Abstract

Background and purpose

High primary stability is important for long-term survival of uncemented femoral stems. Different stem designs are currently in use. The ABG-I is a well-documented anatomical stem with a press-fit design. The Unique stem is designed for a tight customized fit to the cortical bone of the upper femur. This implant was initially developed for patients with abnormal anatomy, but the concept can also be used in patients with normal femoral anatomy. We present 5-year radiostereometric analysis (RSA) results from a randomized study comparing the ABG-I anatomical stem with the Unique femoral stem.

Patients and methods

100 hips with regular upper femur anatomy were randomized to either the ABG-I stem or the Unique femoral stem. RSA measurements were performed postoperatively and after 3, 6, 12, 24, and 60 months.

Results

RSA measurements from 80 hips were available for analysis at the 5-year follow-up. Small amounts of movement were observed for both stems, with no statistically significant differences between the 2 types.

Interpretation

No improvement in long-term stability was found from using a customized stem design. However, no patients with abnormal geometry of the upper femur were included in this study.

High mechanical stability is a crucial factor for correct performance of uncemented femoral stems. Micromovements along the implant-bone interface may prevent ingrowth of bone to the surface of the prosthesis, and it may lead to the formation of a fibrous membrane and eventually to loosening of the implant. The critical thresholds of micromovements that can be tolerated are not exactly known, but they are probably dependent on both patient- and implant-specific factors (Viceconti et al. 2006). It has been shown, however, that interfacial motion of around 40 μm leads to partial bone ingrowth whereas motions exceeding 150 μm completely prevent ingrowth of bone (Pilliar et al. 1986, Jasty et al. 1997).

Uncemented, customized femoral stems are mainly designed and manufactured for patients with abnormal size and shape of the proximal femur, but this does not preclude their use in patients with regular-shaped proximal femurs. The requirement for maximum primary stability with uncemented off-the-shelf stems also applies to customized stems. The optimized fit and fill of a customized stem should theoretically promote even better mechanical fixation than with standard implants.

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) enables measurement of migration and rotation in the range of 0.1 mm and 0.05º, respectively (Selvik 1989, Kadar et al. 2011). There is a correlation between postoperative migration of femoral stems and early loosening (Freeman and Plante-Bordeneuve 1994, Linder 1994, Karrholm et al. 2006, Karrholm 2012). On the other hand, a new implant showing large degrees of micromovement should not necessarily be regarded as having a performance equivalent to long-term failure (Karrholm et al. 2006). Recently published studies reporting medium- to long-term RSA results will probably contribute to a better understanding of the topic (Nieuwenhuijse et al. 2012, Rohrl et al. 2012).

This randomized study was performed as part of the clinical documentation of the Unique customized stem (Scandinavian Customized Prosthesis (SCP), Trondheim, Norway), to compare the migration pattern of the Unique stem with that of a standard anatomical uncemented stem with a clinically well-proven stem design (the ABG-I).

Our aim was to measure migration of the Unique customized stem and the ABG-I stem using RSA. Our hypothesis was that there would be no difference in migration between the 2 types of uncemented femoral stems in patients with regular anatomy in the upper femur.

Patients and methods

From January 1999 through April 2001, patients less than 65 years of age with primary or secondary osteoarthritis were prospectively included in the study. Those with dysmorphic anatomy in the upper femur who were therefore less well suited for a standard femoral arthroplasty were excluded. We defined dysmorphic anatomy as extremely narrow or wide intramedullary cavity, angular deformity in the upper femur, or highly abnormal anteversion of the femoral neck. Patients were recruited in the outpatient clinic at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Trondheim University Hospital. A trial coordinator performed a block randomization with sealed, opaque envelopes. The envelopes were opened in the outpatient clinic after the patients had signed the informed consent document. 100 hips were randomized to receive either the Unique uncemented, customized femoral stem or the anatomical ABG-I stem (Stryker-Howmedica, Allendale, NJ).

4 experienced surgeons performed all the operations, with the patient in lateral decubitus position and a direct lateral approach. All the patients received antibiotic prophylaxis for the first 24 h and low-molecular-weight heparin for the first 14 days. The postoperative rehabilitation protocol was the same in both groups. All patients were allowed full weight bearing immediately after surgery, but they were advised to use 2 crutches for 8 weeks.

The patients were clinically evaluated according to the Merle d’Aubigné (MdA) score measuring joint mobility, pain, and ability to walk. Additionally, all patients reported pain on a visual analog scale, rating it from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain). Satisfaction was rated on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning a high degree of satisfaction. These evaluations took place after 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 60 months.

