Abstract

Importance

There have been recent calls for increased access to mental health services, but access may be limited due to psychiatrist refusal to accept insurance.

Objective

To describe recent trends in acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists compared with physicians of other specialties.

Design

We used data from a national survey of office-based physicians to calculate rates of acceptance of private fee-for-service insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid by psychiatrists versus physicians of other specialties and to compare the characteristics of psychiatrists who accepted insurance with those who did not.

Participants

Office-based physicians in the U.S.

Main Outcome Measure

Our main outcome variables were physician acceptance of new patients with private fee-for-service insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid. Our main independent variables were physician specialty and year groupings (2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010).

Results

The percentage of psychiatrists who accepted private fee-for-service insurance was significantly lower than physicians of other specialties in 2009–2010 (55.3% [95% CI, 46.6, 63.8] versus 88.7% [95% CI 86.4, 90.7], p<0.001) and declined by 17.0% since 2005–2006. Similarly, the percentage of psychiatrists who accepted Medicare in 2009–2010 was significantly lower than physicians of other specialties (54.8% [95% CI 46.6, 62.7] versus 86.1% [95% CI 84.4, 87.7], p<0.001) and declined by 19.5% since 2005–2006. Psychiatrists’ Medicaid acceptance rates were lower than physicians of other specialties in 2009–2010 (43.1% [95% CI, 43.1, 51.7] versus 73.0% [95% CI 70.3, 75.5], p<0.001) but did not decline significantly from 2005–2006. Psychiatrists in the Midwest were more likely to accept private fee-for-service insurance (85.1%) than psychiatrists in the Northeast (48.5%), South (43.0%), and West (57.8%, p=0.02).

Conclusions and Relevance

Acceptance rates of all types of insurance were significantly lower for psychiatrists than for physicians of other specialties. These low rates of acceptance may pose a barrier to access to mental health services.

Background

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that a quarter of adults in the United States report having a mental illness at any given time and about half of adults will suffer from a mental illness during their lifetime.1 In the wake of the Connecticut school shooting and other recent mass shootings, policymakers and the public have called for increased access to mental health services.2 For example, the President’s “Now is the Time” proposal, which was released in January 2013, called for better mental health services, including programs to identify diagnosable mental health problems early so that patients can be referred for treatment and increased training of mental health professionals.2

Psychiatrists play an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with mental illnesses particularly because of their training and ability to prescribe medications.3 One issue that advocates for increased mental health access have neglected to explore is limited access due to psychiatrists’ refusal to accept insurance.4 In previous studies, we and others have shown that overall physician acceptance rates for private fee-for-service insurance was high but declining modestly in recent years.5–7 Little is known, about specialty differences in insurance acceptance rates, but prior reports suggest that non-acceptance of insurance may be particularly high for psychiatrists.8,9 Non-acceptance of insurance may have implications on access to care for patients with mental illness and may limit the ability of policymakers to implement proposals to improve access for patients. Understanding the characteristics and predictors of psychiatrists who do not accept insurance may also help the medical community understand where and why this might be a particular problem.

To assess this potential problem, we used a national survey of office-based physicians to answer two research questions: 1) what are recent trends in acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists compared with physicians of other specialties, and 2) what are the characteristics of psychiatrists who do not accept insurance?

Methods

Data Source

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is a nationally representative survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). It contains information about physicians practicing in non-federally-funded, non-hospital-based offices throughout the United States.10,11 Physicians in the fields of anesthesiology, radiology, and pathology are excluded. Approximately 90% of outpatient visits in the U.S. are seen by the office-based physicians represented in the NAMCS.

The NAMCS uses a multistage sampling design based on geographic primary sampling units and physicians practicing within those units. Physicians are identified from the American Medical Association’s and the American Osteopathic Association’s master files. Each physician-responder is then weighted based on the sampling design so the data can be used for national estimates.12

The NAMCS collects information on physician and practice characteristics in an induction survey. For this study, we used data from the 2005 to 2010 induction surveys.

