 0.001; Figures 6 through 8). There was a trend toward higher propulsion forces for the ibuprofen (P = 0.062) and tramadol–gabapentin (P = 0.065) groups compared with the control group. Operative limb speed did not differ between the ibuprofen and control or buprenorphine groups. In addition, no differences were found among any groups for braking and medial–lateral forces, stance width, or unaffected limb speed.

Figure 6.

Propulsion forces of the left forelimb (operative limb) registered by the force plates. The vertical dashed line represents the final day on which rats received analgesics. No interaction effect was noted; however a significant group effect was noted, with the buprenorphine group being significantly (P ≤ 0.0125; n = 10) different from the control group. This finding indicates that the buprenorphine group was the only group achieving a state of analgesia at which propulsion forces were increased. Bar, 1 SD.

Figure 8.

Speed of the left forelimb (operative limb). The vertical dashed line represents the final day on which rats received analgesics. No interaction effect was noted; however a significant group effect was found, with the buprenorphine group being significantly (P ≤ 0.0125; n = 10) different from the control group. This finding indicates that the buprenorphine group was the only group that achieved a state of analgesia, as demonstrated by the operative limb being used at a faster pace. Bar, 1 SD.

Figure 7.

The rate of loading of the left forelimb (operative limb) registered by the force plates. The vertical dashed line represents the final day on which rats received analgesics. No interaction effect was noted; however, a significant group effect was noted, with the buprenorphine group being significantly (P ≤ 0.0125; n = 10) different from the control group. This finding indicates that the buprenorphine group was the only group that achieved a state of analgesia at which the rate of loading for the operative limb was increased. Bar, 1 SD.

On day 2 after surgery, 3 rats in the acetaminophen group and 4 rats in the control group exhibited nonweight-bearing lameness of the operative limb during gait analysis. On day 4 after surgery, 2 rats in the acetaminophen group demonstrated nonweight-bearing lameness of the operative limb during gait analysis. None of the rats in the other groups had nonweight-bearing lameness of the operative limb at any time point.

Tendon properties.

