Abstract

176 ERF genes from Populus were identified by bioinformatics analysis, 13 of these in di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra were investigate by real-time RT-PCR, the results demonstrated that 13 ERF genes were highly responsive to salt stress, drought stress and ABA treatment, and all were expressed in root, stem, and leaf tissues, whereas their expression levels were markedly different in the various tissues. In roots, PthERF99, 110, 119, and 168 were primarily downregulated under drought and ABA treatment but were specifically upregulated under high salt condition. Interestingly, in poplar stems, all ERF genes showed the similar trends in expression in response to NaCl stress, drought stress, and ABA treatment, indicating that they may not play either specific or unique roles in stems in abiotic stress responses. In poplar leaves, PthERF168 was highly induced by ABA treatment, but was suppressed by high salinity and drought stresses, implying that PthERF168 participated in the ABA signaling pathway. The results of this study indicated that ERF genes could play essential but distinct roles in various plant tissues in response to different environment cues and hormonal treatment.

1. Introduction

AP2/ERFs (ethylene response factor) are plants-specific transcription factor family that was firstly identified from tobacco as the binding proteins for reduced sensitivity to disease. AP2/ERFs can be divided into multiple subtribes that include but are not limited to AP2, RAV, ERF, and DREB, according to the difference of their conserved protein domains [1]. In recent years, researches on AP2/ERF transcription factors in various species have shown that AP2/ERFs play an important role in regulating ethylene and drought responsive genes [2–7]. AP2/ERFs contain at least one AP2 conservative domain, which is made up of about 60 highly conserved amino acids [8]. AP2 domain can directly interact with DRE/CRT cis-acting element or GCC-box cis-acting element, and these elements often present the promoter regions of many stress response and tolerance genes [2, 9]. Through regulating the expression of many target genes, ERF family becomes the central part in plant signal transduction network. Most of the members of the ERF family proteins are directly induced. The hormones and environmental cues that can induce ERFs expression include but are not limited to ethylene, jasmine, ABA, salicylic acid, drought, salinity, and cold [10–13]. Interestingly, the same ERF transcription factor can be induced by multiple stress and serves as the converged point of stress-responsive signal transduction pathways in plant body [14, 15]. All these implicate that ERF transcription factors play a key role in plant stress responsive. Further understanding of how and where each ERF functions demands detailed knowledge of spatial-temporal gene expression patterns in response to various abiotic stresses. However, little is known about the tissue-specific and temporal expression patterns of ERFs in response to different abiotic stresses.

In recent years, along with the environment deterioration, high salinity, drought, and low temperature have become the major abiotic factors. However, due to the complexity of interactions and regulation in plants that are subjected to the abiotic stresses, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of stress tolerance in plants is still very limited. Knowledge of how plants perceive environment cues and then perform signal transduction that lead to augmented stress tolerance is essential for improving plants stress tolerance. Although poplars grow fast in various environments and have been used for timberland, protection forest, and afforestation, poplar growing on marginal lands is subjected to constant abiotic stresses, leading to serious losses in biomass production. Some of the major abiotic stresses are salt and drought stresses. Since its genome was sequenced in 2004 [16], poplar have been widely utilized as a woody model plant species to study the molecular mechanisms and response to the adversity stress. In this study, we detected 176 ERF genes in di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra and identified 13 ERF genes that were highly responsive to various abiotic stresses and ABA treatment. Then, we studied the spatial-temporal expression patterns of ERF family using real-time reverse-transcriptase- (RT-) PCR. This study provides further insights into the roles of ERF genes in response to abiotic stress in plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Culture and Stress Treatments

Twigs of the plant materials from the same clone of di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra were harvested. For the reproduction of new brunch and root, the twigs were planted in pots containing water and kept under controlled greenhouse conditions of 60–70% relative humidity, 14 h light/10 h dark, and an average temperature of 25°C. Two-month-old seedlings were then subjected to the following treatments: water (normal growth condition without stress: control), 0.15 M NaCl, 25 mM PEG (polyethylene glycol)-6000, or 50 μM ABA for 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 36 h. Young root, secondary stem, and leaf tissues were harvested from six seedlings at every time point during each treatments. The harvested tissue samples from each seedling were pooled, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C for RNA isolation and real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR analysis.

2.2. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA of each sample was extracted using Column Plant RNAout Kit (TIANDZ Corp., Beijing, China) according to the manufacture's instructions. Quality and quantity of RNA were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington DE, USA), respectively. Approximately one microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA in a 20 μL volume using 1 μL of RT Primer Mix as primers, and the procedures of cDNA synthesis were following the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa Corp., Dalian, China). The synthesized cDNA was diluted to 100 μL with sterile water and used as the template for RT-PCR.

Real-time RT-PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). ACT, EF1, and UBQ genes were selected as internal controls to normalize the level of total RNA present in each reaction [17]. The primer sequences for real-time RT-PCR are shown in Table 1. The RT-PCR reactions of 20 μL total volume contained 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa), 0.4 μL of ROX Reference Dye II (TaKaRa), 0.4 μM each of forward and reverse primers, and 2 μL of cDNA template (equivalent to 100 ng of total RNA). RT-PCR procedure and conditions are as follows: 10 min 95°C initial denaturation; 40 × 15 sec 95°C denaturation; 60 sec 60°C primer annealing/elongation. The fluorescence was recorded during the annealing/elongation step in each cycle. A melting curve analysis was performed at the end of each PCR by gradually increasing the temperature from 60 to 95°C while recording the fluorescence. A single peak at melting temperature of the PCR-product confirmed primer specificity. RT-PCR was carried out with three technical repeats for each of three biological repasts per clone/treatment to ensure the reproducibility of the results. Expression levels were calculated from the threshold cycle according to the delta-delta C T method [17]. Relative gene expression level was calculated as the transcription level under stress conditions divided by the transcription level under normal conditions (i.e., samples from plants grown under normal condition and harvested at the same time). Relative gene expression levels were log2 transformed.

