Abstract

Collagen XXIII is a transmembrane collagen previously shown to be upregulated in metastatic prostate cancer that has been used as a tissue and fluid biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer and prostate cancer. To determine whether collagen XXIII facilitates cancer cell metastasis in vivo and to establish a function for collagen XXIII in cancer progression, collagen XXIII knockdown cells were examined for alterations in in vivo metastasis as well as in vitro cell adhesion. In experimental and spontaneous xenograft models of metastasis, H460 cells expressing collagen XXIII shRNA formed fewer lung metastases than control cells. Loss of collagen XXIII in H460 cells also impaired cell adhesion, anchorage-independent growth, and cell seeding to the lung, but did not affect cell proliferation. Corroborating a role for collagen XXIII in cell adhesion, overexpression of collagen XXIII in H1299 cells, which do not express endogenous collagen XXIII, enhanced cell adhesion. Consequent reduction in OB-cadherin, alpha-catenin, gamma-catenin, beta-catenin, vimentin, and galectin-3 protein expression was also observed in response to loss of collagen XXIII. This study suggests a potential role for collagen XXIII in mediating metastasis by facilitating cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion as well as anchorage-independent cell growth.

Keywords: collagen, metastasis, adhesion, anchorage-independence

Introduction

The role of the tumor microenvironment is increasingly understood to be critical in promoting tumor growth, survival and dissemination (Joyce and Pollard 2009, Whiteside 2008). Stromal components, including fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and blood vessels contribute to this microenvironment along with extracellular matrix elements such as laminin, fibronectin, and a variety of collagens. Although many studies have focused on the role of collagens that are secreted into the tumor extracellular matrix, transmembrane collagens, such as collagens XIII, XVII, XXIII and XXV, have been infrequently studied for their role in promoting tumor growth, invasion and metastasis.

Collagen XXIII is a member of the membrane-associated-collagens-with-interrupted-triple-helices (MACIT) family (Franzke et al 2005). It is structurally similar to collagen XIII and XXV—each with four noncollagenous and three collagenous domains, a short intracellular region with no known signaling capability, and a juxtamembranous furin-cleavage site (Banyard et al 2003, Hashimoto et al 2002, Pihlajaniemi and Tamminen 1990, Vaisanen et al 2004). Collagen XVII, another MACIT, has an extended intracellular domain, an ectodomain with sixteen noncollagenous and fifteen collagenous domains, and is cleaved by members of the a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase (ADAM) family (Franzke et al 2002, Franzke et al 2004, Franzke et al 2009).

Alterations in transmembrane collagens—genetic mutations, abnormal processing, or overexpression—are directly associated with disease, demonstrating the importance of transmembrane collagen function. In Alzheimer’s diseased tissue, the collagen XXV ectodomain binds to amyloid beta peptides within amyloid plaques (Hashimoto et al 2002) and its ability to regulate amyloid fibril formation in vitro has been demonstrated (Kakuyama et al 2005, Osada et al 2005, Soderberg et al 2005). Moreover, overexpression of collagen XXV in mice contributes to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis (Tong et al 2010) and a genetic association between collagen XXV and Alzheimer’s disease has also been reported (Forsell et al 2010).

Collagen XXIII expression is enriched in the highly metastatic rat prostate carcinoma cell line, AT6.1, as compared to sublines with lower metastatic potential (Banyard et al 2003). Furthermore, using patient samples, collagen XXIII was experimentally validated as a biomarker for NSCLC detection and recurrence (Spivey et al 2010) and prostate cancer recurrence (Banyard et al 2007). These strong correlations prompted our exploration of collagen XXIII function in cancer metastasis.

Potential functions for collagen XXIII may be inferred from studies on other transmembrane collagens. Membrane-associated collagen XIII, for example, has been implicated in mediating muscle fiber attachment to the underlying basement membrane. Transgenic mice expressing altered collagen XIII lacking the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains exhibit myopathy and fibroblasts derived from these same mice exhibit impaired adhesion to collagen IV in vitro relative to fibroblasts expressing the membrane-associated form (Kvist et al 2001). Blocking collagen XIII-collagen IV interactions with soluble collagen XIII ectodomain also results in decreased fibroblast adhesion (Vaisanen et al 2004, Vaisanen et al 2005). Corneal epithelial cells, which express endogenous cell surface collagen XXIII, also exhibit impaired adhesion to collagen IV in the presence of soluble collagen XXIII (Gordon 2005).

Using a genetic approach to manipulate collagen XXIII levels in human and rat carcinoma cell lines, we investigated the role of collagen XXIII in cancer cell metastasis in both spontaneous and experimental models of metastasis, in vivo. We further investigated whether collagen XXIII has a functional role in mediating cell morphology, cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion, or anchorage-independent growth. Our results suggest that collagen XXIII mediates both heterotypic and homotypic cell adhesion. In light of these results, we examined the effects of collagen XXIII knockdown in vitro on the expression of proteins with known roles in cell morphology or adhesion—including OB-cadherin, α-, β-, and γ-catenin, vimentin, galectin-3 and members of the integrin family. In summary, our findings suggest that collagen XXIII contributes to successful cancer cell metastasis in part through its function in cell adhesion and that changes in collagen XXIII expression affect other proteins with structural and adhesive roles.

Results

Generation of stable cell lines

Collagen XXIII was originally identified in the highly metastatic rat Dunning prostate carcinoma cell line AT6.1 in a screen for potential mediators of prostate cancer metastasis (Banyard et al 2003). To determine whether collagen XXIII has a necessary role in tumorigenesis and metastasis, cell lines stably expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) or micro RNAs (miRNA) were employed. Clonal H460 cell lines stably expressing the pRS vector encoding no shRNA (pRS) or shRNA against GFP (shGFP) were compared to H460 cell lines stably expressing one of two unique shRNA sequences targeting the coding sequence of collagen XXIII (sh#57 and sh#58) (Supplemental Figure 1A). For a subset of experiments, additional cell lines were used in parallel: AT6.1 parental and clonal AT6.1 cell lines that stably express pcDNA6.2 control or collagen XXIII specific miRNA; H1299 cells expressing control shRNA or collagen XXIII shRNA. H1299 cells expressing control pcDNA-DEST40 or overexpressing collagen XXIII as well as H460 sh#57 and sh#58 cells with rescued collagen XXIII expression were used as additional controls (Supplemental Figures 1B-D).

