Abstract

Cell culture systems are widely used for the investigation of in vitro immunomodulatory effects of medicines and natural products. Since many pharmacological relevant compounds are water-insoluble, solvents are frequently used in cell based assays. Although many reports describe the cellular effects of solvents at high concentrations, only a few relate the effects of solvents used at low concentrations. In this report we investigate the interference of three commonly used solvents: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethanol and β-cyclodextrin with five different cell culture systems. The effects of the solvents are investigated in relation to the cellular production of interleukin (IL)-6 or reactive oxygen species (ROS) after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. We show that DMSO above 1 % reduces readout parameters in all cell types but more interestingly the 0.25 and 0.5 % solutions induce inhibitory effects in some cell types and stimulatory effects in others. We also found that LPS induced ROS production was more affected than the IL-6 production in the presence of ethanol. Finally we showed that β-cyclodextrin at the investigated concentrations did not have any effect on the LPS induced IL-6 production and only minor effects on the ROS production. We conclude that the effects induced by solvents even at low concentrations are highly relevant for the interpretation of immunomodulatory effects evaluated in cell assays. Furthermore, these results show the importance of keeping solvent concentrations constant in serial dilution of any compound investigated in cell based assays.

Keywords: DMSO, Ethanol, β-cyclodextrin, IL-6 production, Reactive oxygen species, Immunomodulatory effects

Introduction

Cell culture systems incorporating cell lines or primary cells of human or murine origin are widely used for the investigation of in vitro immunomodulatory effects of medicines and natural products. These systems provide the possibility to investigate the influence of novel compounds on cellular functions [e.g. cytokine excretion, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), gene regulation and protein expression] with the complexity of functionally and structurally intact cells.

Predominantly, experiments with cell culture systems are performed in buffered saline or in growth medium. Therefore, water-soluble samples do not represent a problem with regards to solubility in the growth medium, while water-insoluble samples often require the inclusion of an extraneous solvent or additive to facilitate solubilization. Introduction of an extraneous solvent or additive to the growth medium will however alter the cellular environment and may therefore affect the outcome of the experiment.

Most papers that present results from cell culture experiments also provide data on the possible toxic effects of the used solvent. However, despite the fact that several authors report interactions of frequently used solvents with cellular based assays, it is seldom described how the applied concentrations of the solvents affect the actual readout.

In this report we investigate the interference of three commonly used solvents: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), β-cyclodextrin and ethanol with five different cell culture systems: peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), peripheral leukocytes, the human monocytic cell line Mono Mac 6 (MM6), the murine monocytic cell line RAW 264.7 and the HL-60 cell line differentiated to a neutrophil like cell type. The immunomodulatory effects induced by the solvents are investigated by stimulating the cells with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and comparing the cellular responses from cells incubated in the absence of solvents to the response from cells incubated with increasing concentrations of solvents. The effects induced by the three solvents on the response were assessed using either production of interleukin (IL)-6 or ROS as readout parameters. The ROS production was measured by luminol enhanced chemiluminescence and the cytokine production was quantified using a time resolved dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluoro immunoassay (DELFIA).

Materials and methods

Reagents

LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5, 263 pg/EU (Lonza, Visp, Switzerland) was dissolved in pyrogen free water and diluted with Hanks balanced salt solution with calcium and magnesium (HBSS; Gibco BRL—Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DMSO hybri-max (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), ethanol (Kemetyl A/S, Koege, Denmark) and β-cyclodextrin (Sigma Chemical Co.) were likewise diluted with HBSS. Luminol (5-Amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) (Across Organics—Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was dissolved in HBSS during constant stirring for 24 h and used at a final concentration of 283 μM. Human plasma was isolated from venous blood of a healthy volunteer collected in heparinised anticoagulation vacutainers (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Plasma was obtained by centrifugation of whole blood (1,000×g, 20 min) and stored at -80 °C until use. All buffers and reagents were purchased with a certificate of low endotoxin content or tested negative in our kinetic-turbidimetric LAL assay (detection limit < 0.01 EU/ml).

