Diseases of the cerebral vasculature contribute to diverse forms of brain dysfunction, injury, and cell death. Small vessel disease (SVD) of the brain accounts for ~25–30% of strokes and is a leading cause of age- and hypertension-related cognitive decline and disability 1. Despite its impact on the brain, there are currently no specific treatments for SVD, and therapeutic options for secondary prevention are particularly limited compared to other common causes of stroke.

Cerebral SVD refers to pathological processes that affect the structure or function of small vessels on the surface and within the brain, including arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules and veins 1. Clinically, the consequences of pathological changes of small vessels of the brain can be detected with neuroimaging. These consequences include white matter hyperintensities, small infarctions or hemorrhages in white and/or deep gray matter, enlargement of perivascular spaces, and brain atrophy 2, 3. SVD can progress silently for many years before becoming clinically evident 2. Hence, medical scientists must not only address the clinical impact of SVD but also identify targets for prevention and early treatment. Both these tasks require a better understanding of the pathogenesis of SVD.

The majority of SVD is sporadic and appears driven by a complex mix of genetic and cardiovascular risk factors, among which age and hypertension are deemed the most important 1, 2. Rare monogenic forms of SVD have been identified and offer excellent opportunities for mechanistic studies using genetic models based on familial disease mutations 4. In some cases, genetic and sporadic forms of SVD may exhibit common underlying mechanisms. This article focuses on Mendelian forms of SVD, excluding the hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathies which have been the subject of recent reviews 5. Particularly, we review the pathogenesis of collagen type IV-related SVD and CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) two archetypal Mendelian SVD, highlighting potential translational implications as we discuss challenges and opportunities for the future.

Small vessels of the brain: Unique functional properties

The human brain, although accounting for only ~2% of the body mass, receives ~20% of cardiac output 6. Blood flow to the brain is conducted through intracranial arteries, which derive mainly from the circle of Willis, through smaller vessels on the brain surface 7. These pial arteries branch extensively into smaller arterioles, which then penetrate into the brain parenchyma and terminate as an extensive capillary network (Figure 1) 7. Penetrating arterioles have relatively few branches and are separated from the parenchyma by the Virchow-Robin space 7. As this space disappears, vessels that continue and pass deeper into the brain are termed parenchymal arterioles. Arterioles, beyond the Virchow-Robin space, and capillaries are encased by endfeet processes of astrocytes 8 although the interactions between astrocytic endfeet and vascular muscle can vary substantially depending on the brain region 9. Blood within postcapillary venules, both parenchymal and pial, is then drained into dural venous sinuses 7. Regional differences in vascular anatomy and local perfusion are prominent. For example, subcortical white matter is supplied by terminal arterioles with limited potential for collateral flow and a lower microvascular density compared to the gray matter 10, 11. Collectively, such differences are thought to make this region particularly vulnerable to reductions in local microvascular pressure (local perfusion pressure), hypoperfusion, and/or ischemia 11.

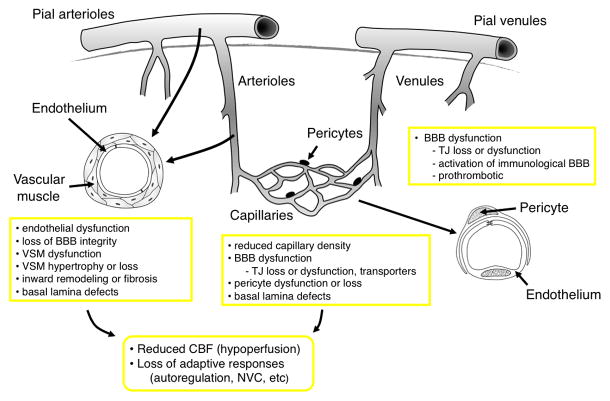

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of key elements of the cerebral microcirculation with the main changes in these segments that can occur during SVD. (VSM, vascular smooth muscle, TJ, tight junctions; NVC, neurovascular coupling; BBB, Blood brain barrier; CBF, cerebral blood flow)