Both types of stems were made of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4Va) with a modular head and no collar (Figure 1). They are both undersized distally to avoid endocortical contact. The custom design of the Unique stem is based on CT-scans of the proximal femur. Using a semiautomatic computer algorithm, closed contours are generated along pixels on the scans representing a CT density of 600 Hounsfield units (HUs). Then, a computer model of the stem is generated before manufacture, using a computer-aided milling technique. The stem is downscaled by 0.75 mm in diameter to take account of the partial volume effect on the CT-scans (Aamodt et al. 1999, 2001). It is covered by a circumferential plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite (HA) coating on its proximal two-thirds. The layer is 50 µm thick with a crystallinity of 62%; distally, the stem is unpolished and has a roughness of 2.5 µm. Hip joint mechanics are optimized by offering individualized neck offset, anteversion, and length.

Figure 1.

The implants: the ABG-I stem on the left and the Unique stem on the right.

The ABG-I stem has an anatomical press-fit design with plasma-sprayed HA layer with a macro-relief surface on the proximal third. The HA layer has a thickness of 60 µm and a crystallographic composition of 98–99% at the metaphyseal level. The cervical-diaphyseal angle is 135°.

The uncemented Duraloc component was used on the acetabular side (DePuy, Leeds, UK), except in 1 patient who received the cemented Elite Plus Ogee cup (also DePuy).

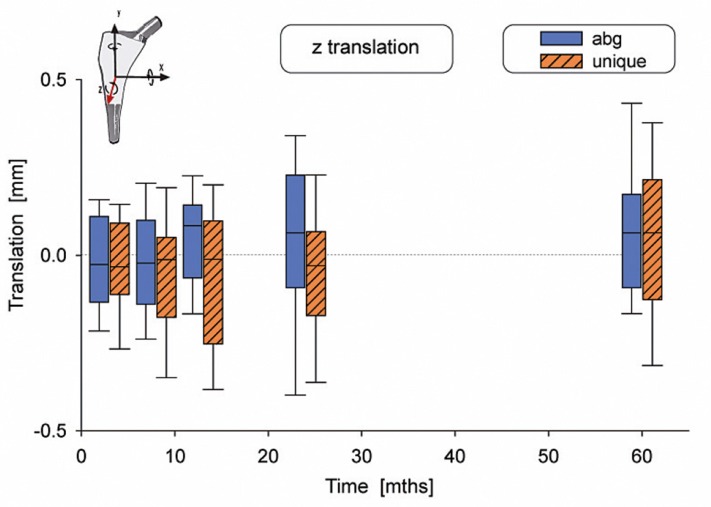

100 hips were randomized (Figure 2). 4 patients (4 hips) in the ABG-I group were excluded, 2 due to delay of the operation and 2 because they missed the postoperative RSA examinations. 6 patients, 3 in each group, were enrolled for staged bilateral arthroplasty; however, we later excluded the last-operated hip in each of these patients to maintain independence of data. 90 patients (57 women) were finally included (90 hips) (Table 1). 10 of these patients were lost to 5-year follow-up, resulting in 39 patients in the ABG-I group and 41 patients in the Unique group. Those who were excluded due to high condition number were still part of the clinical evaluation.

Figure 2.

Consort flow chart.

Table 1.

Study samples

| ABG-I | Unique | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 43 | 47 |

| Age | 53 | 55 |

| Male/female | 14/29 | 19/28 |

| Primary osteoarthritis | 21 | 31 |

| Hip dyplasia | 19 | 9 |

| Sequelae Perthes’ disease | 1 | 3 |

| Posttraumatic | 1 | 3 |

| Avascular head necrosis | 1 | 1 |

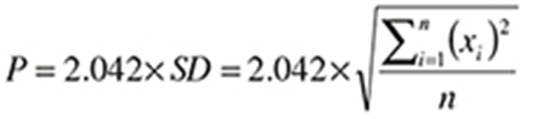

A marker-based RSA system was used (UmRSA version 5.0; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) to measure the rotations and translations of the stems. Tantalum markers were embedded into the upper femur during the operation, 5 in the greater trochanter and 4 in the lesser trochanter region. The manufacturers attached the tantalum markers to both types of stems. The ABG-I had 3 markers: 1 at the medial side, 1 at the tip, and 1 at the shoulder of the prosthesis. In the Unique stems 1 marker was attached to the medial side of the neck, 1 at the shoulder, and 1 at the tip of the prosthesis. The reference RSA examinations were carried out within 7 days postoperatively, after weight bearing, then follow-ups were carried out after 3, 6, 12, 24, and 60 months. The micromovements of the stem were measured as rotations around and translations along 3 orthogonal axes. The precision values were calculated according to current recommendations (Ranstam et al. 2000). Double examinations were carried out on 30 hips at the 5-year follow-up. The patients were repositioned between the examinations. Secondly, the standard deviation (SD) of the differences with respect to zero was calculated. The precision was then calculated using the formula:

|

where P = precision, x = the difference between double examinations, n = 30, and 2,042 represents the critical value in a 2-sided 95% t-distribution for a sample size of 30.

