Abstract

Background and purpose

To our knowledge, there is no evidence to support the use of local infiltration analgesia (LIA) for postoperative pain relief after periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). We investigated the effect of wound infiltration with a long-acting local anesthetic (ropivacaine) for postoperative analgesia after PAO.

Patients and methods

We performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00815503) in 53 patients undergoing PAO to evaluate the effect of local anesthetic infiltration on postoperative pain and on postoperative opioid consumption. All subjects received intraoperative infiltration followed by 5 postoperative injections in 10-hour intervals through a multi-holed catheter placed at the surgical site. 26 patients received ropivacaine and 27 received saline. The intervention period was 2 days and the observational period was 4 days. All subjects received patient-controlled opioid analgesia without any restrictions on the total daily dose. Pain was assessed at specific postoperative time points and the daily opioid usage was registered.

Results

Infiltration with 75 mL (150 mg) of ropivacaine did not reduce postoperative pain or opioid requirements during the first 4 days.

Interpretation

The clinical importance of ropivacaine as single component in postoperative treatment of pain is questionable, and we are planning further studies to explore the potential of LIA in larger volume—and also a multimodal regimen—to treat pain in this category of patients.

In some patients, periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is associated with a substantial need for pain treatment. Psoas block, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps, and continuous epidural and spinal analgesia are commonly used but can be associated with side effects such as nausea, drowsiness, and urinary retention (Choi et al. 2003).

Repeated or continuous topical administration of local anesthesia is effective in reducing postoperative pain after hip and knee arthroplasties (Bianconi et al. 2003, Kerr and Kohan 2008) with low incidence of adverse events, and without the motor side effects associated with continuous nerve block techniques. To our knowledge, there is no evidence to support the use of local anesthetic infiltration for postoperative pain relief after PAO. We performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind study to investigate the effect of wound infiltration with a long-acting local anesthetic (ropivacaine) for postoperative analgesia after PAO. Our primary hypothesis was that repeated infiltration with ropivacaine would reduce pain and reduce the requirement for postoperative PCA after PAO for the treatment of hip dysplasia.

Patients and methods

The study was approved by the the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark and the Danish Medicines Agency (Copenhagen, Denmark), and was reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00815503) and it was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the principles of Good Clinical Practice.

Calculation of sample size was based on an expected clinically relevant difference of 10 mg oxycodone in 1 day. From observations in a related study, we estimated SD to be 12. We permitted a type-I error of α = 0.05 and a type-II error of β = 0.2. This analysis gave a power of 0.8 and indicated that at least 22 patients should be included in each study group (Instant; StatMate, CA). To be conservative, we decided to enrol 35 patients in each group.

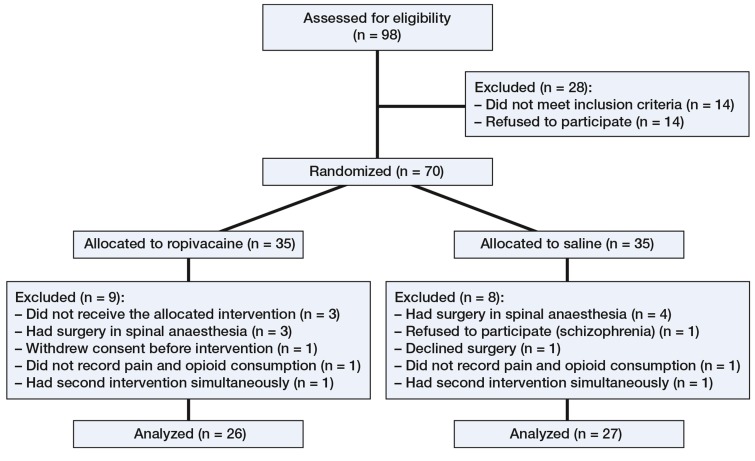

70 patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia who were undergoing the Bernese PAO between January 2009 and December 2010 were prospectively enrolled (Figure 1, Table 1). Demographic data were similar between the groups with respect to sex, age, weight, height, and duration of surgery (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Periacetabular osteotomy due to dysplasia or retroverted acetabulum | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Younger than 18 years. | |

| Comorbidities supposed to affect interpretation of pain, e.g. chronic back pain. | |

| Drug or medical abuse. Substantial opioid intake preoperatively. | |

| Mental retardation or active psychiatric disorder, e.g. depression. | |

| Spinal anesthesia. | |

| Second intervention carried out simultaneously, e.g. femur osteotomy. |

Table 2.