Small vessels of the brain exhibit distinct characteristics 7, 10. First, the brain has little means of energy storage. Mechanisms that regulate these vessels help to ensure that the brain normally receives an adequate supply of blood under a variety of conditions. The primary determinants of resting cerebral blood flow (CBF) include perfusion pressure, autoregulatory mechanisms, and vascular reactivity to the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide 7, 10. Local changes in cellular activity (mostly neurons and glia) modulate CBF above or below this baseline level. Increases in cellular activity normally increase CBF which serves to support enhanced glucose and oxygen demand 11. Our understanding of this phenomenon, known as functional hyperemia or neurovascular coupling, remains an active area of research. Local increases in CBF are induced by dilation of vascular muscle in nearby arteries and arterioles, supported by flow-mediated dilation of upstream vessels, and possibly effects of pericytes on the diameter of capillaries. Both neurons and astrocytes interact closely with vascular cells and thus participate in regulation of local CBF in response to the metabolic needs of surrounding tissue 6, 12, 13. Second, the brain is subjected to wide variations in arterial pressure during daily activity. Another important feature of the cerebral vasculature is its ability to autoregulate and maintain CBF relatively constant over a substantial range of arterial pressures 10. In relation to mechanisms, autoregulation results from the ability of arteries and arterioles to constrict or dilate when intravascular pressure increases or decreases, respectively. Although myogenic reactivity is thought to play a major role in these responses, other mechanisms likely contribute as well in vivo 10, 14. Third, a fundamental feature of the CNS vasculature is reflected by the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) which is largely impermeable to the passive movement of cells, proteins, and most bioactive compounds present in the blood. The BBB consists of endothelial cells, anchored to each other by tight junctions proteins supported by a continuous basement membrane 15. At the level of capillaries, integrity of the BBB is also determined by pericytes, which are tightly apposed to endothelial cells and fully enwrapped by the same basement membrane and perivascular astrocytic endfeet, which cover large domains of these microvessels 15, 16.

Therefore, precise control of CBF to support normal brain homeostasis and function relies on an elaborate and sophisticated ensembly of vascular cells working in concert with neurons and astrocytes. In the most distal segment of the circulation, this complex is often called the neurovascular unit 8. When other portions of the cerebral vasculature are taken into account, terms such as the vascular neural network are sometimes used 17. Considering the complexity of this network, it is not surprising that either structural or functional perturbations of small vessels in brain can have dramatic consequences, including on function and integrity of white matter.

SVD of the brain: Why study rare Mendelian forms?

The vascular-risk-factor approach

Because the greatest risk factors for development of SVD are cardiovascular, previous efforts to elucidate its pathogenesis have relied mainly on “vascular-risk factor-approaches”. Studies in rodents and other models have documented many effects (mostly deleterious) of hypertension on the cerebral vasculature 18, 19. For example, hypertension produces vascular structural and functional changes that are thought to contribute to reductions in resting CBF, impaired vasodilation and vasodilator reserve, and shifts in the autoregulatory curve (to the right) that increases vulnerability of the brain to hypotension 18, 19. Multiple mechanisms likely underlie these changes but angiotensin II, a major therapeutic target in hypertension and other forms of cardiovascular disease, appears to play a central rôle 18. Studies in both people and animals models suggest inter-related oxidant- and immune-dependent mechanisms mediate many of the vascular effects of angiotensin II, with some effects being independent of changes in blood pressure 18–20. However, the direct causal link between these vascular changes and brain lesions, particularly white matter disease and lacunar infarcts, is lacking.

Features of SVD have been described in the microvasculature in mouse models of hypertension including impairment of vasodilator responses (endothelium-dependent and neurovascular coupling), narrowing of the arteriolar lumen (inward remodeling), and increased permeability of the BBB 18, 19. In many of these models, the duration of hypertension has been relatively short. As a consequence, while studies using mouse models of hypertension have provided novel insight into mechanisms responsible for cerebrovascular changes, they have not yet established whether these models can fully recapitulate key elements of SVD including parenchymal injury 21.

More work in this area has been done using rat models, particularly genetic models of hypertension. Studies of the spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rat (SHRSP), which develop cerebral edema and hemorrhage, suggest that disruption of the BBB may be a key mechanism by which hypertension causes white matter lesions. However, although often cited as a model of sporadic SVD, the SHRSP is a model of malignant severe hypertension, with blood pressures that are often well beyond the range of autoregulation and with variable phenotypic outcome depending on the dietary regiment 22. Genetic models with more modest sustained hypertension also develops features of SVD including reduction in microvascular diameter and activation of perivascular microglia but the specific impact of these changes on brain parenchyma is also unclear 23.

