Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to further elucidate the role of the vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) disease. We hypothesized that that AAA-SMC are unique and actively participate in the process of degrading the aortic matrix.

Methods and Results

Whole-genome expression profiles of SMC from AAA, non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) were compared. We quantified elastolytic activity by culturing SMC in [3H]elastin-coated plates and measuring solubilized tritium in the media after 7 days. MMP-2 and MMP-9 production was assessed using real-time PCR, zymography and western blotting.

Each SMC type exhibited a unique gene expression pattern. AAA-SMC had greater elastolytic activity than NAA (+68%, P<0.001) and CEA-SMC (+45%, P<0.001). Zymography showed an increase of active-MMP-2 (62kD) in media from AAA-SMC. AAA-SMC demonstrated 2-fold greater expression of MMP-2 mRNA (P<0.05) and 7.3-fold greater MMP-9 expression (P<0.01) than NAA-SMC. Culture with U937 monocytes caused a synergistic increase of elastolysis by AAA-SMC (41%, P<0.001) but not NAA or CEA (P=0.99). Co-culture with U937 caused a large increase in MMP-9 mRNA in AAA and NAA-SMC (P<0.001). MMP-2 mRNA expression was not affected. Western blots of culture media showed a 4-fold increase of MMP-9 (92kD) protein only in AAA-SMC/U937 but not in NAA-SMC/U937 (P<0.001) and a large increase in active-MMP2 (62kD) which was less apparent in NAA/U937 media (P<0.01).

Conclusions

AAA-SMC have a unique gene expression profile and a pro-elastolytic phenotype that is augmented by macrophages. This may occur via a failure of post-transcriptional control of MMP-9 synthesis.

Introduction

The aortic aneurysm remains a poorly understood inflammatory, matrix-degenerative disease which results in significant morbidity and mortality. ENREF 1 ENREF 1 ENREF 1 The vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) is the principal intrinsic cell of the aortic wall and is capable of 1) matrix synthesis, 2) protease and\or protease inhibitor elaboration and 3) inflammatory cell recruitment. As such it is capable of key influence on the homeostasis of the aortic matrix. The effect of these cells on the development and growth of aortic aneurysms may be related to loss of synthetic capability due to apoptosis or other mechanisms,1,2 but there is also growing evidence that aortic VSMC have the potential to directly participate in the degenerative process.3-5 In addition, the ENREF 8 unique predilection of aneurysms for the infrarenal aorta and adjacent iliac vasculature could be related to regionalization of the intrinsic cellular components.6-10

We hypothesized that the VSMC isolated from aortas in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms would demonstrate a unique pattern of gene expression when compared to cells derived from non-dilated infrarenal aorta under identical culture conditions. We also hypothesized that this expression phenotype would manifest with increased direct and indirect elastolytic activity compared to VSMC derived from non-aneurysmal aortic wall or even pathologically altered VSMC derived from atherosclerotic plaque. In this study, we compared whole genome gene expression patterns of the explant VSMC from each of these tissues, directly measured their ability to degrade elastin, and characterized specific pathways and enzymes which are involved in this process.

Methods

Human tissues were collected with the approval and oversight of the Institutional Review Board at Washington University. Details of the methods of analysis can be found in the on-line appendix (Supplemental Methods).

Microdissection and RNA extraction

Briefly, frozen sections from abdominal aortic aneurysm specimens were microdissected using a PixCell IIe system (Arcturus). Each histologic layer of the aortic wall (intima, media and aventitia) was identified and separately dissected onto “caps” assuring no incidental attachment of adjacent tissue. Tissue from 5 serial sections was combined, and RNA extracted using the PicoPure RNA Kit (Arcturus, #KIT0204). The cDNA was amplified and the HG-U133 Plus GeneChip was used for the hybridization, and normalized across microarrays using the Robust MultiChip Average program. One-way ANOVA was performed using a conservative significance cut-off to identify informational genes that distinguished between the three cell classes: adventitia, media, and intima (Partek Pro microarray analysis suite, www.partek.com).

Cell Culture

Briefly, anonymous discard tissues of non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA), abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and carotid plaque (CP). The intimal layer was removed from the aortic tissue. The tissue was digested with collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and porcine pancreatic elastase (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). The cells were suspended in DMEM containing Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Supplement (#1152, ScienceCell, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal calf serum, Glutamax I, non-essential amino acids, 6mM HEPES, and antibiotics. Samples of cells (passage < 5) were analyzed by flow cytometry for cell type-specific marker proteins.

U937 cells for use in the elastolytic assays were cultured in RPMI media containing 10%FBS, and antibiotics. Prior to use in our experiments, the cells were differentiated in media containing 10 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) for 24 hours.

Expression Profiling

Whole genome gene expression profiles of vascular smooth muscle cells were analyzed in two independent batches. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed on the HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip according to the manufacturer's instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

The expression data was normalized in BeadStudio software (Illumina) using the cubic-spline method. The data was then imported into Partek Genomics Suite v6.5 (Partek Inc, Saint Louis, MO). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using a mixed model ANOVA. A gene list was then created using a median false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05. Inclusion of patient age and sex did not influence the model. Genes that were differentially expressed in VSMC derived from AAA compared to VSMC from CEA and NAA were subjected to gene ontology analysis.

Class prediction analysis was based on k-nearest neighbor classification (k=1 and k=3, based on a Euclidean distance measure). The misclassification rate of each model was estimated using complete leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV).

