Abstract

Enzyme mutagenesis is a commonly used tool to investigate the structure and activity of enzymes. However, even minute contamination of a weakly active mutant enzyme by a considerably more active wild-type enzyme can partially or completely obscure the activity of the mutant enzyme. In this work we propose a theoretical approach using reaction timecourses and initial velocity measurements to determine the actual contamination level of an undesired wild-type enzyme. To test this method, we applied it to a batch of the Q215A/R235A double-mutant of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae that was inadvertently contaminated by the more active wild-type OMPDC from Escherichia coli. The enzyme preparation showed significant deviations from the expected kinetic behavior at contamination levels as low as 0.093 mol%. We then confirmed the origin of the unexpected kinetic behavior by deliberately contaminating a sample of the mutant OMPDC from yeast that was known to be pure with 0.015% wild-type OMPDC from E. coli and reproducing the same hybrid kinetic behavior.

Keywords: Enzyme Purity, Enzyme Kinetics

Introduction

Enzyme kinetics is an important tool in understanding how enzymes are able to so successfully catalyze an incredibly broad range of chemical reactions. Knowing the fundamental kinetic parameters associated with both the overall enzymatic reaction and the individual mechanistic steps of the reaction can aid in the knowledge of how the enzyme is able to effect such efficient catalysis. The steady-state kinetic parameters are usually determined using Michaelis-Menten kinetics[1]. Eq. 1 is the Michaelis-Menten equation. v is the observed initial velocity of the reaction. It is equivalent to either the initial rate of product formation, d[P]/dt, or the initial rate of substrate consumption, −d[S]/dt. [E] and [S] give the concentration of enzyme and substrate, respectively. kcat is a first-order rate constant which represents the maximal turnover number for the enzyme. Km, also known as the Michaelis constant, is the substrate concentration at which the enzyme is forming product at half of its maximal rate. It also gives an idea of how much substrate is needed in order to saturate the enzyme as the enzyme will be saturated when [S] ≫ Km. The ratio of the parameters, kcat/Km, gives a second-order rate constant that can be used as a measure of an enzyme’s overall efficiency in carrying out a particular catalysis. The usual experimental approach is to measure the initial velocity of either product formation or substrate consumption for several substrate concentrations, and fit this data to eq. 1 to provide the kinetic parameters kcat and Km.

| (1) |

Under conditions where substrate concentration is less than ~10% of Km, an approximation is made that the [S] term in the denominator of eq. 1 can be ignored, reducing the Michaelis-Menten equation to eq. 2. Of note is that the initial velocity of the reaction is now directly proportional to substrate concentration, resulting in a first-order decay of the substrate. The observed first-order rate constant, kobs, is related to kcat/Km by eq. 3. Thus by plotting a timecourse of reaction progress at sufficiently low substrate concentration, the second-order rate constant, kcat/Km, can be determined directly. However this approach does not allow for the determination of kcat or Km individually. The two experimental approaches of measuring initial velocities at many substrate concentrations and observing the timecourse of reaction progress at low initial substrate concentrations provide complementary techniques of determining kcat/Km for an enzyme. Ideally, both would be utilized so that a timecourse of reaction progress could be used as an internal check of kcat/Km for the enzymatic catalysis determined from initial velocity experiments.

| (2) |

| (3) |

However if the enzyme of interest has been contaminated with another, more active enzyme that catalyzes the same chemical reaction, the kinetics could become more complicated. This can commonly be seen when the enzymes are prepared by overexpressing them from E. coli which contains its own version of the enzyme. A wild-type enzyme obscuring the reactivity of a mutant enzyme with lower activity has been reported previously for several enzymes, including triosephosphate isomerase[2], β-galactosidase[3], and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase[4]. In these cases, the mutants of the studied enzymes were so inactive towards catalysis that small amounts of highly active wild-type enzymes were responsible for the entirety of the observed enzymatic activity. The kinetic parameters that were observed in these cases were inconsistent with other kinetic measurements, or the chemical knowledge of what effect the mutations should have, for instance predicting that mutating critical residues in the active site would have no effect on the rate of catalysis. The primary difference compared to the experimental results described in this work is that our contaminating enzyme contributed some, but not all, of the observed catalytic activity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Orotidine 5′-monophosphate (OMP) was available from our earlier studies[5–8]. Water was from a Milli-Q Academic purification system. All other chemicals were reagent grade or better and were used without further purification. Wild-type orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScOMPDC) and Escherichia coli (EcOMPDC) were available from earlier studies[5, 8, 9]. The protein sequence of ScOMPDC differs from the published sequence for wild-type yeast OMPDC by the following mutations: S2H, C155S, A160S, and N267D[5, 9]. Except for the C155S mutation, the sequence is the same as that observed in the published crystal structure of wild-type ScOMPDC. The C155S mutation increases the stability of the protein, but does not affect the kinetic parameters or the overall structure of the enzyme[10]. The batch of ScOMPDC containing the Q215A/R235A double mutation was prepared according to the method given in our earlier studies [5, 8, 9] although the batch prepared for the current work was shown to be contaminated by ca. 0.09 mol% of wild-type EcOMPDC from the E. coli host used for overexpression of the mutant yeast enzyme (vide infra).