Examinations with a condition number (CN) of < 150 and a mean error of < 0.35 mm were included. 8 RSA scenes were excluded due to high condition number (Figure 2).

Statistics

The 6 motion outcome variables (dependent variables) were continuous. The dataset had 5% missing data with no consecutive replacement of missing values (Heck et al. 2010). Q-Q plots were used to test whether data were normally distributed. The motion data were not found to be normally distributed and they were therefore presented as box plots. The 95% confidence intervals of the medians were calculated by bootstrapping, BCa 1,000 iterations. Linear mixed models (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20) were used to compare migrations between the 2 groups of prostheses. Baseline characteristics were not included in the models. Each of the 6 movements was analyzed separately holding the type of prosthesis as a factor and time as covariant. Initially the 5 other movements were included as covariates. Statistically non-significant covariates were removed to identify the most parsimony models (Cheng et al. 2010). Toeplitz covariance structure was chosen in level 1 (patients’ measured repeatable by time) to account for data covariance within each patient. Akaike’s information criterion was used in model comparisons. The level-1 residuals were found to be normally distributed in all 6 models. The level of statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were done using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (No. 70-98) and it was carried out according to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (version 4).

Results

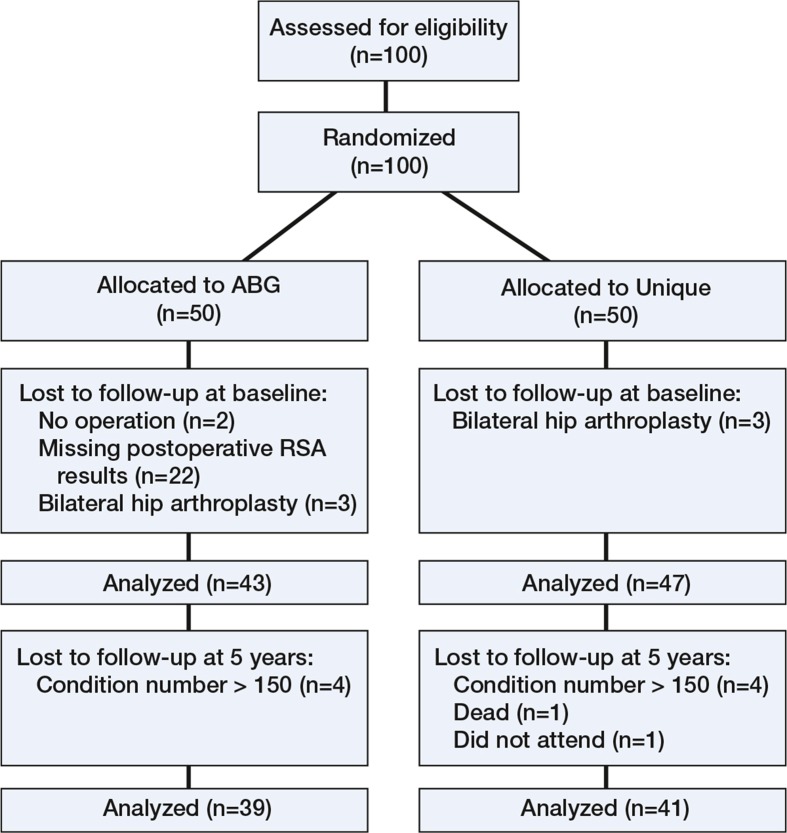

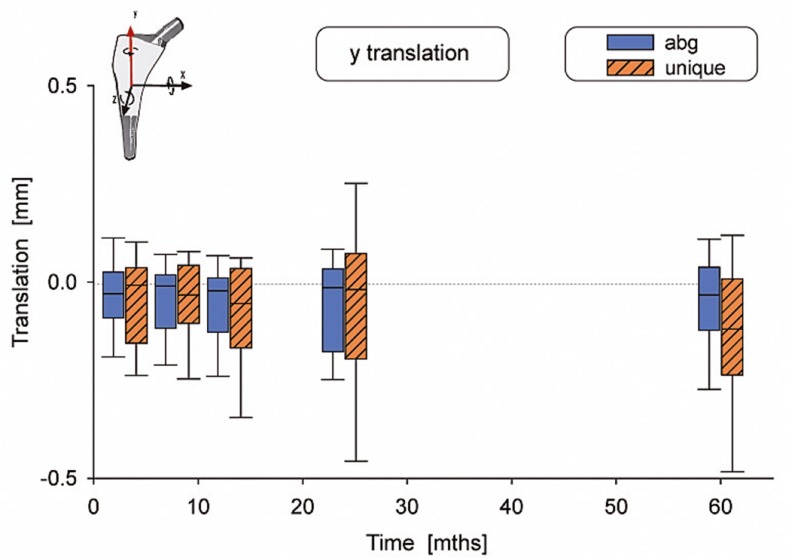