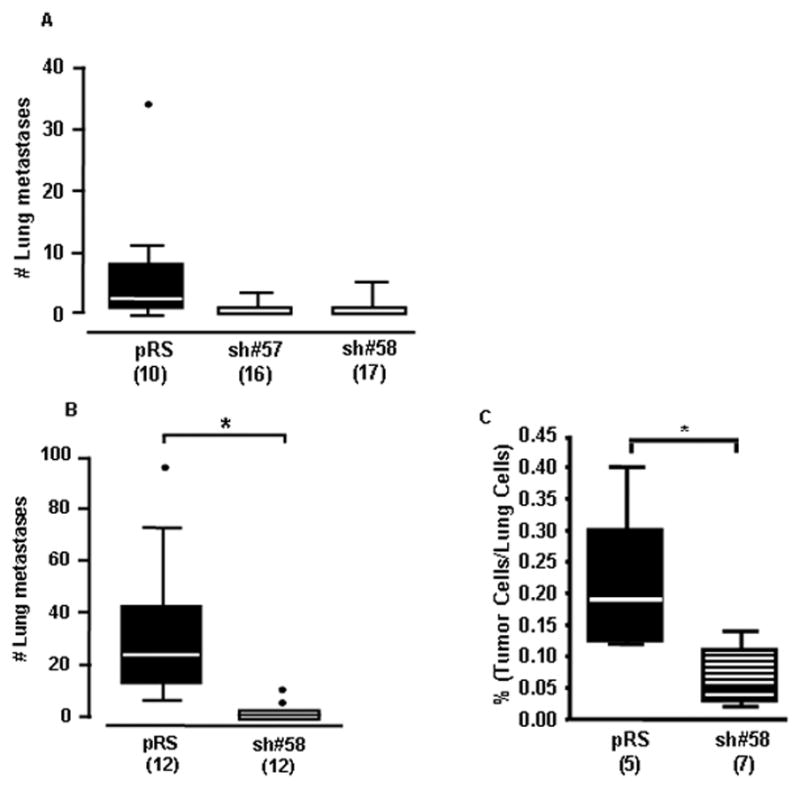

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on experimental and spontaneous mouse models of metastasis

In two in vivo models of metastasis, metastasis formation in the lung was enhanced in mice injected with control cells expressing high (pRS) levels of collagen XXIII compared to mice injected with collagen XXIII-knockdown cells (sh#57 or sh#58). In the spontaneous metastasis model, where lung metastasis is assessed 3 weeks after primary tumor resection, mice in the control group had an average of 7.9 lung nodules as compared to 0.6 and 1.3 in the knockdown groups (One way ANOVA, p<0.001) (Figure 1A). For the metastasis experiments, mice with tumors greater than 1cm3 were not included in the analysis. Therefore, differences in tumor size were not responsible for the reduction in metastasis observed in the knockdown group, as the average primary tumor volume was similar between groups (Supplemental Figure 2A). Endogenous collagen XXIII expression in control tumors was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Supplemental Figure 2B&C). A similar result was observed in a subsequent spontaneous metastasis experiment (Supplemental Figure 3A). These observations were validated in an experimental model of metastasis, which employs tail vein inoculation and recapitulates the later stages of metastasis, after the cells have exited the primary site and entered into the blood stream. Control group mice had on average more metastatic lung nodules than mice in the collagen XXIII knockdown group, with a mean of 28.75 and 0.833 lung nodules, respectively (t-test, p<0.01) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Loss of collagen XXIII inhibits spontaneous and experimental H460 cell metastasis and cell retention in the lung.

A) Female SCID mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2×106 control (pRS) or collagen XXIII knockdown (sh#57 and sh#58) cells into the right flank. Tumors were aseptically resected after 3 weeks and the lungs were collected three weeks post-resection. The number of mice per group is indicated in parentheses as mice were only included in the analysis if their tumor volume was between 100 and 1000 mm3. Box and whiskers plot (Tukey) indicates the average number of lung metastases per mouse in each group (one way ANOVA, p<0.001). B) Female SCID mice were inoculated intravenously with 1×106 H460 pRS or sh#58 cells. After 40 days, lungs were collected and analyzed for metastases. Box and whiskers plot (Tukey) designates the average number of experimental lung metastases per mouse in each group (t-test, *p<0.01). C) Nude mice were inoculated intravenously with 2.5×106 CMFDA-labeled control (pRS) or knockdown (sh#58) H460 cells. After 5 hours, lungs were perfused and digested mechanically and enzymatically. The proportion of labeled tumor cells within 5×105 total cells was determined for each mouse using the FACSCalibur system (t-test; *p=0.01).

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on cell retention in the mouse lung after hematogenous dissemination

In an attempt to understand whether collagen XXIII enhances cancer cell retention in the lung after hematogenous metastasis in vivo, the number of H460 control and knockdown cells present in the lung at early time points after intravenous inoculation was determined. The relative proportion of adherent H460 pRS or sh#58 CMFDA-labeled tumor cells was assessed using flow cytometry. H460 pRS cells were present in the lungs at higher proportions than the H460 sh#58 cells, representing 0.21% and 0.07% of the total lung cell population, respectively (t-test; p=0.01) (Figure 1C). A similar trend was seen when comparing the H460 pRS and sh#57 cell lines in a separate experiment (Supplemental Figure 3B).

Detection of collagen XXIII on the surface of H460 cells

Collagen XXIII localization in H460 cells could provide insight into its function as a potential mediator of metastasis. Collagen XXIII is a transmembrane protein that primarily localizes to the Golgi apparatus and the plasma membrane (Veit et al 2007). Using immunofluorescence, we examined the cellular localization of endogenous collagen XXIII in H460 cells. In unpermeabilized H460 pRS cells, cell surface collagen XXIII was found at sites of cell-cell contacts (Supplemental Figure 4A), whereas intracellular gamma-catenin was not detected (Supplemental Figure 4B). When cells were not engaged in cell-cell contacts, especially when seeded at low densities, a more diffuse pattern of cell-surface staining was observed. These results suggest that cell-surface collagen XXIII is enriched at sites of cell-cell contacts. Intracellular collagen XXIII was detected in the Golgi apparatus (Supplemental Figure 4C) and gamma-catenin was also detected at sites of cell-cell contacts (Supplemental Figure 4D).

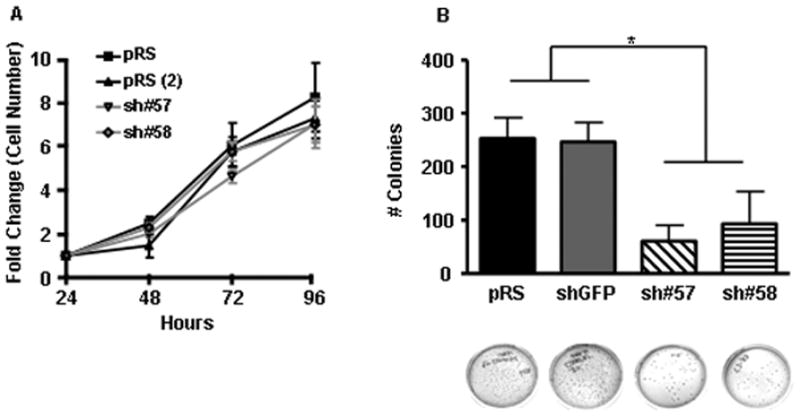

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on cell proliferation

Certain proteins regulate cell proliferation and loss of these proteins can alter a cell’s ability to form macroscopic metastasis, in vivo. To examine whether collagen XXIII affects cell proliferation in vitro, stable cell lines were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to grow in the presence of serum for 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours followed by fluorescent cell labeling. Comparison of relative fluorescent units (RFUs) at each time point revealed highly similar RFUs, indicating that collagen XXIII does not provide a growth advantage for cells in vitro (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Loss of collagen XXIII affects colony formation in soft agar but not cell proliferation in vitro.

