Abstract

Background:

Although studies have shown a cross-sectional link between discrimination and smoking, the prospective influence of discrimination on smoking cessation has yet to be evaluated. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to determine the influence of everyday and major discrimination on smoking cessation among Latinos making a quit attempt. Methods: Participants were 190 Spanish speaking smokers of Mexican Heritage recruited from the Houston, TX metropolitan area who participated in the study between 2009 and 2012. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the associations of everyday and major discrimination with smoking abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit. Results: Most participants reported at least some everyday discrimination (64.4%), and at least one major discrimination event (56%) in their lifetimes. Race/ethnicity/nationality was the most commonly perceived reason for both everyday and major discrimination. Everyday discrimination was not associated with post-quit smoking status. However, experiencing a greater number of major discrimination events was associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence, OR = .51, p = .004, and continuous smoking abstinence, OR = .29, p = .018, at 26 weeks post-quit. Conclusions: Findings highlight the high frequency of exposure to discrimination among Latinos, and demonstrate the negative impact of major discrimination events on a smoking cessation attempt. Efforts are needed to attenuate the detrimental effects of major discrimination events on smoking cessation outcomes.

Keywords: Latinos, Smoking Cessation, Discrimination, Ethnicity

1. INTRODUCTION

Latino health has become a major focus of public health attention. Latinos comprise 16.3% of the total U.S. population, which represents a 43% increase since 2000, and individuals of Mexican origin represent 63% of the U.S. Latino population (Ennis et al., 2011). Discrimination is a common experience among Latinos (Lopez et al., 2010; Pérez et al., 2008), with over 60% of Latinos reporting that discrimination is a major problem (Lopez et al., 2010). For example, Hosoda et al. (2012) reported that individuals with a Mexican-Spanish accent were rated as less suitable for employment than those with an American English accent. Thus, discrimination may be particularly problematic for those who prefer to speak Spanish and/or those who are less proficient in English.

Discrimination is associated with a variety of negative health outcomes including higher rates of smoking (Lee and Ahn, 2012; Paradies, 2006) and greater nicotine dependence (Kendzor et al., in press). For example, Purnell et al. (2012) reported that the prevalence of current smoking was significantly greater among individuals who perceived racial discrimination in healthcare and/or workplace settings versus those who did not. Although studies have largely focused on the link between racial/ethnic discrimination and smoking among Black adults (Borrell et al., 2010, 2007; Corral and Landrine, 2012; Cuevas et al., 2014; Horton and Loukas, 2011; Landrine and Klonoff, 2000; Nguyen et al., 2012), research suggests that discrimination is similarly linked with smoking prevalence among Latinos (Albert et al., 2008; Lorenzo-Blanco and Cortina, 2012; Todorova et al., 2010). Although smoking prevalence is lower among Latinos than in the general U.S. population (12.5% vs. 19.3%; CDC, 2011), the leading causes of death among Latinos (i.e., cancer, cardiovascular disease) are related to smoking (Heron, 2012). Moreover, lung cancer, a primarily smoking-related disease, is the leading cause of cancer death among Latinos (USCS, 2013). Therefore, reducing tobacco use is essential to chronic disease prevention among Latinos.

Negative affect, low self-efficacy, and diminished perceptions of social status may function as key mechanisms linking discrimination with unhealthy behaviors and poor health (Chae et al., 2011; Cuevas et al., 2013; Gee et al., 2006; Lee and Ahn, 2012; Molina et al., 2013; Pascoe and Richman, 2009; Purnell et al., 2012; Torres et al., 2012). In a recent meta-analysis, Lee and Ahn reported that discrimination among Latinos was strongly associated with negative affect and unhealthy behavior, and that intrapersonal variables (e.g., self-efficacy, self-esteem) were associated with both discrimination and physical/mental health outcomes (Lee and Ahn, 2012). Molina et al. (2013) reported that discrimination was associated with poorer self-rated health through perceptions of diminished U.S. social status and negative affect. Further, numerous studies have demonstrated a link between smoking relapse and negative affect (Businelle et al., 2010; Cofta-Woerpel et al., 2011; Piasecki, 2006; Piper et al., 2011; Shiffman, 2005) and low self-efficacy (Baer et al., 1986; Gwaltney et al., 2005; Matheny and Weatherman, 1998; Shiffman, 2005). Thus, discrimination may have a negative influence on smoking cessation via increased negative affect, diminished self-efficacy, and low perceived social status.

