Abstract

Background

Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease may be attributable to biological and environmental factors as well as health care–seeking behaviors and diagnosis bias.

Objective

The goal of this pilot study was to determine whether there are gender discrepancies in diagnosis and time to present to a movement disorder specialist, and to assess whether clinical and referral factors account for these differences.

Methods

We report data on diagnosis, health care–seeking patterns, and clinical features in men and women with early Parkinson’s disease treated at a tertiary care center.

Results

A total of 109 patients with Parkinson’s disease (53 women and 56 men; median age at onset, 60.3 years) were included in this study. Although men and women did not differ in time from symptom onset to first physician visit, duration from symptom onset to movement disorder specialist visit was longer in women than in men. The expected duration from onset to movement disorder specialist visit for women was 61% greater than for men in the unadjusted model (P = 0.002).

Conclusion

There were gender differences in time to present to a movement disorder specialist in these patients with early Parkinson’s disease, and further study in larger samples is warranted.

Keywords: diagnosis, gender differences, Parkinson’s disease, referral, women

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder due to dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra that causes significant disability. Epidemiologic and clinical features of PD differ between men and women.1–3 Men are ~1.5 times more likely to develop PD than women,4–6 and differences in disease progression have also been reported. Some studies suggest that women have a more benign phenotype.7,8 Alternatively, women have been reported to have more severe parkinsonism, as shown by worse scores on the Hoehn and Yahr scale at presentation.9 Although this finding could imply that women have a more progressive phenotype, the difference in severity at initial examination may be due in part or wholly to health care delivery methods and diagnosis differences. These data highlight the importance of dissecting the relative gender disparities. Although some gender differences may be attributable to gender-related biological and environmental differences,10 some may be due to diagnosis and treatment bias or differences in health care–seeking behaviors.

If there are gender discrepancies, these may interfere with timely treatment for both motor and nonmotor features of PD. Although symptomatic treatments for PD are available, medications are needed to modify the underlying disease progression. When available, such medications would more likely be most efficacious early in the disease process, when there would be less nigral cell loss and more potential for prevention or amelioration of motor and nonmotor features. Heretofore, recruitment for early-stage trials for potential neuro-protective agents has been primarily through movement disorder neurologists, and for women to be proportionately represented in these trials they need to present to such a specialist in a timely fashion. To begin to address whether gender differences in diagnosis and referral exist, and which clinical and referral factors account for these differences, a pilot study was performed in a cohort of patients with early PD evaluated at a movement disorder center. We report here diagnosis and health care–seeking patterns, including time to visit with a movement disorder specialist.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study included patients with PD for ≤7 years who presented to the Center for Movement Disorders at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City and who agreed to participate in a study evaluating early PD. All patients gave written informed consent. Patients included in the study met diagnosis criteria for PD, as determined by at least 2 of the following signs—rest tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, or postural instability—and the presence of at least 2 of the following—markedly positive response to levodopa, asymmetric signs, asymmetry at onset, or initial symptom of tremor—and the absence of clinical characteristics or etiology of alternative diagnoses.11

Baseline information included systematic history from patient and family members present at the research visit: type and date of first motor symptom onset, date of first physician consultation about symptoms, diagnosis date, date of first neurologist visit, date of first movement disorder specialist visit, and family history of any relative diagnosed with PD. Dates were recorded to the day; when only the month was known, the date was imputed to day 15 of the month. When possible, recall of visit dates and diagnosis were compared with medical records received by the movement disorder specialist. Records of patient’s visit at diagnosis (51.4% [56 of 109]) and at first movement disorder specialist (71.6% [78 of 109]) were available in a subset. At baseline visit, Parts I, II, and III of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)12 and Hoehn and Yahr scores13 (Part V of the UPDRS) were completed, with Part III rated by a movement disorder specialist. The UPDRS is a six part rating scale, which is frequently used to measure severity of parkinsonism. It includes sections evaluating Mentation, Behavior and Mood (Section I: total four questions), Subjective patient report of limitations on specified activities of daily living and parkinsonian features (Section II, 13 questions), Motor Examination with clinician rated severity of motor features (Section III, 14 questions), and the Hoehn and Yahr severity scale (Section V). Sections I, II and III are rated using a 0–4 ordinal scale with responses graded according to predefined criteria for each question. The Hoehn and Yahr Stage is rated from 0–V, based on distribution of parkinsonism (unilateral, bilateral and axial involvement), postural stability, and disability: Stage 0 corresponds to no signs of disease; Stage 1, to unilateral disease; Stage 2, to bilateral disease without impairment of balance; Stage 3, to mild to moderate bilateral disease with some postural instability but physically independent; and Stage 4, to severe disability, but still able to walk or stand unassisted. Stages 1.5 and 2.5 are also defined.

The χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables were performed to compare baseline clinical characteristics and referral differences between men and women. Because only the months of symptom onset and time presenting to a physician and movement disorder specialist were known for most of the patients, the duration from symptom onset to first presenting to a physician, from onset to diagnosis, and from diagnosis to first seeing a movement disorder specialist were interval censored. Parametric survival models using the Weibull distribution were fit to compare these durations between men and women. Four models were fit for each time interval considered. Model 1 was an unadjusted comparison between men and women. In model 2, the historical features of age at onset and family history were included. In model 3, severity of disease (as measured by using the Hoehn and Yahr score) was included. Finally, model 4 included both historical and examination features (SAS version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Models 2 to 4 all included education (dichotomized at the median of 16 years).

RESULTS

A total of 109 patients with PD (53 women and 56 men; median age at onset, 60.3 years) were included in this study. Historical features are described in Table I. Rest tremor was the initial motor feature in 65.1% of men and women. There was no difference in the number of men and women working at time of diagnosis (P = 0.16). However there was a borderline increased likelihood for women to report a family history of PD (37.7% vs 23.2%; P = 0.10).

Table I.

Clinical features.

| Women (n = 53) | Men (n = 56) | Total (N = 109) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical features | ||||

| Age at onset,† median (interquartile range) | 60.2 (51.6–67.1) | 60.5 (55.2–67.8) | 60.3 (53.6–67.1) | 0.48 |

| Symptoms at onset, no. (%) | ||||

| Rest tremor | 34 (64.2%) | 37 (66.1%) | 71 (65.1%) | 0.83 |

| Gait | 8 (15.1%) | 5 (8.9%) | 13 (11.9%) | 0.32 |

| Rigidity | 4 (7.6%) | 10 (17.9%) | 14 (12.8%) | 0.11 |

| Bradykinesia | 3 (5.7%) | 2 (3.6%) | 5 (4.6%) | 0.67 |

| Other motor‡ | 4 (7.6%) | 2 (3.6%) | 6 (5.5%) | 0.43 |

| Employed at time of diagnosis, no. (%) | 30 (56.6%) | 39 (69.6%) | 69 (63.3%) | 0.16 |

| Family history, no. (%) | 20 (37.7%) | 13 (23.2%) | 33 (30.3%) | 0.10 |

| Education (>16 years), no. (%) | 35 (72.9%) | 43 (78.2%) | 78 (75.5%) | 0.53 |

| Clinical features at first movement disorder specialist examination | ||||

| Age at examination, y | 63.5 (54.9–70.0) | 62.7 (57.2–69.6) | 63.1 (56.0–69.8) | 0.80 |

| Duration since onset, y | 1.95 (1.13–4.12) | 1.28 (0.57–2.47) | 1.58 (0.78–2.88) | 0.006 |

| Motor UPDRS | 8.5 (5.5–14) | 10 (7–15) | 9 (6.3–15) | 0.25 |

| Total rest tremor | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.61 |

| Total rigidity | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3.5) | 0.06 |

| Total bradykinesia | 3 (2–5.5) | 3.5 (2.3–5.3) | 3 (2–5.5) | 0.45 |

| Postural instability | 1 (.5–2) | .5 (0–1.3) | 1 (0–1.5) | 0.06 |

| Receiving any anti-parkinsonian agent, no. (%) | 41 (77.4%) | 42 (75.0%) | 83 (76.2%) | 0.83 |

| Receiving agonist or levodopa therapy, no. (%) | 33 (62.3%) | 35 (62.5%) | 68 (62.4%) | 1.00 |

| Receiving levodopa, no. (%) | 23 (43.4%) | 14 (25.0%) | 37 (33.9%) | 0.04 |

| Levodopa dose, mg | 300 (275–400) | 300 (150–400) | 300 (275–400) | 0.37 |

| Levodopa-equivalent dose, mg | 300 (200–400.0) | 201 (134–300) | 225 (143.8–387.5) | 0.05 |