Study Sample

We restricted our sample to physicians who reported that they accepted new patients (95.3% of surveyed physicians across all study years). For our analysis of physician acceptance of Medicare, we excluded pediatricians because they rarely care for Medicare patients. We included pediatricians in all other analyses.

Variables

Our main outcome variables were physician acceptance of new patients with private fee-for-service insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid. Our main independent variables were physician specialty and two year groupings (2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010). In our comparison of psychiatrists who accept private fee-for-service insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid versus with those who do not, we looked at practice region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and practice size (solo, group).

Analysis

We report percentages of physicians who accepted new patients by insurance type and by two year grouping. All percentages are weighted at the physician level to reflect the sampling design of the NAMCS so that national estimates can be reliably calculated. We used regression models to estimate linear trends over time in physician acceptance of new patients by insurance type and by physician specialty (psychiatrists vs. all other specialties).13 For 2009 and 2010, we report the percentages of physicians who accepted new patients with each of the three types of insurance (private fee-for-service, Medicare, and Medicaid) for 15 specialties. We used the Pearson Chi-squared test to compare acceptance rates for psychiatrists with acceptance rates for physicians of all other specialties in 2009 and 2010 and to compare characteristics of psychiatrists who accept each insurance type compared with those who do not accept each insurance type. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

The Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

The mean number of physicians surveyed from each year between 2005 and 2010 was 1250 (range 1058 to 1357), representing approximately 300,000 office-based physicians. Psychiatrists were 5.5% of these physicians.

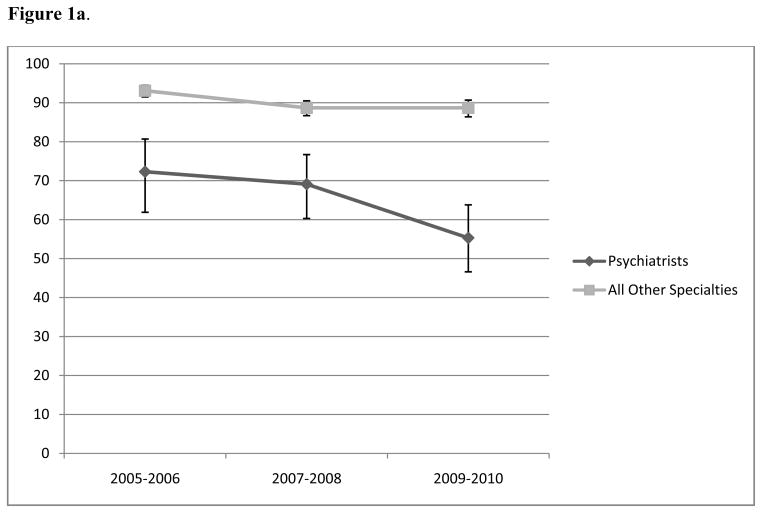

The percentage of psychiatrists who accepted private fee-for-service insurance was lower than other physicians in all years and decreased by 17.0%, from 72.3% in 2005–2006 (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 61.9, 80.7) to 55.3% in 2009–2010 (95% CI, 46.6, 63.8; p=0.01 for trend across years, Figure 1a). The percentage of physicians of other specialties who accepted private fee-for-service insurance decreased by 4.4%, from 93.1% in 2005–2006 (95% CI 91.5, 94.5) to 88.7% in 2009–2010 (95% CI 86.4, 90.7; p<0.001 for trend across years).

Figure 1.

shows the percentage of office-based psychiatrists who accept various forms of insurance between the years 2005-2010.

