Abstract

There is increasing evidence for activation of developmental transcriptional regulatory pathways in heart valve disease. Here we review molecular regulatory mechanisms involved in heart valve progenitor development, leaflet morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix organization that also are active in diseased aortic valves. These include regulators of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transitions, such as the Notch pathway effector RBPJ, and the valve progenitor markers Twist1, Msx1/2, and Sox9. Little is known of the potential reparative or pathological functions of these developmental mechanisms in adult aortic valves, but it is tempting to speculate that valve progenitor cells could contribute to repair in the context of disease. Likewise, loss of either RBPJ or Sox9 leads to aortic valve calcification in mice, supporting a potential therapeutic role in prevention of disease. During aortic valve calcification, transcriptional regulators of osteogenic development are activated in addition to valve progenitor regulatory programs. Specifically, the transcription factor Runx2 and its downstream target genes are induced in calcified valves. Runx2 and osteogenic genes also are induced with vascular calcification, but activation of valve progenitor markers and the cellular context of expression are likely to be different for valve and vascular calcification. Additional research is necessary to determine if developmental mechanisms contribute to valve repair or if these pathways can be harnessed for new treatments of heart valve disease.

Keywords: Heart valve development, transcription factor, bicuspid aortic valve, calcific aortic valve disease

Introduction

Heart valve disease, most commonly aortic valve stenosis, is prevalent in the aged population with >2% of the population over 65 being affected.1 The current standard of care is surgical replacement, and there are no pharmacologically based treatments in use clinically.2 The molecular and cellular processes that contribute to aortic valve stenosis are not fully characterized, but could provide insights into the development of new therapeutic approaches. There is increasing evidence that regulatory pathways that control heart valve development also are active with valve pathogenesis later in life. Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) includes activation of valve interstitial cells (VICs), as well as increased expression of transcription factors that regulate the earliest events of valvulogenesis in the developing embryo.3 In addition to valve developmental pathways, regulatory proteins that promote the development of cartilage and bone lineages also are active in diseased valves.4, 5 Thus knowledge of the molecular regulatory pathways that control valve development will likely be informative in determining the molecular mechanisms of valve pathogenesis. In addition, abnormal valve development before birth can lead to increased or accelerated valve disease later in life. The majority of aortic valves that are replaced due to stenosis are congenitally malformed with an abnormal number of leaflets, usually bicuspid rather than tricuspid aortic valves.6 In addition, these abnormal valves require replacement at an earlier age than normal tricuspid aortic valves.6 Here we review transcriptional regulatory pathways that control heart valve development and their contributions and implications for heart valve disease, specifically CAVD.

Overview of heart valve development

During embryogenesis, heart valve development begins with the formation of endocardial cushions in the outflow tract (OFT) and atrioventricular canal (AVC) of the primitive heart tube (Figure 1). The molecular and cellular mechanisms of endocardial cushion formation are conserved in birds and mammals and begin at embryonic day 9–10 in mice and E31–35 in humans.5 The endocardial cushions consist of endocardial endothelial cells that undergo an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), giving rise to mesenchymal valve progenitor cells that reside in a hyaluronan-rich extracellular matrix. Valvulogenesis continues with elongation and thinning of the endocardial cushions to form valve primordia of the semilunar and AV valves. During fetal and postnatal stages, the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the valve leaflets continues to remodel and compartmentalize into the collagen-rich fibrosa, proteoglycan-rich spongiosa, and elastin-rich atrialis/ventricularis layers.7, 8 The ECM composition and organization of the valve leaflets are critical for normal valve function, and dysregulation of ECM remodeling or structural components can lead to valve malformations or pathogenesis which may be apparent soon after birth or later in life.9, 10

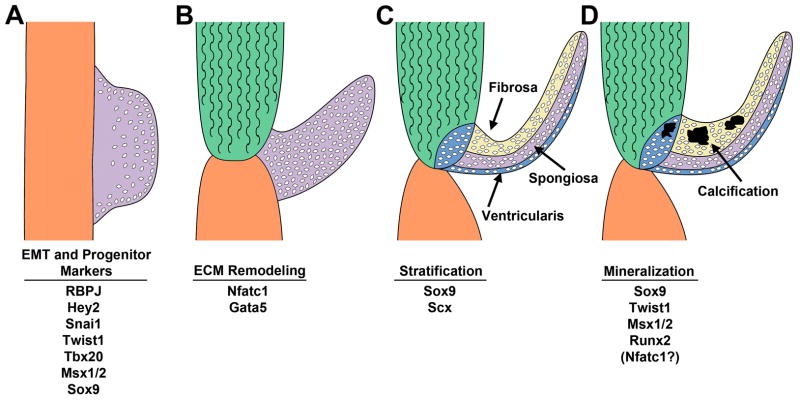

Figure 1. Transcription factors active in aortic valve development and disease.

