Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to determine the incidence of early stasis in radioembolization using resin yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres, to evaluate potential contributing factors, and to review initial imaging outcomes.

Methods

Patients in whom early stasis occurred were compared with those in whom complete delivery was achieved for tumour type and vascularity, tumour : normal liver ratio (T : N ratio) at technetium-99m-macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m-MAA) angiography, previous intra-arterial therapy, and infusion site (left, right or whole liver). Tumour response was evaluated at 3 months and defined according to whether a partial response and stable disease versus progressive disease were demonstrated.

Results

A total of 71 patients underwent 128 Y-90 infusions in which 26 (20.3%) stasis events occurred. Hypervascular and hypovascular tumours had similar rates of stasis (17.4% versus 27.8%; P = NS). The mean ± standard deviation T : N ratio was 3.03 ± 1.54 and 3.66 ± 2.79 in patients with and without stasis, respectively (P = NS). Stasis occurred in 14 of 81 (17.3%) and 12 of 47 (25.5%) infusions following previous intra-arterial therapy and in therapy-naïve territories, respectively (P = NS). Early stasis occurred in 15 of 41 (36.6%) left, 10 of 65 (15.4%) right and one of 22 (4.5%) whole liver infusions (P < 0.001). Rates of partial response and stable disease were similar in the stasis (88.3%) and non-stasis (76.0%) groups (P = NS).

Conclusions

Early stasis occurred in approximately 20% of infusions with similar incidences in hyper-and hypovascular tumours. Whole-liver therapy reduced the incidence of stasis. Stasis did not appear to affect initial imaging outcomes.

Introduction

There are two yttrium-90 (Y-90) radioembolization devices commonly used in clinical practice. The TheraSphere® (MDS Nordion, Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) is a glass microsphere which is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1 SIR-Spheres® (Sirtex Medical Ltd, North Sydney, NSW, Australia) are resin microspheres which are FDA-approved for the treatment of metastatic colorectal carcinoma with concomitant fludarabine.2 Although these devices both emit beta radiation to induce tumour necrosis following locoregional delivery, they are quite different: most importantly, the glass microspheres contain a much greater density of Y-90 per bead than do the resin microspheres. The net result is that complete dose delivery is always accomplished with glass microspheres without detectable angiographic evidence of embolization.3 Given the lower density of Y-90 per bead afforded by resin microspheres, full delivery is not always possible as the target artery can develop stasis prior to the completion of infusion.4

Although stasis with resin microspheres is an anecdotally known phenomenon, the exact incidence of this event and the factors that contribute to it are not described in the literature. Greater understanding of this event is valuable for multiple reasons. Stasis prevents the delivery of the prescribed activity and can result in non-target infusion with toxic dose administration to extrahepatic tissues.5,6 As with other types of radiation therapy, resin microspheres are ordered at a specified activity level with the goal of administering a prescribed dose to the targeted tumour(s). The brachytherapy effect of Y-90 microspheres allows the delivery of a greater dose to the targeted liver tumour(s) than does external beam radiation.7 However, early stasis may potentially lead to early tumour progression secondary to suboptimal dose delivery. The primary goals of this study were to define the incidence of stasis in the study patient population and to evaluate potential contributing factors. Secondary goals were to evaluate imaging responses following treatment and to compare findings in the groups in which complete dose delivery was and was not achieved.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Thomas Jefferson University (Philadelphia, PA, USA). All patients treated with resin Y-90 microspheres between January 2007 and February 2010 were included. The criteria for treatment with Y-90 microspheres required that patients demonstrated: (i) confirmed unresectable liver-dominant disease; (ii) an East Coast Oncology Group performance status of 0–2; (iii) adequate liver function (bilirubin of <1.8 mg/dL), haematologic parameters (granulocyte and platelet counts of >1500/microliter and >50 000/microliter, respectively, per μL blood) and renal function (creatinine of <2.5 mg/dL), and (iv) the ability to undergo selective hepatic angiography.

