Abstract

Infection with Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium sequence type (ST) 313 is associated with high rates of drug resistance, bloodstream infections, and death. To determine whether ST313 is dominant in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we studied 180 isolates collected during 2007–2011; 96% belonged to CRISPOL type CT28, which is associated with ST313.

Keywords: Salmonella Typhimurium, ST313, CRISPOL, MLST, Central Africa, bacteremia, bacteria, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium multilocus sequence type (ST) 313 has been reported as an emerging cause of invasive salmonellosis in sub-Saharan Africa (1). ST313 is almost exclusively from sub-Saharan Africa, is characterized by a degraded genome capacity similar to that of S. enterica Typhi, has high rates of antimicrobial drug resistance, and is associated with bloodstream infections and mortality rates >25% (2). Whole-genome sequence analysis of 129 ST313 strains, isolated during 1988–2010 from 7 countries of sub-Saharan Africa, identified 2 dominant genetic lineages, I and II. These lineages emerged ≈52 and ≈32 years ago, respectively, possibly coevolving with the spread of HIV (3). Although lineage I has not been observed since the mid-2000s, lineage II has been observed with increasing frequency. However, data from Central Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are scarce, and information is limited to 10 genomes from strains isolated >20 years ago (3). To determine whether ST313 is the dominant ST among invasive S. enterica Typhimurium in the DRC, we studied 180 isolates collected during 2007–2011.

The Study

We earlier described a series of invasive non-Typhi S. enterica isolates from blood cultures collected in 7 of the 11 provinces in the DRC during 2007–2011 (Figure 1) (4). In that study, a health care facility–based survey was administered to persons who met the eligibility criteria of suspected bacteremia at time of presentation and patient age >2 months. Blood culture vials were shipped to Kinshasa and processed according to standard identification procedures (4). A total of 233 non-Typhi S. enterica isolates were recovered, 184 (79%) of which belonged to serotype Typhimurium (4). The serotypes for all S. enterica Typhimurium isolates were determined locally and later confirmed at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. Most (180/184, 98.7%) S. enterica Typhimurium isolates were subsequently shipped to the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France, for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Provinces with sample collection sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2007–2011(4).

The population structure of these 180 S. enterica Typhimurium isolates was assessed by CRISPOL typing. CRISPOL is a recently developed high-throughput assay based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) polymorphisms (5). This bead-based hybridization assay is designed to detect the presence or absence of 72 short variable DNA sequences (spacers) from both CRISPR loci of S. enterica Typhimurium. Initially, 245 different CRISPOL types (CTs) were identified in a 2012 study that included 2,200 isolates (5); just before we conducted the study reported here, the CRISPOL Salmonella Typhimurium database of the Pasteur Institute contained >7,000 strains comprising >750 different CTs.

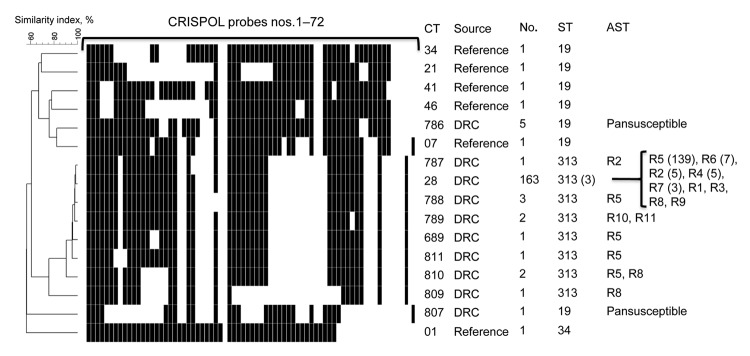

A total of 174 (96.7%) S. enterica Typhimurium isolates from the DRC belonged to the CT28 group, of which 163 (90.5%) were CT28. A total of 11 (6.1%) isolates belonged to 7 other CTs that were single-spacer variants (loss of a single spacer), single-event variants (loss of >2 contiguous spacers), or double-event variants of CT28 (Figure 2). Six (3.3%) isolates belonged to 2 CTs not related to CT28. CT28 had been associated with ST313 in a multidrug-resistant DT56 S. enterica Typhimurium isolate from Senegal and in the D23580 ST313 lineage II genome (5). In contrast, the analysis of raw pyrosequence data for genome A130 (3), representative of ST313 lineage I, corresponded to CT698, distinct from the CT28 group.

Figure 2.

