Abstract

Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS) is a rare disorder of enteric smooth muscle function affecting the intestine and bladder. Patients with this severe phenotype are dependent on total parenteral nutrition and urinary catheterization. The cause of this syndrome has remained a mystery since Berdon's initial description in 1976. No genes have been clearly linked to MMIHS. We used whole-exome sequencing for gene discovery followed by targeted Sanger sequencing in a cohort of patients with MMIHS and intestinal pseudo-obstruction. We identified heterozygous ACTG2 missense variants in 15 unrelated subjects, ten being apparent de novo mutations. Ten unique variants were detected, of which six affected CpG dinucleotides and resulted in missense mutations at arginine residues, perhaps related to biased usage of CpG containing codons within actin genes. We also found some of the same heterozygous mutations that we observed as apparent de novo mutations in MMIHS segregating in families with intestinal pseudo-obstruction, suggesting that ACTG2 is responsible for a spectrum of smooth muscle disease. ACTG2 encodes γ2 enteric actin and is the first gene to be clearly associated with MMIHS, suggesting an important role for contractile proteins in enteric smooth muscle disease.

Author Summary

In 1976, a radiologist, Walter Berdon described a group of patients with a rare intestinal and bladder disorder in which the smooth muscle of those organs failed to contract. These patients are unable to digest food, require multiple abdominal surgeries and are diagnosed with megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS). Since the description of MMIHS, the genes that cause it have remained a mystery. We followed and obtained DNA from patients with this disorder over a period of over 14 years and assembled a large group of cases. We used whole-exome sequencing, a powerful tool used to identify disease genes, and found mutations in ACTG2, a visceral actin gene. Actins are components of muscle contractile units, and one Finnish family has been previously found with less severe gastrointestinal problems due to mutations in this gene. In our patients, we find de novo mutations in the majority of cases of MMIHS. However, we also find families with the disease over several generations due to these same mutations. This work provides the first disease gene for MMIHS, and suggests new treatment options.

Introduction

Berdon first described patients with a severe phenotype characterized by smooth muscle functional failure in 1976, at a time when total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was becoming common clinical practice [1]. Berdon noted that because the functional intestinal defect could not be corrected, finding the cause of the disorder described as megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS, OMIM 249210) would be necessary to avoid keeping patients with the disorder as “prisoners” of TPN without otherwise effective treatments. For thirty years, genetic, pathologic, endocrine, and physiologic studies have sought to determine the cause of MMIHS without success, and the clinical history of patients with these disorders often fulfills Berdon's prediction as patients remain on long-term TPN, and the underlying etiology remains unknown.

Clinically, MMIHS is characterized by prenatal bladder enlargement, neonatal functional gastrointestinal obstruction, and chronic dependence on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and urinary catheterization [2]–[4]. Patients undergo repeated abdominal surgeries, suffer hepatic complications from TPN, and are susceptible to poor nutrition, as well as infectious complications of ileostomies and intravenous and urinary catheters. The first challenge in understanding the genetics of MMIHS has been in characterizing the clinical phenotype. MMIHS is part of a phenotypic spectrum that includes intestinal pseudo-obstruction [5] (OMIM 155310, 609629), hollow visceral myopathy [6], [7] (OMIM 609629), pseudo-Hirschsprung disease [8], and irritable bowel syndrome [9]. Functional gastrointestinal obstruction is also frequently observed associated with other abnormalities such as prune-belly syndrome (OMIM 100100), external ophthalmoplegia (OMIM 277320), and Barrett esophagus (OMIM 611376). However, there is uncertainty about the extent to which locus heterogeneity and variation in expression underlie this clinical variability [9]. In addition, a number of single case reports have proposed an association of MMIHS with other disorders such as trisomy 18 [10], cardiac rhabdomyomas [11], and deletion of 15q11.2 [12]. However, in these cases it is unclear whether these genetic disorders are related to MMIHS or are coincidental findings. Autosomal recessive inheritance of MMIHS (OMIM 249210) has been suggested in numerous cases based on the presence of two affected siblings [3], [13], [14], consanguinity [15] or both [16]–[19], but no genes have been identified to date, although in retrospect a report of a dominant mutation in the ACTG2 enteric actin gene in a Finnish family with adult onset visceral myopathy has proved to be relevant [20].

Pathologic studies of intestine in MMIHS have similarly been inconclusive [4]. Some studies demonstrate abnormalities of the circular and longitudinal layers of the muscularis propria [21], [22], while others focus on abnormalities of ganglion cells, including reduced [4], increased [4], hypertrophic [23], immature, or dysplastic ganglia [4], [19]. An imbalance between intestinal hormones in cases of MMIHS has also been noted [24]. Finally, the intrinsic pacemaker cells of the gastrointestinal tract, the interstitial cells of Cajal, were noted to display abnormalities in MMIHS [25], [26]. Given this broad range of findings, there has been controversy over which pathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract are primary versus secondary [4].

Additional insight into the genetic basis of MMIHS appeared to come from a mouse model of the disease. Mice lacking expression of the α3 subunit of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor encoded by the Chrna3 gene and mice lacking both the β2 and β4 subunits encoded by the Chrnb2 and Chrnb4 genes, respectively, displayed megacystis, failure of bladder strips to contract in response to nicotine, widely dilated ocular pupils, growth failure, and perinatal mortality [27], [28]. These subunits are expressed in various sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia, and lack of transmission at these ganglia could explain the lack of contraction of involuntary smooth muscle. A role for the α3 subunit was further suggested when reduced mRNA levels were measured by in situ hybridization, and reduced immunostaining for protein was possibly found in tissues from MMIHS patients [29]. However, antibodies against the neuronal nicotinic receptor subunits are notoriously unreliable [30] and a specific search for mutations in CHRNA3 and CHRNB4 in many of the patients studied herein did not identify any potential disease-causing mutations [31].