Figure 1a. Percentage of office-based physicians who accepted private non-capitated insurance, 2005–2010a,b,c

a survey-weighted percentages based on the sample that was surveyed

b sample includes only physicians who accepted new patients in each study year

c p=0.01 for trend across years for psychiatrists, p<0.001 for trend across years for all other specialties

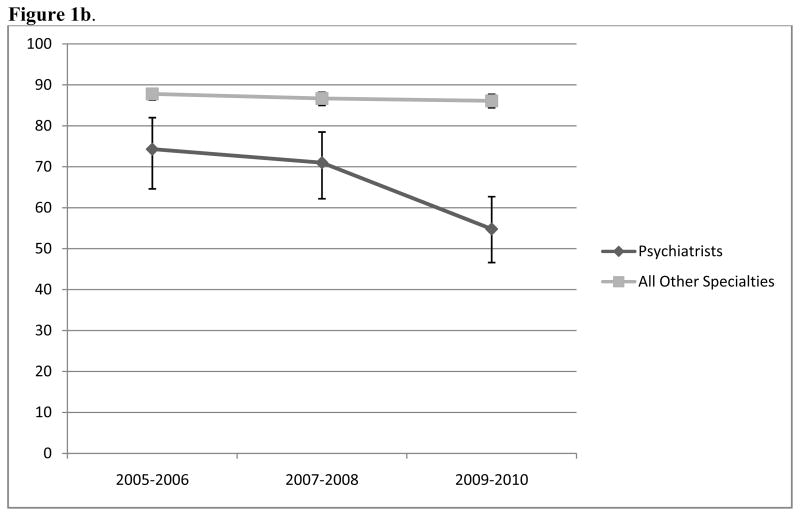

Figure 1b. Percentage of office-based psychiatrists who accepted Medicare, 2005–2010a,b,c

a survey-weighted percentages based on the sample that was surveyed

b sample includes only physicians who accepted new patients in each study year and exclude pediatricians

c p<0.001 for trend across years for psychiatrists, p=0.14 for trend across years for all other specialties

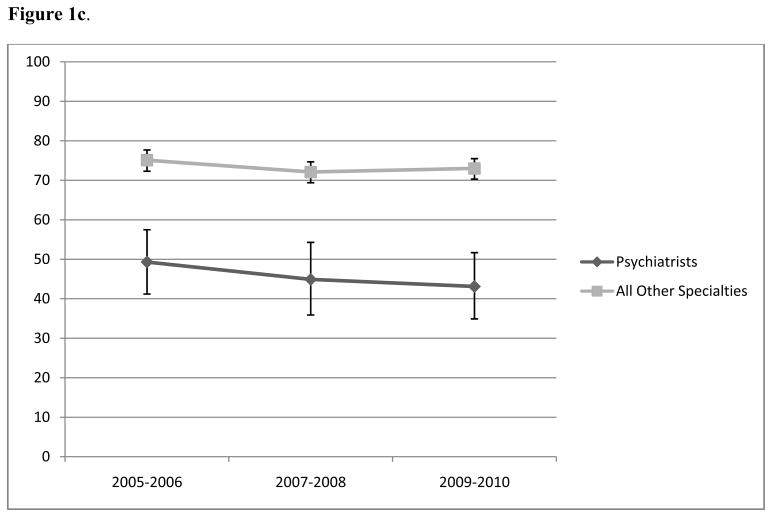

Figure 1c. Percentage of office-based psychiatrists who accepted Medicaid, 2005–2010 a,b,c

a survey-weighted percentages based on the sample that was surveyed

b sample includes only physicians who accepted new patients in each study year

c p=0.29 for trend across years for psychiatrists, p=0.25 for trend across years for all other specialties

The percentage of psychiatrists who accepted Medicare was lower than other physicians in all years and decreased by 19.5%, from 74.3% in 2005–2006 (95% CI 64.6, 82.0) to 54.8% in 2009–2010 (95% CI 46.6, 62.7, p<0.001 for trend across years, Figure 1b). The percentage of physicians of other specialties (excluding pediatrics) who accepted Medicare was unchanged (87.8% in 2005–2006 [95% CI 86.3, 84.4] and 86.1% in 2009–2010 [95% CI 84.4, 87.7]; p=0.14 for trend across years).

Psychiatrists’ Medicaid acceptance rates were lower than other physicians across all years (Figure 1c) but these rates did not decline significantly from 2005–2006 to 2009–2010 for psychiatrists (49.3% in 2005–2006 [95% CI 41.2, 57.5] and 43.1% in 2009–2010 [95% CI, 43.1, 51.7]; p=0.29) or for physicians of other specialties (75.1% in 2005 [95% CI 75.1, 77.7] to 73.0% in 2010 [95% CI 70.3, 75.5]; p=0.21).

