Abstract

Background and purpose

A decrease of 15% in femoral offset (FO) has been reported to generate a weakness of the abductor muscle, but this has not been directly linked to an alteration of gait. Our hypothesis was that this 15% decrease in FO may also generate a clinically detectable alteration in the gait.

Patients and methods

We performed a prospective comparative study on 28 patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) for unilateral primary osteoarthritis. The 3D hip anatomy was analyzed preoperatively and postoperatively. 3 groups were defined according to the alteration in FO following surgery: a minimum decrease of 15% (9 patients), restored (14), and a minimum increase of 15% (5). A gait analysis was performed at 1-year follow-up using an ambulatory device. Each limb was compared to the contralateral healthy limb.

Results

In contrast to the “restored” group and the “increased” group, in the “decreased” group there was a statistically significant asymmetry between sides, with reduced range of motion and a lower maximal swing speed on the operated side.

Interpretation

A decrease in FO of 15% or more after THA leads to an alteration in the gait. We recommend 3-D preoperative planning because the FO may be underestimated by up to 20% on radiographs and it may therefore not be restored, with clinical consequences.

The femoral offset (FO) and limb length have to be restored during total hip arthroplasty (THA) in order to improve the functional outcomes and to reduce the risk of limping, dislocation (McGrory et al. 1995, Downing et al. 2001, Bourne and Rorabeck 2002, Asayama et al. 2005, Kiyama et al. 2010), and edge loading (Sariali et al. 2010). The restoration of the FO also appears to be crucial to improve the long-term survival rates of THA. Sakalkale et al. (2001) reported that restoration of the FO reduces the wear in THA.

With respect to the functional outcomes of THA, a decrease of 15% in FO has been reported to generate weakness of the abductor muscle (Asayama et al. 2005), but this has not been directly linked to an alteration of gait. Indeed, this threshold was defined under laboratory conditions using a CYBEX machine, which does not correspond to realistic activities of daily living. Our hypothesis was that a 15% decrease in the FO may also generate a clinically detectable alteration of gait.

Many devices are available for analysis of gait, but most of them are constraining and cannot be used without laboratory conditions (Lamontagne et al. 2011). Some authors have proposed the use of devices for ambulatory gait analysis that can be used for long distances and under realistic daily living conditions (Aminian et al. 2004). For example, the Physilog device (Aminian et al. 2004) has been validated as an evaluation tool for the clinical assessment of patients before and after THA.

We analyzed the consequences of an alteration in FO after THA for gait under realistic walking conditions.

Patients and methods

To assess the functional consequences of an alteration in FO, we performed a prospective non-randomized comparative study from May 2006 through May 2009. The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients graded as type A according to Charnley’s classification and who underwent unilateral THA for a unilateral primary osteoarthritis; (2) a minimal alteration in the 3-D value of the FO of 15%, as measured on the preoperative CT-scan; and (3) a signed consent from the patient to use previous medical data for research purposes. The exclusion criteria were: (1) the presence of an arthroplasty or of an associated pathology on the contralateral limb or the same limb; (2) a spine disease; or (3) a non-restoration of the other hip anatomy parameters (center of rotation, limb length). In order to only select patients with an isolated alteration in FO, the 3-D hip anatomy was analyzed preoperatively and postoperatively with CT-scans using Hip-Plan software (Sariali et al. 2009a).

During the inclusion period, 485 consecutive patients underwent THA using an anatomical cementless modular-neck stem (SPS-Modular; Symbios, Switzerland). 3-D preoperative planning was performed routinely in order to analyze the 3-D anatomy of the hip, to choose the best-fitting implants to restore the hip anatomy including the hip rotation center, the FO, and the lower limb length (Sariali et al. 2009a). A low-dose CT-scan (Huppertz et al. 2011) was performed in all the patients 6 weeks after surgery in order to compare the final anatomy to that planned. Spiral CT included the pelvis from the iliac crest to the femoral isthmus. 6 CT slices were also performed on the knee in order to obtain the bicondylar plane reference for the femoral anteversion measurements. A mode combining tube current modulation and low tube voltage was used to reduce the radiation dose. The CT-scan was performed instead of plain radiography at the 6-week and 3-month follow-up, which gave the same final total radiation dose. Indeed, the low-dose protocol corresponded to 4 mSv, which would be equivalent to 2 hip radiographic assessments (AP pelvic view, AP and lateral hip views) (Huppertz et al. 2011).