Results

Whole-Exome Sequencing in an MMIHS Cohort

Since the findings in mice harboring mutations in Chrna3 or in Chrnb2 and Chrnb4 combined caused MMIHS-like phenotypes, we have conducted a study of MMIHS aimed at identifying the genetic cause. We collected samples from patients with MMIHS and related phenotypes, some of whom have been previously reported [31]. Our cohort of 34 families to date includes 27 DNA samples from probands including individuals diagnosed with MMIHS (20 probands) as well as intestinal pseudo-obstruction (4 probands), prune belly syndrome (2 probands), and hollow visceral myopathy (1 proband). Examples of radiologic findings are shown in Figure 1. Study recruitment has taken place over a period of 14 years.

Figure 1. Radiologic features of MMIHS due to de novo ACTG2 mutations.

A.) An infant subject from our cohort (Fam28-1) underwent an upper GI study with small bowel follow-through. Contrast was administered beyond the pylorus (left panel, arrow) in this patient who had undergone a previous Ladd procedure. At two hours, the contrast has mostly passed retrograde back into the stomach (arrow) contrary to expectations. At six hours, the contrast is in the small intestine (arrow) and has not reached the colon. At two days, contrast material is still present in the colon (arrow) suggesting a severely delayed transit of material in the GI tract consistent with hypoperistalsis. No physical obstructive lesions are visualized. B.) An abdominal CT scan on an adolescent patient with MMIHS (Fam26-1). The patient has a diverting ileostomy, but multiple distended bowel loops with air-fluid levels (arrows) are seen at the level of the sacrum (left) and lumbar spine (right). C.) A voiding cystourethrogram on an infant male subject (Fam29-1) showing a grossly distended bladder.

We undertook whole-exome sequencing in 11 unrelated probands. The exome sequencing characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 11 probands, eight were diagnosed with MMIHS and three diagnosed with intestinal pseudo-obstruction. We identified heterozygous missense variants in the ACTG2 gene encoding γ2 enteric actin in six of the 11 individuals. We reasoned that ACTG2 was an excellent candidate for MMIHS as a thin filament protein in the sarcomere involved in muscular contraction. We therefore undertook Sanger sequencing of all the exons and intron-exon boundaries of ACTG2 in 16 additional probands in our cohort.

Table 1. Exome analysis summary for six probands with MMIHS due to ACTG2 mutations.

| Subject | Total # unfiltered variants | Average Coverage | % at 10× coverage | % at 20× coverage | %at 40× coverage |

| Fam4-1 | 129,171 | 118 | 95.1 | 93.3 | 86.0 |

| Fam19-4 | 122,121 | 80 | 93.1 | 89.4 | 75.2 |

| Fam25-1 | 146,726 | 112 | 94.1 | 91.9 | 84.1 |

| Fam28-1 | 131,113 | 132 | 92.5 | 89.5 | 81.9 |

| Fam29-1 | 132,740 | 140 | 92.9 | 90.2 | 83.2 |

| Fam30-1 | 127,370 | 135 | 93.0 | 90.3 | 83.1 |

De Novo and Inherited ACTG2 Mutations in the MMIHS Cohort

The results for all the heterozygous ACTG2 variants in our cohort are summarized in Table 2. All of these variants were unique to our cohort, as none of the ACTG2 variants found in our patients, were present neither within the 1000 Genomes project data (http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html) nor within the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/). In addition, within our internal data, excluding the cases presented here, none of these variants were found in approximately 1900 other samples analyzed by the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (http://www.mendelian.org/) nor within 1200 clinical samples analyzed in the BCM clinical laboratory. We did identify a number of other novel heterozygous variants, but these were all distinct from the variants seen in our MMIHS cohort (Table S1). Within our group, 15 probands had mutations in ACTG2 in comparison to 12 probands in the cohort without mutations in ACTG2. Of note, we observed ten apparently de novo events (Figure 2). We observed 6 novel C>T transition mutations at CpG dinucleotides affecting arginine amino acid residues including a recurrent mutation (c.769C>T; p.R257C) seen in 3 de novo cases (Fam4-1, Fam30-1, Fam25-1).

Table 2. Characteristics of the ACTG2 mutations in the MMIHS cohort.

| Subject | Position (hg19) Chr2 | cDNA changea | Amino-acid changec | CpG | Inheritance | Individuals with variant out of 1900d |

| Fam4-1 | 74141962 | c.769C>T | p.R257C | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam11-1 | 74140693 | c.533G>A | p.R178H | + | Maternal | 0 |

| Fam12-1 | 74128450 | c.119G>A | p.R40H | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam13-1 | 74141962 | c.769C>T | p.R257C | + | Maternal | 0 |

| Fam14-1 | 74129494 | c.134T>C | p.M45T | − | De novo | 0 |

| Fam16-1 | 74136215 | c.412T>A | p.Y134N | − | De novo | 0 |

| Fam17-1 | 74129547 | c.187C>G | p.R63G | + | Unknown | 0 |

| Fam19-4 | 74129825 | c.330C>Ab | p.F110L | − | Unknown | 0 |

| Fam25-1 | 74141962 | c.769C>T | p.R257C | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam26-1 | 74128449 | c.118C>T | p.R40C | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam28-1 | 74140753 | c.593G>A | p.G198D | − | De novo | 0 |

| Fam29-1 | 74140692 | c.532C>T | p.R178C | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam30-1 | 74141962 | c.769C>T | p.R257C | + | De novo | 0 |

| Fam34-1 | 74128450 | c.119G>A | p.R40H | + | Paternal | 0 |

| Fam35-1 | 74140693 | c.533G>A | p.R178H | + | De novo | 0 |

Deduced cDNA change in transcript NM_001615 unless otherwise indicated.