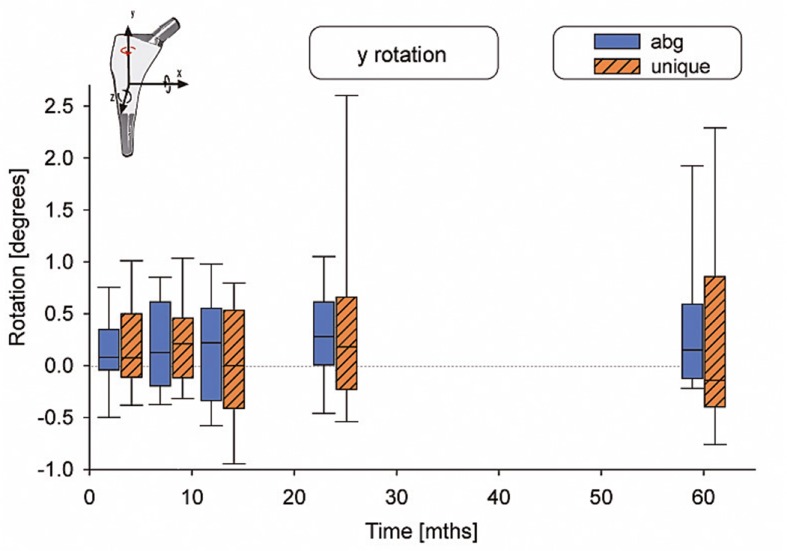

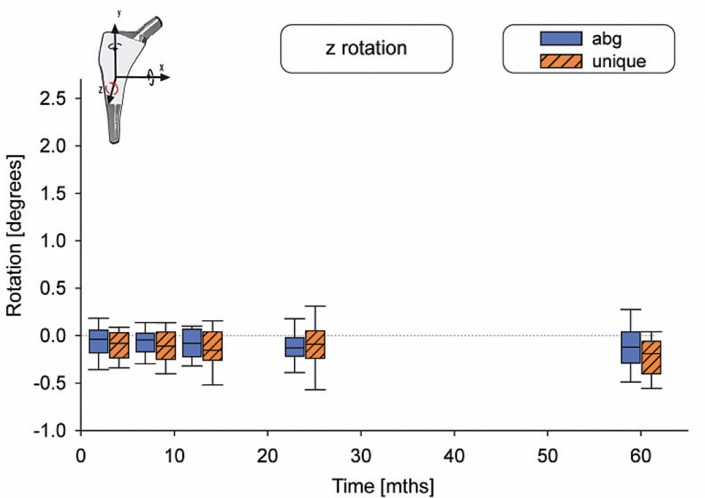

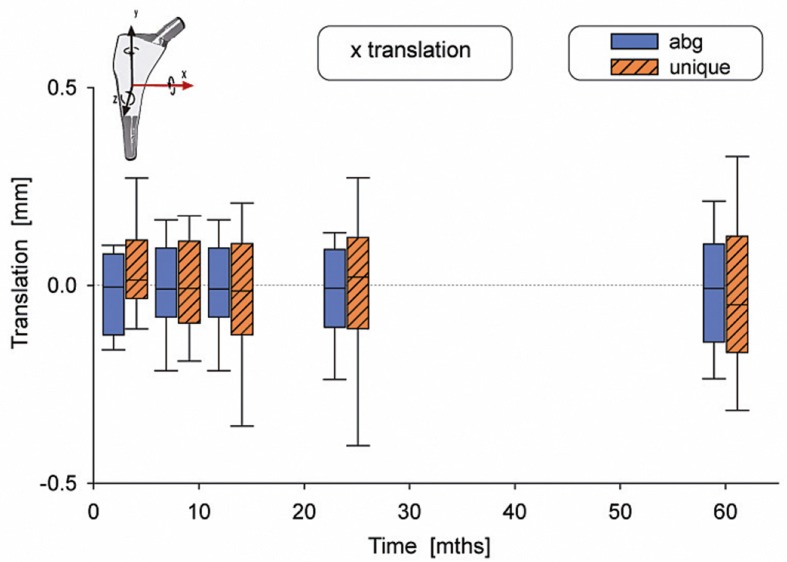

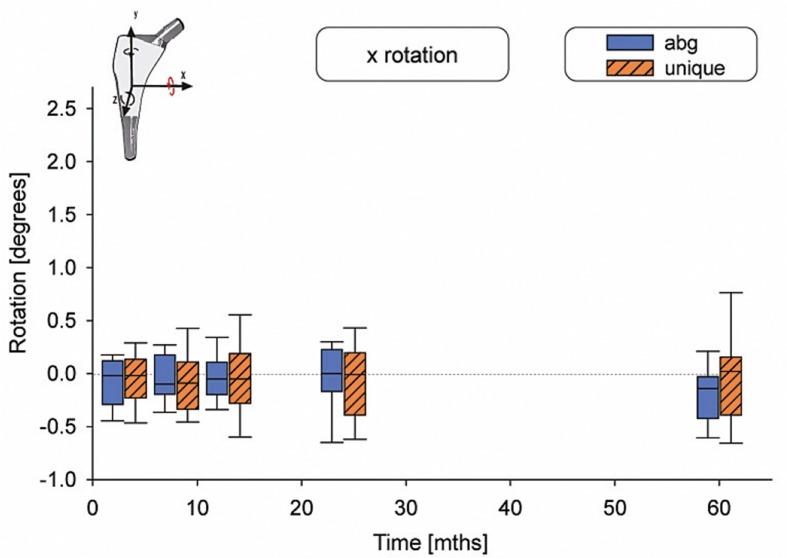

There were no statistically significant differences in motion between the 2 types of stems (Table 2). The median subsidence (translation along the y-axis) was –0.03 mm for the ABG-I stem and –0.13 mm for the Unique stem (Figure 3). The median retroversion (rotation around the y-axis) was 0.15º for the ABG-I stem and –0.08º for the Unique stem (Figure 4). 1 stem in the Unique group subsided 5.3 mm within the first year, and then it stabilized. Further examinations showed no signs of loosening, either radiographically or clinically. Figures 3–8 show all 6 movements for the total time period up to 5 years. Time as a factor was statistically significantly related to the following 4 movements: translation along the y- and z-axis and rotation around the x- and z-axis.

Table 2.

Migration data and RSA precision data measurement at five-year follow-up. The p-values refer to statistical testing of differences in motion between the 2 types of stem and the effect of time versus motion

| Implant | Median 5-year | Range | 95%CI of the median | p-value, difference in motion | Difference in motion 95%CI | p-value, time vs. motion | RSA precision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x-rot [deg] | ABG-I | –0.14 | –1.10 to 1.02 | –0.26 to –0.07 | 0.64 | –0.14 to 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.52 |

| Unique | 0.02 | –1.67 to 1.45 | –0.09 to 0.06 | |||||

| y-rot [deg] | ABG-I | 0.15 | –0.89 to 2.93 | –0.01 to 0.36 | 0.41 | –0.14 to 0.33 | 0.08 | 1.36 |

| Unique | –0.08 | –1.66 to 4.43 | –0.30 to 0.56 | |||||