A. Endocardial cushions (purple) form in the cardiac outflow tract and atrioventricular canal. Valve progenitor cells are generated by an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and express indicated transcription factors. B. Endocardial cushions elongate to form valve primordia of individual valve leaflets. Extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and morphogenesis of the valve leaflets is dependent on Nfatc1 and Gata5. C. The ECM of the semilunar valve primordia stratifies into fibrosa, spongiosa, and ventricularis layers associated with Sox9 and Scx expression. D. Calcific aortic valve disease is characterized by expression of transcription factors involved in valve development and osteogenesis. Please see text for details and citations.

Cells from multiple embryonic origins contribute to mature semilunar and AV valve leaflets as determined by Cre-based cell lineage studies in mice.5 The predominant source of interstitial cells in all four mature valves is the endothelial layer-derived endocardial cushion cells, as indicated by Tie2-Cre lineage tracing.11, 12 In adult semilunar valves, neural crest-derived cells, marked with Wnt1-Cre, are present and preferentially localize in the leaflets adjacent to the aorticopulmonary septum.13 Recent studies using Wilms’ tumor 1 (Wt1)-Cre demonstrate the presence of epicardial-derived cells in the parietal, but not septal, leaflets of the AV valves.14 Additional bone marrow-derived cells have been reported to be present in aortic valve leaflets during development and after birth.15, 16 There is increasing evidence for diversity in cellular origins of individual valve leaflets during development and in adults. Currently it is not known if these subpopulations have distinct functions in normal valve homeostasis or have specific roles in valve pathogenesis.

Transcriptional regulation in endocardial cushions and valve progenitor cells

The gene regulatory network of valve progenitor cells in the endocardial cushions includes several transcription factors involved in EMT and mesenchymal progenitor populations in other organ systems, including bone and cartilage lineages in the developing skeleton.5 Endocardial cushion EMT requires Notch signaling acting through the transcription factor RBPJ, which activates expression of the zinc finger transcription factor Snai1.17 Snai1 is a transcriptional repressor of VE-cadherin (Cdh5), and loss of endothelial cell junctions is required for the transition to a mesenchymal phenotype. Proliferative and migratory mesenchymal cells populate the endocardial cushions (EC) with undifferentiated valve progenitor cells. Transcription factors expressed in the mesenchymal valve progenitors include the bHLH transcription factor Twist1, the T-box factor Tbx20, Sry factor Sox9, and homeodomain proteins Msx1 and 2.18 Twist1 is expressed in endocardial cushion mesenchyme, where it promotes cell migration and proliferation, but is downregulated during later stages of valve leaflet remodeling.19, 20 Direct targets of Twist1 in the developing valves include Tbx20 and Collagen2A1, as well as additional genes involved in cell proliferation and migration.20, 21 Sox9 and Tbx20 also are required for endocardial cushion cell proliferation and expansion of the valve progenitor population.22–24 Strikingly, Twist1, Sox9, and Msx1/2 are expressed in pediatric and adult diseased aortic valves, but their functions and cellular context in valve disease initiation, or potentially repair, have not been defined.3, 20 It is possible that these factors are indicative of the generation of new progenitors by EMT in diseased valves, but this has not yet been demonstrated in vivo. Further study is necessary to determine the roles of valve progenitor gene regulatory networks in disease and to identify new therapeutic strategies based on developmental mechanisms.