| MMSE score | 30 (29–30) | 30 (29–30) | 30 (29–30) | 0.77 |

| UPDRS Motivation and Depression >0 | 50.9% | 33.9% | 42.2% | 0.08 |

| UPDRS Part 1 | 1 (0–2) | .5 (0–1) | .5 (0–1.5) | 0.16 |

| UPDRS Part 2 | 4 (2.5–6.5) | 4.5 (2.5–5.8) | 4.5 (2.5–6) | 0.88 |

| Hoehn and Yahr score | 2 (2–2.5) | 2 (2– 2) | 2 (2– 2) | 0.01 |

MMSE = Mini–Mental State Examination; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Comparison between rest tremor or other symptom at onset for men and women.

The χ2 test and the Fisher exact test were used for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables.

Onset of first motor symptoms; no women and 2 men complained of nonmotor symptoms as first symptoms.

Other motor symptoms include weakness of limbs, change in writing, change in voice, and decreased facial expression.

Clinical characteristics at study enrollment are also presented in Table I. There was a borderline significantly longer duration of disease for women at time of examination (median, 3.1 vs 2.6 years; P = 0.081). Women were younger at symptom onset (median, 60.2 vs 60.5 years) and at study enrollment (median, 63.9 vs 64.5 years). Women were more likely to have higher stage of disease, as measured by using the Hoehn and Yahr score (P = 0.025). Women were also more likely to be receiving levodopa therapy (P = 0.05). However, neither of these factors was significant when adjusted for duration of disease in linear regression models.

Results comparing health care and diagnosis pattern duration times between women and men from survival models are presented in Table II. Overall, it took women longer from onset of symptoms to first movement disorder specialist visit: the expected duration from onset to movement disorder specialist visit for women was 61% greater than for men (P = 0.003) in the unadjusted model. The effect remained similar after adjusting for Hoehn and Yahr score (model 3), with a 55% increase (P = 0.007) for women. Adjusting for historical features, including age at onset and family PD history (model 2), the magnitude of the percentage increased for women (51%; P = 0.02) and remained significant. A similar magnitude (42% increase for women; P = 0.03) was present after adjusting for both historical features (age at onset and family PD history) and Hoehn and Yahr score (model 4).

Table II.

Referral patterns.

| Women (n = 53) | Men (n = 56) | Model*

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Symptom onset to movement disorder specialist visit†,‡ (months)§ | 22.2 (10.8–39.2) | 13.7 (6.60–24.2) | 1.61 (1.84–2.20) P = 0.003 | 1.49 (1.08–2.08) P = 0.02 | 1.55 (1.13–2.14) P = 0.007 | 1.41 (1.03–1.94) P = 0.03 |

| Symptom onset to first physician visit (months) | 4.44 (1.32–11.6) | 3.36 (0.96–8.64) | 1.34 (0.75–2.26) P = 0.30 | 1.40 (0.78–2.49) P = 0.21 | 1.40 (0.78–48) P = 0.21 | 1.38 (0.76–2.49) P = 0.22 |

| First physician visit to diagnosis (months) | 3.48 (0.96–9.36) | 2.76 (0.84–7.44) | 1.27 (0.73–2.22) P = 0.40 | 1.31 (0.73–2.35) P = 0.37 | 1.37 (0.77–2.46) P = 0.28 | 1.36 (0.75–2.44) P = 0.31 |

| Symptom onset to diagnosis (months) | 12.7 (5.64–24.1) | 9.12 (3.96–17.3) | 1.40 (0.99–1.99) P = 0.06 | 1.30 (0.90–1.87) P = 0.14 | 1.37 (0.95–1.97) P = 0.09 | 1.30 (0.90–1.88) P = 0.15 |

| Diagnosis of PD to movement disorder specialist visit (months) | 7.44 (2.28–19.2) | 4.44 (1.32–11.4) | 1.80 (0.91–3.15) P = 0.06 | 1.78 (0.84–3.09) P = 0.08 | 1.70 (0.82–2.76) P = 0.08 | 1.45 (0.69–2.40) P = 0.23 |

Model 1 = unadjusted; Model 2 = adjusted for historical features (age of onset and family history) and education; Model 3 = adjusted for examination features (Hoehn and Yahr score) and education; and Model 4 = adjusted for historical and examination features and education.

