Abstract

Introduction

Optical magnification is an essential tool in the practice of pediatric surgery. Magnifying loupes are the most frequently used instrument, although their use often comes at the expense of neck pain experienced by the operating surgeon. Recent advances have led to the development of a compact video microscope (VITOM®; Karl Storz Endoscopy GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) that displays high-definition magnified images on a flat screen. This study was designed to evaluate VITOM as a potential substitute for loupes in complex open pediatric procedures and to explore VITOM as an effective intraoperative teaching modality for open surgery.

Subjects and Methods

Three surgeons used the VITOM II exoscope in 20 operations: 14 hypospadias repairs, 2 inguinal hernia repairs, 1 sacrococcygeal teratoma resection, 1 recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula repair, and 2 additional procedures. Surgeons, trainees, and surgical technicians subjectively evaluated image quality; surgeons evaluated handling of VITOM, degree of neck strain, and fatigue. Three midlevel surgical trainees assessed the VITOM potential for teaching value. Overall impressions of each group and consensus opinions were generated.

Results

All procedures were completed without complication. The consensus opinion of the entire group was that image quality was excellent. The surgeons found VITOM easy to use, and all agreed that neck strain and fatigue were reduced. Surgical trainees felt that VITOM imaging aided in their understanding of procedures and anatomy. Surgical technicians perceived improved operation flow through better visualization of the procedure.

Conclusions

VITOM provides excellent visualization of pediatric operations with improved surgeon comfort and may serve as a substitute for loupes. Secondarily, we found enhanced trainee learning and potential improvement in the flow of surgical procedures. Further study of VITOM with a larger sample size and validated tools is needed.

Introduction

Optical magnification is an essential tool in the practice of pediatric surgery and urology, as it allows us to accurately identify and define critical anatomic structures in our smallest patients. Loupes with ×2.5–×4.5 magnification are most frequently used, although in some circumstances such as hypospadias repair or pediatric liver transplantation, the operating microscope may be used.1–5 Although these magnifying instruments are essential to the optimal care of our patients, they often come at a detriment to the operating surgeon in the form of neck or back pain and fatigue. Furthermore, neck pain, back pain, and fatigue have been studied in multiple surgical disciplines,6–8 but these factors, however, have not yet studied among pediatric surgeons. Drawbacks of traditional magnifying loupes include poor neck posture and frequent head movement to refocus the view, in addition to the inability to share the magnified visual field with surgical residents and assistants.

Recent advances in imaging technology have led to the development of a high-definition (HD) compact video microscope (VITOM®; Karl Storz Endoscopy GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) to perform open surgery that requires magnification.9 The VITOM exoscope provides images of superb quality, 2–16 times magnification zoom, and good illumination that are displayed on large-format HD flat screens for viewing of the surgeon, assistants, and other operating room personnel. VITOM has been used extensively in neurosurgery and in one study was found to be equivalent to, and a much less expensive substitute for, the traditional operating microscope.10,11 It has also been used effectively in laryngeal surgery and colposcopy, where less magnification was required.12,13

The primary goal of this study was to apply the VITOM instrument to complex pediatric surgical and urological procedures and to evaluate it as a potential substitute for loupes. A secondary aim was to assess VITOM as an effective intraoperative teaching modality for open surgical cases.

Subjects and Methods

Three surgeons (P.K.F., A.L.F., and B.P.D.) used the VITOM II exoscope on a series of 20 pediatric patients undergoing a variety of surgical and urologic procedures at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (Los Angeles, CA) from February 2010 to December 2012. Each surgeon performed the standard operation and had the option of using either ×2.5 or ×3.5 magnifying loupes in addition to the VITOM exoscope for each operation evaluated. The equipment used in the study was the VITOM II exoscope (catalog number 20916025 DA) with an Image 1 H3-Z HD camera (catalog number 22220055-3) and table-mounted articulated stand (catalog number 28272 HC) (Karl Storz Endoscopy–America, El Segundo, CA). During the procedures, surgeons could view the HD VITOM images displayed on a 26-inch flat screen at a comfortable viewing distance and angle (Fig. 1). At the conclusion of each operation, the surgeon, the assistant (usually a midlevel surgical resident), and the surgical technologist were asked to subjectively evaluate the following:

FIG. 1.

The VITOM II exoscope. (A) VITOM II with Image 1 H3-Z high-definition camera and articulating stand. (B) Operating room set-up of VITOM II with 26-inch flat screen monitor.