Table 1.

Primers used in real time RT-PCR.

| Genes | GenBank number | Forward and reverse primers (5′-3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PthERF22 | XM_002297841 | ACGTGACCCTAAAAAGGCAGCTC | GTGTCTGGTGCAAATGATGAGGG |

| PthERF36 | XM_002302128 | GGCACATTTGATACTGCAGAGGC | GTTGCCTTGGAGATGAGATTGGC |

| PthERF54 | XM_002328584 | CAAGCTACACCATCCAAGTCCAG | GCTTCATCATATGCTTTGGCGGC |

| PthERF75 | XM_002318140 | TTATGGCTCCTCTAGCTCGTTCC | CTGCTGTTGAGAAGATATCGGCC |

| PthERF77 | XM_002306676 | GTCATCTGGTGCAACTGCAACTG | CCAGACTCTTGCTGCTTTGTGTG |

| PthERF80 | XM_002304604 | GTTCAAAGGCACCAAGGCTAAGC | TCTGGTGCAAATGATGAAGGGGG |

| PthERF99 | XM_002332658 | AAGTTTGCAGCAGAGATCCGTG | GATCTTCTTCTCTTCCTGCCTG |

| PthERF110 | XM_002304556 | GCTGGATTGAATGAAGCTGCTG | GCATTCTATAAGCCGCCCTATC |

| PthERF118 | XM_002315454 | GGCACTTACAACACAGCTGATG | TCAAAACTAGCCATAGCAGCCG |

| PthERF119 | XM_002325598 | AAAAACTTCAGGGGTGTCCGTC | TAGTAGGAAAGTTGGTGACGGC |

| PthERF124 | XM_002324777 | GGCGACGTTTCATTTTCCAACG | CCCACTAAAAATCCCCTCCAAG |

| PthERF154 | XM_002326261 | GAGGAAGCAGCAAGAGCATATG | GATTCCACAATCCTCTCTGCAG |

| PthERF168 | XM_002299371 | TAGCACCCAAGAAACCTGTAGC | GTACCTAACCAAACCCGACTAC |

| ACT | JM986590 | ACCCTCCAATCCAGACACTG | TTGCTGACCGTATGAGCAAG |

| EF1 | FN356200 | AAGCCATGGGATGATGAGAC | ACTGGAGCCAATTTTGATGC |

| UBQ | FJ438462 | CGTGGAGGAATGCAGATTTT | GATCTTGGCCTTCACGTTGT |

2.3. Screening of ERF Family Genes from Di-Haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra

176 Populus trichocarpa ERF transcription factors were identified through bioinformatics analysis from the PlantTFDB database [18]. Using RT-PCR analysis, total of 59 genes responding to salt stress were initially screened in leaf tissues of di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra, which were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 24 h. These genes were analyzed by BLASTX against NR and Swiss-Prot databases [19] to search for similarities. The cut-off value for BLASTX was set to E value of 10−5, and thus ERF genes with E value ≤ 10−5 were kept for further analysis.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of ERFs Sequences

The ERF genes open reading frames were resolved by the ORF Finder provided by NCBI [20]. Genes with complete ORFs were subjected to further analysis. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalX Version 2.0 [21]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA version 5.0 and the neighbor-joining (NJ) method [22].