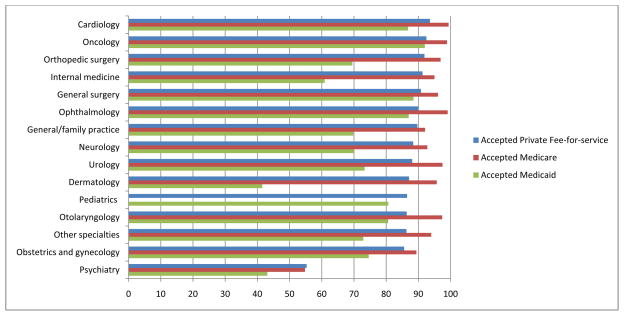

In 2009–2010, 55.3% (95% CI 46.7, 63.7) of psychiatrists accepted private fee-for-service insurance versus 88.7% (95% CI 86.4, 90.7), on average, of physicians of all other specialties (mean acceptance for all other specialties=88.7%, 95% CI [86.4, 90.7], p<0.01; Figure 2). The specialties with the highest rates of acceptance of private fee-for-service insurance were cardiology (93.6%, 95% CI 88.3, 96.6), oncology (92.5%, 95% CI 71.4, 98.4), and orthopedic surgery (91.9%, 95% CI 85.3, 95.3).

Figure 2.

shows the percentage of office-based physicians who accept insurance by specialty type in 2009-2010.

Percentage of office-based physicians who accepted insurance by specialty, 2009–2010a,b,c

a survey-weighted percentages based on the sample that was surveyed

b sample includes only physicians who accepted new patients in each study year. Medicare sample excludes pediatricians.

c p<0.001 for comparison of psychiatrists and other specialties for all insurance types

For that same time period, 54.8% (95% CI 46.6, 62.7) of psychiatrists accepted Medicare compared with a mean of 86.1% (95% CI 84.4, 87.7) of physicians of other specialties. The specialties with the highest rates of Medicare acceptance were cardiology (99.4%, 95% CI 95.6, 99.9), ophthalmology (99.1%, 95% CI 93.8, 99.9), and oncology (98.9%, 95% CI 92.2, 99.9).

Psychiatrists had a low rate of Medicaid acceptance (43.1%, 95% CI 34.9, 51.7). The specialties with the highest rates of Medicaid acceptance were general surgery (88.5%, 95% CI 79.1, 93.9), cardiology (86.8%, 95% CI 80.0, 91.5), and pediatrics (80.7%, 95% CI 74.3, 85.7). Psychiatrists in the Midwest were more likely to accept private fee-for-service insurance (85.1%, 95% CI 59.5, 95.7 than psychiatrists in the Northeast (48.5%, 95% CI 33.8, 63.4), South (43.0%, 95% CI 29.1, 58.1), and West (57.8%, 95% CI 38.3, 75.1, p=0.02, Table). This regional difference was not seen for Medicare or Medicaid acceptance. Among psychiatrists, 51.5% [95% CI 42.9, 60.0] accepted Medicare, and [39.0%, 95% CI 30.8, 47.9] accepted Medicaid). Psychiatrists in solo practice were less likely to accept all types of insurance (43.0% [95% CI 32.7,54.0] of solo practitioners accepted private-fee-for service vs. 74.9% [95% CI 58.5, 86.4] of those in groups, p=0.002; 45.0% [95% CI [34.3, 56.3] of solo practitioners accepted Medicare vs. 69.5% [95% CI 55.6, 80.6] of those in groups, p=0.01; 26.8% [95% CI 18.1, 37.9] of solo practitioners accepted Medicaid vs. 67.3% [95% CI 53.3, 78.8] of those in groups, p<0.001).

Table.