Despite theoretical plausibility, studies have yet to evaluate the influence of discrimination experiences on smoking cessation. Previous studies of discrimination and smoking status among Latinos have focused on several conceptualizations of discrimination including everyday discrimination, lifetime racial/ethnic or language discrimination of any type, and discrimination in healthcare settings (Albert et al., 2008; Lorenzo-Blanco and Cortina, 2012; Todorova et al., 2010). Major experiences of discrimination, such as being fired from a job, could also have a significant impact on behaviors such as smoking and smoking cessation. Studies are needed to determine the prospective influence of everyday and major discrimination on smoking cessation outcomes among Latinos making a quit attempt. A focus on individuals of Mexican heritage is warranted given that this group comprises the largest proportion of a rapidly growing population and Spanish-speaking individuals may be particularly likely to experience discrimination. Thus, the primary goals of the current study were to: 1) characterize both major and everyday discrimination experiences among Spanish-speaking individuals of Mexican heritage making a smoking quit attempt, and 2) examine the influence of major and everyday discrimination experiences on smoking cessation in this population.

2. METHODS

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data were collected as part of a longitudinal study designed to examine neighborhood, individual, and acute intrapersonal and contextual determinants of smoking cessation among Spanish-speaking individuals of Mexican heritage making a quit attempt. Participants were tracked from 2 weeks prior to their quit date through 26 weeks post-quit. All participants received smoking cessation treatment including nicotine patch therapy, self-help materials, and brief in-person and telephone counseling based on an empirically validated intervention for Spanish-speaking smokers (Wetter et al., 2007). Questionnaire data utilized in the current study were collected at the baseline pre-quit visit, and smoking cessation was assessed at 26 weeks post-quit.

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited through Spanish language media advertising (radio and newspaper; n=165) in the Houston metropolitan area and through the population-based Mexican American Cohort Study (MACS; n=34). Please note that recruitment method was not associated with cessation outcomes in the current study. The MACS is an ongoing longitudinal study of risk factors for disease and mortality among individuals of Mexican heritage (see Barcenas et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2005). Individuals were eligible to participate if they: 1) were an adult of Mexican heritage, 2) preferred to speak in Spanish, 3) were between the ages of 18 and 65 years, 4) were a current smoker with a history of smoking at least 5 cigarettes/day during the past year, 5) had an expired carbon monoxide level of ≥ 8 parts per million, 6) were motivated to quit smoking within the next 30 days, and 7) possessed a valid home address and a functioning home telephone number. Individuals were excluded for the following reasons: 1) use of the nicotine patch was contraindicated, 2) active substance use disorder, 3) regular use of tobacco products other than cigarettes, 4) use of bupropion or nicotine replacement products other than the nicotine patches supplied by the study, 5) pregnancy or lactation, 6) another household member was enrolled in the study, or 7) had participated in another smoking cessation program or research study within the past 90 days. Individuals participated in the study between 2009 and 2012.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographic Information

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were measured including age, gender, partner status (married/living with partner vs. single/divorced/separated/widowed), nativity (born in the U.S vs. outside of the U.S), years living in the U.S., and educational attainment (< high school vs. ≥ high school).

2.2.2 Tobacco Use

Tobacco use characteristics included expired carbon monoxide, years of smoking, daily smoking rate, and time to first cigarette upon waking in the morning. The Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) was calculated based on daily smoking rate and time to first cigarette (Borland et al., 2010). HSI scores may range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater nicotine dependence.

2.2.3 Discrimination

The Everyday Discrimination Scale is a 10-item self-report measure of day-to-day experiences of discrimination (e.g., people act as if they are better than you; MacArthur, 2008a; Williams et al., 1997). This measure inquires about the frequency of specific discriminatory events. Items are rated on a 6-point scale: 1=never, 2=less than once a year, 3=a few times a year, 4=a few times a month, 5=at least once a week, 6=almost every day. Total scores reflect the average rating across 9 items. One additional item assessed the perceived reason for the discrimination. The reliability and validity of the measure have previously been demonstrated (Krieger et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2004). The MacArthur Major Experiences of Discrimination Questionnaire is a self-report measure of major experiences of discrimination over the lifetime (see Kessler et al., 1999; MacArthur, 2008b; Williams, 2012). The measure inquires about the number of times that each of 11 major discrimination events were experienced (e.g., not hired for a job, fired, etc.), the perceived reason for the discrimination (e.g., race/ethnicity), the extent to which discrimination has interfered with having a full and productive life, and the extent to which life has been harder because of discrimination. The lifetime number of discrimination events experienced was summed for a total score.