3. Results

3.1. Identification of ERF Genes from Di-Haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra

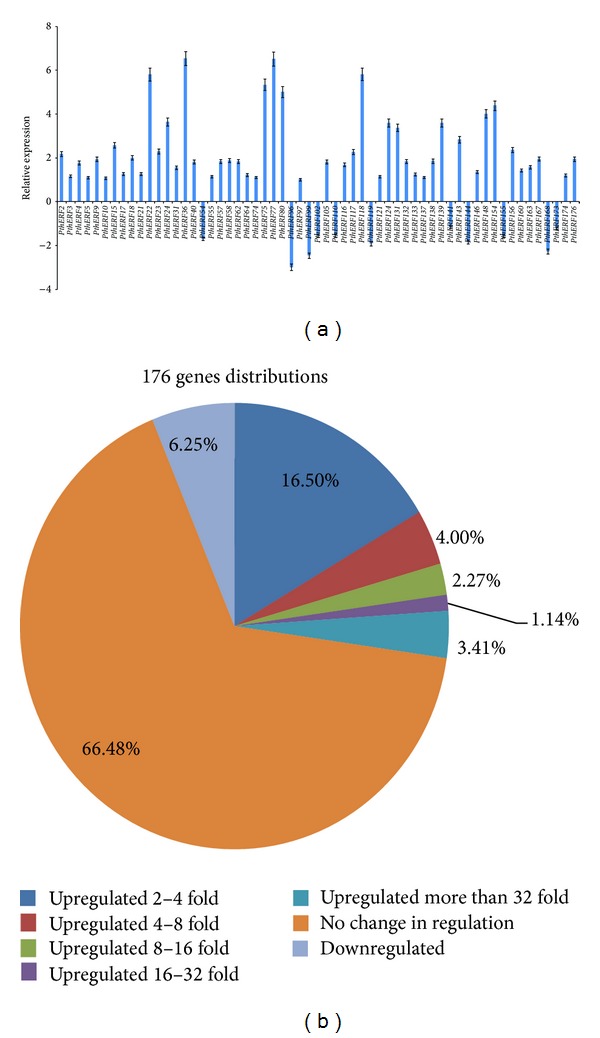

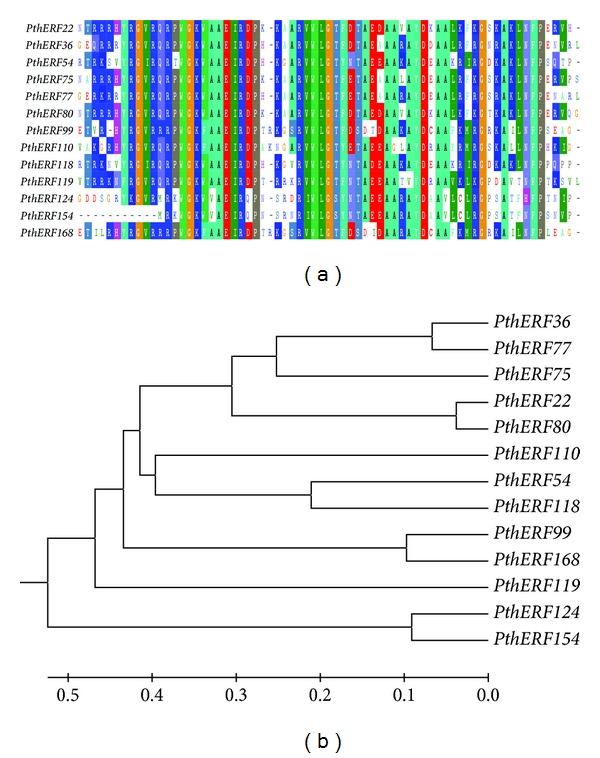

Using RT-PCR, 59 (33.52%) genes responded to high salinity stress in leaves were screened from 176 Populus ERF genes, and their expression patterns were displayed in Figure 1(a). Of these 59 genes, 48 (27.27%) were upregulated genes and 11 were (6.25%) downregulated genes. These 176 ERF genes distributions were shown in Figure 1(b). Thirteen ERF genes with full-length ORFs were selected for further study in this research. These genes were designated as PthERF22, 36, 54, 75, 77, 80, 99, 110, 118, 119, 124, 154, and 168, and their GenBank accession numbers were shown in Table 1. The ORFs encoded polypeptides of 135–498 amino acids, with MWs between 14.65 and 54.06 kDa and pI values between 4.64 and 9.67 (Table 2). These 13 genes were found to have conserved AP2/ERF domain based on the AP2/ERF domain (59 amino acids) of the tobacco ERF2 protein (Figure 2(a)). The phylogenetic relationships between these ERF genes were deduced from aligned sequences. The phylogenetic tree showed that these thirteen genes could be classified into four subgroups: subgroup 1 contained PthERF54, 99, 110, 118, and 168; subgroup 2 included PthERF22, 36, 75, 77, and 80; subgroup 3 consisted of PthERF124 and 154; and subgroup 4 comprised PthERF119 only (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 1.

Expression trends of 176 Populus ERF genes in response to NaCl stress in the leaves by RT-PCR analysis. Relative expression level was log2 transformed: >0: upregulation; =0: no change in regulation; <0: downregulation. (a) Expression patterns of 59 responsive PthERFs; (b) 176 ERF genes distributions: 66.48% were no change in regulation; 6.25% were downregulated; the rest were upregulated in different degrees.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 13 PthERFs proteins.

| Gene | cDNA length (bp) | Mature protein | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | PI | MW (KDa) | ||

| PthERF22 | 696 | 231 | 7.09 | 25.78 |

| PthERF36 | 1203 | 400 | 7.32 | 42.80 |

| PthERF54 | 768 | 255 | 8.18 | 29.21 |

| PthERF75 | 723 | 240 | 9.24 | 26.48 |

| PthERF77 | 1497 | 452 | 9.47 | 54.06 |

| PthERF80 | 561 | 186 | 9.67 | 20.97 |

| PthERF99 | 705 | 234 | 4.76 | 26.04 |

| PthERF110 | 780 | 259 | 8.10 | 28.46 |

| PthERF118 | 747 | 248 | 9.42 | 27.37 |

| PthERF119 | 966 | 321 | 6.39 | 36.45 |

| PthERF124 | 468 | 155 | 8.05 | 17.31 |

| PthERF154 | 408 | 135 | 4.93 | 14.65 |

| PthERF168 | 714 | 237 | 4.64 | 26.65 |

Figure 2.

Multiple alignments and phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequence of thirteen PthERFs. (a) Multiple sequence alignments of 13 PthERFs with ERF domain sequences. (b) Phylogenetic analysis of 13 PthERFs based on amino acid sequences.