A) To assess the role of collagen XXIII in cell proliferation, control and knockdown cell lines were seeded in triplicate and grown in complete media for 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours. Relative cell number per well was determined using CyQUANT reagent. For each cell line, the average number of cells present at each time point was normalized to the average number of cells present 24 hours after seeding. Shown are the mean of three independent experiments ± SEM. B) H460 control and knockdown cells were assessed for their ability to form colonies in soft agar. Shown are the mean +/− SEM of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Representative images of crystal violet stained colonies are included for each cell line. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (*p<0.001) between the means of the control (pRS and shGFP) and knockdown (sh#57 and sh#58) cell lines as determined by mixed model ANOVA.

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on anchorage-independent growth

Cancer cells are characterized by anchorage-independence—an ability to survive and proliferate in the absence of a two-dimensional adhesive substrate. Analysis of colony formation efficiency of H460 control or knockdown cell suspensions, revealed a role for collagen XXIII in anchorage-independent cell growth. Control cells formed significantly more colonies in soft agar than knockdown cells. Specifically, of the 500 cells initially seeded in agar, a mean of 253 pRS, 247 shGFP, 61 sh#57, and 93 sh#58 cells formed detectable colonies within two weeks with plating efficiency values of 51%, 49%, 12%, and 19%, respectively (Mixed model ANOVA; p <0.001) (Figure 2B).

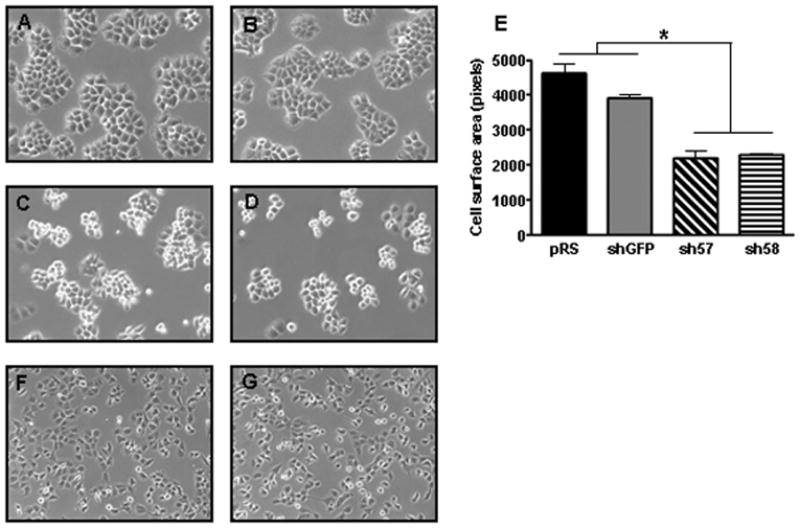

Altered collagen XXIII protein expression affects cell morphology

Cell surface expression of collagen XXIII may influence H460 cell shape. To assess whether silencing collagen XXIII influences H460 cell morphology, phase-contrast microscopy was used to analyze changes in cell shape between stable control and knockdown H460 cell lines. In cell lines with high collagen XXIII levels, individual cells appear spread—characterized by cellular protrusions and cell-substratum attachments—especially at early time points after seeding. Knockdown cells, in contrast, appear more rounded with less surface area and fewer attachment sites (Figure 3A-D). Specifically, the average surface area (measured in pixels) of the control cells (pRS, 4717; shGFP, 3859) was significantly larger than that of the knockdown cells (sh#57, 2186; sh#58, 2305) (Figure 3E; Mixed Model ANOVA, p<0.001). Morphological differences were not observed in H1299 cells, which do not express endogenous collagen XXIII, that stably express control or collagen XXIII shRNA (Figure 3F&G). Moreover, in the presence of trypsin or non-enzymatic cell lifting solutions, H460 knockdown cell lines detached from tissue culture treated plates earlier than control cells, presumably due to their decreased adhesive capability.

Figure 3. Loss of collagen XXIII affects H460 cell morphology.

Shown are representative phase contrast micrographs of H460 A) pRS, B) shGFP, C) sh#57, and D) sh#58 cells as well as H1299 F) pRS and G) sh#57 cells 48 hours after initial seeding onto tissue culture treated dishes. H460 cells expressing shRNA against collagen XXIII exhibit an altered cellular morphology as compared to collagen XXIII-expressing cells. Knockdown cells generally appear more rounded than control cells and often exhibit delayed or absent spreading. Morphological changes are not observed between the H1299 control and knockdown clonal cell lines, which lack endogenous collagen XXIII. E) The surface area (pixels) of individual H460 control and knockdown cells from multiple phase micrographs was determined in triplicate using ImageJ software (Mixed Model ANOVA; *p<0.001).

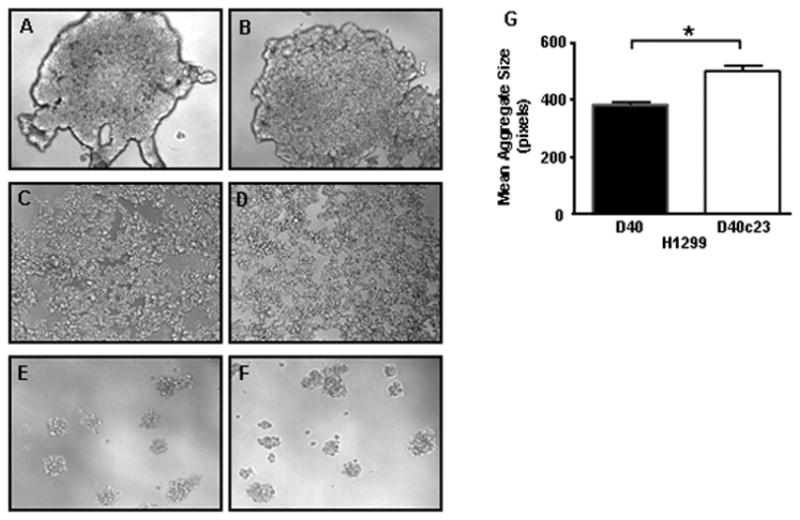

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on cell aggregation in suspension

Cell adhesion molecules can also facilitate homotypic cellular interactions. In an effort to examine collagen XXIII’s contribution to cell aggregation in suspension, H460 stable cell lines were grown for 24 hours in Costar ultra low adhesion plates. Microscopic analysis revealed differences in cell aggregate size and shape when comparing the control and collagen XXIII knockdown H460 cell lines (Figure 4A–D), but not the H1299 control and knockdown cell lines, which do not express endogenous collagen XXIII (Figure 4E&F). Specifically, control H460 cells formed large, tightly aggregated clumps, whereas H460 knockdown cell lines formed more loosely dispersed aggregates. Stable over-expression of human collagen XXIII in H1299 cells led to an increase in aggregate size (p<0.001) (Figure 4G), supporting the hypothesis that collagen XXIII aids homotypic cell adhesion.