Characteristics of 53 patients randomized to receive postoperative wound infiltration of either ropivacaine or placebo (saline). Values are median (range) or number

| Intervention group (ropivacaine) (n = 26) |

Placebo group (saline) (n = 27) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 9/17 | 3/24 |

| Age (y) | 35 (18–54) | 31 (18–55) |

| Weight (kg) | 79 (50–127) | 70 (48–105) |

| Height (cm) | 173 (162–193) | 171 (154–193) |

| Surgeon 1/Surgeon 2 | 9/17 | 13/14 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 83 (65–110) | 77 (63–123) |

Data from 26 patients in the intervention group and 27 patients in the placebo group were analyzed. Our standardized regime was general anesthesia using propofol initiated at 2 mg/kg followed by continuous administration of 5 mg/kg/h for maintenance of anesthesia, and remifentanil initiated at 1 µg/kg followed by continuous administration of 0.5 µg/kg/min. Both were adjusted to clinical response. Long-acting opioids administered at the end of surgery and in the post-anesthesia care unit were registered as rescue analgesia.

Surgery was performed by 2 surgeons using the same modified Smith-Petersen approach and surgical technique (Hussell et al. 1999). No wound drains were used. During surgery, the patients were assigned to 1 of 2 options: (1) (The intervention group, 26 patients) Just before wound closure, patients received infiltration with 75 mL (150 mg) ropivacaine according to a systematic technique to ensure uniform distribution of the solution to all tissues incised or instrumented during the procedure. Furthermore, a multihole ON-Q Soaker Catheter (2.5-inch infusion length; I-Flow Corporation, Irvine, CA 92618, USA) connected to a bacterial filter was placed in the anterior part of the biplanar iliac osteotomy for subsequent postoperative injections. 5 postoperative bolus injections of 20 mL (50 mg) ropivacaine were given at 10-h intervals, until removal of the catheter after 2 days. (2) (The placebo group, 27 patients). Isotonic saline was injected in volumes and intervals identical to those for the intervention group.

All injections were given under double-blind conditions. To maintain blinding, the substance for injection was prepared in unmarked infusion bags by an external department, following a computer-generated random code. Besides undergoing project injections, patients in both groups were treated with the same standard medical regimen: dicloxacillin intravenously before surgery (2 g) and repeated after 8, 16, and 24 h postoperatively. Intraoperative tranexamic acid (1 g) was administered to reduce bleeding during surgery. Low-molecular-weight heparin (Dalteparin, 5,000 IE) was administered subcutaneously for 7 days after surgery for thromboprophylaxis. Furthermore, patients were prescribed metoclopramide (10 mg) for nausea, and laxative treatment was 10 mg bisacodyl.

Outcome measures

Patient-controlled analgesia was our primary outcome measure, and we registered the amount of opioid drugs consumed 5 days after wound closure.

In addition to oral paracetamol (1 g) 4 times a day, initiated in the recovery room, all the patients received PCA consisting of oral immediate-release oxycodone (5 mg) without any restrictions on the frequency of use or on the total daily dose. Patients were provided with 6-tablet blister packages, which were replaced when empty. In the recovery ward, the analgesia provided was a morphine bolus intravenously until the patients were able to consume self- administered tablets. Consumption of analgesia during the 4-day postoperative period was self-registered on specific time-sheets, which were cross-checked with the medical records, and the patient’s overall analgesic consumption was calculated and converted to mg equivalents of oxycodone using a conversion table (Hallenbeck 2003).

Pain and nausea during the 4-day postoperative period was assessed on a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 mm (no pain/nausea) to 100 mm (worst possible pain/nausea). The first assessment of pain was done by trained nurses 6 hours postoperatively. Subsequently, VAS for pain at rest and VAS for nausea were registered by the patients themselves 4 times a day in specific schedules. Pain during activity was assessed by the attending physiotherapists immediately after the timed up-and-go (TUG) test, which was performed once a day to measure mobility during the 4-day postoperative study period.