3.2. Relative Abundances of ERFs in Roots, Stems, and Leaves

The relative abundance of the thirteen PthERFs was determined by calculating C T values for each PthERF in the leaves, stems, and roots under normal growth conditions according to real-time RT-PCR. PthERF75 with the lowest expression level in stems (highest delta-delta C T value) was used as a calibrator (designated as 1.0) to determine relative gene expression levels. Relative gene expression levels were log2 transformed and the results are shown in Table 3. There were notable differences in the abundance of these PthERFs expression in each tissue, particularly in the stems. The greatest differences among these PthERFs in transcript abundances when exposed to normal conditions were 113.7-fold in leaves in PthERF110, 702.6-fold in stems in PthERF118, and 3.76-fold in roots in PthERF54. PthERF75 was the gene of lowest expression level in leaves and stems, while PthERF168 was lowest in roots.

Table 3.

Relative mRNA abundance of ERF genes in different tissues under normal conditions.

| Gene | Relative abundance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | Stems | Leaves | |

| PthERF22 | 0.41 | 30.64 | 3.78 |

| PthERF36 | 0.79 | 26.47 | 6.97 |

| PthERF54 | 3.76 | 41.85 | 111.22 |

| PthERF75 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| PthERF77 | 0.21 | 7.14 | 1.84 |

| PthERF80 | 0.42 | 26.8 | 9.09 |

| PthERF99 | 0.24 | 42.7 | 38.01 |

| PthERF110 | 3.3 | 276.69 | 113.67 |

| PthERF118 | 3.27 | 702.55 | 61.23 |

| PthERF119 | 3.24 | 329.37 | 61.82 |

| PthERF124 | 0.22 | 83.77 | 46.88 |

| PthERF154 | 0.26 | 125.14 | 25.31 |

| PthERF168 | 0.04 | 60.85 | 108 .57 |

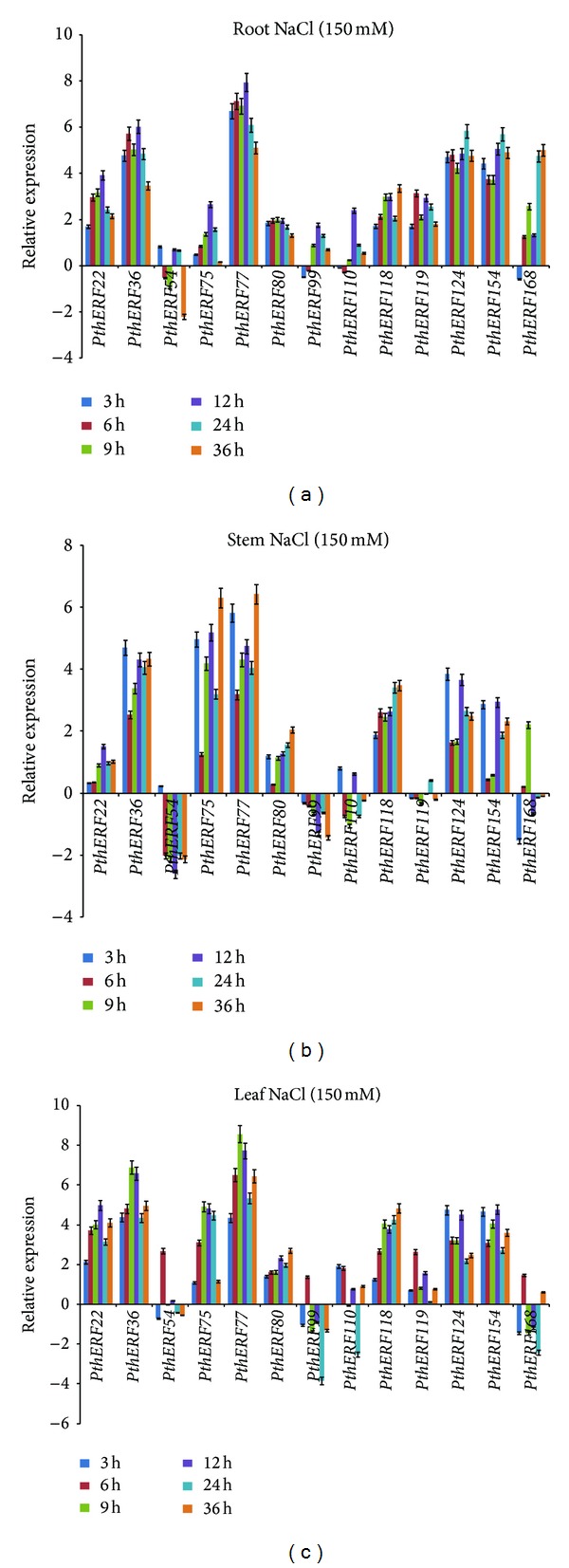

3.3. Expression Patterns of ERFs in Response to NaCl Stress

In roots, all the PthERFs (except PthERF99, 110, and 168) were highly upregulated at 3 h of NaCl stress, but then PthERF54 showed different expression pattern to other ERF genes at 6, 9, and 36 h. At 12 h, thirteen PthERFs reached or nearly reached their highest expression levels in roots, suggesting that PthERFs play important roles in salinity stress tolerance in roots (Figure 3(a)). In stem tissues, PthERF20, 36, 75, 77, 80, 118, 124, and 154 displayed similar expression pattern, and they were upregulated and highly expressed at each time point. PthERF119 was downregulated after 3 h of NaCl stress, but the expression of this gene was not significantly different from expression in the control stems during the treatment period. PthERF168 was significantly downregulated at 3 h of NaCl stress but was induced at 9 h. PthERF54, PthERF99, and PthERF110 were generally downregulated under NaCl treatment (Figure 3(b)). In leaves, the expression patterns of these thirteen ERF genes could be divided into two groups. One group contained PthERF54, 99, and 168, which were mainly downregulated but highly induced at 6 h. The other group genes were induced except PthERF110, which was downregulated at 24 h (Figure 3(c)). Interestingly, all of the 13 PthERFs were highly induced in leaves at 6 h.