Representative CRISPOL profiles of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates studied. CRISPOL is a recently developed high-throughput assay based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) polymorphisms. Black squares indicate presence of the CRISPR spacer, detected by the corresponding probe; white squares indicates absence of the spacer. The dendrogram was generated by using BioNumerics version 6.6 software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) as described (5). The CRISPOL types (CTs) detected among the 180 isolates from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are labeled as DRC in the Source column. Six common CTs of the Pasteur Institute CRISPOL database (labeled as reference) are also shown. These CTs are from strains of serotype Typhimurium 02–1800 (CT34, DT120), 02–5270 (CT21, DT104), LT2 (CT41, DT4), 02–2561 (CT46, DT12), 02–1749 (CT7, DT14) or its monophasic variant of antigenic formula 1,4,[5],12:i:-, 07–1777 (CT1, DT193). For each distinct CT, the numbers of corresponding isolates, their sequence types (STs), and their antimicrobial drug susceptibility testing (AST) data are indicated. For the ST and AST columns, the numbers in parentheses refer to the number (>2) of tested isolates with such result. AST data are shown only for DRC isolates. The resistance types were as follows: R1, ASKTNGSulTmpC; R2, ASKTNGSulTmpCTe; R3, AC; R4, ASSulTmp; R5, ASSulTmpC; R6, ASSulTmpCNal; R7, ASSulTmpCTe; R8, ASulTmpC; R9, SSulTmpC; R10, ACroCazSKTNGSulTmpCTeAzi; and R11, ACroSKTNGSulTmpCTeNaAzi. Abbreviations used in the descriptions of resistance types are as follows: A, amoxicillin; Cro, ceftriaxone; Caz; ceftazidime; S, streptomycin; K, kanamycin; T, tobramycin; N, netilmicin; G, gentamicin; Sul, sulfamethoxazole; Tmp, trimethoprim; C, chloramphenicol; Te, tetracycline; Nal, nalidixic acid; Azi, azithromycin.

To confirm the association of ST313 to the CT28 group, we performed multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (6) on 12 isolates. A total of 3 isolates belonged to CT28, and 1 isolate of each single-spacer, single-event, and double-event variant was tested, resulting in 10 isolates from the CT28 group. We also performed MLST on 1 isolate of each of the 2 non–CT28 group isolates. All 10 CT28 group isolates tested were ST313; both non–CT28 group isolates tested were ST19.

Antimicrobial drug susceptibility has been studied with a limited panel of 7 drugs (4). We performed additional susceptibility testing by disk diffusion with a panel of 32 antimicrobial agents (Bio-Rad, Marnes-La-Coquette, France) (7). Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) phenotype was assessed by using the double-disk synergy method (8). For all ESBL-producing isolates, MICs of ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, azithromycin, and imipenem were determined by the Etest macromethod (bioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France). Results were interpreted according to break points defined by the Antibiogram Committee of the French Society for Microbiology (www.sfm-microbiologie.org/). Susceptible strains were defined as having a ceftriaxone MIC <1 mg/L, ceftazidime MIC <4 mg/L, azithromycin MIC <16 mg/L, and imipenem MIC <2 mg/L. Resistance was defined as having a ceftriaxone MIC >2 mg/L, ceftazidime MIC >4 mg/L, azithromycin MIC >16 mg/L, and imipenem MIC >8 mg/L. The presence of macrolide resistance genes was assessed by PCR and sequencing as described elsewhere (7). Of the 174 CT28 group isolates, 167 (96%) were resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in combination with other drugs (Figure 2); the remaining isolates were resistant to 1 or 2 of these drugs. Two isolates were resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ceftriaxone MIC 6–32 mg/L, ceftazidime MIC 4–32 mg/L); both contain the ESBL blaSHV-2a gene (4). We report that both isolates contain the mph(A) gene encoding a macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase that inactivates macrolides (azithromycin MIC 96–128 mg/L). All 6 non-CT28 group isolates were susceptible to all drugs tested (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Our data are based on the analysis of S. enterica Typhimurium isolates recovered from >9,600 blood cultures collected during a 4-year period from distinct parts of the DRC. We found that >96% of the S. enterica Typhimurium isolates belonged to the CT28 group. Because of the strong association between CT28 group and ST313, our findings suggest high rates of ST313 among invasive salmonellosis in the DRC.