Criteria that excluded patients from treatment included: (i) a life expectancy of <2 months; (ii) a side branch flow to the gastrointestinal tract that could not be avoided or embolized, and (iii) an estimated lung dose of ≥30 Gy.

Yttrium-90 treatment

Baseline cross-sectional imaging, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, was obtained based on the primary tumour aetiology. All patients underwent mapping arteriography with side-branch embolization performed as previously described.6,8 Following side-branch embolization, technetium-99m-macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m-MAA) was infused into the target arteries to estimate the lung-shunt fraction and evaluate for extrahepatic flow. If outcomes were satisfactory, the first treatment was administered 10–21 days later. The dose prescribed was based on body surface area (BSA) and calculated as:

where Vtumour and Vliver represent the volume of tumour and total liver, respectively, and A represents radioactivity in GBq (gigabecquerel). Body surface area in square metres was calculated as 0.20247 × height (m)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425.

Prescribed activity was calculated according to the patient's weight, height and tumour volume, and in line with the patient's history of previous therapy. In patients who had previously received either systemic chemotherapy or intra-arterial liver-directed therapy (chemo-or immunoembolization), the dose was reduced by 25%.9,10 Patients were treated with lobar or whole-liver infusion based on anatomy and tumour burden. If untreated liver remained or if patients underwent whole-liver therapy in multiple fractions, the second treatment was performed 4–6 weeks after the initial infusion.

A standard practice for resin microsphere infusion was followed by all operators. Infusions were performed by four board-certified interventional radiologists with 5–17 years of experience (DJE, JWM, CFG, DBB). The radioactive microsphere dose was pushed through the proprietary delivery kit with small aliquots of sterile water. After flushing the line clear, 2–3-mL aliquots of non-ionic contrast [Ioversol 320 (Covidien, Inc., Hazelwood, MO, USA) or Iodixanol 320 (GE Healthcare, Inc., Waukesha, WI, USA) in patients with a glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min] were injected and cleared with sterile water to ensure continued antegrade flow after each pulse of radioactive microsphere delivery. Sterile water infusions were limited to the volume necessary to infuse and clear the microspheres and contrast. When the delivery vial was clear, the vial was emptied by priming the inlet line with air (the ‘air shot’). For the purpose of this study, early stasis was defined as an infusion in which the delivery of resin microspheres was halted as a result of a lack of antegrade flow at angiography during infusion. In all cases of early stasis, residual microspheres remained in the delivery vial and the infusion was halted prior to the air shot. Standard post-procedure measurements of the residual dose within the vial were obtained in all patients using a survey meter (portable ion chamber radiation monitor model TBM-IC-AJI; Technical Associates, Canoga Park, CA, USA).

Factors contributing to stasis

Factors that might potentially contribute to early stasis were identified and evaluated. Relationships were tested using chi-squared, Fisher's exact or t-tests. Factors included: (i) tumour type; (ii) vascularity (hypo-versus hypervascular)11 based on angiographic appearance; (iii) a low tumour : normal liver ratio (T : N ratio) at scintigraphic imaging following Tc-99m-MAA angiography; (iv) previous intra-arterial therapy, and (v) infusion site (left, right or whole liver).

Potential effect of stasis on early outcomes

The delivery of an incomplete dose could potentially lead to the failure of treatment and the early progression of disease. The earliest time at which a measurable response to Y-90 therapy can be obtained is at 3 months following treatment.12,13 As a primary goal of all intra-arterial therapies is to arrest disease progression, incidences of intrahepatic progressive disease versus partial response and stable disease at 3 months were evaluated in the stasis and non-stasis groups using CT or MRI according to the RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumours) framework.