Experimental setup

Experiments were conducted with cultured cells or cells isolated from healthy volunteers. For the monocytic cells, cell suspensions were incubated with solvents at various concentrations and with LPS (0.5 EU/ml) for 20 h. The produced cytokines were quantified by DELFIA and compared to the control stimulation where no solvents were added. For the ROS measurements we either differentiated HL-60 cells with all-trans retinoic-acid (ATRA) to obtain cells with neutrophilic characteristics or used the leukocyte fragment of freshly drawn whole blood. To measure the immunomodulatory effect of the solvents, cells were subjected to increasing concentrations of the solvents and stimulated with LPS. The production of ROS was measured by luminol enhanced chemiluminescence and the results quantified as the area under the curve (AUC) from 0 to 180 min.

Cells were stimulated with solvents at the following concentrations: DMSO: 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 %, Ethanol: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 1 and 5 %, β-cyclodextrin: 0.1, 1, 10, 50 and 100 μg/ml.

Cell cultivation and isolation

Mono Mac 6

The human monocytic cell line Mono Mac 6 was acquired from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany) (ACC 124). The cells were cultured in pyrogen free RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) with 5 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biological industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel), 200 U/ml penicillin, 200 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 % glutamax, 1 % non essential amino acids (Gibco BRL, USA) and 1 % sodium pyruvate (Gibco BRL). The cells were incubated in humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2 and 95 % air at 37 °C. The medium was replaced twice weekly and the cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/ml.

HL-60

The HL-60 cell line was acquired from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) (CCL-240) and cultured in growth medium consisting of RPMI 1640 (Biological industries) supplemented with 10 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biological industries), 1 % glutamax (Gibco BRL), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were incubated in humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2, 95 % air at 37 °C and the culture medium was replaced twice a week. The cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/ml and the concentration was at all times kept below 1 × 106 cells/ml. The cells were used for a maximum of 25 passages after acquisition from ATCC. From the continuously growing cell culture, cells were collected for differentiation. To induce differentiation along the granulocytic pathway, cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1 μM all-trans retinoic-acid (ATRA; Fluka-Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were allowed to differentiate for 7 days without further renewal of culture medium or cell passage.

RAW 264.7

The RAW 264.7 cells ECACC (Salisbury, U.K.) (91062702) were cultivated in DMEM (D5546, Sigma) supplemented with 10 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biological industries), 1 % glutamax (Gibco BRL), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells are semi-adherent and were subcultivated before they reached confluency. With a cell-scraper the cells were loosened from the culture flask and subcultivated at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC)

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll separation. In short, whole blood was diluted 1:1 with 0.9 % pyrogen free saline. Ficoll-paque (3 ml) was transferred to a 11 ml centrifuge tube and 4 ml of whole blood was layered on top of the Ficoll-paque. After centrifugation (400×g, 40 min) the plasma layer was removed and the lymphocytes were isolated and washed twice with saline before they were resuspended in pyrogen free RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 5 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biological industries), 200 U/ml penicillin, 200 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 % glutamax, 1 % non essential amino acids (Gibco BRL) and 1 % sodium pyruvate (Gibco BRL) and standardised.

Leukocytes

Leukocytes were isolated from human whole blood after lysis of red blood cells and centrifugation. The red blood cell lysis buffer comprised of 0.826 g NH4Cl, 0.1 g KHCO3, and 0.0037 g EDTA. The reagents were dissolved in 100 ml pyrogen free water and filtrated through an Ultrasart D20 ultrafilter (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). For the isolation procedure 2.5 ml whole blood and 7.5 ml red blood cell lysis buffer was inserted carefully in a 11 ml centrifuge tube for 2 min. The cell suspension was then centrifuged (125×g, 10 min) and the pellet resusupended in 5 ml red blood cell lysis buffer. The centrifugation was repeated and the pellet was washed twice in prewarmed (37 °C) HBSS before the stock solution was standardised to 1 × 107 cells/ml.