Of the 10 genomes from the DRC isolated during 1988–1992 (3), genetic lineages I and II were identified at approximately equal rates. Of the more recent isolates (2007–2011) described here, all ST313 isolates belonged to the CT28 group, associated with lineage II. A notable feature of lineage II is chloramphenicol resistance resulting from a cat gene within a specific Tn21-like element, carried by the virulence-associated plasmid pSLT (3). In the set described herein, we observed chloramphenicol resistance in >97% of all isolates belonging to the CT28 group. The almost complete replacement of lineage I isolates by lineage II isolates from Kenya and Malawi has also been reported (1,9).

Our data are based on invasive S. enterica Typhimurium isolates collected in a nonsystematic health care facility–based approach and do not include noninvasive strains of S. enterica Typhimurium. Wain et al. (10) recently cited unpublished data showing that ST313 S. enterica Typhimurium might be a common cause of gastroenteritis among immune-competent patients. A human reservoir for multidrug-resistant S. enterica Typhimurium and Enteritidis in Kenya has been suggested because of the presence of similar strains in asymptomatic siblings and parents of index case-patients (carriage prevalence 6.9%) (11). Whole-genome sequencing of ST313 strains has shown genome degradation, including pseudogene formation and chromosomal deletions as have been observed for human-restricted S. enterica Typhi (12,13), suggesting that ST313 might be undergoing an evolution toward niche specialization or, more likely, human adaptation (1).

Our results indicate very high rates of multidrug-resistant S. enterica Typhimurium ST313 among invasive non-Typhi Salmonella infections in the DRC. Future field studies involving patients with uncomplicated Salmonella spp. infections will help determine whether ST313 S. enterica Typhimurium in Central Africa is an opportunist or a primary pathogen. Systematic analyses of potential nonhuman and human reservoirs of S. enterica Typhimurium might provide a better understanding of the transmission dynamics of this emerging pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylvie Issenhuth-Jeanjean, Laëtitia Fabre, Lucile Sontag, and Nicolas Alexandre for technical assistance with CRISPOL typing, CRISPR sequencing, MLST, and determination of mechanisms of resistance to antimicrobial drugs. We also thank all staff and participants who supported the sample collection in the DRC.

Biography

Dr Ley is a medical biologist, epidemiologist, and researcher at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. His research interests include infectious diseases in tropical countries.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ley B, Le Hello S, Lunguya O, Lejon V, Muyembe JJ, Weill FX, et al. Invasive Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium infections, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2007–2011. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Apr [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2004.131488

References

- 1.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19:2279–87. 10.1101/gr.091017.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet. 2012;379:2489–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, Harris SR, Parry CM, Al-Mashhadani MN, et al. Intra-continental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1215–21. 10.1038/ng.2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunguya O, Lejon V, Phoba MF, Bertrand S, Vanhoof R, Glupczynski Y, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in invasive non-typhoid Salmonella from the Democratic Republic of the Congo: emergence of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility and extended-spectrum beta lactamases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2103. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabre L, Zhang J, Guigon G, Le Hello S, Guibert V, Accou-Demartin M, et al. CRISPR typing and subtyping for improved laboratory surveillance of Salmonella infections. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36995. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achtman M, Wain J, Weill FX, Nair S, Zhou Z, Sangal V, et al. Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002776 . 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Hello S, Harrois D, Bouchrif B, Sontag L, Elhani D, Guibert V, et al. Highly drug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Kentucky ST198–X1: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:672–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70124-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarlier V, Nicolas MH, Fournier G, Philippon A. Extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:867–78. 10.1093/clinids/10.4.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Msefula CL, Kingsley RA, Gordon MA, Molyneux E, Molyneux ME, MacLennan CA, et al. Genotypic homogeneity of multidrug resistant S. Typhimurium infecting distinct adult and childhood susceptibility groups in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42085. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wain J, Keddy KH, Hendriksen RS, Rubino S. Using next generation sequencing to tackle non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:1–5 . 10.3855/jidc.3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kariuki N, Kiiru J, Mwituria J, Muyodi J, et al. Invasive multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Africa: zoonotic or anthroponotic transmission? J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:585–91 . 10.1099/jmm.0.46375-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkhill J, Dougan G, James KD, Thomson NR, Pickard D, Wain J, et al. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature. 2001;413:848–52. 10.1038/35101607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt KE, Parkhill J, Mazzoni CJ, Roumagnac P, Weill FX, Goodhead I, et al. High-throughput sequencing provides insights into genome variation and evolution in Salmonella Typhi. Nat Genet. 2008;40:987–93. 10.1038/ng.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]