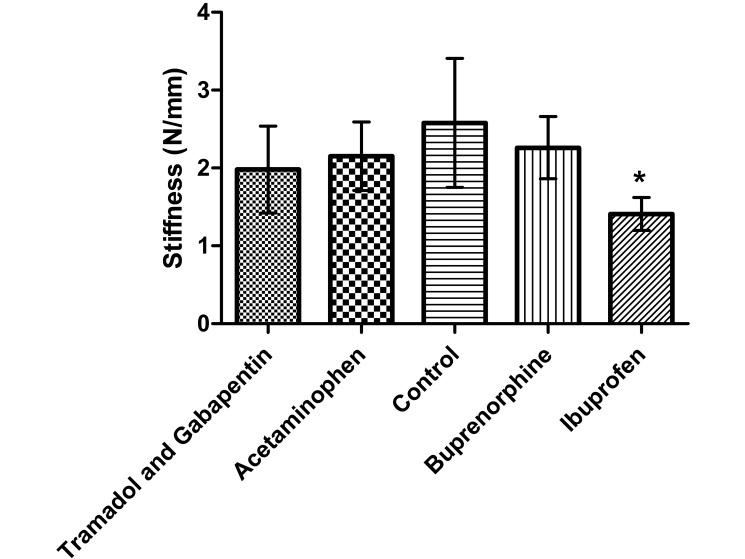

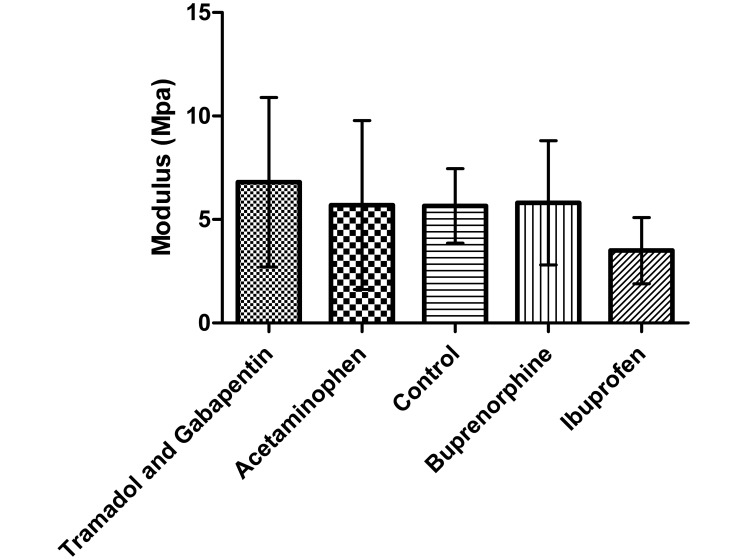

Tendon stiffness was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the ibuprofen group compared with the control group (Figure 9); stiffness did not differ between any other groups. Modulus (Figure 10), maximal failure load, and percentage relaxation (data not shown) were similar among all groups.

Figure 9.

Stiffness of the supraspinatus tendon. Stiffness was lower (*, P ≤ 0.0125) in the ibuprofen group than the control group (n = 10). This reduced tendon stiffness in the ibuprofen group is indicative of decreased tendon-to-bone healing. Bar, 1 SD.

Figure 10.

Modulus of the supraspinatus tendon at the insertion (repair) site at the humeral head. No significant differences were found between any group and the control group (n = 10). Bar, 1 SD.

Animal weights.

Both the control and acetaminophen groups demonstrated decreases from baseline body weight on days 2 and 4 after surgery (Table 1), but both groups gained weight compared with baseline on day 6 after surgery. Rats in the buprenorphine, tramadol–gabapentin, and ibuprofen groups maintained or gained weight through day 2 after surgery; only the ibuprofen group had a weight gain on day 6 after surgery. Both the buprenorphine and tramadol–gabapentin groups lost weight relative to baseline on day 6 after surgery. All groups gained weight during the subsequent weeks.

Table 1.

Body weight of rats in each group (n = 10)

| Weight (g; mean ± 1 SD) |

||||||

| Before surgery | Time after surgery |

|||||

| Group | 2 d | 4 d | 6 d | 14 d | 28 d | |

| Control | 444.9 ± 17.2 | 441.5 ± 14.4 | 444.1 ± 25.4 | 452.6 ± 16.9 | 483.9 ± 24.5 | 527.7 ± 20.2 |

| Acetaminophen | 450.1 ± 17.6 | 441.2 ± 16.0 | 435.5 ± 20.0 | 453.0 ± 21.0 | 498.0 ± 15.9 | 552.9 ± 41.4 |

| Buprenorphine | 454.2 ± 15.8 | 463.1 ± 15.1 | 452.1 ± 10.3 | 444.3 ± 14.3 | 493.8 ± 19.4 | 541.9 ± 26.1 |

| Tramadol–gabapentin | 427.1 ± 10.4 | 432.2 ± 12.4 | 429.0 ± 11.3 | 425.5 ± 10.6 | 452.9 ± 23.6 | 500.9 ± 23.1 |

| Ibuprofen | 430.2 ± 17.7 | 430.2 ± 18.5 | 432.0 ± 18.2 | 435.6 ± 19.1 | 467.1 ± 28.1 | 508.1 ± 28.6 |

Rats were weighed immediately prior to the surgical procedure and before each gait-analysis session.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to quantify and compare the efficacy of different analgesic agents by using an established rat model for supraspinatus tendon healing and a novel gait-analysis system. We demonstrated that temporal, spatial, and force parameters of gait analysis can be used to compare the effectiveness of several common analgesics. The results support our hypothesis that significant differences in rat ambulation indicative of pain would occur between analgesic groups. Gait parameters that were of particular importance were stride length, step length, and vertical force. Our data also support the hypothesis that there would be a difference in tendon-to-bone healing between several common analgesics. Specifically, the ibuprofen group demonstrated significantly decreased stiffness (and therefore poorer healing) at the tendon insertion site.