Results

Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-one patients received 128 infusions during 79 cycles of therapy. Patient ages ranged from 23 years to 91 years [median: 61 years; mean ± standard deviation (SD) 63 ± 12 years]. Disease aetiology included uveal melanoma (n = 43), colorectal carcinoma (n = 12), HCC (n = 5), breast carcinoma (n = 3), neuroendocrine tumour (n = 2), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 2), Merkel cell carcinoma (n = 1), prostate adenocarcinoma (n = 1), gastric carcinoma (n = 1) and oesophageal carcinoma (n = 1). The patients underwent one to four infusions (mean ± SD: 1.7 ± 0.6; median = 2). One, two, three and four infusions were performed in 23, 41, five and two patients, respectively. Prior to treatment with Y-90, 47 of 71 (66.2%) patients had undergone previous intra-arterial therapy and another 20 of the 71 (28.2%) patients had exhausted first-and, when applicable, second-line therapeutic regimens. The mean ± SD and median prescribed activity was 0.71 ± 0.30 GBq and 0.68 GBq (range: 0.2–1.6 GBq). The mean ± SD and median delivered activity was 0.66 ± 0.32 GBq and 0.61 GBq (range: 0.07–1.60 GBq).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study group

| Characteristic | n |

|---|---|

| Patients | 71 |

| Male | 33 |

| Female | 38 |

| Malignancy | |

| Uveal melanoma | 43 |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 12 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 5 |

| Breast carcinoma | 3 |

| Neuroendocrine tumour | 2 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 |

| Other | 4 |

| Previous intra-arterial therapy | |

| Yes | 81 |

| No | 47 |

| Infusion site | |

| Left | 41 |

| Right | 65 |

| Whole liver | 22 |

Incidence of early stasis

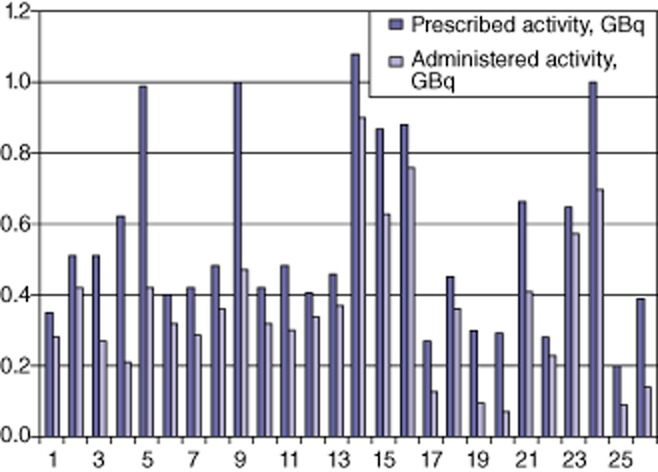

Early stasis developed during 26 of 128 (20.3%) infusions. The mean ± SD and median percentages of prescribed activity delivered in this group were 64.5 ± 19.3% and 70.0% (range: 24.4%–87.1%). The relative values of prescribed and administered activity in the stasis group are shown in Fig. 1. In the infusions without early stasis (103/128, 79.7%), the mean ± SD and median percentages of prescribed activity delivered were 99.5 ± 5% and 100% (range: 83–108%). Thresholds of delivery in the early stasis and non-stasis groups are outlined in Table 2. The upper range of delivery in the early stasis group (86.9%) overlapped one patient in the non-stasis group, in whom an infusion of 83.2% of the prescribed activity was achieved despite the completion of the procedure including the air shot.

Figure 1.

Prescribed and administered activity in the 26 instances of early stasis

Table 2.

Delivery of prescribed yttrium-90 activity administered in infusions in which early stasis did and did not occur

| Delivery achieved | Early stasis infusions (n = 26), n | No stasis infusions (n = 102), n |