Figure 4. Loss of collagen XXIII affects H460 cell aggregation in suspension.

H460 A) pRS, B) shGFP, C) sh#57 or D) sh#58 cells were seeded into plates coated with an ultra-low attachment surface (Corning) and cell aggregate density was visualized using light microscopy. Representative phase contrast micrographs depict differences in cell aggregation density between (A&B) collagen XXIII-expressing cells and (C&D) collagen XXIII knockdown cells. Representative phase contrast micrographs of aggregated H1299 E) pRS and F) sh#58 cells, which lack endogenous collagen XXIII, indicate similar aggregation densities 24 hours after seeding. G) In contrast, overexpression of collagen XXIII in H1299 cells (D40c23) resulted in larger cell aggregates than the control cell line (D40). Aggregate size was quantified by fluorescently labeling the aggregates 5 hours after seeding and determining the number of pixels per aggregate using Image J software (Mixed Model ANOVA; *p<0.001). Three or more independent experiments were performed in triplicate for each cell line.

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on cell adhesion to extracellular matrix molecules

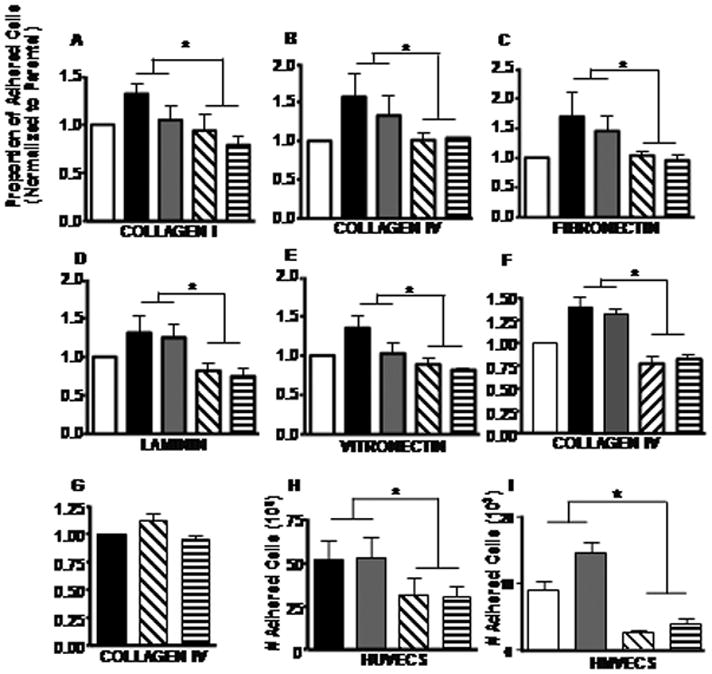

The role of collagen XXIII in cell-matrix adhesion was examined by analyzing H460 parental, control and knockdown cell line adhesion to tissue culture treated plates coated with different matrix molecules. Significant differences in cell adhesion on all matrices were observed when comparing the mean number of attached control and knockdown cells (Figure 5A–E and Supplemental Table 1). The results suggest a link between collagen XXIII protein level and adhesive ability to many different matrices.

Figure 5. Loss of collagen XXIII affects cell adhesion.

H460 parental (white) and H460 cells stably expressing control (pRS and shGFP; black and gray) or COL23A1 (sh#57 and sh#58; diagonal and horizontal stripes) shRNA were seeded in triplicate on tissue culture-treated 96 well plates coated with 5 μg/cm2 of A) collagen I, B) collagen IV, C) fibronectin, D) laminin or E) 1 μg/cm2 vitronectin and allowed to adhere for 1 hour. F) AT6.1 parental (white) cells and AT6.1 cells stably expressing control (GC2_6 and GC2_9; black and gray) or COL23A1 (1610_1 and 1610_2; diagonal and vertical stripes) miRNA and G) H1299 cells (which do not express detectable endogenous collagen XXIII) stably expressing control (pRS; black) or collagen XXIII shRNA (sh#57 and sh#58; diagonal and horizontal stripes) were seeded in plates coated with 5 μg/cm2 of collagen IV. For the cell-matrix adhesion experiments, unattached cells were removed with PBS and fluorescent cell labeling was used to determine the relative number of attached cells per well. Bars indicate the average proportion of adhered cells (after normalization to the parental or control cell line) ± SEM. Shown are the mean of three or more independent experiments performed in triplicate. H) H460 control and knockdown cell lines were seeded onto HUVEC monolayers and allowed to adhere for 40min. The number of adhered tumor cells was determined by comparing the total number of cells in wells containing either HUVECs alone or HUVECs and tumor cells. Shown are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. For all experiments, asterisks indicate a significant difference (*p<0.001) between the means of the control and knockdown cell lines as determined using mixed model ANOVA. I) H460 control and knockdown cell lines were seeded onto HMVEC monolayers as described for HUVEC. Shown are the mean number of adhered fluorescently labeled tumor cells from 4 data points ± SD. Cell number converted from a standard curve of labeled cells. Representative data shown from >4 independent experiments. For all experiments, asterisks indicate a significant difference (*p<0.001) between the means of the control and knockdown cell lines as determined using mixed model ANOVA.

Tissue culture treated plates promote non-specific cell adhesion. In an attempt to identify preferred matrix ligands, the cell adhesion experiments were repeated on non-tissue culture treated plates coated with matrix protein and blocked with albumin. In agreement with our previous cell adhesion data, the knockdown cell lines were less adherent to nearly all matrix molecules examined as compared to the control cell lines (Supplemental Figure 5A–E and Supplemental Table 2). Similar results were also seen when comparing AT6.1 cell lines stably expressing control (GC2_6 and GC2_9) or collagen XXIII (1610_1 and 1610_2) miRNA (Mixed Model ANOVA; p<0.001) (Figure 5F). To ensure that these effects were not due to off-target effects of the shRNA, control (pRS) or collagen XXIII (sh#57 or sh#58) shRNA constructs were stably expressed in H1299 cells, which lack detectable collagen XXIII. H1299 control and knockdown cells similarly adhered to collagen IV (Figure 5G), indicating that these shRNAs do not alter cell adhesion independently of collagen XXIII. In contrast, H1299 cells over-expressing collagen XXIII exhibit increased adhesive capability (Supplemental Figure 5F and Supplemental Table 3). Moreover, rescue of collagen XXIII expression in the H460 sh#57 and sh#58 cell lines also improved cell adhesion on collagen IV (Supplemental Figure 5G and Supplemental Table 3). These results reveal a clear correlation between collagen XXIII expression and cell adhesion to a variety of extracellular matrix components.