Despite being a risk factor for SVD, the relationship between elevated blood pressure and SVD is complex. Like most risk factors for SVD, only a fraction of patients with hypertension develop the disease (and often only with age), and many patients with SVD are normotensive. Furthermore, in addition to the magnitude and the duration of blood pressure elevation, excessive blood pressure variability may contribute to the pathogenesis of SVD 2. Particularly in animal models, the lack of attention to vascular effects of aging, both alone and in the presence of hypertension, may partly explain the difficulty in developing better models of SVD. Hence, studying the pathogenesis of SVD through a vascular-risk factor-lens remains important, but is an approach with challenges requiring further improvement.

The one-mutated gene-at-a-time approach

Familial SVD, largely indistinguishable from sporadic SVD, has been characterized in recent years. Highly penetrant mutations have been identified in five distinct genes including NOTCH3, COL4A1, COL4A2, TREX1 and HTRA1 (Supplementary Table I) 4. Continued identification of related mutations is expected considering recent advances in next-generation sequencing technologies. Although there are no precise figures, it is increasingly appreciated that NOTCH3 and COL41/2 mutations may account for a large proportion of familial SVD whereas TREX1 and HTRA1 mutations are likely very rare 4.

Importantly, a single point mutation in these genes is sufficient to produce a highly penetrant disease meaning that individuals carrying a pathogenic variant have a ~100% risk of developing the disease, nearly independent of the environment. Although rare, these monogenic forms of SVD have immediate relevance to sporadic SVD. For example, the overall clinical and neuroimaging features of CADASIL resemble those of the most common sporadic SVD, except for an earlier age at onset of stroke events and an increased frequency of migraine with aura 24. Moreover, study of these hereditary forms of SVD has provided insight into proteins which play critical roles in the cerebral vasculature. For example, type IV collagen is one of the major components of the basement membrane. Collagen IV is dispensable for deposition and initial assembly of components of the basement membrane during early development but is also required for maintenance of membrane integrity 25. In addition to its structural role, collagen IV participates in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions through integrin and non-integrin receptors that are critically important for cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and differentiation 26. As another example, NOTCH3 is a receptor predominantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle and pericytes that plays a critical role in the maturation and function of small vessels of the brain 27. Finally, technical advances have permitted the generation of predictive relevant mouse models based on familial disease mutations. These approaches include the ability to express the mutated protein product in both temporal- and cell-specific fashion.

In summary, the approach of mutating one-gene-at-a-time has provided significant opportunities to address some of the key scientific in the quest to identify SVD mechanisms including the identification of biological pathways that promote vascular changes, the development of predictive mouse models of SVD, and deciphering the causal link(s) between vascular changes and resulting brain lesions.

Modeling Mendelian SVD in the mouse: A mixed picture

Due to the many technical possibilities that can be used to manipulate its genome, the mouse has become an extremely popular animal model. Despite these advantages, mice also have potential limitations including, relatively small brain and body size, short lifespan, and a lower ratio of white versus gray matter.

COL4A1/2-related SVD: A mouse model with successful translation

In the past, large collections of mutant mice have been produced by genome-wide random chemical mutagenesis using N-ethyl N-nitrosourea (ENU). After treatment with ENU, mice are mated in forward phenotypic and genetic screens designed to uncover abnormal phenotypes and mutations responsible for these phenotypes. With this approach, a variety of mouse lines carrying substitutions of glycine residues in the collagenous domain of the Col4a1 or Col4a2 genes, that play a crucial role in the formation and stabilization of the triple-helical molecule, has been obtained 28. Among these, Col4a1+/Δex41 mice (formerly named Col4a1+/Δex40), which express a mutant collagen alpha-1(IV) chain with a 17 aa inframe deletion because of a mutation in the splice acceptor site of exon 41 (formerly named exon 40), have been the most extensively characterized. At birth, all heterozygous Col4a1+/Δex41 mutant pups have cerebral hemorrhage and about half of them die within a day 29. A small proportion of young adult mice have porencephalic cavities 29. Notably, adult mice also develop spontaneous multifocal recurrent intracerebral hemorrhages, predominantly in the basal ganglia, that can be symptomatic or clinically silent 30. Unfortunately, we are not aware of any pathological data on cerebral white matter. Interestingly, mutant mice also exhibit eye (retinal arterial tortuosity, ocular anterior segment dysgenesis, optic nerve hypoplasia), kidney (microalbuminuria, hematuria) and skeletal muscle abnormalities 28, 30. Electron microscopy has demonstrated basement membrane defects in cerebral vessels as well as in other tissues of the Col4a1 mutant mice, including uneven edges, variable density and thickness, focal disruption, splitting, and herniations 30. Of major importance, all of these clinical and pathological manifestations were subsequently recognized in families with SVD and missense mutations resulting in substitution for one of the invariant glycine residues within the Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeats in the collagenous domain have been identified in affected patients 30, 31. COL4A2 assembles with COL4A1 to form the heterotrimeric triple helix of collagen IV. Recent studies indicate that COL4A2 mutations in humans and mice phenocopy COL4A1 mutations, although with a lesser severity 28.