All the patients were assessed clinically, preoperatively, and at the 1-year follow-up with 4 clinical scores: the Postel Merle d’Aubigné score (PMA), the Harris hip score (HHS), the WOMAC score (Bellamy et al. 1988), and the HOOS (Nilsdotter et al. 2003).

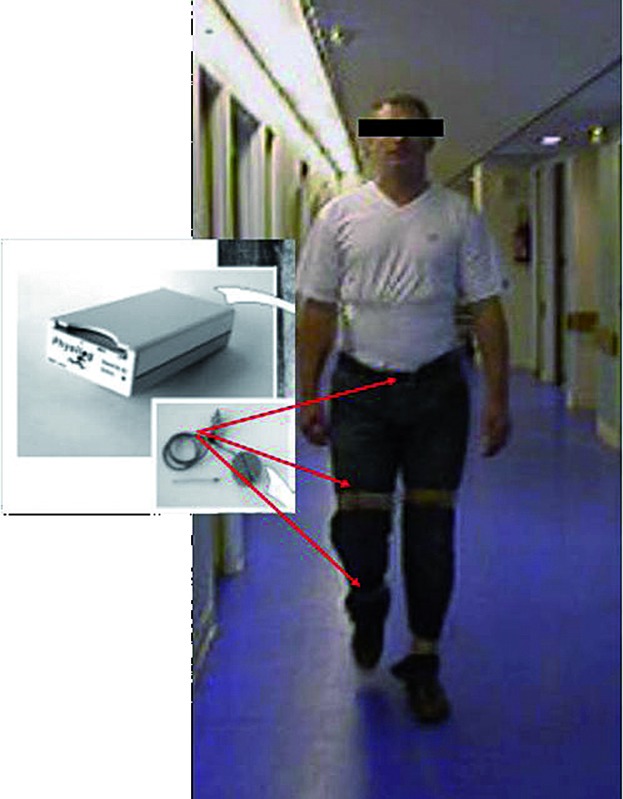

A gait analysis was performed at the 1-year follow-up using the ambulatory device Physilog (BioAGM, Switzerland) (Aminian et al. 2004), which consists of miniature kinematic sensors (gyroscopes) attached to body segments and a portable recorder placed on the waist belt. This setup offers a practical method for gait analysis under daily living conditions. For the present study, 5 miniature gyroscopes (Murata ENC-03J, Murata Manufacturing Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) were attached, 1 to the pelvis, 1 to each shank, and 1 to each thigh (Figure 1). The signals were digitized (12-bit) at a sampling rate of 200 Hz by the portable data logger, and stored for offline analysis. A validated algorithm (Aminian et al. 2004) was used in order to compute the values of spatial and temporal gait parameters from the angular velocity of the lower limbs. This gait analysis technique has been clinically validated for accuracy and reproducibility, by comparing it to a reference motion analyzer (ELITE system; BTS SrL, Milan, Italy) equipped with video cameras (Aminian et al. 2004). Physilog has also been validated as a clinical evaluation tool for patients before and after THA (Aminian et al. 2004).

Figure 1.

A subject carrying the Physilog system. The data logger (weighing 300 g) can be fixed around the waist. Sensors (gyroscopes) are attached by elastic strips to each shank and thigh, and also to the pelvis, and connected to the data logger by a thin cable.

During the study, the patients were asked to walk at their normal speed for 60 meters in the same corridor. For all patients, each limb was compared to the healthy contralateral limb. 3 parameters were analyzed during the exercise: the flexion-extension range of motion of the hip and the knee, and the angular swing speed of the lower limb.

