SUMMARY

Twenty years of sky-high tuberculosis (TB) incidence rates and high TB mortality in high human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence countries have so far not been matched by the same magnitude or breadth of responses as seen in malaria or HIV programmes. Instead, recommendations have been narrowly focused on people presenting to health facilities for investigation of TB symptoms, or for HIV testing and care. However, despite the recent major investment and scale-up of TB and HIV services, undiagnosed TB remains highly prevalent at community level, implying that diagnosis of TB remains slow and incomplete. This maintains high transmission rates and exposes people living with HIV to high rates of morbidity and mortality.

More intensive use of TB screening, with broader definitions of target populations, expanded indications for screening both inside and outside of health facilities, and appropriate selection of new diagnostic tools, offers the prospect of rapidly improving population-level control of TB. Diagnostic accuracy of suitable (high throughput) algorithms remains the major barrier to realising this goal.

In the present study, we review the evidence available to guide expanded TB screening in HIV-prevalent settings, ideally through combined TB-HIV interventions that provide screening for both TB and HIV, and maximise entry to HIV and TB care and prevention. Ideally, we would systematically test, treat and prevent TB and HIV comprehensively, offering both TB and HIV screening to all health facility attendees, TB households and all adults in the highest risk communities. However, we are still held back by inadequate diagnostics, financing and paucity of population-impact data. Relevant contemporary research showing the high need for potential gains, and pitfalls from expanded and intensified TB screening in high HIV prevalence settings are discussed in this review.

Keywords: tuberculosis, screening, case finding, HIV, disease control, community, health facility, prevention

In high human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence settings, population-level tuberculosis (TB) incidence increased in parallel with adult HIV prevalence in the 1990s and remains extremely high, with over 1% of adults diagnosed with TB each year in many Southern African towns.1 Outbreaks of multi- and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) have been generated in HIV care clinics, and then spread into general communities.2,3 Autopsy studies show that TB is the single biggest killer of people living with HIV (PLHIV), being the cause in 32% to 45% of HIV-related deaths4 and with a high proportion of fatal cases undiagnosed in life.4,5 Of the estimated 430 000 TB-related deaths among PLHIV during 2011, 79% were in Africa. These stark facts demonstrate the urgent need to strengthen TB prevention and care services using all available approaches, including more ambitious TB screening strategies.

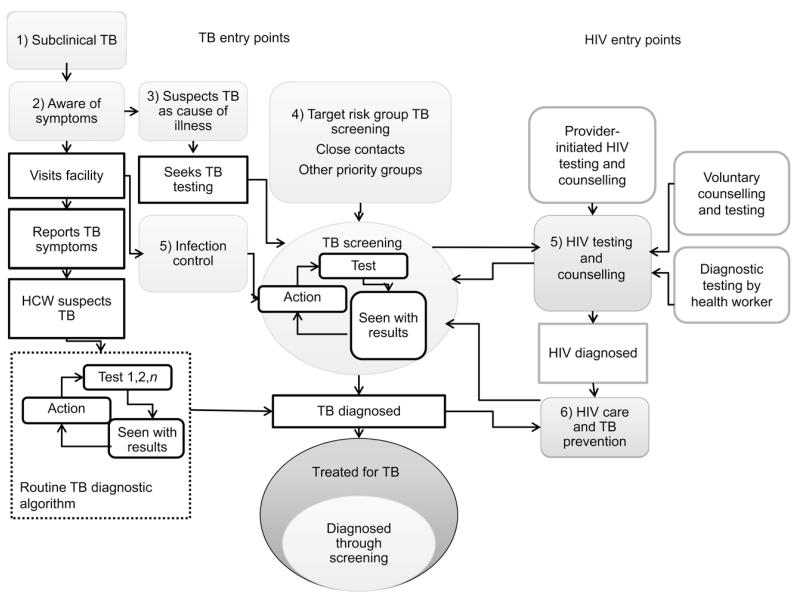

TB screening is the first step in both anti-tuberculosis treatment and TB prevention pathways, and has an integral place in routine HIV care and infection control. Key potential entry points for TB screening are illustrated in Figure 1. TB screening can be conducted at the clinic, facility or community level (Table 1),6–12 and can be initiated by TB programmes, infection control services in general facilities or HIV testing and care services. Developing and scaling up effective TB screening strategies will ideally follow the same kind of combined approach that has proved effective for HIV testing and counselling (HTC). Diagnostic testing, provider-initiated HTC and promotion of client-initiated testing through ‘know your status’ campaigns in facility- and community-based testing services have led to remarkable progress in universal access to HIV testing and care, with both HIV and TB incidence rates falling regionally.13 Early HIV detection and antiretroviral therapy (ART) are increasingly being recognised as critical for HIV prevention. Recommendations in the United States are moving towards annual HIV screening for all adults, while in Africa increasing emphasis is placed on home-based testing, due to much higher acceptability and uptake than other modalities.14

Figure 1.

Patient flow and main entry points into TB screening. HIV entry points (5 and 6) are considered separately from other targeted risk groups, such as household contacts (4). TB screening can be directed against subclinical TB or at early stages of health seeking. TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HCW = health care worker.

Table 1.

Broad strategies and representative examples of different approaches to providing TB screening with integrated HIV testing and care

| Strategy | TB-HIV integration | Evidence of population-level impact on epidemiology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Household TB contact tracing | Visit and screen in households or invitation for facility-based screening | Provide early TB detection and TB preventive therapy following close contact Combine with HTC; ideally include home-based initiation of TB and HIV care |

ZAMSTAR Reduced prevalence of TB from combined TB and HIV intervention (Ayles)6 Requires rapid response |

| 2 Screening and testing for TB in the general community | Outreach mobile services Door-to-door visits Community health worker visits:

|

Increase completeness of case detection and reduced delay in TB diagnosis Provide HIV testing: to all diagnosed with TB, with symptoms of TB, or as fully integrated TB-HIV screening Ideally include home-based initiation of TB and HIV care and prevention |

DETECTB (increased case notifications and reduced undiagnosed TB; Corbett)7 Reduced mortality from increased frequency of X-ray screening (Churchyard)8 |

| 3 Testing for HIV in the community, combined with TB screening | As for TB screening above | Provide TB screening during HTC Ideally initiate HIV and TB care and prevention | Home-based HIV testing reaches high coverage Few examples of fully integrated HIV and TB testing, and none assessed from TB control perspective |

| 4 Facilitating access to TB diagnostic services | Sputum collection point Preparation and transportation of slides by CHWs |

Avoid need to visit health facility for initial TB diagnosis | One important negative result (Ayles)6 ZAMSTAR: increased case notifications in remote areas with poor access to health facilities |

| 5 Raising awareness and community mobilisation | Advertising and media campaigns Engagement through existing community-based organisations | Reduce patient delays in health seeking Increase demand for services |

One important negative result (Ayles)6 |

| 6 Facility-based screening for HIV and TB | Provider-initiated screening at every patient visit | Existing policy but poorly implemented | O’Grady showed 23% of unselected adult facility attendees had culture-positive TB9 |

| 7 Strengthen general facility-based services | Courteous services Efficient routine TB-HIV services Use of sensitive TB diagnostics High linkage and retention in care Infection control |

Existing policy but poorly implemented | Churchyard showed no population impact from community-wide isoniazid without HTC despite individual benefit10 |

| 8 Strengthen HIV care services | Increase coverage of ART Early detection of HIV and treatment Increased use of isoniazid preventive therapy |

Highly successful scale-up of HIV care services across Africa coinciding with declining TB incidence rates | Strong evidence of impact on individual, community and regional TB incidence from ART scale-up (Suthar)11 Middelkoop showed evidence of community effect on undiagnosed TB12 |

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HTC = HIV testing and counseling; ZAMSTAR = Zambia South Africa TB and HIV Reduction; CHW = community health worker; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

These ambitious targets and achievements contrast with a more conservative approach to TB screening. Although TB, like HIV, has characteristically prolonged infectiousness before diagnosis that plays a critical role in maintaining transmission in the community, there is no TB equivalent of the rapid diagnostic tests for HIV that provides highly sensitive and specific results within 20 minutes and cost less than US$1. New diagnostics for TB, increasing levels of political commitment to reducing HIV-related TB morbidity and mortality, and the optimism arising from the success of ART scale-up has heightened interest in TB screening, including ‘active’ and ‘intensified’ case-finding approaches in communities.