For this study, we used a control group that received the surgical injury to the left limb and subsequent repair with no analgesics. This group, rather than a completely naïve ‘normal’ group, was necessary for comparison in our study for 2 specific reasons. First, regardless of whether the analgesics given eliminated all pain, the functional mechanical properties of the tendon insertion and joint space have been modified. This manipulation could alter the gait parameters in such a way that they might never return completely to normal, baseline values. The improvement of particular parameters relative to those of our control group, therefore, reflects the analgesic efficacy. Second, without a control group that underwent injury and repair without analgesia, we would have no baseline values to determine whether the level of analgesia provided by the different agents had any effect on gait parameters at all. This consideration is of particular importance for the group that received acetaminophen in their drinking water, given the current debate regarding whether this method provides any significant analgesia at all. In addition, historic data from previous studies using rats of the same ages and weights were available, and we were able to make general comparisons with our current data (discussed following).

Buprenorphine has several distinct characteristics that render it the best choice among the analgesics studied, in terms of prolonged duration of action and effective control of pain.20,52 In our current study, buprenorphine demonstrated the greatest quantifiable improvement of all gait analysis parameters measured. Compared with no analgesia, buprenorphine led to significant differences in stride length, step length, and vertical forces on both days 2 and 4 after surgery. The buprenorphine group was the only one that was significantly different from the control group on day 4. This finding can be interpreted as indicating that only the buprenorphine group achieved a notable level of analgesia at this time point. When buprenorphine treatment was discontinued, there was a shift in gait parameters toward control values on day 6, and this shift was maintained throughout the remainder of the study. In addition, the buprenorphine group was the only group which displayed statistically higher propulsion forces, operative limb speed, and rate of loading compared with the control group. Furthermore, buprenorphine-treated rats displayed gait parameters closest to the historic ‘normative’ uninjured animal data. In particular, the values for stride length, step length, and vertical force on days 2 and 4 after surgery were very similar to historic normative values (data not shown). These findings are indicative of highly effective analgesia. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that buprenorphine may be inducing a hyperactive state.12,18,53 Nevertheless, we believe that, among the agents we tested, buprenorphine provided the most effective analgesia.

The other analgesic that had increased gait-analysis parameters relative to the control group was oral ibuprofen. Similar to the buprenorphine group, ibuprofen-treated rats showed significant increases in stride length, step length, and vertical force on day 2 after surgery. However, despite consistently increased parameters, data from the ibuprofen group—unlike the buprenorphine-treated rats—no longer reached statistical significance on day 4. Ibuprofen likely was still providing some analgesia but was less effective than buprenorphine at this time point. Interestingly, in terms of speed of the operative limb, the ibuprofen group did not differ from any group, suggesting that the level of analgesia it provides is somewhere between those of buprenorphine and the other drugs, which were even lower in analgesic efficacy. When considering the analgesic properties of ibuprofen alone, the data indicate that it is fairly efficacious in relieving early postprocedural pain but may serve better in a multimodal approach to analgesia.

The combination of gabapentin and tramadol may provide some distinct analgesic properties.44 Rats in this group showed a statistically longer step length and tended toward greater propulsion forces and stride length. The combination of these 2 agents does seem to achieve some pain relief after surgery, although to a much lower extent than do buprenorphine and ibuprofen. In a situation in which controlled substances or NSAID cannot be used, gabapentin–tramadol may provide some beneficial pain relief.