|---|---|---|

| <50% | 7 | 0 |

| 50–75% | 13 | 0 |

| 76–90% | 6 | 4 |

| 90–100% | 0 | 99 |

Potential contributing factors

The stratification of stasis by tumour type is outlined in Table 3. Outcomes by tumour vascularity in the entire cohort are presented in Table 4. In the entire cohort, hypovascularity did not predict stasis during infusion (17.4% versus 27.8%; P = 0.22, d.f. = 1). At pre-procedure scintigraphic imaging, the mean ± SD T : N ratio was 3.03 ± 1.54 in patients with early stasis and 3.66 ± 2.79 in those without early stasis (d.f. = 71, t = 1.55, P = NS). Eighty-one of the 128 infusions (63.3%) were performed in a region that had previously been treated with intra-arterial therapy. Early stasis occurred in 14 of 81 (17.3%) infusions compared with 12 of 47 (25.6%) in territories that were naïve to intra-arterial treatment (P = NS). Early stasis occurred in 15 of 41 (36.6%) left lobe infusions, 10 of 65 (15.4%) right lobe infusions and one of 22 (4.5%) whole-liver infusions (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Incidence of stasis by tumour type

| Pathology | Patients, n | Infusions, n | Stasis events, n | Incidence of stasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uveal melanoma | 43 | 78 | 12 | 15.4% |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 12 | 19 | 7 | 36.8% |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 5 | 7 | 1 | 14.3% |

| Breast | 3 | 7 | 1 | 14.3% |

| Carcinoid | 2 | 5 | 3 | 60.0% |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0% |

| Merkel cell lymphoma | 1 | 2 | 2 | 100% |

| Prostate | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Gastric | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Oesophageal | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0% |

Table 4.

Outcomes by tumour vascularity

| Vascularity | Patients, n | Infusions, n | Stasis events, n | Incidence of stasisa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypovascular | 21 | 36 | 10 | 27.8% |

| Hypervascular | 50 | 92 | 16 | 17.4% |

The difference in the incidence of stasis between hypovascular and hypervascular tumours was not statistically significant.

Imaging outcomes

In the entire cohort at the initial follow-up imaging after one cycle of therapy, partial response was present in 13 (16.5%), stable disease was present in 50 (63.3%) and progressive disease was identified in 16 (20.2%) patients. Imaging outcomes by group are outlined in Table 5. In the early stasis group, progression of disease was present following three of 25 (12.0%) cycles of therapy. Partial response or stable disease was present following 22 of 25 (88.0%) cycles of therapy. In the non-progressive disease subgroup, three of 22 cycles (13.6%) achieved a partial response and 19 of 22 (86.4%) achieved stable disease. In the non-stasis group, progression of disease was present after 13 of 54 (24.1%) treatment cycles. Partial response or stable disease was present following 41 of 54 (75.9%) cycles of treatment. Ten of 41 (24.4%) patients in this subgroup demonstrated a partial response and 31 of 41 (75.6%) achieved stable disease. The early stasis group demonstrated a rate of disease control (88.3%) similar to that in patients who received the entire vial of spheres (76.0%) (P = NS).

Table 5.

Initial imaging findings in the early stasis and complete delivery groupsa

| Response | Early stasis infusions, n | No stasis infusions, n |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive disease | 3/25 | 13/54 |

| Stable disease/partial response | 22/25 | 41/54 |

| Partial response | 3/25 | 10/54 |

| Stable disease | 19/25 | 31/54 |

The rate of intrahepatic progression was similar between patient groups (P = 0.17).

Discussion

There are significant differences between the Y-90 agents currently available. Each has limitations as currently configured. Resin microspheres range in size from 20 μm to 60 μm and contain 50 Bq/particle, whereas glass microspheres measure 20–30 μm in size and contain 2500 Bq/particle.14 As a result, 3-GBq vials of resin and glass microspheres contain up to 80 × 106 and 1.2 × 106 spheres, respectively. These differences contribute to the limitations of each device. Glass microspheres are non-embolic and virtually no vascular changes are identified following infusion.3 As a result, issues with early stasis are non-existent and it is easier to deliver an equivalent or greater amount of activity using glass rather than resin microspheres. Outcomes with glass microspheres have been most impressive in patients with limited tumour burdens.15,16 Bangash et al. studied the use of glass microspheres in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Survival rates in patients with, respectively, <25% and >25% tumour burdens were 9.4 months and 2.0 months.15 Patients with colorectal cancer treated with glass microspheres showed a similar discrepancy in survival rates as patients with <25% and >25% replacement survived 18.7 months and 5.2 months, respectively.16 In a pilot study exploring the potential treatment of greater disease burdens, Lewandowski et al. treated 50 patients with glass microspheres that were allowed to decay for 2–3 days longer while maintaining the same target dose of 120 Gy.14 This approach led to the infusion of a larger number of microspheres to achieve the same administration. This study demonstrated reasonable safety and efficacy, and obtained improved results in larger tumours.14