Figure 3.

Spatial-temporal expression of 13 PthERFs under salt stress in different tissues. Relative expression level was log2 transformed: >0: upregulation; =0: no change in regulation; <0: downregulation; (a) in roots; (b) in stems; (c) in leaves.

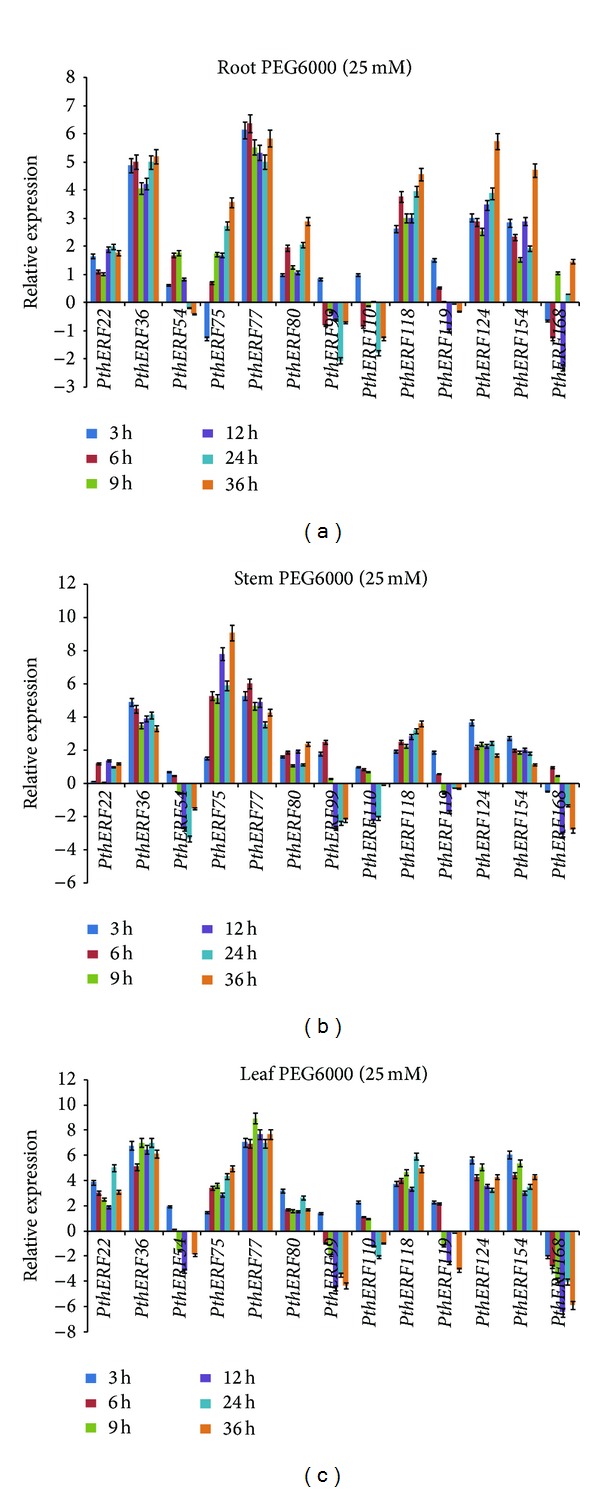

3.4. Expression Patterns of ERFs in Response to Drought Stress

In roots, all PthERF genes were significantly differentially regulated in response to drought stress. They were all induced at 3 h, except PthERF75 and PthERF168. PthERF99 and PthERF110 were downregulated by drought stress at the other time points, and other genes were generally upregulated. Specially, PthERF77 was significantly upregulated during the drought treatment period and reached its highest level at 6 h. PthERF168 showed different pattern to other genes, and it was highly downregulated at 12 h, but the express did not differ notably from the controls at other time points (Figure 4(a)). In stems, all PthERF genes (except PthERF168) were induced at 3 h. PthERF54, 99, 110, 119, and 168 were significantly downregulated at 12 h. The other genes generally showed similar expression patterns in which the expression levels in leaves were not significantly different during the drought treatment (Figure 4(b)). In leaves, PthERF168 was significantly downregulated under drought stress and decreased to its lowest level at 12 h. Other PthERFs were induced at 3 h, and eight genes were upregulated at all stress times. PthERF54, 99, 110, and 119 shared the similar expression pattern, and they were induced at early time points but downregulated at late stages. The results indicated that all these thirteen PthERFs play roles in the drought stress response in leaf tissue (Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

Spatial-temporal expression of 13 PthERFs under drought stress in different tissues. Relative expression level was log2 transformed: >0, upregulation; =0, no change in regulation; <0, downregulation: (a) in roots; (b) in stems; (c) in leaves.

