Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Our objective was to compare neurologic, functional, and cognitive stroke outcomes in Mexican Americans (MAs) and non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) using data from a population-based study.

Methods:

Ischemic strokes (2008-2012) were identified from the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) Project. Data were collected from patient or proxy interviews (conducted at baseline and 90 days post-stroke) and medical records. Ethnic differences in neurologic (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), range 0-44, higher scores worse), functional (activities of daily living (ADL)/instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) score, range 1-4, higher scores worse), and cognitive (Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MSE), range 0-100, lower scores worse) outcomes were assessed with Tobit or linear regression adjusted for demographics and clinical factors.

Results:

513, 510, and 415 subjects had complete data for neurologic, functional and cognitive outcomes and covariates, respectively. Median age was 66 (IQR: 57-78); 64% were MA. In MAs, median NIHSS, ADL/IADL and 3MSE score were 3 (IQR: 1-6), 2.5 (IQR: 1.6-3.5) and 88 (IQR: 76-94), respectively. MAs scored 48% worse (95% CI: 23%-78%) on NIHSS, 0.36 points worse (95% CI: 0.16-0.57) on ADL/IADL score, and 3.39 points worse (95% CI: 0.35-6.43) on 3MSE than NHWs after multivariable adjustment.

Conclusions:

MAs scored worse than NHWs on all outcomes after adjustment for confounding factors; differences were only partially explained by ethnic differences in survival. These findings in combination with the increased stroke risk in MAs suggest that the public health burden of stroke in this growing population is substantial.

Keywords: Stroke, ethnicity, outcomes

Introduction

Mexican Americans (MAs), the largest subgroup of Hispanic Americans, have an increased stroke risk compared with non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) but experience less case fatality and longer post-stroke survival.1, 2 The finding of improved survival in MAs may give the false sense that MA stroke is less burdensome than stroke in NHWs, but it is possible that the tradeoff for decreased post-stroke mortality is increased post-stroke disability. Limited data support the hypothesis that Hispanics have poorer stroke outcomes than NHWs,3-10 but these studies were either not focused on MAs specifically,3-9 were limited to specialized populations,4, 6, 7, 9 or did not include younger ages where the greatest ethnic difference in stroke incidence for MAs occurs.10 The objective of this study was to test if MAs have poorer stroke outcomes than NHWs after adjustment for confounding factors in a population-based study. Secondarily, we sought to understand the extent to which any observed ethnic differences in stroke outcomes are attributed to ethnic differences in mortality.

METHODS

Data are from the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) Project, November 2008 through June 2012, for which methods have been published.11-13 Briefly, the BASIC Project is a population-based stroke surveillance study in a bi-ethnic community in south Texas (Nueces County). The population of the County was 340,223 in 2010, with 61% of residents being MA.14 This is a non-immigrant population with most MAs being second and third generation US born citizens limiting loss to follow-up due to return migration to Mexico.

Case ascertainment includes active and passive surveillance. Active surveillance involves identification of cases through daily screening of hospital admission logs, medical wards, and intensive care units. Passive surveillance involves identifying cases by searching hospital and emergency department discharge diagnoses, using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (430-438).15 All possible strokes undergo validation by a stroke neurologist blinded to race-ethnicity and age using source documentation. Only ischemic stroke cases were included using a standard clinical definition.16

Interview and Data Collection Procedures

Stroke patients were invited to participate in a structured, in-person baseline interview and outcome interview conducted approximately 90 days following stroke. If the patient was unable to complete an interview, a proxy interview was completed. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish depending on patient preference. Patients who died prior to the outcome interview were excluded from the primary analysis but included in the secondary analysis which investigated the influence of mortality on ethnic differences in outcome. If an individual had more than one event only the first was included. Patients with race-ethnicity other than MA or NHW were excluded due to small numbers (N=75).