Surgeon: (1) image quality, (2) comfort with the VITOM set-up and use, and (3) neck strain and fatigue during the operation

Assistant: (1) image quality and (2) potential value in teaching operative procedures

Surgical technologist: (1) image quality and (2) value in facilitating the operation flow

Responses were recorded and then subsequently discussed among the three surgeons, three residents, and three surgical technologists to generate overall impressions for each group and identify consensus opinions of the entire group.

Results

All 20 procedures were completed without intraoperative complications (Table 1). The VITOM was used throughout the entirety of each operation and was not dismantled prematurely during any operation.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Procedures Performed

| Patient number | Age (months) | Weight (kg) | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 9 | Hypospadias repair |

| 2 | 8 | 8.3 | Hypospadias repair |

| 3 | 9 | 9.7 | Hypospadias repair |

| 4 | 11 | 10.4 | Hypospadias repair |

| 5 | 43 | 13.2 | Hypospadias repair |

| 6 | 14 | 11.1 | Hypospadias repair |

| 7 | 5 | 7.6 | Hypospadias repair |

| 8 | 10 | 6.8 | Hypospadias repair |

| 9 | 9 | 10 | Hypospadias repair |

| 10 | 8 | 8.3 | Hypospadias repair |

| 11 | 10 | 10 | Hypospadias repair |

| 12 | 3 | 5.8 | Hypospadias repair |

| 13 | 9 | 8.7 | Hypospadias repair |

| 14 | 13 | 9 | Hypospadias repair |

| 15 | 88 | 21.2 | Ureteral reimplant |

| 16 | 1 (premature infant) | 1.4 | Inguinal hernia repair |

| 17 | 7 days (premature infant) | 1.1 | Central venous catheter placement |

| 18 | 1 day | 3.3 | Sacrococcygeal teratoma resection |

| 19 | 7 | 4.7 | Recurrent H-type TEF repair |

| 20 | 28 | 13.1 | Bilateral inguinal hernia repair |

TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula.

Consensus opinions

Image quality

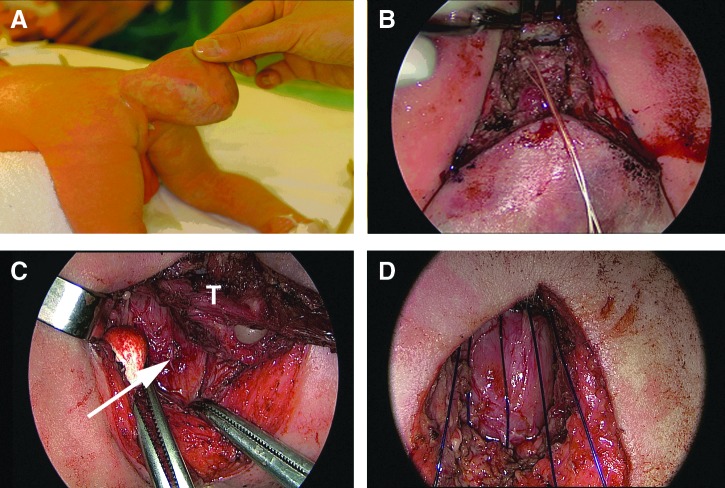

The consensus of all participants involved in the study was that the image quality was excellent with sharp resolution of fine anatomic detail. The group also thought that the zoom magnification of VITOM added significant versatility to visualizing structures of widely varying size (Figs. 2 and 3). Additionally, illumination was thought to be very good without evidence of tissue desiccation.

FIG. 2.

VITOM images of hypospadias repair: (A) elevation of the urethral plate to correct severe chordee; (B) extended urethroplasty with tubularization of the urethral plate; (C) completed urethroplasty; and (D) circumcision skin closure.

FIG. 3.

VITOM images of a newborn with a type I sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) resection: (A) SCT prior to resection; (B) division of the sacrococcygeal joint, taking the coccyx en bloc with the tumor; (C) dissection of the tumor (T) from the posterior rectal wall noted by arrow; and (D) pelvic floor reconstruction suturing the posterior levator muscles to the presacral fascia.