The study was conducted according to the French bioethics law (Article L. 1121-1 of law no. 2004-806, August 9, 2004), and approval was obtained from the special patient protection committee responsible for the hospital.

The cohort

In the 485 consecutive patients, the FO was altered in 59 cases (increased in 21 cases and decreased in 38 patients). Only 14 patients (11 women) met the inclusion criteria: 9 with a decreased FO and 5 with an increased FO. Mean age was 68 (46–83) years and mean BMI was 25 (19–33).

The patients included were matched for age, sex, BMI, and etiology with 14 patients (mean age 67 years (54–78), 11 women) from the same cohort who had a restored FO and who met the other inclusion and exclusion criteria. The 3 groups were comparable regarding age, sex, BMI, and clinical scores before surgery (Tables 1 and 2). In the “decreased” FO group, the average decrease was 18% (15–25), corresponding to 7.6 (6–12) mm (Table 3).

Table 1.

Epidemiologic characteristics of the three groups

| Group | Age Mean [SD] (range) |

BMI Mean [SD] (range) |

Sex ratio M/F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased | 65.6 [10.7] (46–77) | 24.7 [4.9] (19–33) | 2/7 |

| Restored | 67.3 [8.2] (54–78) | 25.5 [3.3] (21–34) | 3/11 |

| Increased | 72.4 [8.9] (61–83) | 27.7 [4.4] (21–33) | 1/4 |

Table 2.

The clinical scores in the groups before surgery and at 1 year follow up: Harris hip score (HHS), Postel Merle d’Aubigné (PMA), WOMAC, HOOS. Values are mean [SD] and (range)

| Group | HHS |

PMA |

WOMAC |

HOOS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 1-year FU | Before | 1-year FU | Before | 1-year FU | Before | 1-year FU | |

| Decreased | 46.6 [21.1] | 87.9 [12.9] | 10.7 [2.1] | 16.3 [1.7] | 53.0 [8.1] | 7.4 [9.0] | 36.5 [11.0] | 86.2 [12.0] |

| (12–87) | (69–100) | (8–15) | (14–18) | (43–69) | (0–28) | (23–52) | (64–100) | |

| Restored | 36.6 [8.3] | 92.4 [6.1] | 10.6 [1.2] | 16.8 [0.9] | 54.0 [8.6] | 8.2 [11.8] | 33.1 [7.6] | 90.9 [8.8] |

| (29–53) | (79–100) | (9–13) | (15–18) | (34–65) | (0–37) | (18–45) | (70–99) | |

| Increased | 34.3 [7.3] | 92.7 [5.1] | 9.4 [0.9] | 16.8 [1.3] | 54.4 [17.2] | 4.0 [2.5] | 29.0 [11.8] | 94.2 [6.3] |

| (27–47) | (88–100) | (8–10) | (15–18) | (35–73) | (0–6) | (20–45) | (85–99) | |

Table 3.

Femoral offset alteration in the three groups

| Group | Femoral offset alteration |

|

|---|---|---|

| (%) Mean [SD] (range) |

(mm) Mean [SD] (range) |

|

| Decreased | -17.9 [3.1] (-25 to -15) | -7.6 [1.8] (-12 to -6) |

| Restored | 0.7 [1.4] (0–4) | 0.3 [0.7] (0–2) |

| Average | 18.1 [1.4] (15–22) | 6.0 [0.7] (5–7) |

Statistics

The Wilcoxon paired signed-ranked test was used to compare the operated hip measurements and the contralateral hip measurements. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata software v.10.0.