2.2.4 Smoking Abstinence

Seven-day point prevalence abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit was defined as a self-report of abstinence from smoking during the previous 7 days, verified by either an expired CO level of < 8 parts per million or a salivary cotinine level of < 20 ng/ml. Continuous abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit was defined as a self-reports of complete abstinence from smoking since the quit date, verified by either an expired carbon monoxide (CO) level of < 8 parts per million or a salivary cotinine level of <20 ng/ml. Participants who self-reported a lapse and/or produced carbon monoxide or cotinine levels inconsistent with abstinence were considered non-abstinent. In cases where abstinence status could not be determined due to missing data, participants were considered non-abstinent consistent with an “intent-to-treat” approach.

2.3 Statistical Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit and 1) scores on the measure of everyday discrimination, and 2) the number of major discrimination events experienced over the lifetime as measured at the baseline pre-quit visit. Age, gender, educational attainment, partner status, years living in the U.S., and HSI scores were included as covariates in each model. Interactions between each covariate and discrimination (everyday and major) were tested while controlling for all other covariates.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Of the 199 Spanish-speaking smokers of Mexican heritage recruited in the parent study, 9 were excluded from all analyses because they were missing data on both discrimination measures (n = 3) or on any of the covariates (n=6). Thus, the overall sample size was reduced to 190 participants. At 26-weeks post-quit, 15.8% (n = 30) of participants had achieved 7-day point prevalence abstinence and 7.4% (n = 14) had achieved continuous abstinence. See Table 1 for participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 190)

| % | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | - | 37.4 (9.9) | 19-63 |

| Gender (% female) | 35.8 | - | - |

| Partner Status (% married/living with a partner) | 68.9 | - | - |

| Education (% ≥ high school ) | 41.6 | - | - |

| Annual Household Income (% ≤ $30,000) | 56.8 | ||

| Insurance Status (% uninsured) | 68.4 | - | - |

| Nativity (% born outside of the US) | 89.5 | - | - |

| Years Living in the U.S. | - | 18.7 (11.7) | 0-57 |

| Cigarettes Smoked Per Day | - | 15.8 (9.5) | 3-80 |

| Years of Smoking | - | 20.1 (9.3) | 1-45 |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) | - | 2.6 (1.6) | 0-6 |

3.2 Everyday Discrimination Experiences

Thirteen participants did not complete the everyday discrimination measure, and were excluded from all related analyses, leaving a sample of 177. The average score on the everyday discrimination measure was 1.8 (SD = .9), and 64.4% of participants reported at least some everyday discrimination (i.e., score > 1). Higher scores on the everyday discrimination measure were associated with younger age, r = -.159, p = .034, greater cigarettes smoked per day (at baseline), r = .223, p = .039, fewer years of smoking, r = -.155, p = .039, and reporting a greater number of major discrimination events, r = .280, p = .001. Everyday discrimination scores did not vary by gender, partner status, or education, and were not associated with years living in the U.S. The most frequently reported everyday discrimination experiences included: people acting as if they are better than you, being treated with less courtesy than other people, and being treated with less respect than other people (see Table 2). Of those who reported some discrimination (n = 114), perceived reasons for everyday discrimination included race/ethnicity/nationality (38.5%), height/weight/other aspect of appearance (13.1%), age (5.3%), gender (1.7%), sexual orientation (1.7%), physical limitations (1.0%), religion (1.0%) and other/missing (37.7%).

Table 2.