Impressions by group

Surgeons

All three surgeons found the set up of the VITOM with articulated stand was easy to learn. They found it took approximately 10 minutes to set up initially, but this decreased to ≤5 minutes after several uses. The group found that once the VITOM was initially positioned over the operative field, it required infrequent adjustments. During the operation, the VITOM magnification occasionally needed to be changed or required refocusing; however, all surgeons thought that these adjustments did not detract significantly from the natural progression of the procedure. They also found that the multiple degrees of freedom in the articulating stand accommodated for structures that were not perfectly horizontal in orientation. All surgeons noted a lack of stereotactic vision with VITOM, and they collectively agreed that it required adjustment, taking about two procedures to feel comfortable using it.

The surgeons thought that neck strain and fatigue were reduced compared with wearing magnifying loupes, and they attributed improved ergonomic positioning of the head and neck while viewing images on the flat screen. Specifically, the eldest of the three surgeons, who had a history of cervical disc disease, noted significantly less discomfort than similar procedures performed wearing extended-view ×3.5 loupes.

Assistants/residents

The three surgical residents felt strongly that the VITOM images on an HD flat screen greatly enhanced their visualization of the operations performed. Furthermore, they thought that this better visualization significantly aided in their understanding of the procedures and associated key steps, as well as overall surgical anatomy. They also thought that VITOM not only enhanced their individual education, but would also be beneficial for presentation of live or recorded procedures for future resident education.

Surgical technicians

Three surgical techs (none of whom use magnifying loupes) concurred that the images displayed using VITOM gave them markedly superior visualization of the operative field compared without using VITOM. They unanimously agreed that the improved visualization enabled them to follow the progression of the procedure better, enabling them to anticipate next steps, thereby enhancing flow and their efficiency during the procedure. They also noted that even with the articulating stand and VITOM positioned over the operative field, it did not impede the routine performance of their job functions (passing instruments and sutures).

Discussion

This preliminary study is the first applying VITOM for open surgical cases in pediatric surgery and urology. The most striking finding of the study was the consensus of all participants of the superb HD image quality and clear resolution of anatomic detail, which has been reported in previous studies in neurosurgery, otolaryngology, and gynecology.9,12–14 The VITOM imaging system lends itself well to neonatal and pediatric surgical cases by providing clear visualization of the operation to all operating room personnel, many of whom would typically not be able to see the small operative field because of limitations of space, lack of magnifying loupes, or both.

Back and neck pain among surgeons has been reported across many disciplines, especially in those fields often using the operating microscope or loupe magnification.6–8 As a group, the surgeons subjectively noted less neck strain and fatigue using VITOM compared with traditional magnifying loupes alone; however, this finding is limited by lack of objective measures to better quantitate these potential differences. Based on previous studies using VITOM, we speculate that the decreased neck strain and fatigue is the result of improved ergonomics throughout the operations that enabled the surgeon to stand straight upright for hours in a comfortable position, thereby decreasing the need to lean or bend the neck to maintain magnifying loupe focus.10,11

A related aspect that surgeons noted was that although the magnified image quality was thought to be excellent, there was a lack of stereoscopic vision. So in essence, when a surgeon is operating while viewing flat screen images, he or she is viewing a two-dimensional image, very similar to a laparoscope. However, this lack of three-dimensional visualization was compensated for by the large depth of field (1.2 cm) of VITOM, which decreased the need to refocus the image.10 In addition, all of the surgeons in this study had extensive experience with endoscopic surgery and adjusted after a few cases to the lack of stereopsis.

Teaching potential

As a group, trainees thought that the VITOM system markedly improved their visualization of the operations, thereby improving their understanding of the procedures and enhancing the teaching environment. A similar experience has been reported in a neurosurgery training program, with parallel constraints to pediatric surgery of small incisions and limited operative field.9,10 In addition, HD video documentation of some of the less frequently performed open procedures (specifically the recurrent H-type tracheosophageal fistula repair and sacrococcygeal teratoma) enabled a trainee to review the sequence of critical steps of these operations to prepare for future cases. It is interesting that it has been reported that with the widespread acceptance of endoscopic procedures in pediatric surgery and urology, less traditional open surgery is being performed.15 Hence, in some training programs, trainees may be exposed to significantly fewer open procedures than their predecessors a decade ago. One could imagine a future need for a video library of uncommon open neonatal and urologic procedures that might be a useful adjunct to existing compendia of endoscopic pediatric operations. With the magnification and image quality, the VITOM system would be well suited for such a task and may also be used for live demonstrations.