| z-rot [deg] | ABG-I | –0.12 | –0.87 to 0.58 | –0.17 to –0.08 | 0.31 | –0.04 to 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Unique | –0.20 | –0.94 to 0.49 | –0.35 to –0.14 | |||||

| x-trans [mm] | ABG-I | –0.03 | –0.41 to 0.33 | –0.10 to 0.03 | 0.20 | –0.08 to 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.19 |

| Unique | –0.05 | –1.02 to 0.78 | –0.13 to 0.04 | |||||

| y-trans [mm] | ABG-I | –0.03 | –0.50 to 0.27 | –0.09 to –0.01 | 0.15 | –0.07 to 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Unique | –0.13 | –5.36 to 0.59 | –0.18 to –0.05 | |||||

| z-trans [mm] | ABG-I | 0.06 | –0.36 to –0.78 | 0.01 to 0.11 | 0.32 | –0.05 to 0.14 | <0.01 | 0.37 |

| Unique | 0.07 | –0.80 to 1.94 | 0.01 to 0.16 |

Figure 3.

Translation along the y-axis. The whiskers show the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Figure 4.

Rotation around the y-axis.

Figure 5.

Translation along the z-axis.

Figure 6.

Rotation around the z-axis.

Figure 7.

Translation along the x-axis.

Figure 8.

Rotation around the x-axis

The mean preoperative Merle d’Aubigné score was 11 (7–14) in the ABG-I group and 10 (6–13) in the Unique group. After 5 years, the mean score was 17 (13–17) in both groups. Preoperatively, the mean score for pain was 6.5 in both groups. After 5 years, the mean pain reported was 1.1 in the ABG-I group and 1.0 in the Unique group. Regarding the mean value on the satisfaction scale, after 5 years it was 1.1 in the ABG-I group and 0.7 in the Unique group.

None of the hips were revised during the study period, but 5 patients had complications. In the ABG-I group, 2 patients had a deep venous thrombosis and 2 patients had an early dislocation. In the Unique group, 1 patient had a common peroneal nerve dysfunction.