Preparation of Solutions

Solution pH was determined at 25 °C using an Orion Model 720A pH meter equipped with a Radiometer pHC4006-9 combination electrode that was standardized at pH 7.00 and 10.00 at 25 °C. Stock solutions of orotidine 5'-monophosphate (OMP) were adjusted to pH 6 – 7 and stored in small aliquots at −20 °C. The concentration of OMP in stock solutions was determined from its absorbance in 0.1 M HCl at 267 nm using ε = 9430 M−1 cm−1 [11].

Determination of kcat, Km, and kcat/Km for decarboxylation of orotidine 5'-monophosphate

Samples of mutant yeast OMPDCs that had been stored at −80 °C were defrosted and extensively dialyzed at 4 °C with 5 mM MOPS (50% free base) pH 7.1 at I = 0.05 (NaCl). The concentration of OMPDC in the stock solution was determined from its absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 29,910 M−1 cm−1, calculated using the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy server[12].

Second-order rate constants kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) for decarboxylation of OMP catalyzed by OMPDC were determined in 10 – 30 mM MOPS (50% free base) at pH 7.1, 25 °C and I = 0.105 (NaCl). Initial velocities of decarboxylation of OMP, vo (M−1 s−1), were determined spectrophotometrically by following the decrease in absorbance at 279 nm (Δε= −2400 M−1 cm−1), 290 nm (Δε = −1620 M−1 cm−1) or 295 nm (Δε = −842 M−1 cm−1)[5, 6 ]. The value of kcat/Km was obtained from the observed first-order rate constant, kobs (s−1), for the complete reaction of OMP at [OMP]o ≪ Km, monitored spectrophotometrically at 279 or 290 nm, using the relationship, kcat/Km = kobs/[E] (eq. 3). Values of kcat and Km were individually obtained from a Michaelis-Menten plot of initial velocity versus [OMP] with initial OMP concentrations ranging from 100–2000 μM, monitored spectrophotometrically at 279, 290, or 295 nm using the relationship v=kcat[E][OMP] / (Km+[OMP] ) (eq. 1).

Theory

We simulated the behavior of a mixture of a large amount of poorly active mutant enzyme and a much smaller amount of highly active wild-type enzyme. If the assumption is made that in a mixture of enzymes each enzyme will behave independently (as opposed to cross-dimerization or some other interaction), then the overall initial velocity of reaction will be the sum of the initial velocities for each enzyme (eq. 4). The initial velocities of reaction contributed by wild-type and mutant enzymes, vwt and vmut, will be given by the Michaelis-Menten expression (eq. 1), corrected for the fraction of either wild-type or mutant enzyme present, fwt or fmut. If the wild-type enzyme is present in trace amounts, the approximation is made that fmut = 1. Eq. 5 is derived by taking the absolute velocity of reaction due to mutant enzyme at any substrate concentration, and scaling it by dividing by the maximum possible velocity for this mixture of wild-type and mutant enzymes, kcatwtfwt[E] + kcatmut[E]. The analogous equation for the scaled velocity of reaction due to the wild-type enzyme is not shown. Eq. 6 gives the fractional velocity of reaction due to the mutant enzyme, by taking the velocity of reaction catalyzed by mutant enzyme at any given substrate concentration, and dividing by the total observed velocity of reaction catalyzed by the mixture of the two enzymes at that specific substrate concentration. Again, the analogous equation for the fractional velocity of reaction by wild-type enzyme is not shown. Note that while the absolute velocity of reaction will depend on the total enzyme concentration, eqs. 5 and 6 define ratios of velocities and are not dependent on the enzyme concentration.

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

A mixture of wild-type and mutant enzymes can be divided into three classes. In class 1, the contamination is so minor, or the mutant enzyme is sufficiently active that the observed activity results essentially entirely from the mutant enzyme. In class 2, the contamination is so severe, or the mutant enzyme is sufficiently inactive, that the observed activity results essentially entirely from the wild-type enzyme. In class 3, the contamination is moderate and the resultant observed activity comes from both the wild-type and mutant enzymes in similar proportions. Because classes 1 and 2 will show the expected kinetic behavior of pure mutant and pure wild-type enzymes, respectively, we will focus on class 3 (moderate contamination) for the remainder of this manuscript.