CADASIL: Incomplete but relevant mouse models

CADASIL is caused by stereotyped missense mutations that alter the number of cysteine residues in the extracellular domain of NOTCH3 (Notch3ECD), leading to pathological accumulation and deposition of Notch3ECD at the plasma membrane of vascular muscle and in extracellular deposits called granular osmiophilic material (GOM) 24. Recent studies suggest that CADASIL mutations produce novel gain of function(s) of mutated protein arising from unique protein–protein interactions rather than a loss of its canonical function 32. Knock-in and transgenic approaches, using smooth muscle-specific promoters or a P1-derived artificial chromosome (PAC) containing the entire Notch3 locus, have been employed to attempt modeling of CADASIL in the mouse. These mice develop two pathological hallmarks of the disease, ie Notch3ECD aggregates or GOM deposits in the brain and peripheral vessels 33. Yet, only increased mutant NOTCH3 levels by a factor of at least four, under the control of the Notch3 promoter (TgPAC-Notch3R169C), results in fully penetrant brain lesions. Specifically, PAC-Notch3R169C transgenic mice exhibit Notch3ECD accumulation and GOM deposits by one and five months of age respectively and, white matter alterations starting at 12 months of age 34. However, these mice have normal lifespan and do not exhibit lacunar infarction. Studies of the CADASIL mouse models suggest that Notch3ECD and GOM deposits are the earliest vascular change, both occurring prior to white matter lesions, which are likewise the earliest brain parenchyma change, a finding which is clinically relevant 33. Indeed, in humans, Notch3ECD aggregates and GOM deposits can be detected in skin vessels of mutation carriers more than a decade before the disease becomes clinically apparent 24. White matter hyperintensities are the earliest detected brain MRI change preceding the onset of symptoms by 10–15 years and have consistently been found in mutation carriers beyond 35 years of age 24.

Why has modeling CADASIL in the mouse been less successful than modeling collagen IV-related SVD? Compared to the latter, CADASIL has a later age of onset and may be driven by a toxic-gain-of function mechanism 32. As anticipated with such a mechanism, prolonged exposure to the mutant protein is assumed to be necessary to trigger cell dysfunction or degeneration. It is thus conceivable that the relatively short life span of mice is limiting. Alternatively, divergent results may reflect fundamentally different mechanisms underlying these two diseases (see below).

Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy and CARASIL

No currently published mouse models stably express RVCL-linked mutations in TREX1. A least two different lines of mice with constitutive inactivation of the HtrA1 gene, which mimics the loss-of-function nature of the CARASIL-associated mutations, have been generated. Reduced capillary density in the retina has been documented in one line 35 and increased trabecular bone mass has been shown in the second 36. However, there is no mention of brain lesions, although it is unclear the extent to which the brain parenchyma and the cerebral vasculature have been analyzed.

Lessons and opportunities from Col4A1-related SVD and CADASIL mouse models

COL4A1/2-related SVD mouse models

In addition to playing a crucial role in the discovery of COL4A1/2 mutations in patients with SVD, Col4a1 mouse models proved valuable in elucidating some important aspects of the disease.

Head trauma and intensive sport exercises have been reported as risk factors of intracerebral hemorrhages 31. Mouse studies have shown that surgical delivery of pups carrying the Col4a1 mutation strongly reduces the occurrence of severe perinatal cerebral hemorrhages, indicating that head trauma, particularly during delivery, is indeed a predisposing factor for cerebral hemorrhages in COL4A1 mutation carriers 30. On the basis of this experimental observation, the follow-up of pregnant women who carry a pathogenic COL4A1 mutation includes repeated ultra-sound evaluation and recommendation for a caesarean delivery. In addition, both the patients and their physicians are informed about the risk of head trauma 31.