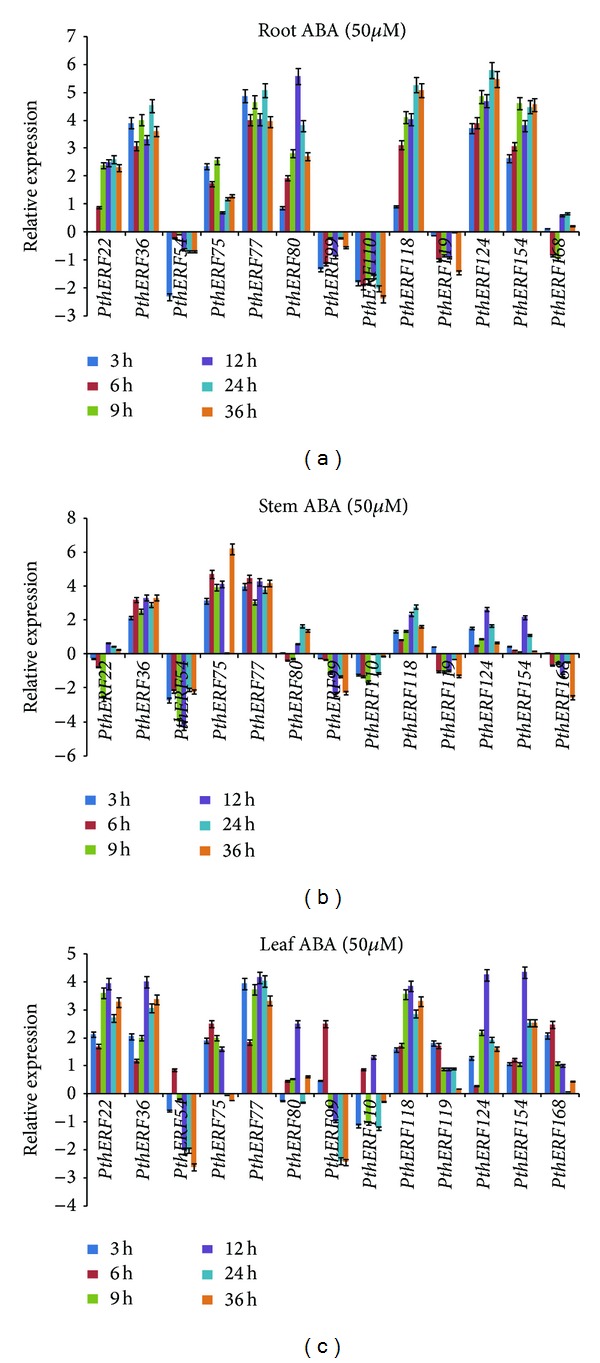

3.5. Expression Patterns of ERFs in Response to ABA

In roots, all PthERF genes generally reached their peaks in expression level at 24 h. PthERF22, 36, 75, 77, 80, 118, 124, and 154 were all highly induced during the treatment period, and PthERF54, 99, 110, and 119 were downregulated. PthERF168 was downregulated at 6 h and 9 h and upregulated at the other time points, but it did not differ significantly from controls during the whole ABA stress treatment (Figure 5(a)). In stems, PthERF36, 75, and 77 were highly induced by ABA treatment, but PthERF77 did not show discrepancy from controls at 24 h. PthERF80, 118, 124, and 154 showed similar expression patterns, and these genes were generally upregulated or did not differ significantly from the controls. The expressions of PthERF22, 54, 99, 110, 119, and 168 were generally downregulated throughout the treatment period (Figure 5(b)). In leaves, PthERF54, 99, and 110 were induced and generally reach the highest level at 6 h. At the other time points, PthERF54 and PthERF99 were significantly downregulated or were similar to the controls. PthERF110 was upregulated by ABA treatment at 6 h and 12 h. The highest expression levels of the remaining ten PthERFs occurred at 12 h, and these genes were significantly induced or did not differ significantly from the controls during the entire treatment time (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 5.

Spatial-temporal expression of 13 PthERFs under ABA treatment in different tissues. Relative expression level was log2 transformed: >0: upregulation; =0: no change in regulation; <0: downregulation; (a) in roots; (b) in stems; (c) in leaves.

4. Discussion

Plants are constantly experiencing various biotic and abiotic stresses. For this reason, they have developed specific signal transduction pathways and other molecular mechanisms that allow them to adapt to a variety of stresses by inducing specific sets of genes [23–25]. ERF proteins belong to one of the largest transcription factor families in plants [26]. Such a fact implicates that ERF proteins have crucial roles in regulating responses to environmental stresses and plant development. In the present study, 13 ERF transcription factor genes from di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra were detected. Since spatial-temporal expression pattern of a particular gene under a given set of conditions can suggest functionality of gene [27–30], and real-time RT-PCR was used to analyze these PthERFs expression patterns in response to salinity, drought, and ABA stresses.

In this study, we found that under normal conditions, the abundances of these PthERFs were noticeably different in roots, stems, and leaves (Table 3). Except PthERF54 and PthERF168, all of 13 PthERFs were highly expressed in stems as compared to either roots or leaves, especially PthERF118, whose expression was the highest in the stems. The expression level of PthERF118 in stem was 215 times of that in roots and 11.5 times in leaves. Such results suggest that the PthERFs may play roles mainly in stems rather than in roots and leaves. Previous studies have implicated that the expression of some ERF genes has tissue specific, such as Medicago sativa L. MsERF8 and rice OsEATB [31, 32], which are expressed in root and leaf tissues. Conversely, PthERF54 and PthERF168 were most abundant in leaves than in root and stem tissues, indicating that they may mainly function in leaves.

