Abstract

The haloacid dehalogenase enzyme superfamily (HADSF) is largely composed of phosphatases, which, relative to members of other phosphatase families, have been particularly successful at adaptation to novel biological functions. Herein, we examine the structural basis for divergence of function in two bacterial homologs: 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate phosphohydrolase (KDO8P phosphatase, KDO8PP) and 2-keto-3-deoxy-9-O-phosphonononic acid phosphohydrolase (KDN9P phosphatase, KDN9PP). KDO8PP and KDN9PP catalyze the final step of KDO and KDN synthesis, respectively, prior to transfer to CMP to form the activated sugar nucleotide. KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs derived from an evolutionarily diverse collection of bacterial species were subjected to steady-state kinetic analysis to determine their specificities towards catalyzed KDO8P and KDN9P hydrolysis. Although each enzyme was more active with its biological substrate, the degree of selectivity (as defined by the ratio of kcat/Km for KDO8P vs. KDN9P) varied significantly. High-resolution X-ray structure determination of Haemophilus influenzae KDO8PP bound to KDO/VO3− and Bacteriodes thetaiotaomicron KDN9PP bound to KDN/VO3− revealed the substrate-binding residues. Structures of the KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs were also determined to reveal the differences in active site structure that underlies the variation in substrate preference. Bioinformatic analysis was carried out to define the sequence divergence among KDN9PP and KDO8PP orthologs. The KDN9PP orthologs were found to exist as single domain proteins or fused with the pathway nucleotidyl transferases; fusion of KDO8PP with the transferase is rare. The KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs share a stringently conserved Arg residue, which forms a salt bridge with the substrate carboxylate group. The split of the KDN9PP lineage from the KDO8PP orthologs is easily tracked by the acquisition of a Glu/Lys pair that supports KDN9P binding. Moreover, independently evolved lineages of KDO8PP orthologs exist, separated by diffuse active-site sequence boundaries. We infer high tolerance of the KDO8PP catalytic platform to amino acid replacements that, in turn, influence substrate specificity changes and thereby facilitate divergence of biological function.

Keywords: 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid (KDO), 2-keto-3-deoxynononic acid (KDN), phosphohydrolases, enzyme evolution, ortholog boundaries

The haloacid dehalogenase enzyme superfamily (HADSF) has proven to be an excellent system for examining the structural basis for the divergence of function among paired homologs within a common evolutionary clade.1-3 Hallmarks of the superfamily include its large size (>83,000 members to date in Pfam), high degree of sequence diversity, and broad substrate range.4 At the top of the HADSF hierarchy, the phosphatases (which comprise > 99 % of the family5 are divided into broad structural classes (C0, C1, C2A, C2B)4, 6 based on the location (relative to catalytic motifs), size (extended loops vs. inserted domain (termed the cap domain)) and topology of loops/domain inserts to the highly conserved Rossmann-fold catalytic domain (termed the core domain). In turn, the individual structural classes are comprised of clades,4 the members of which are closely related in structure and evolutionary history, yet perform unique biological functions. Our goal is to gain insight into the process of function change within these distinct lineages of HADSF phosphatases.

In the present study, we targeted a lineage of sequences within the “YbrI” clade of the type-C0 structural class (typical structure shown in Figure 1A and 1B).4 The biological unit is comprised of four identical Rossmann-fold subunits that oligomerize via a central β-barrel formed from the respective four β-loop-β inserts (colored yellow in Figure 1A and 1B). The active site is formed at the interface of two adjacent subunits and there are four active sites per tetramer in total. The catalytic scaffold, located at the C-terminal end of the Rossmann central parallel β-sheet contains catalytic motifs 1-4 (colored red, green, cyan and orange respectively) and the bound Mg2+ cofactor (magenta sphere). The residues located on the adjacent subunit (known as the cap subunit, analogous to the cap domain) complete the active site (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. KD9PP monomer (A) and tetramer (B) structures (PDB ID 3E8M).

HADSF Rossmann fold domain colored gray or light blue with the tetramerization flap colored yellow. HADSF catalytic motifs colored: motif 1, red; motif 2, green; motif 3, cyan; motif 4, orange; magnesium cofactor is shown in magenta. Figure (and all others unless indicated) generated with MOLSCRIPT41 and POVscript+.42

The two enzyme activities attributed to the YbrI clade are those of the 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate (KDO8P) phosphatase (KDO8PP)7, 8 and 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galacto-nonic acid-9-phosphate (KDN9P) phosphatase (KDN9PP).9 The structures of the α- and β-anomers of KDO8P and KDN9P are illustrated in Chart I. KDO is a saccharide integral to lipid A in Gram-negative bacteria and critical for survival.10-14 KDN is a 9-carbon sialic acid derivative commonly used in cell-wall polysaccharides in higher level organisms, which unexpectedly has also appeared in bacteria.15 KDO8PP and KDN9PP catalyze the final step in the synthesis of KDO and KDN which are subsequently activated with a C(1) cytosine monophosphate (CMP) group (Scheme 1). The means of conferring specificity in the KDO8PP and KDN9PP is not clear from primary sequence alignments or from examination of the available liganded structures.9, 16

Chart I.

Scheme 1.

The biosynthetic pathways leading to the cytidine monophosphate (CMP) substituted β-anomers of KDO and KDN.

The goals of this work were to define the structural basis for the divergence in substrate preference among homologs, the relationship between substrate preference and biological function, and lastly, the evolutionary pathways that determine structure and function. Steady-state kinetic constants that define substrate preference (KDO8P vs. KDN9P) of targeted YrbI clade phosphatases were determined. Next, we examined the KDO8PP and KDN9PP X-ray structures, which revealed the substrate binding motifs responsible for discrimination between KDO8P and KDN9P. The substrate specificity residues thus defined were used in combination with gene context analysis to identify KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs among homologous sequences. Based on the examination of these data, the biological ranges of KDO8PP and KDN9PP were determined and alignments of ortholog sequences, grouped according to KDO8PP and KDN9PP structural classes, were used to generate an unrooted phylogenetic tree that provides insight into the evolutionary history of KDO8PP and KDN9PP. Lastly, we propose a model for the divergence of structure and substrate preference that accompanies the adaptation of the YbrI clade scaffold to perform one of two distinct biological functions (KDO vs. KDN synthesis).

Materials and Methods

Materials, Cloning and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Unless otherwise stated all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and all primers, competent cells, ligases, polymerases, and restriction enzymes from Invitrogen. The gene encoding BT1713 (BT-KDN9PP) was previously cloned.17 The plasmid containing the coding sequence for HI1679 (HI-KDO8PP) from Haemophilus influenzae was a generous gift from Dr. Osnat Herzberg at the Center for Advanced Research in Biotechnology, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Rockville, Maryland. The gene encoding BT1677 (BT-KDO8PP) was amplified from Bacteriodes thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 genomic DNA with primers 5′CCGGCGGGGAGAATTGGAGGCTAATATAA 3′ (forward) and 5′GCTGGCAGACAGTCAGGCATTGCAGGAAAT 3′ (reverse). After amplification, the clone was modified to include restriction sites for Nde1 and BamH1 using the primers 5′ GTAAAAGCATATGAGCACCATCAATTATGATTATCCCGC 3′ (NdeI) and 5′TTATTAAAGGGATCCACAACTCACCAGCCGAAAGCATCTTCCGCC 3′ (BamHI) (bold letters indicate restriction sites). After amplification, the clone was digested with Nde1 and BamH1. The fragment was cloned into a pET15b vector containing an N-terminal His6-tag and thrombin cleavage site.

BT-KDN9PP and BT-KDO8PP genes bearing site-directed mutations were prepared by using a PCR-based strategy with primers encoding the desired codon change and native flanking sequence and the wild-type BT-KDN9PP or BT-KDO8PP plasmid serving as a template. The gene sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing (University of New Mexico sequencing facility).