The weakness of glass microspheres should theoretically imply the strength of resin microspheres. Coverage of the entire arterial supply of the targeted tumour(s) is less challenging, even for larger masses. The principal limitation of resin Y-90 microspheres is that early stasis in the infused artery can occur prior to complete dose delivery. Murthy et al. described stasis that prematurely terminated six of 19 infusions of resin microspheres.4 Outcomes in the present study indicated that approximately 20% of infusions are halted by angiographic stasis prior to complete dose delivery. The maximum delivered activity in any single case in which early stasis occurred was 86.9%; in half the patients, <75% of the intended activity was administered prior to stasis. By comparison, 96.0% of completed infusions resulted in the administration of >90% of the prescribed activity. Given the strengths and weaknesses of the devices currently available, it is likely that the optimal radioembolic in terms of Y-90 loading density and embolic potential would be a hybrid of the glass and resin devices in present use.

When stasis events were analysed according to tumour type, no clear patterns were identified. Although a comparison of outcomes in patients with, respectively, classically hypervascular tumours (uveal melanoma) and classically hypovascular tumours (colorectal cancer) yielded a significant difference in incidences of stasis, it is important to note that stasis still developed in 15.4% of uveal melanoma patients and was also seen in other hypervascular pathologies, such as HCC and carcinoid tumours. Further, when the entire cohort was assessed according to vascularity, no significant difference in the incidence of stasis by the presence or absence of hypervascularity emerged. A relative measure of tumour vascularity is the T : N ratio. This measure has been used to estimate ability to deliver resin Y-90 microspheres.10 The present authors hypothesized that the T : N ratio would be lower in patients reaching early stasis as hypervascular tumours with a higher T : N ratio would absorb more microspheres, leaving the lobar arteries patent. However, the T : N ratio was similar in patients reaching early stasis and those who achieved complete infusion.

A number of patients in the present series had previously undergone intra-arterial therapy with chemo-or immunoembolization, using gelfoam as the embolic agent.17 This metric was chosen for evaluation as recanalization rates following intra-arterial therapies can vary, ranging from 56% to 83% depending on the technique used.18,19 Despite multiple treatments in targeted territories prior to Y-90 therapy, no significant differences emerged in the facility with which spheres could be delivered in comparison with that in treatment-naïve arteries.

The final potential factor investigated in the present study was infusion location. The incidence of early stasis was significantly lower in whole-liver infusions compared with left or right lobe infusions. Early stasis occurred in only one whole-liver infusion. Sixteen of the 22 whole-liver infusions performed in the present patient group were fractionated so that patients underwent infusion of the entire liver twice with half the prescribed dose given at each visit. The method used to prescribe activity utilizes the patient's BSA and the ratio of tumour to liver volume to determine the prescription. Although lobar infusions are almost universally targeted for completion in a single visit, the fractionating of whole-liver treatments in the majority of patients undergoing this technique results in the halving of infusion activity, which is likely to have contributed to the lower incidence of early stasis in whole-liver treatments compared with lobar infusions.