SCREENING FOR TB AS PART OF THE RESPONSE TO TB-HIV IN HIGH HIV PREVALENCE SETTINGS

International policy

International policy is supporting more intensive use of TB screening, with updated recommendations for screening in PLHIV and close contacts of TB patients published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 and guidance encouraging broader consideration of screening in other priority groups, as well as operational research priorities.15–17 More definitive TB screening guidelines will be published in 2013 following systematic reviews that have highlighted major evidence gaps but which also stress the need for caution.

Rationale and general principles

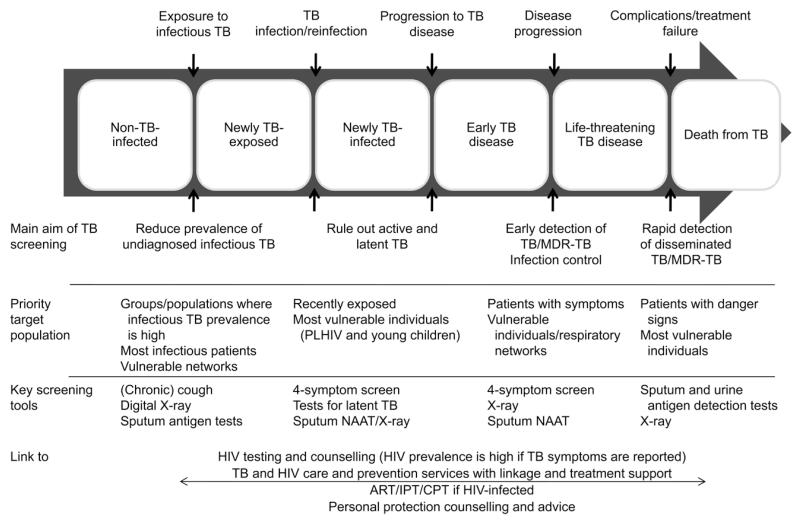

The main aims of TB screening are 1) to reduce individual morbidity and mortality through early diagnosis and treatment, 2) to reduce TB transmission by shortening the infectious period (Figure 2) and 3) to exclude TB to allow preventive treatment (such as isoniazid) to be started. In PLHIV, screening also reduces the risk of severe ‘unmasking’ of inflammatory reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) when starting ART,17,18 and may reduce early mortality in the critical ill. TB screening serves to raise awareness of TB symptoms and can have an important ‘indirect’ effect on subsequent health seeking, reducing subsequent patient delays in health seeking as well as providing direct access to diagnosis. This is especially pronounced in community-based interventions, and may have been a major contributor to the success of two recent interventions that reduced undiagnosed infectious TB at the population level.6,7 Finally, TB screening has clear opportunities for linkage with HIV testing and care services, as discussed below.

Figure 2.

TB progression along an individual patient pathway. Depending on the nature of TB screening, individuals can be targeted at any point along their disease progression. This will influence the choice of diagnostic tools and the principal aim of screening. TB = tuberculosis; MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant TB; PLHIV = people living with HIV; NAAT = nucleic acid amplification test; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy; IPT = isoniazid preventive therapy; CPT = cotrimoxazole preventive therapy.

Epidemiology of undiagnosed tuberculosis disease

The target of TB screening is undiagnosed infectious TB, which is still highly prevalent, as summarised in Table 2.7,9,10,12,19–31 Variation between countries is marked and predates the HIV epidemic.1,32,33 Lengthy delays in diagnosis and missed diagnosis are still reported by many HIV-positive and HIV-negative TB patients, despite major investment in strengthening health systems and TB services during the last decade.17,18,34,35

Table 2.

Prevalence of undiagnosed culture-positive TB in facility- and community-level studies from high HIV prevalence settings

| Pre/post intervention |

Culture+ TB % |

HIV prevalence % positive* |

Infectious TB in HIV− participants* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year, reference | Country | Setting | Population | Culture method | Participants n |

Culture+ n |

Smear+ % |

Culture+ % |

|||

| General population | |||||||||||

| Den Boon, 200619 | South Africa | Urban | General | NA | LJ | 2608 | 26 | 1.0 | ND | ND | ND |

| Wood, 200720† | South Africa | Urban | General | Pre | MGIT | 762 | 12 | 1.6 | 22.8 | 16.7 | 25.0 |

| Middelkoop, 201012† | South Africa | Urban | General | Post | MGIT | 1259 | 8 | 0.6 | 25.0 | NS | 50.0 |

| Corbett, 200921‡ | Zimbabwe | Urban | General | Pre | LJ | 10092 | 66 | 0.7 | 21.1 | 51.3 | 46.00 |

| Corbett, 20107‡ | Zimbabwe | Urban | General | Post | LJ | 11018 | 46 | 0.4 | 18.7 | 39.1 | 35.1 |

| Ayles, 200922 | Zimbabwe | Urban + rural | General | NA | MGIT | 8044 | 79 | 1.0 | 28.8 | 59.10 | 45.6 |

| van’t Hoog, 201123 | Kenya | Rural | General | NA | L J+MGIT | 20710 | 123 | 0.6 | 16.8 | NS | NS |

| Shapiro, 201224§ | South Africa | Urban | General | NA | MGIT | 983 | 4 | 0.4 | 20.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Special populations | |||||||||||

| Corbett, 200425 | South Africa | Mines | Miners | NA | LJ | 1773 | 45 | 2.6 | 26.1 | 77.8 | 62.2 |

| Corbett, 200726¶ | Zimbabwe | Urban | Workplace | Post | LJ | 4668 | 15 | 0.3 | 22.0 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Churchyard, 201210# | South Africa | Mines | Miners | Post | MGIT | 12606 | 285 | 2.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| Shapiro, 201224 | South Africa | Urban | TB household | NA | MGIT | 2166 | 169 | 7.8 | 21.0 | NS | NS |

| Facility-based | |||||||||||

| O’Grady, 20129 | Zambia | Urban | Medical admissions | NA | MGIT | 881 | 201 | 22.8 | 65 | NS | 16.2 |

| Hoffman, 201327 | South Africa | 17 urban clinics | Antenatal clinic HIV+ | NA | MGIT | 1403 | 35 | 2.5 | 100 | NA | NA |

| HIV care clinics | |||||||||||

| Shah, 200928 | Ethiopia | Urban | Voluntary counselling and testing clinic | NA | LJ | 427 | 27 | 6.3 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Lawn, 200929 | South Africa | Urban | ART clinic | NA | MGIT | 235 | 58 | 25.7 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Cain, 201030 | South East Asia | Urban | HIV clinic | NA | LJ+MGIT | 1724 | 267 | 15.5 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Bassett, 201031 | South Africa | Urban | HIV clinic | NA | MGIT | 825 | 157 | 19.0 | 100 | NA | NA |

HIV prevalence refers to % positive in those consenting to be tested. ND = HIV testing not done as part of prevalence survey.