Clinical manifestations of COL4A1/2 mutations are extremely variable between and even within affected families, and the age of onset can range from the fetal period to adulthood 28. Mouse studies have pinpointed genetic modifiers as likely contributors to variable expressivity of the disease. Gould and colleagues have shown that the phenotype resulting from Col4a1 mutation varied greatly among mice depending on genetic background. For example, retinal arteriolar tortuosity and ocular anterior segment dysgenesis were highly penetrant in mice with the C57BL/6J background and almost absent in mice with the mixed CAST-BL/6 background 30. Further genetic analyses identified a locus on mouse chromosome 1, which likely contains the modifier gene(s) 37. Allelic heterogeneity may be another source of variability. Notably, mutations clustered within the N-terminus of the collagenous domain of COL4A1 in humans are associated with a preferential phenotypic association, which includes the presence of arterial aneurysms, a high prevalence of eye, kidney, and skeletal manifestations and Raynaud’s phenomenon, to which the term HANAC (Hereditary Angiopathy with Nephropathy, Aneurysms and Cramps)” syndrome has been coined 38. Analysis of new mouse models with HANAC syndrome-associated COL4A1 mutations, under controlled genetic background, may be of interest to test this possibility.

In addition, the existing Col4a1 mouse models offer a unique opportunity to address many unresolved issues in collagen IV-related SVD, namely the exact mechanisms of white matter disease, cerebral hemorrhages, and porencephalic cavities. Although disruption of the vascular basement membrane is likely to compromise vascular integrity, this possibility remains to be tested. Furthermore, based on initial studies of aorta 39, it is likely that these mutations also affect function in small cerebral vessels.

CADASIL mouse models

Analysis of the CADASIL mouse models, particularly of the PAC-Notch3R169C transgenic mouse model that recapitulates the pre-symptomatic stage of the human disease, has dramatically changed our view of the starting point for this disease.

A key initial finding relates to the potential mechanisms of white matter disease in CADASIL. In patients, imaging studies have revealed a decrease in CBF and cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2 or acetazolamide 24. However, reduced CBF was observed in patients with tissue lesions and thus might occur secondary to tissue loss. On the basis of autopsy studies of patients with CADASIL, it has been argued that vasoreactivity might be compromised as a consequence of arterial stiffening or stenosis of small penetrating arteries, particularly in white matter 40. Importantly, in old TgPAC-Notch3R169C mutant mice with diffuse white matter disease, there is neither stenosis nor fibrosis of the arterial wall, additionally, there is no evidence of degeneration of vascular muscle and integrity of the BBB is preserved 34. Instead, in vivo and ex vivo functional analysis have revealed, prior to the appearance of white matter lesions, cerebrovascular dysfunction which includes decreased myogenic responses, impaired autoregulation during hypotension, and attenuated functional hyperemia 34. Moreover, a mild (10–20%) diffuse baseline hypoperfusion has been detected in both the unaffected gray and white matter in the mutant mice 34. Another unexpected finding was the discovery of an age-dependent reduction in brain capillary density in these mice 34. These findings suggest that a key initiating event for development of white matter disease is cerebrovascular dysfunction acting in concert with microcirculatory rarefaction to reduce resting CBF and disrupt diverse vasodilator mechanisms. Accordingly, there is evidence that white matter is highly vulnerable to moderate chronic hypoperfusion 41 and may be more vulnerable to cerebrovascular dysfunction 11.

Another interesting finding pertains to migraine. In CADASIL patients, frequency of migraine with aura is five times higher than in the general population and is usually the first clinical manifestation (average age at onset of 30 years), which may occur in the absence of any neuroimaging abnormalities 24. Cortical spreading depression (CSD), the electrophysiological substrate of migraine aura, has been investigated in a transgenic mouse model (TgSM22α-hNotch3R90C) which develop age-dependent Notch3ECD and GOM deposits but no brain tissue lesions. Notably, TgSM22α-hNotch3R90C mice overexpress a low amount of mutant human NOTCH3 under a smooth muscle specific promoter 33. These mutant mice have a much lower threshold for CSD induction, as well as a higher CSD propagation speed 42. In addition to providing an explanation for the higher frequency of migraine with aura in CADASIL patients, especially at the very beginning of the disease, these results suggest for the first time a causal link between primary brain vascular changes and a CSD phenotype. Such a relationship may be specific to CADASIL since the prevalence of migraine with aura is not increased in sporadic SVD. The observation that CSD susceptibility is unchanged in a mouse model of chronic forebrain hypoperfusion, induced by bilateral common carotid artery stenosis, argues against an involvement of hypoperfusion per se in this phenotype 42. Additional studies are required to determine the precise molecular basis of increased CSD susceptibility.