Elastolytic Activity

Tritiated elastin, which had been prepared as described previously, was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, Ca).11 Tissue culture wells (24/plate) were coated with 200μg [3H] elastin. Co-culture experiments were performed using a Transwell co-culture system (#3414, Corning Inc, Big Flats, NY). The VSMC were incubated for 24 hours in serum-free DMEM containing 20μg/ml lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (#L3024, Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). Experiments were performed with 1 × 105 cells in the well and/or with 0.5 × 105 cells in the transwell for 7 days before the solubilized [3H]-elastin was quantitated by counting an aliquot of the media in a β-scintillation counter. All assays were performed with three technical replicates. Activity is reported in total micrograms elastin degraded per well based on the specific activity of [3H] elastin.

Degradation of Mouse Aortic Elastin Ex Vivo

Serial sections of OCT-embedded infrarenal aortic tissue from C57/Bl6 mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, Maine) were mounted on coverslips. The sections were then examined using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61, Center Valley, Pennsylvania) at 200X. The tissue sections were cultured for 10 days with VSMC derived from AAA or NAA tissue, and reimaged.

Measurement of metalloproteinase production

Evaluation of matrix metalloproteinase production and activity were performed as previously described.11 Briefly, the VSMC cultured from AAA, CEA, and NAA tissue were plated in 6-well culture plates (Corning, Big Flats, NY) at a density of 0.5 × 106 and incubated in serum-free media for 7 days. For co-culture experiments, activated U937 cells (3 × 105) were suspended in transwells. Equal amounts of protein were resolved on 4-20% gradient gels or 12.5% gels containing 0.2% gelatin. The zymogram gels were incubated overnight in assay buffer then rinsed with deionized water and stained with Coomassie Blue. Western blotting was performed on proteins that were transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in PBST buffer for 1 hour at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibody toward MMP-2 or MMP-9 (ab37150, ab38898, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight. A peroxidase-chemiluminescent system (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) was used to detect bound primary. Expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA in VSMC was compared by qRT-PCR [Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY (assay ID: Hs01548727_ml, Hs00234579_ml, and Hs02758991_gl, respectively)]. Gene expression in AAA and CEA-VSMC relative to NAA-VSMC was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Statistics

For analysis of the elastolytic assay data, a one-way ANOVA was performed using SPSS vl9 (IBM, Armonk, NY) comparing mean μg elastin degraded and mean MMP-2 and MMP-9 production between experimental groups. Tukey's post hoc test was used to compare mean ug elastin degraded between the individual groups within experiments. The same analysis was carried out to compare MMP production in western blotting.

Results

Characterization of Cells

Cell cultures were obtained by enzymatic explantation techniques from fresh surgical discard tissues under a Humans Studies Committee protocol. All VSMC cultures used in experiments were negative by flow cytometry for cell markers CD1lc, CD20, CD3, CD31 and CD68 and were positive for alpha smooth muscle actin.

Expression Profiles of VSMC in culture

We performed gene expression profile analyses from 22 AAA, 29 CEA, and 17 NAA vascular smooth muscle cell lines, representing all available cell lines produced at the time of analysis. Characteristics of the patients from which the tissue was harvested are shown in Table I. The mean age between patients with AAA and CEA was similar. Patients from whom NAA tissue was harvested were generally younger than CEA or AAA patients. A majority of the AAA patients were male. The distribution of male and female patients was approximately equal for NAA and CEA patients.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients from which vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) were harvested for microarray analysis. VSMC were cultured from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), normal abdominal aorta (NAA), and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) tissues. (†=P<0.001, ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test).

| Tissue type (n) | Mean Age (±SE) | %Male, %Female | Mean Cell Passage Number (±SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA (22) | 69.8 (1.9) | 76%, 24% | 2.8(0.16) |

| NAA (17) | 45.6† (4.1) | 47%, 53% | 2.2 (0.12) |

| CEA (29) | 67.0 (2.0) | 53%, 47% | 2.6 (0.21) |

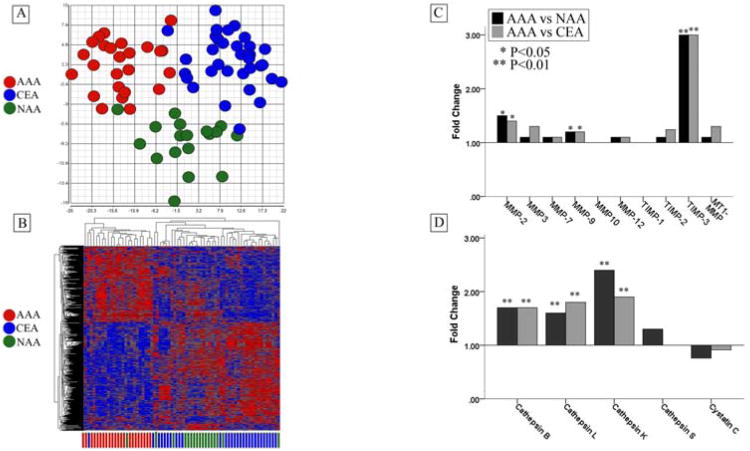

Using a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.05, we identified 816 genes which were differentially expressed by the VSMC derived from these tissue types. A principal component analysis (PCA) was plotted based on those genes and is shown in Figure 1A. In the PCA, the 3 distinct clusters clearly show the unique gene expression pattern of the cells derived from aortic aneurysm tissue and hierarchical clustering further demonstrates the very distinct pattern of aneurysm-derived cell types.