Expression and Purification

Recombinant BT-KDN9PP (wild-type and mutants), and HI-KDO8PP were expressed and purified as previously described.7, 17 Recombinant BT-KDO8PP was purified from Escherichia coli BL-21(DE3) cells transformed with the pET15b vector harboring the BT-KDO8PP sequence. Cells were grown in LB media at 37 °C until A600 = 1.0 at which point IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,800 g) after 4 h. Cell pellets were suspended in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl and were then lysed by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (48,400 g) for 45 min. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 μm sterile filter and applied to a TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Clontech) gravity column (5 mL) equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES pH (7.5), 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole. BT-KDO8PP was eluted using a step gradient of imidazole (30 mM, 100 mM, 250 mM, and 500 mM). Fractions containing BT-KDO8PP were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and dialyzed against 2 L of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 1 mM DTT. The dialyzed protein was cleaved by incubating with Tagzyme DAPase (Qiagen) for 2 h at 37 °C with 250 rpm shaking. The cleavage mixture was applied to the TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Clontech) gravity column (5 mL) pre-equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole. The flow-through was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, pooled and dialyzed against 2 L of 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. Purified protein was concentrated to 30 mg/mL using an Amicon Ultra Concentrator. Typical yields were 3.8 mg protein/g cell paste. The protein was shown to be >90% pure as assessed by SDS/PAGE analysis.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Solution of BT-KDO8PP

Crystals of BT-KDO8PP were obtained by the vapor-diffusion method using hanging drop geometry. Drops were equilibrated against a reservoir solution containing 30% polyethylene glycol (PEG) MME 550, 40 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) at 18°C. The hanging drops contained equal volumes (1 μl each) of the reservoir solution and a 30 mg/mL protein solution in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl and 10 mM MgCl2. Small crystals (0.1 mm × 0.1 mm × 0.05 mm) appeared within 2 d. The crystals belonged to the space group P212121, with four protomers in the asymmetric unit and with solvent comprising 35% of the unit cell. Surface solvent was removed using Paratone, and the resulting crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at 100 K using a single wavelength (1.0 Å) at the X12C beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY). For data collection, beamline X12C was equipped with a Brandeis 2 × 2 CCD detector. Data were collected to 1.8 Å resolution and processed with the program DENZO and SCALEPACK.18

The structure of the wild-type BT-KDO8PP-Mg2+ complex was refined to 1.8 Å resolution with phases determined by the molecular replacement method using the program MOLREP in the CCP4 suite.19-21 The search model was the protomer of BT-KDN9PP (BT1713), leading to a clear solution for four protomers (forming the expected tetramer). The structure was refined using the program PHENIX22 with data between 36.7 and 1.8 Å, for which F ≥ 2σ(F) with alternating cycles of positional and individual temperature factor refinement. The resulting model was manually inspected and modified using the program COOT. In the final stages of the refinement, water molecules were added to the model using an electron-density acceptance criteria of d ≥ 3σ(d) in the Fo-Fc difference electron-density map. Magnesium ions were added in the final stage of refinement with an electron-density acceptance criteria of d ≥ 5σ(d) in the Fo-Fc map. Specific unit cell parameters, data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 2. The final model consisted of residues: Chain A, 2 – 166; Chain B, 2 – 165; Chain C, 2 – 166; Chain D, 2 – 166.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for BT-KDO8PP bound with Mg2+, BT-KDN9PP bound with Mg2+, VO3− and KDN and HI-KDO8PP bound with Mg2+, KDO and VO3−. Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell, NA indicates not applicable.

| Data Collection | BT-KDO8PP- Mg2+ | BT-KDN9PP- Mg2+-VO3−-KDN | HI-KDO8PP- Mg2+-VO3−-KDO |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PDB ID | 4HGN | 4HGO | 4HGP |

| Space group | P212121 | P21212 | I4 |

| Cell dimension (Å) | a = 37.52 b = 91.20 c = 170.07 |

a=81.30 b=106.32 c=74.15 |

a = b = 79.85 c = 52.15 |

| Molecules / ASU | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1 | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 85.1 - 1.8 (1.86 - 1.8) |

28.5 - 2.1 (2.2 - 2.1) |

29.5 - 1.8 (1.89 - 1.8) |

| Observed reflections | 261,122 | 220,160 | 120,635 |

| Unique reflections | 50,327 | 38,011 | 14,537 |

| Completeness (%) | 91.1 (79.7) | 95.5 (99.0) | 95.6 (91.4) |

| Rsyma (%) | 6.1 (43.2) | 7.6 (48.3) | 5.73 (38.13) |

| <I/σ> | 19.6 (2.79) | 6.29 (2.5) | 13.68 (2.40) |

| Redundancy | 5.3 (4.7) | 5.4 (2.73) | 7.9 (5.7) |

| Twin Law | -k,-h,-l | ||

| Twin Fraction | 0.33 | ||

|

| |||

| Refinement | |||

|

| |||

| R / Rfree | 17.56 / 21.83 | 19.02 / 24.71 | 14.73 / 16.52 |

| No. of Atoms | |||

| Protein /Water | 5064 / 329 | 5143 / 176 | 1352 / 177 |

| Mg2+ / VO3−-KDO or VO3−-KDN | 8 / NA | 4 / 52 | 1 / 36 |

| Average Temperature Factor (Å2) | |||

| Protein /Water | 23.3 / 28.6 | 22.5 / 23.1 | 18.3 / 26.0 |

| Mg2+ / VO3−-KDO or VO3−-KDN | 24.2 / NA | 24.5 / 36.5 | 15.4 / 20.5 |

| Ramachandran Statistics | |||

| Favored /Allowed / Outlier (%) | 98 / 2 / 0 | 96.6 / 3.4 / 0 | 96 / 2/ 0 |

| Rms deviation from ideal | |||

| Bonds | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.011 |

| Angles | 1.094 | 1.082 | 1.184 |

| Clashscore | 8.74 | 12.00 | 10.44 |

Rsym = Σhk1 Σi| Ihk1, i-<Ihk1> I | / Σhk1Σi | Ihk1, i |, where <Ihk1> is the mean intensity of the multiple Ihk1, i observations for symmetry-related reflections.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Solution of the BT-KDN9PP complex with KDN/VO3−

Crystals of BT-KDN9PP were obtained by the vapor-diffusion method with hanging drop geometry. Drops were equilibrated against reservoir solution containing 19% PEG 3350 and 100 mM magnesium formate at room temperature. The hanging drops contained equal volumes (1μl each) of the reservoir solution and a 29 mg/mL protein solution in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mM MgCl2. Small crystals (0.15 mm ×0.15 mm ×0.01 mm) appeared in 1 d. Crystals were soaked in a 50 μL solution of 50 mM KDN (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number 60714), 20 mM sodium vanadate (Na3VO4), 22% PEG 3350 and 100 mM magnesium formate for one week before data collection. The crystals belonged to the space group P21212. Surface solvent was removed by passing the crystal through paratone and then flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected at a single wavelength (1.54 Å) on the Bruker Microstar-H running at 2.7 kW with Helios multi-layer optics and a Platinum 135 CCD detector at Bruker AXS, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. Data were collected to 2.1 Å, reduced using SAINT and scaled using SADABS from the PROTEUM2 software suite.24

The structure of liganded BT-KDN9PP was determined by molecular replacement to 2.1 Å resolution using the program MOLREP in the CCP4 suite20 and the protomer of BT-KDN9PP as the search model. A clear solution for four protomers (the expected tetramer) was obtained. Successive rounds of model refinement were performed using the program PHENIX22 and data between 50 and 2.1 Å, for which F ≥ 2σ(F) with alternating cycles of positional and individual temperature-factor refinement. The resulting model was inspected and modified using the program COOT. In the final stages of refinement, water molecules were added to the model with electron-density acceptance criteria of d ≥ 3σ(d) in the Fo–Fc difference electron-density map. Ligands (KDN and VO3−) were added when the Rfree was below 30%. A composite-omit map with coefficients 2Fo-Fc was calculated using the program CNS. Unit-cell parameters, data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 2. The final model showed density corresponding to VO3− at all four active sites and density corresponding to KDN at two of the active sites (Figure SI12). Residues Gln164 in each chain (A, B, C, and D) was disordered and not modeled, as well as Met1 of Chain D.

The structures of BT-KDN9PP-Glu56Ala and BT-KDN9PP-Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala variants bound to the Mg2+ cofactor were also solved (see Supplemental information for crystallization, data collection, and refinement details).

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Solution of HI-KDO8PP

Crystals of KDO8PP from Haemophilus influenzae (HI-KDO8PP) were obtained by the vapor diffusion method with hanging drop geometry. Drops were equilibrated at 17°C against a reservoir solution containing 21% PEG 3550 and 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5). Hanging drops contained equal volumes (1 μl) of the reservoir solution and an 11 mg/mL solution of protein in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT. Small crystals (0.15 mm ×0.1 mm ×0.05 mm in dimension) appeared in within 1 d. Crystals were soaked in 50 μL of 100 mM Tris pH 8.5, 30% PEG 3350, 20 mM sodium vanadate, and 20 mM KDO (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number K2755) for 3 d at room temperature before data collection. Surface solvent was removed by passing the crystal through Paratone and then flash-cooling it in liquid nitrogen. The crystals belonged to the space group I4. Data were collected at a single wavelength (1.54 Å) on a Bruker MICROSTAR micro-focus rotating anode with Helios optics and Platinum 135 CCD detector, using a four-circle kappa goniometer. Data were collected to 1.8 Å resolution, reduced using SAINT and scaled using SADABS from the PROTEUM2 software suite.24

The structure of ligand-bound HI-KDO8PP was determined at 1.8 Å resolution with phases from the molecular replacement method using the program MOLREP in the CCP4 suite. The search model was the protomer of HI-KDO8PP (PDB ID: 1K1E, Chain A with 7 C-terminal residues manually removed),7 leading to a clear solution for a single protomer in the unit cell. The presence of twinning was confirmed by examination of the cumulative intensity distribution, with a twinning fraction of 0.33 and twin law -k, -h, -l. The structure was refined using the program PHENIX with the data between 29.46 and 1.8 Å, for which F ≥ 2σ(F) with alternating cycles of positional and individual temperature-factor refinement. Twin refinement was included in the rounds of refinement, resulting in improved maps compared to those without twin refinement. The resulting model was inspected and modified using the program COOT. In the final stages of refinement, water molecules were added to the model with electron-density acceptance criteria of F ≥ 3σF in the Fo–Fc difference electron-density map. Vanadate and KDO were added to the model in the final round of refinement. A simulated-annealing omit map with coefficients 2Fo–Fc, was calculated by omitting the ligands VO3− and KDO and running one round of simulated annealing refinement in PHENIX (current composite-omit routines cannot account for twinning). Unit cell parameters, data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 2.