Differences in characteristics between psychiatrists who did not accept insurance and those who did, 2009–2010a,b,c

| All, % | Accepted new private-fee-for service patients | Accepted new Medicare patients | Accepted new Medicaid patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-value | No | Yes, % | p-value | No, % | Yes, % | p-value | ||

| Region | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.31 | |||||||

| Northeast, % | 28.1 | 55.6 | 48.5 | 43.5 | 56.6 | 57.7 | 42.3 | |||

| Midwest, % | 16.1 | 14.9 | 85.1 | 26.3 | 73.7 | 47.8 | 52.2 | |||

| South, % | 28.7 | 57.0 | 43.0 | 44.9 | 55.1 | 49.8 | 50.2 | |||

| West, % | 27.0 | 42.2 | 57.8 | 59.1 | 40.9 | 68.5 | 31.5 | |||

| Solo practice | 0.002 | 0.01 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Yes, % | 60.1 | 57.0 | 43.0 | 55.0 | 45.0 | 73.2 | 26.8 | |||

| No, % | 39.9 | 25.1 | 74.9 | 30.5 | 69.5 | 32.7 | 67.3 | |||

survey-weighted percentages based on the sample that was surveyed

sample includes only psychiatrists who accepted new patients in each study year

percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding

Conclusions

In this analysis of a national survey of office-based physicians, acceptance rates of all types of insurance were significantly lower for psychiatrists than for physicians of other specialties. For private fee-for-service insurance and for Medicare, acceptance rates by psychiatrists have dropped since 2005. In 2009–2010, almost half of all psychiatrists did not accept private fee-for-service insurance and over half did not accept Medicare or Medicaid. To our knowledge, no prior studies have documented such a striking difference in insurance acceptance rates by psychiatrists and physicians of other specialties. These low rates of acceptance may impact recent calls for increased access to mental health services such the President’s “Now is the Time” proposal in the wake of the recent school shooting.

Low reimbursement has been cited as a reason why physicians do not accept insurance.6,14 While reimbursement rates for office-based psychiatric treatment are similar to those for office-based medical evaluation and management, the desire to provide psychotherapy may be a reason why many psychiatrists do not accept insurance. Average Medicare reimbursement for psychotherapy ranges from $77.05 for up to 25–30 minutes to $161.84 for 75–80 minutes.15 A report in the lay press cites these rates as a reason why psychiatrists are shifting from psychotherapy to providing only medication management.16 As a result, psychiatrists who want to provide psychotherapy may opt not to accept insurance.

A shortage of psychiatrists may also be a potential reason why many do not accept insurance. Faukler et. al. recently reported a 14% decline in the number of graduates from psychiatry training programs over an eight year period from 2000 to 2008.17 These declines coupled with an aging workforce (55% of psychiatrists are age 55 or older) may mean that the supply of psychiatrists cannot meet the demand for their care.18 As a result, many psychiatrists may have so much demand for their services that they do not need to accept insurance. Our data also suggest that psychiatrists in urban settings (where most are distributed) may have greater ability to opt out of insurance plans. Future research might investigate the extent to which non-acceptance of insurance is linked to practice locations in higher income areas.

Our data show that the majority of office-based psychiatrists practice in solo practices which can likely function with much less infrastructure than larger single-specialty or multi-specialty group practices.4 As a result, they may have little incentive to hire staff to interact with insurance companies. In addition, individuals seeing psychiatrists may have concerns about stigma associated with having a mental disorder and worry about the privacy of reports to insurance companies.

Unfortunately, the NAMCS does not ask physicians why they do not accept insurance so all of these potential explanations for our findings are hypothetical. Another limitation of our analysis is that the NAMCS does not collect specialty information or insurance acceptance information on physicians practicing in hospital outpatient departments. Nevertheless, the physicians surveyed in the NAMCS represent the physicians that see approximately 90% of outpatient visits in the U.S. Finally, the NAMCS surveys specialty based on the proportion of physicians practicing in that specialty. Although the sample of physicians is weighted to reflect these proportions, the sample of psychiatrists in the NAMCS is relatively small compared with other specialties (e.g. family practice, internal medicine). As a result, the confidence intervals of each point estimate are relatively wide.