Everyday discrimination experiences among Spanish-Speaking smokers of Mexican heritage (N = 177).

| Everyday Discrimination | > Never (%) | ≥ A Few Times a Month (%) |

Mean Item Score (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| People act as if they are better than you | 48.0 | 16.4 | 2.2 (1.6) |

| Treated with less courtesy than other people | 47.5 | 20.3 | 2.2 (1.5) |

| Treated with less respect than other people | 41.2 | 15.2 | 2.0 (1.4) |

| People act as if they think you are not smart | 34.5 | 10.7 | 1.8 (1.3) |

| Receive poorer services than other people at restaurants or stores |

32.2 | 6.2 | 1.7 (1.1) |

| People act as if they are afraid of you | 24.9 | 11.2 | 1.7 (1.3) |

| Called names or insulted | 24.3 | 6.8 | 1.6 (1.2) |

| People act as if they think you are dishonest | 20.9 | 4.5 | 1.4 (.9) |

| Threatened or harassed | 13.6 | 3.3 | 1.3 (.9) |

Note: Items on the Everyday Discrimination measure were rated on a 6 point scale: 1 = never, 2 = less than once a year, 3 = a few times a year, 4 = a few times amonth, 5 = at least once a week, 6 = almost every day.

3.3 Everyday Discrimination and Smoking Cessation

After controlling for age, gender, partner status, education, HSI, and years living in the U.S., logistic regression analyses indicated that everyday discrimination was not significantly associated with 7-day point prevalence or continuous abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit. None of the covariates significantly interacted with total scores on the everyday discrimination measure to predict smoking cessation at 26 weeks post-quit.

3.4 Major Discrimination Experiences

Thirty-one participants did not complete the major discrimination measure, and were excluded from all related analyses, leaving a sample of 159. Participants reported experiencing an average of 1.7 (SD = 2.1; range 0-10) lifetime major discrimination events, and 56% reported at least 1 major discrimination event. The number of major discrimination experiences reported did not vary by gender, nativity, partner status, or education, and was not associated with age, smoking characteristics, or years living in the US. The most commonly reported major discrimination experiences included not being hired for a job, not receiving a job promotion, and being fired from a job (see Table 3). A total of 15.8% of participants indicated that discrimination had interfered with having a full or productive life either “somewhat” or “a lot,” and 12.0% indicated that discrimination had made life “somewhat” or “a lot” harder. Of those who reported at least 1 major discrimination event (n = 89), perceived reasons for major discrimination events included race/ethnicity/nationality (60.7%), height/weight/other aspect of appearance (5.6%), age (4.5%), gender (2.3%), sexual orientation (1.1%), physical limitations (1.1%), and other/missing (24.7%).

Table 3.

Major discrimination experiences among Spanish-Speaking smokes of Mexican heritage (N = 159).

| MacArthur Major Experiences of Discrimination | ≥ 1 Event (%) | Mean Number of Events (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Not hired for a job | 32.5 | 1.5 (3.5) |

| Not given a job promotion | 25.9 | .8 (1.8) |

| Fired | 22.8 | .6 (1.5) |

| Denied a bank loan | 16.7 | .5 (1.5) |

| Hassled by the police | 14.5 | 1.1 (8.4) |

| Denied service/received inferior service by plumber, car mechanic, or other service provider |