Valve leaflet morphogenesis and ECM stratification/remodeling

Valve leaflet morphogenesis includes the elongation and thinning of endocardial cushions accompanied by remodeling and stratification of the ECM. Endocardial cushion mesenchymal cells are highly proliferative, but proliferation is subsequently reduced during leaflet elongation, and VICs remain relatively quiescent in the mature valve leaflets.7, 8 The reduction of endocardial cushion proliferation coincides with the expression of mature ECM proteins, including elastin and fibrillar collagen. The transition from endocardial cushion to remodeling valve leaflet is regulated by the transcription factor Nfatc1. Loss of Nfatc1 in mice leads to embryonic death at midgestation with apparent heart valve remodeling defects.25, 26 Nfatc1 is expressed in endocardial cushion endothelial cells where it promotes cell proliferation and limits EMT in response to VEGF signaling.27, 28 In the elongating valve primordia, Nfatc1, regulated by RANKL signaling, activates expression of cathepsin K and promotes ECM remodeling.27 Additional transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that control ECM remodeling enzyme gene expression or VIC cell cycle withdrawal are relatively undefined.

The ECM compartments of the stratified leaflets share conserved regulatory mechanisms with other connective tissue cell lineages.10 The spongiosa layer is composed predominantly of proteoglycans, and loss of Sox9, a transcription factor required for cartilage development, leads to decreased proteoglycan expression in the remodeling valves.22 Scleraxis (Scx), a bHLH protein required for tendon development, also is expressed in remodeling chordae tendinae of the AV valves, and loss of scleraxis leads to valve remodeling defects and myxomatous phenotypes in adult animals.29, 30 Upstream regulators and downstream targets of these transcription factors defined in cartilage and tendon lineages also are active in the developing valves. In avian valve progenitor cultures, BMP2 treatment promotes Sox9 expression and target gene Aggrecan (Acan) induction, whereas FGF4 treatment promotes Scx expression and tenascin gene induction.29 Osteogenic transcription factors, such as Runx2, are not active in normal developing valves, although they are induced with CAVD.4, 5 Thus the study of cardiac valve ECM regulatory mechanisms has been greatly facilitated by knowledge obtained from cartilage, tendon and bone lineages.

Regulation of semilunar valve leaflet number and morphogenesis

Congenital malformations of the aortic valve, predominantly bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), are the most common congenital heart malformations, occurring with a frequency of approximately 1–2% of live births.31 There is surprisingly little known of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that control the formation of individual semilunar valve leaflets from endocardial cushions after septation of the cardiac outflow tract in the embryo. The Notch signaling pathway is important in this process since mutations in the Notch1 receptor are associated with human BAV.32 However mice heterozygous for Notch1 or the downstream transcription factor RBPJ do not have a significant incidence of BAV.33 Notch1 and RBPJ are required for EMT during endocardial cushion formation, thus BAV could result from abnormalities present at the earliest stages of heart valve development.17 It is possible that other Notch receptors contribute to valve leaflet formation but these regulatory interactions have not been fully defined.

Mutations in the zinc finger transcription factor GATA5 also have been identified in patients with BAV, and mice with heterozygous loss of Gata5 have BAV with incomplete penetrance.34, 35 The heterogeneity of valve malformations in Gata5 heterozygous mice makes it difficult to determine the developmental anomalies that lead to BAV, but defects in endocardial cushion formation were noted in these animals.35 The paucity of mouse models with BAV at high frequency has limited our understanding of the late stages of semilunar valve morphogenesis and leaflet number determination.

Developmental transcription factors in calcific aortic valve disease

Many transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of heart valve development also are active in diseased aortic valves. In addition to being critical for endocardial cushion EMT and valve leaflet formation, Notch signaling has a direct role in aortic valve calcification.32 Adult mice with heterozygous loss of Notch1 or RBPJ fed a high fat diet exhibit aortic valve calcification at several months of age.33 Likewise adult mice with endothelial deletion of the Notch ligand Jag1 exhibit valve calcification late in life.36 The Notch pathway downstream transcription factor Hairy and enhancer of split-related (Hesr)-2/Hey2 can directly repress osteogenic gene induction by the transcription factor Runx2.32 Similarly, loss of Hey2 in mice leads to aortic valve stenosis and osteogenic gene induction, supporting a direct regulatory role for Notch pathway transcriptional effectors in inhibiting adult valve calcification.37 Together, these studies support an inhibitory role for Notch signaling and its downstream transcriptional effectors in aortic valve calcification. Sox9, required for cartilage lineage development, also has been implicated as a protective factor in CAVD. Mice heterozygous for Sox9 in Col2a1-expressing lineages exhibit aortic valve calcification, and ectopic expression of Sox9 can inhibit valve leaflet mineralization and osteogenic gene induction.22, 38 Sox9 expression is increased in pediatric diseased aortic valves that are not calcified and also in adult calcified aortic valves; thus its roles in the initiation and progression of human aortic valve disease are not fully known.3 Msx2 is similarly expressed in human diseased valves and is sufficient to induce vascular calcification though induction of Wnt signaling,3, 39 but its role in aortic valve calcification has not been defined. Nfatc1 also has been reported to be expressed in calcified aortic valves, and the RANKL antagonist osteoprotegerin (OPG) inhibits aortic valve calcification in hypercholesterolemic mice.40, 41 Osteogenic genes, including Runx2 and its downstream targets osteocalcin (Bglap) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), also are expressed in CAVD, but the regulatory mechanisms by which they are induced have not been fully defined.4, 42 Thus, it is becoming increasingly clear that many developmental pathways are active in adult valve disease. However the pathologic or reparative functions of these regulatory mechanisms are not known and their therapeutic potential is yet to be exploited.