Repeated prevalence surveys in the same South African township before and after scale-up of facility-based HIV testing and care services, including ART clinic and TB screening as part of infection control and HIV care.

Before-and-after prevalence surveys in population provided with six rounds of periodic TB screening in the community.

Surveys for undiagnosed TB in household contacts and controls from the same South African community.

Prevalence surveys following 2 years of promoting HIV testing and provision of easy access to culture-based TB diagnosis and radiological diagnosis of patients with suspected smear-negative TB through workplace-based primary care clinics.

Survey for undiagnosed TB in goldminers following a randomised trial of community-wide isoniazid preventive therapy. Results include both arms.

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; + = positive; − = negative; NA = not applicable; L J = Löwenstein-Jensen; ND = not done; MGIT = Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube; NS = not stated.

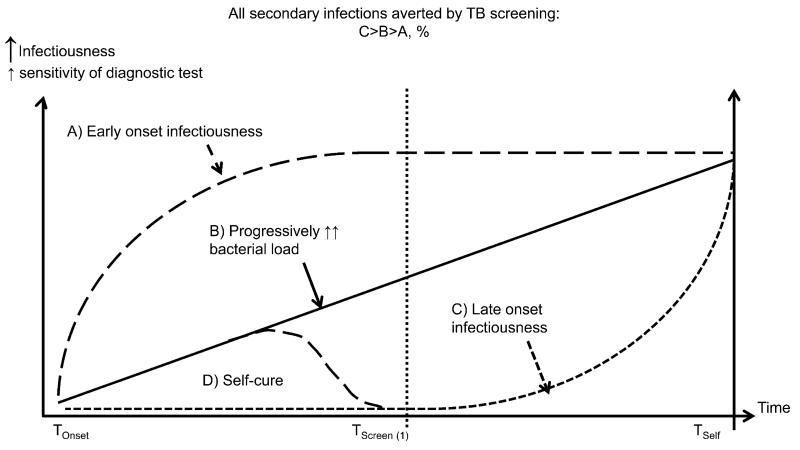

Patient delays in seeking care can also be prolonged, particularly among HIV-negative TB patients, for whom recent estimates suggest a mean duration of smear positivity before diagnosis of >1 year in Africa and even longer in many parts of Asia. In contrast, HIV-related TB progresses more rapidly, with a relatively brief duration of infectiousness (mean of a few weeks to months).20,25,26 A substantial percentage of the total burden of undiagnosed smear-positive TB in the general community, the main driver of TB transmission, is thus HIV-negative individuals, even in very high HIV prevalence settings (Table 2 and Figure 336). HIV-related TB, however, dominates the epidemiology of undiagnosed disease in facilities (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Possible patterns of disease progression and onset of infectiousness. TB screening gains in terms of secondary infections averted and ease of diagnosis (sensitivity of diagnostic tools) will depend on the pattern of onset of infectiousness relative to symptoms, and how the screen is targeted. Screening may detect patients who are in the process of self cure following transient culture positivity. Adapted from Dowdy et al.36 TB = tuberculosis.

Undiagnosed infectious TB in HIV-negative individuals is an important control target because of its disproportionate contribution to community transmission, and also due to the high responsiveness to interventions. For example, in Zimbabwe, the prevalence of culture-positive TB fell by 61% in HIV-negative individuals but only 25% in HIV-positive individuals (overall decline 41%) during a 2.5 year intervention based on 6-monthly periodic TB screening in the community targeting individuals with chronic cough and using smear microscopy for diagnosis.7 By the end of the intervention, most undiagnosed infectious TB was HIV-related (Table 2: study 5), illustrating the need for combined approaches to prevent prolonged transmission from HIV-negative patients and reducing the high incidence of new TB disease among PLWHA.7

Whom to target?

Subgroups in whom undiagnosed TB prevalence is consistently ≥1% (number needed to screen [NNTS] of <100 to detect one case of TB if using perfect screening tools), and people being considered for isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) are the natural focus of screening efforts.16 These include patients attending HTC clinics or HIV care clinics,18,37–39 un-selected medical admissions and out-patient attendees,9,38 household contacts of TB patients,21,40 prisoners,38 silica-exposed mineworkers,10 unselected adults in some communities,12,19,21–23,26 and adult residents volunteering symptoms of TB during surveys or outreach TB screening. Prevalence in adults in the general community and other risk groups, including diabetics, is highly variable and needs local situational analysis to guide planning.7,34,41–43

Household contacts, PLHIV and facility attendees stand out as having much higher prevalence rates than other risk groups (Table 2 and 38), indicating an urgent need for effective TB screening using accurate diagnostic tools to provide individual benefit. However, undiagnosed TB in these subgroups is more of a symptom than the main contributor to TB transmission in communities.35,44

OPTIMAL SCREENING STRATEGIES FOR DIFFERENT PRIORITY GROUPS

TB screening has a number of different goals and entry points (Figures 1 and 2) affecting where, how and how often screening should be carried out. For instance, prevention of mortality is the overriding goal when screening acutely ill in-patients, and ideally requires diagnostics able to rapidly detect disseminated HIV-related TB (Figure 2). At the other extreme, interventions aimed at reducing transmission in the general community need to detect infectious participants affordably and efficiently (Figure 2). Critical decisions include which algorithm to use, and whether or not to screen for subclinical TB. Following the general principals of screening, sensitive screening tests should be confirmed by a highly specific test.45 As no current TB screening algorithm is ideal, compromises have to be made.46,47 In practice, TB screening usually starts with either symptoms or X-ray,48 although there is increasing use of Xpert® MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) as both initial and confirmatory test.9,49–51

The performance of all tests tends to be less good due to lower sensitivity when used for screening than for patient-initiated diagnostic testing, as the spectrum of undiagnosed disease detected is shifted towards earlier, paucibacillary cases (Figures 2 and 3): this includes culture, smear microscopy and Xpert.30,41,49,50,52–54 There is considerable incremental yield from combining different tests, or repeating the same test on different specimens.30,53,55 All tests also have relatively low positive predictive value when used for screening, due to the lower prevalence of true disease.

Symptom screening

TB symptoms are the most common first step in TB screening, and may currently be the only feasible option in many settings. However, undiagnosed TB can occur without any reported TB symptoms and, irrespective of HIV status, less than half of culture-positive participants have the ‘hallmark’ symptom of prolonged cough.18 In a meta-analysis of data from 8148 PLHIV screened using culture, prolonged cough was reported by 1530 (20.0%) participants and identified 260 (52.5%) culture-positive participants, while one or more of the four symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats or weight loss) was reported by 3563 (46.6%) participants, including 418 (84.4%) with confirmed TB.18

Subclinical tuberculosis

Subclinical TB (culture-positive TB with none of the above four symptoms) is consistently identified whenever screening is carried out. In very high transmission settings, including household contacts and newly diagnosed patients attending HIV care clinics, numbers of patients with subclinical culture-positive disease can exceed symptomatic cases, and reach very high rates (up to 15%).18,31,50,56 However, the consequences of missing subclinical TB disease need to be weighed against the expense and consequences of more systematic screening of all suspects. For example, adding extra steps in an already tortuous patient pathway could increase loss to care.