Figure 1.

(A) Principal Components Analysis and hierarchical clustering demonstrating distinct gene expression patterns of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) derived from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA, n=22) (red), non-dilated infrarenal aorta (NAA, n=17) (green), and carotid endarterectomy tissues (CEA, n=29) (blue). (B) Microarray data demonstrating relative gene expression of specific elastases and inhibitors between vascular smooth muscle cells cultured from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA, n=22), non-dilated infrarenal aorta (NAA, n=17), and carotid endarterectomy tissues (CEA, n=29). AAA-derived tissues exhibited significantly increased gene expression of several elastin-degrading endopeptidases including matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), cathepsin-B, cathepsin-L, and cathepsin-K. (*P<0.05, **=P<0.01, ANOVA)

We were able to validate the application of gene expression profiling to discriminate between VSMC derived from AAA, CEA, and NAA tissue with high accuracy using a class prediction analysis based on k-nearest neighbor classification (k=1 and k=3). Models were constructed containing a range of predictor genes. After cross-validation with LOOCV, the mean percent of correct classification of VSMC subset (AAA, NAA, CEA) by these models ranged from 73-90% with the 3-nearest neighbor classification containing 30 predictor genes performing most accurately. Table II outlines the performance of this model. The model correctly classified 20 out of 22 AAA cell lines (91%). Normal diameter aorta VSMC were correctly identified in 14 out of 18 cases (82%) and cells from CEA were correctly classified in 27 out of 29 cases (93%).

Table II.

Performance of class prediction analysis (k-nearest neighbor (k=3), 30 predictor genes).

| n | Proportion | Correct | Errors | % Correct | % Error | Std. Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Abdominal Aorta | 17 | 0.25 | 14 | 3 | 82.00 | 18.00 | 9.25% |

| Carotid Endarterectomy | 29 | 0.43 | 27 | 2 | 93.00 | 7.00 | 4.71% |

| Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm | 22 | 0.32 | 20 | 2 | 91.00 | 9.00 | 6.13% |

| Total | 68 | 1 | 61 | 7 | 89.71 | 10.29 | 3.69% |

| Confusion matrix (Real / Predicted) | |||||||

| NAA | CEA | AAA | |||||

| Normal Abdominal Aorta (NAA) | 14 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA) | 2 | 27 | 0 | ||||

| Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) | 1 | 1 | 20 | ||||

Expression Profiles of Microdissection of AAA Wall

Amplified RNA from microdissection specimens of the 3 principal layers of the aortic wall –intima, media and adventitia – was subjected to microarray analysis. We performed cluster analysis of these data to resolve whether there are consistent differences in expression which would allow us to specifically group the microdissected layers of the aortic wall. We identified 49 genes which highly significantly (p<0.0005) differentiated between these three layers of the aortic wall (Supplemental Figure 1).

Gene Ontology

Gene ontology analysis revealed that a number of functional classification groups were expressed differentially in AAA derived VSMC in comparison to NAA and CEA cells. Some of the most significantly enriched functional categories included genes related to axis specification, response to oxidative stress, pro-apoptotic pathways, the proliferation and migration of VSMC, several pro-inflammatory pathways, and proteolysis.

Our microarray data revealed a significant elevation of matrix-metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and matrix-metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) mRNA expression in AAA-derived VSMC relative to VSMC cultured from NAA and CEA tissue. Analysis of the microarray data also suggested significantly increased expression of the cysteine proteases, cathepsin B, cathepsin L, cathepsin K, and cathepsin S. The data did not reveal differences in expression of the endogenous MMP inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 or the cysteine protease inhibitor cystatin C between VSMC types. There was increased expression of TIMP-3 by AAA VSMC (Figure 1B).