Ninety-day Outcome Measures

Neurological deficits were measured by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) administered by a certified study coordinator. Functional outcome was assessed using scales that measure activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). The ADL scale measures seven basic functional abilities (walking, bathing, grooming, eating, dressing, moving, toileting), and the IADL scale includes 15 questions related to daily functioning. Respondents self-reported level of difficulty performing each ADL/IADL task by themselves with responses including 1 (no difficulty), 2 (some difficultly), 3 (a lot of difficulty), and 4 (can only do with help). Responses were summed for each of the 22 ADL/IADL items and divided by the number of items resulting in an average score ranging from 1-4, in keeping with the original Likert scale for ease of interpretation.17 Global cognitive function was assessed using the Modified Mini-mental State Exam (3MSE),18 with a cut-point of 80 used to classify individuals as having dementia.19 To determine ability to participate in cognitive testing, we administered a series of questions to assess language dysfunction. Patients who failed this screen were excluded from cognitive testing. Mortality was ascertained from the social security death index, Texas Department of Health, and next of kin reports.

Variables

Confounding factors were ascertained from baseline interviews and medical records. Baseline interview data included race-ethnicity using Census-defined categories, marital status, educational attainment, pre-stroke function, and pre-stroke cognitive status. Pre-stroke function was measured by the modified Rankin scale (mRS) ascertained by asking a series of structured questions in reference to the pre-stroke period and categorized as 0-1, 2-3 and ≥4 (higher scores represent worse function). Pre-stroke cognitive status was measured using the validated 16-item Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) completed by an informant who knew the patient well and scored as the average of the individual questions resulting in a scale ranging from 1 to 5 (higher scores represent worse cognitive function).20

Medical record data included age, sex, insurance (yes/no), risk factors (history of stroke/TIA, hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol, smoking, excessive alcohol), comorbidities (myocardial infarction, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, congestive heart failure, Parkinson’s disease, end stage renal disease (ESRD)), body mass index (BMI), initial stroke severity, treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), nursing home residence prior to stroke, and do not resuscitate (DNR) orders written during the hospitalization. A comorbidity index was created by summing the above individual risk factors and comorbidities (range: 0-17). Initial stroke severity was abstracted from the medical record or calculated using previously validated methods.21

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables by ethnicity and differences assessed using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Linear regression was used to obtain age-adjusted ethnic differences for ADL and IADL sub-scores and for individual ADLs/IADLs and items of the NIHSS. Tobit regression was used to assess associations between ethnicity and 90-day outcomes using data from participants with complete data. Tobit regression was used to minimize bias that might result because the primary outcomes are constrained by lower and upper bounds.22 Due to skewness, NIHSS was modeled as natural logarithm of NIHSS plus one. Due to the lack of normality of the residuals for the NIHSS model (violation of assumptions for Tobit model), we employed ordinary linear regression with robust standard errors for this outcome only. Parameter estimates were back transformed to represent the percent difference in NIHSS between ethnic groups. Models were run unadjusted including only ethnicity and then adjusted for pre-specified potential confounders including age, sex, education, insurance status, marital status, nursing home residence before stroke, pre-stroke mRS, pre-stroke IQCODE, initial NIHSS, risk factors, BMI and the comorbidity index. Functional forms of continuous covariates were checked by testing if higher order polynomial terms (e.g., quadratic) were significant. It was determined that age, IQCODE and BMI were appropriately modeled using a linear term and that initial NIHSS required a quadratic term.

To investigate the impact of differential mortality on the associations between ethnicity and the outcomes, we re-estimated outcome models using weights such that patients who completed the 90 day interview but had a low probability of being alive at 90 days received higher weight. Weights were constructed as the ratio of the model-predicted probability of remaining alive at 90 days as predicted by the variables included in the fully adjusted outcome models (see list above), divided by the model-predicted probability of remaining alive at 90 days as predicted by these same factors in addition to DNR status. Weights ranged from 0.27 to 7.1. We constructed 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for all regression coefficients.