Stimulation of cells

Mono Mac 6 cells were seeded at 4 × 105 cells/ml and incubated overnight in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium. The cells were then centrifuged (125×g, 5 min), resuspended in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium and standardised to 2 × 106 cells/ml. Equal volumes of test solution (solvent diluted with HBSS and 50 pg/ml LPS) and suspension (250 μl) were gently mixed and incubated for 20 h. The culture was then centrifuged (125×g, 10 min), the supernatants were isolated and the content of IL-6 determined.

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/ml and incubated overnight in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium. The supernatants were then discarded and the cells stimulated with 250 μl test solution (solvent diluted with HBSS and 50 pg/ml LPS) and 250 μl supplemented RPMI 1640 medium. After 20 h the supernatants were isolated and the content of IL-6 determined.

PBMCs were standardised to 2 × 106 cells/ml. Equal volumes of test solution (solvent diluted with HBSS and 50 pg/ml LPS) and cell suspension (250 μl) were gently mixed and incubated for 20 h. The cell culture was then centrifuged (125×g, 10 min), the supernatants were isolated and the content of IL-6 determined.

Leukocytes and differentiated HL-60 cells were standardised to 1 × 107 cells/ml and used for ROS experiments as described below.

Quantification of interleukin from PBMC and monocytic cell lines

Interleukin-6 determination

The IL-6 concentration was determined using DELFIA. The assay was conducted as described previously (Moesby et al. 2008). Linearity between fluorescence and the IL-6 concentration was observed within the concentration range 5–4,000 pg/ml. Each standard and test was analyzed in triplicate. For the murine cell line RAW 264.7 the same procedure was applied for the determination of murine derived IL-6 using monoclonal anti-mouse IL-6 capture antibody (2 μg/ml, 100 μl/well; MAB406, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), standards prepared from recombinant murine IL-6 (406-ML-005, R&D Systems) and biotinylated polyclonal rat anti-murine IL-6 antibody (100 ng/ml; 100 μl/well; BAF406, R&D Systems).

Quantification of ROS from isolated leukocytes and HL-60 cells

Production of ROS from isolated leukocytes and HL-60 cells was determined by luminol enhanced chemiluminescence (Timm et al. 2009). In short, the differentiated HL-60 cells were washed once in prewarmed (37 °C) HBSS, resuspended and standardised to 1 × 107 cells/ml and cells were used immediately hereafter. Isolated leukocytes were used within 30 min after the isolation procedure described above. Prior to measurements a reaction mixture was prepared in a white polystyrene LumiNuncTM96-Well Plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark), each well containing a final concentration of 5 × 105 differentiated HL-60 cells or leukocytes, 283 μM luminol and 2.5 % human plasma. The wells were supplemented with HBSS to a volume of 100 μl and allowed to equilibrate for 15 min at 37 °C prior to addition of 50 μl of LPS (100 pg/ml) and 50 μl of solvent or control solution (HBSS). The microplate was read as follows: 1 s/well (every second minute) for 180 min in an ORION II Microplate luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany) at 37 °C. The HL-60 cells and isolated leukocytes react to stimulation by releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) quantified by luminol enhanced chemiluminescence. The light emitted from the reaction was assessed as relative luminescence units per second (RLU/s). The results were quantified as the area under the curve (AUC) of continuous measurements for 180 min.

Statistics

For evaluation of the effects of the solvents compared to the control without addition of solvent we used ANOVA unless otherwise stated. We considered p ≤ 0.05 as significant.