Transcript Uc010fex.1.

Deduced amino acid substitution.

Presence of the observed mutation in other exomes from the Baylor Center for Mendelian Genomics cohort.

Figure 2. Clinical features and inheritance of ACTG2 mutations in de novo and familial cases.

Family pedigrees with clinical features correlated with the severity of smooth muscle dysfunction are shown. The most severe features of TPN dependence and megacystic bladder noted as dark squares within the upper quarters. The diagnosis of MMIHS (orange) was made in all but one subject with de novo ACTG2 mutations. One subject (Fam 12-1) was diagnosed with gastrointestinal hollow visceral myopathy but had megacystis prenatally. Three families exhibiting dominant inheritance patterns are depicted below. One subject (Fam 13-1) suffered from a megacystic bladder but had later onset functional GI pseudo-obstruction. Another family (Fam19) is shown with two affected siblings with functional GI obstruction. Both carry a nonsynonymous mutation in alternate exon 4 of a predicted short ACTG2 isoform (Uc010fex.1 indicated by *). Another family exhibited more extensive dominant inheritance (Fam34) consistent with familial visceral myopathy. Multiple paternal relatives suffer from episodes of gastrointestinal obstruction, constipation, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and bladder dysmotility segregating with the same mutation.

Clinical Characteristics of Smooth Muscle Disease Due to De Novo ACTG2 Mutations

The clinical characteristics of the patients with apparent de novo mutations are summarized in Table 3 and in Text S1. The age at the time of follow-up was from less than one year to 25 years. In the ten apparently de novo cases, seven patients were diagnosed with megacystis prenatally, and two of these underwent fetal surgery. The three individuals without megacystis were nonetheless dependent on catheterization of the bladder long-term. Prune-belly syndrome was observed in one of the cases (Fam16-1).

Table 3. Clinical characteristics of the patients with MMIHS due to ACTG2 de novo mutations.

| Subject | Fam4-1 | Fam12-1 | Fam14-1 | Fam16-1 | Fam25-1 | Fam26-1 | Fam28-1 | Fam29-1 | Fam30-1 | Fam35-1 |

| ACTG2 Mutation | p.R257C | p.R40H | p.M45T | p.Y133N | p.R257C | p.R40C | p.G198D | p.R178C | p.R257C | p.R178H |

| Gender | M | M | F | M | M | F | F | M | F | F |

| Age in years | 11 | 16 | 18 | 25 | 13 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Paternal age at birth | 28 | 37 | 39 | 28 | 44 | 36 | 32 | 26 | 24 | 32 |

| Maternal age at birth | 31 | 33 | 35 | 26 | 36 | 33 | 31 | 32 | 26 | 28 |

| Megacystis | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Fetal bladder diversion | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Neonatal bilious emesis | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Abdominal surgery/malrotation | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Microcolon | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Lifetime TPN dependence | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lifetime bladder catheterization | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Motility treatment*(response) | M (−) Cis(−) | Cis (+) | Cis (+) | Cis (+) | Cis (−) | M (−)E (−) | ||||

| Other medical conditions | Non-febrile seizures age 3 y | ADHD since age 6 y | Asthma, pectus excavatum, prune belly. cardio-myopathy | ADHD | Undescended testicle |

+ Feature present, − Feature absent,

*M- Metaclopramide, Cis- Cisapride, E-Erythromycin, (+) responsive, (−) non-responsive.

The gastrointestinal manifestations were similarly severe. Of the ten apparent de novo cases, seven had bilious vomiting as a neonate, and eight were diagnosed with intestinal malrotation. All ten patients had multiple abdominal surgeries (Table 4). Long-term dependence on TPN was a consistent feature, but did not extend throughout life for all the patients. Two patients had very intermittent TPN requirements, usually during surgical recovery. Another patient (Fam26-1) had an interval of improvement at age four years followed by reinitiation of TPN at six years.

Table 4. Natural history of patients with MMIHS due to ACTG2 de novo mutations.

| Subject | Fam4-1 | Fam12-1 | Fam14-1 | Fam16-1 | Fam25-1 | Fam26-1 | Fam28-1 | Fam29-1 | Fam30-1 | Fam35-1 |

| Mutation | p.R257C | p.R40H | p.M45T | p.Y133N | p.R257C | p.R40C | p.G198D | p.R178C | p.R257C | p.R178H |

| Surgeries/age | Vesicostomy/neonate | Hernia repair/neonate | Ladd surgery/neonate | Vesicostomy/neonate | Jejun-ostomy, ileostomy/1 y | Vesicostomy/neonate | Ladd surgery/neonate | Removal of bladder shunt/neonate | Small bowel ostomy/<1 y | Ladd surgery/neonate |

| Malrotation/3 months | Ileostomy/1 y | Colon/ileum resection ileostomy/9 y | Ileostomy and colectomy/3 months | Ileostomy revision/1 y | Ileostomy/9 y | Rectal biopsy/neonate | Ileostomy/<1 y | Rectal biopsy/<1 y | ||

| Appendectomy/chole-cystectomy/3 months | Ileostomy revision/2 y | Hemi-gast-rectomy removal of pylorus/10 y | Pectus surgery, abdominal wall recon-struction/adolescent | Multi-visceral transplant/3 y | Colectomy/16 y | Lysis of adhesions/2 months | ||||

| Functional study | Manometry with absent peristalsis | Manometry with absent peristalsis | Manometry with absent peristalsis | Small bowel follow-through with delayed emptying | Manometry with absent peristalsis | |||||

| Outcome | Death at 11 years from multiple bouts of pancreatitis | Ileostomy, catheter dependent cognitively normal | IV fluids and food, self-voiding, cognitively normal | Eating by mouth, urostomy, ileostomy, hypothyroid | Intestinal transplant, ileostomy, clinically well | Frequent infections listed for multi-visceral transplant | Partial parenteral nutrition, catheter dependent | TPN and catheter dependent, cognitively normal | TPN dependent, cognitively normal | TPN dependent, cognitively normal |