Statistics

Data entry and statistical analyses were performed with EpiData software (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) and Stata software. Data were analyzed for normal distribution. Mann-Whitney U-test (with data presented as median with interquartile range) and Student’s t-test (with data presented as mean and SD) were used where appropriate. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Bonferroni-Holm method was used to correct for multiple testing of the secondary endpoints presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Postoperative pain and timed up-and-go (TUG) results. Values are mean (SD) or number of registrations in the 2 groups. Self-reporting of pain at rest was scheduled 4 times every day. Pain during activity was assessed once a day, immediately after the TUG test

| Intervention (ropivacaine) |

Group Placebo (saline) |

Intervention/placebo, n a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS 6 h postoperatively | 29 (18) | 38 (17) | 18/19 | 0.1 |

| VAS on POD 1 | 31 (23) | 35 (21) | 97/95 | 0.2 |

| VAS on POD 2 | 24 (20) | 31 (20) | 100/100 | 0.009 b |

| VAS on POD 3 | 19 (16) | 31 (22) | 91/92 | < 0.001 b |

| VAS on POD 4 | 18 (17) | 28 (23) | 81/85 | < 0.001 b |

| TUG, POD 1 | 44 (11) | 63 (40) | 11/9 | 0.2 |

| TUG, POD 2 | 41 (18) | 39 (17) | 17/13 | 0.8 |

| TUG, POD 3 | 38 (17) | 42 (32) | 20/16 | 0.7 |

| TUG, POD 4 | 33 (16) | 42 (21) | 13/11 | 0.2 |

| VAS after TUG, POD 1 | 43 (14) | 47 (25) | 11/10 | 0.8 |

| VAS after TUG, POD 2 | 30 (14) | 38 (22) | 17/14 | 0.2 |

| VAS after TUG, POD 3 | 29 (19) | 31 (20) | 19/16 | 0.8 |

| VAS after TUG, POD 4 | 32 (22) | 33 (28) | 13/11 | 0.9 |

VAS: visual analog scale; POD: postoperative day; TUG: timed up-and-go test.

a Number of registrations in the two groups. Self reported pain was scheduled four times each day.

b Using the Bonferroni-Holm correction, the level of significance should be 0.004 (0.05/13)

Results

There were no statistically significant differences in the patients’ rating of pain 6 h postoperatively or on postoperative day 1, although pain was generally reported to be less in the intervention group. Yet, patients in the intervention group reported significantly lower pain at rest than those in the placebo group on postoperative days 3–4 (Table 3). Evaluation of TUG and the ratings of pain after TUG on postoperative days 1–4 revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups.

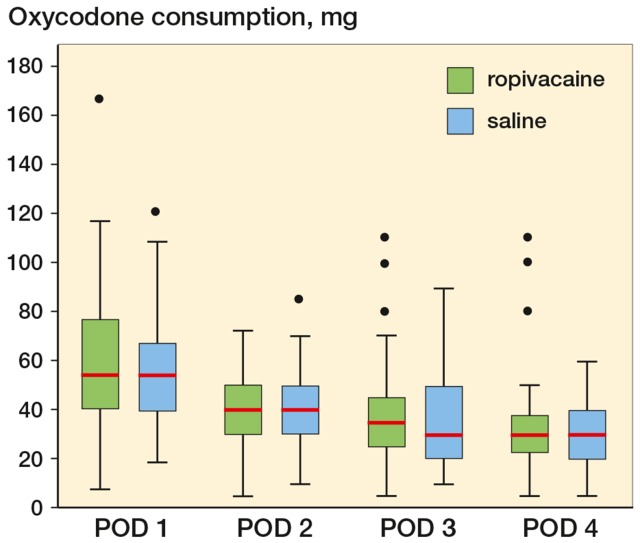

The consumption of oxycodone was similar in the 2 groups during the intervention period from postoperative day 1 to postoperative day 2 and during the rest of the observational period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Boxplot showing median oxycodone consumption postoperative day (POD) 1–4. POD 1: p = 0.66, POD 2: p = 0.86, POD 3: p = 0.57, and POD 4: p = 0.85. Boxes indicate median with 25th and 75th percentilrs and whisker caps indicate 10th and 90th percentiles. Dots show each observation outside whiskers.