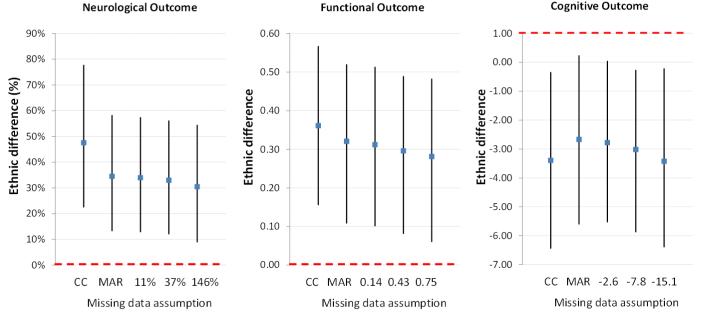

When the likelihood of missing outcomes depends on the outcome itself (e.g., patients with lower cognitive scores could be less likely to complete the outcome interview),23 using data from only complete cases may produce biased results. We conducted sensitivity analyses by modeling the probability of missing outcome values as dependent on the outcome itself.23 We assumed that those missing functional outcome data would have 0, 0.14, 0.43, or 0.75 points higher ADL/IADL scores (higher disability) after adjusting for covariates. Similarly, we assumed that those missing cognitive outcome would have 0, 2.6, 7.8 or 15.1 points lower 3MSE scores, and that those missing NIHSS would have 0%, 11%, 37% or 146% higher NIHSS. Zero difference is equivalent to data missing at random. We used multiple imputation to fill in missing values of covariates under the assumption that covariates were missing at random.

All patients provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan and the local hospitals.

RESULTS

There were 1,198 MA and NHW ischemic stroke patients during the study period, with 842 (70.3%) agreeing to be interviewed. Mortality at 90 days was 14.5% (N=122), resulting in 720 patients eligible for the outcome interview. Of the 720 (461 MA, 259 NHW), fifty-seven patients (7.9%) refused participation in the outcome interview and 69 (9.2%) patients (or their proxies) could not be located for the outcome interview (note 3 of the 69 patients completed the NIHSS but then requested a proxy to complete the the interview but a proxy could not be located). Twenty-four (3.3%), twenty-five (3.5%), and 123 (17.1%) patients had missing or incomplete outcome data for neurologic, functional, and cognitive outcomes, respectively. Thus, of the 720 eligible, 573 (79.6%), 569 (79.0%), and 471 (65.4%), had data for neurologic, functional, and cognitive outcomes, respectively. Due to missing data on covariates, models with complete cases were estimated with sample sizes of 513 (89.5% of 573), 510 (89.6% of 569), and 415 (88.1% of 471) for neurologic, functional, and cognitive outcomes, respectively. Twenty percent of baseline and 21% of outcome interviews were collected from a proxy.

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics by ethnicity for patients with neurologic outcome data (N=573). MAs were younger, had lower educational attainment and were less likely to be treated with tPA, to be a former/current smoker, and to have atrial fibrillation than NHWs. MAs were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, and higher BMI than NHWs. Patients with neurologic outcome data were more likely to be MA, younger, have a higher BMI, and have a lower initial NIHSS and less likely to have a history of stroke/TIA than patients who survived to 90 days but were not included in this analysis (Supplemental Table I).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Ethnicity (N=573). The BASIC Project (November 2008-June2012).

| White (N=204) | MA (N=369) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N or Median |

% or (Q1, Q3) |

N or Median |

% or (Q1, Q3) |

p-value | ||

| Age | 71.5 | (60, 80.5) | 65 | (56, 77) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 107 | 52.5 | 195 | 52.8 | 0.928 | |

| Marital Status | Married/living together | 107 | 52.5 | 185 | 50.1 | 0.565 |

| Single | 9 | 4.4 | 27 | 7.3 | ||

| Widow | 49 | 24.0 | 91 | 24.7 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 39 | 19.1 | 66 | 17.9 | ||

| Education* | < High school | 26 | 12.7 | 184 | 50.0 | <0.001 |

| High school | 65 | 31.9 | 99 | 26.9 | ||

| Vocational/some college | 61 | 29.9 | 50 | 13.6 | ||

| College or more | 52 | 25.5 | 35 | 9.5 | ||

| Insured | 189 | 92.6 | 323 | 87.5 | 0.057 | |

| Nursing home residence | 6 | 4 | 2.0 | 15 | 4.1 | |

| mRS | 0-1 | 97 | 47.5 | 167 | 45.3 | 0.711 |

| 2-3 | 90 | 44.1 | 164 | 44.4 | ||

| 4+ | 17 | 8.3 | 38 | 10.3 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 44 | 21.6 | 35 | 9.5 | <0.001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 55 | 27.0 | 117 | 31.7 | 0.235 | |