Interestingly, of the ten apparent de novo patients, three reported partial but significant clinical improvement on cisapride, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist and gastroprokinetic agent (see Text S1). Recently this drug was removed from the market for cardiac side effects, but one patient continued on the drug as an FDA-approved case of compassionate use, and the two others indicated strong desires to remain on the drug despite the risks. Two other families found that the same drug did not have a significant effect.

Clinical outcomes in our cohort differ from the 19.7% survival rate reported in the literature [2]. Of the ten apparent de novo cases, nine were alive at the time of last follow-up; while one individual died at age 11 after multiple episodes of pancreatitis. One individual had undergone an intestinal transplant, and one individual was wait-listed for combined intestinal and liver transplant. Of the nine surviving individuals, eight had ileostomies. The oldest survivor amongst the apparent de novo cases was 25 years old, while the oldest previously reported case of MMIHS was 24 years [2]. While this suggests improved survival in our cohort, we observed frequent abdominal surgery, and dependence on TPN and chronic catheterization, suggesting that improvements in supportive care over time rather than a milder phenotype associated with ACTG2 mutations are responsible for this improved survival.

Familial Disease Due to ACTG2 Mutations

In addition to these apparent de novo cases, five other probands were heterozygous for ACTG2 variants; in three of these cases the mutation was inherited from one of the parents. In one case the inheritance remains unknown as parental samples are not available. In an additional family (Fam19), the proband and an affected sibling both carry a heterozygous mutation that affects an alternate exon 4 (c.330C>A; p.F110L) of a predicted ACTG2 short isoform. The proband (Fam19-1) had multiple abdominal surgeries for obstruction and long-standing hypomotility. She has been on TPN intermittently since age 17 years, but has not required bladder catheterization. The sibling (Fam19-4) suffered years of intestinal symptoms and underwent an endoscopy suggesting gastroparesis. However she had not had any abdominal surgery. No parental clinical information was available. The mother does not carry this mutation, and a paternal sample is not available. The data from this family suggests but perhaps do not prove entirely that the alternative exon 4 which would result in a very short protein isoform is functionally important.

In all three inherited cases, we observed mutations identical to those identified in the apparent de novo cases (c.119G>A; p.R40H, c.533G>A; p.R178H and c.769C>T; p.R257C). The clinical findings in the familial cases and in the affected parents were notable for milder disease, more frequently classified as intestinal pseudo-obstruction. In one family (Fam34), the proband inherited the mutation (c.119G>A; p.R40H) from the father, who had no history of megacystis or neonatal abdominal surgery but had two abdominal surgeries in adulthood for episodes of gastrointestinal obstruction. Multiple paternal relatives over four generations carried the same mutation and were noted to have bowel and bladder dysfunction segregating as an autosomal dominant mutation (Figure 2).

In another family, the proband (Fam 13-1) inherited the mutation (c.769C>T; p.R257C) from the mother (Figure 2). The proband had prenatal megacystis but had a period of normal bowel and bladder function in the first years of life. She eventually experienced progressive pseudo-obstruction and ultimately died at age 13 years. Medical records were not available for her mother, but a history of gastrointestinal disease and a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome were reported.

Predicted Functional Effect of the ACTG2 Mutations

The mutations we observed extended from exon 2 to exon 7 of the transcript (Figure 3A). Alignment of all six human actin proteins, which are highly conserved, revealed identity among all the amino acids in which we observed substitutions. All of these genes are implicated in human disease. De novo missense mutations in ACTB and ACTG1 underlie the brain malformation syndrome Baraitser-Winter (OMIM 243310) [32], [33]. Mutations in ACTC1 are implicated in a range of cardiac phenotypes including cardiomyopathy (OMIM 613424) [34], cases of nemaline myopathy (OMIM 161800) are due to mutations in ACTA1 which can be dominantly or recessively inherited depending on the mutation [35], and ACTA2 mutations are associated with incompletely penetrant dominantly inherited aneurysm and dissections (OMIM 611788). We compared the ACTG2 mutations in our cohort to mutations from these disorders in the identical amino acid position along the actin filament (Figure 3B). There was clearly alignment between multiple mutations observed in our cohort and those implicated in Baraitser-Winter, nemaline myopathy, and thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections.

Figure 3. ACTG2 mutations affect conserved residues that are also targets for Mendelian disease.

A.) Depiction of the mutations on the exons of the gene. Introns are not shown to scale. The mutations associated with MMIHS and intestinal pseudo-obstruction (orange) and those associated with intestinal pseudo-obstruction (green), including the previously reported mutation in one Finnish family are shown. A nonsense allele at position R63 was identified in our exome database associated with no clinical phenotype. The black, red, and blue lines under specific mutations highlight areas of multi-sequence alignment in boxes of corresponding colors in B. B.) Comparison of the mutations in MMIHS/intestinal pseudo-obstruction with disease causing mutations in other actin genes.