Complications

No serious adverse events were observed, and the patients’ needs for anti-emetics were similar during the intervention period.

Discussion

The present study was motivated by results from other studies of the technique showing reduced opioid consumption and improved postoperative analgesia after total hip arthroplasty (THA) (Bianconi et al. 2003, Peters et al. 2006, Andersen et al. 2007b, Kerr and Kohan 2008) and total knee arthroplasty (Busch et al. 2006, Andersen et al. 2008). In contrast to these studies, however, the effect on postoperative pain was less pronounced, and we did not find any reduction in opioid consumption.

Andersen et al. (2007b) observed reduced pain and a lower requirement for rescue medication from 8 h to 96 h postoperatively with an intraoperative periarticular injection followed by top-up via intra-articular catheter on day 1. Andersen et al. (2007a) reported reduced postoperative consumption of opioids with intraoperative infiltration and top-up via catheter after 8 h, and Kerr and Cohan (2008)—although without a group of controls—found satisfactory pain scores and no requirement for postoperative morphine in two-thirds of the patients after perioperative infiltration and top-up via catheter postoperatively.

In addition to the different nature of the surgery performed in our study, possible explanations for the less pronounced effect of wound infiltration may relate to differences in the solution injected. We chose the long-acting local anesthetic ropivacaine, which had been used successfully in previous trials (Andersen et al. 2007a,b, Kerr and Kohan 2008) and is believed to be less toxic than bupivacaine (Knudsen et al. 1997). We used ropivacaine alone for injections, in contrast to other investigators (Busch et al. 2006, Andersen et al. 2007a,b, 2008, Kerr and Kohan 2008) who included ropivacaine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gabapentinoids, and selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors to target the various pathways involved in nociception, all as elements of multimodal perioperative pain tratment.

We deliberately excluded the extensive multimodal analgesic approach because we wanted to determine whether infiltration with pure ropivacaine could reduce consumption of opioid and also induce significant postoperative pain relief. The rationale was on the one hand to estimate the effective contribution of ropivacaine as part of a potential more comprehensive regimen in future, and on the other to reduce the risk of possible side effects such as impaired bone healing from NSAIDs and COX2s (Harder and An 2003) and cardiovascular risk (Souter et al. 1994). Epinephrine was not added because ropivacaine in itself has vasoconstrictive properties (Dahl et al. 1990).

Several other factors may have contributed to the difference from previous studies. We used a minimally invasive approach for PAO, and the area available for infiltration is smaller than in hip arthroplasty. Based on a pilot period, we considered the 75-mL volume to be adequate for extensive and standardized infiltration into the periost and the soft tissues surrounding the osteotomy. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that our limited volume—compared to the 150–200 mL recommended by Kerr and Kohan (2008) or the 100 mL volume reported by Busch et al. (2010)—is suboptimal, even though the exact influence of volume on intervention and placebo is not clear (Andersen et al. 2010a).

To consider our intervention to be analgesic required that we had to take 2 interdependent outcomes into account: pain and analgesic consumption. Dealing with pain as the only outcome presupposes that analgesic intake is fixed at a strictly defined uniform level, which must, however, be low enough to allow some degree of pain. The rationale of our study design was that we assumed that patients were quite capable of administering PCA, and would therefore end up with the same VAS score in both groups. Consequently, a measure of consumption of opiod as rescue analgesia was chosen as primary outcome. A setup with pain rating of fixed analgesic regimes without any rescue medication for the treatment of possible pain breakthrough would be ethically unacceptable. Conversely, the concept of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) has proven to be effective for acute pain management (Lehmann 2005), so we used patient-controlled opioid consumption as primary outcome, assuming that PCA without restrictions on the frequency or the total daily dose would offer the best possible pain relief for the subjects and that consumption of rescue analgesia would be a reliable outcome for evaluation of our intervention in addition to measuring pain.