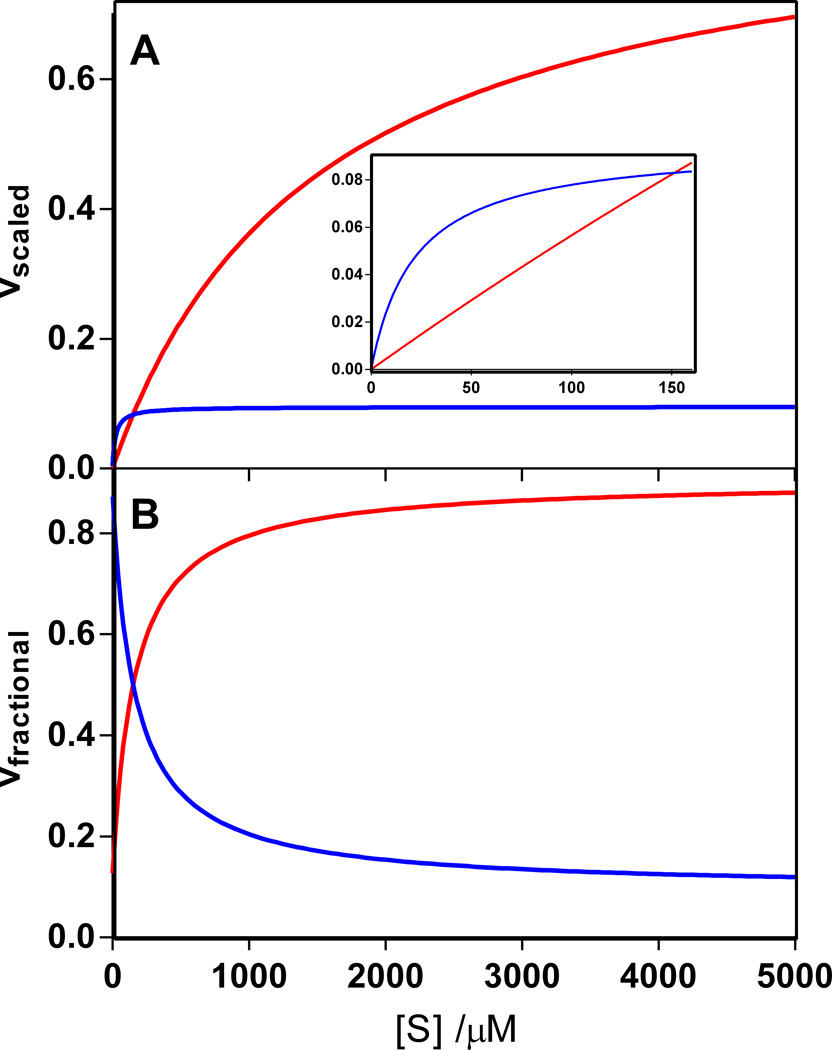

Full reaction timecourses are generally carried out in the regime where the enzyme shows first-order behavior, that is, [S]≪ Km.(Eq. 2). In contrast, initial velocity studies are carried out over a full range of substrate concentrations both above and below Km for the enzyme. Therefore we consider the effect of contamination over a wide range of substrate concentrations. Figures 1 – 3 show the relative contributions from both the wild-type and mutant enzymes under each of the three classes described above. In all three cases, the absolute activity of each enzyme increases with [S]. However, in the case that Kmwt < Kmmut, the wild-type enzyme will become saturated before the mutant enzyme. This assumption holds true for many enzymes, including cytochrome P450 BM-3 [13] and chorismate mutase [14]. This assumption holds true for most of the enzymes that our group has investigated. In figure 1, nearly all of the activity is due to the mutant enzyme except at the lowest [S]. In figure 2, nearly all of the activity is due to the wild-type enzyme, though there is marginal contribution from the mutant enzyme at the highest [S]. Figure 3 shows a hybrid behavior. When [S] < 150 μM, most of the activity is due to the wild-type enzyme. When [S] > 150 μM, most of the activity is due to the mutant enzyme. The maximum and minimum fractional contributions of mutant enzyme to the overall velocity can be determined by taking the limit of eq. 6 when the initial substrate concentration is very low (minimum contribution of mutant enzyme) or very high (maximum contribution of mutant enzyme). When [S] ≫ Km for both the wild-type and mutant enzymes, both enzymes will be saturated and the fraction of reaction caused by each enzyme will be based on their relative kcat values. When [S] ≪ Km for both enzymes, both enzymes will show first-order reactions and the fraction of reaction caused by each enzyme will be based on their relative kcat/Km values. Another way to put this is that kinetic experiments at low [S] such as reaction timecourses are especially sensitive to enzyme contamination. These experiments also allow a convenient means to determine the actual level of contamination.