The final model consisted of residues 1 – 179 (Gln 180 was disordered). KDO was modeled in the active site but in two different orientations: one in which KDO is coordinated to the VO3− and the other in which the KDO C8-OH forms a hydrogen bond to an oxygen atom of VO3− (Figure SI13).

Structures of KDN9PP and KDO8PP Orthologs

The X-ray crystallographic structures of the KDO8PPs from P. syringae, L. pneumophila, V. cholera, and the KDN9PP from S. avermitilis were also determined. The detailed protocols are reported in Supplemental Information and the specific unit cell parameters, data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table SI1.

Determination of Steady-State Kinetic Constants

The steady-state kinetic constants were measured for BT-KDN9PP (BT1713), BT-KDO8PP (BT1677), Q9KP52 (Vibrio cholerae), Q48EB9 (Pseudomonas syringae), Q5ZX93 (Legionella pneumophila subsp. pneumophila), HI1679 (Haemophilus influenza), P0ABZ4 (Escherichia coli), and Q82HY3 (Streptomyces avermitillis) using the previously published procedure.9, 17

Bioinformatic Analysis

The list of KDN9PP and KDO8PP sequences were identified by first carrying out BLAST25 searches of available bacterial (3,919) and archaeal (250) genomes in NCBI and the Genome database. The KDN9PP sequences were confirmed by the presence of the corresponding synthases or additional biological context in the case of the KDO8PP sequences (see SI, Supplemental Results). Highly redundant sequences were removed (>90%), and the remaining sequences were checked for the presence of a complete set of catalytic residues (for example, BT-KDN9PP Asp10, Asp12, Thr54, Lys80, Asp103 and Asp107) indicating catalytic activity. The resultant sequences were curated and sorted using the specificity markers for KDN9PP (Glu56/Lys67 pair) and KDO8PP (either Arg60 based on HI-KDO8PP numbering or Gly63 based on BT-KDO8PP numbering). The KDN9PP and KDO8PP fusion proteins were parsed into separate groups. The accuracy of the sorting the KDN9PP and KDO8PP sequences was confirmed by examining the co-occurrence of a likely KDN9P synthase or KDO8P synthase gene, respectively. The sequences within the respective groups were aligned using Clustal Omega.26 The phylogenetic tree was generated using ClustalW2 Phylogenetic Tree Tool27 and then exported in Newick format. The tree of life was generated from iTOL (itol.embl.de)28 and downloaded in the Newick format. FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) was used for visualization and figure generation. Sequence logo figures were generated using WebLogo.29

Results and Discussion

Determination of Substrate Preference

We began the investigation of the divergence of structure, substrate recognition, and biological function within the HADSF YbrI clade with the KDO8PP and KDN9PP paralogs from Bacteriodes thetaiotaomicron (BT1677 and BT1713). Ultimately, we also included KDO8PP and KDN9PP homologs from phylogenetically diverse bacteria. KDN9PP and the KDN biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 1) were first discovered in B. thetaiotaomicron.17 BT1713 was found to catalyze the hydrolysis of KDN9P (kcat/Km = 3×104 M−1s−1), N-acetylneuraminate 9-phosphate (Neu5Ac-9P, kcat/Km = 6×103 M−1s−1) and KDO8P (kcat/Km = 2×102 M−1s−1) and yet was found to have little activity towards other phosphate ester metabolites.9 The gene encoding BT1713 was also found to be adjacent to those of a synthase (BT1714) and KDN:CMP transferase (BT1715).17 Gene context combined with substrate specificity analysis led to the identification of BT1713 as BT-KDN9PP. BT1677 was proposed to be BT-KDO8PP, but had not yet been previously characterized. However, the homologous KDO8PP operative in the KDO pathway (Scheme 1) in Haemophilus influenza (HI-KDO8PP)7 and in Escherichia coli (EC-KDO8PP) were known.8 The presence of the KDO pathway in B. thetaiotaomicron was evident from the presence of the complete set of genes associated with the pathway (viz. KDO8P synthase, BT4321; KDO8PP, BT1677; and KDO:CMP transferase BT0725), which are homologous to the genes of the E. coli KDO pathway.

Steady-state kinetic techniques were used to determine the turnover rates (kcat) and the substrate specificity constants (kcat/Km) for the hydrolysis of KDN9P and KDO8P catalyzed by BT1713, BT1677 and the structurally characterized homologs from E. coli (EC)8 and H. influenza (HI).7 In the end, the homologs from S. avermitilis (SA), P. syringae (PS), V. cholera (VC), and L. pneumophila pneumophila str. Philadelphia 1 (LP) were included. These homologs were produced in the early stages of the Enzyme Function Initiative for the purpose of structure-based function determination.

With the exception of BT-KDN9PP and the S. avermitilis homolog, each of the enzymes showed significantly higher kcat and kcat/Km values as catalysts of KDO8P hydrolysis than KDN9P hydrolysis (Table 1). The E. coli homolog displayed the highest level of discrimination with the KDO8P/KDN9P kcat ratio equal to 168 and the kcat/Km ratio equal to 4,500, respectively. The KDO8P/KDN9P kcat ratio reflects the ability of the enzyme to orient the bound substrate in a manner that is optimal for catalytic turnover (viz., productive binding). The kcat/Km ratio on the other hand, reflects both substrate binding affinity and proper orientation. It follows that the active site of the E. coli homolog binds and orients KDO8P much more effectively than it does KDN9P. This specialization is consistent with the biological role of this enzyme as the KDO8PP operative in the E. coli KDO biosynthetic pathway.8

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic constants determined for selected members of the YbrI clade as catalysts of KDN9P or KDO8P hydrolysis in 50 mM K+HEPES containing 2 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.0, 25 °C).

| YbrI clade Phosphatase | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | kcat/Km ratioa | kcat ratioa | Functional Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. thetaiotaomicron | KDO8P | 0.092 ± 0.003 | 430 ± 70 | 2.0 × 102 | 0.018 | 0.077 | KDN9PP |

| BT1713 | KDN9P | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 110 ± 9 | 1.1 × 104 | |||

| S. avermitillis | KDO8P | 0.094 ± 0.003 | 122 ± 8 | 7.7 × 102 | 0.64 | 0.47 | KDN9PP |

| Q82HY3 | KDN9P | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 170 ± 10 | 1.2 × 103 | |||

| B. thetaiotaomicron | KDO8P | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 1.5 × 104 | 217 | 25 | KDO8PP |

| BT1677 | KDN9P | 0.061 ± 0.005 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 6.9 × 101 | |||

| E. coli | KDO8P | 13 ± 1 | 170 ± 20 | 7.7 × 105 | 4,500 | 168 | KDO8PP |

| P0ABZ4 | KDN9P | 0.077 ± 0.004 | 460 ± 90 | 1.7 × 102 | |||

| H. influenza | KDO8P | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 160 ± 20 | 4.8 × 103 | 370 | 37 | KDO8PP |

| HI1679 | KDN9P | 0.021± 0.003 | 1600 ± 500 | 1.3 × 101 | |||

| L. pneumophila | KDO8P | 0.080 ± 0.004 | 46 ± 6 | 1.7 × 103 | 94 | 4.4 | KDO8PP |

| Q52X93 | KDN9P | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 1000 ± 100 | 1.8 × 101 | |||

| P. syringae | KDO8P | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 50 ± 7 | 1.2 × 104 | 670 | 6.7 | KDO8PP |

| Q48EB9 | KDN9P | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 960 ± 40 | 1.8 × 101 | |||

| V. cholerae | KDO8P | 0.089 ± 0.002 | 19 ± 2 | 4.7 × 103 | 200 | 3.6 | KDO8PP |

| Q9KP52 | KDN9P | 0.025 ± 0.001 | 1100 ± 100 | 2.3 × 101 |

The ratio reflects the value of the kinetic constant measured using KDO8P as substrate divided by the value of the kinetic constant measured using KDN9P as substrate.

The KDO8P/KDN9P kcat and kcat/Km ratios measured for BT1677 and the HI, LP, PS, and VC homologs (kcat/Km ratio equal to 217, 370, 94, 670, and 200, respectively and kcat ratio equal to 25, 37, 4.4, 6.7 and 3.6, respectively) indicate a broad range in selectivity. It is also evident from these data that the KDO8P binding affinity is the predominate determinant of selectivity. The kinetic constant ratios are consistent with the findings from bioinformatic analysis (vide infra), as each of these enzymes function in the KDO pathway as indicated by their cooccurrence with the pathway KDO8P synthase. Thus, hereafter each of these homologs will be referred to as a KDO8PP from a particular source (e.g., BT-KDO8PP). BT1713 and the S. avermitilis homolog on the other hand, function in the KDN pathway (vide infra) and are thus named BT-KDN9PP and SA-KDN9PP.