Individual consequences of missing subclinical active TB include IRIS, which is rarely fatal, although extremely unpleasant and disruptive to HIV care.57,58 Inappropriate isoniazid monotherapy may even be lifesaving in HIV-positive patients with difficult-to-diagnose TB,59 and there is no clear evidence of increasing drug resistance.60,61 The extent to which subclinical TB contributes to overall TB transmission is unclear,36 and will depend on how infectiousness relates to symptoms (Figure 3). Local TB epidemiology can be dominated by stable, minimally symptomatic but highly infectious ‘super-spreaders’,62 but this does not appear to be a common phenotype,26 and pronounced reductions in undiagnosed TB at the population level can be achieved without systematic screening for subclinical TB.7,11,12

Radiological screening

Chest radiography (CXR) provides the opportunity for high-volume TB screening, and is increasingly feasible due to digital technology. Computer-aided diagnostics,63 validated reading and scoring systems,64 remote reading and lay readers65,66 are all under active investigation. CXR is already part of the adult and paediatric TB diagnostic algorithms, and combines high sensitivity with reasonably high specificity.65,67,68 Immediate decisions on the need for confirmatory testing and follow-up can be made by trained readers,64,66 as exemplified by outreach interventions among hard-to-reach risk groups in Europe.65,69 HIV immunosuppression affects radiological manifestations of TB; low sensitivity has been reported in clinic-based screening,30,70 but not in community-based studies.48 Two studies from Botswana reported a low-to-modest yield and high incremental cost of adding CXR to clinic-based symptom screening.71–73 The main barriers to use are the high capital costs, radiation hazard and lack of skill base in Africa.

New tuberculosis diagnostics for tuberculosis screening

Xpert and urinary lipoarabamannan (LAM) antigen detection are both new diagnostics being used for TB screening, mainly in the context of HIV care. The development and roll-out of the Xpert platform is a major breakthrough for the diagnosis and management of HIV-related TB and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) that was endorsed by the WHO in 2010.74 It has increased sensitivity compared to smear microscopy, and has led to a clinically important decrease in time to diagnosis and treatment initiation in self-presenting patients with suspected TB. The sensitivity of Xpert compared to culture is highest in hospital in-patients with TB symptoms (82–91%).75

Data on the use of Xpert as a TB screening tool in high HIV prevalence populations are currently limited to four studies (Table 3);9,49–51 however, these numbers are likely to increase rapidly. Excluding one very small study of five culture-positive cases, the sensitivity of Xpert compared to culture was lower when used for diagnostic testing (range 58.3–88.2%), but much more sensitive than smear microscopy (sensitivity range 17.6–52.8%). Use of Xpert for routine diagnostic testing is likely to be cost-effective in many settings;76,77 however, affordability, limited throughput capacity and substantially lower sensitivity than culture and CXR may restrict the widespread adoption of this test for screening to specified high TB prevalence groups, such as PLHIV, facility attendees and close contacts, and to confirmatory testing after CXR or symptom screen. More research is needed to define sensitivity, specificity and feasibility in these groups.

Table 3.

Use of Xpert® MTB/RIF for screening

| HIV prevalence |

Culture-positive n |

Sensitivity of smear microscopy % (95%CI) |

Sensitivity of Xpert® MTB/RIF % (95%CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Screening population | % positive | n | |||

| Lawn, 201252 | South Africa | ART clinic | 100 | 515 | 81 | 22.2 (13.3–33.6) | 58.3 (46.1–69.8) |

| O’Grady, 20129 | Zambia | Medical admissions able to produce sputum | 65 | 881 | 201 | 52.8 (45.1–60.4): HIV+ 48.6 (33.0–64.4): HIV− |

88.2 (81.9–92.6): HIV− 74.3 (56.4–87.0): HIV− |

| Dorman, 201249 | South Africa | Prevalence survey | ND | 6893 | 187 | 17.6 (12.5–23.9): HIV+ | 62.6 (55.2–69.5) |

| Ntinginya 201251 | Tanzania | Household contacts | ND | 219 | 5 | 60.0 (14.7–94.7): HIV− | 100 (47.8–100) |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy; ND = not done.

LAM is a Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell-wall polysaccharide that can be detected in the urine of TB patients, and is now available as a point-of-care lateral flow assay.29 It is a useful screening test in PLHIV with advanced immunosuppression, diagnosing disseminated disease that tends to smear-negative. Its low sensitivity and suboptimal specificity limit the value of the test in patients with CD4 count of >200 cells/mm.29 LAM has marked prognostic significance predictive of high mortality, and a number of clinical trials are ongoing in South Africa and Uganda.

MANAGEMENT OF HIV AND TUBERCULOSIS IN SCREENING PARTICIPANTS

Integrating TB screening with HIV testing and care

TB screening during HIV care (Figure 1) is a high priority from multiple different perspectives, and the subject of recent comprehensive and systematic reviews.18,75 Screening newly diagnosed PLHIV targets a patient group with a high prevalence of undiagnosed TB disease, indications for IPT, high vulnerability to rapidly progressive TB with a fatal outcome and collective vulnerability to nosocomial transmission through a shared respiratory contact network at the HIV care clinic. Intensive TB screening with Xpert MTB/RIF and culture can increase pre-ART identification of TB patients dramatically,30,31,39,50,78 leading to a low incidence of TB in the subsequent 12 months. Tests with pronounced prognostic significance include detectable bacilli or antigen in urine or blood which identify individuals with high risk of early death.39,55

How best to integrate HIV testing and care into TB screening interventions delivered outside of HIV programmes is less well defined. At a minimum, it is essential to confirm positive TB screening results and ensure that patients are promptly linked into TB care, with diagnostic HIV testing offered to all TB patients and participants with TB symptoms. As routine programmes lose about 15% of their newly diagnosed smear-positive TB patients and over 70% of newly diagnosed HIV-positive patients before any treatment is provided, care needs to be taken to avoid loss to follow-up between diagnosis and treatment. Loss to follow-up can be much higher when the diagnosis is made outside the routine setting, undermining the effectiveness of TB-HIV screening.41

ART is by far the most effective method of preventing HIV-related TB, with a 65% reduction in incidence, rising to 84% if the CD4 count is <200 cells/mm.11,79 Irrespective of their final diagnosis, people identified as having symptoms of TB have a high probability of being HIV-infected,22,80 being unaware of their HIV status, being eligible for ART80 and having a high risk of death if their HIV is not promptly diagnosed and treated.80–83 Indeed, in settings with generalised HIV epidemics, the NNTS to identify one patient with undiagnosed HIV is far lower than the NNTS to identify one patient with undiagnosed TB.