Enhanced Elastolytic Activity of AAA-derived SMC

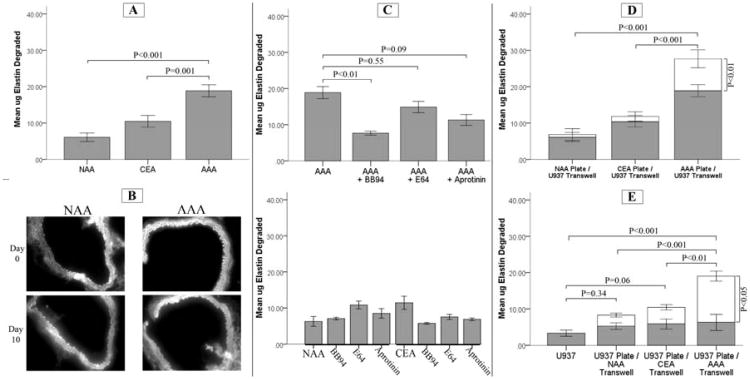

An assay of elastolytic activity of these cells (n=11/tissue type) was performed by culturing the cells on [3H]-labeled elastin-coated plates for 7 days. Cells derived from AAA consistently degraded significantly more elastin than cells derived from non-dilated abdominal aortas (18.9 ± 5.5μg vs 6.1 ± 3.9μg, P < 0.001) and carotid plaque derived cells (10.45 ± 5.5μg, P = 0.001) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Insoluble [3H]-elastin digestion (μg ± SE) by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA, n=11), non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA, n=11), and carotid endarterectomy plaque (CEA, n=1) cultured for 7 days. The AAA-derived cells degraded significantly more [3H]-elastin than VSMC cultured from CEA or NAA tissue. (B) VSMC cultured from NAA and AAA tissues were cultured for 10 days with mouse aortic tissue imaged with auto-fluorescence before and after. Representative images demonstrate diminished elastin in aortic tissue incubated with AAA-derived VSMC. (C) The effect of specific proteinase inhibitors on the in vitro degradation of insoluble [3H]-elastin. VSMC derived from AAA, NAA, and CEA (n=3 each) were cultured in serum free media in the presence or absence of BB94, (a broad inhibitor of matrix-metalloproteinases [5μM]), the serine protease inhibitor aprotinin (100μg/mL), and the cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (10μM). Only BB94 significantly reduced the elastin degraded by AAA-derived VSMC. (D) The effect of co-culture of VSMC in contact with [3H]-elastin with activated U937 macrophages in transwells. VSMC (n=11 each) were plated in [3H]-elastin coated culture wells for 7 days with activated U937 cells in transwell inserts. The shaded area of the histogram represents monoculture, and the open area represents co-culture conditions. The presence of activated U937 cells significantly increased elastin degradation only with AAA-VSMC compared to monoculture of SMC. (E) The effect of co-culture of activated U937 macrophagees in contact with [3H]-elastin with VSMC in transwells. VSMC derived from AAA (n=7), NAA (n=3), or CEA (n=3) were cultured for 7 days in transwells above [3H]-elastin coated plates with or without activated U937 cells. There was no effect of cell origin on elastin degradation when the VSMC were not in contact with the elastin. However, elastin degradation was only significantly increased in wells with AAA-VSMC in transwell co-culture with activated U937 macrophages.

The addition of inhibitors to the media [BB-94, a non-selective MMP inhibitor (5μM), a serine protease inhibitor, aprotinin (100μg/ml), and a cysteine protease inhibitor, E64 (10μM)] of NAA and CEA cells did not have a significant effect on elastolytic activity. In AAA derived cells, however, MMP inhibition with BB94 inhibited elastolysis by approximately 60 percent (7.6±0.9μg vs 18.9±5.5μg, P=0.008, n=3). Aprotinin and E64 did not result in significant reductions in elastolytic activity degrading 11.3±2.6μg vs 18.9±5.5μg, (P=0.09, n=3) and 14.9±2.7μg vs 18.9±5.5μg, (P=0.55, n=3), respectively (Figure 2C, 2D). Elastin degradation by VSMC required direct contact as cells suspended in transwell inserts above the labeled elastin resulted in low levels of elastolysis (5.0±2.9μg for NAA, 5.8±4.2μg for CEA, and 6.0±4.8μg for AAA derived VSMC (n=6).

MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Conditioned Media

A band consistent with pro-MMP-2 was detected both by zymography and by Western blotting in conditioned media from the VSMC. There was no significant difference in the VSMC production of pro-MMP-2 between the tissue of origin groups.

Active MMP-2, visualized as a 62 kD band on the gelatin zymogram, was most pronounced in VSMC derived from AAA tissue whereas very little active MMP-2 was detected in NAA and CEA cells (Figure 3A). A band consistent with activated MMP-2 was not seen on Western blotting, however, for any of the VSMC groups (Supplemental Figure 2). A low level of MMP-9 was detectable by zymography (but not by Western blotting) in the conditioned media from AAA-derived and CEA-derived SMC, but no band was seen at 92kDa in the NAA-derived VSMC.

Figure 3.

(A) Gelatin zymography of conditioned cell culture media (CM). Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) derived from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) were cultured in serum-free media for 7 days in the presence or absence of PMA-stimulated U937 cells in transwell inserts. Media from cultures of SMC alone was dominated by MMP-2 activity (62kDa) particularly in the AAA-derived VSMC. Media from co-cultures demonstrated consistent bands corresponding to MMP-9 activity (92 kD) and increased active MMP-2 activity relative to the monocultures, which was most pronounced from AAA-VSMC / U937 co-cultures. (B) Western blot analysis of conditioned cell culture media for MMP-2 and MMP-9 from co-culture experiments (representative blots are shown from n=6 for densitometry for each). MMP-9 (92 kD) was more highly expressed in the media from co-cultures with AAA-VSMC. The production of pro-MMP2 did not differ by SMC origin in the co-culture setting. However, significantly more active MMP-2 (62 kD) was present in cultures containing AAA-derived VSMCs. (C) Real-Time PCR in VSMC from monoculture as well as in cells after co-culture with activated U937 macrophages. At baseline, both MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression were significantly elevated in AAA-derived VSMC relative to NAA and CEA. In response to co-culture with activated macrophages, the MMP-9 expression increased dramatically in both NAA and AAA VSMC. Whereas expression of MMP-2 mRNA significantly decreased in both cell types under the co-culture conditions. (* P<0.05, **P<0.01, ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test)

Elastolysis in VSMC – Macrophage Co-Cultures

We analyzed elastolytic activity in a co-culture system where VSMC were cultured in the presence of PMA activated U937 cells suspended in transwell inserts. In co-cultures containing AAA-derived VSMC with U937 cells, there was an over 40% increase in elastolytic activity when compared to cultures containing AAA-VSMC alone (26.67±8.2μg, n=11, vs 18.9±5.5μg, n=11, P<0.001). In contrast, elastolytic activity was not significantly affected with the addition of U937 cells to NAA (6.83±5.38μg, n=11, vs 6.09±3.89μg, n=11, P=1.0) or CEA (11.81±4.24μg, n=11, vs 10.45±5.40μg, n=11, P=0.99) derived VSMC cultures (Figure 2D).

