Abstract

Objective

There are effective treatments of trichotillomania (TTM), but access to expert providers is limited. This study tested a stepped care model aimed at improving access.

Method

Participants were 60 (95% women, 75% Caucasian, 2% Hispanic) adults (M = 33.18 years) with TTM. They were randomly assigned to Immediate vs. Waitlist (WL) conditions for Step 1 (10 weeks of web-based self-help via StopPulling.com). After Step 1, participants chose whether to engage in Step 2 (8 sessions of in-person Habit Reversal Training).

Results

In Step 1 the Immediate condition had a small (d = .21) but significant advantage, relative to WL, in reducing TTM symptom ratings by interviewers (masked to experimental condition but not to assessment point); there were no differences in self-reported TTM symptoms, alopecia, functional impairment, or quality of life. Step 1 was more effective for those who used the site more often. Stepped care was highly acceptable: motivation did not decrease during Step 1; treatment satisfaction was high, and 76% enrolled in Step 2. More symptomatic patients self-selected into HRT, and on average they improved significantly. Over one-third (36%) made clinically significant improvement in self-reported TTM symptoms. Considering the entire stepped care program, participants significantly reduced symptoms, alopecia, and impairment, and increased quality of life. For quality of life and symptom severity, there was some relapse by 3-month follow-up.

Conclusions

Stepped care is acceptable, and HRT was associated with improvement. Further work is needed to determine which patients with TTM can benefit from self-help and how to reduce relapse.

Keywords: trichotillomania, stepped care, habit reversal training, web-based self-help, acceptability

Trichotillomania (TTM) involves recurrent pulling out of one’s own hair, resulting in hair loss. TTM shows a one-year prevalence of 1 to 2% (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and can result in psychosocial impairment and stigma (Ricketts, Brandt, & Woods, 2012). A meta-analytic review concluded that habit reversal training (HRT; Azrin & Nunn, 1973) is the best-supported TTM treatment (Bloch, Weisenberger, Domrowski, Nudel, & Coric, 2007). Unfortunately, few clinicians receive adequate TTM training. In a survey of hair pullers, only 3% perceived their providers as TTM experts (Woods et al., 2006). Access to effective treatment might be improved by using stepped care, in which less intensive, restrictive, or costly methods are tried first, followed by more intensive ones only if initial results are unsatisfactory. If successful, stepped care reserves a costly and scarce resource for patients who need it.

Our research addressed four questions about a two-step model of care for TTM: (1) web-based self-help; (2) in-person HRT. First, is web-based self-help for TTM efficacious? Patients can access the Internet from anywhere, regardless of proximity to an expert therapist. An uncontrolled study of a TTM self-help site, StopPulling.com, showed reduced symptoms (Mouton-Odum, Keuthen, Wagener, Stanley, & Debakey, 2006), but there are no published controlled trials. Second, is stepped care for TTM acceptable to patients? We studied acceptability in terms of treatment satisfaction, Step 2 entry and completion, and whether motivation declined if Step 1 failed to help. Third, are those who self-select to enter Step 2 the ones who need it, and do they benefit? Stepped care logic requires that later steps are reserved for those who need them, and that at least some patients find later step(s) useful, or the program will be inefficient. Finally, we examined maintenance of gains through 3-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