Future directions and clinical perspectives

Much remains to be determined regarding the cellular and molecular mechanisms of aortic valve disease. While developmental pathways are clearly activated, the cells that express valve progenitor gene regulatory networks or the mechanisms by which these pathways are activated remain unknown. It has been proposed that new valve progenitors arise by induction of EMT in adult valves, but this has not yet been demonstrated in the context of disease in vivo.43 Activation of resident VICs has been studied extensively as an underlying mechanism of disease, but the origins of cells expressing valve progenitor markers in diseased aortic valves has not yet been determined.44 Likewise, collagen remodeling occurs with development of the fibrosa layer of the valve leaflets and also is increased with aortic valve disease, but the relationship between valve fibrosis and mineralization is not completely clear.10, 45 Infiltrating mesenchymal stem cells and immune cells also have been detected in diseased aortic valves, but their specific contributions to valve thickening or mineralization are not currently known.16, 44 Together, there has been extensive progress made in identifying molecular and cellular processes active in valve disease. However specific pathogenic or reparative functions are less well-defined.

Molecular mechanisms of aortic valve and vascular calcification both include activation of osteogenic factors, such as Runx2.42, 46 However, the cell types involved are likely to be different in that smooth muscle cells, not present in aortic valve leaflets, are predominant in vascular calcification, and inflammation has a significant role in vascular calcification that may not be fully recapitulated in aortic valve disease. In addition, activation of valve developmental regulatory programs, while apparent in CAVD, has not been reported for vascular calcification. Thus, the therapeutic approaches effective for preventing vascular calcification may not effective in treating CAVD. This has already been demonstrated for statin therapies, in wide use for atherosclerosis, that have not been successful in inhibiting or preventing the progression of CAVD in clinical trials.47 Therefore the development of effective therapies for CAVD may need to take into account molecular mechanisms or cellular contributions unique to aortic valve development or pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Transcription factors in heart valve development and disease

| Transcription factor | Role in Development | Role in Disease | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twist1a | ECCb prolif, migration | Active in CAVD | Tbx20, Cdh11, Col2a1 |

| Msx2 | EMT, proliferation | Active in CAVD | none identified |

| Snai1 | EMT | Unknown | Cdh5 |

| RBPJ | EMT | Loss leads to CAVD | Snai1, Hey1, Hey2 |

| Hey2 | EMT | Inhibits Runx2 | Bglap (osteocalcin) |

| Sox9 | Prolif, PG expression | Inhibits CAVD | Col2a1, Acan, Hapln1 |

| Nfatc1 | ECC growth, remodeling | Reported in CAVD | CtsK |

| Gata5 | ECC growth | Loss linked to BAV | Nos3 |

| Runx2 | not present | Osteogenesis | Bglap, ALP |

Please see text for details and citations.

Abbreviations: ECC=endocardial cushion; CAVD=calcific aortic valve disease; EMT=endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; PG=proteoglycan; BAV=Bicuspid Aortic Valve.

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present members of the Yutzey lab for their contributions to this research and M. Vicky Gomez for critical reading of the manuscript.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI R01 HL082716, HL094319, HL114682 to K.E.Y. and F32 HL110390 to E.E.W.