Operation flow

A somewhat unexpected finding was the positive impact that VITOM imaging made on the surgical technicians, all of whom both found it easier to follow the progression of operations and believed that it improved the flow of the procedures. Given the subjective nature of this assessment and the lack of comparison with identical procedures that did not use VITOM, there is a perception that operation flow may be improved. Furthermore, the set-up of the lightweight exoscope (<600 g) with standard connections to Karl Storz endoscopic components and articulating stand was easily learned and added about 5 minutes of operating time. Whether a potential improvement in operation flow may offset the small additional set-up time to significantly decrease overall operative time can only be determined through more rigorous study.

Limitations

Limitations of the study include small numbers of patients, participating surgeons, residents, and surgical technicians and the inherently subjective nature of the evaluation. Despite these drawbacks, the information gained through this exploratory study has enabled us to generate hypotheses as to how VITOM may be used to improve patient care through better visualization of anatomy with increased surgeon comfort (or rather reduced surgeon discomfort) and enhanced trainee teaching and potentially decrease operating room time and cost. In the near future we plan to study some of these hypotheses using validated survey tools in a larger sample size of patients with additional surgeons at other centers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Miller for administrative support and figure construction.

Author Contributions

P.K.F., A.L.F., and G.B. are responsible for study design. A.L.F., P.K.F., B.P.D., A.G., and J.A.W. are responsible for data acquisition. P.K.F., A.L.F., G.B., and A.G. are responsible for data analysis and interpretation. P.K.F. is responsible for drafting the manuscript. P.K.F., A.L.F., G.B., A.G., and B.P.D. are responsible for critical review and revision. P.K.F. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosure Statement

G.B. holds a U.S. patent (US PTO Application nos. 29/443, 031, 29/443,034, and 29/443,052) for VITOM basic methodology and is a paid consultant of Karl Storz Endoscopy GmbH. P.K.F., B.P.D., A.G., J.A.W., and A.L.F. have no personal financial or institutional interest in the device described in this article, nor did they receive financial compensation or honoraria in performance of this study.

References

- 1.Jarrett PM. Intraoperative magnification: Who uses it? Microsurgery. 2004;24:420–422. doi: 10.1002/micr.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert DA. Devine CJ., Jr Winslow BH. Horton CE. Getz SE. Microsurgical hypospadias repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:460–467. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198603000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wacksman J. Repair of hypospadias using new mouth-controlled microscope. Urology. 1987;29:276–278. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterman BJ. Renschler T. Cartwright PC. Snow BW. DeVries CR. Variables in successful repair of urethrocutaneous fistula after hypospadias surgery. J Urol. 2002;168:726–730. discussion 729–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarrera JV. Sinha P. Lobritto SJ. Brown RS., Jr Kinkhabwala M. Emond JC. Microvascular hepatic artery anastomosis in pediatric segmental liver transplantation: Microscope vs loupe. Transpl Int. 2004;17:585–588. doi: 10.1007/s00147-004-0782-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee A. Ryan WG. Rosen ES. Back pain in ophthalmologists. Eye (Lond) 1994;8:473–474. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babar-Craig H. Banfield G. Knight J. Prevalence of back and neck pain amongst ENT consultants: National survey. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:979–982. doi: 10.1258/002221503322683885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soueid A. Oudit D. Thiagarajah S. Laitung G. The pain of surgery: Pain experienced by surgeons while operating. Int J Surg. 2010;8:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamelak AN. Nobuto T. Berci G. Initial clinical experience with a high-definition exoscope system for microneurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:476–483. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000372204.85227.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirzadi A. Mukherjee D. Drazin DG, et al. Use of the video telescope operating monitor (VITOM) as an alternative to the operating microscope in spine surgery. Spine. 2012;37:E1517–E1523. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182709cef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mamelak AN. Drazin D. Shirzadi A. Black KL. Berci G. Infratentorial supracerebellar resection of a pineal tumor using a high definition video exoscope (VITOM®) J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:306–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlucci C. Fasanella L. Ricci Maccarini A. Exolaryngoscopy: A new technique for laryngeal surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:326–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vercellino GF. Erdemoglu E. Kyeyamwa S, et al. Evaluation of the VITOM in digital high-definition video exocolposcopy. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2011;15:292–295. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182102891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamelak AN. Danielpour M. Black KL. Hagike M. Berci G. A high-definition exoscope system for neurosurgery and other microsurgical disciplines: Preliminary report. Surg Innov. 2008;15:38–46. doi: 10.1177/1553350608315954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.te Velde EA. Bax NM. Tytgat SH, et al. Minimally invasive pediatric surgery: Increasing implementation in daily practice and resident's training. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:163–166. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9395-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]