Figure 1.

Simulated behavior of mutant enzyme with minor contamination of wild-type enzyme. kcatwt = 14 s−1; kcatmut = 1 s−1; Kmwt = 22 μM; Kmmut = 1000 μM and the contamination level is 0.05 mol%. (A) Velocities for the mutant enzyme (red) and the wild-type enzyme (blue) scaled by the maximum possible velocity for this mixture of enzymes. (B) Fractional velocity due to mutant enzyme (red) and wild-type enzyme (blue).

Figure 3.

Simulated behavior of mutant enzyme with moderate contamination of wild-type enzyme using the actual kinetic parameters those of EcOMPDC and mutant ScOMPDC (Table 1). kcatwt = 14 s−1; kcatmut = 0.02 s−1; Kmwt = 22 μM; Kmmut = 1500 μM and the contamination level is 0.015 mol%. (A) Velocities for the mutant enzyme (red) and the wild-type enzyme (blue) scaled by the maximum possible velocity for this mixture of enzymes. Inset: Enlargement of the graph for substrate concentrations less than 150 μM. (B) Fractional velocity due to mutant enzyme (red) and wild-type enzyme (blue).

Figure 2.

Simulated behavior of mutant enzyme with major contamination of wild-type enzyme. kcatwt = 14 s−1; kcatmut = 0.002 s−1; Kmwt = 22 μM; Kmmut = 2000 μM and the contamination level is 0.05 mol%. (A) Velocities for the mutant enzyme (red) and the wild-type enzyme (blue) scaled by the maximum possible velocity for this mixture of enzymes. (B) Fractional velocity due to mutant enzyme (red) and wild-type enzyme (blue).