Elastolytic activity was also measured in co-cultures with U937 cells plated on the radiolabeled elastin with the VSMC suspended in transwell inserts (Figure 2E). When cultured alone in contact with insoluble elastin, the activated U937 cells exhibited only a small amount of elastolytic activity (3.3±2.9μg per well, n=3). We similarly saw relatively little elastolytic activity of the VSMC, regardless of tissue of origin, when cultured in the transwell alone and not in contact with the elastin. Co-culturing NAA or CEA-derived VSMC with the U937 cells did not significantly augment elastin degradation compared to either cell type alone. When AAA-derived VSMC were suspended above the U937 cells in transwell inserts, there was an approximate 6-fold increase in elastolytic activity compared to VSMC in the transwell alone (19.0±3.55μg, P<0.001, n=7), and compared to activated macrophages alone (P<0.001).

MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Co-cultures

Zymography using conditioned media from activated U937 monocytes demonstrated the presence of pro-enzyme forms of both MMP-9 and MMP-2 (Figure 3A). The VSMC cultures demonstrated relatively little MMP-9 activity, but all cell lines showed activity at 72kDa, consistent with pro-MMP-2. The AAA and CEA-derived cell lines appeared to have more MMP-2 activity than cells derived from NAA, including the presence of activated MMP-2. Culturing the VSMC in the presence of U937 cells in transwells led to increased amounts of active MMP-2 in the culture media (62 kDa band) in all VSMC types, relative to VSMC cultured alone. This effect was much more pronounced with AAA and CEA-derived VSMC in comparison to NAA-VSMC (Figure 3A). Significant amounts of MMP-9 were detected in all wells containing U937 cells.

Western blotting of conditioned media from co-cultures containing AAA-derived VSMCs demonstrated a uniformly higher concentration of MMP-9, with a mean relative density 3.8 fold greater than in NAA-U937 co-cultures (P<0.001, n=6) (Figure 3D). In concordance to our results from gelatin zymography, media from wells containing co-cultured U937 and VSMC consistently demonstrated the presence of active MMP-2, with a band at 62 kDa. Once again, the increase of active MMP-2 was most pronounced in co-cultures containing AAA derived VSMCs. The density of the band corresponding to active MMP-2 was approximately 6 times that of the band observed for NAA-VSMC cultures (P=0.01, n=6) (Figure 3D).

MMP-2 and MMP-9 Expression

Under basal conditions, the level of MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA expression was significantly higher in the AAA-derived VSMC. Cells cultured from AAA tissue exhibited 2.0 fold higher expression of MMP-2 compared to NAA-VSMC (P<0.05, n=11) and 7.3 fold increased expression of MMP-9 mRNA (P<0.01, n=11) (Figure 3B).

The presence of U937 cells suspended in transwell-inserts did not increase expression of MMP-2 mRNA by VSMC. In fact, MMP-2 expression decreased by a small but statistically significant amount (P<0.05, n=3). Co-culture with U937 monocytes led to a large relative increase in the expression of MMP-9 mRNA in both AAA and NAA VSMC (P<0.001, n=3) (Figure 3C). MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA production by U937 cells was not significantly affected by co-culture with VSMC (Supplemental Figure 3).

Discussion

The abdominal aortic aneurysm is a progressive degenerative disease of a major vascular conduit with considerable impact on patient mortality and healthcare costs. The aneurysmal change is frequently localized to the infrarenal segment of the abdominal aorta although it can extend into the adjacent common and internal iliac vessels. Development of a weakened aortic wall is associated with severe destruction of the medial elastic fibers. This study sought to demonstrate that the VSMC which populate the aneurysm wall have a unique phenotype that directly contributes to the pathogenesis of the aneurysm. We also sought to develop a mechanistic understanding of the role of the VSMC in the destruction of medial elastin that characterizes AAA.9

Traditionally, it has been hypothesized that the destruction of extracellular matrix in AAA is primarily a consequence of an exuberant chronic inflammatory infiltrate that is responsible for the elaboration of elastases and other proteases which damage the medial matrix structure of the aorta.6 Substantial work has shown that the intramural macrophages may have a central role,1–5,7–9 but more recent studies have also focused on the contributions of neutrophils,11, 12 mast cells13 and other infiltrating cells.15, 16 Much of the supporting evidence for the central role of inflammation in AAA comes from mouse models where nearly all manners of anti-inflammatory therapy inhibit aneurysm formation.17-19 In humans, however, anti-inflammatory treatment has not been similarly successful.20

The VSMC of the aorta have received less attention than the inflammation as a contributor to aneurysmal change. Some studies have shown potential secondary participation of these cells in AAA pathogenesis due to a reduction in the quantity or activity of medial VSMC. The reduction in VSMC has been hypothesized to limit matrix repair in the damaged aorta.21 There is also inferential evidence that the VSMC may play a more direct role in aneurysm formation.22

By examining the complete expression profile of a large number of pure, early passage VSMC cultures from aneurysmal and non-aneurysmal infrarenal aorta, we have shown that VSMC derived from AAA exhibit a unique pattern of gene expression that is distinct from VSMC derived from non-dilated abdominal aortic tissue with a high degree of predictability. The microdissected aneurysm specimens suggested that the expression profiles of the cells in the intima were distinct from that of the media and adventitia in aortic specimens. This would be consistent with a distinct process of disease development of intimal atherosclerosis and aneurysmal dilatation. Therefore, to optimize the collection of aneurysm specific pathogenic cells, we grossly removed the intima prior to cell culture of the aortic specimens Furthermore, we also compared the profile of the aneurysm-derived VSMC to VSMC derived from carotid plaque, and confirmed that the profile of the AAA cells was distinct from that of atherosclerotic plaque which further supports the concept that the aneurysm cell phenotype is unique.