| Diabetes | 51 | 25.0 | 213 | 57.7 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 149 | 73.0 | 317 | 85.9 | <0.001 | |

| History of Stroke or TIA | 59 | 28.9 | 112 | 30.4 | 0.720 | |

| Current/former smoker | 92 | 45.1 | 110 | 29.8 | 0.000 | |

| Treated with tPA | 28 | 13.7 | 27 | 7.3 | 0.013 | |

| Initial NIHSS | 4 | (2, 8) | 4 | (2, 8) | 0.756 | |

| IQCODE* | 3.1 | (3, 3.5) | 3.1 | (3, 3.4) | 0.326 | |

| Comorbidity index | 3 | (2, 5) | 3 | (2, 5) | 0.937 | |

| BMI* | 26.6 | (24.2, 31.6) | 29.2 | (25.8, 33.8) | <0.001 | |

MA = Mexican American, NHW = non-Hispanic white, mRS = modified Rankin scale, TIA = transient ischemic attack, tPA = tissue plasminogen activator, NIHSS = National Institute for Health Stroke Scale, IQCODE = Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

IQCODE 10.2% missing; BMI 1% missing; education 0.2% missing

Neurologic Outcome

Twenty percent of eligible MAs (N=416) and 21% of eligible NHWs (N=259) did not have an NIHSS at 90 days. Median NIHSS was 3 (IQR: 1-6) in MAs and 2 (IQR: 0-4) in NHWs. MAs on average scored higher (worse) on all NIHSS elements with the exception of extinction/inattention (Supplemental Table II). A significant age-adjusted ethnic difference was noted for level of consciousness items, visual, motor, language and dysarthria. Among those with complete data (N=513), in unadjusted analysis MAs had a 42% (CI: 18% to 71%) higher NIHSS than NHWs. The ethnic difference persisted and became stronger after multivariable adjustment (48%, CI: 23%, 78%, Table 2). Pre-stroke function, initial NIHSS, and history of stroke/TIA were associated with worse NIHSS at 90 days, while tPA treatment was associated with lower NIHSS at 90 days. Pre-stroke cognitive status (IQCODE) demonstrated a borderline significant association with NIHSS at 90 days.

Table 2.

Results of Multivariable Models of the Association of Ethnicity and Ninety-day Post-Stroke Neurologic, Functional and Cognitive Outcomes. The BASIC Project (November 2008-June2012).

| estimate | NIHSS (n=513) 95% CI |

estimate | Functional outcome (n=510) 95% CI |

estimate | Cognitive outcome (n=415) 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA (versus NHW) | 48% | 23% | 78% | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.57 | −3.39 | −6.43 | −0.35 |

| Age | 14% | −4% | 35% | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.56 | −7.29 | −10.07 | −4.50 |

| Female (versus male) | 0% | −15% | 18% | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.88 | −1.75 | 3.51 |

| Single (versus married) | 22% | −13% | 71% | 0.30 | −0.09 | 0.69 | −1.38 | −7.09 | 4.33 |

| Widowed (versus married) | −6% | −23% | 15% | −0.08 | −0.30 | 0.15 | 1.00 | −2.49 | 4.49 |

| Divorced/separated (versus married) | 6% | −14% | 31% | −0.06 | −0.30 | 0.17 | −0.10 | −3.45 | 3.25 |

| High school education (versus no high school) | −1% | −18% | 21% | −0.15 | −0.36 | 0.07 | 8.33 | 5.13 | 11.53 |

| Vocational/some college (versus no high school) |

−9% | −27% | 14% | 0.00 | −0.25 | 0.25 | 7.49 | 3.86 | 11.12 |

| College or more (versus no high school) | −14% | −32% | 9% | −0.40 | −0.67 | −0.14 | 12.36 | 8.41 | 16.30 |