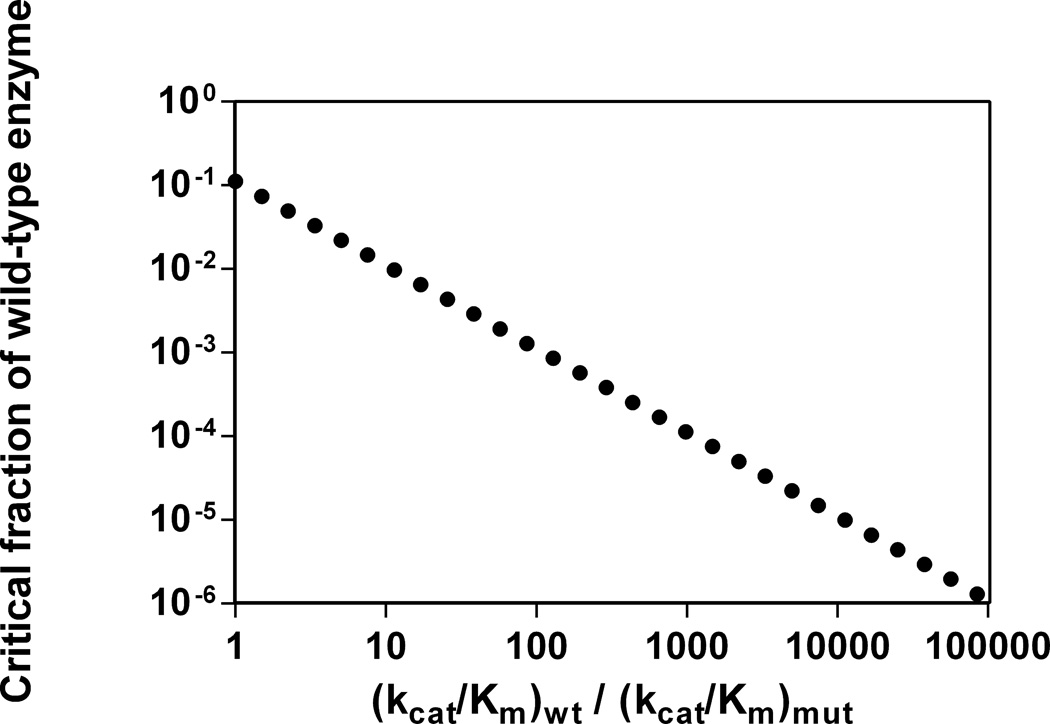

For the relatively low [S] utilized in full-reaction timecourses, the wild-type enzyme will show the majority of the activity. If [S] is lower than Km for the mutant, but higher than Km for the wild-type enzyme, the timecourse will begin with a region of zero-order behavior. Once [S] has decayed to a value lower than Km for both enzymes, both enzymes will show first order behavior and the observed reaction timecourse will be first-order, albeit with a spuriously large observed second-order rate constant based on the full activity for the wild-type enzyme being “diluted” by the considerably less active mutant enzyme. Eq. 7, gives the observed second-order rate constant, (kcat/Km)obs, as a weighted sum of the second-order rate constants for wild-type enzyme (kcat/Km)wt and mutant enzyme (kcat/Km)mut. Again making the assumption that fmut = 1 and rearranging eq. 7 gives eq. 8, the fraction of wild-type enzyme present as a function of the observed and true second-order rate constants. If authentic kinetic parameters for both the wild-type and mutant enzyme are known, the level of contamination can be determined. If an experiment requires at least 90% of the observed activity to be caused by the mutant enzyme at any [S], Figure 4 shows the maximum acceptable level of wild-type contamination based on the relative values of kcat/Km for each enzyme.

| (7) |

| (8) |

Figure 4.

Maximum acceptable enzyme contamination for a given ratio of kcat/Km for the wild-type and mutant enzymes. Each point indicates the contamination of the wild-type enzyme where at most 10% of that activity will be due to the wild-type enzyme.

For moderate enzyme contamination (class 3), the mutant enzyme will dominate the activity for sufficiently high values of [S]. If the [S] for which the mutant enzyme dominates is still below the Km value of the mutant, then initial velocity plots in that range will not show any observed saturation. Initial velocity plots will therefore predict a large Km for the enzyme, which is in contradiction to the results seen from the initial timecourses. Our model allows these contradictory results to be explained based on how the relative impact of the contamination changes with [S]. We now turn to a specific enzyme to confirm if moderate enzyme contamination is capable of showing the predicted kinetic effects.

Results and Discussion

We are interested in the enzyme orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC). This enzyme catalyzes the decarboxylation of orotidine 5’-monophosphate (OMP) to form uridine 5’-monophosphate (UMP, Scheme 1), a crucial reaction in the biosynthesis of other nucleotides such as cytidine monophosphate and thymidine monophosphate. OMPDC is one of the most efficient enzymes known, capable of accelerating the decarboxylation reaction by a factor of 1017 compared to the uncatalyzed reaction, while not requiring any metal ions or cofactors[15]. Several groups have probed the mechanistic details of just how OMPDC is capable of such a catalytic feat[15–18]. Based on previous experiments in our group, the mechanism of the decarboxylation involves the formation of a high-energy vinyl carbanion that is stabilized by the enzyme (Scheme 1)[19–22].

Scheme 1.

Part of our approach to studying OMPDC is using different enzymatic mutants in order to determine which amino acid residues are critical for the decarboxylation reaction, either by stabilizing the carbanion intermediate directly or indirectly interacting with a nonreacting portion of the substrate such as the phosphate group. In OMPDC from baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), two of these key residues are glutamine-215 and arginine-235 (Q215 and R235), both of which interact with the phosphate group of OMP[23]. Both glutamine and arginine can form hydrogen bonds between the NHs at the end of their side chains and the phosphate oxygens. One of the mutants we investigated was the Q215A/R235A double mutant of OMPDC from yeast (“mutant ScOMPDC”), where the key glutamine and arginine had been replaced with alanine residues that are incapable of forming these hydrogen bonds. Based on data from the Q215A and R235A single mutants of ScOMPDC, we expected the Q215A/R235A double mutant to have a Km value of at least 1000 μM, if not considerably larger [5, 6]. The initial substrate concentration in the timecourse of OMP decarboxylation was 27 μM, but to our surprise, the timecourse of OMP decarboxylation was not first-order at the beginning of the reaction (figure 5), instead appearing to be closer to zero-order at the beginning of the timecourse with a later transition to pure first-order behavior. Zero-order behavior is indicative of an enzyme that is saturated with substrate, meaning that Km must be smaller than 27 μM for Q215A/R235A mutant ScOMPDC. However the Michaelis-Menten plot of initial velocities (figure 6) revealed no apparent enzyme saturation when OMP concentrations of up to 500 μM were used, implying that Km was considerably larger than 500 μM. The complete reaction timecourse of 27 μM OMP and initial reaction velocities when up to 500 μM of OMP were used are in contradiction with each other with respect to the magnitude of Km. Additionally, fitting the portion of the timecourse that corresponded to the consumption of the final 2 μM of OMP gave a kcat/Km value of approximately 600 M−1 s−1. In other double mutants of ScOMPDC, the mutations behaved nearly independently in that the effects of the mutations on kcat/Km were essentially multiplicative [8]. That would predict that for Q215A/R235A OMPDC, kcat/Km should be approximately 12 M−1 s−1, 50 times smaller than the second order rate constant determined from the reaction timecourse.