Understanding of the ideal dosimetry for radioembolization with resin microspheres continues to evolve. The present study utilized the BSA method to calculate prescribed activity, which is the recommended approach.9,10 Dose reduction is a topic of potential debate, although it is widely used in practice. Kennedy et al. described the alteration of prescribed activity using the BSA method in 491 of 500 (98.2%) infusions.10 Concern for liver tolerance secondary to previous therapy and a low T : N ratio were included as two primary reasons for adjustment. Although the standardization of dose reduction is suboptimal, this technique is used in clinical practice to calculate an appropriate activity prescription with resin microspheres in heavily pretreated patients, as the majority of the present population were. Patients presenting with normal liver function following previous therapy can be at risk for toxicity from therapy. Hepatic steatosis and fibrosis following systemic therapy are commonly present after one treatment regimen in the setting of normal liver function tests.20,21 Piana et al. described a significantly increased risk for hepatic toxicity in patients undergoing resin microsphere administration who had previously undergone intra-arterial therapy.22 Given the palliative nature of treatment in this salvage group, dose reduction was reasonable in these patients.

In the current series, the possibility that incomplete dose delivery would predispose patients to immediate treatment failure and the progression of disease was of concern, although the present authors acknowledge that some patients progress despite the clinically successful delivery of therapy. Incidences of progressive disease in both groups were statistically similar, although an overall lower percentage of patients in the stasis group were found to have progressed at 3 months. A time-point at 3 months from treatment was selected for this measure because outcomes of Y-90 therapy take longer to evolve compared with those of chemoembolization and the 3-month time-point is typically the earliest at which responses can be discerned.12,13 The lack of early progression, if it proves durable, may suggest that the ischaemia associated with arterial stasis assists in achieving tumour necrosis even when dose delivery is not maximized.

The present study has limitations. The retrospective construct resulted in a varied patient group with outcomes tracked to 3 months. However, given the mix of diagnoses in the patient group, it was considered that initial failures should be targeted in this initial effort. The present series represents a salvage population. Other reports in similar mixed patient groups treated with salvage radioembolization have reported mean overall survival of 8–12 months.23,24 Based on the radiographic findings and survival in other studies, imaging at 3 months should be predictive of the future direction of these patients.12,13 The present study did not quantify all chemotherapy regimens administered to patients or the date of the last chemotherapy, although this may have contributed to the occurrence of stasis. Additionally, the potential for spasm resulting from the infusion of sterile water and/or the microspheres is unknown. Although stasis is an accepted endpoint for the discontinuance of infusion, maximal benefit may perhaps be obtained at an earlier stage of occlusion, such as by pruning of the peripheral arteries. The relative contributions of ischaemia and brachytherapy with reference to resin microspheres are unknown. Stasis as an endpoint remains controversial, even in the more established chemoembolization literature.25