When being subjected to NaCl stress, most PthERFs were induced by high salinity and exhibited differential expression patterns (Figure 3), especially PthERF77, which was most highly upregulated among these genes in all tissues, roots, stems, and leaves. The results suggest that these PthERFs are all involved in the salinity stress response. Consistent with these observations, previous studies have shown that ERF genes regulate salt stress response and tolerance. These include but are not limited to SodERF3 in sugarcane [33], OsEREBP1 and OsEREBP2 in rice [34], HvRAF in barley [35], and IbERF1 and IbERF2 in sweet potato [36]. All these genes can directly confer salt tolerance to plants. In addition, some ERF genes are known to be responsive to salt, but their exact functions in salt stress response and tolerance remain unknown. For example, the expression of an ERF gene inrice, EsE1, was induced by salt stress [37]. In Solanum lycopersicum var. “Pusa Ruby,” the ERF gene SlERF68 was upregulated more than 17-fold during salt stress, and the other gene, SlERF80, was upregulated up to 400-fold during salt stress [7]. All above suggest that ERF family genes are involved in the salt stress response and may play important roles in high salinity stress tolerance.

Under drought stress, seven PthERF genes exhibit similar expression patterns to those under salt stress (Figure 4). Evidence that REFs can confer increased drought tolerance has been implicated in previous studies. These which include TSRF1 improve salt and drought tolerance of rice seedlings without growth retardation [38]. SodERF3 of sugarcane increases drought stress tolerance in tobacco [33]. Transgenic plants overexpressing OsDERF1 (OE) led to reduced tolerance to drought stress in rice at seedling stage, while knockdown of OsDERF1 expression conferred enhanced tolerance at seedling and tillering stages [39]. Consistent with the result, a previous study [7] also showed that the expression level of the ERF gene, SlERF5, in stems had decreased significantly in comparison to the controls after drought stress treatment, but the overexpressing SlERF5 transgenic plants showed increased resistance to drought stress. Therefore, the downregulation of PthERFs in response to drought stress may also be evidence that they play roles in drought tolerance. In this study, five PthERF genes, PthERF54, 99, 110, 119, and 168, were mainly downregulated in drought stress treatment (Figure 4).

The ABA signaling pathways are reported to comprise signal transducers and transcription factors [40, 41], and ABA plays a pivotal role in a variety of developmental processes and adaptive stress responses to environmental stimuli in plants. Interestingly, our result showed that all of the PthERFs were highly induced by ABA treatment in the leaves at 6 h and reached a peak at 6 h or 12 h (Figure 5). Presumably, the time lag is because the signal perception and transduction take time to trigger the genes with distance. The induction of ERF genes will impose regulation on their targets genes, which in turn can augment the stress adaptation and tolerance. When such a process is completed, the expression of ERF will be decreased. Some reports also showed that the transcription factors were highly induced at early stress period and then decreased [42–44]. In addition, most PthERFs were highly upregulated by ABA stress, implicating that PthERFs may be involved in ABA-dependent stress responses. The expression discrepancy of the same genes in various tissues in response to ABA suggests that ERFs have tissues specificity. For example, PthERF119 was upregulated responded to ABA treatment in leaves but downregulated in roots.

In general, PthERF36, 75, 77, 118, and 124 displayed similar expression pattern in response to abiotic stress treatment, indicating that these five genes may be involved in the same gene expression regulatory networks in response to stresses. Other PthERFs displayed different expression patterns in response to stress, suggesting that these genes may be involved in distinct gene regulation pathways.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, 13 PthERFs expression patterns have been constructed in different tissues of di-haploid Populus simonii × P. nigra in response to salinity stress, drought stress, and ABA treatment. The results showed that PthERFs can be induced by salinity, drought, and ABA, indicating that PthERFs were involved in salt and drought stress tolerance and are controlled by ABA. Further, these PthERF genes were more highly induced by NaCl, PEG, and ABA in roots and leaves than in stems, suggesting that these genes may play roles in stress responses in the roots and leaves but not stems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China (2013AA102701) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Project (DL12CA16).

Conflict of Interests

The authors have declared no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Xu Z-S, Chen M, Li L-C, Ma Y-Z. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2011;53(7):570–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharoni AM, Nuruzzaman M, Satoh K, et al. Gene structures, classification and expression models of the AP2/EREBP transcription factor family in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2011;52(2):344–360. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu L, Liu S. Genome-Wide identification and phylogenetic analysis of the ERF gene family in cucumbers. Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2011;34(4):624–633. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572011005000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhuang J, Chen J-M, Yao Q-H, et al. Discovery and expression profile analysis of AP2/ERF family genes from Triticum aestivum. Molecular Biology Reports. 2011;38(2):745–753. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Li J, Wang H, Fu Z, Liu Z, Yu Y. Identification and expression analysis of ERF transcription factor genes in petunia during flower senescence and in response to hormone treatments. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2011;62(2):825–840. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licausi F, Giorgi FM, Zenoni S, Osti F, Pezzotti M, Perata P. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily in Vitis vinifera. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 719) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma MK, Kumar R, Solanke AU, Sharma R, Tyagi AK, Sharma AK. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript profiling of ERF family genes during development and abiotic stress treatments in tomato. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2010;284(6):455–475. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wessler SR. Homing into the origin of the AP2 DNA binding domain. Trends in Plant Science. 2005;10(2):54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell. 1995;7(2):173–182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, et al. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 1998;10(8):1391–1406. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JM, Park C-J, Lee S-B, Ham B-K, Shin R, Paek K-H. Overexpression of the tobacco Tsi1 gene encoding an EREBP/AP2-type transcription factor enhances resistance against pathogen attack and osmotic stress in Tobacco . Plant Cell. 2001;13(5):1035–1046. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu Y-Q, Wildermuth MC, Chakravarthy S, et al. Tomato transcription factors Pti4, Pti5, and Pti6 activate defense responses when expressed in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 2002;14(4):817–831. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thara VK, Tang X, Gu YQ, Martin GB, Zhou J-M. Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato induces the expression of tomato EREBP-like genes Pti4 and Pti5 independent of ethylene, salicylate and jasmonate. Plant Journal. 1999;20(4):475–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kizis D, Pagès M. Maize DRE-binding proteins DBF1 and DBF2 are involved in rab17 regulation through the drought-responsive element in an ABA-dependent pathway. Plant Journal. 2002;30(6):679–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenzo O, Piqueras R, Sánchez-Serrano JJ, Solano R. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2003;15(1):165–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regier N, Frey B. Experimental comparison of relative RT-qPCR quantification approaches for gene expression studies in poplar. BMC Molecular Biology. 2010;11, article 57 doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Jin J, Tang L, et al. PlantTFDB 2.0: update and improvement of the comprehensive plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(1):D1114–D1117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UniProt. April 2013, http://www.uniprot.org/