Results

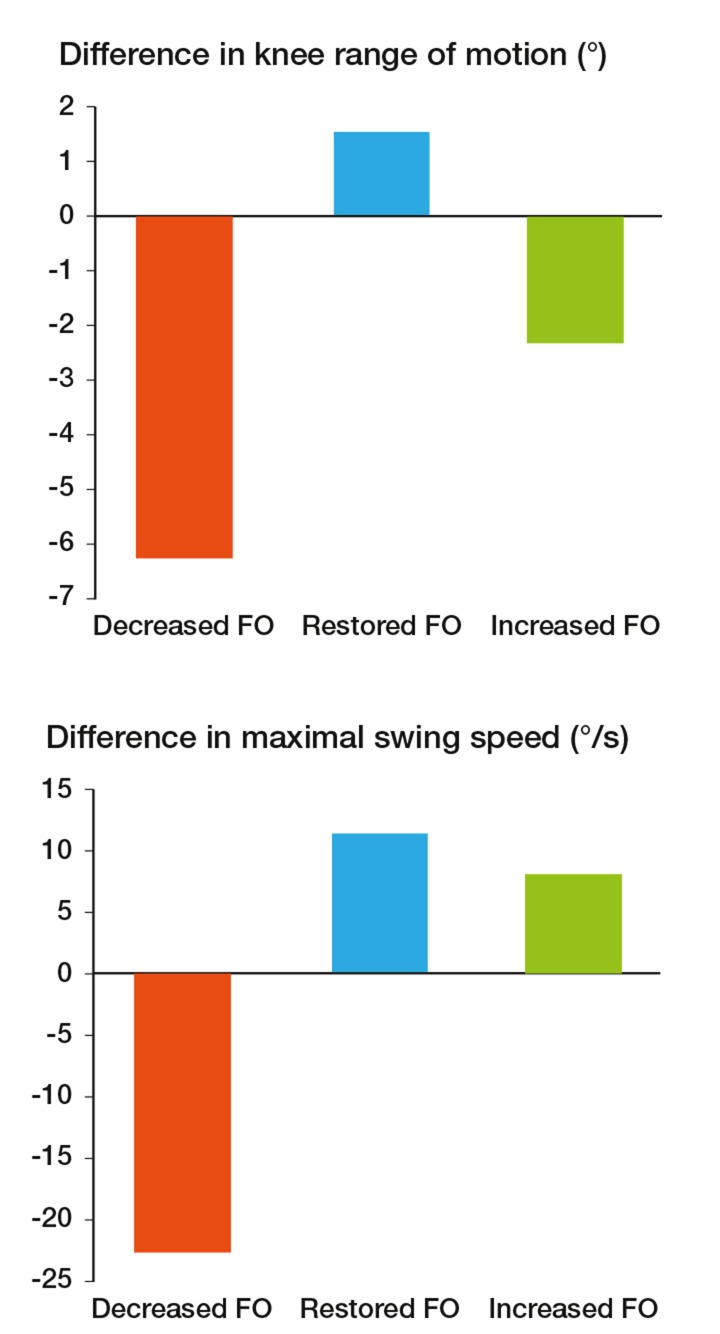

In contrast to the “restored” group and the “increased” group, in the “decreased” group there was a significant asymmetry between the operated limb and the healthy limb. There was reduced range of motion at the knee (–6°; p = 0.004) and a lower maximal swing speed (22°/s; p = 0.01) in the operated limb than in the healthy limb. In contrast, in the “restored” group and the “increased” group, there was no significant alteration in gait on the replaced side (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Difference in knee range of motion and maximal swing speed between the operated side and the healthy limb. In contrast to the 2 other groups, in the “decreased” group there was a statistically significant decrease in the knee range of motion and the maximal swing speed during the gait cycle.