Percentage with estimated referral dates when only the month was known. For those time points, date was imputed to day 15 of the month. All patients recalled month but not day of symptom onset; 20.2% (22 of 109) estimated movement disorder specialist date (22.6% [12 of 53] of women, 17.9% [10 of 56] of men); 84.2% (85 of 101) estimated first physician date (88% [44 of 50] of women, 80.4% [41 of 51] of men); 57.8% (63 of 109) estimated diagnosis date (62.3% [33 of 53] of women, 53.6% [30 of 56] of men).

Values are given as median duration years (interquartile range).

Values are given as estimate of female/ male ratio, (95% CI), and P value.

In evaluating the different phases to visit by a movement disorder specialist, there was a borderline significantly longer duration from onset to diagnosis for women compared with men, with the expected duration from onset to diagnosis for women 41% greater than for men (P = 0.06) in the unadjusted model. The effect remained similar after adjusting for the Hoehn and Yahr score (model 3), with a 38% increase (P = 0.09) for women. Adjusting for historical features, including age at onset and family PD history (model 2), the magnitude of the percentage increased for women (32%; P = 0.14) was slightly reduced but similar to the unadjusted model. A similar but nonsignificant difference (32% increase for women; P = 0.15) was found after adjusting for both historical features (age at onset and family PD history) and Hoehn and Yahr score (model 4). There was also a borderline significantly longer duration from diagnosis to first movement disorder specialist visit among women compared with men, with the expected duration for women 80% greater than for men (P = 0.06) in the unadjusted model, which persisted in model 2 (78% longer) and model 3 (70% longer) (both, P = 0.08). This effect was not present in the combined models adjusting for historical and examination features (model 4, 45% longer; P = 0.23). When separated into the duration from onset to first physician visit, as well as first physician visit to diagnosis, women did not have a significant delay compared with men.

DISCUSSION

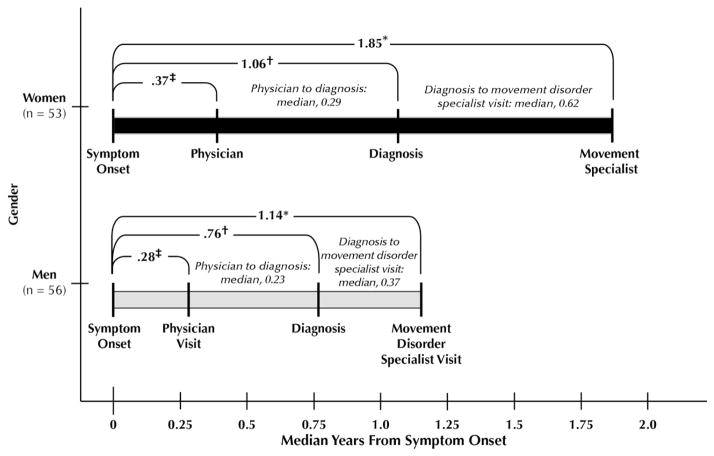

In our sample of patients with PD recruited from a US movement disorder center, we found that women experienced a delay in presenting to the movement disorder specialist. This gender difference persisted after adjusting for clinical features. Although the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was longer for women and likely contributed to the referral delay, this finding was not significant. Indeed, there was a suggestion of mild delay in all steps toward diagnosis and treatment by movement disorder specialists (schematically shown in the Figure). We hypothesize that gender difference in time from symptom onset to first visit to a movement disorder specialist is likely multifactorial, and although differences in disease progression and family history may contribute, these factors do not fully account for the longer time it takes for women present to a movement disorder specialist.

Figure.

Schematic demonstrating the median years from symptom onset to outcomes. Median times from physician visit to diagnosis and diagnosis to movement disorder specialist visit are noted in parentheses in the schema. * Onset to physician visit (men compared with women, Mann-Whitney test [unadjusted]), P = 0.34. †Onset to diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (unadjusted, P = 0.06). ‡Onset to movement disorder specialist visit (unadjusted, P = 0.002).