These crucial observations demonstrate that the AAA-derived cells have either an intrinsic or acquired phenotype that may contribute to the degeneration of the aorta. These experiments cannot demonstrate how these AAA-derived cells developed their unique phenotype, or the mechanism by which this phenotype persists relative to other VSMC even when exposed to common in vitro culture conditions. A detailed discussion of the potential sources of this unique phenotype has been reviewed in detail, in a prior review.9 Briefly, studies of the long-term growth characteristics of aneurysm-derived VSMC compared to similarly cultured VSMC from non-aneurysmal vasculature have demonstrated consistent differences,21, 23-25 even when derived from the same patient.26 The specific ontogeny of the distal aortic VSMC may also play an important role in the particular susceptibility of this vascular segment to aneurysmal degeneration. It is notable that the external iliac arteries, which are highly aneurysm resistant, form much later in gestation and from different precursors compared to the adjacent dorsal aorta-derived and aneurysm-prone infrarenal aorta, common iliac and internal iliac vessels.27, 28

To understand how this novel phenotype of the AAA-derived cells may predispose to AAA development, we focused on determining the role of these cells with respect to the elastic fiber degeneration characteristic of the AAA. We confirmed that within the aneurysm-specific expression profile is upregulation of several proteases of metalloprotease and cysteine classes that are capable of elastolysis. Also potentially informative were the findings of the MMP inhibitors including a lack of upregulation of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 while there was considerable upregulation of TIMP-3. The lack of increased TIMP-1 or 2 in the setting of increased MMP activity suggests an imbalanced proteolytic state,29, 30 although the role of TIMP-3 is unclear. In whole aneurysm tissue, others have shown significantly increased expression of TIMP-3 in AAA,31 but both gene expression32 and protein production33 have been shown to be decreased in thoracic aortic aneurysms. This unique role of TIMP-3 in AAA development is also supported by a genetic variant of TIMP-3 (nt-1296) that has been found to be associated with familial AAA.34

Of the elastolytic matrix metalloproteases, only MMP-2 and MMP-9 demonstrated significant upregulation in the AAA-derived VSMC, which we confirmed by qRT-PCR. However, we also found significant upregulation of several cysteine proteases that are capable of contributing to elastolysis. By incubating the VSMC on labeled insoluble elastin as well as murine aortic sections, we confirmed that the AAA-derived VSMC were able to degrade significantly more insoluble elastin than cells derived from non-dilated infrarenal aorta or from carotid plaque. Using broad-spectrum class-selective inhibitors, this potent elastolytic activity appeared to be primarily mediated by the activity of MMPs.

This critical finding confirms our hypothesis that the intrinsic VSMC found in AAA can actively participate in the matrix degradation process through MMP-dependent elastolytic activity. However, it left open the relative participation of the aortic VSMC and the inflammatory cells in the degradation of elastin. To evaluate the potential interaction of VSMC with macrophages in the degradation of elastin, we performed the co-culture experiments using activated U937 cells.35 Remarkably, the elastolytic activity of AAA-derived VSMC was substantially augmented in the setting of co-culture with the activated macrophages – a synergistic effect not seen in co-culture with NAA or CEA-derived cells.

The unique elastolytic activity of the AAA and macrophage cell co-culture was associated with an incredibly large increase in the expression of MMP-9 mRNA in the co-cultured VSMC. At the same time, it was associated with a decreased expression of MMP-2 mRNA. Somewhat surprisingly, we saw a nearly identical effect of co-culture on MMP expression in the cells derived from non-aneurysmal aorta – cells that did not increase their elastolytic activity in co-culture. There was no appreciable effect on the mRNA expression of either MMP-9 or MMP-2 in the macrophages when co-cultured with VSMC.

Despite the similar response of both AAA-derived and NAA-derived cells to MMP expression in the setting of activated macrophages, co-culture of the AAA-derived cells was associated with a significantly greater increase in MMP-9 protein in the conditioned media compared to the NAA-derived cells. This would suggest substantial post-transcriptional control of MMP-9 production that occurs in normal cells, but is not effective in the AAA-derived VSMC. We also found that there was substantially more activated MMP-2 in the conditioned media from the AAA-derived VSMC co-cultured with the activated U937.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the VSMC which populate the AAA have a unique pro-elastolytic phenotype that is augmented in the presence of activated macrophages. This effect appears to occur via a post-transcriptional failure of MMP-9 synthesis control leading to increased production and activation of elastolytic MMPs. These are unique and important findings regarding the pathobiology of the disease that create new opportunities with respect to therapies which can result in effective aneurysm inhibition. Further study is needed to determine the inter- and intracellular mechanisms which allow for the synergistic over production of elastolytic proteases, particularly MMP-9, by the aneurysm-derived VSMC in the presence of activated macrophages.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Heatmap based on Affymetrix U133 genechip demonstrating 49 genes which are informative in segregating the three microdissected regions of the arterial wall: intima, media, and adventitia. RNA was extracted after microdissection of the arterial wall from three patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. The RNA was converted to cDNA and amplified prior to hybridization with the genechip. The media specimen from Patient #1 was analyzed in duplicate due to poor amplification of the (A) specimen.