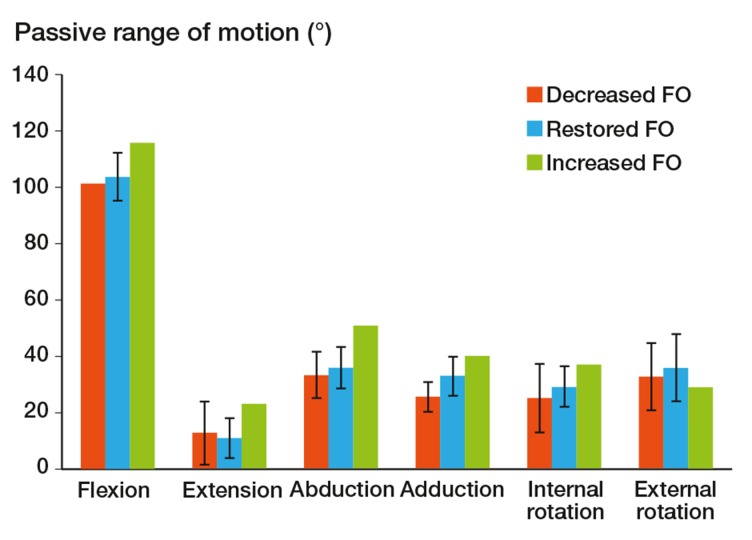

At the 1-year follow-up, all the patients had improved clinically with a similar statistically significant increase in all clinical scores (Table 2). Clinically, there was a decrease in passive hip adduction in the “decreased” FO group (7°; p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Passive range of motion in the 3 groups. Compared to the “restored” FO group, there was a significant decrease in adduction mobility in the “decreased” FO group.

Discussion

Our main finding was that an isolated decrease in FO after THA generated an alteration of the gait with a lower swing speed and a reduced range of motion at the knee when walking. We not found any previous studies that have analyzed the effect of alteration of the FO on the quality of gait.

The clinical scores were similar between the 3 groups. This suggests a shortcoming in the discriminative ability of these scores to detect clinically relevant changes (Crowninshield et al. 2006). Indeed, frequently used clinical scores such as the HHS have ceiling effects, which means that several patients obtain the highest possible score, so that they “reach the ceiling” (Wamper et al 2010).

Our results compare well with the study by Asayama et al. (2005). However, these authors did not analyze gait, and their measurements were performed with a CYBEX machine, which does not correspond to realistic daily living conditions. McGrory et al. (1995) also reported similar results, but they did not analyze the gait. Our findings are also supported by results recently published by Cassidy et al. (2012). These authors analyzed pain and function (with SF12 and WOMAC) in 263 patients who underwent THA, and when using 5 mm as a threshold of precision for the restoration of FO, they showed that an FO that is not fully restored leads to reduced function whereas having an increased FO did not affect either postoperative pain or function. However, they did not analyze alterations in the other hip anatomy parameters—including leg length and the center of rotation—thus making their conclusions weaker.

The present study had some limitations. Firstly, the gait was analyzed exclusively in the sagittal plane, so the abduction/adduction and external/internal rotation motions were not assessed. Secondly, only the kinematics was analyzed; the forces and the moments were not determined because an ambulatory device was used with a long walking distance and not under laboratory conditions. Thus, the use of a force platform was not technically feasible. However, the ambulatory device that we used allowed performance of a kinematic analysis under more realistic conditions corresponding to activities of daily living. Soon we will perform a 3-D analysis of the gait in the same groups in order to obtain more information, especially regarding the forces. However these measurements can only be performed indoors under laboratory conditions and only for small walking distances; thus, the results would be less clinically relevant. Thirdly, a limited number of patients were included (from 14 of 485 consecutive THAs), because of the exclusion criteria—which were strict. However, this strict methodology allowed selection of only patients with an isolated alteration in FO, which gave more strength to the conclusions. Finally, based on the literature review, a threshold of 15% was used in order to include the patients with a clinically relevant alteration in FO. Given the fact that a minimal value was used, a threshold of FO alteration cannot be determined. Ideally, all 485 patients should have undergone a gait assessment and a regression analysis could have been used to determine a threshold for clinically significant FO modification that would generate a gait alteration. Such a study was not technically feasible in our department because of the large number of patients that would be involved. This is why we decided to concentrate directly on the patients with an altered FO.

On the other hand, this study had some strengths. Firstly, a 3-D assessment of the FO was performed, thus avoiding the errors that result from the use of plain radiographs. Sariali et al. (2009b) reported that FO was underestimated when measured on radiographs—by 3.5 mm and up to 13 mm. Secondly, all our patients were free of associated diseases, and FO was the only hip anatomy parameter that was modified. Thirdly, each patient was compared to herself/himself using the healthy contralateral limb as a reference, thus avoiding the bias introduced by the selection of a control group. Finally, the gait was analyzed with an ambulatory device under more realistic conditions than those used in a typical gait analysis laboratory. Patients walked for a long distance and no specific constraints were imposed on them.