Figure 5.

Timecourse of decarboxylation of 27 μM OMP catalyzed by 9.6 μM of the initial batch of mutant ScOMPDC. Dotted curve: Plot of absorbance at 279 nm as a function of time. Solid curve: A single exponential function that would have fit the data well had the enzyme been pure. The fit gives kcat/Km = 600 M−1s−1 for the decay of the last 2 μM of OMP.

Figure 6.

Kinetic measurements of OMP decay for the stringently purified mutant ScOMPDC. (A) Initial velocity measurements of OMP decarboxylation catalyzed by 4.0 μM mutant ScOMPDC. Data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation (eq. 1) to give kcat = 0.02 s−1, Km = 1500 μM, and kcat/Km = 13 M−1s−1. (B) Timecourse of decarboxylation of 150 μM OMP catalyzed by 21 μM of the second, stringently purified batch of mutant ScOMPDC. The solid curve is the single exponential function that fits the data well, giving kcat/Km = 11 M−1s−1 over the entire timecourse

This discrepancy between the reaction timecourse and initial velocity measurements could be caused by enzyme contamination as described above. This would correspond to class 3, a mixture of activity from both of the enzymes present (Fig. 3). A possible identity for the second enzyme is the wild-type form of E. coli OMPDC (EcOMPDC), which has a Km of 22 µM [5]. At relatively low [OMP] in the reaction timecourse, EcOMPDC would dominate the activity, explaining the zero-order behavior seen in the timecourse (Fig. 5). At relatively high [OMP] in the initial velocity plots, mutant ScOMPDC would dominate, explaining the lack of significant saturation at ca. 1000 µM (not shown). Table 1 summarizes the kinetic parameters for the wild-type EcOMPDC and the wild-type and mutant ScOMPDCs [5,7,8]. Application of Eq. (8) with the known kcat/Km values of 630,000 and 13 M−1 s−1 for EcOMPDC and mutant ScOMPDC, respectively, along with the observed kcat/Km of 600 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 5) yielded a contamination of 0.093 mol% EcOMPDC for this initial batch of mutant ScOMPDC. Although a tenth of a percentage level of contamination would be suitable for most commercial reagents, the inactivity of mutant ScOMPDC meant that for the complete reaction timecourse of 27 µM OMP shown in Fig. 5, more than 95% of the activity was actually due to contaminating EcOMPDC. Even for the initial velocity plot (not shown), 50–70% if the activity was due to EcOMPDC, making this batch unusable for a detailed investigation of how OMPDC catalyzes the decarboxylation reaction.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for decarboxylation of OMP catalyzed by wild-type EcOMPDC, wild-type ScOMPDC, and Q215A/R235A mutant ScOMPDCa

A new batch of mutant ScOMPDC was prepared with more stringent purification, and initial velocity of reaction studies (Figure 6A) were carried out. [OMP] ranged from 180 μM to 1800 μM and the data were fit to eq. 1 to give the kinetic parameters shown in Table 1. Figure 6b shows a representative timecourse of reaction progress of 150 μM OMP that was monitored at 279 nm. It was now cleanly fit to a first-order decay over the whole reaction (eq. 3), giving kcat/Km = 13 M−1 s−1, in agreement with predicted values. There was now fully first-order behavior at the start of this timecourse, suggesting that there was no EcOMPDC present, or at least not enough to contribute meaningfully to the overall activity (Class 1).