Gender difference in incidence of PD and the higher rates of dyskinesias among women are well accepted, yet gender-related discrepancies in phenotype and health care–seeking patterns vary across studies.14 Some researchers postulate that women have a more benign phenotype, presenting at an older age, with more rest tremor and less nigrostriatal dysfunction on single-photon emission computed tomography imaging.7 Another study did not find a difference in age at onset but noted that women are more likely to be depressed and have greater postural instability when adjusted for disease duration.15 Alternatively, it was proposed that women experience disease onset later because they have a slower preclinical course but do not differ significantly once PD is present.4 It has been postulated that the milder early progression may be due to hormonal benefits that are most prominent early in a woman’s life but decrease postmenopausally.1,16

Differences in progression were not directly measured in this cross-sectional study, but the only clinical difference at visit to a movement disorder specialist was the greater Hoehn and Yahr score in women. However, when adjusted for duration of disease, even Hoehn and Yahr scores did not differ between the sexes. Furthermore, when the Hoehn and Yahr score was included in the model, the delay to presenting to a movement disorder specialist was maintained. Our data do not, therefore, support prior hypotheses that clinical differences are responsible for the diagnosis or referral delay. Thus, although we cannot exclude that subtle differences in the rate of progression contributed to the delay in diagnosis or referral in women, they likely do not fully account for these trends because gender differences persisted even when measures of disease severity were included in the multivariate models.

In evaluating other factors that may be associated with gender differences, it is of interest to note that the percentage of women working at the time of diagnosis was not different from men, thus making it unlikely that employment concerns led to earlier diagnosis. It remains possible that men were performing work that was potentially more limited by their PD. We also cannot exclude the possibility that the difference in time to diagnosis may be attributable to additional unmeasured features. Women may be aware of symptoms earlier, yet less likely to emphasize these during medical examinations. Nonspecific or nonmotor PD symptoms such as muscle pain or depression may be prominent,17 and hence misdiagnosed, for longer periods of time in women. Although our study focused on motor features, nonmotor symptoms including constipation,18,19 sleep disturbances,20 and mood changes and anxiety21,22 may be the earliest harbingers of disease. Furthermore, increased rates of REM sleep behavior disorder among men compared with women, before PD onset,23 suggest that autonomic disturbances may present differentially according to gender. Although nonmotor symptoms should be considered in further studies of early PD and gender, and may also impact early identification of subjects for disease-modifying trials, we were unable to assess this factor in our group because these features were not systematically recorded before disease onset.

There was a suggestion, albeit of borderline significance, that women were more likely to report any positive family history of PD. This finding may also contribute to earlier awareness of symptoms in women; however, regardless of gender, family history was not associated with a shorter delay to diagnosis, and the female/male ratio in the delay from onset to diagnosis, and diagnosis to movement disorder specialist visit, did not significantly change with inclusion of family history in the model. Delays in diagnosis of PD in women may be due to physicians’ predisposed perceptions that PD is more likely to occur in men, which is in contrast to other neurologic diseases such as migraine or multiple sclerosis that are more frequent in women.24–26 A strength of our study is that patients were early in the course of disease and hence less likely to have recall bias of the onset of symptoms and diagnosis.

An important limitation of this study is that individuals were evaluated at a tertiary care center, and no central repository of information regarding medical utilization before the diagnosis of PD was available. Thus, there may be differential recall between men and women that has not been accounted for. As our sample was a highly educated tertiary care sample, it may not be representative of those treated by internists and general neurologists, who never seek care with a movement disorder specialist. However, we did target the group of women mostly likely to be enrolled in an early-stage trial; that is, those being seen by movement disorder specialist.27–29 Although education has been shown to affect recall of onset in another movement disorder (dystonia30), education did not differ significantly between the groups and was included in the models; it therefore did not account for gender differences. We did not have information regarding income, which might have provided further insight. It is a drawback to our pilot study that the sample size was small, and it was limited to tertiary care referral cases. Therefore, referral differences based on gender should be addressed in larger, more definitive records-based and/or community-based studies.

In simulated health scenarios, women are equally as likely to seek help, suggesting that, as with the present study, there are additional barriers to women accessing health care and specialist referrals.31 Roos et al9 reported that women had higher Hoehn and Yahr scores when first visiting the physician, and proposed that men seek medical advice earlier in their disease course than women. In our study, women were only delayed by several months in presenting to a physician, and this difference was not significantly different between the sexes.