Results

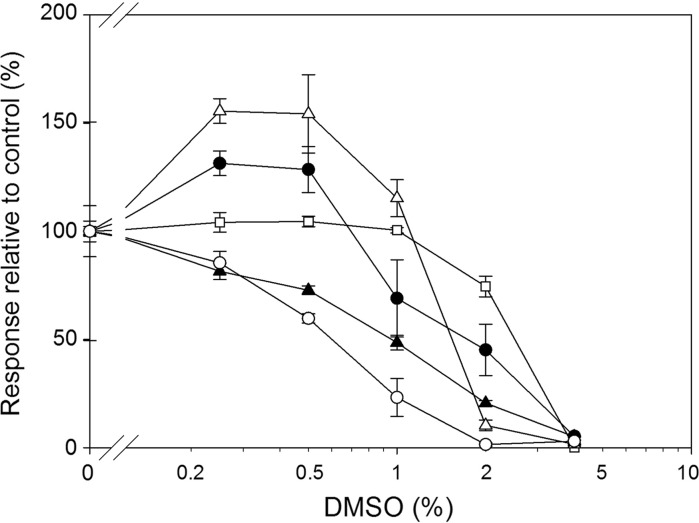

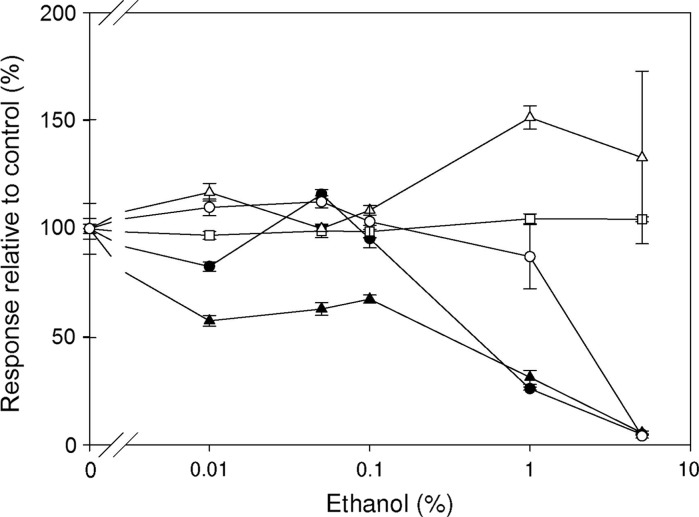

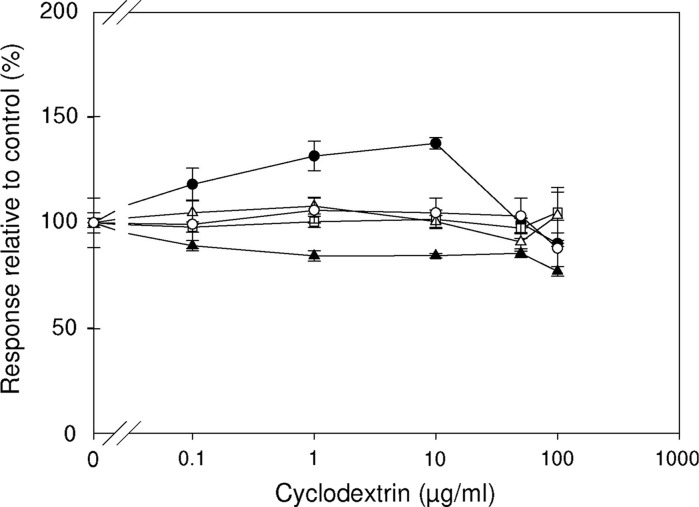

In the present study we examined the effects of solvents on stimulated cells in order to test the hypothesis whether solvents would either abrogate or enhance exogenous responses. To stimulate the cells we used LPS at a concentration that induces sub-maximal responses according to our standard curves for the five cell types (data not shown). We have displayed the results according to the solvent and normalised responses from all cell types to the activation induced by the LPS stimulation without any solvent present. Therefore the percentage displayed in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 corresponds to the activation induced or abrogated by the solvents for the various cell types.

Fig. 1.

Effects of DMSO. Influence of DMSO concentration (0.25–4 %) on the LPS induced ROS production in HL-60 cells (closed circles) and isolated leukocytes (closed triangles) and on the IL-6 production in isolated PBMCs (open squares), Mono Mac 6 cells (open triangles) and RAW 264.7 cells (open circles). All responses were normalized to the LPS induced responses of the respective cells incubated in HBSS in the absence of DMSO (=100 %). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3)

Fig. 2.