Due to the ease of its administration in the drinking water, flavored acetaminophen is an appealing option as a form of postprocedural analgesia. However, the evidence regarding acetaminophen as a viable analgesic in the postprocedural rodent model has been the subject of debate.11,33,45,50,64 To account for the known neophobia of laboratory rats, we provided treated drinking water beginning 48 h prior to the procedure.4,62 When compared with the control group, acetaminophen-treated rats showed no distinct difference in any gait-analysis parameter. In addition, this group was the only experimental group that showed evidence of nonweight-bearing lameness of the operative limb. We strongly believe the data we acquired support the finding that acetaminophen in drinking water is a poor form of postprocedural analgesia. This method may serve some purpose if the model involves minor pain instead of the moderate to high level of pain experienced by rats in the model we used. In addition, the amount of drinking water consumed was not measured, so whether our rats received an adequate dose is unknown. Furthermore, acetaminophen-treated rats had a 3.3% decrease in body weight relative to baseline by day 4. Therefore, rats may have been drinking less and may not have received the desired dose. According to the data we obtained in the current study, we cannot recommend acetaminophen-treated drinking water as a viable form of analgesia.

We noted several different patterns in weight loss and gain among the various groups. Pain and the provision of analgesics can alter the food and water intake of rodents as well as their subsequent weight loss or gain.17,18,37,54,55,62,64 Control rats lost weight on days 2 and 4 after surgery, with a loss of less than 1% on each day. We saw greater losses in the acetaminophen group, which showed losses of 2% on day 2 and 3% on day 4 after surgery. This finding suggests that acetaminophen may have caused the rats to consume less food and water; the other groups maintained or gained weight at the day 2 time point. However, unlike the ibuprofen group, rats given buprenorphine lost weight on days 4 (less than 1%) and 6 (2%) after surgery, and the tramadol–gabapentin group lost weight (less than 1%) on day 6. The weight loss seen in all groups was very small and likely of little concern in terms of animal welfare but may shed light on important behavioral changes that could affect analgesic utility. Long-term use of buprenorphine in rats has been shown to reduce food intake, perhaps explaining their higher weight loss despite the drug's superior analgesic efficacy as determined from our gait analysis.36

We hypothesized that we would find decreases in tendon biomechanical properties (that is, poor healing) with decreases in pain, due to excessive loading at the repair site. Contrary to our expectation, most analgesic groups did not differ from the control group in these properties. This result does not support our original hypothesis, given that we suspected the increased activity and limb use in rats treated with analgesics would cause excessive loading on healing tissues, leading to impaired healing. The findings we obtained suggest that the amount of pain experienced by these rats and their subsequent activity have no effect on healing of the rotator cuff tendon. However, compared with controls, the ibuprofen group had inferior biomechanical tendon properties. The decreased stiffness in the ibuprofen group is indicative of poor healing. These findings are consistent with other findings indicating NSAID may inhibit tissue healing.2,10,14 Therefore, we recommend using caution when choosing an NSAID in models of postsurgical healing, particularly given that buprenorphine out-performed ibuprofen as an analgesic. It should be noted the ibuprofen is a nonspecific cyclooxygenase-receptor inhibitor. Other NSAID that are selective or preferential for cyclooxygenase 2 may have different effects on tissue healing, and additional testing is warranted.

We have shown that a quantitative approach using a gait-analysis system can be applied to determining the efficacies of analgesic agents. Among the analgesics we tested, buprenorphine performed the best, with higher and longer-lasting efficacy and with no negative effect on tendon-to-bone healing. Although ibuprofen was fairly efficacious as an analgesic, we demonstrated that careful consideration should be used when selecting an NSAID in a healing model due to impairment of optimal healing. Part of the refinement of laboratory animal welfare is the introduction of new analgesic agents, and the model system we used may be a useful tool for future investigations.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the Office of the Senior Vice Provost for Research (University of Pennsylvania), through the NIH/NIAMS-supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30AR050950), and through an NIH R-25 award to the University of Pennsylvania (8R25OD010986). We thank Dr F Claire Hankenson (University Laboratory Animal Resources, Department of Pathobiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) for her insightful input regarding the study design and her continued mentorship of Dr Caro. We thank the ULAR husbandry and veterinary technical staff for collaborative oversight and care of our animals.