| Insured | 13% | −14% | 48% | −0.02 | −0.31 | 0.28 | −0.76 | −4.90 | 3.39 |

| Nursing home residence | 26% | −19% | 95% | 0.43 | −0.10 | 0.95 | −16.67 | −29.27 | −4.07 |

| mRS 2-3 (versus 0-1) | 7% | −9% | 25% | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.36 | −1.51 | −4.07 | 1.05 |

| mRS 4-5 (versus 0-1) | 73% | 29% | 134% | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.96 | −2.69 | −9.13 | 3.75 |

| IQCODE | 7% | 0% | 15% | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.17 | −2.68 | −4.02 | −1.35 |

| Comorbidity index | 13% | −11% | 44% | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.67 | −4.60 | −8.55 | −0.65 |

| NIHSS | 67% | 46% | 92% | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.72 | −5.28 | −7.66 | −2.91 |

| NIHSS squared | −1% | −2% | 0% | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.19 |

| BMI | −9% | −17% | 1% | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.39 | −1.18 | 1.97 |

| History of stroke/TIA | 20% | 0% | 45% | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.43 | −1.15 | −4.25 | 1.95 |

| Treated with tPA | −25% | −43% | −3% | −0.40 | −0.69 | −0.11 | 5.67 | 1.12 | 10.23 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | −9% | −24% | 10% | −0.04 | −0.25 | 0.17 | 1.97 | −1.10 | 5.05 |

| Hypertension | 6% | −16% | 34% | −0.08 | −0.33 | 0.18 | 0.67 | −3.04 | 4.38 |

| Coronary artery disease | −1% | −19% | 21% | −0.09 | −0.31 | 0.13 | 4.33 | 0.94 | 7.72 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1% | −21% | 29% | 0.04 | −0.24 | 0.31 | 1.79 | −2.47 | 6.05 |

| Current/former smoker | −1% | −18% | 20% | −0.05 | −0.26 | 0.16 | 0.39 | −2.72 | 3.50 |

MA = Mexican American, NHW = non-Hispanic white, CI = confidence interval, mRS = modified Rankin scale, TIA = transient ischemic attack, tPA = tissue plasminogen activator, NIHSS = National Institute for Health Stroke Scale, IQCODE = Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

Note: Estimates given were derived as the regression coefficients from the models (3MSE and ADL-IADL score) and back transformed coefficient for NIHSS. For continuous predictors, estimated association represents difference in outcome associated with 1 IQR change in predictor (1 IQR: 0.44 for IQCODE, 3 for comorbidity index, 6 for initial NIHSS, 8.1 for BMI, 21 for age).

Functional Outcome

Twenty percent of eligible MAs (N=461) and 23% of eligible NHWs (N=259) did not have functional outcome data at 90 days. Median ADL/IADL score was 2.5 (IQR: 1.6-3.5) in MAs and 2.1 (IQR: 1.2-3.0) in NHWs. MAs on average scored higher (worse) and reported a greater frequency of “can only do with help” (4 on Likert scale) on all ADL/IADLs (Supplemental Table III), with significant age-adjusted ethnic differences noted for all items. Among those with complete data (N=510), the unadjusted ethnic difference (MA versus NHW) in ADL/IADL score was 0.30 (95% CI: 0.08, 0.52). After multivariable adjustment, the ethnic difference became stronger (0.36, 95% CI: 0.16-0.57) and remained statistically significant (Table 2). Age, female sex, pre-stroke function, pre-stroke cognitive status (IQCODE), comorbidity index, initial NIHSS, and history of stroke/TIA were associated with worse ADL/IADL score at 90 days, while tPA treatment was associated with better ADL/IADL score at 90 days.