The SA-KDN9PP was engineered as a singleton protein from a two-domain protein comprised of the KDN9PP domain and the KDN:CMP-transferase domain. The comparatively lower kcat/Km values (7.7 × 102 M−1s−1 and 1.2 × 103 M−1s−1 for KDO8P and KDN9P, respectively) observed for SA-KDN9PP might be the consequence of this engineering. Nevertheless, KDN9P is the preferred substrate. The BT-KDN9PP on the other hand, displays a catalytic efficiency towards its physiological substrate that is similar to catalytic efficiencies of the KDO8PP enzymes towards KDO8P. Moreover, BT-KDN9PP prefers KDN9P over KDO8P by a significant factor (KDN9P/KDO8P kcat and kcat/Km ratios of 13 and 56, respectively).

In light of these differences in specificity, we turned to structural information to uncover the binding determinants. The structure of BT-KDN9PP liganded to N-acetylneuraminate (Neu5Ac) is available,9 but not the complex with KDN. The KDO-liganded structure of E. coli KDO8PP has been described16 but due to the resolution there is some ambiguity as to the identity of substrate-binding residues. Although this work is informative, it does not assist in elucidating the basis of specificity and functional divergence or in clearly demarcating these paralogous enzymes. In order to identify differences in active site structure that might account for the observed substrate selectivity, the X-ray crystallographic structures of these KDOPP and KDN9PP orthologs were determined, alone and in complex with transition-state analogs.

X-ray Crystal Structures of Mg2+ and Mg2+/Metavanadate-Sugar Acid Complexes of KDN9PP and KDO8PP

The X-ray crystal structures of KDN9PP and KDO8PP bound to Mg2+ (the cofactor) alone, or to the complex of Mg2+, metavanadate (VO3−) and the corresponding sugar-acid (KDO or KDN), were determined (Figure SI1). Our initial goal was to determine the structures of BT-KDN9PP bound to KDN and with KDO and the structures of BT-KDO8PP bound to KDO and KDN. However, we were only successful in obtaining the structures of the BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDN complex and BT-KDO8PP bound to Mg2+ (Table 2). For representation of the liganded KDO8PP complex we determined the structure of HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO (Table 2), but unfortunately, not the corresponding KDN complex. Finally, the structures of SA-KDN9PP-Ca2+, PS-KDO8PP-Mg2+, VC-KDO8PP-Mg2+ and LP-KDO8PP-Ca2+ were determined (Table SI1).

Comparison of the structures of the BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDN9PP and HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO complexes

A representative dimer (encompassing one active site) from each of the tetrameric structures of liganded BT-KDN9PP and HI-KDO8PP is shown in Figures 2A and 3A, respectively. The Mg+2 and VO3− are coordinated by residues of the catalytic subunit and the KDN and KDO are bound by residues of the cap and catalytic subunits. Figures 2B and 3B highlight the catalytic residues whereas Figures 2C and 3C highlight the KDN and KDO-binding residues, respectively.

Figure 2. Structure of BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+−VO3−-KDN.

(A) Dimer from tetrameric BT-KDN9PP with “catalytic” subunit colored dark blue and “cap” subunit colored light blue, HAD catalytic motifs are shown as dark blue sticks, KDN is shown as yellow sticks, vanadium is colored slate blue and magnesium is a magenta sphere. (B) HAD catalytic residues and (C) KDN binding residues. (B) and (C) are colored as in (A).

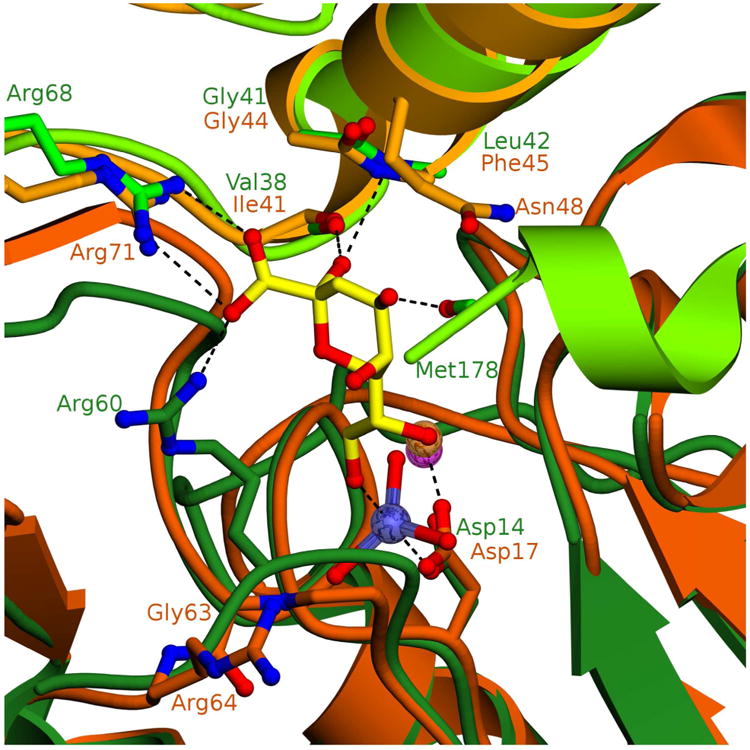

Figure 3. Structure of HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO.

(A) Dimer of HI-KDO8PP (generated from symmetry mates comprising tetramer) with “catalytic” subunit colored forest green and “cap” subunit colored light green, HAD catalytic motifs are shown as forest green sticks, KDN is shown as yellow sticks, vanadium is colored slate blue and magnesium is a magenta sphere. (B) HAD catalytic residues and (C) KDN binding residues. (B) and (C) are colored as in (A).

The BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDN9P and HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO structures (Figures 2B and 3B) provide snapshots which represent the transition-state for the first step of the two-step phosphoryl transfer reaction. In this step the Asp nucleophile attacks the substrate phosphoryl group displacing, with the assistance of the Asp acid, the acid sugar KDN or KDO (Scheme 2). The vanadium assumes a 5-coordinate, trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry, in which the three oxygen atoms from the metavanadate are located in equatorial positions and the Asp nucleophile carboxylate group (BT-KDN9PP Asp10 and HI-KDO8PP Asp14) and the KDN C9-O or KDO C8-O are located at the apical positions, suggestive of backside, in-line displacement of the substrate leaving group during catalytic turnover. The carboxylate groups of the respective Asp acid catalysts (BT-KDN9PP Asp12 and HI-KDO8PP Asp16) are engaged in hydrogen-bond formation with the KDN C9-O or KDO C8-O. The Motif 2 Thr/Ser and Motif 3 Lys (BT-KDN9PP Thr54 and Lys80; HI-KDO8PP Ser58 and Lys84) form hydrogen bonds with the two of equatorial oxygen atoms, and Mg2+ forms a coordination bond to third equatorial oxygen atom. The Mg2+ is also coordinated to the “non-reacting” oxygen atom of the Asp nucleophile carboxylate group, the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of the Asp acid, one of the two oxygen atoms of the metal-binding Motif 4 Asp/Glu residues (BT-KDN9PP Asp103 and HI-KDO8PP Asp107) and two water molecules.

Scheme 2. Chemical pathway catalyzed by the HADSF phosphatase.

The residues that bind the substrate leaving group (KDN or KDO) via hydrogen bond formation (Figures 2C and 3C) are of special interest because they are expected to play important roles in the discrimination between KDN9P and KDO8P. The KDN moiety bound to BT-KDN9PP is anchored by a hydrogen bond with Glu56, which is located on the catalytic subunit and with Arg64, Lys67, and Thr34 located on the cap subunit. A hydrogen-bond network is formed between the Glu56 and the KDN C(7)OH, C(2)OH and the cap subunit Lys67, which in turn forms a hydrogen bond with the KDN C(2)OH. The Arg64 forms two hydrogen bonds with the KDN carboxylate group and Thr34 forms hydrogen bonds with the KDN C(6)O and C(7)OH. The KDN C(4)OH and C(5)OH do not form hydrogen bonds with the enzyme but are instead solvent exposed. The same orientation was observed for the Neu5Ac-9P ligand in the previously reported structure of the BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+-VO3−-Neu5Ac complex (Figure SI2).9

The structure of the HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO complex (Figure 3C) indicates that the KDO moiety of the KDO8P substrate engages in hydrogen-bond formation with cap subunit residues Arg68 (salt bridge between side chain and both oxygen atoms of the KDO carboxylate), Val38 (backbone C=O and KDO C(2)OH), Leu42 (backbone NH and KDO C(2)OH) and Met178 (backbone C=O and KDO C(3)OH), and with the catalytic subunit residue Arg60 (hydrogen bond between side chain and a KDO carboxylate group oxygen atom).