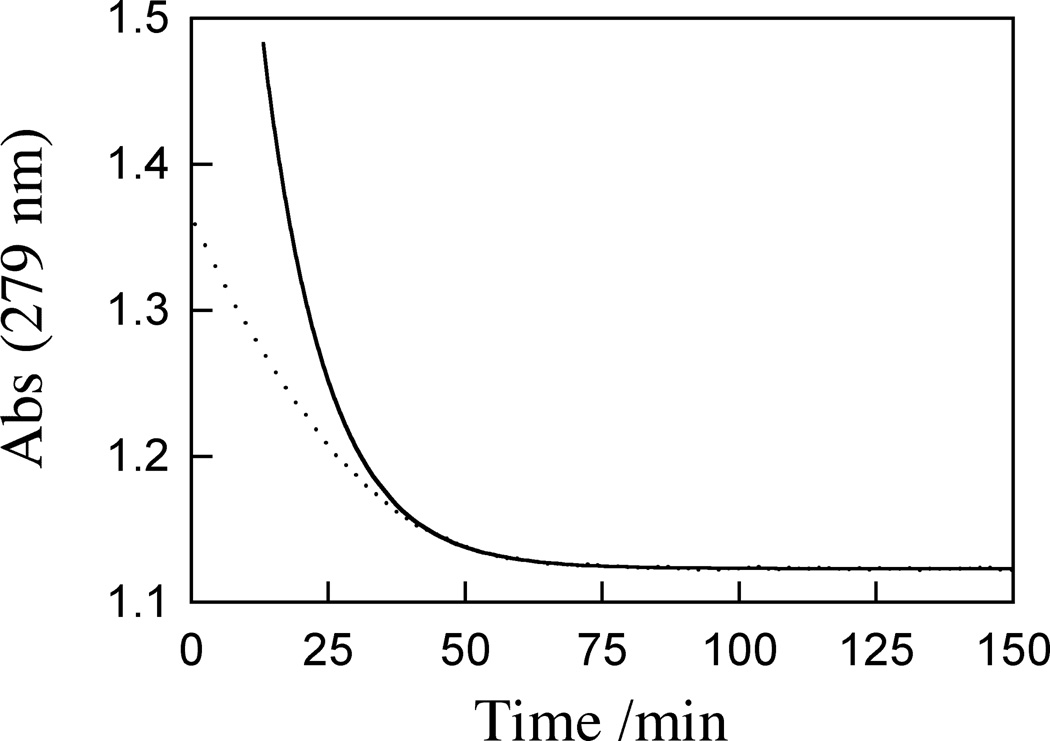

Finally, we verified that enzyme contamination was the source of the strange kinetic behavior seen in figure 5 by spiking a sample of the second, highly-purified batch of mutant ScOMPDC with 0.015 mol% of authentic EcOMPDC. At 0.015 mol% contamination, the EcOMPDC would have a minimum fractional contribution of 10% and a maximum contribution of 87%. This contribution should be detectable regardless of what [OMP] is being used in the experiment, but should not overwhelm the activity from the mutant ScOMPDC as in the original contaminated batch. Figure 7 (dotted lines) shows the reaction timecourse for the complete reaction of 120 μM OMP catalyzed by mutant ScOMPDC containing 0.015 mol% EcOMPDC. This initial substrate concentration is substantially below the Km for the mutant ScOMPDC, but substantially above Km for EcOMPDC. Fully first-order OMP decarboxylation would indicate that mutant ScOMPDC was active, while non-first-order behavior would indicate either EcOMPDC or a mixture of the two enzymes were dominant. Of particular note is that the complete reaction timecourse in figure 7 looks very much like the timecourse in figure 5, with a non-first-order beginning that later transitions into a first-order decay once the substrate concentration has been reduced to ~2 μM, significantly below the Km for EcOMPDC. The apparent (kcat/Km)obs calculated from the first-order fit of the timecourse of the decarboxylation of the final 2 μM of OMP is 75 M−1s−1 (figure 7, solid line). Eq. 8 gives an estimated EcOMPDC contamination of 0.010 mol %. This is close to the actual contamination level of 0.015% and the discrepancy may be due to the possible instability of the dimeric EcOMPDC at concentrations below 5 nM. This provides further confirmation of the efficacy of this method of determining enzyme contamination.

Figure 7.

Timecourse of decarboxylation of 120 μM OMP catalyzed by 18.4 μM of the newer batch of mutant ScOMPDC spiked with 2.7 nM EcOMPDC. Dotted curve: Plot of absorbance at 279 nm as a function of time. Solid curve: A single exponential function that would have fit the data well had the enzyme been pure. The fit gives kcat/Km = 75 M−1s−1 for the decay of the last 2 μM of OMP.