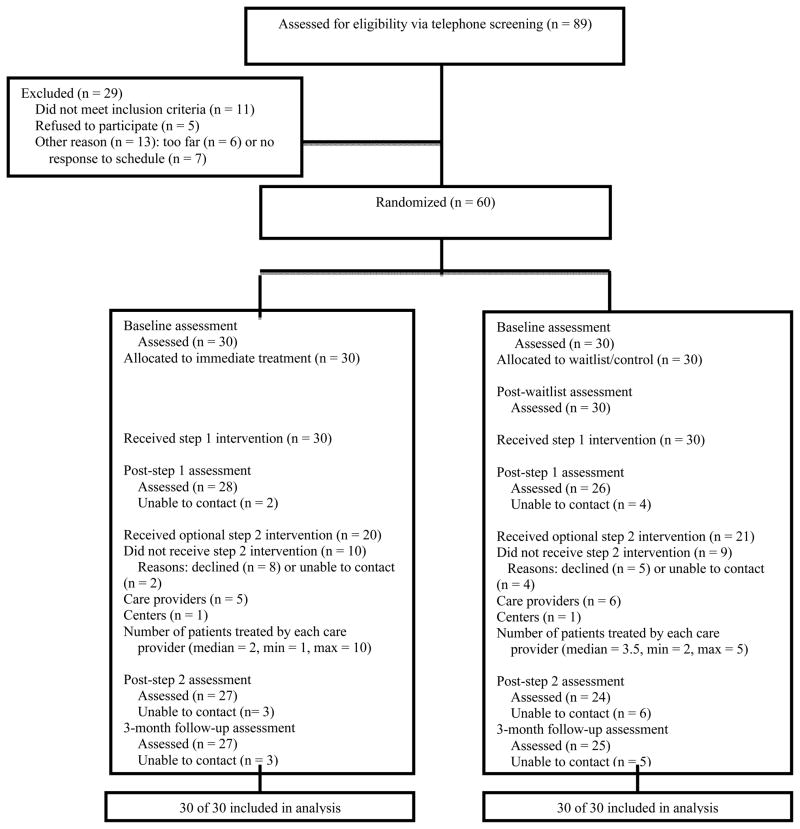

Participants were 60 adults with TTM (57 female), averaging 33.18 years old (SD = 10.87). The majority were Caucasian (75%), with 17% African American. One (2%) was Hispanic. They began hair pulling at a mean age of 11.45 (SD = 4.67). They were recruited September 2010 through November 2011 via ads and clinician referrals. Figure 1 is the CONSORT diagram of patient flow. Inclusion criteria were: >= 18 years old, regular Internet access, and DSM-IV-TR criteria for TTM except that criteria B (tension before pulling) and C (pleasure, relief, or gratification after pulling) were not required (Lochner et al., 2011). Exclusion criteria were (a) those for ordinary use of StopPulling.com (i.e., any past-month suicidality, major depressive episode, psychosis, severe anxiety, or substance abuse); (b) concurrent psychotherapy for TTM; or (c) taking TTM medication but not on stable dose for >= four weeks.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flowchart

Materials

Diagnoses

Interviewers were graduate students trained and supervised by the last author. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) was used for exclusion criteria. TTM was diagnosed with the Trichotillomania Diagnostic Interview (TDI; Rothbaum & Ninan, 2004). TDI (and PITS—see below) interviewers were made aware of the assessment time period (e.g., post-Step 1) so that they could ask about treatment utilization, but not made aware of experimental condition. A 20% random sample of TDIs was coded by a second rater (masked to time and condition), with high agreement (κ =.77).

TTM symptoms

The Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale (MGH-HPS; Keuthen et al., 1995) is a 7-item self-report measure of past-week TTM symptoms (total 0 to 28). In our sample, alpha was .74. Using internal consistency as the reliability estimate, we required a decrease of at least six points on the MGH-HPS for reliable change, a score of 9 or lower for return to normal functioning [> 2 SD below dysfunctional population mean (estimated as our baseline mean)], and both for clinical significance (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). The Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale (PITS; Winchel et al., 1992) is a 6-item, semi-structured interview (total 0 to 42). A 20% random sample of PITS interviews was coded by a second rater (masked to time and condition). Single-rater reliability was high (r = .95, no significant difference in means). The Alopecia rating (Tolin, Franklin, Diefenbach, & Gross, 2002) is a one-item (1 to 7) evaluation of hair loss evident in a photo of the most affected site. Two coders (masked to time and condition) rated each photo; their average rating was reliable (ICC = .82).

Motivation and treatment satisfaction

The Client Motivation for Therapy Scale (CMOTS; Pelletier, Tuson, & Haddad, 1997) is a 24-item questionnaire. We analyzed subscales consisting of four 1–7 items measuring intrinsic motivation, external regulation, and the sum of the two. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Larsen, Attkisson, Hargreaves, & Nguyen, 1979) is an 8-item measure of satisfaction with health services (total scores 8—32).

Impairment and quality of life

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Sheehan, 1983) is a 3-item self-report of impairment in work/school, social life, and home/family life (total 0 – 30). The World Health Organization Quality of Life—Brief Version (WHOQOL Group, 1998) is a 26-item quality of life measure (past two weeks). We used the average (4—20) across four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment.