References

- 1.Abbott FV, Bonder M. 1997. Options for management of acute pain in the rat. Vet Rec. 140:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman RD, Latta LL, Keer R, Renfree K, Hornicek FJ, Banovac K. 1995. Effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on fracture healing: a laboratory study in rats. J Orthop Trauma 9:392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atcha Z, Rourke C, Neo AH, Goh CW, Lim JS, Aw CC, Browne ER, Pemberton DJ. 2010. Alternative method of oral dosing for rats. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 49:335–343 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer DJ, Christenson TJ, Clark KR, Powell SK, Swain RA. 2003. Acetaminophen as a postsurgical analgesic in rats: a practical solution to neophobia. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 42:20–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beason DP, Connizzo BK, Dourte LM, Mauck RL, Soslowsky LJ, Steinberg DR, Bernstein J. 2012. Fiber-aligned polymer scaffolds for rotator cuff repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 21:245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beason DP, Kuntz AF, Hsu JE, Miller KS, Soslowsky LJ. 2012. Development and evaluation of multiple tendon injury models in the mouse. J Biomech 45:1550–1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedi A, Kovacevic D, Fox AJ, Imhauser CW, Stasiak M, Packer J, Brophy RH, Deng XH, Rodeo SA. 2010. Effect of early and delayed mechanical loading on tendon-to-bone healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:2387–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. 1996. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain 64:493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan TJ, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. 2005. Mechanisms of incisional pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America 23:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen DB, Kawamura S, Ehteshami JR, Rodeo SA. 2006. Indomethacin and celecoxib impair rotator cuff tendon-to-bone healing. Am J Sports Med 34:362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper DM, DeLong D, Gillett CS. 1997. Analgesic efficacy of acetaminophen and buprenorphine administered in the drinking water of rats. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 36:58–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowan A, Doxey JC, Harry EJ. 1977. The animal pharmacology of buprenorphine, an oripavine analgesic agent. Br J Pharmacol 60:547–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtin LI, Grakowsky JA, Suarez M, Thompson AC, DiPirro JM, Martin LBE, Kristal MB. 2009. Evaluation of buprenorphine in a postoperative pain model in rats. Comp Med 59:60–71 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimmen S, Nordsletten L, Engebretsen L, Steen H, Madsen JE. 2009. The effect of parecoxib and indometacin on tendon-to-bone healing in a bone tunnel: an experimental study in rats. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Favata M, Beredjiklian PK, Zgonis MH, Beason DP, Crombleholme TM, Jawad AF, Soslowsky LJ. 2006. Regenerative properties of fetal sheep tendon are not adversely affected by transplantation into an adult environment. J Orthop Res 24:2124–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flecknell PA. 1984. The relief of pain in laboratory animals. Lab Anim 18:147–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flecknell PA. 1996. Laboratory animal anaesthesia. London (UK): Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flecknell PA, Liles JH. 1992. Evaluation of locomotor activity and food and water consumption as a method of assessing postoperative pain in rodents. In: Short CE, Van Poznak A, editors. Animal Pain. New York (NY): Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furedi R, Bolcskei K, Szolcsanyi J, Petho G. 2010. Comparison of the peripheral mediator background of heat injury- and plantar incision-induced drop of the noxious heat threshold in the rat. Life Sci 86:244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gades NM, Danneman PJ, Wixson SK, Tolley EA. 2000. The magnitude and duration of the analgesic effect of morphine, butorphanol, and buprenorphine in rats and mice. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 39:8–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerstenfeld LC, Thiede M, Seibert K, Mielke C, Phippard D, Svagr B, Cullinane D, Einhorn TA. 2003. Differential inhibition of fracture healing by nonselective and cyclooxygenase-2-selective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Orthop Res 21:670–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Lake SP, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. 2007. The role of repair tension on tendon-to-bone healing in an animal model of chronic rotator cuff tears. J Biomech 40:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Mehta S, Perry SM, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. 2004. Supraspinatus tendon organizational and mechanical properties in a chronic rotator cuff tear animal model. J Biomech 37:739–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Williams GR, Thomopoulos S, Soslowsky LJ. 2007. Long durations of immobilization in the rat result in enhanced mechanical properties of the healing supraspinatus tendon insertion site. J Biomech Eng 129:400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes KE, Raucci JA, Jr, Gades NM, Toth LA. 2000. An evaluation of analgesic regimens for abdominal surgery in mice. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 39:18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubbell JA, Muir WW. 1996. Evaluation of a survey of the diplomates of the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine on use of analgesic agents in animals used in biomedical research. J Am Vet Med Assoc 209:918–921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishihara A, Bertone AL, Rajala-Schultz PJ. 2005. Association between subjective lameness grade and kinetic gait parameters in horses with experimentally induced forelimb lameness. Am J Vet Res 66:1805–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson WL, Jindrich DL, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. 2012. Quantitative metrics of spinal cord injury recovery in the rat using motion capture, electromyography, and ground reaction force measurement. J Neurosci Methods 206:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamerman P, Koller A, Loram L. 2007. Postoperative administration of the analgesic tramadol, but not the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor parecoxib, abolishes postoperative hyperalgesia in a new model of postoperative pain in rats. Pharmacology 80:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keegan KG, Wilson DA, Smith BK, Wilson DJ. 2000. Changes in kinematic variables observed during pressure-induced forelimb lameness in adult horses trotting on a treadmill. Am J Vet Res 61:612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kehlet H, Holte K. 2001. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth 87:62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolstad AM, Rodriguiz RM, Kim CJ, Hale LP. 2012. Effect of pain management on immunization efficacy in mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 51:448–457 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krapf D, Kaipel M, Majewski M. 2012. Structural and biomechanical characteristics after early mobilization in an Achilles tendon rupture model: operative versus nonoperative treatment. Orthopedics 35:e1383–e1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen JJ, Arnt J. 1985. Reduction in locomotor activity of arthritic rats as parameter for chronic pain: effect of morphine, acetylsalicylic acid, and citalopram. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 57:345–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leach D, Sumner-Smith G, Dagg AI. 1977. Diagnosis of lameness in dogs: a preliminary study. Can Vet J 18:58–63 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liles JH, Flecknell PA. 1992. The effects of buprenorphine, nalbuphine, and butorphanol alone or following halothane anaesthesia on food and water consumption and locomotor movement in rats. Lab Anim 26:180–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liles JH, Flecknell PA. 1992. The use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for the relief of pain in laboratory rodents and rabbits. Lab Anim 26:241–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liles JH, Flecknell PA. 1994. A comparison of the effects of buprenorphine, carprofen, and flunixin following laparotomy in rats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 17:284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindberg MF, Grov EK, Gay CL, Rustoen T, Granheim TI, Amlie E, Lerdal A. 2013. Pain characteristics and self-rated health after elective orthopaedic surgery—a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 22:1242–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindholm TS, Tornkvist H. 1981. Inhibitory effect on bone formation and calcification exerted by the antiinflammatory drug ibuprofen. An experimental study on adult rat with fracture. Scand J Rheumatol 10:38–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu YM, Zhu SM, Wang KR, Feng ZY, Chen QL. 2008. Effect of tramadol on immune responses and nociceptive thresholds in a rat model of incisional pain. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 9:895–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumiya LC, Sorge RE, Sotocinal SG, Tabaka JM, Wieskopf JS, Zaloum A, King OD, Mogil JS. 2012. Using the Mouse Grimace Scale to reevaluate the efficacy of postoperative analgesics in laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 51:42–49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKeon GP, Pacharinsak C, Long CT, Howard AM, Jampachaisri K, Yeomans DC, Felt SA. 2011. Analgesic effects of tramadol, tramadol–gabapentin, and buprenorphine in an incisional model of pain in rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:192–197 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mickley GA, Hoxha Z, Biada JM, Kenmuir CL, Bacik SE. 2006. Acetaminophen self-administered in the drinking water increases the pain threshold of rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 45:48–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newton CD, Nunamaker DM. 1985. Textbook of small animal orthopaedics. Ithaca (NY): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parimi M, Zhao C, Thoreson AR, An KN, Amadio PC. 2012. Does loading velocity affect failure strength after tendon repair? J Biomech 45:2939–2942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peltz CD, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF, Sarver JJ, Kim SY, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. 