Abstract

Purpose

To develop a practical, efficient, and valid pediatric global health measure that would be useful for clinical, quality improvement, and research applications.

Methods

Using the PROMIS mixed-methods approach for item bank development, we identified an item pool that was well understood by children as young as age 8 years, and tested its psychometric properties in an internet panel sample of 3,635 children 8–17 years-old and 1,807 parents of children 5–17 years-old.

Results

The final version of the pediatric global health measure included 7 items assessing general, physical, mental, and social health. Four of these items had the same wording as the PROMIS adult global health measure. Internal consistency was 0.88 for the child-report form and 0.84 for the parent form; both had excellent test-retest reliability. The measures showed factor invariance across age categories. There was no differential item functioning by age, gender, race, or ethnicity. Because the measure includes the general health rating question, it is possible to estimate the pediatric global health scale using this widely used single item.

Conclusions

The PROMIS Pediatric Global Health measure is a brief and reliable 7-item summary assessment of a child’s self-reported health. Future work will attempt to statistically link this pediatric form with the PROMIS adult global health measures to create a single global health metric that can be used across the life course.

Keywords: patient-reported outcome, quality of life, health status, child, global health

Introduction

Assessments of an individual’s perceptions of his or her health overall (“global health”) are desirable for performance assessment in clinical care, research, and population surveillance. The integration of patient reported outcomes (PROs) into an overall performance measurement strategy, whereby PRO data are aggregated for an accountable healthcare entity or geopolitical unit, is highly congruent with aspirations for moving toward a value-driven health care system [1].

There is no longer a debate regarding children’s ability to report on their health and health-related experiences. Theoretical [2] and qualitative assessments [3, 4] of the cognitive skills necessary for self-report show that children as young as 8 years-old can accurately respond to developmentally appropriate questions on their feelings, functioning, perceptions, and well-being. Over the last two decades there has been a substantial increase in the number of pediatric generic [5] and disease-specific [6] health-related quality of life instruments. Despite this proliferation of measures, child-reported outcome tools are rarely used in clinical trials [6] or quality improvement applications, indicating that obstacles remain to their adoption. Barriers to adoption such as the need for a simple, short, and practical measure and the lack of a single measure that can assess the same construct over the lifespan will need to be addressed as well.

The most commonly used global health item asks respondents to rate their health in general. That single indicator has been associated with future health [7] and healthcare utilization [8] in a large number of studies. The widespread usage of the general health item stems from its ease of administration, applicability across the lifespan, and public domain availability. Its major limitation is lack of variation within an individual over time or within a population, particularly children whose self reported assessments have substantial ceiling effects, which limit its usefulness as a measure to detect change or describe small differences between individuals and populations.

Simon and colleagues [9] found that scores from a 12-item index of global health for 6–17 year-old youth based on the conceptual framework of the Child Health and Illness Profile [10] decreased with child age, severity of illness, obesity, and unmet healthcare needs, while it increased with socio-economic status. Of note, children who rated their health as excellent on the general health item had index scores that ranged over 40 points on a scale with a 0–100 range, indicating a large ceiling effect for the general health item.

The KIDSCREEN-10 provides a summary measure of mental health; it decreases with age and presence of a chronic condition, whereas it increases with family social influence [11]. The PedsQL provides a 23-item score for global health [12] that incorporates a broader range of concepts (i.e., physical and psychosocial domains) than the KIDSCREEN-10. However, a 23-item index is long for a summary measure of global health, and the PedsQL is not freely available. Neither the KIDSCREEN-10 nor the PedsQL was developed as part of a life course global health assessment system that assesses comparable content among pediatric and adult populations. This is true for virtually all pediatric measures, which are designed for children and youth only.

This study used a mixed-methods approach for instrument development [13] to develop a pediatric version of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) global health measure [14, 15]. Our objective was to produce a practical and efficient measure of pediatric global health, conceptually harmonized with the PROMIS adult form to enable life course assessment of the same construct. This new PROMIS pediatric measure was intended to provide an efficient (fewer than 10 items) summary of a child’s physical, mental, and social health, the three dimensions of the PROMIS conceptual framework [16]. Assessment of these three dimensions of health would distinguish the measure from the KIDSCRENN-10, which reflects a child’s mental health and quality of life. We also intended that it would be shorter, and thus more efficient, than the PedsQL. In sum, the PROMIS pediatric global health’s distinguishing characteristics would be: (1) comprehensive assessment of physical, mental, and social health; (2) brief and practical; (3) conceptual harmonization with a similar adult form enable life course assessment; (4) integration into the full PROMIS pediatric measurement system; and, (5) useful for research, quality assessment and improvement, population surveillance, and clinical practice.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved all study procedures (protocols 10-007684 and 12-009560). Informed consent for child participants was obtained from parents and assent was obtained from children.