Discussion

Because some uncemented femoral stem designs had inferior survival 15–20 years ago, a group of orthopedic surgeons and engineers at our hospital adopted the concept of customization of the implant. The theory was that an individually designed femoral stem would achieve increased mechanical stability and more physiological bone remodeling around the stem, and thus a longer clinical survival. This stem is commercially available, but is more than twice as expensive as a regular stem. The present study is part of the stepwise and comprehensive documentation of this particular prosthesis, involving both experimental and clinical studies (Aamodt et al. 1999, 2001, Benum and Aamodt 2010)

We found a small and similar degree of micromotion in the ABG-I stem and the Unique stem. Time was a statistically significant factor for 4 of the 6 movements, but the motions were small. Thus, both groups of stems must be regarded as stable. The more extreme fit and fill concept of the Unique stem did not improve the stability of the stem compared to that of a standard anatomical stem when implanted into regular-shaped femurs. Possible effects of the individual-based neck geometry were not investigated in the present study.

Several factors are required to achieve stable uncemented femoral stems and to facilitate bone ingrowth. In vitro studies of micromotion have revealed that proximal fit is important for rotational stability (Pilliar et al. 1986, Burke et al. 1991, Callaghan et al. 1992, Ostbyhaug et al. 2010). It is recommended that titanium femoral stems with proximal HA coating should have good metaphyseal fit and fill to achieve initial biological fixation (Jaffe and Scott 1996).

The anatomical ABG-I stem is based on the principle of proximal fit and fill. Several authors have reported good results for the stem (Tonino et al. 1995, Giannikas et al. 2002, Rogers et al. 2003, Bidar et al. 2009). Regarding stability, when evaluating stability related to weight bearing after total hip arthroplasty, Thien et al. (2007) found that the ABG-I stem was stable both for subsidence and rotation. On the other hand, the anatomical stems require regular anatomy in the upper femur to be insertable. The best results for the ABG stem have been reported for femurs with a regular or stovepipe shape (van der Wal et al. 2008). Patients with a champagne-flute femur (Dorr type A) showed a high degree of tight distal fit and loose proximal fit; thus, the anatomical design of the ABG stems might cause problems for patients with non-conformity femurs (Dorr et al. 1990).

Early reports regarding stability and clinical performance of smooth, uncemented customized stems had varying results. 3 studies dealt with clinical results of the Identifit stem (Depuy), which was machined intraoperatively based on a mold of the femoral canal. Importantly, none of these stems had any form of surface coating or texture, which may have contributed to the high failure rate of this particular type of customized stem. At 2-year follow-up, 65% of the Identifit stems had subsided more than 2 mm and 27% had migrated into varus (Robinson and Clark 1996), and a 6-month follow-up study found that 73% of the stems had subsided by more than 2 mm (Mathur et al. 1996). A smooth optimal canal fit and fill design appears to be inadequate for gain of stability, leading to 28% failure of this customized stem design within 2 years of surgery (Lombardi et al. 1995).

Hydroxyapatite-coated customized femoral stems, produced with CAD/CAM technique and based on 3-D CT-scans of the patient’s femur, have shown better results—both clinically and radiographically (Wettstein et al. 2005, Koulouvaris et al. 2008, Benum and Aamodt 2010). In the latter study of the Unique stem, no aseptic loosening was found in 83 hips at 10-year follow-up.

We are aware of only 1 other study that has evaluated the in vivo stability of the Unique stem. In that study, the Unique stem was compared to a standard cemented stem (the Elite Plus) (Grant et al. 2005). At 2 years, the stems in both groups were stable with a mean migration of less than 0.18 mm, which is in accordance with our results. The cemented arthroplasty moved 1.05º into retroversion compared to 0.01º for the Unique stem, which was a statistically significant difference.

We realize that our study had some limitations. The Unique stem was primarily designed for patients with deviant anatomy; the results of this study may not be valid for such patients. The ABG-I and the Unique prostheses differed regarding the extent of HA coating. The ABG-I prosthesis has an HA layer on the proximal third while on the Unique stem, the HA coating covers approximately two-thirds of the device. The difference in level of coating did not affect the results regarding stability.

Despite randomization of the patients, there was a striking difference between the groups regarding diagnosis. However, we do not believe that the higher number of dysplastic hips in the ABG group would have a substantial effect on the results because the dysplastic changes were mainly located on the acetabular side, and not on the femoral side.

No statistical power analysis was done before the study. The estimation of sample size was based on the numbers of patients included in similar studies (Karrholm et al. 1994, 1997). However, using the results presented in Table 2 combined with the following additional results on standard deviations (y-rotation: ABG-I 0.90, Unique 1.30; z-rotation: ABG-I 0.31, Unique 0.29; and y-translation: ABG-I 0.16, Unique 0.89), retrospective power analyses were performed (G*Power version 3.1.5, University of Kiel, Germany) (α = 0.05, β = 0.80, 2 tails, 2 groups, Wilcoxon-Man-Whitney test). Approximately, subsidence larger than 0.51 mm, rotation greater than 0.99º (translation along and rotation around the y-axis), and varus tilt of more than 0.51º (rotation around the z-axis) would have been recognized as being statistically significant. We therefore believe that relevant clinical differences would have been detected with the number of patients attending the 60-month follow-up.