13.2 | .6 (4.0) |

| Denied medical care/received inferior care | 12.6 | .4 (2.0) |

| Discouraged by teacher/advisor from seeking higher education |

9.0 | .2 (.9) |

| Prevented from renting/buying a home | 8.8 | .2 (.9) |

| Prevented from remaining in a neighborhood | 7.5 | .2 (1.3) |

| Denied a scholarship | 4.5 | .1 (.8) |

3.5 Major Discrimination and Smoking Cessation

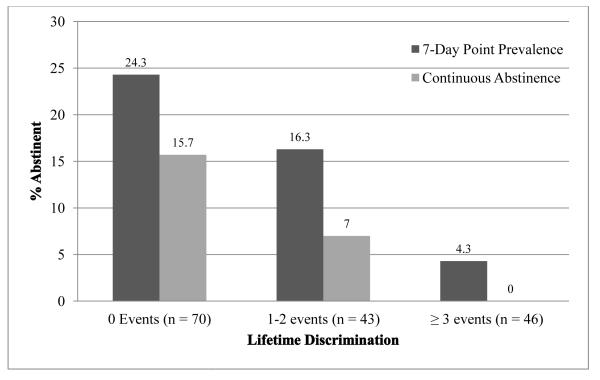

After controlling for age, gender, partner status, education, HSI, and years living in the U.S., logistic regression analyses indicated that reporting a greater number of major discrimination events was associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving both 7-day point prevalence abstinence, B = -.679, OR = .51 (95% CI, .32, .81), p = .004, and continuous abstinence, B = -1.256, OR = .29 (95% CI, .10, .80), p = .018, at 26 weeks post-quit. Abstinence rates are presented in Figure 1 by the number of discrimination events experienced. None of the covariates significantly interacted with major discrimination to predict smoking cessation at 26 weeks post-quit. Participants who achieved 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit experienced significantly fewer major discrimination events (adjusted for covariates) than those who did not (.58 vs. 1.89, p = .005). Similarly, participants who achieved continuous abstinence at 26 weeks post-quit experienced significantly fewer major discrimination events (adjusted for covariates) than those who did not (.30 vs. 1.81 events, p = .012).

Figure 1.

Abstinence rates at 26 weeks post-quit by number of major discrimination events.

4. DISCUSSION

Latinos in the current study who experienced greater lifetime exposure to major discrimination events were less likely to achieve abstinence than individuals who experienced less discrimination. In contrast, everyday discrimination was not associated with smoking cessation. More than half of participants reported that they had experienced at least one major discrimination event, with the most common events being job-related. Race/ethnicity/nationality was the most commonly perceived reason for both everyday and major discrimination experiences, though participants more frequently perceived race/ethnicity/nationality as the reason for major than everyday discrimination. Nearly two-thirds of participants reported at least some “everyday” discrimination (i.e., self-reported frequency > never). Overall, the findings demonstrate both a high frequency of exposure to discrimination among Spanish-speaking smokers of Mexican heritage, as well as the negative impact of major discrimination events on a smoking cessation attempt.

Major discrimination had a greater influence than everyday discrimination on smoking cessation outcomes. Major discrimination limits employment, education, and many other important opportunities in life, and may therefore exert a more damaging impact on perceived agency to influence outcomes in one’s life including quitting smoking. Interestingly, Perez et al. (2008) reported that Latino immigrants are less likely to perceive everyday discrimination than American-born Latinos. Nearly 90% of the current study sample was born outside of the U.S. and all participants preferred to speak Spanish. Plausibly, acculturated Latinos of Mexican descent may be more likely to perceive everyday discrimination, which could have a greater influence on cessation outcomes.

The current findings add to the large body of work aimed at understanding the social determinants of health (CSDH, 2008) and further suggests that higher level commitments (e.g., government, community, workplace) to racial/ethnic equity are needed to prevent and attenuate tobacco-related and other health disparities (see Jones, 2000). It seems particularly important to specifically address job-related discrimination (i.e., the most frequently reported type of major discrimination), perhaps through workplace policy-changes and employee education programs. At the individual level, interventions targeted at buffering the psychological impact (e.g., perceived importance) of discrimination might help to reduce the negative impact on health outcomes including smoking cessation. Previous research has indicated that discrimination may impact health though several mechanisms including increased negative affect, decreased self-efficacy, and diminished perceptions of social status (Chae et al., 2011; Cuevas et al., 2013; Gee et al., 2006; Lee and Ahn, 2012; Molina et al., 2013; Pascoe and Richman, 2009; Purnell et al., 2012; Torres et al., 2012). Additional research is needed to uncover the specific mechanisms linking discrimination and smoking cessation.

The current study has strengths and limitations. This is the first study to prospectively examine the influence of discrimination on smoking cessation outcomes. An additional strength is the specific focus on a rapidly growing and understudied Latino population that is particularly likely to experience discrimination. Weaknesses include limited generalizability outside of Spanish-speaking individuals of Mexican heritage and the relatively small sample size, which may have limited our ability to detect interactions between discrimination and other demographic and socioeconomic variables. Because participants were recruited primarily through advertising, and eligibility criteria included a willingness to make a quit attempt in the next 30 days, discrimination could potentially have an even larger effect on cessation if it serves to discourage quit attempts in addition to reducing the likelihood of successful cessation. Notably, the reasons for perceived discrimination on both measures (i.e., everyday and major) had high rates of missing or “other” responses, suggesting that there may be reasons for discrimination that were not included as response options, or that it may be difficult for individuals to identify one specific reason for discrimination experiences. Language (e.g., the limited ability to speak and/or understand English) and socioeconomic status (other than education) were not included as perceived reasons for discrimination on the measures. Conceivably, language barriers might have contributed to the high rates of job-related discrimination. Smoking might also be a reason for everyday discrimination, as scores were positively associated with cigarettes smoked per day. Future studies should attempt to identify other common reasons for perceived discrimination, so that these reasons might be recognized and addressed.