Abbreviations

- AV

atrioventricular

- BAV

bicuspid aortic valve

- CAVD

calcific aortic valve disease

- EC

endocardial cushion

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- VIC

valve interstitial cell

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wirrig EE, Hinton RB, Yutzey KE. Differential expression of cartilage and bone-related proteins in pediatric and adult diseased aortic valves. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajamannan NM, Subramaniam M, Rickard DJ, Stock SR, Donovan J, Springett M, Orszulak T, Fullerton DA, Tajik AJ, Bonow RO, Spelsberg TC. Human aortic valve calcification is associated with an osteoblast phenotype. Circulation. 2003;107:2181–2184. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070591.21548.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combs MD, Yutzey KE. Heart valve development: Regulatory networks in development and disease. Circ Res. 2009;105:408–421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts WC, Ko JM. Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005;111:920–925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155623.48408.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinton RB, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, Yutzey KE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ Res. 2006;98:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Farber M, Mendelson K, Padera RF, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ. Human semilunar cardiac valve remodeling by activated cells from fetus to adult. Circulation. 2006;113:1344–1352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoen FJ. Evolving concepts of cardiac valve dynamics. Circulation. 2008;118:1864–1880. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinton RB, Yutzey KE. Heart valve structure and function in development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:29–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.deLange FJ, Moorman AFM, Anderson RH, Manner J, Soufan AT, deGier-deVries C, Schneider MD, Webb S, Van Den Hoff MJ, Christoffels VM. Lineage and morphogenetic analysis of the cardiac valves. Circ Res. 2004;95:645–654. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141429.13560.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lincoln J, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Development of heart valve leaflets and supporting apparatus in chicken and mouse embryos. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:239–250. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T, Colbert MC, Robbins J. Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res. 2006;98:1547–1554. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wessels A, van den Hoff MJ, Adamo RF, Phelps AL, Lockhart MM, Sauls K, Briggs LE, Norris RA, van Wijk B, Perez-Pomares JM, Dettman RW, Burch JB. Epicardially derived fibroblasts preferentially contribute to the parietal leaflets of the atrioventricular valves in the murine heart. Dev Biol. 2012;366:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visconti RP, Ebihara Y, LaRue AC, Fleming PA, McQuinn TC, Masuya M, Minamiguchi H, Markwald RR, Ogawa M, Drake CJ. An in vivo analysis of hematopoietic stem cell potential: Hematopoietic origin of cardiac valve interstitial cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:690–696. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207384.81818.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajdu Z, Romeo SJ, Fleming PA, Markwald RR, Visconti RP, Drake CJ. Recruitment of bone marrow-derived valve interstitial cells is a normal homeostatic process. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertran E, Perez-Pomares JM, Diez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, delaPompa JL. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakraborty S, Combs MD, Yutzey KE. Transcriptional regulation of heart valve progenitor cells. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9616-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Twist1 function in endocardial cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation during heart valve development. Dev Biol. 2008;317:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakraborty S, Wirrig EE, Hinton RB, Merrill WH, Spicer DB, Yutzey KE. Twist1 promotes heart valve cell proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression during development in vivo and is expressed in human diseased aortic valves. Dev Biol. 2010;347:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MP, Yutzey KE. Twist1 directly regulated genes that promote cell proliferation and migration in developing heart valves. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln J, Kist R, Scherer G, Yutzey KE. Sox9 is required for precursor cell expansion and extracellular matrix gene expression. Dev Biol. 2007;302:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 regulation of endocardial cushion cell proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression. Dev Biol. 2007;302:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X, Zhang W, Hu J, Zhang L, Sultana N, Wu B, Cai W, Zhou B, Cai C-L. Tbx20 acts upstream of wnt signaling to regulate endocardial cushion formation and valve remodeling during mouse cardiogenesis. Development. 2013;140:3176–3187. doi: 10.1242/dev.092502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de la Pompa JL, Timmerman LA, Takimoto H, Yoshida H, Elia AJ, Samper E, Potter J, Wakeham A, Marengere L, Langille BL, Crabtree GR, Mak TW. Role of nf-atc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature. 