The participating subjects were in good mental health, and the quantities of rescue analgesics consumed—compared to what we consider to be acceptable pain ratings—indicate that the subjects were able to manage self-administration of analgesics in a sufficient way. Even so, consumption of analgesics was equal in the groups whereas we found statistically significant reduction in pain in the intervention group on days 3 and 4. Our concept with orally administered PCA may provide a less sophisticated estimation of opioid consumption than intravenous PCA from electronically controlled infusion pumps, which allow evaluation of small differences. However, we believe that a setup consisting of a pump, control button, and cables might obstruct early mobilization and carry a risk of dropouts because of complications associated with the peripheral venous catheters—and that these disadvantages are offset by the possibility of precluding a small, albeit not clinically relevant, difference in rescue medication between the groups.

The difference in VAS score from 6–10 mm was probably not clinically significant (Gallagher et al. 2001). This possible lag in clinical significance can explain our observations of equal analgesic consumption in spite of statistically significant differences in VAS.

We acknowledge that the present study had several limitations. VAS assessed 6 h postoperatively could be biased by hyperalgesia in the immediate postoperative period (Angst et al. 2003), and the variable recovery of patients from anesthesia, since prolonged recovery after recovery after general anesthesia necessitates that assessment of pain and administration of analgesics be carried out by caregivers in the recovery ward based on their subjective estimate of patients’ needs. However, we expect these possible confounders from anesthesia to be equalized from day 2. General anesthesia was chosen as the method of anesthesia since this procedure is standard in our department for PAO. Furthermore, we predicted differences in recovery times after spinal anesthesia. The uneven sex distribution in the groups was by chance. We cannot exclude an effect from this, although sex differences regarding pain are a controversial issue (Racine et al. 2012).

Opioid consumption and pain were similar 6 h postoperatively and on postoperative days 1–2. Thus, we have found no indication that intraoperative infiltration with 75 mL (150 mg) ropivacaine followed by 20-mL bolus injections (150 mg) of ropivacaine postoperatively in addition to paracetamol does reduce pain or opioid requirements during the immediate postoperative period.

On postoperative days 3–4, however, pain ratings from patients receiving local infiltration with ropivacaine were lower than those in the placebo group. We cannot give an exact explanation for this, since it seems unlikely that there would be an improved specific effect from the much smaller volumes of ropivacaine injected through the catheters 3–4 days postoperatively. The benefits of postoperative injections through catheters are controversial, since they have been observed to reduce pain in some studies (Essving et al. 2010) while others have found no effect of this modality (Andersen et al. 2010b, Specht et al. 2011). Placement of catheters varies with different surgical procedures, which may influence the effects, while wound spread of the injected solution appears to be less affected by the type of catheter used (Andersen et al. 2010c). Also, the time intervals between the catheter injections may have some relevance. We chose 10-h intervals, while others have reported intervals of up to 24 h between intraoperative and postoperative catheter injections (Andersen et al. 2007b). The half-life of ropivacaine may vary according to the surrounding tissues and changes in local blood flow (Pettersson et al. 1998). In PAO, substantial absorption-dependent elimination from the exposed cancellous bone in the osteotomized bones cannot be excluded. Furthermore, this may allow a slight systemic analgesic effect from the ropivacaine injected both peroperatively and postoperatively through the catheter placed in the greater osteotomy of the ilium.

The strengths of our study include the randomized design and standardization of the delivery of intervention, which would limit bias due to possible differences in outcome caused by factors other than the intervention. The blinding of patients, surgeons, caregivers, and assessors further minimizes bias, this time from expectations.

In summary, the clinical importance of ropivacaine as single component in postoperative treatment of pain is questionable, and we are planning further studies to explore the potential of LIA in multimodal approaches for treatment of pain in this category of patients.

Acknowledgments

RDB: enrollment of patients, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. OO and SO: enrollment of patients, surgery, and contribution to the manuscript. PL: anesthetic responsibility and contribution to the manuscript.