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on cell adhesion to endothelial cell monolayers

To examine whether collagen XXIII is also involved in heterotypic cell interactions, we measured H460 clonal cell adhesion to human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) monolayers. Of the cells initially seeded on HUVEC monolayers, 51% (pRS) or 52% (shGFP) of the control cells and 31% (sh#57) or 30% (sh#58) of the knockdown cells were able to adhere to the monolayers within 40 minutes (Mixed model ANOVA; p<0.001) (Figure 5H). Similar results were obtained when measuring H460 cell adhesion to HMVECs (Figure 5I). Microscopic examination of the co-cultured cells revealed H460 interactions both with the HUVECs and HMVECs and the exposed matrix deposited by the HUVEC cells—indicating that collagen XXIII mediates heterotypic cell interactions as well as cell-matrix interactions.

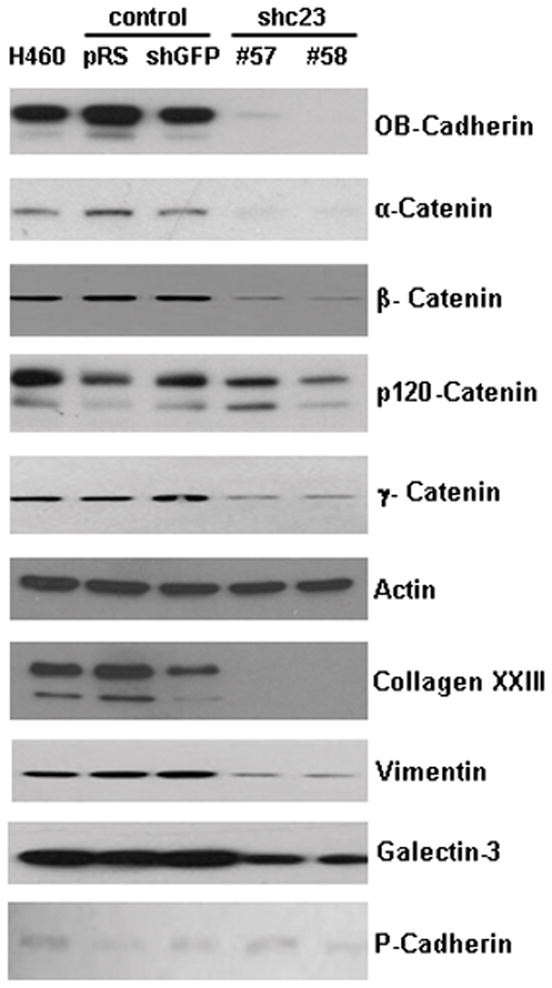

Loss of collagen XXIII: effects on protein expression

Stable repression of collagen XXIII resulted in cell rounding and decreased adhesive ability. Therefore, Western blot analysis was used to examine changes in other proteins with known roles in cell adhesion and structure. Our data shows that stable knockdown of collagen XXIII does not lead to reduced protein expression of integrin αV, α2, α5 or β1 nor with the expression of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Src, or ILK1, which can be modulated by integrins. Interestingly, one of the collagen XXIII knockdown clones showed a substantial reduction in integrin α6 expression (Supplemental Figure 6). More strikingly, stable repression of collagen XXIII led to decreased protein expression of cell adhesion complex proteins including OB-cadherin, β-catenin, α-catenin, and γ-catenin as well as vimentin and galectin-3 (Figure 6). E-cadherin and N-cadherin levels were undetectable in the control and knockdown cell lysates as revealed by Western blot. Analysis of total RNA in the control and knockdown cells revealed a reduction in OB-Cadherin RNA levels, but not α-, β-, δ- and γ-catenin (Supplemental Figure 7A). Furthermore, treatment of the knockdown cell lines with the proteasome inhibitors MG115 and MG132 stabilized β-, and γ-catenin protein levels (Supplemental Figure 7B). This indicates that collagen XXIII may regulate the expression or stability of certain cell adhesion molecules, thereby influencing the overall adhesive capacity of the cells.

Figure 6. shRNA-mediated silencing of collagen XXIII alters the expression of proteins involved in cell adhesion and structure.

Whole cell lysates were collected from H460 clonal cell lines and probed for various proteins involved in cell adhesion. In the knockdown cell lines, a reduction in OB-cadherin, gamma-, beta-, and alpha-catenin, vimentin and galectin-3 was observed. Analysis of the canonical cadherins revealed no changes in P-cadherin. E- and N-cadherin are not expressed in these cells. Actin was used as a loading control.

Discussion

Metastasis is responsible for the majority of cancer related deaths each year and much effort has focused on identifying the underlying genetic and proteomic alterations that drive this process. In this study, we demonstrate a correlation between collagen XXIII and increased lung metastasis in two in vivo models of metastasis—indicating that collagen XXIII enhances the metastatic potential of these cells. Mediators of metastasis can exhibit a broad spectrum of functionalities including adhesion, migration, proliferation and survival. Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are important mediators of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion. Certain cell adhesion molecules, including members of the integrin family such as α1β1, α2β1 and αvβ3, can interact with multiple matrix molecules (Barczyk et al 2010). Many CAMs exhibit altered protein expression in cancer cells and have known roles in metastasis (Schmidmaier and Baumann 2008). For example, in vivo metastasis of lung carcinoma cells is reduced by antibody-blocking of β1 integrin (Takenaka et al 2000) as well as RNAi-mediated knockdown of α5β1 integrin (Roman et al 2010). Relatedly, transmembrane collagens are known cell adhesion molecules, present in hemidesmosomes (collagen XVII) or focal adhesions (collagen XIII), and have diverse binding partners (Diaz et al 1990, Franzke et al 2003, Franzke et al 2005, Hagg et al 2001, Tu et al 2002, Veit et al 2007). Collagen XXIII has recently been shown to bind α2β1 integrin in keratinocytes (Veit et al 2011) and aids corneal epithelial cell binding to collagen IV and Matrigel (Gordon 2005).

Manipulation of collagen XXIII protein levels in cancer cell lines allowed us to determine whether collagen XXIII is necessary for different cellular functions and behaviors. Our results suggest that loss of collagen XXIII may globally impair cell adhesion—including cell-matrix adhesion, homotypic and heterotypic cell adhesion—and diminish cancer cell retention in the lung after hematogenous dissemination. These data make it possible to articulate more than one model for collagen XXIII function in metastasis. Collagen XXIII may facilitate cancer cell metastasis by mediating initial adhesion to the endothelium or exposed extracellular matrix, by promoting cancer cell aggregation within the blood vessels, or a combination of both. Similar functionalities have been observed with other proteins and are associated with increased metastasis formation. Increased galectin-3 and Thomsen Friendenreich antigen expression, for example, correlate with metastatic potential, and aid tumor cell adhesion to the endothelium (Khaldoyanidi et al 2003). These proteins also enhance homotypic cancer cell adhesion following initial heterotypic adhesion to the endothelium (Glinsky et al 2003, Khaldoyanidi et al 2003).