1998;392:182–186. doi: 10.1038/32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranger AM, Grusby MJ, Gravallese EM, de la Brousse FC, Hoey T, Mickanin C, Baldwin HS, Glimcher LH. The transcription factor nf-atc is essential for cardiac valve formation. Nature. 1998;392:186–190. doi: 10.1038/32426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Combs MD, Yutzey KE. Vegf and rankl regulation of nfatc1 in heart valve development. Circ Res. 2009;105:565–574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu B, Wang Y, Lui W, Langworthy M, Tompkins KL, Hatzopoulos AK, Baldwin HS, Zhou B. Nfatc1 coordinates valve endocardial cell lineage development required for heart valve formation. Circ Res. 2011;109:183–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lincoln J, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Bmp and fgf regulatory pathways control cell lineage diversification of heart valve precursor cells. Dev Biol. 2006;292:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levay AK, Peacock JD, Lu Y, Koch M, Hinton RB, Kadler KE, Lincoln J. Scleraxis is required for cell lineage differentiation and extracellular matrix remodeling during murine heart formation in vivo. Circ Res. 2008;103:948–956. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cripe L, Andelfinger G, Martin LJ, Shooner K, Benson DW. Bicuspid aortic valve is heritable. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg V, Muth AN, Ransom JF, Schluterman MK, Barnes R, King IN, Grossfeld PD, Srivastava D. Mutations in notch1 cause aortic valve disease. Nature. 2005;437:270–274. doi: 10.1038/nature03940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nus M, MacGrogan D, Martinez-Poveda B, Benito Y, Casanova JC, Fernandez-Aviles F, Bermejo J, de la Pompa JL. Diet-induced aortic valve disease in mice haploinsufficient for the notch pathway effector rbpjk/csl. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1580–1588. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padang R, Bagnall RD, Richmond DR, Bannon PG, Semsarian C. Rare non-synonymous variations in the transcriptional activation domains of gata5 in bicupid aortic valve disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:277–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laforest B, Andelfinger G, Nemer M. Loss of gata5 in mice leads to bicuspid aortic valve. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2876–2887. doi: 10.1172/JCI44555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofmann JJ, Briot A, Enciso J, Zovein AC, Ren S, Zhang ZW, Radtke F, Simons M, Wang Y, Iruela-Arispe ML. Endothelial deletion of murine jag1 leads to valve calcification and congenital heart defects associated with alagille syndrome. Development. 2012;139:4449–4460. doi: 10.1242/dev.084871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kokubo H, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Nakashima Y, Kume T, Yoshizumi M, Nakanishi T, Saga Y. Hesr2 knockout mice develop aortic valve disease with advancing age. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:e84–92. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peacock JD, Levay AK, Gillaspie DB, Tao G, Lincoln J. Reduced sox9 function promotes heart valve calcification phenotypes in vivo. Circ Res. 2010;106:712–719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao J-S, Cheng S-L, Pingsterhaus JM, Charlton-Kachigian N, Leowy AP, Towler DA. Msx2 promotes cardiovascular calcification by activating paracrine wnt signals. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1210–1220. doi: 10.1172/JCI24140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexopoulos A, Bravou V, Peroukides S, Kaklamanis L, Varakis J, Alexopoulos D, Papadaki H. Bone regulatory factors nfatc1 and osterix in human calcific aortic valves. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss RM, Lund DD, Chu Y, Brooks RM, Zimmerman KA, El Accaoui R, Davis MK, Hajj GP, Zimmerman MB, Heistad DD. Osteoprotegerin inhibits aortic valve calcification and preserves valve function in hypercholesterolemic mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wirrig EE, Yutzey KE. Developmental pathways in cavd. In: Aikawa E, editor. Calcific aortic vavle disease. Croatia: InTech; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balachandran K, Alford PW, Wylie-Sears J, Goss JA, Bischoff J, Aikawa E, Levine RA, Parker KK. Cyclic strain induces dual-mode endothelial-mesenchymal transformation of the cardiac valve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19943–19948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106954108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajamannan NM, Evans FJ, Aikawa E, Grande-Allen KJ, Demer LL, Heistad DD, Simmons CA, Masters KS, Mathieu P, O’Brien KD, Schoen FJ, Towler DA, Yoganathan AP, Otto CM. Calcific aortic valve disease: Not simply a degenerative process. Circulation. 2011;124:1783–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss RM, Miller JD, Heistad DD. Fibrocalcific aortic valve disease: Opportunity to understand disease mechanisms using mouse models. Circ Res. 2013;113:209–222. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bostrom K, Rajamannan NM, Towler DA. The regulation of valvular and vascular sclerosis by osteogenic morphogens. Circ Res. 2011;109:564–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermans H, Herijgers P, Holvoet P, Verbeken E, Meuris B, Flameng W, Herregods M-C. Statins for calcific aortic valve stenosis:Into oblivion after saltire and seas? Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:284–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]