More completely integrated TB-HIV interventions include HIV treatment-as-prevention (TasP) strategies providing home-based HTC with TB screening and immediate ART and IPT for HIV-positive individuals,84 and combined TB and household-based HIV and TB prevention.6 ART for TasP has extremely high potential as a TB control strategy, with declining national and regional TB incidence apparent already just from routine ART scale-up.84 Eight different trials of ART for HIV prevention that include TB outcomes are currently underway or planned.85

Follow-up of suspected tuberculosis

Once TB is suspected, no diagnostic test is able to both rule-in and rule-out TB accurately.30,86 As such, it is vital to ensure continuity of care by promptly diagnosing and treating HIV infection, and by providing participants with follow-up management until TB is confirmed or excluded.80 As symptoms develop within a short time in patients with confirmed ‘sub-clinical’ TB, repeated assessment after a short interval can distinguish progressive TB disease from false-positive screening results.56

In Harare, Zimbabwe, only 20% of smear-negative ‘TB suspects’ identified in the community attended free follow-up care services.87 Participants who attended follow-up had a high prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection, a high rate of smear-negative TB diagnosis, and high mortality at 12 months during a period of very limited access to ART.80

TUBERCULOSIS SCREENING USING DIFFERENT TUBERCULOSIS ENTRY POINTS

Community-based screening for tuberculosis regardless of symptoms (entry points 1 to 3)

Community-based TB screening has not been included in international recommendations for TB control for several decades.88 Before the mid-1970s, radiological screening was widely implemented, but without clear demonstration of its impact on TB epidemiology or individual benefit.44,88 Mobile radiography is still used in some European towns to screen high-risk groups such as the homeless and drug users, with acceptable NNTS and cost-effectiveness.65,69

The South African mining industry has used annual screening since the 1930s. The onset of the HIV epidemic was associated with decreasing proportions of TB in miners diagnosed using annual CXR screening.67 TB found using screening had lower case fatality rates: an individually randomised trial of 6-monthly vs. the standard of care 12-monthly CXR screening of 2634 gold miners led to a 52% reduction in the risk of death during the first 2 months of anti-tuberculosis treatment in the more intensively screened arm.8 Radiography in miners has much lower sensitivity for culture-confirmed TB (~25%) than screening-naïve populations (>90%), potentially reflecting ‘screening escape’.89

CXR screening is highly efficient, and should be investigated in very high transmission settings, for example, combined with other intensified TB-HIV activities in South African townships where the adult prevalence of culture-positive TB is up to 4% (NNTS ~25), and for outreach screening in prisons. Another obvious application would be in facility-based screening (Figure 1).

Outreach tuberculosis screening in general communities (entry points 2 and 3)

Outreach interventions in general communities also show promise. Here the aim is to provide access to diagnosis of symptomatic TB in the community. Studies in Zimbabwe and South Africa have shown high uptake, with 2–5% smear positivity prevalence in participants.7,41 Epidemiological impact was assessed in a cluster randomised trial, with 46 neighbourhoods in Harare, Zimbabwe (DETECTB) randomised to six rounds of 6-monthly active case finding using door-to-door enquiry for chronic cough in the household or mobile van with loudspeakers.7 Participants provided sputum for smear microscopy results. Smear-positive TB case notification rates increased substantially in both arms, with the mobile van arm diagnosing the most smear-positive TB. There was a substantial and highly significant reduction in population-level culture-positive TB (before:after adjusted reduction of 41% over 2.5 years, from 7.9 per 1000 adult residents). An estimated 15–25% of undiagnosed smear-positive residents were diagnosed at each intervention round,7,21 despite the intrinsic limitations of using a low sensitivity screening algorithm (chronic cough and microscopy7).

In contrast, a large cluster multifactorial randomised trial of 24 communities in Zambia and South Africa provided with 3 years of 1) enhanced case finding (ECF) in the community, and 2) household intervention,22,43 did not show any epidemiological benefit from the ECF intervention despite considerable participation. DETECTB and ZAMSTAR (Zambia South Africa TB and HIV Reduction) ECF were complex interventions with several differences: there was less focus on direct sputum collection in ZAMSTARECF, and DETECTB included dedicated follow-up clinics for smear-negative patients and active tracing of smear-positive patients.

TB REACH, a case-finding initiative funded by the Canadian International Development Agency and coordinated by the WHO, is also providing numerous examples of highly successful TB screening interventions,15,90–93 including a number of interventions using Xpert supported by UNITAID. So far the emphasis has been on increasing case detection, rather than follow-up, to show declining TB incidence trends.

Combined TB-HIV household contact tracing interventions (entry point 4)

Household contacts of TB patients are at high risk for undiagnosed TB,40,94 with two recent meta-analyses reporting a median yield of undiagnosed TB of 3.1% and 4.5%.40,94 Pronounced heterogeneity by region and screening algorithms was noted, with one recent study showing very high rates of subclinical culture-positive disease (Shapiro in Table 2).24

According to conventional wisdom, intensive household contact tracing has limited potential to affect TB epidemiology, although of high individual benefit, as only about 10% of TB patients report household TB exposure.35 However, this has been challenged by a recent study (ZAMSTAR) that showed significant (22%) reduction in undiagnosed culture-positive TB in the general community through a cluster randomised trial that combined TB screening, HIV testing and prevention counselling in Zambia and South Africa (‘ZAMSTAR’ Household Arm6). The intervention was intensive, with three separate visits over the course of 12 months. Fitting of mathematical models to trial data suggests diffusion of indirect benefits beyond households directly covered by the intervention.43 The major challenge of timely contact screening is the need for efficient communications, transportation and a means of interacting with the community.

Broader facility-based tuberculosis screening (entry point 5)

Relatively few studies have assessed systematic screening of general out-patient clinic or primary care clinic attendees for TB in HIV-prevalent settings;9 however, there are many reasons for prioritising intensified screening for this entry point: first, it is a natural extension of TB screening provided in HIV care settings, as general clinic attendees have high HIV prevalence and high rates of undiagnosed TB.9 Second, it is an opportunity to strengthen provider-initiated HTC,95 and numerous studies have shown poor identification and management of people with TB symptoms in routine systems. Finally, screening all facility attendees for cough is already part of infection control policy.96 A recent intervention in the low HIV prevalence country of Pakistan greatly increased case notification rates using lay volunteers to provide out-patient screening, based around a mobile phone system for communication and payment of incentives.97

Facility-based interventions have the potential for population-level impact if they are implemented well enough. The first clear example of this was from Cape Town, South Africa, where a substantial fall in undiagnosed TB was reported for a community served by an unusually strong TB-HIV health clinic.12

COSTS, COST-EFFECTIVENESS AND MATHEMATICAL MODELLING OF TUBERCULOSIS SCREENING INTERVENTIONS

An increasing number of studies are estimating full screening costs and the cost-effectiveness of TB screening. Costs per participant found to have TB are higher for TB screening than for patient-initiated diagnosis: for example, US$1117 per patient41 in a South African community-based TB screening intervention and approximately US$809 under the various interventions funded through the TB REACH initiative.15 However, these estimates do not include costs averted, for example, from managing patients found at an earlier stage of disease, nor from episodes of disease and death averted. Costs incurred through false-positive diagnoses also need to be included. Even relatively small per-patient costs will require substantial additional funding to be affordable by national TB control programmes in low-income countries.98 Effective targeting to high TB prevalence risk groups and populations will be critical for maximising cost-effectiveness.44

KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND RESEARCH PRIORITIES IN TUBERCULOSIS SCREENING

Major gaps in our knowledge remain. For community-based interventions, these gaps lie in some critical areas.44 It is still unclear to what extent TB screening can contribute to reduced TB transmission, and, if so, how intensively, how often and for how long TB screening interventions have to be delivered before appreciable gains are seen.36,99,100 The nature and impact of critical health system constraints is also poorly defined, as are individual risks and benefits from TB s screening, both for PLHIV and for HIV-negative participants.

Addressing our current knowledge gaps requires operational and public health research with appropriate impact evaluation,101–103 and linked mathematical and economic modelling. Understanding the impact of screening on ‘patient-important outcomes’ such as survival and well-being, and population-level epidemiological impact are critical in guiding choices and investment.44,46,104 Mathematical modelling can identify and clarify important key principles, identify misconceptions, constraints and theoretical limitations, as well as being a tool to guide realistic study design, cost-effectiveness and provide fuller analysis and projection of real-life data.36,84,99,100,105

Among our most pressing needs are new diagnostics: a highly sensitive, portable, low-cost, point-of-care diagnostic able to ‘rule out’ TB effectively would revolutionise TB screening at all levels of the health system and community and allow rapid scale-up of HIV testing. Furthermore, tools to enable efficient population-level impact evaluation, such as robust and low-cost tests for recent TB infection able to evaluate transmission rates in communities and quantify facility-level infection control are desperately needed (Table 4).7,22,30,31,39,43,58,78,101,103,106

Table 4.