The hydrogen bonds between the KDN moiety and the BT-KDN9PP active-site residues indicate that Glu56, Arg64, Lys67, and Thr34 are key KDN binding residues. Likewise, the hydrogen bonds formed between KDO and the HI-KDO8PP active site residues suggest Arg68 and Arg60 (plus Val38, Leu42 and Met178 which bind via their backbone amide groups) are the key KDO binding residues. To determine if these two sets of residues are conserved in KDN9PP and KDO8PP homologs the X-ray structures of BT-KDN9PP and SA-KDN9PP were compared to the X-rays structures of HI-, PS-, VC- and LP-KDO8PP determined in the present work, and that of the EC-KDO8PP previously reported.16

Comparison of KDN and KDO binding residues among structurally-characterized KDN9PP and KDO8PP enzymes

KDN9PP enzymes

The BT-KDN9PP and SA-KDN9PP originate from evolutionarily distant bacterial species that belong to two separate phyla (Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria, respectively). The BT-KDN9PP is a standalone protein whereas the SA-KDN9PP is one catalytic domain within a two-domain fusion protein that includes the KDN:CMP transferase. BT-KDN9PP and SA-KDN9PP possess 31% sequence identity, and similar tertiary and quaternary structures (Figure SI3). The superposition of the BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDN and SA-KDN9PP-Ca2+ structures (Figure SI4) reveals some degree of divergence in the catalytic site (viz., BT-KDN9PP Thr54 and Asp103 are replaced by Ser62 and Asn110 in SA-KDN9PP) and in the KDN binding site (BT-KDN9PP residue Thr34 is replaced with Arg42). However, the BT-KDN9PP Glu56, Arg64, and Lys67 are conserved in SA-KDN9PP as Glu64, Arg72 and Lys75, respectively. A sequence alignment of the single domain KDN9PP proteins and the KDN9PP-KDN:CMP transferase fusion proteins shows that all three of these binding residues are stringently conserved (vide infra).

KDO8PP enzymes

HI-KDO8PP and BT-KDO8PP also originate from evolutionarily divergent bacterial species (HI belongs to the phylum Proteobacteria). These two orthologs share only 24% sequence identity, yet they have similar tertiary and quaternary structures (Figure SI5). The superposition of the structure of the HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO complex with the structure of the BT-KDO8PP-Mg2+ complex shows that the catalytic residues are largely conserved (BTKDO8PP Asp 17, Asp19, Thr58, Lys87 and Asp110 vs. HI-KDO8PP Asp14, Asp16, Ser58, Lys84 and Asp107) whereas the KDO binding residues are not as well conserved (Figure 4). The HI-KDO8PP cap-subunit residues Val38 and Leu42, correspond to Ile41 and Tyr45 in BT-KDO8PP. However, the positions of the backbone amide groups of BT-KDO8PP Ile41 and Tyr45 are similar to those of the HI-KDO8PP Val38 and Leu42 and therefore, it is likely that the two hydrogen bonds made to the KDO moiety are conserved despite the fact that the amino-acid side chains are not. The counterpart to the HI-KDO8PP cap subunit Arg68 is Arg71 and thus, this salt bridge interaction is retained. In contrast, the hydrogen bond between the HI-KDO8PP catalytic subunit Arg60 side chain and the KDO carboxylate group has no counter-part in BT-KDO8PP (Figure 4). The BT-KDO8PP Gly63 is located at the HI-KDO8PP Arg60 position, and although, Arg64 is next in sequence it is not in position for salt bridge formation with the KDO carboxylate group (Figure 4). In addition, the hydrogen bond to the KDO C(4)OH formed by the HI-KDO8PP cap-domain residue Asn48 (side chain) is altered or lost in BT-KDO8PP because of the replacement of the Asn48 with Lys45 (Figure SI5). Because the C-terminus of BT-KDO8PP could not be modeled in the X-ray crystallographic structure, a seven residue truncation of BT-KDO8PP (BT-KDO8PP Δ167) was generated to ascertain whether the BT-KDO8PP C-terminus plays an analogous role to that of the HI-KDO8PP C-terminus (where there is a hydrogen bond between KDO C(4)OH and the Met178 C=O). BT-KDO8PP Δ167 was found to have a kcat of 0.10 s−1 and kcat/Km of 1.3 × 104 M−1s−1, which is 15 and 115 fold lower than that of full length BT-KDO8PP, indicating the C-terminus of BT-KDO8PP plays a role in catalysis or substrate positioning.

Figure 4. Overlay of HI-KDO8PP and BT-KDO8PP active sites.

Dimer of HI-KDO8PP (generated from symmetry mates comprising tetramer) with “catalytic” subunit colored forest green and “cap” subunit colored light green, KDN is shown as yellow sticks, vanadium is colored slate blue and magnesium is a magenta sphere. Dimer of BT-KDO8PP with “catalytic” subunit colored dark orange and “cap” subunit colored light orange, magnesium is an orange sphere. Putative substrate binding residues are shown as sticks and labeled in their corresponding enzyme color. Hydrogen bonds and coordination bonds are shown as dashed lines.

The superposition of the structures of HI-, BT-, PS-, LP-, EC- and VC-KDO8PP (Figure SI6) shows that VC-KDO8PP and PS-KDO8PP are similar to HI-KDO8PP in that they conserve the position of the catalytic subunit Arg60 as Arg75 and Arg69, respectively. Thus, they are likely to use these residues, along with their respective cap subunit residues Arg83 and Arg77, to bind the KDO carboxylate group. EC-KDO8PP Arg78 (homologous to HI-KDO8PP Arg60), is not correctly oriented for interaction with the KDO carboxylate group in this structure, but due to the flexible nature of the Arg side chain, can be modeled in the productive position. The LP-KDO8PP, on the other hand, is unique in that Ala71 rather than a Gly (Gly63 in BT-KDO8PP) corresponds to the HI-KDO8PP Arg60, and Gln72 corresponds to the BT-KDO8PP Arg64. It is anticipated that neither LP-KDO8PP Ala71 or Gln72 contribute to binding KDO.

Although the overall sequence divergence among these six KDO8PPs is quite high (25 - 58% pair-wise sequence identity; see Table SI2), the backbone fold is highly conserved such that it is likely that the hydrogen bonds formed between the KDO and the HI-KDO8PP backbone Val38 C=O and Leu42 NH have counterparts in the BT, PS, LP, EC and VC-KDO8PP (Figure SI6).

One can observe a distinct classification of KDO sequences by their specificity residues (Arg vs. Gly by analyzing alignment of orthologous sequences (Fig SI7-8). This suggests evolutionary divergence along more than one pathway (vide infra). The only KDO binding residue that is stringently conserved in KDO8PP is the cap subunit Arg (HI-HDO8PP Arg68, BT-KDO8PP Arg71, etc.), which is also stringently conserved among the KDN9PPs (Figure SI9).

KDN vs. KDO Orientation

The superposition of the structures of the BT-KDN9PP-Mg2+ VO3−-KDN and HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO complexes (Figure SI10) indicates that the KDO8PP binds the alpha epimer of KDO, whereas the KDN9PP binds the beta epimer of KDN. . Whereas the respective ring carboxylate groups are similarly positioned to form salt-bridges with the KDO8PP and KDN9PP cap domain Arg side chains, the KDN and KDO C(2)OH groups are oriented toward opposite sides of the respective binding sites. Specifically, the KDN C(2)OH is proximal to the BT-KDN9PP cap subunit Lys67 and catalytic subunit Glu56, with which it forms hydrogen bonds. The KDO C(2)OH on the other hand, is oriented toward the KDO8PP cap subunit (α-helix) backbone Val38 C=O and Leu42 NH with which it forms hydrogen bonds. Given that KDO8P is a slow substrate for BT-KDN9PP, and KDN9P is a slow substrate for KDO8PP, it would be of interest to know if the alternate substrate binds the ring in the same orientation as the natural substrate. However, attempts to obtain the X-ray structures of the corresponding complexes were unsuccessful.

Substrate Specificity and Structure of Glu56Ala and Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala BT-KDN9PP

Common to each of the KDN9PP and KDO8PP enzymes examined is the potential for salt bridge formation between the KDO or KDN carboxylate group and the cap subunit Arg residue (BT-KDN9PP Arg64, HI-KDO8PP Arg68, etc.). Ala replacement of this Arg in BT-KDN9PP removes all detectable activity.9 Sequence alignments (Figures SI7-9) indicate that this Arg residue is invariant. Therefore, the Arg is considered to be a key substrate-binding residue in both KDN9PP and KDO8PP. Each of the KDO8PPs tested (Table 1) show catalytic activity with KDN9P that is significantly less than that observed with KDO8P. A Glu-Lys pair (BT-KDN9PP Glu56-Lys67) formed by a Glu that originates from the catalytic subunit and a Lys from the cap subunit appear to play a key role in the divergence of KD9PP function. These Glu and Lys residues make hydrogen bonds with the KDN C(2)OH and the Lys also forms a salt bridge with the KDN carboxylate residue. In BT-KDO8PP, the corresponding residues are Gly63 and Ala74.