- 20.ORF Finder. April 2013, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html.

- 21.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, et al. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31(13):3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietz K-J, Vogel MO, Viehhauser A. AP2/EREBP transcription factors are part of gene regulatory networks and integrate metabolic, hormonal and environmental signals in stress acclimation and retrograde signalling. Protoplasma. 2010;245(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Seki M. Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2003;6(5):410–417. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Huang Z, Xie B, et al. The ethylene-, jasmonate-, abscisic acid- and NaCl-responsive tomato transcription factor JERF1 modulates expression of GCC box-containing genes and salt tolerance in tobacco. Planta. 2004;220(2):262–270. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray S, Agarwal P, Arora R, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK. Expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family during reproductive development and abiotic stress conditions in rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica) Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2007;278(5):493–505. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh A, Baranwal V, Shankar A, et al. Rice phospholipase A superfamily: organization, phylogenetic and expression analysis during abiotic stresses and development. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030947.e30947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh A, Giri J, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK, Pandey GK. Protein phosphatase complement in rice: Genome-wide identification and transcriptional analysis under abiotic stress conditions and reproductive development. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 435) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh A, Pandey A, Baranwal V, Kapoor S, Pandey GK. Comprehensive expression analysis of rice phospholipase D gene family during abiotic stresses and development. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2012;7:847–855. doi: 10.4161/psb.20385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen T, Yang Q, Gruber M, et al. Expression of an alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) ethylene response factor gene MsERF8 in tobacco plants enhances resistance to salinity. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(5):6067–6075. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1421-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi W, Sun F, Wang Q, et al. Rice ethylene-response AP2/ERF factor OsEATB restricts internode elongation by down-regulating a gibberellin biosynthetic gene. Plant Physiology. 2011;157(1):216–228. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trujillo LE, Sotolongo M, Menéndez C, et al. SodERF3, a novel sugarcane ethylene responsive factor (ERF), enhances salt and drought tolerance when overexpressed in tobacco plants. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49(4):512–525. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serra TS, Figueiredo DD, Cordeiro AM, et al. OsRMC, a negative regulator of salt stress response in rice, is regulated by two AP2/ERF transcription factors. Plant Molecular Biology. 2013;82(4-5):439–455. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung J, Won SY, Suh SC, et al. The barley ERF-type transcription factor HvRAF confers enhanced pathogen resistance and salt tolerance in Arabidopsis . Planta. 2007;225(3):575–588. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y-H, Jeong JC, Park S, Lee H-S, Kwak S-S. Molecular characterization of two ethylene response factor genes in sweetpotato that respond to stress and activate the expression of defense genes in tobacco leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2012;169(11):1112–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Li Z, Quan R, Li G, Wang R, Huang R. An AP2 domain-containing gene, ESE1, targeted by the ethylene signaling component EIN3 is important for the salt response in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiology. 2011;157(2):854–865. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quan R, Hu S, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Huang R. Overexpression of an ERF transcription factor TSRF1 improves rice drought tolerance. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2010;8(4):476–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wan L, Zhang J, Zhang H, et al. Transcriptional activation of OsDERF1 in OsERF3 and OsAP2-39 negatively modulates ethylene synthesis and drought tolerance in rice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9, article e25216) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkelstein RR, Gampala SSL, Rock CD. Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell. 2002;14:S15–S45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Himmelbach A, Yang Y, Grill E. Relay and control of abscisic acid signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2003;6(5):470–479. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.García MNM, Giammaria V, Grandellis C, Téllez-Iñón MT, Ulloa RM, Capiati DA. Characterization of StABF1, a stress-responsive bZIP transcription factor from Solanum tuberosum L. that is phosphorylated by StCDPK2 in vitro. Planta. 2012;235(4):761–778. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ying S, Zhang D-F, Fu J, et al. Cloning and characterization of a maize bZIP transcription factor, ZmbZIP72, confers drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis . Planta. 2012;235(2):253–266. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao S-Q, Chen M, Xu Z-S, et al. The soybean GmbZIP1 transcription factor enhances multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 2011;75(6):537–553. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9738-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]