Interviews with Children and Parents

We conducted 36 interviews: 21 with children 8–17 years old (7 aged 8–10 years, 5 aged 11–13 years, 9 aged 14–17 years), half of whom were male, and 15 with parents. Participants were recruited from community dental and vision screening events in Philadelphia; all resided within the city. These interviews elicited the individual’s concepts of global health, how they experience it, and examined their understanding of the global health items using cognitive debriefing methods. Interviews were conducted until saturation was achieved—i.e., when participants of a broad age range failed to provide novel information [17]. Parents reviewed the PROMIS adult global health measure and were asked what concepts were missing. They supported the addition of a family life item (parents listen to your ideas) and expressed concern that children would not understand the adult social health questions. A concept was considered saturated if it was elicited in at least one, but not the last, interview and if enough information had been obtained to fully understand the meaning and importance of the concept to children [17].

Cognitive debriefing interviews were done to assess comprehension, recall, and other cognitive processes that could be remediated through question rewording, reordering, or more extensive instrument revisions [18]. Before the cognitive interview, participants completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire with all items in the initial item pool. For each item, interviewees read the question aloud and stated the meaning of the question using their own words. The interviewer then asked, “How did you answer that question?’’ and ‘‘Why did you choose that answer?’’ Responses to cognitive interview probes were coded for the degree to which children’s understanding of the question was consistent with the item definition.

Item Pool Development

Based on input from a panel of pediatric and adult health outcomes researchers, participants in the PROMIS cooperative group, we postulated that the content of the adult global health measure would be applicable to children, although in some cases alternative, developmentally appropriate items would be required.

The item pool development aim was to create a parsimonious measure of pediatric global health that was conceptually equivalent to the PROMIS adult global health measure [14] with overlap of items to permit possible scale linking. The initial item pool included all 10 items from the PROMIS adult measure. For each of the four broad concepts—quality of life, physical health, mental health, and social health, we added additional, developmentally appropriate content, selecting items from the Healthy Pathways scales, which our team developed for children and adolescents [19, 20]. We chose items from these scales based on their content and level of item discrimination from IRT models [20]. Specifically, six additional items were added. To assess pain, we included having pain that really bothers you. Emotional health was augmented with feeling sad and feeling worried. Social health was expanded to include having fun with friends and parents listen to your ideas. Our previous work indicated that children experience fatigue as a lack of energy and younger children had difficulty understanding the word fatigue [3]. Thus, we replaced the adult fatigue item with having a lot of energy. Finally, we added an item feeling proud to capture both children’s satisfaction with self as an element of quality of life and their feelings of positive affect.

Cognitive interviews of the 16 items prompted deletion of both adult social health items (satisfaction with social activities and relationships and carry out social roles) and the adult item bothered by emotional problems item because of poor comprehension. Children, youth, and parents thought that the adult physical functioning item (carry out your everyday physical activities such as walking, climbing stairs, carrying groceries, or moving a chair) was not relevant to their global health. Because limitations in physical functioning are so uncommon in childhood, we removed this item. The adult pain rating (0–10 scale) was deleted because children preferred (assessed during the cognitive debriefing interviews) the Healthy Pathways item (pain that really bothers you). The remaining 11 items were administered in the field test.

Field Test Study Designs

We administered the 11-item global health items via web-based survey to participants and their children in a national internet panel maintained by Op4G (see Op4G.com for more detail). The field test involved evaluating nine additional domains (physical activity, sedentary activity, psychological distress, somatic distress, life satisfaction, positive affect, meaning and purpose, family belonging, and family involvement) in addition to the pediatric global health measure. Each participant completed all the items for a sub-set of domains. There were six forms, five of which included the pediatric global health item pool. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the six forms. Data were collected over a 10-day period in December 2011. The surveys were administered in English.

A separate test-retest sample was obtained from Op4g and data from that group was collected during January 2012. Participants completed a retest between 1–2 weeks after the initial test.

Field Test Participants

Parents were asked to forgo the survey if their child had a cognitive limitation that would preclude him or her from responding independently to the survey. Op4G maintains a national sample, and participants are required to update demographic information regularly, including information about presence and age of children. Op4G sent invitations to parents of children ages 5–17 years old. We specified quotas for age-sex-form combinations, and recruitment was done on a rolling basis, stopping for a given age-sex-form band once the quota had been satisfied.

When both a parent and a child were participating in the survey, parents completed their questionnaire first, and then were prompted to have their child complete a questionnaire. Each questionnaire had about 130 questions and required about 20 minutes to complete; items were presented on a computer screen.