If the BT-KDN9PP Glu56-Lys67 residues were replaced with Ala residues would the substrate selectivity change? To address this question the BT-KDN9PP Glu56Ala variant was prepared as was the Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala variant (the Lys67Ala variant proved to be insoluble). The X-ray crystallographic structures of Glu56Ala and Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala BT-KDN9PP proteins were determined (Table SI3) to verify retention of the native fold. Neither structure differs significantly from that of wild-type BT-KDN9PP, with RMSD values of 0.2 Å and 0.3 Å for the Glu56Ala and Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala variants, respectively. Except for the mutation site, the active sites were unchanged (Figure SI11).

The steady-state kinetic constants were measured for the single and double mutant for catalysis of KDN9P or KDO8P hydrolysis (Table 3). Compared to wild-type, with KDN9P serving as substrate, the Glu56Ala mutant displayed a 46-fold decrease in kcat and a 180-fold decrease in kcat/Km whereas the Glu56Ala/Lys67Ala mutant displayed a 300-fold decrease in kcat and a 2700-fold decrease in kcat/Km. Thus, both residues make a significant contribution to substrate-binding affinity and orientation. In contrast, with KDO8P serving as substrate the kcat and kcat/Km values are essentially unchanged by the mutations. These results suggest that when bound to the KDN9PP active site, KDO8P does not engage in hydrogen bond formation with the Glu56-Lys67 pair. Indeed, if KDO8P were to bind to KDN9PP in the same ring orientation as that observed for KDO in the HI-KDO8PP-Mg2+-VO3−-KDO structure (vide supra), hydrogen bond formation between the KDO C(2)OH and the Glu56-Lys67 pair would not be possible.

Table 3.

Comparison of wild-type and mutant BT-KDN9PP and BT-KDO8PP steady-state kinetic constants measure for the catalyzed hydrolysis of KDN9P or KDO8P in 50 mM K+HEPES containing 2 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.0, 25 °C).

| Enzyme | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | kcat/Km ratioa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT-KDO8PP WT |

KDO8P | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 1.5 × 104 | 217 |

| KDN9P | 0.061 ± 0.005 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 69 | ||

|

| |||||

| BT-KDO8PP Δ167 |

KDO8P | 0.10 ± 0.1 | 0.76 ± 0.01 | 1.3 × 102 | |

|

| |||||

| BT-KDN9PP WT |

KDO8P | 0.092 ± 0.003 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 2 × 102 | 0.018 |

|

| |||||

| KDN9P | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.105 ± 0.009 | 1.1 × 104 | ||

|

|

|||||

| BT-KDN9PP E56A |

KDO8P | 0.109 ± 0.02 | 0.207 ± 0.09 | 5 × 102 | 8.3 |

|

| |||||

| KDN9P | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 6 × 101 | ||

|

|

|||||

| BT-KDN9PP E56A/K67A |

KDO8P | 0.062 ± 0.002 | 0.196 ± 0.009 | 3.1 × 102 | 75 |

|

| |||||

| KDN9P | 0.004 ± 0.0008 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 4.1 | ||

The ratio reflects the value of the kinetic constant measured using KDO8P as substrate divided by the value of the kinetic constant measured using KDN9P as substrate

Bioinformatic Analysis of KDO8PP and KDN9PP Evolution

A bioinformatic study of KDO8PP and KDN9PP was carried out, in which the genes encoding the KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs in all available bacterial (3,919) and archaeal (250) genomes in the NCBI public data bank were identified, and the encoded protein sequences were analyzed within the context of multiple sequence alignments (see Materials and Methods for details). The purpose of this analysis was three-fold: (1) to define the variation in the identities of the key active-site residues revealed by the X-ray crystallographic structures, (2) to examine the evolutionary distance between the orthologs and (3) to map the biological ranges of the KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs within the boundaries set by the sequence represented in NCBI.

Identification of separate categories of KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs and analysis of their distribution

Of the total 1380 non-redundant ortholog sequences identified, 1246 were found to be KDO8PPs and 134 were found to be KDN9PPs (46 KDN9PP genes and 88 genes encoding a fusion protein comprised by a KDN9PP domain and a KDN:CMP transferase domain, Table 4). The cap subunit substrate-binding Arg residue (BT-KDN9PP Arg64, HI-KDO8PP Arg68 and BT-KDO8PP Arg71; Figures 2C, 3C and 4) is present in all sequences. The alignment of the 987 KDO8PP orthologs (Table 4) that are distinguished by the KDO8P-binding Arg located at the catalytic subunit (HI-KDO8PP Arg60; Figure 3C) is represented by the sequence logo shown in Figure SI7. There is a group of KDO8PP ortholog sequences found in Fusobacteria (26 total), in which this residue is replaced by a Lys (see Table 4 and in the sequence logo shown in Figure SI7). It is assumed that the Lys side chain can substitute for the Arg side chain in salt-bridge formation with the KDO carboxylate group. The alignment of the 259 KDO8PP sequences that possesses a Gly (or in a smaller number of sequences, Ala) (BT-KDO8PP Gly63; Figure 4) in place of Arg, is represented by the sequence logo shown in Figure SI8. The Spirochaetes phyla contains 16 KDO8PP sequences with Asn (8 total) or Ser (8 total) in place of the Arg residue; these have been excluded from sequence logo figures. The alignment of the KDN9PP ortholog sequences (represented by the sequence logo of Figure SI9) illustrates the conserved (catalytic subunit) Glu-Lys (cap subunit) KDN9P-specific binding motif (BT-KDN9PP Glu56-Lys67; Figure 2C).

Table 4.

Summary of the bioinformatic results. Column 1 lists the taxonomic rank of the source of the KDN9PP and/or KDO8PP encoding genes, column 2 lists the number of genes found within that source and column 3 and 4 specify the distribution according to assigned protein identity (see text for details).

| Source | Genes Identified | KDO8PP | KDN9PP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaea | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 1 fusion | |||

| Acidobacteria | 11 | 7 Arg | 3 |

| 1 Gly | |||

| Actinobacteria | 51 | 0 | 51 fusion |

| Aquificae | 10 | 10 Arg | 0 |

| Bacteroides | 244 | 10 Arg | 18 |

| 200 Gly | 16 fusion | ||

| Chlorobi | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Chloroflexi | 1 | 1 fusion | |

| Chrysiogenetes | 1 | 1Arg | 0 |

| Cyanobacteria | 15 | 1 Arg | 0 |

| 14 Gly | |||

| Deferibacteres | 4 | 4 Arg | 0 |

| Elusomicrobia | 2 | 1 Arg | 0 |

| 1 Gly | |||

| Firmicutes / Bacilli | 4 | 4 Arg | 0 |

| Firmicutes / Clostridia | 26 | 18 Arg, 1 Arg fusion | 7 fusion |

| Firmicutes / Negativicutes | 47 | 46 Arg | 1 |

| Fusobacteria | 28 | 26 Lysa | 0 |

| 2 Alab | |||

| Gemmatimonadetes | 1 | 1Arg | 0 |

| Lentisphaera | 1 | 1 Arg | 0 |

| Proteobacteria / Alpha | 7 | 1 Arg | 2 |

| 4 fusion | |||

| Proteobacteria / Beta | 189 | 182 Arg, 6 Arg fusion | 1 fusion |

| Proteobacteria / Delta | 48 | 36 Arg, 3 Arg fusion | 1 |

| 6 Gly | 2 fusion | ||

| Proteobacteria / Epsilon | 59 | 54Arg | 4 |

| 1 fusion | |||

| Proteobacteria / Gamma | 556 | 529 Arg, 8 Arg fusion | 0 |

| 19 Gly | |||

| Proteobacteria / Zeta | 1 | 1 Arg | 0 |

| Nitrospirae | 6 | 4 Arg, 1 Arg fusion | 1 |

| Planctomycetes | 13 | 12 Arg | 1 fusion |

| Spirochaetes | 18 | 8 Serc, 8 Asnd | 2 fusion |

| Synergistetes | 11 | 11 Arg | 0 |

| Thermodesulfobacteria | 3 | 3 Arg | 0 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 6 | 5 Arg | 1 |

Lys replaces the catalytic subunit Arg specificity residue (HI-KDO8PP Arg60).

Ala replaces the catalytic subunit Gly of the KDO8PP-Gly lineage (BT-KDO8PP Gly63).

Ser replaces the catalytic subunit Gly of the KDO8PP-Arg lineage (HI-KDO8PP Arg60).

Asn replaces the catalytic subunit Gly of the KDO8PP-Arg lineage (HI-KDO8PP Arg60).