It is unknown if low acceptance rates of insurance by psychiatrists impact access to timely care for patients with mental health problems. More research is needed to understand the barriers that patients face when trying to seek psychiatric care and the barriers that physicians face when trying to refer their patients for psychiatric care. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that policies to improve access to timely psychiatric care may be limited because many psychiatrists do not accept insurance. If, in fact, future work shows that psychiatrists do not take insurance because of low reimbursement, unbalanced supply and demand, and/or administrative hurdles, policymakers, payers, and the medical community should explore ways to overcome these obstacles.

One area that may offer lessons for improving access to psychiatry is the policy, payment, and medical community’s response to the primary care shortage. Facing this looming shortage, Medicare and Medicaid have increased payment for primary care, and new models of delivery and payment--such as the patient-centered medical home--shift care to non-physician providers and staff.19–21 Similar changes in psychiatry may incentivize more psychiatrists to accept insurance, allow them to care for more patients, and encourage more students to pursue careers in psychiatry.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bishop is supported by a National Institute On Aging Career Development Award (K23AG043499). Dr. Bishop and Dr. Press are supported in part by funds provided as Nanette Laitman Clinical Scholars in Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. Dr. Keyhani is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award. Dr. Pincus acknowledges the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Columbia University (UL1 RR024156) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for their support.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental Illness Surveillance Among Adults in the United States. Supplements. 2011 Sep 2;60(03):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Now is the time. [Accessed January 29, 2013];The President’s plan to protect our children and our communities by reducing gun violence. 2013 Jan 16; Available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/wh_now_is_the_time_full.pdf.

- 3.Hutschemaekers G, Tiemens B, Kaasenbrood A. Roles of psychiatrists and other professionals in mental healthcare: results of a formal group judgement method among mental health professionals. Br J Psychiatry. 2005 Aug;187:173–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality fo Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Declines in physician acceptance of medicare and private coverage. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jun 27;171(12):1117–1119. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham PJSA, Ginsburg PB. Physician Acceptance of New Medicare Patients Stabilizes in 2004–05. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; Jan, 2006. Tracking Report No. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. QuickStats: percentage of office-based physicians accepting new patients, by type of payment accepted—United States, 1999–2000 and 2008–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(27):928. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd JW, Linsenmeyer A, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Nardin R. The crisis in mental health care: a preliminary study of access to psychiatric care in Boston. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Aug;58(2):218–219. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 May-Jun;28(3):w490–501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 30-Day Death and Readmission Measures. Hospital Readmissions Measures [webpage] 2012 http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Data/RCD/30-day-measures.aspx.

- 11.Hayward RA, Bernard AM, Rosevear JS, Anderson JE, McMahon LF., Jr An evaluation of generic screens for poor quality of hospital care on a general medicine service. Med Care. 1993 May;31(5):394–402. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State cigarette minimum price laws - United States, 2009. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2010 Apr 9;59(13):389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peleg R, Avdalimov A, Freud T. Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to Patients: the physician’s perspective. BMC research notes. 2011;4:76. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appelbaum PS. The ‘quiet’ crisis in mental health services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):110–116. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 29, 2013.];Physician Fee Schedule Search. Available at http://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-results.aspx?Y=3&T=0&HT=1&CT=0&H1=90801&H2=99205&H3=G0121&H4=90804&H5=90805&M=1.

- 16.Harris G. Talk Doesn’t Pay, So Psychiatry Turns Instead to Drug Therapy. The New York Times. 2011 Mar 5; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faulkner LR, Juul D, Andrade NN, et al. Recent trends in american board of psychiatry and neurology psychiatric subspecialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2011 Jan-Feb;35(1):35–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Insel T. [Accessed January 29, 2012.];Psychiatry: Where are we going? 2011 Jun 3; Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2011/psychiatry-where-are-we-going.shtml.

- 19.Bodenheimer T. The future of primary care: transforming practice. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 13;359(20):2086, 2089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0805631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TH, Bodenheimer T, Goroll AH, Starfield B, Treadway K. Perspective roundtable: redesigning primary care. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 13;359(20):e24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0809050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 25;360(26):2693–2696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]