Approaches to impact evaluation for TB screening interventions (adapted from102)

| Impact being evaluated | Study designs | Expected outputs and examples |

|---|---|---|

| Any high-risk group | ||

| Comparison of performance characteristics between different tests and algorithms | Cross-sectional studies evaluating new TB diagnostics | Estimates sensitivity and specificity; can inform on robustness of new diagnostic systems in resource-poor settings30,31,78 Provides number-needed-to-screen per TB patient diagnosed in different populations |

| HIV care clinics and household contacts | ||

| Direct cohort follow-up to evaluate patient-important outcomes following screening | Cohort studies comparing outcomes according to whether or not/how screened Appropriate comparator populations provided by randomisation (e.g., step-wedge), or historical or non-randomly selected comparison cohorts |

Outcomes post-screening can include numbers diagnosed with TB at and after screen, vital status, retention in care, time to TB treatment58 Cost effectiveness and consequences of false-negative and false-positive screening results can also be assessed |

| Well-defined high TB incidence populations | ||

| Time trends in TB case notification rates compared to non-intervention comparator populations | Time trend analysis for:

|

Need accurate routine case notification system; can be confounded by other changes in routine TB diagnosis/reporting Requires disaggregation of routine case notification data to subdistrict level (unless intervention is district-wide) |

| Time trends in deaths from diagnosed/undiagnosed TB | Aiming for reduced diagnosed +/− undiagnosed TB deaths ideally routine as well as intervention participants | Need complete TB registration and outcome data for diagnosed TB deaths Accurate capture of undiagnosed TB deaths requires autopsy |

| Prevalence surveys for undiagnosed TB in the general population | Repeated before-after, or cluster-randomised cross-sectional outcomes Requires very large sample sizes and consistent survey methods |

Change/difference in undiagnosed TB provides outcome (less is always better). Several recent examples7,22,39,43,107 Before:after change does not prove causality; aim for major change in short time period to provide strongest evidence104 |

| TB transmission rates | Before-after estimates, or cluster randomised cohort or cross-sectional outcomes; requires large sample sizes and consistent methods | Evidence of impact on TB transmission is an ideal outcome, but difficult to measure and so not often evaluated in high TB incidence settings; results affected by HIV status One recent example used an incidence cohort design in schoolchildren22,43 |

| TB prevalence in HIV-infected patients | Assessed through repeated before-after design, regular surveillance with time trends, or cluster-randomised cross-sectional outcomes New clinic attendees, or routine post-mortem |

A key indicator of population-level TB control, and also the main target of prevention for TB-HIV interventions Occurs at high prevalence and clearly linked to TB transmission |

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Without a TB equivalent for HIV-incidence assays, large cohorts, repeated cross-sectional measurements or analysis of time trends in TB incidence are required to measure trends in TB control (Table 4). These are not only expensive, but also often fail to deliver clear answers due to the logistical difficulties of this kind of indirect evaluation. Demonstration projects providing high-intensity, high-coverage combined TB-HIV screening interventions could provide relatively rapid insight into which approaches to TB screening are most effective in very high TB incidence settings. Both facility- and community-based interventions need to be investigated for their acceptability and potential impact on the population, including settings with high MDR-TB rates.84,107 Intervention design should resist the temptation to over-emphasise sustainability and test low-intensity complex interventions without first establishing effectiveness.

Without clear evidence to guide policy and practice, resources may be wasted on ineffective interventions, and, conversely, the value of effective interventions may be grossly under-estimated. The need to establish effectiveness is most pressing for community-wide interventions, where costs and potential harms, but also potential benefits, are at their highest, and where contemporary examples with impact evaluation have given conflicting results.7,43

Important operational questions include linkage and retention in TB-HIV care when screening individuals not already in chronic care services. Health systems research priorities include the feasibility of provider-initiated TB and HIV screening at the facility level, and models of delivering interventions through community-directed approaches.96,108,109

CONCLUSIONS

In high HIV prevalence settings with high rates of morbidity and mortality from TB, the evidence for pursuing much bolder TB screening policy and practice is compelling, despite high cost and many remaining unknowns. Facility-based TB screening and screening of household contacts should be greatly intensified, while developing evidence around community-based interventions. As with HIV testing, a combination approach adapted to the local epidemiology will be needed. Gains from each TB infection averted are unusually high in the highly vulnerable HIV-infected members of the community, and the costs of TB screening are small compared to expenditure on HIV care.

Effective intervention with the limited diagnostics available today will have to start without clear evidence, but with investment in research to support impact evaluation, ideally at individual, clinic, facility and population level. More innovative approaches to defining and responding to needs include, for example, combined surveillance-response strategies used for targeting efforts against other major infectious diseases.110 Geospatial and molecular epidemiology could allow us to capitalise on existing epidemiological, demographic, health service resource usage data.111

Combined TB and HIV interventions are essential if any gains made through TB screening are to be maintained in high HIV prevalence settings, and they require joint planning, implementation and financing from the early stages of planning. Effective linkage to treatment and prevention of both TB and HIV needs to be the focus of special attention for both TB and HIV screening. We cannot continue to tolerate high rates of undiagnosed TB in communities and health facilities, but need to act in proportion to the threat to health and wellbeing: the magnitude and consequences of XDR-TB and MDR-TB epidemics in South Africa provide a graphic illustration of the huge cost of failure to implement effective TB and HIV screening and care.

Acknowledgements

ELC and PM are funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant nos. WT091769 and WT089673, respectively).

Footnotes

[A version in French of this article is available from the Editorial Office in Paris and from the Union website www.theunion.org]