Treatment adherence

Step 1 adherence was measured objectively as the number of days (0–70) on which a participant entered data on StopPulling.com. The therapist rated Step 2 homework after each session from 0 (“not done”) to 3 (“fully or almost fully completed and documented”). HRT therapist adherence was scored on a 57-item checklist. Two raters watched all sessions of five randomly selected patients; rater reliability was high (κ = .78).

Procedure

Screening, randomization, and assessments

The study was approved by the American University Institutional Review Board. Figure 1 summarizes participants’ progress through the study. Prospective participants completed a phone screen. Those who were interested and likely to be eligible were scheduled for baseline assessment. All in-person assessments were conducted in the PI’s lab at American University. At baseline, after informed consent, interviews were conducted, followed by all self-reports (except the CSQ-8) and the photo for alopecia rating. Finally, those who were eligible and interested were randomly assigned (using a pre-selected random order generated via randomizer.org, with condition previously unknown to the experimenter) to immediate Step 1 or to waitlist (WL).1 Later assessments (post-WL [10 weeks after baseline] for WL condition only, post-Step 1, post-Step 2 eight weeks later, follow-up three months later) were mostly the same. The TDI, PITS, and Treatment Utilization interviews were completed, as were all self-reports (except for motivation at follow-up), and alopecia photos were taken. At Post-Step 1, participants chose whether to enter Step 2. Participants were paid for their time.

Step 1: StopPulling.com

During Step 1, participants were given 10 weeks of free access to StopPulling.com, consisting of assessment, intervention, and maintenance modules.2 In assessment participants self-monitor each urge or pulling episode, recording details such as the behaviors, sensations, feelings, and thoughts preceding pulling, and what was done with the hair afterward. In intervention these data are used to create a list of recommended interventions (e.g., getting rid of tweezers used to pull hair, obtaining toys for use in keeping hands busy, clenching one’s fists to help resist urges). Participants are asked to use three strategies a week, setting goals and rewarding themselves for progress. When goals are met for four weeks, users proceed to maintenance, in which they continue to self-monitor and to use coping interventions.

Step 2 HRT

Participants who chose to enter Step 2 received eight weekly sessions of HRT with one of seven doctoral student therapists, trained and supervised by the last author in consultation with Dr. Charles Mansueto, a TTM expert. The manual was based on Stanley and Mouton (1996); changes included adapting group to individual therapy, extending the length of treatment, and increasing the emphasis on stimulus control while decreasing the focus on relaxation. Our protocol thus highlighted HRT components identified by Bloch et al. (2007): (a) self-monitoring (starting after session 1); (b) awareness training (sessions 2 and 3); (c) stimulus control to prevent opportunities to pull (session 4); and (d) stimulus-response or competing response training, i.e., learning to substitute activities or physically incompatible behaviors when the urge to pull arises (sessions 5 and 6). Sessions 7 and 8 varied as a function of progress, sometimes involving troubleshooting and sometimes maintenance and generalization.

Results

Efficacy of Step 1 web-based self-help

Descriptive data appear in Table 1. Table 2 shows RM ANOVAs with condition, time, and their interaction as independent variables. To account for missing data, we used the multiple imputation method of Lavori, Dawson, and Shera (1995), implemented via PROC MI and MIANALYZE in SAS. Imputed values at week 10 were derived from a multivariate normal model based on participants with complete data for that variable, using baseline symptoms, impairment, length of pulling history, sex, and age as predictors. Given the baseline-week 10 correlations for repeated measures, ranging from .59 (alopecia) to .79 (SDS), the time X treatment interaction tests were adequately (.80) powered for small-to-medium effects (Faul et al., 2007). The only significant interaction was for interviewer-rated symptoms. PITS scores declined more in the immediate condition than in WL, with a small effect at week 10 (d = .21). As noted earlier, PITS interviewers (but not reliability raters) were aware of the assessment time period, though not of experimental condition.

Table 1.