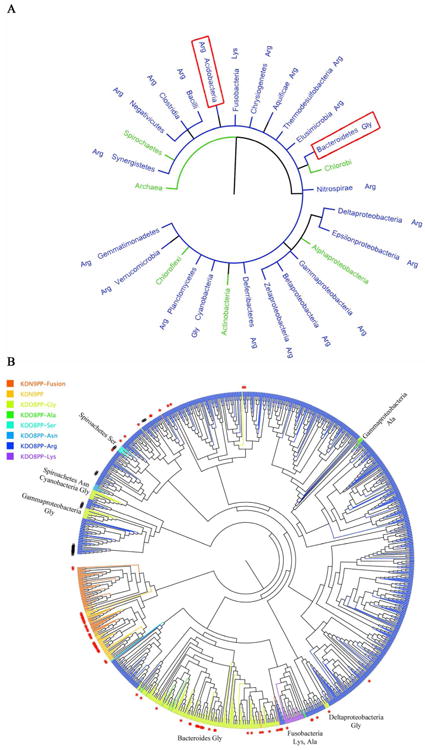

A quantitative analysis of sequences that comprise the different “categories” of KDO8PP (KDO8PP-Arg (fusion vs. singleton), KDO8PP-Lys, KDO8PP-Ser, KDO8PP-Asn and KDO8PP-Gly/Ala) and KDN9PP (fusion vs. singleton) orthologs among the various phyla or divisions is reported in Table 4. Figure 5A provides a schematic of the distribution of KDN9PP and KDO8PP orthologs among bacterial phyla in the form of a 16S ribosomal RNA-rooted phylogenetic tree. A detailed description of biological distribution of the KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs in relation to the occurrence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesis is provided in Supporting Information.

Figure 5.

Schematics of Bioinformatic Analyses. (A) The tree of life generated from iTOL (itol.embl.de), displaying phyla (and class in the case of proteobacteria) that contain KDO8PP and KDN9PP sequences. Phyla are color-coded (KDO8PP blue, KDN9PP green) based on the majority presence of enzymes. Red boxes indicate the two phyla that contain species with both KDN9PP and KDO8PP. The type of KDO8PP enzyme (Arg, Lys, or Gly) is indicated next to the phyla name. (B) An unrooted phylogenetic tree generated using a multiple sequence alignment of all KDO8PP and KDN9PP enzymes identified herein. KDO8PP-Arg enzymes are colored blue, KDO8PP-Gly green, KDN9PP light orange and KDN9PP-KDN:CMP transferase fusions deep orange. Red stars indicate enzymes that were identified where an additional KDN9PP or KDO8PP gene exists within the species. Black number signs (#) indicate KDO8PP-Arg-KDO:CMP transferase fusion genes. The phyla of some KDO8PP-Gly enzymes have been labeled. Figure generated with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

The occurrence of the KDO8PP orthologs is directly coupled with the occurrence of LPS (such as lipid A of Proteobacteria) in which KDO is a common component. LPSs function at the outer membrane surface of diderm (gram-negative) bacteria. Diderms comprise the majority of bacterial phyla.30 The number of KDN9PP orthologs is comparatively smaller than the number of KDO8PP orthologs, which suggests that KDN is used for a more specialized biological function than that of the KDO-containing LPS.

Whereas KDO8PP orthologs are broadly distributed among diderms but not monoderms (gram-positive bacteria), KDN9PP orthologs are selectively distributed among both. For example, KDO8PP orthologs were not found in Archaea, Chlorobi (diderm) and Acintobacteria (monoderm) whereas 3, 14, and 51 KDN9PP orthologs were found, respectively. In contrast, we found 845 KDO8PP orthologs in Proteobacteria as compared to 15 KDN9PP orthologs. Likewise, 28 KDO8PP orthologs were found in Fusobacteria and 15 in Cyanobacteria whereas no KD9PP orthologs were found. In Bacteroides (the closest relative of Chlorobi), 34 KDN9PP orthologs were detected compared to 210 KDO8PP orthologs.

The biological function of KDN appears to be host-dependent. Actinobacteria is a monoderm whose cytoplasmic membrane is elaborated with anionic cell-wall polymers (Teichuronic acid) containing KDN.31-35 On the other hand, certain symbiotic Bacteroides species are thought to use KDN in capsular polysaccharides that are displayed on the outer membrane for the purpose of host mimicry.17, 36

Notably, there were several examples of bacteria wherein a KDN9PP ortholog appears to substitute for a bona fide KDO8PP ortholog in KDO synthesis. Specifically, the Chlorobi phyla includes diderms having outer membrane LPS that contains KDO.37 The bioinformatic analysis identified 12 KDN9PP orthologs, as well as 13 KDO8PP-Arg orthologs. The 13 KDO8PP-Arg orthologs lack the essential Asp nucleophile and are thus assumed to be catalytically inert. Therefore, in these species the KD9PP orthologs must be functioning in the KDO pathway. Also we found 4 species within epsilonproteobacteria that possess KDN9PP orthologs (Helicobacter bizzozeronii CCUG 35545, Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII, Helicobacter felis ATCC 49179, and Helicobacter heilmannii ASB1.4). These species do not possess a KDO8PP gene but do possess both KDN9P and KDO8P synthase genes. Lastly, we note that whereas KDO is present in the LPS38-40 of alphaproteobacteria, only one of the seven genes identified in these organisms encode a KDO8PP ortholog and the remaining genes encode a KDN9PP ortholog.

Evolutionary distance between KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs

The evolutionary distance between the different categories of KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs is represented in Figure 5B in the form of an unrooted phylogenetic tree generated using the alignment of all KDO8PP and KDN9PP sequences identified herein. Because the sequences that comprise the KDO8PP-Arg category greatly outnumber the rest, the tree appears to be rooted in KDO8PP-Arg; no significance is attributed to this point. Rather, we focus on the pattern observed in the grouping of the sequences from the different categories, because this indicates the structural relatedness between these sequences, which in turn reflects shared vs. independent paths in evolution.

From inspection of Figure 5B it is clear that the KDN9PP sequences (light orange) and the KDN9PP-KDN:CMP transferase fusion protein sequences (deep orange) group together and separate from the KDO8PP sequences (dark blue, cyan and green). The conservation of the Lys-Glu substrate specificity motif among all KDN9PP and KDN9PP-KDN:CMP transferase fusion protein sequences indicates a single lineage for the bacterial KDN pathway phosphatase, which has spread across phyla in a rather species-selective manner.

It is also evident from examination of Figure 5B that two major lineages of KDO8PP orthologs have evolved, one with the catalytic subunit Arg functioning as the substrate specificity residue, and the other distinguished by the replacement of this Arg by Gly, as the two categories of sequences group separately. The KDO8PP orthologs from Fusobacteria, which possess Lys (26 sequences) and Ala (2 sequences) at the specificity position, group with the KDO8PP-Arg category sequences. The KDO8PP-Gly lineage is concentrated in Bacteroides (200 KDO8PP-Gly orthologs vs. 10 KDO8PP-Arg orthologs) whereas the KDO8PP-Arg lineage is concentrated in Proteobacteria (820 KDO8PP-Arg orthologs vs 25 KDO8PP-Gly orthologs). Lastly, we note that the KDO8PP-CMP:KDO fusion proteins (indicated with a black # symbol in Figure 5B) were specifically formed from KDO8PP-Arg orthologs.

The few KDO8PP-Arg orthologs that appear in Bacteroides are more closely related in sequence to the Proteobacteria KDO8PP-Arg orthologs than they are to the Bacteroides KDO8PP-Gly orthologs, suggestive of horizontal gene transfer. In contrast, the KDO8PP-Gly orthologs that are found outside of Bacteroides (e.g., in gammaproteobacteria and Cyanobacteria) are more closely related in sequence to the KDO8PP-Arg orthologs than they are to the Bacteroides KDO8PP-Gly orthologs. In addition, Spiroachetes contains KDO8PP-Asn and Ser orthologs that cluster with KDO8PP-Arg orthologs, both indicating there is some relaxation in the selection pressure to maintain Arg at the specificity position.

Conclusions

The KDO8PP orthologs are the products of specialization within the C0 class of HADSF phosphatases, which are involved in the incorporation of a sequence insert to serve as an oligomerization motif for tetramer formation. The interfaced subunits provide the catalytic scaffold and the substrate binding residues in a division of tasks. The vast majority of HADSF phosphatases belong to the C1 or C2 class and thus employ a cap-domain insertion in the Rossmann fold catalytic scaffold to function in substrate selection. The C0 HADSF phosphatases were the first to evolve,4 and now they comprise a comparatively small class of this superfamily.

KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs display phosphatase activity towards both substrates, although a significantly greater activity was observed with the physiological substrate. We attribute the substrate promiscuity to a stringently conserved cap subunit Arg residue, which forms a salt bridge with the carboxylate substituent common to both substrates. The X-ray crystallographic structural data indicate that KDN9PP and KDO8PP bind different epimers of their physiological substrates. The KDN9PP orthologs conserve a Glu-Lys motif that functions in KDN9P binding via the carboxylate and C(2)OH groups. Removal of this motif in BT-KDN9PP by replacement with Ala greatly diminished activity towards KDN9P but not KDO8P. Thus, the Glu-Lys motif, absent in the KDO8PP orthologs, seems to be the product of selection for enhanced activity towards KDN9P and the branch point for the KDN9PP lineage from that of the KDO8PP. The retention of significant KDN9PP activity towards KDO8P provides the opportunity for substitution of KDN9PP for KDO8PP as the phosphatase of the KDO pathway.