Anchorage-independent growth is a defining feature of cancer cells and correlates with metastatic potential (Cifone and Fidler 1980, Nomura et al 1989). Cell adhesion molecules can facilitate this process. Collagen XXIII expression is positively correlated with anchorage-independent growth of H460 cells. Changes in colony size and cell proliferation on tissue culture plates were not readily apparent; suggesting that collagen XXIII enhances colony formation efficiency without endowing cells with a proliferative advantage. Therefore, collagen XXIII may facilitate cell growth and survival when cancer cells are rounded and incapable of spreading. This property could be especially important when metastasizing cells reside temporarily within blood vessels.

Stable repression or over-expression of an individual protein can trigger additional proteomic changes within the cell. In some cases, these secondary changes are partially responsible for phenotypic and behavioral differences between clonal cell lines. Examination of proteomic changes in response to collagen XXIII knockdown revealed decreased protein expression of OB-cadherin, β-catenin, α-catenin, and γ-catenin, vimentin, galectin-3, and potentially α-6 integrin—each of which can affect cell morphology and adhesion.

H460 cells express high levels of OB-cadherin, which is normally expressed in osteoblasts and mesenchymal cells (Okazaki et al 1994, Simonneau et al 1995) and misexpressed in metastatic breast and prostate cancer cells (Bussemakers et al 2000, Chu et al 2008, Pishvaian et al 1999, Tomita et al 2000). OB-cadherin interacts with other cadherin molecules at the cell surface to form adherens junctions at sites of cell-cell contact, while the intracellular tail of OB-cadherin interacts with members of the catenin family (Pishvaian et al 1999). Though the link between collagen XXIII and OB-cadherin remains incompletely understood, others have shown that reducing OB-cadherin expression disrupts beta-catenin and gamma-catenin abundance (Di Benedetto et al 2010); potentially explaining why we observe a reduction in both OB-cadherin and catenin protein levels but only OB-cadherin RNA levels. A reduction in α6 integrin could also affect the adhesive and metastatic ability of the H460 collagen XXIII knockdown cells, as α6 integrin is important for cell adhesion on laminin and high α6 levels correlate with the metastatic phenotype in breast cancer cells (Mukhopadhyay et al 1999, Torimura et al 1999, Wewer et al 1997). Expression of either galectin-3 (Khaldoyanidi et al 2003) or the intermediate filament vimentin (Gilles et al 1996, Hu et al 2004) in carcinomas is also associated with metastasis.

Together, our results demonstrate a functional role for collagen XXIII in facilitating the formation of pulmonary metastases. This result is consistent with previous reports indicating that elevated collagen XXIII levels are associated with metastasis and with poor outcome in patients with prostate cancer and non-small cell carcinoma of the lung (Banyard et al 2007, Spivey et al 2010). We further provide a potential mechanism in which expression of collagen XXIII by tumor cells facilitates heterotypic adhesion to endothelium—a known requirement for tumor cell extravasation into distal organs (Miles et al 2008, Orr and Wang 2001). We also find that collagen XXIII mediates increased homotypic adhesion leading to increased cell aggregation, a phenomenon also reported to be associated with increased metastatic potential. These findings demonstrate that a transmembrane collagen can influence tumor metastasis in animals. Future studies will determine how this molecule could influence tumor aggressiveness and patient outcome in humans.

Methods

Cell culture, transfection, and immunoblot analysis

The H460 and H1299 (American Type Culture Collection) cells were cultured in recommended media and the AT6.1 cells (provided by J. Isaacs, Johns Hopkins University) were maintained as previously described (Isaacs et al 1986). For the proteasome inhibition experiments, knockdown cells (sh#57 and sh#58) were treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), carbobenzoxy-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-norvalinal (MG115), N-(benzyloxycarbonyl) leucinylleucinylleucinal (MG132) or N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-Nle-CHO (ALLN) (Sigma) prior to lysate collection. Whole cell lysates were collected using Triton Lysis Buffer or RIPA Buffer (Boston BioProducts) and supplemented with compete mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Diagnostics). Lysate protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Whole-cell lysates were resolved on Tris-HCl gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) and proteins were visualized using the ECL Plus chemiluminescence kit (Amersham). The antibodies used were mouse monoclonal antibodies to collagen XXIII, galectin-3 (R&D Systems), integrins α2, α3, α5, β3, β-catenin, p120-catenin, E, N, and P-Cadherin, FAK, pFAK397, (BD Biosciences), actin (Chemicon), vimentin (DAKO) and rabbit antibodies to ILK1, α-catenin, γ-catenin, OB-Cadherin, AKT, Src, pSrcY416, and integrins α4, αv, α6, β1, β4, β5 (Cell Signal).

Generation of stable cell lines

For knockdown studies, H460 or H1299 cells were transfected with an empty pRS vector, pRS encoding shRNA against collagen XXIII (sh#57 or sh#58) or pRS encoding ineffective shRNA against GFP (shGFP) (TR317712, Origene) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After selection in puromycin, clonal cell lines were established. Collagen XXIII expression was rescued by transfecting the sh#57 cell line with an empty pcDNA-DEST40 expression vector or pcDNA-DEST40COL23A1 or transfecting the sh#58 cell line with an empty pcDNA3 expression vector or pcDNA3-human collagen XXIIIR110A (mutated at the furin cleavage site) (Banyard et al 2007). Cells were pooled after selection in puromycin and Geneticin. H1299 cells were separately transfected with an empty pcDNA-DEST40 expression vector or pcDNA-DEST40COL23A1 and pooled cells were collected after selection in Geneticin. To generate pcDNA-DEST40COL23A1, collagen XXIII was PCR amplified from pcDNA3COL23A1 (Banyard et al 2007) vector using primers specific for the 5’ and 3’ end of the transcript, with the stop codon. It was ligated into pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and subcloned into pcDNA-DEST40 (Invitrogen). AT6.1 knockdown cells were made by transfection with the BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi vector, pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR (Invitrogen) containing sequence targeting rat collagen XXIII at position 1610 in accession number, AY158896. Insert sequence, 5’-GCTGACTCCTTTCCGACCAGGTAACTGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACAGTTCCTGCGGA AAGGAGTCAGG-3’. GFP-expressing stable cells were selected with blasticidin.

Statistical analysis

Mixed model ANOVA was used to assess significant changes in cell adhesion, aggregation or growth in soft agar between control and knockdown cell lines, taking account of random variation among replicate experiments. The mean of the knockdown cells was subtracted from the mean of the control cells and compared to zero. For each comparison, the p-value, if significant, is reported. One way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-test or a t-test were used to analyze the relationship between collagen XXIII status in H460 sublines and the number of spontaneous or experimental metastases formed in vivo as well as for experiments involving the H1299 cells. The analyses were performed by SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

Proliferation assays

1×104 cells were seeded into each well of a 96 well plate and allowed to grow for 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours. CyQUANT Reagent (Invitrogen) was used to fluorescently label cells. Average relative fluorescent units (RFU) were calculated for each set of replicates and fold change in RFU at each time point relative to RFU at 24 hours is reported.