Major discrimination is associated with a reduced likelihood of cessation among Spanish-speaking individuals of Mexican heritage. More research is needed to understand the mechanisms through which major discrimination leads to smoking cessation failure. In addition, efforts are needed to address discrimination at the societal and institutional levels in order to achieve a more permanent solution to existing health disparities. Efforts to intervene at the individual-level may attenuate the detrimental effects of discrimination on health behavior until equity is achieved.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the financial support of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the American Cancer Society, the National Cancer Institute, and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (including the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment). We are grateful for the contributions of all study team members including Shanna Barnett, Erica Cantu, Gloria Cortez, Ellen Cromley, Patricia Figueroa, Araceli Flores, Jeannie Flores, Evelin McCombs, Luz Mejia, Devin Olivares-Reed, Veronica Paredes, Jewel Rawls, Maria Salazar, Eric Sanchez, and Rocio Tharp.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant P60MD000503 (to DWW). Data analysis and manuscript preparation were additionally supported through American Cancer Society grants MRSGT-10-104-01-CPHPS (to DEK) and MRSGT-12-114-01-CPPB (to MSB), National Cancer Institute grant K01CA157689 (to YC), National Cancer Institute diversity supplement grant U54CA153505 (to MAC), the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment faculty fellowship (to CEA), a National Cancer Institute CURE Diversity Supplement grant R25T CA57730 (to VCF), and National Institutes of Health Support Grant CA016672 to the MD Anderson Cancer Center. The funding sources had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributors

DEK conducted all statistical analyses and was the primary author of the manuscript. MSB, LRR, YC, JIV, CAM, PMC, CYL, CEA, VCF, and MAC contributed to study conceptualization and manuscript preparation/revision. DWW was the principle investigator on the parent project and he contributed to study conceptualization, interpretation of the statistical analyses, and manuscript preparation/revision.