We also explored the question of the phenotypic consequences of haploinsufficiency at ACTG2. We identified an incidental nonsense mutation (c.C187T:p.R63X) in ACTG2 in our internal exome sequencing database from a group of approximately 1900 individuals in the Center for Mendelian Genomics at Baylor College of Medicine (Table S1). The individual was an unaffected parent from a study of an unrelated disorder. This individual reported mild intermittent constipation, not requiring medications, and no history of abdominal surgery, or bladder dysfunction. In aggregate, these data suggest that ACTG2 haploinsufficiency is not clinically significant, although a mild phenotype with incomplete penetrance cannot be excluded. For all of the genotype-phenotype relationships shown in Figure 3B, virtually all of the reported mutations are missense with very few or no examples of frameshift or nonsense mutations. One reason for this bias might be that heterozygous loss-of-function mutations are benign or cause a different phenotype for these actin loci.

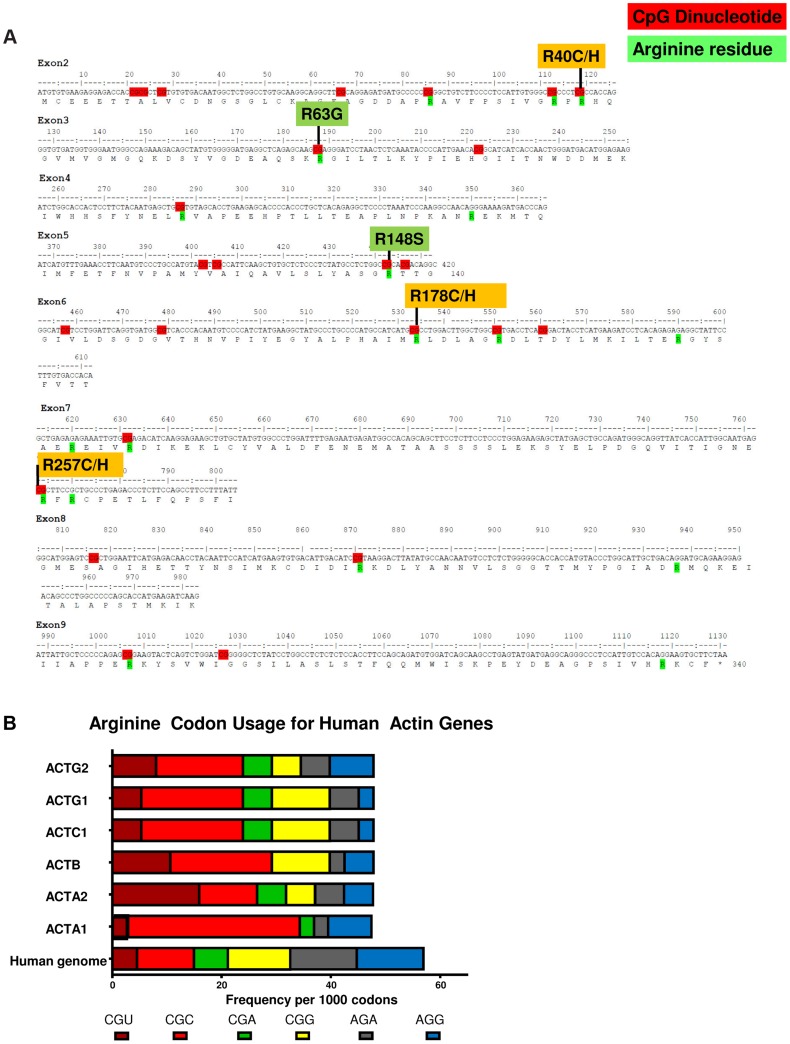

CpG Dinucleotides in ACTG2 and Paternal Age

Out of the 10 variants in ACTG2 identified in 14 unrelated probands, six result from C>T transitions at CpG dinucleotides altering an arginine codon (Figure 4A). We observed that the CGC codon encodes 33% of the arginine residues in the γ-actin protein compared to 18% of arginine residues genome wide (Figure 4B) [36]. One explanation for the pattern of codon usage could relate to the expression of actin genes, as more highly expressed genes have been observed to have significantly skewed codon usage [37]. Given the presence of multiple CpG dinucleotides due to this pattern of codon usage, we surveyed paternal age in our de novo cases. We observed an average paternal age of 32.7 years amongst the families with de novo mutations with a standard deviation of 6.7 years which is not sufficient to conclude statistically whether these ten apparently de novo mutations may be associated with advanced paternal age.

Figure 4. CpG dinucleotides within arginine codons are targets of de novo events in MMIHS.

A.) The coding exons are shown with translation for the ACTG2 gene. CpG dinucleotides are highlighted in red. Arginine residues in the protein are highlighted in green, and the mutations associated with ACTG2 smooth muscle disease are aligned above the sequence. B.) The frequency of codon usage per 1000 codons for 6 arginine codons is shown. The human genome as a whole (bottom bar) is compared to all human actin genes including ACTG2.

Discussion

Identification of ACTG2 mutations underlying a significant proportion of MMIHS and intestinal pseudo-obstruction has significance for three major reasons. First, autosomal dominant rather than autosomal recessive mutations now are known to be present in the majority of families (15 of 26 probands reported in this study). Many cases in the literature as well as the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database suggest autosomal recessive inheritance. While other loci exhibiting recessive inheritance are possible, nearly half of our cases of MMIHS appear to follow a dominant or sporadic pattern of inheritance with heterozygous mutations segregating with the phenotype.