Adhesion assays

96 well tissue culture (tc) treated plates were coated with 5 μg/cm2 human fibronectin, mouse laminin, mouse collagen IV (BD Biosciences), bovine collagen I (Cultrex), or 1 μg/cm2 human vitronectin (Millipore) for 1 hour, diluted according to the manufacture’s recommendations. Adhesion assays were also repeated on non-tc treated plates coated with each matrix molecule and blocked with a BSA solution for 1 hour. Cells were detached using EDTA solution (0.15g disodium EDTA, 4g NaCl, 0.28g sodium bicarbonate, 0.5g dextrose and 0.2g KCl dissolved in 500 ml water, sterile filtered) and 3×104 cells were allowed to adhere in each well for 1 hour at 37ºC in serum-free media. Plates were washed with PBS to remove any unattached cells and CyQUANT Reagent was used to fluorescently label adherent cells. Cell lines were also seeded onto HUVEC or HMVEC monolayers and allowed to adhere for 40min. The number of adhered tumor cells was determined by comparing the total number of cells in wells containing either endothelial cells alone or with tumor cells.

Soft agar assays

500 cells were suspended in 0.35% agar in complete RPMI and overlayed onto a 0.5% Agar in RPMI base. Colony formation efficiency was calculated using the following equation: (# of visible colonies after 12 days) / (# of cells originally seeded).

Immunofluorescence

H460 cells were seeded on collagen I-coated coverslips and incubated at 37ºC. Extensive DPBS washing was performed prior to fixation and between all subsequent steps unless otherwise noted. Cells were fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde for 2 minutes on ice followed by 10 minutes at room temperature. Unless cell surface staining was desired, cells were permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100/DPBS and blocked using 10% normal goat serum/DPBS with no subsequent DPBS wash. Following an hour incubation with the collagen XXIII clone 468642 (R&D systems) or γ-catenin (Cell Signal) antibodies at room temperature, the Alexa-488 or Alexa-568 conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) were added for 1 hour. Cells were mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen) and imaged using the appropriate filters. Cells were viewed using a Nikon Eclipse TE200 inverted light microscope and images acquired using the SPOT Insight imaging system (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc).

Cell aggregation assays

Adherent cells were detached using EDTA solution. Equal numbers of cells were plated into ultra low attachment plates (Costar) and grown in suspension for 5 to 96 hours. For the collagen XXIII overexpression cell lines, cell aggregates were labeled fluorescently using Calcein AM (Invitrogen) or CellTracker™ Green CMFDA (5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ImageJ software (NIH) analysis was used to determine the relative size (measured in pixels) of each aggregate.

PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the tissue culture cell lines using the RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using iScript (Bio-Rad). The resulting cDNA was amplified using Taq Polymerase (Takara) and primers specific for OB-Cadherin, collagen XXIII, β-catenin, δ-catenin, α-catenin, γ-catenin and GAPDH (RealTimePrimers). PCR products were visualized using gel electrophoresis.

Animal models

All animal experiments were performed under guidelines approved by the Children’s Hospital Boston Animal Care and Use Committee and Animal Resources Committee. For a spontaneous model of metastasis, 2×106 pRS or knockdown (sh#57 or sh#58) cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of 5–6 week old female SCID mice. Caliper measurements of the subcutaneous tumors were taken thrice weekly and tumor volume (length × width2) was calculated. Subcutaneous tumors were aseptically resected three weeks after cell inoculation. After three additional weeks, mice were sacrificed and the lungs were collected. Macroscopic surface metastases were counted followed by histological examination of serial lung sections. For all animal experiments, tissues were immediately fixed in 10% formalin.

For an experimental model of metastasis, 1×106 control or knockdown H460 cells were injected intravenously into 6 week female SCID mice. After approximately 30 days, mice were sacrificed and macroscopic lung metastases were counted prior to fixation in formalin. Paraffin-embedded serial lung sections were also histologically examined. To examine cancer cell adhesion to the lung at early time points, cell lines were fluorescently labeled with CellTracker™ Green CMFDA in vitro, according to the manufacture’s recommendation, and 2.5×106 cells were intravenously injected into 5–6 week female SCID mice. After 5 hours animals were anesthetized and euthanized. The lungs were perfused with 3mL PBS, mechanically digested and incubated in collagenase II solution (250 U/ml; Worthington). Cells were incubated with Red Blood Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma), filtered through a 40μm mesh filter and washed with HBSS between steps. The relative number of adhered cancer cells was determined using the FACSCalibur system. Gating was used to restrict analysis to 5×105 single viable cells per mouse. The proportion of adherent tumor cells within the mouse lung was determined (# fluorescently labeled cells/5×105 total cells).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jenny Mu for her assistance with the survival surgery performed in our spontaneous model of metastasis experiment. We also thank Colin Tasi for his assistance with the Western blots.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

B. Zetter is a consultant and has equity in Predictive Biosciences, which has licensed the rights to collagen XXIII when used as a cancer biomarker. K. Spivey, I. Chung, J. Banyard, I. Adini and H. Feldman declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website.