Conclusion

The fact that such small physical contamination can lead to such large kinetic effects underscores the importance of both ensuring that enzymes are well purified, and also having a reliable means to test for any enzymatic contamination. It also highlights the importance of using multiple experimental techniques such as both timecourses of complete reaction progress, and initial reaction velocity studies. While in this work the effect was due a contamination of the target mutant ScOMPDC with wild-type EcOMPDC, this could happen in practice for any pair of enzymes that catalyze the same reaction, but have very different values of their Michaelis constants, Km. These pairs of enzymes would become saturated at different substrate concentrations, resulting in each enzyme dominating the catalysis at a different range of substrate concentration. The method we utilized to determine the enzyme contamination is general and easy to apply. It only requires having a knowledge of which enzyme is contaminating the enzyme of interest, and a reliable knowledge of the kinetic parameters for both enzymes. While in the course of our experiments, the contamination was significant enough to warrant producing a more highly purified batch of the mutant ScOMPDC, should the contamination be minor, this approach would also provide a way of mathematically correcting for the activity of the wild-type enzyme without need of producing more material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. John P. Richard for helpful discussion and acknowledge the generous financial support of this work by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM039754 to J.P.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was support by Grant GM039754 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Cook PF, Cleland WW. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism. Garland Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodi PJ, Chang LC, Knowles JR, Komives EA. Triosephosphate Isomerase Requires a Positively Charged Active Site: The Role of Lysine-12. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2809–2814. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard JP, Huber RE, Lin S, Heo C, Amyes TL. Structure–Reactivity Relationships for β-Galactosidase (Escherichia coli, lac Z). 3. Evidence that Glu-461 Participates in Brønsted Acid–Base Catalysis of β-d-Galactopyranosyl Group Transfer. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12377–12386. doi: 10.1021/bi961028j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson TE, Walsh CT, Massey V. Kinetic Characterization of Wild-Type and S229A Mutant MurB: Evidence for the Role of Ser 229 as a General Acid. Biochemistry. 1997;6:796–805. doi: 10.1021/bi962220o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Dissecting the Total Transition State Stabilization Provided by Amino Acid Side Chains at Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7785–7787. doi: 10.1021/bi800939k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Activation of R235A mutant orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase by the guanidinium cation: effective molarity of the cationic side chain of Arg-235. Biochemistry. 2010;49:824–826. doi: 10.1021/bi902174q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toth K, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. An Examination of the Relationship between Active Site Loop Size and Thermodynamic Activation Parameters for Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase from Mesophilic and Thermophilic Organisms. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8006–8013. doi: 10.1021/bi901064k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amyes TL, Ming SA, Goldman LM, Wood BM, Desai BJ, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Transition State Stabilization from Remote Protein‱Phosphodianion Interactions. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4630–4632. doi: 10.1021/bi300585e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood BM, Chan KK, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Gerlt JA. Mechanism of the Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase-Catalyzed Reaction: Effect of Solvent Viscosity on Kinetic Constants. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5510–5517. doi: 10.1021/bi9006226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sievers A, Wolfenden R. The effective molarity of the substrate phosphoryl group in the transition state for yeast OMP decarboxylase. Bioorg. Chem. 2005;33:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffatt JG. The Synthesis of Orotidine-5' Phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:1118–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalano J, Sadre-Bazzaz K, Amodeo GA, Tong L, McDermott A. Structural Evidence: A Single Charged Residue Affects Substrate Binding in Cytochrome P450 BM-3. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6807–6815. doi: 10.1021/bi4000645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassila JK, Keeffe JR, Kast P, Mayo SL. Exhaustive Mutagenesis of Six Secondary Active-Site Residues in Escherichia coli Chorismate Mutase Shows the Importance of Hydrophobic Side Chains and a Helix N-Capping Position for Stability and Catalysis. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6883–6891. doi: 10.1021/bi700215x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller BG, Wolfenden R. Catalytic proficiency: the unusual case for OMP decarboxylase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:847–885. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter DJT, Short SA. Yeast orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase: steadystate and pre-steady-state analysis of the kinetic mechanism of substrate decarboxylation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11788–11800. doi: 10.1021/bi001199v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callahan BP, Miller BG. OMP decarboxylase - an enigma persists. Bioorg. Chem. 2007;35:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JK, Tantillo DJ. Orotidine monophosphate decarboxylase: A mechanistic dialogue. Top. Curr. Chem. 2004;238 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion at the Active Site of Orotidine 5‘-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: pKa of the C-6 Proton of Enzyme-Bound UMP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1574–1575. doi: 10.1021/ja710384t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toth K, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Product Deuterium Isotope Effect for Orotidine 5‘-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Evidence for the Existence of a Short-Lived Carbanion Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12946–12947. doi: 10.1021/ja076222f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goryanova B, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. OMP Decarboxylase: Phosphodianion Binding Energy Is Used To Stabilize a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6545–6548. doi: 10.1021/ja201734z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsang W-Y, Wood BM, Wong FM, Wi W, Gerlt JA, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Proton Transfer from C-6 of Uridine 5'-Monophosphate Catalyzed by Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate and the Effect of a 5-Fluoro Substituent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14580–14594. doi: 10.1021/ja3058474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller BG, Hassell AM, Wolfenden R, Milburn MV, Short SA. Anatomy of a proficient enzyme: The structure of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase in the presence and absence of a potential transition state analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030409797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]