Supplemental Figure 2: Western blot analysis of conditioned cell culture media for MMP-2 and MMP-9. VSMC derived from AAA, NAA, and CEA were cultured in serum free media. The media was collected after 7 days of cell growth and equal volumes from each well were subjected to western blot analysis for MMP-2 and MMP-9. In media from VSMC-only cultures, relatively equal amounts of MMP-2 (72 kD) were observed. No MMP-9 was detected in the media containing only VSMC (n=6).

Supplemental Figure 3: Real-Time PCR analysis was used to compare total mRNA levels in PMA-activated U937 monocytes cultured alone, and in the presence of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) derived from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Error bars represent 95% CI. MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression by U937 cells was not significantly affected by co-culture with VSMC derived from AAA, CEA, or NAA tissue (n=3).

Clinical Relevance Paragraph.

The only current therapeutic modalities for treatment of the abdominal aortic aneurysm rely on physical exclusion of the aneurysm — therapies associated with substantial risks and costs. Medical therapies which block the progressive destruction of the aortic wall have great potential to reduce the need for surgical treatment. These experiments demonstrate that the intrinsic smooth muscle cells in the wall of the aneurysmal aorta are uniquely capable of enzymatic destruction of elastin and potentiate the elastolytic capability of the inflammatory cells. Effective therapy for aneurysms may require treatments targeting the dysfunctional activities of the intrinsic smooth muscle cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Stephen M. Schwartz, M.D., Ph.D. at the University of Washington for all of his help conceptualizing the project.

Funding Sources: Supported by the Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute (JAC), the American Heart Association 0765432Z (JAC), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K08 HL84004 (JAC) and P50 HL083762 (RWT), the Society for Vascular Surgery Foundation (JAC), the American College of Surgeons (JAC), the National Institute of Aging R01 AG037120 (JAC), the Department of Veterans Affairs (JAC)