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the field test child/youth and parent samples. A total of 3,635 children and youth 8–17 years-old and 1,807 parents of children and youth 5–17 years completed the global health measure. We obtained the 3-digit zip codes from parents and linked them to census data to determine rurality and region of residence. Parents were asked if their child had a condition that was expected to last more than 12 months. If they responded yes, they were asked to provide the name of the condition. Responses that indicated a chronic condition, based on our clinical review of the answers to the open-ended question, were categorized as a chronic condition. Compared with national statistics (which we obtained from www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables.asp), the child/youth sample had a lower proportion of Hispanics (10% versus 24%), Black/African Americans (8% versus 15%), but a greater share of rural children (15% versus 9%). Nonetheless, the proportion of small racial groups, such as Asians, Multiple Races, American Indian/Alaskan Native were quite similar to national averages. Among the parent-proxy sample, the ages of their children were 5% 5–7 years, 35% 8–10 years, 25% 11–13 years, and 35% 14–17 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children and Parent Participants.

| Characteristics | Children (n=3635)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Percentage | |

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| 8–10 | 1799 | 50% |

| 11–13 | 752 | 20% |

| 14–17 | 1084 | 30% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1680 | 46% |

| Male | 1955 | 54% |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 370 | 10% |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 3265 | 90% |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 2948 | 81% |

| Black/African American | 282 | 8% |

| Asian | 162 | 4% |

| Multiple Races | 178 | 5% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 46 | 1% |

| Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 8 | <1% |

| Other | 5 | <1% |

| Missing | 6 | <1% |

|

| ||

| Geographic Area | ||

| Rural | 559 | 15% |

| Urban/Suburban | 3076 | 85% |

|

| ||

| Region in the U.S. | ||

| Northeast | 1000 | 28% |

| South | 1348 | 37% |

| Midwest | 589 | 16% |

| West | 698 | 19% |

|

| ||

| Parent-Proxy Sample (n=1807) | ||

|

| ||

| Child’s Age, years | ||

| 5–7 | 105 | 6% |

| 8–10 | 637 | 35% |

| 11–13 | 447 | 25% |

| 14–17 | 618 | 34% |

|

| ||

| Chronic Condition | ||

| Yes | 421 | 23% |

| No | 1386 | 77% |

|

| ||

| Annual Household Income | ||

| Less than $40,000 | 518 | 29% |

| $40,000 or more | 1288 | 71% |

|

| ||

| Medical Insurance | ||

| Public (Medicaid, SCHIP) | 1165 | 64.5% |

| Private | 541 | 29.9% |

| Uninsured | 101 | 5.6% |

Analysis Plan

All analyses were replicated for child-reported data (n=3,635) and parent-proxy data (n=1,807). Items were administered using 5 response categories (scored 1–5). Descriptive analyses included estimates of item and scale-level means, standard deviations, floor effects, ceiling effects, and missingness. We estimated the corrected item-total correlations and computed Cronbach’s alpha for the sample overall and by age group. In this and additional analyses, age group was categorized as 8–10 years, 11–13 years, and 14–17 years. Test-retest reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient.

The item pool was evaluated to assess the item response theory assumptions of unidimensionality, local independence, and monotonicity. The unidimensionality assumption was tested by fitting exploratory and confirmatory factor analytic models using MPlus 6.1. In order to assess the extent to which the item pool measures a singular and dominant health trait, we examined the ratio of first and second eigenvalues from the exploratory factor analysis with maximum likelihood extraction and oblique rotation. Next, we examined the fit indices (Tucker-Lewis Index, Comparative Fit Index, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) from a single factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) that evaluated polychoric correlations using the weighted least square with adjustments for the mean and variance (WLSMV) estimator [21].

Local independence was assessed by examining the residual correlation matrix after fitting the one-factor CFA model. We flagged locally dependent items by identifying pairs with high residual correlations (absolute value greater than 0.2). Monotonicity (probability of endorsing an item response indicative of better health status increases as the underlying level of health increases) was confirmed by the presence of non-overlapping item response thresholds.

After establishing the assumptions of unidimensionality, local independence, and monotonicity, we fit Samejima’s Graded Response model using IRTPRO 2.1. We inspected each item’s discrimination (a) and thresholds (b) values to determine whether the items cover the full range of global health. We also examined item and test information to assess measurement precision across the underlying range of global health.

Finally, we performed tests for differential item functioning (which signifies the probability of an item response differing between subgroups), implemented with the “lordif” package in R [22], which uses ordinal logistic regression and item response theory to estimate the scale score. We examined both uniform and non-uniform DIF across age, gender, ethnicity, and race. We flagged any item that showed a >1% change in the McFadden pseudo R2 measure [23].