Effects of ethanol. Influence of ethanol concentration (0.01–5 %) on the LPS induced ROS production in HL-60 cells (closed circles) and isolated leukocytes (closed triangles) and on the IL-6 production in isolated PBMCs (open squares), Mono Mac 6 cells (open triangles) and RAW 264.7 cells (open circles). All responses were normalized to the LPS induced responses of the respective cells incubated in HBSS in the absence of DMSO (=100 %). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3)

Fig. 3.

Effects of β-cyclodextrin. Influence of β-cyclodextrin concentration (0.1–100 μg/ml) on the LPS induced ROS production in HL-60 cells (closed circles) and isolated leukocytes (closed triangles) and on the IL-6 production in isolated PBMCs (open squares), Mono Mac 6 cells (open triangles) and RAW 264.7 cells (open circles). All responses were normalized to the LPS induced responses of the respective cells incubated in HBSS in the absence of DMSO (=100 %). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3)

Effects of DMSO

The effect of DMSO is recognisable for all cell types (Fig. 1). At 4 % DMSO the responses were reduced by more than 90 % in all cellular systems tested. The cells most sensitive to DMSO were the isolated leukocytes and the RAW 264.7 cells. The ROS production of leukocyte was significantly affected by all concentrations of DMSO. The RAW 264.7 cells were also affected by DMSO concentrations above 0.5 % as evaluated by a ratio paired t test. However, only concentrations above 1 % resulted in significant differences in the IL-6 production based on the ANOVA test. For the PBMCs, HL-60 and the Mono Mac 6 cells the release of ROS or IL-6 was significantly reduced at concentrations above 1 %. For the Mono Mac 6 cells DMSO concentrations of 0.5 and 0.25 % significantly increased the IL-6 release. The same tendency was observed for the HL-60 cells where an increase in the ROS production could be recognised (p values of 0.0507 and 0.0533 for 0.5 and 0.25 %, respectively) when compared to control.

Effects of ethanol

Cellular sensitivity towards ethanol is more pronounced in the LPS induced ROS production of leukocytes and HL-60 cells than in the IL-6 production of the mononuclear cells (Fig. 2). At concentrations of up to 5 % ethanol the IL-6 release from isolated PBMC and Mono Mac 6 cells was not significantly different from the control. In the murine monocytic cell line RAW 264.7 a tolerance was also observed up to 1 % ethanol but at 5 % the response was reduced by more than 95 % compared to the control. All concentrations of ethanol significantly reduced the ROS production of isolated Leukocytes and likewise the ROS production of HL-60 cells was significantly reduced at concentrations of 1 and 5 % of ethanol.

Effects of β-cyclodextrin

β-cyclodextrin at the investigated concentrations did not have any effect on the LPS induced IL-6 production from monocytoid cells (Fig. 3). For the HL-60 cells a significant activation by cyclodextrin was observed at concentrations of 1 and 10 μg/ml. In the isolated leukocytes a slight but significant reduction of the ROS production was observed at all concentrations of cyclodextrin.

Discussion

A common concern when introducing extraneous solvents into cellular systems is the general cytotoxic effect of the solvent. It is therefore common practice to test the viability of the treated cells in a MTT assay (Mosmann 1983) or by using the trypan blue dye exclusion test (Strober 2001). However, usually only the highest concentration of the solvent is tested and conclusions on cell toxicity are drawn on this basis. However, as the results presented here display, that this is not always sufficient since the solvents may influence the outcome of the experiment even though used at concentrations far below those that would induce cytotoxicity.