An RSA study including patients with abnormal femoral anatomy would only be feasible in a study with a prospective, single-series design. The strength of our study was that we performed a randomized controlled trial evaluating stability in 2 principally different uncemented stem designs with an accurate method. On the other hand, it is a limitation that the study was carried out on patients with normal anatomy of the upper femur while the prosthesis was mainly designed for patients with abnormal hip anatomy.

A study of bone remodeling around the same stem designs that we used revealed that there was a similar amount and pattern of proximal bone loss after 5 years (Nysted et al. 2011). Götze et al. (2009) compared a customized implant with a conventional implant, with respect to gait analysis as well as clinical and radiographic outcomes. They did not find improved results in the customized group, and therefore advised against further use of customized stems in patients with primary arthritis, due to the increased cost. We recommend custom-made femoral stems as an alternative in cases with substantial anatomical deformities of the upper femur. In normal cases, we suggest that a well-documented standard stem would be the best, most cost-effective alternative.

In a prospective clinical study with 7–10 years of follow-up, the Unique stem performed well both in patients with regular femur shape and in patients with abnormalities of the upper femur (Benum and Aamodt 2010). Clinical use of the Unique stem in patients with such deformities shows good results. Long-term observation of other outcomes, such as implant survival, are needed to decide whether use of the more expensive customized stem would offer any clinical advantages.

Acknowledgments

MN took part in analyzing the data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors took part in later revisions and approved the final manuscript. OF took part in analyzing the data. JK took part in analyzing the data and designing the figures. KH performed the RSA measurements. PB and AA were responsible for development of the custom femoral stem, the design of the study, and collection of data. They also performed most of the surgical procedures together with OSH, who also took part in collecting the data.

None of the authors has received financial support from the manufacturer of the Unique stem (Scandinavian Customized Prostheses (SCP), Trondheim, Norway). AA is an unsalaried member of the Board and is a representative of the research group that took part in the development of the implant.

References

- Aamodt A, Kvistad KA, Andersen E, Lund-Larsen J, Eine J, Benum P, et al. Determination of Hounsfield value for CT-based design of custom femoral stems . J Bone and Joint Surg (Br) 1999;81(1):143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aamodt A, Lund-Larsen J, Eine J, Andersen E, Benum P, Husby OS. Changes in proximal femoral strain after insertion of uncemented standard and customised femoral stems. An experimental study in human femora . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001;83(6):921–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b6.9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benum P, Aamodt A. Uncemented custom femoral components in hip arthroplasty. A prospective clinical study of 191 hips followed for at least 7 years . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(4):427–35. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.501748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidar R, Kouyoumdjian P, Munini E, Asencio G. Long-term results of the ABG-1 hydroxyapatite coated total hip arthroplasty: analysis of 111 cases with a minimum follow-up of 10 years . Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(8):579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke DW, O’Connor DO, Zalenski EB, Jasty M, Harris WH. Micromotion of cemented and uncemented femoral components . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991;73(1):33–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan JJ, Fulghum CS, Glisson RR, Stranne SK. The effect of femoral stem geometry on interface motion in uncemented porous-coated total hip prostheses. Comparison of straight-stem and curved-stem designs . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1992;74(6):839–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Edwards LJ, Maldonado-Molina MM, Komro KA, Muller KE. Real longitudinal data analysis for real people: building a good enough mixed model . Stat Med. 2010;29(4):504–20. doi: 10.1002/sim.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr LD, Absatz M, Gruen TA, Saberi MT, Doerzbacher JF. Anatomic Porous Replacement hip arthroplasty: first 100 consecutive cases . Semin Arthroplasty. 1990;1(1):77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MA, Plante-Bordeneuve P. Early migration and late aseptic failure of proximal femoral prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76(3):432–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannikas KA, Din R, Sadiq S, Dunningham TH. Medium-term results of the ABG total hip arthroplasty in young patients . J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(2):184–8. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.29394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotze C, Rosenbaum D, Hoedemaker J, Bottner F, Steens W. Is there a need of custom-made prostheses for total hip arthroplasty? Gait analysis, clinical and radiographic analysis of customized femoral components . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(2):267–74. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0717-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P, Aamodt A, Falch JA, Nordsletten L. Differences in stability and bone remodeling between a customized uncemented hydroxyapatite coated and a standard cemented femoral stem - A randomized study with use of radio stereometry and bone densitometry . J Orthop Res. 2005;23(6):1280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.03.016.1100230607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas SL, Rabata LN. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling with IBM SPSS. Routledge, Taylor and Francis group, New York. 2010.