Results

Item Deletions

Item selection was guided by the qualitative and quantitative data obtained from children. We deleted the pain and energy items, because they were non-monotonic (disordered item thresholds) and poorly associated with the underlying latent trait (CFA factor loadings lower than 0.30). For the child-report form, the item feeling worried had a high residual correlation with feeling sad, and it was deleted. Similarly the item feeling proud had a high residual correlation with global health in the parent-report form, and it was also deleted. The final 7 items include concepts within the physical, mental, and social health dimensions (see Appendices 1 and 2 for item wording for both the child and parent report forms). None of these items showed any residual correlation (all <0.20) with each other for either the child-report or parent-report forms.

Appendix 1.

Pediatric Global Health (PGH-7) Items, Child-Report Form

| Item Concept | Item stem | Responses |

| General health | In general, would you say your health is: | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Quality of life | In general, would you say your quality of life is: | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Physical health | In general, how would you rate your physical health? | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Mental health | In general, how would you rate your mental health, including your mood and your ability to think? | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Sad | How often do you feel really sad? | 5 = Never 4 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes 2 = Often 1 = Always |

| Fun with friends | How often do you have fun with friends? | 5 = Always 4 = Often 3 = Sometimes 2 = Rarely 1 = Never |

| Parents listen to ideas | How often do your parents listen to your ideas? | 5 = Always 4 = Often 3 = Sometimes 2 = Rarely 1 = Never |

Appendix 2.

Pediatric Global Health (PGH-7) Items, Parent-Proxy Report Form

| Concept | Item stem | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| General health | In general, would you say your child’s health is: | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Quality of life | In general, would you say your child’s quality of life is: | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Physical health | In general, how would you rate your child’s physical health? | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Mental health | In general, how would you rate your child’s mental health, including mood and ability to think? | 5 = Excellent 4 = Very good 3 = Good 2 = Fair 1 = Poor |

| Sad | How often does your child feel really sad? | 5 = Never 4 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes 2 = Often 1 = Always |

| Fun with friends | How often does your child have fun with friends? | 5 = Always 4 = Often 3 = Sometimes 2 = Rarely 1 = Never |

| Parents listen to ideas | How often does your child feel that you listen to his or her ideas? | 5 = Always 4 = Often 3 = Sometimes 2 = Rarely 1 = Never |

Descriptive Analyses

At the scale level, the Pediatric Global Health Measure 7-Item Form (PGH-7) had no floor effects, and just 5% of the child and parent-proxy scores were at the ceiling. Within age groups, parents and children provided similar estimates of global health, which decreased slightly with age (Table 2). Item-scale correlations (corrected for item overlap) for the child-reported PGH-7 ranged from 0.42 (Feel sad) to 0.78 (Quality of life) and for the parent-proxy form from 0.30 (Feel sad) to 0.71 (Quality of life).

Table 2.

| Results from Cognitive Interviews with 21 Children Ages 8–17 year-old | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item Name | Item Wording | Children’s Understanding |

| General health | In general, would you say your health is: |

|

| Quality of life | In general, would you say your quality of life is: |

|

| Physical health | In general, how would you rate your physical health? |

|

| Mental health | In general, how would you rate your mental health, including your mood and your ability to think? |

|

| Feeling sad | How often do you feel really sad? |

|

| Fun with friends | How often do you have fun with friends? |

|

| Parents listen to ideas | How often do your parents listen to your ideas? |

|

| Descriptive statistics for the PGH-7 items and scales

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHILD REPORT (n=3635) | PARENT-PROXY REPORT (n=1807) | |||||||||

| Mean | Std Dev | % Floor | % Ceiling | % Missing | Mean | Std Dev | % Floor | % Ceiling | % Missing | |

|

|

||||||||||

| Items (range 1–5) | ||||||||||

| General health | 4.21 | 0.86 | 0.9 | 44.0 | 0 | 4.26 | 0.80 | 0.4 | 44.9 | 0 |

| Quality of life | 4.17 | 0.89 | 0.9 | 43.0 | 0 | 4.26 | 0.79 | 0.4 | 44.0 | 0 |

| Physical health | 4.20 | 0.90 | 1.0 | 45.8 | 0 | 4.26 | 0.81 | 0.3 | 46.1 | 0 |

| Mental health | 4.18 | 0.95 | 1.3 | 46.7 | 0 | 4.14 | 0.96 | 1.4 | 44.1 | 0 |

| Feel sad | 3.75 | 0.88 | 2.6 | 15.5 | 0 | 3.75 | 0.91 | 2.4 | 16.3 | 0 |

| Fun with friends | 4.23 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 45.4 | 0 | 4.14 | 0.84 | 0.8 | 37.9 | 0 |