Second, the phenotypic spectrum for disease causing mutations in ACTG2 can now be relatively well defined. All of the apparent de novo cases had clear indications of severe smooth muscle disease with prenatal or neonatal onset, urinary catheterization, and dependence on TPN. However, phenotypic variability and distinct complications existed such that prune belly syndrome, MMIHS, hollow visceral myopathy, and intestinal pseudo-obstruction were all diagnosed. Reorganizing these clinical entities into a spectrum of ACTG2 related disorders will be of great benefit in understanding the natural course of these diseases.

Third, a better understanding of the pathophysiology could lead to treatment opportunities. It was notable that three individuals reported here with MMIHS due to apparent de novo mutations in ACTG2 reported clinical improvement on cisapride, a serotonergic 5HT4 agonist. Serotonergic activity at the 5HT4 receptor has been noted to be a therapeutic target for constipation and irritable bowel syndrome [38]. Cisapride was proposed as a therapy for MMIHS in 1991 [14]. Subsequent case reports have noted failure of cisapride to produce clinical improvement in MMIHS [39], [40]. However in our cohort three patients out of five who had been prescribed cisapride reported improved motility by subjective clinical improvement. Two of the three patients were taken off this drug for cardiac side effects. Given that new 5HT4 agonist agents with safer cardiac profiles are under study [41], patients with ACTG2 mutations may be candidates for this therapeutic strategy. Also, the mutational data suggest the feasibility of selective knock-down of the mutant transcript using antisense oligonucleotides, offering some therapeutic hope to affected individuals and families [42].

Finally our study effectively refocuses the study of MMIHS back to the contractile apparatus of the smooth muscle in an analogous way to how cardiomyopathy and myopathy tie to muscle contractile genes. Mendelian disorders of skeletal and cardiac muscle function have historically underscored the essential role of the sarcomere and its contractile apparatus in human health and disease [43], [44]. Since Huxley formulated the sliding filament model, all muscle contraction has been understood as a product of the interaction of two polymers, the thin filament actins and thick filament myosins [45]. Mendelian disorders largely conform to Huxley's fundamental insight as numerous disorders are now attributed to mutations in actins, myosins, and related proteins [46], [47]. Sarcomere proteins had not been previously explored in MMIHS perhaps because the role of sarcomeric proteins in smooth muscle disease is less clear than in skeletal and cardiac disorders, and smooth muscle lacks the rigid alignment of the sarcomeres seen in cardiac and skeletal muscle. However, vascular smooth muscle disease has also been attributed to mutations in actin and myosin genes with the discovery of mutations in ACTA2 [48] and MYH11 [49] in thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. There are also reports of a specific mutation in ACTA2 associated with vascular aneurysms and hypomotility of the gastrointestinal tract (OMIM 613834) [50] and also with prune belly sequence [51]. Additionally, as mentioned above, adult onset visceral myopathy was recently associated with a dominant mutation in the ACTG2 enteric actin gene in a Finnish family [20]. These findings provide the context for our data demonstrating a role for ACTG2 in MMIHS. While the mouse model for CHRNA3 generated promising insight into ganglion cell neurotransmission and smooth muscle function [27], the smooth muscle itself is clearly also involved in MMIHS. These results strongly suggest that there are other genes that are mutated in MMIHS, and candidate genes can be envisioned based on the combined data from mouse and human mutations. MMIHS can be considered the most severe Mendelian enteric smooth muscle myopathy.

After the submission of this manuscript, a report was published detailing the identification of de novo ACTG2 mutations by exome sequencing in two children with MMIHS [52].

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects and Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained prior to participation from all subjects or parents of recruited subjects under one of two Institutional Review Board approved protocols at Baylor College of Medicine.

Clinical Evaluation

Whenever possible, our clinicians assessed study subjects by direct history, physical examination, and family history analysis. In some cases, clinicians referred subjects from centers around the world, and in those cases clinical information in the form of chart records and notes from the referring physicians were reviewed. Interviews with these subjects were also conducted by telephone. Families were asked prenatal history, and dates and nature of abdominal surgeries. Whenever available, reports from prenatal ultrasound, operative reports, manometry, or radiologic studies were reviewed.

Whole-Exome Capture and Sequencing

Methods utilized for whole-exome sequencing have been previously described in detail [53]. In summary, 1 µg of genomic DNA was fragmented by sonication in a Covaris plate (Covaris, Inc. Woburn, MA). Genomic DNA samples were constructed into Illumina paired-end libraries as described [53]. Pre-capture libraries were pooled together and hybridized in solution to the BCM-HGSC CORE exome capture design [54] (52 Mb, NimbleGen). Captured DNA fragments were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform producing 9–10 Gb per sample and achieving an average of 90% of the targeted exome bases covered to an minimal depth of 20× or greater.

Data Analysis

Produced sequence reads were mapped and aligned to the GRCh37 (hg19) human genome reference assembly using the HGSC Mercury analysis pipeline (http://www.tinyurl.com/HGSC-Mercury/). Variants were determined and called using the Atlas2 [55] suite to produce a variant call file (VCF) [56]. High-quality variants were annotated using an in-house developed suite of annotation tools [57].

Sanger Sequencing

Primers were designed to encompass all the exons and intron-exon boundaries of the ACTG2 gene using ExonPrimer (Tim Strom, http://ihg.gsf.de/ihg/ExonPrimer.html) and Primer3 [58]. Sanger reads were analyzed using LASERGENE Seqman software [59].

Alignments and Analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were performed using Clustal Omega [60] and depicted using Boxshade. Arginine codon usage was determined using the Codon Usage Database and the countcodon program of Yazukazu Nakamura.