The study was supported by grants from Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; from Region of Southern Denmark Research; and from the Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Foundation. No sponsors took part in organizing the study, in analysis, or in writing of the manuscript. We thank the nurses at the orthopedic surgery department and PACU of Odense University Hospital; in particular, we thank research nurse Annie Gam-Pedersen for her efforts in registration of the subjects participating in the project.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Andersen KV, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Haraldsted V, Soballe K. Reduced hospital stay and narcotic consumption, and improved mobilization with local and intraarticular infiltration after hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial of an intraarticular technique versus epidural infusion in 80 patients . Acta Orthop. 2007a;78(2):180–6. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LJ, Poulsen T, Krogh B, Nielsen T. Postoperative analgesia in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled study on peroperative and postoperative ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline wound infiltration . Acta Orthop. 2007b;78(2):187–92. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LO, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(10):1331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LO, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of local anaesthetic wound administration in knee arthroplasty: volume vs concentration . Anaesthesia. 2010a;65(10):984–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LO, Husted H, Kristensen BB, Otte KS, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of subcutaneous local anaesthetic wound infiltration in bilateral knee arthroplasty: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010b;54(5):543–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LO, Kristensen BB, Madsen JL, Otte KS, Husted H, Kehlet H. Wound spread of radiolabeled saline with multi- versus few-hole catheters . Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010c;35(2):200–2. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181c7733d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst MS, Koppert W, Pahl I, Clark DJ, Schmelz M. Short-term infusion of the mu-opioid agonist remifentanil in humans causes hyperalgesia during withdrawal . Pain. 2003;106(1-2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianconi M, Ferraro L, Traina GC, Zanoli G, Antonelli T, Guberti A, Ricci R, Massari L. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of ropivacaine continuous wound instillation after joint replacement surgery . Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(6):830–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch CA, Shore BJ, Bhandari R, Ganapathy S, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, McCalden RW. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(5):959–63. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch CA, Whitehouse MR, Shore BJ, MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW, Bourne RB. The Efficacy of Periarticular Multimodal Drug Infiltration in Total Hip Arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(8):2152–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi PT, Bhandari M, Scott J, Douketis J. Epidural analgesia for pain relief following hip or knee replacement . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD003071. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl JB, Simonsen L, Mogensen T, Henriksen JH, Kehlet H. The effect of 0.5% ropivacaine on epidural blood flow . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(4):308–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1990.tb03092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced morphine consumption and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia (LIA) following total knee arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):354–60. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.487241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale . Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(6):633–8. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.118863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck J. Palliative care perspectives. In: Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003.

- Harder AT, An YH. The mechanisms of the inhibitory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on bone healing: a concise review . J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43(8):807–15. doi: 10.1177/0091270003256061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussell JG, Mast JW, Mayo KA, Howie DW, Ganz R. A comparison of different surgical approaches for the periacetabular osteotomy . Clin Orthop. 1999;363:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DR, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):174–83. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen K, Beckman SM, Blomberg S, Sjovall J, Edvardsson N. Central nervous and cardiovascular effects of i.v. infusions of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and placebo in volunteers . Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):507–14. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann KA. Recent developments in patient-controlled analgesia . J Pain Symptom Manage (5 Suppl) 2005;29:S72–S89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CL, Shirley B, Erickson J. The effect of a new multimodal perioperative anesthetic regimen on postoperative pain, side effects, rehabilitation, and length of hospital stay after total joint arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty (6 Suppl 2) 2006;21:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson N, Emanuelsson BM, Reventlid H, Hahn RG. High-dose ropivacaine wound infiltration for pain relief after inguinal hernia repair: a clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation . Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23(2):189–96. doi: 10.1097/00115550-199823020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine M, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Kloda LA, Dion D, Dupuis G, Choiniere M. A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and experimental pain perception - part 1: are there really differences between women and men? . Pain. 2012;153(3):602–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souter AJ, Fredman B, White PF. Controversies in the perioperative use of nonsterodial antiinflammatory drugs . Anesth Analg. 1994;79(6):1178–90. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199412000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht K, Leonhardt JS, Revald P, Mandoe H, Andresen EB, Brodersen J, Kreiner S, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P. No evidence of a clinically important effect of adding local infusion analgesia administrated through a catheter in pain treatment after total hip arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):315–20. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.570671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]