REFERENCES

- Albert MA, Ravenell J, Glynn RJ, Khera A, Halevy N, de Lemos JA. Cardiovascular risk indicators and perceived race/ethnic discrimination in the Dallas Heart Study. Am. Heart J. 2008;156:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Holt CS, Lichtenstein E. Self-efficacy and smoking reexamined. Construct validity and clinical utility. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986;54:846–852. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcenas CH, Wilkinson AV, Strom SS, Cao Y, Saunders KC, Mahabir S, Hernández-Valero MA, Forman MR, Spitz MR, Bondy ML. Birthplace, years of residence in the United States, and obesity among Mexican-American adults. Obesity. 2007;15:1043–1052. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Yong HH, O'Connor RJ, Hyland A, Thompson ME. The reliability and predictive validity of the heaviness of smoking index and its two components: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 201012:S45–S50. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Shea S, Jackson SA, Shrager S, Blumenthal RS. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Prev. Med. 2010;51:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Jr, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the coronary artery risk development in adults study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;166:1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR, Costello TJ, Cofta-Woerpel L, Li Y, Mazas CA, Vidrine JI, Cinciripini PM, Greisinger AJ, Wetter DW. Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status to smoking cessation: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2010;29:262–273. doi: 10.1037/a0019285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years --- United States, 2005--2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Jackson JS. Discrimination, attribution, and racial group identification: implications for psychological distress among black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001-2003) Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2011;81:498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofta-Woerpel L, McClure JB, Li Y, Urbauer D, Cinciripini PM, Wetter DW. Early cessation success or failure among women attempting to quit smoking: trajectories and volatility of urge and negative mood during the first postcessation week. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:596–606. doi: 10.1037/a0023755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral I, Landrine H. Racial discrimination and health-promoting vs damaging behaviors among African-American adults. J. Health. Psychol. 2012;17:1176–1182. doi: 10.1177/1359105311435429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSDH . Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Reitzel LR, Adams CE, Cao Y, Nguyen N, Wetter DW, Watkins KL, Regan SD, McNeill LH. Discrimination, affect, and cancer risk factors among African Americans. Am. J. Health Behav. 2014;38:31–41. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Reitzel LR, Cao Y, Nguyen N, Wetter DW, Adams CE, Watkins KL, Regan SD, McNeill LH. Mediators of discrimination and self-rated health among African Americans. Am. J. Health Behav. 2013;37:745–754. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.6.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. 2010 Census Briefs. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2011. The Hispanic Population: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, Holt J. Self reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: the added dimension of immigration. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005;114:661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton KD, Loukas A. Discrimination, religious coping, and tobacco use among White, African American, and Mexican American vocational school students. J. Relig. Health. 2011:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9462-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda M, Nguyen LT, Stone-Romero EF. The effect of Hispanic accents on employment decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2012;27:347–364. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Reitzel LR, Rios DM, Scheuermann TS, Pulvers K, Ahluwalia JS. Everyday discrimination is associated with nicotine dependence in African American, Latino, and White Smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt198. in press. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Racial discrimination and cigarette smoking among Blacks: findings from two studies. Ethn. Dis. 2000;10:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Ahn S. Discrimination against Latina/os: a meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes ψ. Counseling Psychologist. 2012;40:28–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Morin R, Taylor P. Illegal Immigration Backlash Worries, Divides Latinos. Pew Hispanic Center; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, Cortina LM. Latino/a depression and smoking: an analysis through the lenses of culture, gender, and ethnicity. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012;51:332–346. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur Detroit Area Study Assessment of Everyday Discrimination. 2008a http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/detroit.php accessed on December 17, 2012.

- MacArthur MacArthur Midlife Survey: Major Experiences of Discrimination. 2008b http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/midmac.php accessed on November 29, 2012.

- Matheny KB, Weatherman KE. Predictors of smoking cessation and maintenance. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998;54:223–235. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199802)54:2<223::aid-jclp12>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina K, Alegría M, Mahalingam R. A multiple-group path analysis of the role of everyday discrimination on self-rated physical health among Latina/os in the USA. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013;45:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KH, Subramanian SV, Sorensen G, Tsang K, Wright RJ. Influence of experiences of racial discrimination and ethnic identity on prenatal smoking among urban black and Hispanic women. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2012;66:315–321. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.107516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J. Community Psychol. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM. Relapse to smoking. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:196–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Schlam TR, Cook JW, Sheffer MA, Smith SS, Loh WY, Bolt DM, Kim SY, Kaye JT, Hefner KR, Baker TB. Tobacco withdrawal components and their relations with cessation success. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:569–578. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2250-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell JQ, Peppone LJ, Alcaraz K, McQueen A, Guido JJ, Carroll JK, Shacham E, Morrow GR. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress, and current smoking status: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system reactions to race module, 2004-2008. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102:844–851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. J. Pers. 2005;73:1715–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TR, Kamarck TW, Shiffman S. Validation of the Detroit Area Study Discrimination Scale in a community sample of older African American adults: the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2004;11:88–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, Price LL. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociol. Health Illn. 2010;32:843–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Driscoll MW, Voell M. Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: a moderated mediational model. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2012;18:17–25. doi: 10.1037/a0026710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USCS 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. 2013 www.cdc.gov/uscs.accessed on March 4, 2013.

- Wetter DW, Mazas C, Daza P, Nguyen L, Fouladi RT, Li Y, Cofta-Woerpel L. Reaching and treating Spanish-speaking smokers through the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Information Service: a randomised controlled trial. Cancer. 2007;109:406–413. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AV, Spitz MR, Strom SS, Prokhorov AV, Barcenas CH, Cao Y, Saunders KC, Bondy ML. Effects of nativity, age at migration, and acculturation on smoking among adult Houston residents of Mexican descent. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95:1043–1049. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Measuring Discrimination Resource. 2012 http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/davidrwilliams/files/measuring_discrimination_resource_feb_201 2_0.pdf accessed on November 29, 2013.

- Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health. J. Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]