The KDO8PP orthologs augment the salt bridge between the cap subunit Arg and the KDO9P carboxylate group with hydrogen bonds formed between three backbone amide groups and the substrate ring hydroxyl substituents. The largest lineage of KDO8PP orthologs (KDO8PP-Arg) employ an Arg residue on the catalytic subunit to form a second salt bridge to the substrate carboxylate group. The other lineage, KDO8PP-Gly evolved separately and does not include the catalytic subunit Arg, but rather a Gly or in some instances Ala is located at the Arg position. Within specific phyla or genera of bacteria, variants of the KDO8PP-Arg lineage are found which have undergone what we speculate to be subsequent conservative amino-acid replacement at the Arg site (viz. Lys in Fusobacteria) or non-conservative amino-acid replacement (viz. Gly in cyanobacteria or Ser in Spirochaetes). Taken together, the KDO8PP and KDN9PP orthologs of the class C0 YrbI clade display diversity in substrate recognition elements which underlie a range of substrate promiscuity and in turn changeability in biological function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all NYSGXRC personnel who contributed to the structure determination. The Center for Synchrotron Biosciences, where diffraction data were collected, was supported by grant P30-EB-009998 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). Use of the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health U54 GM093342 (to K. N. A., D. D.-M., and SCA). The NYSGXRC was supported by NIH Grant U GM074945 (Principal Investigator: S.K. Burley).

Abbreviations

- BT

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron

- EC

Escherichia coli

- HADSF

Haloalkanoate dehalogenase superfamily

- HI

Haemophilus influenzae

- LP

Legionella pneumophila

- KDO

2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate

- KDO8P

2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate

- KDO8PP

2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate-8-phosphate phosphatase

- KDN

2-keto-3-deoxynononate

- KDN9P

2-keto-3-deoxynononate 9-phosphate

- KDN9PP

2-keto-3-deoxynononate-9-phosphate phosphatase

- LPS

lipopolyscaccharide

- Neu5Ac

N-acetylneuraminate

- Neu5Ac-9P

N-acetylneuraminate 9-phosphate

- PS

Pseudomonas syringae

- SA

Streptomyces avermitilis

- VC

Vibrio cholera

Footnotes

The coordinates of E56A, E56A/K67A, and KDNPP complexed with 2-keto-3- deoxynononate and metavanadate from B. thetaiotaomicron, KDO8PP from B. thetaiotaomicron, and KDO8PP complexed with 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate and metavanadate from H. influenzae have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 4HGQ, 4HGR, 4HGO, 4HGN and 4HGP.The coordinates of phosphatase orthologs from S. avermittillis P. syringae, V. cholera, and L. pneumophila, have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3MMZ, 3MN1, 3N07, and 3N1U, respectively.

Supporting Information: Supporting Methods and bioinformatics analysis, as well as Tables S1 – S3 and Figures S1 – S13. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

References

- 1.Nguyen HH, Wang L, Huang H, Peisach E, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Structural determinants of substrate recognition in the HAD superfamily member D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase (GmhB) Biochemistry. 2010;49:1082–1092. doi: 10.1021/bi902019q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang H, Patskovsky Y, Toro R, Farelli JD, Pandya C, Almo SC, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Divergence of structure and function in the haloacid dehalogenase enzyme superfamily: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron BT2127 is an inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8937–8949. doi: 10.1021/bi201181q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rangarajan ES, Proteau A, Wagner J, Hung MN, Matte A, Cygler M. Structural snapshots of Escherichia coli histidinol phosphate phosphatase along the reaction pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37930–37941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burroughs AM, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of the HAD superfamily: understanding the structural adaptations and catalytic diversity in a superfamily of phosphoesterases and allied enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:1003–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Markers of fitness in a successful enzyme superfamily. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selengut JD. MDP-1 is a new and distinct member of the haloacid dehalogenase family of aspartate-dependent phosphohydrolases. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12704–12711. doi: 10.1021/bi011405e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons JF, Lim K, Tempczyk A, Krajewski W, Eisenstein E, Herzberg O. From structure to function: YrbI from Haemophilus influenzae (HI1679) is a phosphatase. Proteins. 2002;46:393–404. doi: 10.1002/prot.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu J, Woodard RW. Escherichia coli YrbI is 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18117–8123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Z, Wang L, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Structure-function analysis of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate phosphatase defines specificity elements in type C0 haloalkanoate dehalogenase family members. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1224–1233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onishi HR, Pelak BA, Gerckens LS, Silver LL, Kahan FM, Chen MH, Patchett AA, Galloway SM, Hyland SA, Anderson MS, Raetz CR. Antibacterial agents that inhibit lipid A biosynthesis. Science. 1996;274:980–982. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strohmaier H, Remler P, Renner W, Hogenauer G. Expression of genes kdsA and kdsB involved in 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid metabolism and biosynthesis of enterobacterial lipopolysaccharide is growth phase regulated primarily at the transcriptional level in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4488–4500. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4488-4500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belunis CJ, Clementz T, Carty SM, Raetz CR. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis and cell growth following inactivation of the kdtA gene in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27646–27652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cipolla L, Polissi A, Airoldi C, Galliani P, Sperandeo P, Nicotra F. The Kdo biosynthetic pathway toward OM biogenesis as target in antibacterial drug design and development. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2009;6:19–33. doi: 10.2174/157016309787581093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cipolla L, Polissi A, Airoldi C, Gabrielli L, Merlo S, Nicotra F. New targets for antibacterial design: Kdo biosynthesis and LPS machinery transport to the cell surface. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:830–852. doi: 10.2174/092986711794927676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue S, Kitajima K, Inoue Y. Identification of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero--galactonononic acid (KDN, deaminoneuraminic acid) residues in mammalian tissues and human lung carcinoma cells. Chemical evidence of the occurrence of KDN glycoconjugates in mammals. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24341–24344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas T, Yi L, Aggarwal P, Wu J, Rubin JR, Stuckey JA, Woodard RW, Tsodikov OV. The tail of KdsC: conformational changes control the activity of a haloacid dehalogenase superfamily phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30594–30603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Lu Z, Allen KN, Mariano PS, Dunaway-Mariano D. Human symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron synthesizes 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D- galacto-nononic acid (KDN) Chem Biol. 2008;15:893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods in Enzymology. New York: 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode; pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winn MD. An overview of the CCP4 project in protein crystallography: an example of a collaborative project. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2003;10:23–25. doi: 10.1107/s0909049502017235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PROTEUM2, Version 2.4. Bruker AXS Inc.; Madison, Wisconsin, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W20–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W475–478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutcliffe IC. A phylum level perspective on bacterial cell envelope architecture. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shashkov AS, Tul'skaya EM, Evtushenko LI, Denisenko VA, Ivanyuk VG, Stomakhin AA, Naumova IB, Stackebrandt E. Cell wall anionic polymers of Streptomyces sp. MB-8, the causative agent of potato scab. Carbohydr Res. 2002;337:2255–2261. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(02)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shashkov AS, Kosmachevskaya LN, Streshinskaya GM, Evtushenko LI, Bueva OV, Denisenko VA, Naumova IB, Stackebrandt E. A polymer with a backbone of 3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galacto-non-2-ulopyranosonic acid, a teichuronic acid, and a beta-glucosylated ribitol teichoic acid in the cell wall of plant pathogenic Streptomyces sp. VKM Ac-2124. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:6020–6025. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tul'skaia EM, Shashkov AS, Bueva OV, Evtushenko LI. Anionic carbohydrate-containing cell wall polymers of Streptomyces melanosporofaciens and related species. Mikrobiologiia. 2007;76:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naumova IB, Shashkov AS. Anionic polymers in cell walls of gram-positive bacteria. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1997;62:809–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tul'skaya EM, Shashkov AS, Streshinskaya GM, Senchenkova SN, Potekhina NV, Kozlova YI, Evtushenko LI. Teichuronic and teichulosonic acids of actinomycetes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2011;76:736–744. doi: 10.1134/S0006297911070030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Mahowald MA, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Martens EC, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Minx P, Latreille P, Cordum H, Van Brunt A, Kim K, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, Clifton SW, Wilson RK, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Evolution of symbiotic bacteria in the distal human intestine. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meißner J, Fischer U, Weckesser J. The lipopolysaccharide of the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium vibrioforme f. thiosulfatophilum. Archives of Microbiology. 1987;149:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsberg LS, Bhat UR, Carlson RW. Structural characterization of the O-antigenic polysaccharide of the lipopolysaccharide from Rhizobium etli strain CE3. A unique O-acetylated glycan of discrete size, containing 3-O-methyl-6-deoxy-L-talose and 2,3,4-tri-O-, methyl-l fucose. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18851–18863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. The structures of the lipopolysaccharides from Rhizobium etli strains CE358 and CE359. The complete structure of the core region of R. etli lipopolysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2747–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. Structural characterization of the primary O-antigenic polysaccharide of the Rhizobium leguminosarum 3841 lipopolysaccharide and identification of a new 3-acetimidoylamino-3-deoxyhexuronic acid glycosyl component: a unique O-methylated glycan of uniform size, containing 6-deoxy-3-O-methyl-D-talose, n-acetylquinovosamine, and rhizoaminuronic acid (3-acetimidoylamino-3-deoxy-D-gluco-hexuronic acid) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16037–16050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709615200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraulis P. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: a program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.