| Parents listen to ideas | 3.97 | 0.93 | 1.5 | 32.9 | 0 | 4.11 | 0.83 | 0.8 | 35.3 | 0 |

| PGH-7 (range 7–35) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Overall | 28.71 | 4.67 | 0 | 5.8 | 0 | 28.92 | 4.23 | 0 | 5.0 | 0 |

| Age Group | ||||||||||

| 5–7 years-old | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 31.05 | 3.28 | 0 | 9.5 | 0 |

| 8–10 years-old | 29.44 | 4.27 | 0 | 6.7 | 0 | 29.21 | 4.13 | 0 | 5.7 | 0 |

| 11–13 years-old | 28.32 | 4.81 | 0 | 5.3 | 0 | 28.60 | 4.27 | 0 | 4.3 | 0 |

| 14–17 years-old | 27.79 | 5.01 | 0 | 4.5 | 0 | 28.49 | 4.33 | 0 | 4.2 | 0 |

Dimensionality, Monotonicity, and Local Dependence

For the child-reported PGH-7, the first factor from the EFA explained 60% of the variance and the ratio of the first two eigenvalues was 5.2. For the parent-proxy version, the first factor explained 57% of the variance and the ratio of the first two eigenvalues was 4.6. These findings suggested a single underlying dimension. Adequate uni-dimensionality was further supported by both parallel analysis and scree test. In addition, comparable levels of variance explained by the first factor and the ratio of the first two factors were observed across age groups.

Single-factor confirmatory factor analyses fit the data reasonably well for the child-reported form (CFI=0.98; TLI=0.96; RMSEA=0.17) and the parent-proxy form (CFI=0.97; TLI=0.95; RMSEA=0.17). We conducted age-specific confirmatory factor analyses to examine factor invariance by age (Table 3). Model fit statistics and factor loadings were comparable across age groups for the child/youth and parent-proxy samples, indicating age-related factor invariance. A multi-group model further supported the age-related test equivalence. All items in both the child-reported and parent-proxy versions showed a monotonic increase in PGH-7 score across response options.

Table 3.

Model fit and factor loadings from confirmatory factor analysis by age of child

| Child-Reported PGH-7 | |||||

| Age of Child | |||||

| Overall | 8–10y | 11–13y | 14–17y | ||

| n | 3635 | 1799 | 752 | 1084 | |

| CFI | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | |

| TLI | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | |

| RMSEA | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.18 | |

| Item | Factor Loadings | ||||

| General health | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |

| Quality of life | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 | |

| Physical health | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| Mental health | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.87 | |

| Feel sad | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.49 | |

| Fun with friends | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.64 | |

| Parents listen to ideas | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.59 | |

| Parent-Reported PGH-7 | |||||

| Age of Child | |||||

| Overall | 5–7y | 8–10y | 11–13y | 14–17y | |

| n | 1807 | 105 | 637 | 447 | 618 |

| CFI | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| TLI | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| RMSEA | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.19 |

| Item | Factor Loadings | ||||

| General health | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Quality of life | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

| Physical health | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.90 |

| Mental health | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Feel sad | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.32 |

| Fun with friends | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Parents listen to ideas | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.64 |

Reliability

Internal consistency alpha was 0.88 for the child/youth sample and 0.84 for the parent-proxy sample. Age-specific, child-reported PGH-7 internal consistency alpha ranged from 0.86 (8–10 year-olds) to 0.87 (14–17 year-olds), and for parent-proxy from 0.82 (5–7 year-olds) to 0.85 (11–13 year-olds). The two-week test-retest reliability coefficients were 0.73 for the child-reported PGH7 with little variation by age group: 8–10 years-old 0.71, 11–13 years-old 0.75, and 14–17 years-old 0.66. The parent-proxy test-retest reliability was 0.74.

IRT Model

We estimated item parameters from the IRT graded response model for both forms of the PGH-7 (Table 4). Item discriminations ranged for the child-reported PGH-7 from a low of 1.02 (Feeling Sad) to a high of 4.18 (Physical health) and for the parent-proxy form a low of 0.76 (Feeling Sad) to a high of 4.17 (General Health). The range of item thresholds indicated wide coverage of the underlying trait from approximately −3 to +2 for the child-reported form and −4 to +2 for the parent-proxy form.

Table 4.