Challenges and new areas of investigation

Beside the identification of additional molecular players in familial SVD, elucidation of the network of genes/gene products by which NOTCH3, COL4A1/2, HTRA1 and TREX1 mutations drive small vessel pathology is clearly an area that requires further investigation. The finding of impaired transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family signaling in brain vessels of CARASIL patients 43 needs to be further substantiated and a causal link with the vascular defects observed in CARASIL remains to be established. The molecular mechanisms of COL4A1/2 pathogenesis is still controversial, specifically, whether vessel changes are due to collagen IV haploinsufficiency at the basement membrane 44 or intracellular accumulation of misfolded proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum 45. It is unknown whether cellular mislocalization of the mutant TREX1 protein interferes with its function 46. Finally, it is still highly debated whether a reduction in NOTCH3 activity might contribute to the CADASIL disease process 47, 48. However, against the challenges described above, recent studies lend support to a Notch3ECD cascade hypothesis in CADASIL disease pathology, which proposes that aggregation/accumulation of Notch3ECD is a central event, promoting the abnormal recruitment of functionally important extracellular matrix proteins that ultimately cause multifactorial toxicity 32. Given that collagen type IV is a core component of the extracellular matrix of brain vessels and HTRA1, a serine protease secreted into the extracellular matrix of brain vessels (AJ, unpublished), this raises the possibility that alterations in the matrisome (defined as the ensemble of extracellular matrix proteins and associated factors 49) of the cerebral microvasculature, might be a converging pathogenic mechanism underlying several forms of familial SVD.

Genetically engineered mouse models of hereditary SVD are still in their infancy. Mouse models of CARASIL and RCVL need to be developed, and better CADASIL models, which recapitulate the full spectrum of the disease, are also needed. In addition, there are at least two aspects in the characterization of the existing SVD models that have been neglected to this point, namely neuroimaging and cognitive studies, which are instrumental to the definition of markers and consequences of SVD in humans. These are clearly areas that require further effort.

Studies point to a possible loss of normal vascular integrity in the pathogenic effects of collagen type IV mutations, and to early cerebrovascular dysfunction in the pathogenic effects of CADASIL-associated NOTCH3 mutations. Identifying cellular and molecular mechanisms involved offers great promise to develop genetic or pharmacological strategies that could reverse the vascular defects in the existing COLA41 and CADASIL mouse models, and establish the causal link between these vascular alterations and the occurrence of brain tissue lesions. Another question is whether the diversity of tissue lesions (white matter hyperintensities, small infarctions or hemorrhages in the white and/or deep gray matter, visible perivascular spaces and brain atrophy) in SVD reflects a diversity of underlying mechanisms. Interestingly, a recent study showing that the majority of incident lacunes in CADASIL patients develop at the edge of a white matter hyperintensity raises the possibility that the mechanisms of lacunes and white matter hyperintensities are intimately connected in CADASIL 50, and perhaps other pathologies.

The need for treatment for SVD, coupled with the availability of mouse models, is fueling interest in developing targeted therapeutic approaches. At this point, therapeutic opportunities are emerging for CADASIL with the clearance of Notch3ECD aggregates or the reduction of mutant NOTCH3 expression, using for example antisense oligonucleotides.

Finally, several lines of evidence indicate that genetic susceptibility factors contribute to the occurrence of sporadic SVD as part of a multifactorial predisposition 51. There is a growing appreciation that variants in genes that underlie Mendelian diseases may also modulate the risk for complex forms of the same disease 52. A recent study suggests that common variants of the NOTCH3 gene increase the risk of age-related white matter lesions in hypertensive patients 53. Additionally, rare coding variants in the COL4A1 and in the COL4A2 genes, which may affect COL4A1 and COL4A2 secretion, have been identified in a small cohort of patients with sporadic intracerebral hemorrhages 54, 55 These finding thus support the idea that monogenic and common non-Mendelian forms of SVD may have similar molecular underpinnings. Specifically, molecular changes and resulting small vessel pathology that arise in Mendelian SVD as a consequence of a single point mutation may be produced in sporadic SVD by a combination of vascular risk factors and altered expression/function of specific variants of Mendelian SVD-contributing genes.

In closing, the identification of major genetic causes of non-hypertensive adult-onset SVD has provided an important advance in the field of SVD and it is increasingly appreciated that monogenic forms of adult-onset SVD are invaluable paradigms for understanding the pathogenesis of SVD. Further, it is anticipated that one of the next chapters in this field may involve closing the loop between the rare familial SVD and the common sporadic SVD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the French National Research Agency (grant number ANR Genopath 2009-RAE09011HSA) to AJ, from the National Institutes of Health (HL-62984 and HL-113863) and Department of Veterans Affairs (BX001399) to FF, and from the Fondation Leducq (Transatlantic Network of Excellence on the Pathogenesis of Small Vessel Disease of the Brain) to AJ and FF.