Modular-neck stems have been proposed to accurately restore the FO. However, there are no guidelines regarding the precision required for the restoration of FO. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, there is no reported precision threshold value for the FO to guide surgeons at the time of preoperative planning. A minimum of 6 mm of FO alteration which we found to have clinical consequences may thus be proposed as a maximum tolerable alteration in FO after THA. When considering a tolerable range for the change in FO, compromises can be made and the need for modular-neck stems can be reduced.

Given the alteration in FO that corresponded to a gait alteration in the “decreased” group (6–12 mm), the accuracy for the preoperative planning of FO should ideally be about ± 3 mm. According to the literature, 2 techniques appear to achieve such high accuracy: navigation (Kitada et al. 2011) and preoperative 3-D computerized planning (Sariali et al. 2009a, 2012a) . The 3-D preoperative planning using Hip-Plan software has been reported to be highly accurate in helping to restore FO and leg length, with an accuracy of about 1.3 mm (SD 2.6), which is twice as high as that for conventional radiographic templating (Sariali et al. 2012a). This accuracy is achieved because 3-D planning accurately anticipates the final position of the stem relative to the femur, including the final stem anteversion. Indeed, the final FO depends not only on the stem design but also on its final position inside the femur, including anteversion.

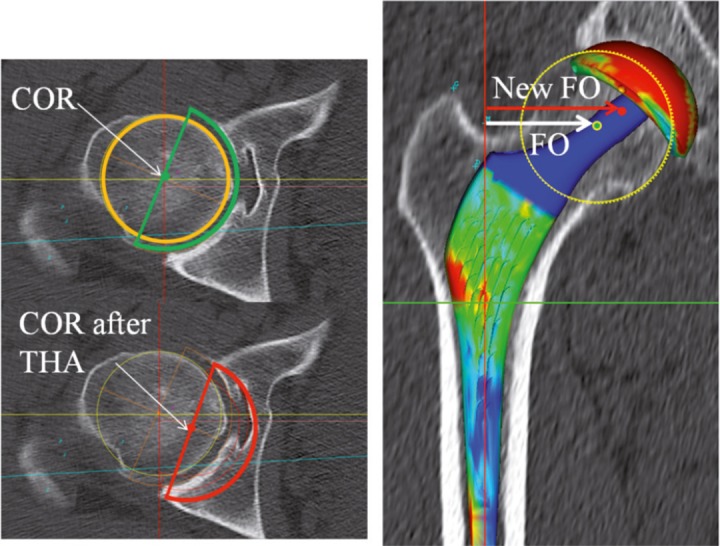

We did not find any alteration in gait in the “increased” group. This finding compares well with results reported by Cassidy et al. (2012). However, this statement should be viewed with caution, as some authors have reported that an increased FO may generate trochanteric pain (Iorio et al. 2006, Sayed-Noor and Sjoden 2006) and higher wear (Girard et al. 2006). The objective should be to normalize the FO, which may however be modified according to the acetabular anatomy. In some cases such as acetabular dysplasia, the center of rotation (COR) has to be shifted medially in order to achieve good mechanical stability for the acetabular cup and to avoid a psoas impingement. In these cases, we propose to increase the FO in order to compensate for the medial-lateral laxity generated by the medial shift of the COR (Sariali et al. 2012b) and therefore to reduce the risk of dislocation (Figure 4). Thus, the final objective should be to restore the global offset, which corresponds to the sum of the FO and the acetabular offset.

Figure 4.

In some cases of dysplastic acetabula, the center of rotation has to be shifted medially. The FO may be increased in order to compensate for the decrease in acetabular offset and to avoid instability.

Conclusion

A 6- to 12-mm decrease in FO after THA may alter the gait, which may not be detected by the usual clinical scores. We recommend the use of 3-D preoperative planning for accurate FO assessment and restoration.