PGH-7 item parameters from an IRT graded response model

| Child-Reported PGH-7 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 |

| General health | 3.98 | −2.62 | −1.94 | −0.95 | 0.15 |

| Quality of life | 3.44 | −2.69 | −1.85 | −0.95 | 0.18 |

| Physical health | 4.18 | −2.55 | −1.80 | −0.89 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 3.16 | −2.55 | −1.77 | −0.91 | 0.08 |

| Feel sad | 1.02 | −4.02 | −2.76 | −1.00 | 1.96 |

| Fun with friends | 1.43 | −3.99 | −2.91 | −1.44 | 0.18 |

| Parents listen to ideas | 1.16 | −4.13 | −2.82 | −1.01 | 0.77 |

| Parent-Reported PGH-7 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 |

| General health | 4.17 | −2.92 | −2.12 | −1.06 | 0.12 |

| Quality of life | 2.90 | −3.20 | −2.28 | −1.21 | 0.16 |

| Physical health | 3.85 | −3.02 | −2.09 | −1.05 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 2.21 | −2.86 | −1.87 | −0.99 | 0.18 |

| Feel sad | 0.76 | −5.25 | −3.16 | −1.41 | 2.39 |

| Fun with friends | 1.37 | −4.21 | −2.92 | −1.37 | 0.48 |

| Parents listen to ideas | 1.25 | −4.49 | −3.13 | −1.43 | 0.64 |

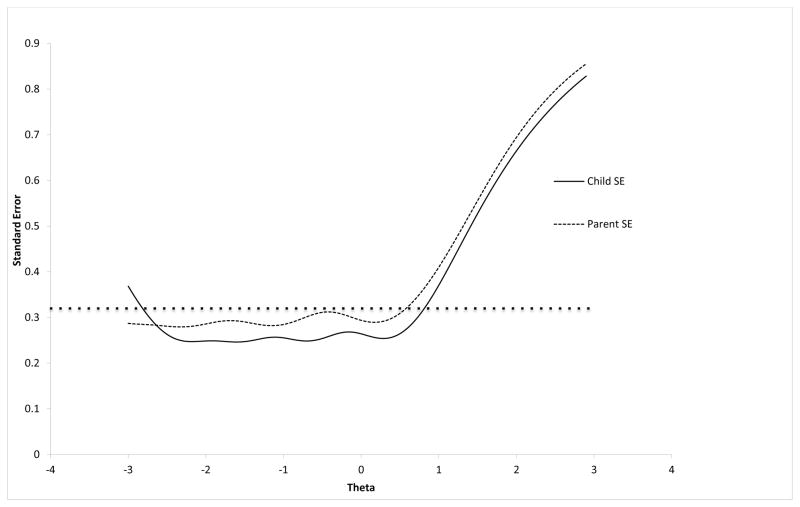

The child-report PGH-7 provided slightly more information, and as a result lower standard errors across the range of theta, than the parent-proxy PGH-7 (Figure).

Figure.

Standard error by theta score for the Child PGH-7 and the Parent-Proxy PGH-7.

*The dotted line represents a standard error of approximately 0.32 which is equivalent to a reliability estimate of 0.90

Differential Item Functioning

We examined each of the items for uniform and non-uniform differential item functioning (DIF) for age, sex, ethnicity, and race covariates. We found no item with substantive DIF across the socio-demographic characteristics for either child-report or parent-proxy report, using a criterion of 1% change in the pseudo-R2 using the McFadden statistic.

Discussion

The PROMIS Pediatric Global Health (PGH-7) items are well understood by children as young as 8 years-old. Both a child-report form for children and youth 8–17 years-old and a parent-proxy form for children and youth 5–17 years-old are available. Both versions had test-retest reliability estimates above 0.80, indicating excellent stability. The measure is unidimensional and factor invariant by the age of the child. We have calibrated the seven items using an IRT graded response model, and the scale has low floor and ceiling effects.

Global health represents an individual’s overall assessment of their health. We based the conceptual framework of the PGH-7 on the PROMIS tripartite division of self-reported health into physical, mental, and social health components [16]. The item (Quality of life) assesses a children’s overall well-being, one item evaluates physical health, two mental health, two social health, and one general health. The measure is conceptually equivalent to the PROMIS adult global health measure [14] and the final version of the PGH-7 includes four of the same items as its adult counterpart. Future work will evaluate the validity of the PGH-7 by contrasting it to existing measures of self-reported health and assessing its responsiveness to clinical change. In addition, the conceptual equivalence of the PGH-7 with the PROMIS adult global health measure suggests the possibility of linkage, which places the pediatric version on the adult scale to form comparable scores, thereby enabling longitudinal research across the pediatric-adult transition.

A major advantage of the PGH-7 is its brevity, which lowers respondent burden and increases efficiency. It takes children, youth, and parents no more than 1–2 minutes to complete. Although the single item general health question is even shorter, the PGH-7 provides a greater range of variability and is more likely to be responsive to changes in health that result from healthcare interventions or naturally occurring circumstances. This efficiency is likely to enhance its adoption in both research and performance assessment applications. Furthermore, by including the general health indicator in the PGH-7, surveys that include that single item can be scored on the PGH scale, which allows for comparisons across studies that use either the PGH-7 or the general health indicator.