Efficacy of Step 1 Web-based Self-Help: Descriptive Data at baseline and Week 10

| Baseline | Week 10a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Immediate | Waitlist | Immediate | Waitlist | |

| TDIb | 30 (100) | 30 (100) | 23 (82) | 25 (83) |

| PITS | 24.27 (5.15) | 23.37 (3.76) | 20.75 (6.39) | 21.90 (4.63) |

| MGH-HPS | 17.07 (3.37) | 16.77 (4.08) | 14.78 (4.49) | 15.40 (4.34) |

| Alopecia | 5.04 (1.49) | 5.22 (1.56) | 4.73 (1.73) | 5.00 (1.69) |

| SDS | 7.87 (6.30) | 9.03 (6.52) | 6.46 (5.59) | 8.00 (6.36) |

| WHOQOL | 15.77 (1.87) | 15.73 (1.64) | 15.75 (2.12) | 15.50 (2.02) |

Note. TDI = Trichotillomania Diagnostic Interview. PITS = Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale. MGH-HPS = Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale. SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; WHOQOL = World Health Organization Quality of Life. Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. At baseline: N = 60 for PITS, MGH-HPS, QOL; n = 59 for SDS; n = 53 for Alopecia. At Week 10: n = 57 for MGH-HPS, SDS; n = 58 for PITS, QOL; n = 52 for Alopecia.

Week 10 data are from the Post-Step 1 assessment for the Immediate condition and from the Post-waitlist Assessment for the WL condition.

Number (%) of participants meeting diagnostic criteria according to the TDI.

Table 2.

Efficacy of Step 1 Web-based Self-help: Inferential Tests of Immediate vs. Waitlist Condition

| Response | # missing at 10 weeks (baseline) | Models fit with imputed data

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time*TXc | Time+ | TXc+ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| γ̂ | SE | p | γ̂ | SE | p | γ̂ | SE | P | ||

| MGH-HPS | 3 (0) | 0.91 | 0.95 | .34 | 1.82 | 0.47 | .0001 | −0.16 | 0.95 | .87 |

| PITS | 2 (0) | 2.06 | 1.03 | .046 | 1.47 | 0.72 | N/A** | −1.16 | 1.31 | .37 |

| Alopecia | 8 (7) | 0.23 | 0.40 | .57 | 0.24 | 0.20 | .23 | −0.16 | 0.37 | .67 |

| SDS | 3 (1) | 0.29 | 1.08 | .79 | 1.19 | 0.55 | .03 | −1.31 | 1.51 | .38 |

| QOL | 2 (0) | −.23 | 0.36 | .52 | 0.06 | 0.18 | .75 | 0.16 | 0.46 | .73 |

Note. Time = Baseline versus week 10. TXc = Immediate versus Waitlist. Time*TXc = Baseline*Immediate.

From main effects only models if the Time*TXc interaction is not significant (p-value > 0.05).

Time main effect estimate from interaction model is 1.466667 across all 20 imputed data sets for PITS – hence no p-value.

Table 3 shows Step 1 data for the full sample, including WL once they received access.3 Only the PITS changed significantly. Reliable change on the MGH-HPS occurred during Step 1 for eight participants (15%), recovery of normal functioning and clinical significance each for four (8%). Use of StopPulling.com was variable. The median number of different days on which a participant logged on and entered data was 12.5; 19% never entered data. Partial correlations of days of use of the site with post-Step 1 symptoms, controlling for pre-Step 1 symptoms, were nonsignificant for alopecia but significant (p < .05) for MGH-HPS, pr = −.33 and PITS, pr = −.34.

Table 3.

Uncontrolled Step 1 results for full sample

| Pre-Step 1 | Post-Step 1 | t | p | Effect size d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| MGH-HPS | 16.49 | 3.92 | 15.64 | 4.65 | 1.18 | .24 | .19 |

| MGH-T | 7.32 | 1.89 | 7.11 | 2.21 | .61 | .55 | .10 |

| PITS | 23.28 | 5.14 | 21.00 | 5.75 | 3.78 | <.01 | .41 |

| Alopecia | 5.07 | 1.64 | 4.79 | 1.78 | 1.31 | .20 | .16 |

| SDS | 7.96 | 6.59 | 7.11 | 6.48 | 1.54 | .13 | .13 |

| WHOQOL | 15.64 | 1.88 | 15.75 | 2.02 | −.64 | .52 | .06 |

| N | % | N | % | X2 | df | p | |

|

| |||||||

| TDI | 55 | 92 | 48 | 80 | .44 | 1 | .51 |

Note. “Pre-Step 1” is the post-waitlist assessment for those in the WaitList condition, and the baseline assessment for those in the Immediate condition. TDI = Trichotillomania Diagnostic. PITS = Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale. MGH-HPS = Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale. MGH-T = Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale – Truncated version (items 4, 5, and 6; consistent with Mouton-Odum et al., 2006). SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; WHOQOL = World Health Organization Quality of Life; % = percent of participants meeting TTM diagnostic criteria.