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis report. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.6. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368:1575–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vella V, Racalbuto V, Guerra R, et al. Household contact investigation of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1170–1175. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox JA, Lukande RL, Lucas S, Nelson AM, Van Marck E, Colebunders R. Autopsy causes of death in HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa and correlation with clinical diagnoses. AIDS Rev. 2010;12:183–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen T, Murray M, Wallengren K, Alvarez GG, Samuel EY, Wilson D. The prevalence and drug sensitivity of tuberculosis among patients dying in hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a postmortem study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayles H, the ZAMSTAR Study Team A household-based HIV and TB intervention increases HIV testing in households and reduces prevalence of TB at the community level: the ZAMSTAR Community Randomized Trial. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA, USA. 5–8 March 2012; [Abstract 149bLB] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett EL, Bandason T, Duong T, et al. Comparison of two active case-finding strategies for community-based diagnosis of symptomatic smear-positive tuberculosis and control of infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe (DETECTB): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1244–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churchyard GJ, Fielding K, Roux S, et al. Twelve-monthly versus six-monthly radiological screening for active case-finding of tuberculosis: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2011;66:134–139. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.139048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Grady J, Bates M, Chilukutu L, et al. Evaluation of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay at a tertiary care referral hospital in a setting where tuberculosis and HIV infection are highly endemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Churchyard GJ, Fielding KL, Lewis JJ, et al. Cluster-randomised trial of community-wide isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis control among gold miners in South Africa: the Thibela TB study. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA, USA. 5–8 March 2012; CROI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suthar AB, Lawn SD, del Amo J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of tuberculosis in adults with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Myer L, et al. Antiretroviral program associated with reduction in untreated prevalent tuberculosis in a South African township. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1080–1085. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0598OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granich R, Williams B, Montaner J. Fifteen million people on antiretroviral treatment by 2015: treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8:41–49. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835b80dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabapathy K, Van den Bergh R, Fidler S, Hayes R, Ford N. Uptake of home-based voluntary HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stop TB Partnership/The Global Fund/World Health Organization . Priorities in operational research to improve tuberculosis care and control. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . An overview of approaches, guidelines and tools. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. Early detection of tuberculosis. WHO/HTM/STB/PSI/2011.21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Getahun H, Kittikraisak W, Heilig CM, et al. Development of a standardized screening rule for tuberculosis in people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings: individual participant data meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Boon S, White NW, van Lill SWP, et al. An evaluation of symptom and chest radiographic screening in tuberculosis prevalence surveys. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:876–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood R, Middelkoop K, Myer L, et al. Undiagnosed tuberculosis in a community with high HIV prevalence: implications for tuberculosis control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:87–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-759OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbett EL, Bandason T, Cheung Y-B, et al. Prevalent infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe: burden, risk factors and implications for control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1231–1237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayles H, Schaap A, Nota A, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis, HIV and respiratory symptoms in two Zambian communities: implications for tuberculosis control in the era of HIV. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van’t Hoog AH, Laserson KF, Githui WA, et al. High prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis and inadequate case finding in rural western Kenya. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1245–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro AE, Variava E, Rakgokong MH, et al. Community-based targeted case finding for tuberculosis and HIV in household contacts of patients with tuberculosis in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1110–1116. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1941OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbett EL, Charalambous S, Moloi VM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and the prevalence of undiagnosed tuberculosis in African gold miners. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:673–679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-590OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corbett EL, Bandason T, Cheung YB, et al. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence population provided with enhanced diagnosis of symptomatic disease. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann CJ, Variava E, Rakgokong M, et al. High prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis but low sensitivity of symptom screening among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah S, Demissie M, Lambert L, et al. Intensified tuberculosis case finding among HIV-infected persons from a voluntary counseling and testing center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:537–545. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318196761c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawn SD, Edwards DJ, Kranzer K, Vogt M, Bekker LG, Wood R. Urine lipoarabinomannan assay for tuberculosis screening before antiretroviral therapy diagnostic yield and association with immune reconstitution disease. AIDS. 2009;23:1875–1880. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32832e05c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cain KP, McCarthy KD, Heilig CM, et al. An algorithm for tuberculosis screening and diagnosis in people with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:707–716. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassett IV, Wang B, Chetty S, et al. Intensive tuberculosis screening for HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:823–829. doi: 10.1086/656282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fourie PB, Gatner EM, Glatthaar E, Kleeberg HH. Follow-up tuberculosis prevalence survey of Transkei. Tubercle. 1980;61:71–79. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(80)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roelsgaard E, Iversen E, Blocher C. Tuberculosis in tropical Africa: an epidemiological study. Bull World Health Organ. 1964;30:459–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard AA, Gasana M, Getahun H, et al. PEPFAR support for the scaling up of collaborative TB/HIV activities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(Suppl 3):S136–S144. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825cfe8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2240–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowdy DW, Basu S, Andrews JR. Is passive diagnosis enough? The impact of subclinical disease on diagnostic strategies for tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:543–551. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1217OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedell RA, Anderson ST, van Lettow M, et al. High prevalence of tuberculosis and serious bloodstream infections in ambulatory individuals presenting for antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kranzer K, Houben RMGJ, Glynn JR, Bekker LG, Wood R, Lawn SD. Yield of HIV-associated tuberculosis during intensified case finding in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:93–102. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kufa T, Mngomezulu V, Charalambous S, et al. Undiagnosed tuberculosis among HIV clinic attendees: association with antiretroviral therapy and implications for intensified case finding, isoniazid preventive therapy, and infection control. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:22–28. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318251ae0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marks GB. Active case finding in contacts of people with tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online) 2011;(9):CD008477. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008477.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kranzer K, Lawn SD, Meyer-Rath G, et al. Feasibility, yield, and cost of active tuberculosis case finding linked to a mobile HIV service in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekandi JN, Neuhauser D, Smyth K, Whalen CC. Active case finding of undetected tuberculosis among chronic coughers in a slum setting in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:508–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The ZAMSTAR Study Team The ZAMSTAR Study—community and household interventions to reduce tuberculosis in Zambian and South African communities. 42nd World Conference on Lung Health of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; Lille, France. 26–30 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kranzer K, Afnan-Holmes H, Tomlin K, et al. The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:432–446. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lönnroth K, Corbett E, Golub J, et al. Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: rationale, definitions and key considerations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:289–298. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cobelens F, van den Hof S, Pai M, Squire SB, Ramsay A, Kimerling ME. Which new diagnostics for tuberculosis, and when? J Infect Dis. 2012;205(Suppl 2):S191–S198. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNerney R, Maeurer M, Abubakar I, et al. Tuberculosis diagnostics and biomarkers: needs, challenges, recent advances, and opportunities. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(Suppl 2):S147–S158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van’t Hoog AH. Sensitivity and specificity of different TB screening tools and approaches: a systematic review. 43rd Union World Conference on Lung Health; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 13–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dorman SE, Chihota VN, Lewis JJ, et al. Performance characteristics of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF test in a tuberculosis prevalence survey. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawn SD, Brooks SV, Kranzer K, et al. Screening for HIV-associated tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance before anti-retroviral therapy using the Xpert MTB/RIF assay: a prospective study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ntinginya EN, Squire SB, Millington KA, et al. Performance of the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay in an active case-finding strategy: a pilot study from Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1468–1470. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Vogt M, Ghebrekristos Y, Whitelaw A, Wood R. Characteristics and early outcomes of patients with Xpert MTB/RIF-negative pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosed during screening before antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1071–1079. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monkongdee P, McCarthy KD, Cain KP, et al. Yield of acid-fast smear and mycobacterial culture for tuberculosis diagnosis in people with HIV. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:903–908. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0692OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walley J, Kunutsor S, Evans M, et al. Validation in Uganda of the new WHO diagnostic algorithm for smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV prevalent settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:93–100. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182243a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrews JR, Lawn SD, Rusu C, et al. The cost-effectiveness of routine tuberculosis screening with Xpert MTB/RIF prior to initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a model-based analysis. AIDS. 2012;26:987–995. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522d47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oni T, Burke R, Tsekela R, et al. High prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis in HIV-1-infected persons without advanced immunodeficiency: implications for TB screening. Thorax. 