- Jaffe WL, Scott DF. Total hip arthroplasty with hydroxyapatite-coated prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;78(12):1918–34. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199612000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasty M, Bragdon C, Burke D, O’Connor D, Lowenstein J, Harris WH. In vivo skeletal responses to porous-surfaced implants subjected to small induced motions . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1997;79(5):707–14. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadar T, Hallan G, Aamodt A, Indrekvam K, Badawy M, Skredderstuen A, et al. Wear and migration of highly cross-linked and conventional cemented polyethylene cups with cobalt chrome or Oxinium femoral heads: a randomized radiostereometric study of 150 patients . J Orthop Res. 2011;29(8):1222–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J. Radiostereometric analysis of early implant migration - a valuable tool to ensure proper introduction of new implants . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(6):551–2. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.745352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76(6):912–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Herberts P, Hultmark P, Malchau H, Nivbrant B, Thanner J. Radiostereometry of hip prostheses. Review of methodology and clinical results . Clin Orthop. 1997;344:94–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Gill RH, Valstar ER. The history and future of radiostereometric analysis . Clin Orthop. 2006;448:10–21. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224001.95141.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulouvaris P, Stafylas K, Sculco T, Xenakis T. Custom-design implants for severe distorted proximal anatomy of the femur in young adults followed for 4-8 years . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):203–10. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder L. Implant stability, histology, RSA and wear—more critical questions are needed. A view point . Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65(6):654–8. doi: 10.3109/17453679408994626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi AV. Jr., Mallory TH, Eberle RW, Mitchell MB, Lefkowitz MS, Williams JR. Failure of intraoperatively customized non-porous femoral components inserted without cement in total hip arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995;77(12):1836–44. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur SK, Mont MA, McCutchen JW. Intraoperative custom press-fit and standard press-fit femoral components in total hip arthroplasty. A comparison of surgery, charges, and early complications . Am J Orthop. 1996;25(7):486–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuijse MJ, Valstar ER, Kaptein BL, Nelissen RG. The Exeter femoral stem continues to migrate during its first decade after implantation: 10-12 years of follow-up with radiostereometric analysis (RSA) . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(2):129–34. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.672093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nysted M, Benum P, Klaksvik J, Foss O, Aamodt A. Periprosthetic bone loss after insertion of an uncemented, customized femoral stem and an uncemented anatomical stem . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(4):410–6. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.588860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbyhaug PO, Klaksvik J, Romundstad P, Aamodt A. Primary stability of custom and anatomical uncemented femoral stems: a method for three-dimensional in vitro measurement of implant stability . Clin Biomech. 2010;25(4):318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilliar RM, Lee JM, Maniatopoulos C. Observations on the effect of movement on bone ingrowth into porous-surfaced implants . Clin Orthop. 1986;208:108–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Ryd L, Onsten I. Accurate accuracy assessment: review of basic principles . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(1):106–8. doi: 10.1080/00016470052944017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RP, Clark JE. Uncemented press-fit total hip arthroplasty using the Identifit custom-molding technique. A prospective minimum 2-year follow-up study . J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):247–54. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Kulkarni R, Downes EM. The ABG hydroxyapatite-coated hip prosthesis: one hundred consecutive operations with average 6-year follow-up . J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):619–25. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrl SM, Nivbrant B, Nilsson KG. No adverse effects of submelt-annealed highly crosslinked polyethylene in cemented cups: an RSA study of 8 patients 10 years after surgery . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(2):148–52. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.652889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvik G. Roentgen stereophotogrammetry. A method for the study of the kinematics of the skeletal system . Acta Orthop Scand. 1989. pp. 1–51. (Suppl 232) [PubMed]

- Thien TM, Ahnfelt L, Eriksson M, Stromberg C, Karrholm J. Immediate weight bearing after uncemented total hip arthroplasty with an anteverted stem: a prospective randomized comparison using radiostereometry . Acta Orthop. 2007;78(6):730–8. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonino AJ, Romanini L, Rossi P, Borroni M, Greco F, Garciaaraujo C, et al. Hydroxyapatite-coated hip prostheses—Early results from an international study . Clin Orthop. 1995;312:211–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal BC, de Kramer BJ, Grimm B, Vencken W, Heyligers IC, Tonino AJ. Femoral fit in ABG-II hip stems, influence on clinical outcome and bone remodeling: a radiographic study. Arch OrthopTrauma Surg. 2008;128(10):1065–72. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viceconti M, Brusi G, Pancanti A, Cristofolini L. Primary stability of an anatomical cementless hip stem: a statistical analysis . J Biomech. 2006;39(7):1169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein M, Mouhsine E, Argenson JN, Rubin PJ, Aubaniac JM, Leyvraz PF. Three-dimensional computed cementless custom femoral stems in young patients: midterm follow up . Clin Orthop. 2005;437:169–75. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000163001.14420.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]