DMSO is commonly used as solvent for water-insoluble samples to be tested in bioassays including cellular based assays. In a study by Forman et al. DMSO was found to exhibit a cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells at concentrations above 2 % and an inhibitory effect on cell growth at concentrations below 1 % (Forman et al. 1999). In another study DMSO was found to reduce the amount of measured superoxide production from primary neutrophils, eosinophils lymphocytes and monocytes at concentrations above 1 % (Kahler 2000). Our findings partly support this since the cellular functions in regards to IL-6 and ROS production in Mono Mac 6 cells, HL-60 cells and PBMC was not significantly reduced by 1 % DMSO. Isolated leukocytes and RAW 264.7 cells were however both negatively affected at these concentrations. An interesting finding is that concentrations of 0.25 and 0.5 % DMSO exerted a stimulatory effect on the responses from Mono Mac 6 cells. This tendency could also be observed using HL-60 cells. However the same concentrations of DMSO reduced the response from RAW 264.7 and isolated leukocytes (Fig. 1). Only the response from isolated PBMC’s seemed to be unaffected at these concentrations of DMSO. This may be important since dilutions of samples containing a solvent are seldom considered problematic. Therefore, serial dilutions of a sample (without equimolar concentrations of DMSO in the diluents) may in fact elicit an immunomodulatory response which could falsely be concluded to originate from the sample tested and not due to alterations of the solvent concentration. Thus, 1 % DMSO seems to be a critical concentration since lower concentrations will result in increased cellular activation while higher concentrations will exert inhibitory effects. Our results seem to indicate that different cell types respond very differently to DMSO at various concentrations in connection to various stimuli; this also seems to be the case in other studies (Xing and Remick 2005; Hollebeeck et al. 2011).

Ethanol is often used as a solvent for plant extracts and hereof derived components for testing in bioassays (Zhijun 2008). There have been many studies indicating a general immunosuppressive effect of ethanol and other alcohols (Nair et al. 1990; Szabo 1999; Desy et al. 2010, 2008). Investigating the effects of ethanol on HeLa cells it was found that concentrations of 5 % and above compromised the cell viability (Forman et al. 1999). The influence of ethanol on cell viability of RAW 264.7 cells was evaluated by the trypan blue staining method and it was found that the cell viability was not affected at concentrations up to 600 mM (~2.8 %) (Wakabayashi and Negoro 2002). In the present study RAW 264.7 cells were found to tolerate concentrations of ethanol of 1 % while the response was greatly attenuated at 5 %. Interestingly, concentrations of ethanol up to 5 % did not affect the response of Mono Mac 6 cells. In contrast to this, all tested concentrations of ethanol (0.01–5 %) significantly reduced the response from isolated leukocytes (Fig. 2).

Cyclodextrins are cyclic oligosaccharides (mainly made up of six, seven or eight dextrose units; α, β and γ) which can form inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drug molecules and hereby enhance the aqueous solubility of these compounds (Stella and He 2008). Irie and Uekama have reviewed the cellular interactions of cyclodextrins and found that they were able to induce shape changes of membrane invagination on human erythrocytes and at higher concentrations induce lysis (Irie and Uekama 1997). Furthermore, the hemolytic activity of cyclodextrins correlates with their ability to form inclusion complexes with cell membrane lipids which hereby are removed causing the cell membrane to become unstable and in turn cause cell lysis. The cytolytic effect of cyclodextrins have also been observed in other cells lines such as human skin fibroblasts, intestinal cells, and E. coli, suggesting that cyclodextrin-induced cell lysis is not cell type specific (Irie and Uekama 1997). Testing β-cyclodextrin at concentrations of 0.1–100 μg/ml we observed that only the response from isolated leukocytes was significantly reduced. Contrary to this β-cyclodextrin at concentrations of 1–10 μg/ml significantly augmented the response from HL-60 cells while no effect was observed for the response from isolated PBMC’s, Mono Mac 6 and RAW 264.7 cells for the tested concentration range (Fig. 3).

In this study we observed a tolerance of the monocytic cells and cell lines towards ethanol. This tolerance is contradictory to our own and others’ previous findings that reported great sensitivity of monocytic cells towards ethanol. One explanation is that the matrix affects the cellular tolerance. In our previous findings we have used pyrogen free water as matrix for studies of solvent interactions. However, in the experiments of the present study we have used a buffered salt solution (HBSS), and therefore suspect the matrix to be partly responsible for this increased tolerance in regards to previous findings. Control experiments showed that when using pyrogen free water as matrix the 5 % ethanol solution reduced the IL-6 production of the Mono Mac 6 cells (by approximately 90 %). The 1 % ethanol solution reduced the production by 25 % (data not shown) this pronounced reduction was however not observed in the HBSS matrix emphasising the relevance of the solvents used but also of the matrix.