CONCLUSIONS

In this pilot study, which focused on motor features in a small tertiary care sample, gender differences were noted in delay to tertiary care referral. This finding suggests that additional studies which better evaluate gender differences in early PD in community-based populations with records linked to primary care visits are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grant K23 NS047256 (to Dr. Saunders-Pullman) and the Thomas Hartman Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Dr. Saunders-Pullman was funded by a Pfizer/Society for Women’s Health Research Scholars Grant for Faculty Development in Women’s Health. She also received support for this study from the NIH: NINDS K23-NS047256, the Thomas Hartman Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. She has also received support from the Bachmann-Strauss Dystonia Parkinson’s Foundation. She is currently funded by the NIH NINDS K02-NS073836, the Marcled Foundation and the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research. Dr. Wang and Ms. Stanley have no disclosures. Dr. Bressman is funded by the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, and was funded from the NIH NS26636. The Beth Israel Dystonia Center received program support from the Bachmann-Strauss Dystonia and Parkinson’s Foundation.

The authors are grateful to Drs. Richard Lipton and Carol Derby for critical review of the manuscript.

Dr. Saunders-Pullman was responsible for the study design and conceptualization, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting and revision of the manuscript. Dr. Wang and Ms. Stanley were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data and the revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shulman LM. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. Gend Med. 2007;4:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavon JM, Whitson HE, Okun MS. Parkinson’s disease in women: a call for improved clinical studies and for comparative effectiveness research. Maturitas. 2010;65:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders-Pullman R. Estrogens and Parkinson disease: neuroprotective, symptomatic, neither, or both? Endocrine. 2003;21:81–87. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:21:1:81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alves G, Muller B, Herlofson K, et al. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Norway: the Norwegian ParkWest study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:851–857. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.168211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor KS, Cook JA, Counsell CE. Heterogeneity in male to female risk for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:905–906. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Rocca WA, et al. Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism in a longitudinal study: two-fold higher incidence in men. ILSA Working Group. Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurology. 2000;55:1358–1363. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haaxma CA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, et al. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:819–824. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.103788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons KE, Hubble JP, Troster AI, et al. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos RA, Jongen JC, van der Velde EA. Clinical course of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1996;11:236–242. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kompoliti K. Estrogen and Parkinson’s disease. Front Biosci. 2003;8:391–400. doi: 10.2741/1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward CD, Gibb WR. Research diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1990;53:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahn S, Elton RL . Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Goldstein M, Caine DB, editors. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987. pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burn DJ. Sex and Parkinson’s disease: a world of difference? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:787. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.109991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba Y, Putzke JD, Whaley NR, et al. Gender and the Parkinson’s disease phenotype. J Neurol. 2005;252:1201–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of parkinsonism in women who underwent oopherectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2008;70:200–209. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280573.30975.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott B, Borgman A, Engler H, et al. Gender differences in parkinson’s disease symptom profile. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102:37–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102001037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savica R, Carlin JM, Grossardt BR, et al. Medical records documentation of constipation preceding Parkinson disease: a case-control study. Neurology. 2009;73:1752–1758. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34af5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:456–462. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bower JH, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, et al. Anxious personality predicts an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2105–2113. doi: 10.1002/mds.23230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiba M, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders preceding Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Mov Disord. 2000;15:669–677. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200007)15:4<669::aid-mds1011>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoritaka A, Ohizumi H, Tanaka S, et al. Parkinson’s disease with and without REM sleep behaviour disorder: are there any clinical differences? Eur Neurol. 2009;61:164–170. doi: 10.1159/000189269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bigal ME, Kurth T, Santanello N, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;74:628–635. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d0cc8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin N, Mor M, Ben-Hur T. Patterns of misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:489–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson LM, Franklin GM, Hamman RF, et al. Referral bias in multiple sclerosis research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. for the Parkinson Study Group. Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. Neurology. 1990;40:1529–1534. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.10.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson Study Group PRECEPT Investigators. Mixed lineage kinease inhibitor CEP-1347 fails to delay disability in early Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1480–1490. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277648.63931.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1268–1278. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Defazio G, Abbruzzese G, Girlanda P, et al. Does sex influence age at onset in cranial-cervical and upper limb dystonia? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:265–267. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adamson J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N, et al. Ethnicity, socio-economic position and gender—do they affect reported health-care seeking behaviour? Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]