Cognitive Outcome

Of the subjects eligible for the cognitive testing (N=575), 104 subjects failed the language screen (MA N=78, NHW N=26). In total, 37% of eligible MAs (N=461) and 31% of eligible NHWs (N=259) did not have cognitive outcome data at 90 days. Among those without significant language dysfunction, median 3MSE score was 88 (IQR: 76-94) in MAs and 92 (IQR: 79-96) in NHWS. Thirty-one percent of MAs had post-stroke dementia compared with 25% of NHWs. Among those with complete data (N=415), MAs had on average 1.9 (CI: -1.05, 4.98) points lower (worse) 3MSE scores compared to NHWs in the unadjusted analysis. After multivariable adjustment (Table 2), the ethnic association became stronger and was statistically significant with MAs having on average 3.39 points lower 3MSE scores (CI: 0.35, 6.43). Age, nursing home residence before stroke, pre-stroke cognitive status (IQCODE), comorbidity index, and initial NIHSS were associated with worse 3MSE scores while increasing education, tPA treatment, and CAD were associated with better 3MSE scores.

After re-estimating the outcome models using weights to account for differential post-stroke mortality by ethnicity, ethnic differences in all outcomes were attenuated but statistically significant. MAs had a 39% (CI: 30%, 48%) higher NIHSS, 0.22 (CI: 0.15, 0.30) higher ADL/IADL score, and 2.61 (CI: 1.44, 3.44) points lower 3MSE scores compared to NHWs after accounting for mortality differences.

Ethnic differences were slightly attenuated after accounting for the possibility of bias due to missing data, but remained statistically significant across various assumed strengths of the association between the missing values for the outcomes and the likelihood of missing values (Figure).

Figure.

Ethnic differences (Mexican American versus non-Hispanic White) in (a) NIHSS, (b) ADL/IADL score, and (c) 3MSE score across a range of assumed missing data mechanisms (x-axis of panels: CC=complete case, MAR=missing at random, and three assumed values of the difference in scores that those missing would have after adjusting for covariates).

DISCUSSION

MAs have increased stroke risk but lower case fatality and longer post-stroke survival compared with NHWs. 1, 2, 13 Our current results suggest that this prolonged survival is at the expense of poor outcomes, as MA stroke survivors experienced poorer neurologic, functional and cognitive outcomes than NHWs even after adjustment for a comprehensive list of factors. Differential mortality by ethnicity explained some but not all of the observed ethnic differences in outcomes suggesting that research on the causes of poorer outcomes in MAs compared with NHWs is warranted.

The results of this study provide information on the prognosis of MA stroke survivors. On average at 90 days post-stroke, MAs experience mild neurologic and cognitive impairment, but one-third of MA stroke survivors were classified as having dementia, and MAs experienced more aphasia than NHWs. Levels of functional impairment were more substantial. MAs reported greater difficulty than NHWs with all ADLs and IADLs. Averages for several IADL items were close to or greater than 3 indicating many MAs have difficulty doing these tasks on their own. These findings are of particular importance given that increasing ADL/IADL scores are highly predictive of nursing home admission and the need for informal care.24, 25

Our findings for MAs regarding dependence in specific ADLs/IADLs are similar but somewhat lower (i.e., better function) than those reported for elderly MAs with self-reported stroke in the Hispanic EPESE, possibly due to the younger average age of our MA population. 10 A limited number of studies have reported that Hispanics have poorer functional and cognitive outcomes than NHWs following stroke.3-10 Our results build on these studies by providing data on outcomes from a population-based stroke study specifically focused on MAs, the largest and fastest growing subgroup of Hispanic Americans in the US.

While many studies have measured stroke outcomes in NHWs, comparisons with our results are challenging due to the differing study populations, time frames for outcome assessments and measures used. Our results regarding dependence in specific ADLs for NHWs are similar but slightly lower (i.e., better function) than those reported in stroke survivors from Framingham; potentially due to our NHWs being several years younger on average.26 Comparability of our results for NHWs to those in Framingham suggests that our findings regarding ethnic differences are not likely due to more favorable outcomes in our particular population of NHWs.

Given the rapidly growing MA population, increased stroke risk in this population in combination with prolonged survival and increased disability will result in an escalating number of MA stroke survivors requiring assistance. Studies have shown that MAs are less likely to be admitted to a nursing home suggesting that informal care may be particularly important in this group; however, there is virtually no data available on the informal stroke caregiving experience of MAs.25, 27, 28 This topic should be a target of future research to understand the impact of informal stroke caregiving on both caregivers and patients.