Several compounds are known to scavenge reactive oxygen species. Consequently the observed effects of ethanol and DMSO on the isolated leukocytes and HL-60 cells may be due to enhanced scavenging of the solvents at high concentrations. However control experiments in HL-60 cells showed that the concentrations of DMSO and ethanol that inhibited the ROS production also inhibited IL-8 production of HL-60 cells, suggesting a cellular effect of the solvents rather than a scavenging effect (data not shown).

Concluding remarks

The results reported here emphasize the importance of keeping equimolar solvent concentrations between test and control experiments even at very low concentrations. Furthermore we conclude that not only should cell based assays be validated with regards to cytotoxic effects of solvents used but also validated in relation to the effects of solvents on measurements of cellular responses as well as the matrix they are tested in. Therefore, when testing serial dilutions of novel compounds in cellular assays solvent concentrations should always remain the same even though the concentrations may not be cytotoxic. Furthermore it should be noted that results obtained with solvent interactions in one cell type cannot be transferred to other cell types.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Ms. Janne Møgelhøj Colding and Ms. Betina Schøler.

Footnotes

Michael Timm and Lasse Saaby: Contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Michael Timm, Phone: +45-35-336201, FAX: +45-35-336020, Email: mt@farma.ku.dk.

Lasse Saaby, Email: las@farma.ku.dk.

Lise Moesby, Email: lm@farma.ku.dk.

Erik Wind Hansen, Email: ewh@farma.ku.dk.

References

- Desy O, Carignan D, Caruso M, de Campos-Lima PO. Immunosuppressive effect of isopropanol: down-regulation of cytokine production results from the alteration of discrete transcriptional pathways in activated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:2348–2355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desy O, Carignan D, Caruso M, de Campos-Lima PO. Methanol induces a discrete transcriptional dysregulation that leads to cytokine overproduction in activated lymphocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2010;117:303–313. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S, Kas J, Fini F, Steinberg M, Ruml T. The effect of different solvents on the ATP/ADP content and growth properties of HeLa cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 1999;13(11–15):3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(1999)13:1<11::aid-jbt2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeeck S, Raas T, Piront N, Schneider YJ, Toussaint O, Larondelle Y, During A. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) attenuates the inflammatory response in the in vitro intestinal Caco-2 cell model. Toxicol Lett. 2011;206:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T, Uekama K. Pharmaceutical applications of cyclodextrins.3. Toxicological issues and safety evaluation. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:147–162. doi: 10.1021/js960213f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CP. Evaluation of the use of the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide in chemiluminescent studies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2000;26:626–633. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moesby L, Timm M, Hansen EW. Effect of moist 370 heat sterilisation on the pyrogenicity of cell wall components from Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2008;35:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair MP, Kronfol ZA, Schwartz SA. Effects of alcohol and nicotine on cytotoxic functions of human lymphocytes. Clin Immunol Immnopathol. 1990;54:395–409. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90053-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella VJ, He Q. Cyclodextrins. Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36:30–42. doi: 10.1177/0192623307310945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober W (2001) Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol Appendix 3, A.3B.1–A.3B.2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Szabo G. Consequences of alcohol consumption on host defence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:830–841. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm M, Madsen AM, Hansen JV, Moesby L, Hansen EW (2009) Assessment of total inflammatory potential of bioaerosols using a granulocyte assay. Appl Environ Microbiol 75(24):7655–7662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi I, Negoro M. Mechanism of inhibitory action of ethanol on inducible nitric oxide synthesis in macrophages. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Remick DG. Mechanisms of dimethyl sulfoxide augmentation of IL-1 beta production. J Immunol. 2005;174:6195–6202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhijun L. Preparation of botanical samples for biomedical research. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8:112–121. doi: 10.2174/187153008784534358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]