Supporting Information

Novel variants in the ACTG2 gene within the Center for Mendelian Genomics data excluding the MMIHS cohort.

(DOCX)

Clinical Case histories for cases of MMIHS due to ACTG2 mutations. A clinical narrative from birth to present is provided for each of the patients with the nature of the ACTG2 mutation.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors with to thank the families involved in this study for participation. We also thank Karen Schulze for a critical reading of the manuscript, and Wojciech Wiszniewski for advice in its prepartion.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant R01 NS058529 to JRL and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Baylor Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics grant U54 HG006542. MFW received funding from the NINDS (NS076547), and the Simmons Family Foundation. FJP holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists (CAMS) from the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Berdon WE, Baker DH, Blanc WA, Gay B, Santulli TV, et al. (1976) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: a new cause of intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Report of radiologic findings in five newborn girls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 126: 957–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gosemann JH, Puri P (2011) Megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: systematic review of outcome. Pediatr Surg Int 27: 1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kohler M, Pease PW, Upadhyay V (2004) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS) in siblings: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg 14: 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puri P, Shinkai M (2005) Megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Semin Pediatr Surg 14: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuler H, Nyakern M, Schutt CE, Lindberg U, Karlsson R (2000) Mutational analysis of arginine 177 in the nucleotide binding site of beta-actin. Eur J Biochem 267: 4054–4062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arslan M, Bayraktar Y, Oksuzoglu G, Ozdemir A, Sokmensuer C, et al. (1999) Four cases with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to hollow visceral myopathy. Hepatogastroenterology 46: 349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higman D, Peters P, Stewart M (1992) Familial hollow visceral myopathy with varying urological manifestations. Br J Urol 70: 435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toyosaka A, Okamoto E, Okasora T, Nose K, Tomimoto Y (1993) Clinical, laboratory and prognostic features of congenital large intestinal motor dysfunction (pseudo-Hirschsprung's disease). Clin Auton Res 3: 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Puri P, Gosemann JH (2012) Variants of Hirschsprung disease. Semin Pediatr Surg 21: 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chamyan G, Debich-Spicer D, Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness E (2001) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome and aganglionosis in trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet 102: 293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Couper RT, Byard RW, Cutz E, Stringer DA, Durie PR (1991) Cardiac rhabdomyomata and megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. J Med Genet 28: 274–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szigeti R, Chumpitazi BP, Finegold MJ, Ranganathan S, Craigen WJ, et al. (2010) Absent smooth muscle actin immunoreactivity of the small bowel muscularis propria circular layer in association with chromosome 15q11 deletion in megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol 13: 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farrell SA (1988) Intrauterine death in megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. J Med Genet 25: 350–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anneren G, Meurling S, Olsen L (1991) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS), an autosomal recessive disorder: clinical reports and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet 41: 251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Narayanan M, Murphy MS, Ainsworth JR, Arul GS (2007) Mydriasis in association with MMIHS in a female infant: evidence for involvement of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Pediatr Surg 42: 1288–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garber A, Shohat M, Sarti D (1990) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome in two male siblings. Prenat Diagn 10: 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winter RM, Knowles SA (1986) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: confirmation of autosomal recessive inheritance. J Med Genet 23: 360–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McNamara HM, Onwude JL, Thornton JG (1994) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: a case report supporting autosomal recessive inheritance. Prenat Diagn 14: 153–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kirtane J, Talwalker V, Dastur DK (1984) Megacystis, microcolon, intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: possible pathogenesis. J Pediatr Surg 19: 206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lehtonen HJ, Sipponen T, Tojkander S, Karikoski R, Jarvinen H, et al. (2012) Segregation of a missense variant in enteric smooth muscle actin gamma-2 with autosomal dominant familial visceral myopathy. Gastroenterology 143: 1482–1491 e1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Puri P, Lake BD, Gorman F, O'Donnell B, Nixon HH (1983) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: a visceral myopathy. J Pediatr Surg 18: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rolle U, O'Briain S, Pearl RH, Puri P (2002) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: evidence of intestinal myopathy. Pediatr Surg Int 18: 2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piotrowska AP, Rolle U, Chertin B, De Caluwe D, Bianchi A, et al. (2003) Alterations in smooth muscle contractile and cytoskeleton proteins and interstitial cells of Cajal in megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 38: 749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taguchi T, Ikeda K, Shono T, Goto S, Kubota M, et al. (1989) Autonomic innervation of the intestine from a baby with megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: I. Immunohistochemical study. J Pediatr Surg 24: 1264–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piaseczna Piotrowska A, Rolle U, Solari V, Puri P (2004) Interstitial cells of Cajal in the human normal urinary bladder and in the bladder of patients with megacystis-microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. BJU Int 94: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rolle U, Piaseczna-Piotrowska A, Puri P (2007) Interstitial cells of Cajal in the normal gut and in intestinal motility disorders of childhood. Pediatr Surg Int 23: 1139–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu W, Gelber S, Orr-Urtreger A, Armstrong D, Lewis RA, et al. (1999) Megacystis, mydriasis, and ion channel defect in mice lacking the alpha3 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 5746–5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu W, Orr-Urtreger A, Nigro F, Gelber S, Sutcliffe CB, et al. (1999) Multiorgan autonomic dysfunction in mice