In recognizing patients as the authoritative source of their health experiences before, during, and after treatment, much opportunity exists in the ability of performance measurement using PROs to drive continuous quality improvement activities. Assessing the patient's view of their functioning and well-being is the basis for facilitating successful patient-provider communication, effective processes of care, appropriate treatments, and ultimately improved patient outcomes. PRO-based performance measurement, therefore, represents an important mechanism for accelerating performance improvements and increasing accountability at various levels of the health care system.

The study samples were obtained entirely from an Internet panel. Parents of children aged 5–17 years were recruited through an internet panel survey company. Both parents and children completed the questionnaires on the computer with no direct observation by an interviewer. Internet panels have been used for adult instrument development, but there have been few attempts to use this approach with children. In another study, we compared the psychometric properties of several instruments, but not the PGH-7, administered to age-matched samples of children recruited and assessed through this Internet panel and in schools, where the children were directly observed as they completed the questionnaires on paper [24]. Factor structure, internal consistency, and scale information were comparable across administration modality subgroups. Differential item functioning analyses indicated that administration modality did not impact the probability of observing particular item response patterns beyond that which was attributable to the respondent’s level of the measured health attribute. Items administered using the two modalities were similar in the degree to which they discriminated among youth with varying levels of health. These findings are reassuring, because the advent of computerized survey administration linked to electronic health records will increase the number of children and adults who complete these measures at home via the internet.

Purchasers, health care providers, and other key stakeholders have identified child health outcomes as an unmet need in pediatric health and health care performance measurement [25–28]. Viewing children through the lens of their well being and functioning rather than solely according to risk based and disease-specific measures is an important shift in perspective that redirects attention toward the end goal of helping children become flourishing individuals. The advantage of a measure like the PGH-7 is that it is not based on segmentation of the pediatric population by a condition, but is a cross cutting measure that provides an evaluation of health overall regardless of disease or other clinical category. One of the greatest strengths of the PGH-7 is that it is a highly inclusive measure that would allow any entity to assess the vast majority of its pediatric population.

We believe that researchers can use the PGH-7 to assess global health of children from ages 5–17 years-old. The measure will be useful for clinical, performance improvement, and research applications. Investigators may be interested in evaluating the overall score or item-level scores to glean information about sub-components of global health. Next steps in its development will include evaluating validity as compared with other measures of self-reported global health, determining the measure’s responsiveness to clinical change, and linking the PGH-7 with the PROMIS adult global health measure.

Acknowledgments

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an NIH Roadmap initiative to develop a computerized system measuring PROs in respondents with a wide range of chronic diseases and demographic characteristics. PROMIS II was funded by cooperative agreements with a Statistical Center (Northwestern University, PI: David Cella, PhD, 1U54AR057951), a Technology Center (Northwestern University, PI: Richard C. Gershon, PhD, 1U54AR057943), a Network Center (American Institutes for Research, PI: Susan (San) D. Keller, PhD, 1U54AR057926) and thirteen Primary Research Sites which may include more than one institution (State University of New York, Stony Brook, PIs: Joan E. Broderick, PhD and Arthur A. Stone, PhD, 1U01AR057948; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Heidi M. Crane, MD, MPH, Paul K. Crane, MD, MPH, and Donald L. Patrick, PhD, 1U01AR057954; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD and Karon Cook, PhD, 1U01AR052171; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, PI: Darren A. DeWalt, MD, MPH, 2U01AR052181; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PI: Christopher B. Forrest, MD, PhD, 1U01AR057956; Stanford University, PI: James F. Fries, MD, 2U01AR052158; Boston University, PIs: Stephen M. Haley, PhD and David Scott Tulsky, PhD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), 1U01AR057929; University of California, Los Angeles, PIs: Dinesh Khanna, MD and Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, 1U01AR057936; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, 2U01AR052155; Georgetown University, PIs: Carol. M. Moinpour, PhD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) and Arnold L. Potosky, PhD, U01AR057971; Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, PI: Esi M. Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, 1U01AR057940; University of Maryland, Baltimore, PI: Lisa M. Shulman, MD, 1U01AR057967; and Duke University, PI: Kevin P. Weinfurt, PhD, 2U01AR052186). NIH Science Officers on this project have included Deborah Ader, PhD, Vanessa Ameen, MD, Susan Czajkowski, PhD, Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Lawrence Fox, MD, PhD, Lynne Haverkos, MD, MPH, Thomas Hilton, PhD, Laura Lee Johnson, PhD, Michael Kozak, PhD, Peter Lyster, PhD, Donald Mattison, MD, Claudia Moy, PhD, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, William Riley, PhD, Ashley Wilder Smith, PhD, MPH, Susana Serrate-Sztein,MD, Ellen Werner, PhD and James Witter, MD, PhD. This manuscript was reviewed by PROMIS reviewers before submission for external peer review.