Acceptability of stepped care

Treatment satisfaction was high. CSQ-8 scores averaged 25.13 (SD = 4.70) after Step 1, 28.54 (SD = 4.52) after Step 2, and 28.00 (SD = 4.49) at follow-up. By comparison, women with PTSD and substance dependence averaged 24.80 on the CSQ-8 after a CBT program (Najavits, Weiss, Shaw, & Muenz, 1998). Of the 54 participants who completed post-Step 1 assessment and were offered Step 2 HRT, 41 (76%) enrolled in Step 2, and they attended a mean of 7.61 of eight scheduled sessions. There was no significant change in motivation variables during Step 1 in the full sample. For total motivation the mean declined from 23.39 (SD = 7.98) to 22.98 (SD = 8.13), t (53) = 0.64, p = .52. Results were nearly identical for the subsample who did not improve reliably on the MGH-HPS during Step 1.

Self-selection into, and progress during HRT

Participants choosing to enter Step 2 were more symptomatic at post-Step 1. HRT patients (M = 16.75, SD = 3.48) scored higher on the MGH-HPS than did no-HRT participants (M = 12.23, SD = 6.14), t (51) = 3.33, p = .002. They were also more likely to be diagnosed with TTM (95% to 71%), Fisher’s Exact Test p = .033. Differences were in the same direction but nonsignificant for the PITS and alopecia. These tests were adequately powered (.80) only for large effects (d = .91 or greater) (Faul et al., 2007).

Therapist adherence in HRT was high; averaged across raters, 93% of checklist items were coded as present. Patient homework adherence was moderate, with a mean session rating of 2.2 (SD = 0.7). Uncontrolled data on effects of HRT are in Table 4. There were significant and large decreases in both symptom measures and a small-to-medium, significant increase in quality of life. The proportion of participants meeting TTM diagnostic criteria decreased from 95% to 54%. One-half (50%) of HRT patients improved reliably during Step 2 on the MGH-HPS, and 46% recovered normal functioning, with 36% showing clinically significant response. Changes in impairment and alopecia were not significant.

Table 4.

Uncontrolled Results for those who Used Step 2 HRT Treatment

| Post-Step 1 | Post-Step 2 | t | p | Effect size d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| MGH-HPS | 16.61 | 3.41 | 10.47 | 5.22 | 6.94 | <.001 | 1.39 |

| PITS | 22.17 | 5.69 | 16.03 | 6.64 | 9.94 | <.001 | .99 |

| Alopecia | 4.98 | 1.74 | 4.83 | 1.83 | 0.69 | .50 | .08 |

| SDS | 7.72 | 7.46 | 6.75 | 7.26 | 1.64 | .11 | .13 |

| WHOQOL | 15.70 | 2.13 | 16.49 | 2.08 | 4.10 | <.001 | .38 |

Note. PITS = Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale. MGH-HPS = Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale. SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; WHOQOL = World Health Organization Quality of Life.