References

- 1.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: From pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: Insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483–497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto Y, Craggs L, Baumann M, Kalimo H, Kalaria RN. Review: Molecular genetics and pathology of hereditary small vessel diseases of the brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:94–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Frangione B, Rostagno A, et al. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of sporadic and hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:115–130. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA, Newman EA. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edvinsson L, Krause DN, editors. Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1–521. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iadecola C, Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nn2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ZL, Yao Y, Norris EH, Kruyer A, Jno-Charles O, Akhmerov A, et al. Ablation of astrocytic laminin impairs vascular smooth muscle cell function and leads to hemorrhagic stroke. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:381–395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cipolla MJ. The cerebral circulation. In: Granger DN, Granger J, editors. Integrated systems physiology: From molecule to function. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010. pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. 2013;80:844–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Klett F, Offenhauser N, Dirnagl U, Priller J, Lindauer U. Pericytes in capillaries are contractile in vivo, but arterioles mediate functional hyperemia in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22290–22295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011321108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn KM, Nelson MT. Potassium channels and neurovascular coupling. Circ J. 2010;74:608–616. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei EP, Kontos HA. Increased venous pressure causes myogenic constriction of cerebral arterioles during local hyperoxia. Circ Res. 1984;55:249–252. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang JH, Badaut J, Tang J, Obenaus A, Hartman R, Pearce WJ. The vascular neural network--a new paradigm in stroke pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. The Robert M. Berne distinguished lecture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1566–1582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faraco G, Iadecola C. Hypertension: A harbinger of stroke and dementia. Hypertension. 2013;62:810–817. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Effects of angiotensin II on the cerebral circulation: Role of oxidative stress. Front Physiol. 2012;3:484. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hainsworth AH, Brittain JF, Khatun H. Pre–clinical models of human cerebral small vessel disease: Utility for clinical application. J Neurol Sci. 2012;322:237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey EL, Smith C, Sudlow CL, Wardlaw JM. Is the spontaneously hypertensive stroke prone rat a pertinent model of sub cortical ischemic stroke? A systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:434–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pannozzo MA, Holland PR, Scullion G, Talbot R, Mullins JJ, Horsburgh K. Controlled hypertension induces cerebrovascular and gene alterations in Cyp1a1-Ren2 transgenic rats. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013;7:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, Tournier-Lasserve E, Bousser MG. Cadasil. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:643–653. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poschl E, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, Saito K, Ninomiya Y, Mayer U. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development. 2004;131:1619–1628. doi: 10.1242/dev.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khoshnoodi J, Pedchenko V, Hudson BG. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc Res Tech. 2008;71:357–370. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fouillade C, Monet-Lepretre M, Baron-Menguy C, Joutel A. Notch signalling in smooth muscle cells during development and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:138–146. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo DS, Labelle-Dumais C, Gould DB. COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations and disease: Insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:R97–110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould DB, Phalan FC, Breedveld GJ, van Mil SE, Smith RS, Schimenti JC, et al. Mutations in Col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science. 2005;308:1167–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1109418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould DB, Phalan FC, van Mil SE, Sundberg JP, Vahedi K, Massin P, et al. Role of COL4A1 in small-vessel disease and hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1489–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vahedi K, Alamowitch S. Clinical spectrum of type IV collagen (COL4A1) mutations: A novel genetic multisystem disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:63–68. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834232c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monet-Lepretre M, Haddad I, Baron-Menguy C, Fouillot-Panchal M, Riani M, Domenga-Denier V, et al. Abnormal recruitment of extracellular matrix proteins by excess Notch3ECD: A new pathomechanism in CADASIL. Brain. 2013;136:1830–1845. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joutel A. Pathogenesis of CADASIL: Transgenic and knock-out mice to probe function and dysfunction of the mutated gene, Notch3, in the cerebrovasculature. Bioessays. 2011;33:73–80. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joutel A, Monet-Lepretre M, Gosele C, Baron-Menguy C, Hammes A, Schmidt S, et al. Cerebrovascular dysfunction and microcirculation rarefaction precede white matter lesions in a mouse genetic model of cerebral ischemic small vessel disease. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:433–445. doi: 10.1172/JCI39733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Lim SL, Du H, Zhang M, Kozak I, Hannum G, et al. High temperature requirement factor A1 (HTRA1) gene regulates angiogenesis through transforming growth factor-β family member growth differentiation factor 6. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1520–1526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.275990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham JR, Chamberland A, Lin Q, Li XJ, Dai D, Zeng W, et al. Serine protease HTRA1 antagonizes transforming growth factor-β signaling by cleaving its receptors and loss of HTRA1 in vivo enhances bone formation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould DB, Marchant JK, Savinova OV, Smith RS, John SW. Col4a1 mutation causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and genetically modifiable ocular dysgenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:798–807. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plaisier E, Gribouval O, Alamowitch S, Mougenot B, Prost C, Verpont MC, et al. COL4A1 mutations and hereditary angiopathy, nephropathy, aneurysms, and muscle cramps. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2687–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Agtmael T, Bailey MA, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Craigie E, Jackson IJ, Brownstein DG, et al. Col4a1 mutation in mice causes defects in vascular function and low blood pressure associated with reduced red blood cell volume. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalimo H, Ruchoux MM, Viitanen M, Kalaria RN. Cadasil: A common form of hereditary arteriopathy causing brain infarcts and dementia. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:371–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata M, Ohtani R, Ihara M, Tomimoto H. White matter lesions and glial activation in a novel mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2004;35:2598–2603. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143725.19053.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eikermann-Haerter K, Yuzawa I, Dilekoz E, Joutel A, Moskowitz MA, Ayata C. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy syndrome mutations increase susceptibility to spreading depression. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:413–418. doi: 10.1002/ana.22281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hara K, Shiga A, Fukutake T, Nozaki H, Miyashita A, Yokoseki A, et al. Association of HTRA1 mutations and familial ischemic cerebral small-vessel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1729–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemmens R, Maugeri A, Niessen HW, Goris A, Tousseyn T, Demaerel P, et al. Novel COL4A1 mutations cause cerebral small vessel disease by haploinsufficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:391–397. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray LS, Lu Y, Taggart A, Van Regemorter N, Vilain C, Abramowicz M, et al. Chemical chaperone treatment reduces intracellular accumulation of mutant collagen IV and ameliorates the cellular phenotype of a COL4A2 mutation that causes haemorrhagic stroke. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:283–292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards A, van den Maagdenberg AM, Jen JC, Kavanagh D, Bertram P, Spitzer D, et al. C-terminal truncations in human 3'-5' DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause autosomal dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1068–1070. doi: 10.1038/ng2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Manent J, Lee JH, Tikka S, Ospina C, Vanderburg CR, et al. Hypomorphic Notch 3 alleles link Notch signaling to ischemic cerebral small-vessel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E128–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101964108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rutten JW, Boon EM, Liem MK, Dauwerse JG, Pont MJ, Vollebregt E, et al. Hypomorphic NOTCH3 alleles do not cause CADASIL in humans. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:1486–1489. doi: 10.1002/humu.22432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naba A, Clauser KR, Hoersch S, Liu H, Carr SA, Hynes RO. The matrisome: In silico definition and in vivo characterization by proteomics of normal and tumor extracellular matrices. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111 014647. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duering M, Csanadi E, Gesierich B, Jouvent E, Herve D, Seiler S, et al. Incident lacunes preferentially localize to the edge of white matter hyperintensities: Insights into the pathophysiology of cerebral small vessel disease. Brain. 2013;136:2717–2726. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dichgans M. Genetics of ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:149–161. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antonarakis SE, Chakravarti A, Cohen JC, Hardy J. Mendelian disorders and multifactorial traits: The big divide or one for all? Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nrg2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt H, Zeginigg M, Wiltgen M, Freudenberger P, Petrovic K, Cavalieri M, et al. Genetic variants of the NOTCH3 gene in the elderly and magnetic resonance imaging correlates of age-related cerebral small vessel disease. Brain. 2011;134:3384–3397. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weng YC, Sonni A, Labelle-Dumais C, de Leau M, Kauffman WB, Jeanne M, et al. COL4A1 mutations in patients with sporadic late-onset intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:470–477. doi: 10.1002/ana.22682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeanne M, Labelle-Dumais C, Jorgensen J, Kauffman WB, Mancini GM, Favor J, et al. COL4A2 mutations impair COL4A1 and COL4A2 secretion and cause hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.