Funding: This project was supported by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U18HS020508) and the National Institutes of Health (U01AR057956–02).

Abbreviations

- PRO

Patient-Reported Outcome

- PROMIS

Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System

- PGH

Pediatric Global Health

- TLI

Tucker-Lewis Index

- CFI

Comparative Fit Index

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- EFA

Exploratory Factor Analysis

References

- 1.Deutsch A, Smith L, Gage B, Kellher C, Garfinkel D. [Accessed July 9, 2013];Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement: National Quality Forum. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=71827.

- 2.Bevans KB, Riley AW, Moon J, Forrest CB. Conceptual and methodological advances in child-reported outcomes measurement. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Research. 2010;10(4):385–396. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebok G, Riley A, Forrest C, Starfield B, Green B, Robertson J, Tambor E. Elementary school-aged children's reports of their health: a cognitive interviewing study. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1016693417166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irwin DE, Varni JW, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: a patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajmil L, Herdman M, Fernandez de Sanmamed MJ, Detmar S, Bruil J, Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M, Simeoni MC, Auquier P, Group K. Generic health-related quality of life instruments in children and adolescents: a qualitative analysis of content. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke SA, Eiser C. The measurement of health-related quality of life (QOL) in paediatric clinical trials: a systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(3):267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Services Research. 2005;40(4):1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon AE, Chan KS, Forrest CB. Assessment of children's health-related quality of life in the United States with a multidimensional index. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e118–126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starfield B, Riley AW, Green BF, Ensminger ME, Ryan SA, Kelleher K, Kim-Harris S, Johnston D, Vogel K. The adolescent child health and illness profile. A population-based measure of health. Medical Care. 1995;33(5):553–566. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Rajmil L, Herdman M, Auquier P, Bruil J, Power M, Duer W, Abel T, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents' well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2010;19(10):1487–1500. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Tucker C, Riley AW, Ravens-Sieberer U, Gardner W, Pajer K. Commentary: The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMISR) for Children and Youth: Application to Pediatric Psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37(6):614–621. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(7):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revicki DA, Kawata AK, Harnam N, Chen WH, Hays RD, Cella D. Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(6):783–791. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, Christodolou C, Cook K, Hahn EA, Cella D. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res. 19(9):1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, Crawford B, Rosa K. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2010;19(8):1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortune-Greeley AK, Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Williams MS, Keefe FJ, Reeve BB, Willis GB, Weinfurt KP. Using cognitive interviews to evaluate items for measuring sexual functioning across cancer populations: improvements and remaining challenges. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2009;18(8):1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9523-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bevans KB, Riley AW, Forrest CB. Development of the Healthy Pathways Parent-Report Scales. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2012;38(2):173–191. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bevans KB, Riley AW, Forrest CB. Development of the healthy pathways child-report scales. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2010;19(8):1195–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthen B, duToit SHC, Spisic D. Robust inference using weighted least squared and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. [Accessed July 9, 2013];1997 Available at: http://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/muthen/articles/Article_075.pdf.

- 22.Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK. lordif: An R Package for Detecting Differential Item Functioning Using Iterative Hybrid Ordinal Logistic Regression/Item Response Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations. Journal of statistical software. 2011;39(8):1–30. doi: 10.18637/jss.v039.i08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Narasimhalu K, Lai JS, Cella D. Rapid detection of differential item functioning in assessment of health-related quality of life: The functional assessment of cancer therapy. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:101–114. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bevans KB, Pratawadi R, Tucker C, Riley AW, Forrest CB. A psychometric analysis of internet panel survey data collected from children and youth. (Submitted manuscript) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank R. State Children’s Health Insurance Program- Workshop on Pediatric Health and Health Care Quality Measurement and Information Needs National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. 2010 from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/PediatricQualityMeasures/Russell%20Frank.ashx.

- 26.Gesten F. Measurement: Unify the Tribes! Workshop on Pediatric Health and Health Care Quality Measurement and Information Needs National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. 2010 from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/PediatricQualityMeasures/Gesten.ashx.

- 27.Wadhwa S. Measuring Children’s Health and Health Care- Workshop on Pediatric Health and Health Care Quality Measurement and Information Needs National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. 2010 from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/PediatricQualityMeasures/Sandeep%20Wadhwa_3_23_10.ashx.

- 28.Gruttadaro D. The Family Perspective on Measurement and Information Needs- Workshop on Pediatric Health and Health Care Quality Measurement and Information Needs National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. 2010 from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/PediatricQualityMeasures/Gruttadaro.ashx.