References

- Banyard J, Bao L, Zetter BR. Type XXIII Collagen, a New Transmembrane Collagen Identified in Metastatic Tumor Cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20989–20994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard J, Bao L, Hofer MD, Zurakowski D, Spivey KA, Feldman AS, et al. Collagen XXIII expression is associated with prostate cancer recurrence and distant metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2634–2642. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussemakers MJ, Van Bokhoven A, Tomita K, Jansen CF, Schalken JA. Complex cadherin expression in human prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K, Cheng CJ, Ye X, Lee YC, Zurita AJ, Chen DT, et al. Cadherin-11 promotes the metastasis of prostate cancer cells to bone. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1259–1267. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifone MA, Fidler IJ. Correlation of patterns of anchorage-independent growth with in vivo behavior of cells from a murine fibrosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:1039–1043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto A, Watkins M, Grimston S, Salazar V, Donsante C, Mbalaviele G, et al. N-cadherin and cadherin 11 modulate postnatal bone growth and osteoblast differentiation by distinct mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2640–2648. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz LA, Ratrie H, Saunders WS, Futamura S, Squiquera HL, Anhalt GJ, et al. Isolation of a human epidermal cDNA corresponding to the 180-kD autoantigen recognized by bullous pemphigoid and herpes gestationis sera. Immunolocalization of this protein to the hemidesmosome. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1088–1094. doi: 10.1172/JCI114812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell C, Bjork BF, Lilius L, Axelman K, Fabre SF, Fratiglioni L, et al. Genetic association to the amyloid plaque associated protein gene COL25A1 in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Tasanen K, Schacke H, Zhou Z, Tryggvason K, Mauch C, et al. Transmembrane collagen XVII, an epithelial adhesion protein, is shed from the cell surface by ADAMs. Embo J. 2002;21:5026–5035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Tasanen K, Schumann H, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Collagenous transmembrane proteins: collagen XVII as a prototype. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Tasanen K, Borradori L, Huotari V, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Shedding of collagen XVII/BP180: structural motifs influence cleavage from cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24521–24529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Bruckner P, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Collagenous transmembrane proteins: recent insights into biology and pathology. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4005–4008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Blobel CP. Shedding of collagen XVII/BP180 in skin depends on both ADAM10 and ADAM9. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23386–23396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles C, Polette M, Piette J, Delvigne AC, Thompson EW, Foidart JM, et al. Vimentin expression in cervical carcinomas: association with invasive and migratory potential. J Pathol. 1996;180:175–180. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199610)180:2<175::AID-PATH630>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinsky VV, Glinsky GV, Glinskii OV, Huxley VH, Turk JR, Mossine VV, et al. Intravascular metastatic cancer cell homotypic aggregation at the sites of primary attachment to the endothelium. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3805–3811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MBP, Song R, Hahn RA, Shakarjian M, Gerecke DR, Koch M. Collagen XXIII Facilitates Adhesion of Corneal Epithelial Cells to Type IV Collagen and Matrigel. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Hagg P, Vaisanen T, Tuomisto A, Rehn M, Tu H, Huhtala P, et al. Type XIII collagen: a novel cell adhesion component present in a range of cell-matrix adhesions and in the intercalated discs between cardiac muscle cells. Matrix Biol. 2001;19:727–742. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Wakabayashi T, Watanabe A, Kowa H, Hosoda R, Nakamura A, et al. CLAC: a novel Alzheimer amyloid plaque component derived from a transmembrane precursor, CLAC-P/collagen type XXV. Embo J. 2002;21:1524–1534. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Lau SH, Tzang CH, Wen JM, Wang W, Xie D, et al. Association of Vimentin overexpression and hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Oncogene. 2004;23:298–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JT, Isaacs WB, Feitz WF, Scheres J. Establishment and characterization of seven Dunning rat prostatic cancer cell lines and their use in developing methods for predicting metastatic abilities of prostatic cancers. Prostate. 1986;9:261–281. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuyama H, Soderberg L, Horigome K, Winblad B, Dahlqvist C, Naslund J, et al. CLAC binds to aggregated Abeta and Abeta fragments, and attenuates fibril elongation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15602–15609. doi: 10.1021/bi051263e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldoyanidi SK, Glinsky VV, Sikora L, Glinskii AB, Mossine VV, Quinn TP, et al. MDA-MB-435 human breast carcinoma cell homo- and heterotypic adhesion under flow conditions is mediated in part by Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen-galectin-3 interactions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4127–4134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvist AP, Latvanlehto A, Sund M, Eklund L, Vaisanen T, Hagg P, et al. Lack of cytosolic and transmembrane domains of type XIII collagen results in progressive myopathy. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1581–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62542-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles FL, Pruitt FL, van Golen KL, Cooper CR. Stepping out of the flow: capillary extravasation in cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:305–324. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Theriault RL, Price JE. Increased levels of alpha6 integrins are associated with the metastatic phenotype of human breast cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:325–332. doi: 10.1023/a:1006659230585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y, Tashiro H, Hisamatsu K. In vitro clonogenic growth and metastatic potential of human operable breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5288–5293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki M, Takeshita S, Kawai S, Kikuno R, Tsujimura A, Kudo A, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of OB-cadherin, a new member of cadherin family expressed in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12092–12098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr FW, Wang HH. Tumor cell interactions with the microvasculature: a rate-limiting step in metastasis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10:357–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada Y, Hashimoto T, Nishimura A, Matsuo Y, Wakabayashi T, Iwatsubo T. CLAC binds to amyloid beta peptides through the positively charged amino acid cluster within the collagenous domain 1 and inhibits formation of amyloid fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8596–8605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajaniemi T, Tamminen M. The alpha 1 chain of type XIII collagen consists of three collagenous and four noncollagenous domains, and its primary transcript undergoes complex alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16922–16928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishvaian MJ, Feltes CM, Thompson P, Bussemakers MJ, Schalken JA, Byers SW. Cadherin-11 is expressed in invasive breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:947–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman J, Ritzenthaler JD, Roser-Page S, Sun X, Han S. {alpha}5{beta}1 Integrin Expression is Essential for Tumor Progression in Experimental Lung Cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0375OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidmaier R, Baumann P. ANTI-ADHESION evolves to a promising therapeutic concept in oncology. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:978–990. doi: 10.2174/092986708784049667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonneau L, Kitagawa M, Suzuki S, Thiery JP. Cadherin 11 expression marks the mesenchymal phenotype: towards new functions for cadherins? Cell Adhes Commun. 1995;3:115–130. doi: 10.3109/15419069509081281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg L, Dahlqvist C, Kakuyama H, Thyberg J, Ito A, Winblad B, et al. Collagenous Alzheimer amyloid plaque component assembles amyloid fibrils into protease resistant aggregates. FEBS J. 2005;272:2231–2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivey KA, Banyard J, Solis LM, Wistuba, Barletta JA, Gandhi L, et al. Collagen XXIII: a potential biomarker for the detection of primary and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1362–1372. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka K, Shibuya M, Takeda Y, Hibino S, Gemma A, Ono Y, et al. Altered expression and function of beta1 integrins in a highly metastatic human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:1187–1194. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.6.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K, van Bokhoven A, van Leenders GJ, Ruijter ET, Jansen CF, Bussemakers MJ, et al. Cadherin switching in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3650–3654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Xu Y, Scearce-Levie K, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. COL25A1 triggers and promotes Alzheimer's disease-like pathology in vivo. Neurogenetics. 2010;11:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0201-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torimura T, Ueno T, Kin M, Ogata R, Inuzuka S, Sugawara H, et al. Integrin alpha6beta1 plays a significant role in the attachment of hepatoma cells to laminin. J Hepatol. 1999;31:734–740. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H, Sasaki T, Snellman A, Gohring W, Pirila P, Timpl R, et al. The type XIII collagen ectodomain is a 150-nm rod and capable of binding to fibronectin, nidogen-2, perlecan, and heparin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23092–23099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisanen MR, Vaisanen T, Pihlajaniemi T. The shed ectodomain of type XIII collagen affects cell behaviour in a matrix-dependent manner. Biochem J. 2004;380:685–693. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisanen T, Vaisanen MR, Autio-Harmainen H, Pihlajaniemi T. Type XIII collagen expression is induced during malignant transformation in various epithelial and mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2005;207:324–335. doi: 10.1002/path.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit G, Zimina EP, Franzke CW, Kutsch S, Siebolds U, Gordon MK, et al. Shedding of collagen XXIII is mediated by furin and depends on the plasma membrane microenvironment. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27424–27435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit G, Zwolanek D, Eckes B, Niland S, Käpylä, Zweers MC, Ishada-Yamamoto A, Krieg T, Heino J, Eble JA, Koch M. Collagen XXIII - novel ligand for integrin α2β1 in the epidermis. J Biol Chem. 2011 Jun 7; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220046. Epub adhead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewer UM, Shaw LM, Albrechtsen R, Mercurio AM. The integrin alpha 6 beta 1 promotes the survival of metastatic human breast carcinoma cells in mice. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1191–1198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.