Acknowledgments

ES planned the study, analyzed the results, wrote the manuscript and revised the final version. SK performed the statistical analyses and took part in the results analysis. AM took part in the planning of the study and the achievement of the gait analysis. HPM took part in revising the manuscript.

We thank Dr Nadia Boukhelifa (INRIA Paris, France) for her invaluable help in revising the manuscript and improving the grammar

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aminian K, Trevisan C, Najafi B, et al. Evaluation of an ambulatory system for gait analysis in hip osteoarthritis and after total hip replacement . Gait Posture. 2004;20:1, 102–7. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(03)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama I, Chamnongkich S, Simpson K, et al. Reconstructed hip joint position and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy N, Buchanan W, Goldsmith C. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee . J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne R, Rorabeck C. Soft tissue balancing: The hip . J Arthroplasty (Suppl 1) 2002;4:17–22. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.33263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy K, Noticewala M, Macaulay W, et al. Effet of femoral offset on pain and function after total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2012 Jul 16; doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowninshield R, Rosenberg A, Sporer S. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement . Clin Orthop. 2006;443:266–72. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000188066.01833.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing N, Clark D, Hutchinson J, et al. Hip abductor strength following total hip arthroplasty: a prospective comparison of the posterior and lateral approach in 100 patients . Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:3, 215–20. doi: 10.1080/00016470152846501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard J, Vendittoli P, Roy A, et al. Femoral offset restoration and clinical function after total hip arthroplasty and surface replacement of the hip: A randomized study. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2006;94:4, 376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.rco.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz A, Radmer S, Asbach P, et al. Computed tomography for preoperative planning in minimal invasive total hip arthroplasty: Radiation exposure and cost analysis . Eur J Radiology. 2011;78:3, 406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio R, Healy W, Warren P. Lateral trochanteric pain following primary total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:233. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada M, Nakamura N, Iwana D, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of computed tomography-based navigation for femoral stem orientation and leg length discrepancy . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:5, 674–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyama T, Naito M, Shinoda T, et al. Hip Abductor strengths after total hip arthroplasty via the lateral and posterolateral approaches . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne M, Beaulieu M, Beaule P. Comparison of joint mechanics of both lower limbs of THA patients with healthy participants during stair ascent and descent . J Orth Res. 2011;29:3, 305–11. doi: 10.1002/jor.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrory B, Morrey B, Cahalan T, et al. Effect of femoral offset on range of motion and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77:6, 865–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsdotter A, Lohmander L, Klässbo M, et al. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS) – validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2003;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakalkale D, Sharkey P, Eng K, et al. Effect of femoral component offset on polyethylene wear in total hip arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2001;388:125–34. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200107000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, et al. Accuracy of reconstruction of the hip using computerised three-dimensional pre-operative planning and a cementless modular-neck stem . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009a;91:3, 333–40. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, et al. Three dimensionnal hip anatomy in osteoarthritis. Analysis of the femoral off-set . J Arthroplasty. 2009b;24:6, 990–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Stewart T, Jin Z, et al. Three-dimensional modeling of in vitro hip kinematics under micro-separation regime for ceramic on ceramic total hip prosthesis: an analysis of vibration and noise . J Biomech. 2010;43:2, 326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Mauprivez R, Khiami F, et al. Accuracy of the preoperative planning for cementless total hip arthroplasty. A randomised comparison between three-dimensional computerised planning and conventional templating . Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012a;98:2, 151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Klouche S, Mamoudy P. Investigation into three dimensional hip anatomy in anterior dislocation after THA. Influence of the position of the hip rotation centre . Clin Biomech. 2012b;27:6, 562–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed-Noor A, Sjoden G. Greater trochanteric pain after total hip arthroplasty: the incidence, clinical outcome and associated factors . Hip Int. 2006;16:202. doi: 10.1177/112070000601600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamper K, Sierevelt I, Poolman R, et al. The Harris hip score: Do ceiling effects limit its usefulness in orthopedics? . Acta Orthop. 2010;81:6, 703–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.537808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]