Strengths of this study include the population-based design, the non-immigrant population limiting return migration, comprehensive outcome ascertainment, thorough adjustment for confounding factors, and sensitivity analysis to understand the impact of potential selection bias. There are some limitations that warrant discussion. We did not have data on the psychosocial impacts of stroke, such as depression, or on post-stroke rehabilitation, both of which may impact outcomes and differ by ethnicity.6, 7, 9, 29-31 These factors are important targets for future research. We did not have data on ischemic stroke subtype, although we have previously demonstrated no ethnic differences in stroke subtype in this community suggesting this factor does not explain ethnic differences.32 As in any prospective observational study, there was some loss to follow up and there were differences noted between patients included in our primary analysis and those who were not included with respect to age, ethnicity, history of stroke/TIA, initial stroke severity, and BMI. Importantly, we included these factors in our multivariable models and our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that our results regarding ethnic differences were robust to missing data. Our outcome measures were broad measures of neurologic, functional and cognitive outcomes chosen for their validity and previous use in MAs or Hispanics. Given our findings of ethnic differences in these broad measures future research should aim to unravel the more subtle differences that might be behind these disparities. Our measure of functional outcome was self-reported and thus measurement error is possible. It is possible that our observed ethnic difference in cognitive outcome was due to potential cultural bias in the test or non-cognitive factors.33 Educational attainment is a potent cognitive confounder but was included in our multivariable model. Our data on risk factors were collected from medical records only versus objective measurements which may have resulted in residual confounding by these factors. However, we have previously demonstrated that access to medical care in this community is high in both ethnic groups suggesting there are not large differences in the likelihood of diagnosis,34 although there may be differences in risk factor control that we did not account for in our analysis. Finally, the study is focused on one community in south Texas where the majority of MAs are second and third generation citizens and therefore results may not be generalizable to other populations or to immigrant MAs.

Summary

MA stroke patients experienced moderate functional disability and nearly one-third had post-stroke dementia. In addition, MA stroke patients experienced worse neurologic, functional and cognitive outcomes at 90 days than NHWs. Increased stroke risk, prolonged post-stroke survival, and increased post-stroke disability suggest the future public health burden of stroke in the growing and aging MA population will be staggering.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

Drs. Lisabeth, Sánchez, Smith and Morgenstern are funded by National Institutes of Health R01 NS38916 (grant funding this work).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Lisabeth is funded by National Institutes of Health R01 NS062675, R01 HL098065, and R01 NS070941.

Jonggyu Baek has no disclosures.

Dr. Skolarus has no disclosures.

Nelda Garcia has no disclosures.

Dr. Brown is funded by National Institutes of Health R01 NS062675, R01 HL098065, R01 NS070941.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Risser JM, Uchino K, Garcia N, et al. Excess stroke in Mexican Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:376–383. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisabeth LD, Risser JM, Brown DL, Al-Senani F, Uchino K, Smith MA, et al. Stroke burden in Mexican Americans: The impact of mortality following stroke. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinojosa MS, Rittman M, Hinojosa R, Rodriguez W. Racial/ethnic variation in recovery of motor function in stroke survivors: Role of informal caregivers. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berges IM, Kuo YF, Ottenbacher KJ, Seale GS, Ostir GV. Recovery of functional status after stroke in a tri-ethnic population. Pm R. 2012;4:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen JJ, Washington EL, Aponte-Soto L. Racial disparities in the pathogenesis and outcomes for patients with ischemic stroke. Manag Care Interface. 2004;17:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Uthe CE, Rittman MR. Caregiver mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in stroke: Implications for culturally sensitive interventions. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55:372–382. doi: 10.1037/a0021486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottenbacher KJ, Campbell J, Kuo YF, Deutsch A, Ostir GV, Granger CV. Racial and ethnic differences in postacute rehabilitation outcomes after stroke in the United States. Stroke. 2008;39:1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhamoon MS, Moon YP, Paik MC, Boden-Albala B, Rundek T, Sacco RL, et al. Long-term functional recovery after first ischemic stroke: The Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2009;40:2805–2811. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.549576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiou-Tan FY, Keng MJ, Jr., Graves DE, Chan KT, Rintala DH. Racial/ethnic differences in fim scores and length of stay for underinsured patients undergoing stroke inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:415–423. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000214320.99729.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ontiveros J, Miller TQ, Markides KS, Espino DV. Physical and psychosocial consequences of stroke in elderly Mexican Americans. Ethnicity & disease. 1999;9:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Risser JM, Moye LA, Garcia N, Akiwumi O, Uchino K, et al. Designing multi-ethnic stroke studies: The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:520–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piriyawat P, Smajsova M, Smith MA, Pallegar S, Al-Wabil A, Garcia NM, et al. Comparison of active and passive surveillance for cerebrovascular disease: The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1062–1069. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sanchez BN, Brown DL, Zahuranec DB, Garcia N, et al. Persistent ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in Mexican Americans. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:778–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau State and County Quickfacts Nueces County, Texas. Http://quickfacts.Census.Gov/qfd/states/48/48355.html. Accessed December 19, 2013.