Maintenance

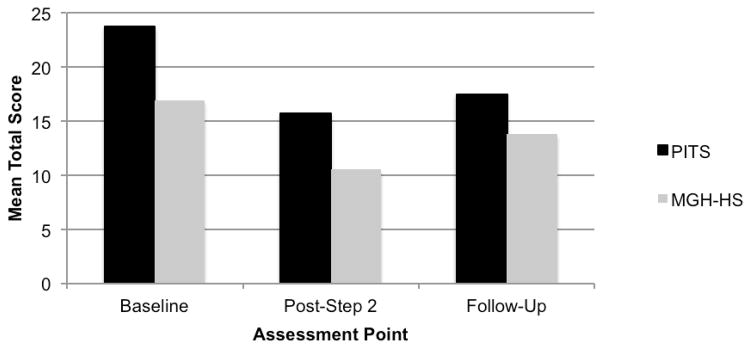

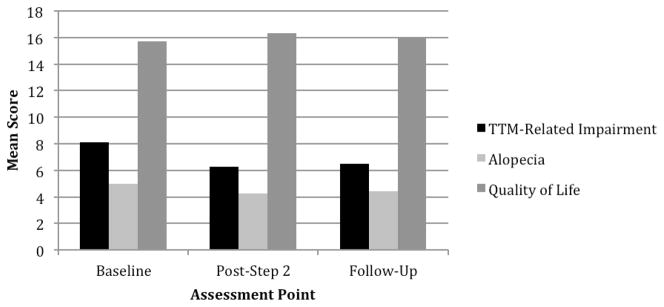

From baseline to post-Step 2 for the full sample, there were reductions on the PITS (23.89 +/− 5.10 to 15.70 +/− 6.61), t (43) = 9.85, p < .001, MGH-HPS (16.92 +/− 3.72 to 10.44 +/− 5.45), t (49) = 8.62, p < .001, alopecia (5.02 +/− 1.53 to 4.23 +/− 1.75), t (31) = 3.05, p < .005, and TTM-related impairment (8.10 +/− 6.61 to 6.25 +/− 7.05), t (47) = 2.55, p = .014, and an increase in quality of life (15.72 +/− 1.77 to 16.35 +/− 2.04), t (48) = 3.32, p = .002. Follow-up means did not differ significantly from post-Step 2 for impairment (6.39 +/− 6.52) or alopecia (4.56 +/− 1.62). However, follow-up was worse than post-Step 2 on quality of life (15.92 +/− 2.31), t (48) = 2.55, p = .014, the PITS (17.48 +/− 7.67), t (41) = 2.48, p = .017, and the MGH-HPS (13.78 +/− 6.08), t (48) = 4.43, p = .017 (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2). All patients met TTM diagnostic criteria at baseline, 51% at post-Step 2, and 67% at follow-up.

Figure 2.1. TTM Symptom Severity Over Time.

The above graph illustrates mean total scores on the PITS (n = 42) and the MGH-HS (n = 49) at baseline, post-step 2, and 3-month follow-up.

Figure 2.2. TTM-Related Impairment, Alopecia, and Quality of Life Over Time.

TTM-Related Impairment (n = 48) = the sum of all three items on the SDS. The above graph illustrates the mean TTM-Related Impairment at baseline, post-step 2, and 3-month follow-up. Alopecia (n = 29) = the average alopecia rating of two independent raters. The above graph illustrates the mean Alopecia at baseline, post-step 2, and 3-month follow-up. Quality of Life (n = 49) = the mean score across the four domains of the WHOQOL that have undergone one transformation. The above graph illustrates the mean Quality of Life at baseline, post-step 2, and 3-month follow-up.

Discussion

This study was an initial evaluation of stepped care for TTM. Efficacy results for Step 1, web-based self-help, were modest. Interviewer-rated symptoms decreased more in StopPulling.com than in WL, but the effect was small, and there was no significant difference on self-rated symptoms, alopecia, impairment, quality of life, or diagnosis. However, those who used the site more often showed more improvement. This was the first randomized trial of StopPulling.com, which bolsters internal validity, but external validity may have been compromised in that participants were required to have Internet access but not necessarily to prefer web-based self-help. Future research might sample those who find the site on their own (as in Mouton-Odum et al., 2006) and invite them to enroll in a randomized controlled trial.

Stepped care seemed highly acceptable. Treatment satisfaction was high. A majority (76%) of participants offered Step 2 HRT entered treatment, and these patients attended 95% of sessions. There was no significant decline in motivation during Step 1, even among non-responders. Utility of stepped care depends not only on acceptability but also the efficiency with which later steps are allocated to patients who need them and can benefit from them. In our sample, self-selection into Step 2 HRT tracked well with post-Step 1 clinical status, and large reductions in symptoms occurred during Step 2. Some relapse was evident on symptoms, diagnoses, and quality of life.