In summary, early stasis occurred in 20.3% of infusions in the present series during resin microsphere administration. Early stasis was identified in both hyper-and hypovascular tumours and the presence of prominent tumour vascularity did not eliminate the potential for early stasis. However, stasis did not increase the risk for progression at initial follow-up, which implies that patients who develop stasis during the first of two planned treatment sessions can potentially derive benefit from the second procedure. The performance of whole-liver infusions significantly decreased the risk for early stasis and may be an optimal strategy in heavily pretreated patients.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Ibrahim S, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of longterm outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:52–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray B, Van Hazel G, Hope M, Burton M, Moroz P, Anderson J, et al. Randomized trial of SIR-Spheres plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone for treating patients with liver metastases from primary large bowel cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1711–1720. doi: 10.1023/a:1013569329846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato K, Lewandowski RJ, Bui JT, Omary R, Hunter RD, Kulik L, et al. Treatment of unresectable primary and metastatic liver cancer with yttrium-90 microspheres (TheraSphere): assessment of hepatic arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:522–529. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy R, Xiong H, Nunez R, Cohen AC, Barron B, Szklaruk J, et al. Yttrium 90 resin microspheres for the treatment of unresectable colorectal hepatic metastases after failure of multiple chemotherapy regimens: preliminary results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:937–945. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000161142.12822.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murthy R, Brown DB, Salem R, Meranze SG, Coldwell DM, Krishnan S, et al. Gastrointestinal complications associated with hepatic arterial yttrium-90 microsphere therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Gates VL, Nutting CW, Murthy R, Rose SC, et al. Research reporting standards for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewandowski RJ, Geschwind JF, Liapi E, Salem R. Transcatheter intra-arterial therapies: rationale and overview. Radiology. 2011;259:641–657. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewandowski RJ, Sato KT, Atassi B, Ryu RK, Nemcek AA, Kulik L, et al. Radioembolization with 90Y microspheres: angiographic and technical considerations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:571–592. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9064-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy A, Nag S, Salem R, Murthy R, McEwan AJ, Nutting C, et al. Recommendations for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies using yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy: a consensus panel report from the radioembolization brachytherapy oncology consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy AS, McNeillie P, Dezarn WA, Nutting C, Sangro B, Wertman D, et al. Treatment parameters and outcome in 680 treatments of internal radiation with resin 90Y-microspheres for unresectable hepatic tumours. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato KT, Omary RA, Takehana C, Ibrahim S, Lewandowski RJ, Ryu RK, et al. The role of tumour vascularity in predicting survival after yttrium-90 radioembolization for liver metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1564–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keppke AL, Salem R, Reddy D, Huang J, Jin J, Larson AC, et al. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma after treatment with yttrium-90 microspheres. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:768–775. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller FH, Keppke AL, Reddy D, Huang J, Jin J, Mulcahy MF, et al. Response of liver metastases after treatment with yttrium-90 microspheres: role of size, necrosis, and PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:776–783. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewandowski RJ, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Mulcahy MF, Sato KT, Kulik LM, et al. Optimization of radioembolic effect with extended-shelf-life yttrium-90 microspheres: results from a pilot study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bangash AK, Atassi B, Kaklamani V, Rhee TK, Yu M, Lewandowski RJ, et al. 90Y radioembolization of metastatic breast cancer to the liver: toxicity, imaging response, survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, Ibrahim SM, Sato KT, Ryu RK, Atassi B, et al. Radioembolization of colorectal hepatic metastases using yttrium-90 microspheres. Cancer. 2009;115:1849–1858. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto A, Chervoneva I, Sullivan KL, Eschelman DJ, Gonsalves CF, Mastrangelo MJ, et al. High-dose immunoembolization: survival benefit in patients with hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma. Radiology. 2009;252:290–298. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2521081252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erinjeri JP, Salhab HM, Covey AM, Getrajdman GI, Brown KT. Arterial patency after repeated hepatic artery bland particle embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.12.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geschwind JF, Ramsey DE, Cleffken B, van der Wal BC, Kobeiter H, Juluru K, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of liver tumours: effects of embolization protocol on injectable volume of chemotherapy and subsequent arterial patency. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s00270-002-2524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Ribero D, Wu TT, Zorzi D, Hoff PM, et al. Chemotherapy regimen predicts steatohepatitis and an increase in 90-day mortality after surgery for hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2065–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karoui M, Penna C, Amin-Hashem M, Mitry E, Benoist S, Franc B, et al. Influence of preoperative chemotherapy on the risk of major hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2006;243:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193603.26265.c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piana PM, Gonsalves CF, Sato T, Anne PR, McCann JW, Bar-Ad V, et al. Toxicities after radioembolization with yttrium-90 SIR-Spheres: incidence and contributing risk factors at a single centre. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans KA, Richardson MG, Pavlakis N, Morris DL, Liauw W, Bester L. Survival outcomes of a salvage patient population after radioembolization of hepatic metastases with yttrium-90 microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuart JE, Tan B, Myerson RJ, Garcia-Ramirez J, Goddu SM, Pilgram TK, et al. Salvage radioembolization of liver-dominant metastases with a resin-based microsphere: initial outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1427–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewandowski RJ, Wang D, Gehl J, Atassi B, Ryu RK, Sato K, et al. A comparison of chemoembolization endpoints using angiographic versus transcatheter intra-arterial perfusion/MR imaging monitoring. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1249–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]