Footnotes

Presented at the Plenary Session (May 29) of the 2013 Vascular Annual Meeting (San Francisco, CA) as the Resident Research Award Prize winner.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Koch AE, Haines GK, Rizzo RJ, Radosevich JA, Pope RM, Robinson PG, et al. Human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Immunophenotypic analysis suggesting an immune-mediated response. Am J Pathol. 1990 Nov;137(5):1199–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeper NJ, Tedesco MM, Kojima Y, Schultz GM, Kundu RK, Ashley EA, et al. Apelin prevents aortic aneurysm formation by inhibiting macrophage inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 May;296(5):H1329–1335. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01341.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, et al. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000 Jun;105(11):1641–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakahashi TK, Hoshina K, Tsao PS, Sho E, Sho M, Karwowski JK, et al. Flow loading induces macrophage antioxidative gene expression in experimental aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002 Dec 1;22(12):2017–22. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000042082.38014.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiraya S, Miyake T, Aoki M, Yoshikazu F, Ohgi S, Nishimura M, et al. Inhibition of development of experimental aortic abdominal aneurysm in rat model by atorvastatin through inhibition of macrophage migration. Atherosclerosis. 2009 Jan;202(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobrin PB, Baumgartner N, Anidjar S, Chejfec G, Mrkvicka R. Inflammatory aspects of experimental aneurysms. Effect of methylprednisolone and cyclosporine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996 Nov 18;800:74–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb33300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curci JA, Liao S, Huffman MD, Shapiro SD, Thompson RW. Expression and localization of macrophage elastase (matrix metalloproteinase-12) in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 1998 Dec 1;102(11):1900–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vollmar JF, Paes E, Pauschinger P, Henze E, Friesch A. Aortic aneurysms as late sequelae of above-knee amputation. Lancet. 1989 Oct 7;2(8667):834–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curci JA. Digging in the “soil” of the aorta to understand the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Vascular. 2009 Jun;17(1):S21–29. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annabi B, Shédid D, Ghosn P, Kenigsberg RL, Desrosiers RR, Bojanowski MW, et al. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activities in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2002 Mar;35(3):539–46. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.121124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banda MJ, Werb Z, McKerrow JH. Elastin degradation. Methods Enzymol. 1987;144:288–305. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)44184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houard X, Touat Z, Ollivier V, Louedec L, Philippe M, Sebbag U, et al. Mediators of neutrophil recruitment in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Cardiovasc Res. 2009 Jun 1;82(3):532–41. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagano MB, Zhou H, Ennis TL, Wu X, Lambris JD, Atkinson JP, et al. Complement-dependent neutrophil recruitment is critical for the development of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circulation. 2009 Apr 7;119(13):1805–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun J, Zhang J, Lindholt JS, Sukhova GK, Liu J, He A, et al. Critical role of mast cell chymase in mouse abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2009 Sep 15;120(11):973–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galle C, Schandené L, Stordeur P, Peignois Y, Ferreira J, Wautrecht JC, et al. Predominance of type 1 CD4+ T cells in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005 Dec;142(3):519–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caligiuri G, Rossignol P, Julia P, Groyer E, Mouradian D, Urbain D, et al. Reduced immunoregulatory CD31+ T cells in patients with atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006 Mar;26(3):618–23. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000200380.73876.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokoyama U, Ishiwata R, Jin MH, Kato Y, Suzuki O, Jin H, et al. Inhibition of EP4 signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm formation. Plos One. 2012;7(5):e36724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King VL, Trivedi DB, Gitlin JM, Loftin CD. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition with celecoxib decreases angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006 May;26(5):1137–43. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216119.79008.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong PJ, Franklin DP, Carey DJ, Elmore JR. Suppression of experimental aortic aneurysms: comparison of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005 Mar;19(2):248–57. doi: 10.1007/s10016-004-0174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Englesbe MJ, Wu AH, Clowes AW, Zierler RE. The prevalence and natural history of aortic aneurysms in heart and abdominal organ transplant patients. J Vasc Surg. 2003 Jan;37(1):27–31. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Candales A, Holmes DR, Liao S, Scott MJ, Wickline SA, Thompson RW. Decreased vascular smooth muscle cell density in medial degeneration of human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol. 1997 Mar;150(3):993–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louwrens HD, Kwaan HC, Pearce WH, Yao JS, Verrusio E. Plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor expression by normal and aneurysmal human aortic smooth muscle cells in culture. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg Off J Eur Soc Vasc Surg. 1995 Oct;10(3):289–93. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(05)80044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson EL, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, Whittemore AD, Knox J, Libby P. Death of smooth muscle cells and expression of mediators of apoptosis by T lymphocytes in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 1999 Jan 5;99(1):96–104. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes DR, López-Candales A, Liao S, Thompson RW. Smooth muscle cell apoptosis and p53 expression in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996 Nov 18;800:286–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb33334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob T, Hingorani A, Ascher E. Examination of the apoptotic pathway and proteolysis in the pathogenesis of popliteal artery aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg Off J Eur Soc Vasc Surg. 2001 Jul;22(1):77–85. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao S, Curci JA, Kelley BJ, Sicard GA, Thompson RW. Accelerated replicative senescence of medial smooth muscle cells derived from abdominal aortic aneurysms compared to the adjacent inferior mesenteric artery. J Surg Res. 2000 Jul;92(1):85–95. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godfrey M, Nejezchleb PA, Schaefer GB, Minion DJ, Wang Y, Baxter BT. Elastin and fibrillin mRNA and protein levels in the ontogeny of normal human aorta. Connect Tissue Res. 1993;29(1):61–9. doi: 10.3109/03008209309061967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tilson M. Chicken embryology of human aneurysm-resistant arteries. Matrix Biol. 2006;(1)(25):S57. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard EW, Bullen EC, Banda MJ. Preferential inhibition of 72- and 92-kDa gelatinases by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jul 15;266(20):13070–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamarina NA, McMillan WD, Shively VP, Pearce WH. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in aneurysms and normal aorta. Surgery. 1997 Aug;122(2):264–271. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90017-9. discussion 271–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrell TWG, Burnand KG, Wells GMA, Clements JM, Smith A. Stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 are overexpressed in the wall of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2002 Jan 29;105(4):477–82. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blunder S, Messner B, Aschacher T, Zeller I, Türkcan A, Wiedemann D, et al. Characteristics of TAV- and BAV-associated thoracic aortic aneurysms--smooth muscle cell biology, expression profiling, and histological analyses. Atherosclerosis. 2012 Feb;220(2):355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikonomidis JS, Jones JA, Barbour JR, Stroud RE, Clark LL, Kaplan BS, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and endogenous inhibitors within ascending aortic aneurysms of patients with Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2006 Jul 4;114(1 Suppl):I365–370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogata T, Shibamura H, Tromp G, Sinha M, Goddard KAB, Sakalihasan N, et al. Genetic analysis of polymorphisms in biologically relevant candidate genes in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2005 Jun;41(6):1036–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro SD, Campbell EJ, Welgus HG, Senior RM. Elastin degradation by mononuclear phagocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;624:69–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Heatmap based on Affymetrix U133 genechip demonstrating 49 genes which are informative in segregating the three microdissected regions of the arterial wall: intima, media, and adventitia. RNA was extracted after microdissection of the arterial wall from three patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. The RNA was converted to cDNA and amplified prior to hybridization with the genechip. The media specimen from Patient #1 was analyzed in duplicate due to poor amplification of the (A) specimen.

Supplemental Figure 2: Western blot analysis of conditioned cell culture media for MMP-2 and MMP-9. VSMC derived from AAA, NAA, and CEA were cultured in serum free media. The media was collected after 7 days of cell growth and equal volumes from each well were subjected to western blot analysis for MMP-2 and MMP-9. In media from VSMC-only cultures, relatively equal amounts of MMP-2 (72 kD) were observed. No MMP-9 was detected in the media containing only VSMC (n=6).

Supplemental Figure 3: Real-Time PCR analysis was used to compare total mRNA levels in PMA-activated U937 monocytes cultured alone, and in the presence of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) derived from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), non-dilated abdominal aorta (NAA) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Error bars represent 95% CI. MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression by U937 cells was not significantly affected by co-culture with VSMC derived from AAA, CEA, or NAA tissue (n=3).