2011;66:669–673. doi: 10.1136/thx.2011.160168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ, Morroni C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2010;24:2381–2390. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833dfc68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nicholas S, Sabapathy K, Ferreyra C, Varaine F, Pujades-Rodríguez M. Incidence of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients before and after starting combined antiretroviral therapy in 8 sub-Saharan African HIV programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:311–318. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318218a713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zar HJ, Cotton MF, Strauss S, et al. Effect of isoniazid prophylaxis on mortality and incidence of tuberculosis in children with HIV: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39000.486400.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balcells ME, Thomas SL, Godfrey-Faussett P, Grant AD. Isoniazid preventive therapy and risk for resistant tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:744–751. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Halsema CL, Fielding KL, Chihota VN, et al. Tuberculosis outcomes and drug susceptibility in individuals exposed to isoniazid preventive therapy in a high HIV prevalence setting. AIDS. 2010;24:1051–1055. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833849df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Godfrey-Faussett P, Sonnenberg P, Shearer SC, et al. Tuberculosis control and molecular epidemiology in a South African gold-mining community. Lancet. 2000;356:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02730-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hogeweg L, Mol C, de Jong PA, Dawson R, Ayles H, van Ginneken B. Fusion of local and global detection systems to detect tuberculosis in chest radiographs. Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2010;13(Pt 3):650–657. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15711-0_81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Den Boon S, Bateman ED, Enarson DA, et al. Development and evaluation of a new chest radiograph reading and recording system for epidemiological surveys of tuberculosis and lung disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1088–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Story A, Aldridge RW, Abubakar I, et al. Active case finding for pulmonary tuberculosis using mobile digital chest radiography: an observational study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1461–1467. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van’t Hoog AH, Meme HK, van Deutekom H, et al. High sensitivity of chest radiograph reading by clinical officers in a tuberculosis prevalence survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1308–1314. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Churchyard GJ, Kleinschmidt I, Corbett EL, Mulder D, De Cock KM. Mycobacterial disease in South African gold miners in the era of HIV infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:791–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.World Health Organization . TB prevalence surveys: a handbook. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.17. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abubakar I, Stagg HR, Cohen T, et al. Controversies and unresolved issues in tuberculosis prevention and control: a low-burden-country perspective. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(Suppl 2):S293–S300. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dawson R, Masuka P, Edwards DJ, et al. Chest radiograph reading and recording system: evaluation for tuberculosis screening in patients with advanced HIV. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:52–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Agizew TB, Arwady MA, Yoon JC, et al. Tuberculosis in a symptomatic HIV-infected adults with abnormal chest radio-graphs screened for tuberculosis prevention. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mosimaneotsile B, Talbot EA, Moeti TL, et al. Value of chest radiography in a tuberculosis prevention programme for HIV-infected people, Botswana. Lancet. 2003;362:1551–1552. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samandari T, Bishai D, Luteijn M, et al. Costs and consequences of additional chest X-ray in a tuberculosis prevention program in Botswana. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;183:1103–1111. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0620OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization . Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF system: policy statement. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lawn SD, Mwaba P, Bates M, et al. Advances in tuberculosis diagnostics: the Xpert MTB/RIF assay and future prospects for a point-of-care test. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:349–361. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Menzies NA, Cohen T, Lin HH, Murray M, Salomon JA. Population health impact and cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis diagnosis with Xpert MTB/RIF: a dynamic simulation and economic evaluation. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vassall A, van Kampen S, Sohn H, et al. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis with the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in high burden countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lawn SD, Kranzer K, Edwards DJ, McNally M, Bekker LG, Wood R. Tuberculosis during the first year of antiretroviral therapy in a South African cohort using an intensive pretreatment screening strategy. AIDS. 2010;24:1323–1328. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283390dd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Meintjes G, Getahun H, Havlir DV, Wood R. Reducing deaths from tuberculosis in antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2012;26:2121–2133. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283565dd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.MacPherson P, Dimairo M, Bandason T, et al. Risk factors for mortality in smear-negative tuberculosis suspects: a cohort study in Harare, Zimbabwe. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1390–1396. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kyeyune R, den Boon S, Cattamanchi A, et al. Causes of early mortality in HIV-infected TB suspects in an East African referral hospital. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:446–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181eb611a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stuart-Clark H, Vorajee N, Zuma S, et al. Twelve-month outcomes of patients admitted to the acute general medical service at Groote Schuur Hospital. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:549–553. doi: 10.7196/samj.5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Westreich D, Fox MP, Van Rie A, Maskew M. Prevalent tuberculosis and mortality among HAART initiators. AIDS. 2012;26:770–773. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f6b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams BG, Granich R, De Cock KM, Glaziou P, Sharma A, Dye C. Antiretroviral therapy for tuberculosis control in nine African countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19485–19489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005660107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Granich R, Gupta S, Suthar AB, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in prevention of HIV and TB: update on current research efforts. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9:446–469. doi: 10.2174/157016211798038597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Getahun H, Harrington M, O’Brien R, Nunn P. Diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in people with HIV infection or AIDS in resource-constrained settings: informing urgent policy changes. Lancet. 2007;369:2042–2049. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dimairo M, MacPherson P, Bandason T, et al. The risk and timing of tuberculosis diagnosed in smear-negative TB suspects: a 12-month cohort study in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Golub JE, Mohan CI, Comstock GW, Chaisson RE. Active case finding of tuberculosis: historical perspective and future prospects. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1183–1203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lewis JJ, Charalambous S, Day JH, et al. HIV infection does not affect active case finding of tuberculosis in South African gold miners. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1271–1278. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-846OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Datiko DG, Lindtjorn B. Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case detection and treatment success in southern Ethiopia: a community randomized trial. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lugada E, Millar D, Haskew J, et al. Rapid implementation of an integrated large-scale HIV counseling and testing, malaria, and diarrhea prevention campaign in rural Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simwaka BN, Theobald S, Willets A, et al. Acceptability and effectiveness of the storekeeper-based TB referral system for TB suspects in sub-districts of Lilongwe in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Suthar AB, Klinkenberg E, Ramsay A, et al. Community-based multi-disease prevention campaigns for controlling human immunodeficiency virus-associated tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:430–436. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morrison J, Pai M, Hopewell PC. Tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection in close contacts of people with pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:359–368. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Sweat MD, Okero FA, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1571–1590. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0241-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.World Health Organization . WHO policy on TB infection control in health-care facilities, congregate settings and households. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Khan AJ, Khowaja S, Khan FS, et al. Engaging the private sector to increase tuberculosis case detection: an impact evaluation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:608–616. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Floyd K, Pantoja A. Financial resources required for tuberculosis control to achieve global targets set for 2015. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:568–576. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dodd PJ, White RG, Corbett EL. Periodic active case finding for TB: when to look? PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE. The persistence of tuberculosis in the age of DOTS: reassessing the effect of case detection. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:296–304. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.054510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dye C, Bassili A, Bierrenbach AL, et al. Measuring tuberculosis burden, trends, and the impact of control programmes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:233–243. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Medical Research Council . Developing and evaluating complex interventions. MRC; London, UK: [Accessed June 2013]. 2013. www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stop TB Partnership, World Health Organization . TB impact measurement policy and recommendations for how to assess the epidemiological burden of TB and the impact of TB control. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dowdy DW, Gounder CR, Corbett EL, Ngwira LG, Chaisson RE, Merritt MW. The ethics of testing a test: randomized trials of the health impact of diagnostic tests for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1522–1526. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lin HH, Dowdy D, Dye C, Murray M, Cohen T. The impact of new tuberculosis diagnostics on transmission: why context matters. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:739–747. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.101436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Demissie M, Zenebere B, Berhane Y, Lindtjorn B. A rapid survey to determine the prevalence of smear-positive tuberculosis in Addis Ababa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:580–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Laga M, Piot P. Prevention of sexual transmission of HIV: real results, science progressing, societies remaining behind. AIDS. 2012;26:1223–1229. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835462b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.CDI Study Group Community-directed interventions for priority health problems in Africa: results of a multicountry study. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:509–518. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Squire SB, Ramsay ARC, van den Hof S, et al. Making innovations accessible to the poor through implementation research. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:862–870. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Moonen B, Cohen JM, Snow RW, et al. Operational strategies to achieve and maintain malaria elimination. Lancet. 2010;376:1592–1603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dowdy DW, Golub JE, Chaisson RE, Saraceni V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis transmission and the role of geographic hotspots in propagating epidemics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:9557–9562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203517109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]