This preliminary study was limited in several ways but can lay the groundwork for more definitive trials. Our follow-up period was brief, and the WL control was only maintained through Step 1, leaving Step 2 HRT results based on an uncontrolled study. Future research could use a longer follow-up and take advantage of randomization while testing strategies in which later steps are adapted to a patient’s early response (Murphy, 2005). Our PITS and TDI interviewers were aware of the assessment time period, though not made aware of experimental condition, and reliability raters were masked to both. Future studies should use complete masking to time period as well as treatment condition. Also, our stepped care model was simple, with two steps and progress through them controlled by patient self-selection. Future research could extend this work by deriving algorithms for (a) automatically advancing to Step 2 those predicted not to respond to Step 1 and (b) identifying at post-Step 1 those who need no more treatment (i.e., have recovered and can be predicted to stay well). Another challenge is to determine how to improve TTM treatment for the one-half who were still diagnosable after treatment and how to reduce relapse. Improved results might entail adding a third step, perhaps specialized behavioral interventions incorporating elements of ACT (Woods & Twohig, 2008) or DBT (Keuthen et al., 2012). Finally, we did not measure costs; future trials could compare stepped care to treatment as usual in cost-effectiveness. Evidence-based stepped care models could help improve access to mental health care (Kazdin & Rabbitt, 2013).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 1R15MH086852-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We are grateful to Charley Mansueto for consultation on the project and for feedback on a draft of this article.

Footnotes

For safety monitoring, WL participants received a check-in call five weeks later. None met criteria for reliable deterioration (>= 6-point increase on the MGH-HPS) or otherwise required immediate intervention.

We completed a mid-Step 1 check-in five weeks after the beginning of Step 1. One participant [who had been in the WL condition] experienced reliable deterioration per the MGH-HPS from post-WL to mid-Step 1 and was therefore offered (and accepted) immediate Step 2 HRT.

Uncontrolled evaluation of Step 1 is based for all participants on change during only the 10 weeks of Step 1 access to StopPulling.com. For those in the Immediate condition, this is Baseline to Post-Step 1. For WL participants, it is Post-Waitlist to Post-Step 1.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Nunn RG. Habit-reversal: A method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1973;11:619–628. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MH, Weisenberger AL, Dombrowski P, Nudel J, Coric V. Systematic review: Pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rabbitt SM. Novel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illness. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:170–191. doi: 10.1177/2167702612463566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keuthen NJ, O’Sullivan RL, Ricciardi JN, Shera D, Savage CR, Borgman AS, Baer L. The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale: I. development and factor analysis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1995;64:141–145. doi: 10.1159/000289003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuthen NJ, Rothbaum BO, Fama J, Altenburger E, Falkenstein MJ, Sprich SE, Welch SS. DBT-enhanced cognitive-behavioral treatment for trichotillomania: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2012;1:1–9. doi: 10.1556/JBA.1.2012.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Dawson R, Shera D. A multiple imputation strategy for clinical trials with truncation of patient data. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14:1913–1925. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner C, Stein DJ, Woods D, Pauls DL, Franklin ME, Loerke EH, Keuthen NJ. The validity of DSM-IV-TR criteria B and C of hair-pulling disorder (trichotillomania): Evidence from a clinical study. Psychiatry Research. 2011;189(2):276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton-Odum S, Keuthen NJ, Wagener PD, Stanley MA, Debakey ME. Stoppulling.com: An interactive, self-help program for trichotillomania. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2006;13:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2005.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA. An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment strategies. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:1455–1481. doi: 10.1002/sim.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR, Muenz LR. “Seeking Safety”: Outcome of a new cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:437–456. doi: 10.1023/A:1024496427434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier LG, Tuson KM, Haddad NK. Client motivation for therapy scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;68:414–435. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6802_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts EJ, Brandt BC, Woods DW. The effects of severity and causal explanation on social perceptions of hair loss. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2012;1:336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Ninan PT. The assessment of trichotillomania. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1994;32:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York, NY: Scribner’s; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Mouton SG. Trichotillomania treatment manual. In: Van Hasselt VB, Hersen M, editors. Sourcebook of psychological treatment manuals for adult disorders. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 657–687. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Franklin ME, Diefenbach GJ, Gross A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric trichotillomania: an open trial. Presented to the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Reno, NV. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winchel RM, Jones JS, Molcho A, Parsons B, Stanley B, Stanley M. The Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale (PITS) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1992;28:463–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Flessner CA, Franklin ME, Keuthen NJ, Goodwin RD, Stein DJ Trichotillomania Learning Center-Scientific Advisory Board. The trichotillomania impact project (TIP): Exploring phenomenology, functional impairment, and treatment utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1877–1888. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Twohig MP. Trichotillomania: An ACT-enhanced behavior therapy approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]