2009. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91:2421–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. 2009. Alterations in function after rotator cuff tears in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18:296–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Persinger MA. 2003. Rats’ preferences for an analgesic compared to water: an alternative to “killing the rat so it does not suffer.” Percept Mot Skills 96:674–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reuther KE, Thomas SJ, Sarver JJ, Tucker JJ, Lee CS, Gray CF, Glaser DL, Soslowsky LJ. 2013. Effect of return to overuse activity following an isolated supraspinatus tendon tear on adjacent intact tendons and glenoid cartilage in a rat model. J Orthop Res 31:710–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robertson SA, Lascelles BD, Taylor PM, Sear JW. 2005. PK–PD modeling of buprenorphine in cats: intravenous and oral transmucosal administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 28:453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roughan JV, Flecknell PA. 2000. Effects of surgery and analgesic administration on spontaneous behaviour in singly housed rats. Res Vet Sci 69:283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roughan JV, Flecknell PA. 2003. Evaluation of a short-duration behaviour-based postoperative pain scoring system in rats. Eur J Pain 7:397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roughan JV, Flecknell PA. 2004. Behaviour-based assessment of the duration of laparotomy-induced abdominal pain and the analgesic effects of carprofen and buprenorphine in rats. Behav Pharmacol 15:461–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarver JJ, Dishowitz MI, Kim SY, Soslowsky LJ. 2010. Transient decreases in forelimb gait and ground reaction forces following rotator cuff injury and repair in a rat model. J Biomech 43:778–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shah A, Jung D. 1987. Dose-dependent pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos 15:151–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shih AC, Robertson S, Isaza N, Pablo L, Davies W. 2008. Comparison between analgesic effects of buprenorphine, carprofen, and buprenorphine with carprofen for canine ovariohysterectomy. Vet Anaesth Analg 35:69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon AM, O'Connor JP. 2007. Dose- and time-dependent effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition on fracture healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89:500–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, Banerji I, Moalli MR. 1996. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 5:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sotocinal SG, Sorge RE, Zaloum A, Tuttle AH, Martin LJ, Wieskopf JS, Mapplebeck JC, Wei P, Zhan S, Zhang S, McDougall JJ, King OD, Mogil JS. 2011. The Rat Grimace Scale: a partially automated method for quantifying pain in the laboratory rat via facial expressions. Mol Pain 7:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Speth RC, Smith MS, Brogan RS. 2001. Regarding the inadvisability of administering postoperative analgesics in the drinking water of rats (Rattus norvegicus). Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 40:15–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spofford CM, Ashmawi H, Subieta A, Buevich F, Moses A, Baker M, Brennan TJ. 2009. Ketoprofen produces modality-specific inhibition of pain behaviors in rats after plantar incision. Anesth Analg 109:1992–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.St A Stewart L, Martin WJ. 2003. Evaluation of postoperative analgesia in a rat model of incisional pain. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 42:28–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. 1999. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 8:296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomopoulos S, Hattersley G, Rosen V, Mertens M, Galatz L, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. 2002. The localized expression of extracellular matrix components in healing tendon insertion sites: an in situ hybridization study. J Orthop Res 20:454–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Todorovic SM, Rastogi AJ, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. 2003. Potent analgesic effects of anticonvulsants on peripheral thermal nociception in rats. Br J Pharmacol 140:255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yanarates O, Dogrul A, Yildirim V, Sahin A, Sizlan A, Seyrek M, Akgul O, Kozak O, Kurt E, Aypar U. 2010. Spinal 5-HT7 receptors play an important role in the antinociceptive and antihyperalgesic effects of tramadol and its metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, via activation of descending serotonergic pathways. Anesthesiology 112:696–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao C, Moran SL, Cha SS, Kai Nan A, Amadio PC. 2007. An analysis of factors associated with failure of tendon repair in the canine model. J Hand Surg Am 32:518–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]