- 15.World Health Organization MONICA Manual, Part IV: Event Registration. Section 3: Event Registration Quality Assurance Methods. 1990 Nov; Http://www.Thl.Fi/publications/monica/manual/part4/iv-3.htm. Accessed December 19, 2013.

- 16.Asplund K, Tuomilehto J, Stegmayr B, Wester PO, Tunstallpedoe H. Diagnostic-criteria and quality-control of the registration of stroke events in the monica project. Acta Med Scand. 1988:26–39. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1988.tb05550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector WD, Fleishman JA. Combining activities of daily living with instrumental activities of daily living to measure functional disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:S46–57. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: The mini mental state exam (MMSE) and modified mini-mental state exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tombaugh TN, McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hubley AM. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and the modified MMSE (3MS): A psychometric comparison and normative data. Psychol Assessment. 1996;8:48–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Development and cross-validation. Psychol Med. 1994;24:145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams LS, Yilmaz EY, Lopez-Yunez Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH stroke scale. Stroke. 2000;31:858–862. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobin JM. Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econometrica. 1958;26:24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Rensbergen G, Pacolet J. Instrumental activities of daily living (i-adl) trigger an urgent request for nursing home admission. Arch Public Health. 2012;70:2. doi: 10.1186/0778-7367-70-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemper P. The use of formal and informal home care by the disabled elderly. Health Serv Res. 1992;27:421–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Wolf PA. Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the framingham heart study. Stroke. 2009;40:1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Houtven CH, Norton EC. Informal care and health care use of older adults. J Health Econ. 2004;23:1159–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss CO, Gonzalez HM, Kabeto MU, Langa KM. Differences in amount of informal care received by non-Hispanic whites and latinos in a nationally representative sample of older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku LJ, Cutchin MP, Heatwole-Shank K, Edwards LJ. Disparities in postacute rehabilitation care for stroke: An analysis of the state inpatient databases. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011;92:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.House A, Knapp P, Bamford J, Vail A. Mortality at 12 and 24 months after stroke may be associated with depressive symptoms at 1 month. Stroke. 2001;32:696–701. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willey JZ, Disla N, Moon YP, Paik MC, Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, et al. Early depressed mood after stroke predicts long-term disability: The northern manhattan stroke study (nomass) Stroke. 2010;41:1896–1900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchino K, Risser JM, Smith MA, Moye LA, Morgenstern LB. Ischemic stroke subtypes among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites: The BASIC project. Neurology. 2004;63:574–576. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133212.99040.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black SA, Espino DV, Mahurin R, Lichtenstein MJ, Hazuda HP, Fabrizio D, et al. The influence of noncognitive factors on the mini-mental state examination in older Mexican-Americans: Findings from the Hispanic epese. Established population for the epidemiologic study of the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith MA, Risser JM, Lisabeth LD, Moye LA, Morgenstern LB. Access to care, acculturation, and risk factors for stroke in Mexican Americans: The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project. Stroke. 2003;34:2671–2675. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000096459.62826.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.