lacking the beta2 and the beta4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 19: 9298–9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richardson CE, Morgan JM, Jasani B, Green JT, Rhodes J, et al. (2001) Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome and the absence of the alpha3 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. Gastroenterology 121: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moser N, Mechawar N, Jones I, Gochberg-Sarver A, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. (2007) Evaluating the suitability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies for standard immunodetection procedures. J Neurochem 102: 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lev-Lehman E, Bercovich D, Xu W, Stockton DW, Beaudet AL (2001) Characterization of the human beta4 nAChR gene and polymorphisms in CHRNA3 and CHRNB4. J Hum Genet 46: 362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riviere JB, van Bon BW, Hoischen A, Kholmanskikh SS, O'Roak BJ, et al. (2012) De novo mutations in the actin genes ACTB and ACTG1 cause Baraitser-Winter syndrome. Nat Genet 44: 440–444, S441–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di Donato N, Rump A, Koenig R, Der Kaloustian VM, Halal F, et al. (2013) Severe forms of Baraitser-Winter syndrome are caused by ACTB mutations rather than ACTG1 mutations. Eur J Hum Genet 22 ((2)) 179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muller M, Mazur AJ, Behrmann E, Diensthuber RP, Radke MB, et al. (2012) Functional characterization of the human alpha-cardiac actin mutations Y166C and M305L involved in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 3457–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laing NG, Wilton SD, Akkari PA, Dorosz S, Boundy K, et al. (1995) A mutation in the alpha tropomyosin gene TPM3 associated with autosomal dominant nemaline myopathy. Nat Genet 9: 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakamura Y, Gojobori T, Ikemura T (2000) Codon usage tabulated from international DNA sequence databases: status for the year 2000. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Plotkin JB, Kudla G (2011) Synonymous but not the same: the causes and consequences of codon bias. Nat Rev Genet 12: 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fayyaz M, Lackner JM (2008) Serotonin receptor modulators in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag 4: 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hiradfar M, Shojaeian R, Dehghanian P, Hajian S (2013) Megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. BMJ Case Rep doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Giuliani S, Vendryes C, Malhotra A, Shaul DB, Anselmo DM (2010) Prune belly syndrome associated with cloacal anomaly, patent urachal remnant, and omphalocele in a female infant. J Pediatr Surg 45: e39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Manabe N, Wong BS, Camilleri M (2010) New-generation 5-HT4 receptor agonists: potential for treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 19: 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carroll JB, Warby SC, Southwell AL, Doty CN, Greenlee S, et al. (2011) Potent and selective antisense oligonucleotides targeting single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Huntington disease gene/allele-specific silencing of mutant huntingtin. Mol Ther 19: 2178–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ashrafian H, McKenna WJ, Watkins H (2011) Disease pathways and novel therapeutic targets in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 109: 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sparrow JC, Nowak KJ, Durling HJ, Beggs AH, Wallgren-Pettersson C, et al. (2003) Muscle disease caused by mutations in the skeletal muscle alpha-actin gene (ACTA1). Neuromuscul Disord 13: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weber A, Franzini-Armstrong C (2002) Hugh E. Huxley: birth of the filament sliding model of muscle contraction. Trends Cell Biol 12: 243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seidman CE, Seidman JG (2011) Identifying sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a personal history. Circ Res 108: 743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rahimov F, Kunkel LM (2013) The cell biology of disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol 201: 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guo DC, Pannu H, Tran-Fadulu V, Papke CL, Yu RK, et al. (2007) Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Nat Genet 39: 1488–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhu L, Vranckx R, Khau Van Kien P, Lalande A, Boisset N, et al. (2006) Mutations in myosin heavy chain 11 cause a syndrome associating thoracic aortic aneurysm/aortic dissection and patent ductus arteriosus. Nat Genet 38: 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Milewicz DM, Ostergaard JR, Ala-Kokko LM, Khan N, Grange DK, et al. (2010) De novo ACTA2 mutation causes a novel syndrome of multisystemic smooth muscle dysfunction. Am J Med Genet A 152A: 2437–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Richer J, Milewicz DM, Gow R, de Nanassy J, Maharajh G, et al. (2012) R179H mutation in ACTA2 expanding the phenotype to include prune-belly sequence and skin manifestations. Am J Med Genet A 158A: 664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thorson W, Diaz-Horta O, Foster J 2nd, Spiliopoulos M, Quintero R, et al. (2013) De novo ACTG2 mutations cause congenital distended bladder, microcolon, and intestinal hypoperistalsis. Hum Genet [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lupski JR, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Yang Y, Bainbridge MN, Jhangiani S, et al. (2013) Exome sequencing resolves apparent incidental findings and reveals further complexity of SH3TC2 variant alleles causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Genome Med 5: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bainbridge MN, Wang M, Wu Y, Newsham I, Muzny DM, et al. (2011) Targeted enrichment beyond the consensus coding DNA sequence exome reveals exons with higher variant densities. Genome Biol 12: R68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, Jackson AR, Paithankar S, et al. (2012) An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 13: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, et al. (2011) The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27: 2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bainbridge MN, Wiszniewski W, Murdock DR, Friedman J, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. (2011) Whole-genome sequencing for optimized patient management. Sci Transl Med 3: 87re83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, et al. (2012) Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Burland TG (2000) DNASTAR's Lasergene sequence analysis software. Methods Mol Biol 132: 71–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, Squizzato S, Park YM, et al. (2013) Analysis Tool Web Services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 41 ((Web Server issue)) W597–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Novel variants in the ACTG2 gene within the Center for Mendelian Genomics data excluding the MMIHS cohort.

(DOCX)

Clinical Case histories for cases of MMIHS due to ACTG2 mutations. A clinical narrative from birth to present is provided for each of the patients with the nature of the ACTG2 mutation.

(DOCX)