Abstract

As a potentially viable method of brain drug delivery, the safety profile of blood-brain barrier (BBB) opening using focused ultrasound (FUS) and ultrasound contrast agents (UCA) needs to be established. In this study, we provide a short-term (30 min or 5h survival) histological assessment of murine brains undergoing FUS-induced BBB opening. Forty-nine mice were intravenously injected with Definity® microbubbles (0.05 μl/kg) and sonicated under the following parameters: frequency of 1.525 MHz, burst length of 20 ms, PRF of 10 Hz, peak rarefactional acoustic pressures of 0.15-0.98 MPa, and two 30-s sonication intervals with an intermittent 30-s delay. The BBB opening threshold was found to be 0.15-0.3 MPa based on fluorescence and MR imaging of systemically-injected tracers. Analysis of three histological measures in H&E-stained sections revealed the safest acoustic pressure to be within the range of 0.3-0.46 MPa in all examined time periods post sonication. Across different pressure amplitudes, only the samples 30 min post-opening showed significant difference (p<0.05) in the average number of distinct damaged sites, microvacuolated sites, dark neurons, and sites with extravasated erythrocytes. Enhanced fluorescence around severed microvessels was also noted and found to be associated with the largest tissue effects while mildly diffuse BBB opening with uniform fluorescence in the parenchyma was associated with no or mild tissue injury. Region-specific areas of the sonicated brain (thalamus, hippocampal fissure, dentate gyrus, and CA3 area of hippocampus) exhibited variation in fluorescence intensity based on the position, orientation, and size of affected vessels. The results of this short-term histological analysis demonstrated the feasibility of a safe FUS-UCA-induced BBB opening under a specific set of sonication parameters and provided new insights on the mechanism of BBB opening.

Keywords: Blood-Brain Barrier Opening, Focused Ultrasound, Definity Microbubbles, Hippocampus, Safety Assessment, Histological Damage

INTRODUCTION

Effective delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain has been mainly hindered by the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is a complex regulatory system within the neurovascular unit that maintains brain homeostasis by controlling the flow of nutrients and chemicals into and out of the brain parenchyma (Abbott et al., 2006). Lipid solubility, molecular size, and charge are some of the determining factors for the passage of molecules across the BBB (Habgood et al., 2000). Based on these criteria, at least two types of permeability barriers exist at the BBB: 1) a physical paracellular barrier at the tight junctions (TJ) of the endothelial cells that prevents the passage of molecules (>180 Da) through the interendothelial clefts (Kroll and Neuwelt, 1998), and 2) a chemically-selective transcellular barrier at the plasma membrane of endothelial cells that controls molecular transport by utilizing carrier-mediated, receptor-mediated, and active efflux transporters, as well as endocytotic vesicular pathways (Zlokovic, 2008). Thus, an effective delivery of pharmacological agents to the brain requires successful passage across at least one of these two barriers.

Despite some limited success, currently available drug delivery methods fail to simultaneously satisfy two desirable outcomes: a localized delivery and a noninvasive procedure. One example is the intra-arterial injection of hyperosmotic solutions such as mannitol (Kroll and Neuwelt, 1998; Lossinsky et al., 1995; Rapoport, 1996) that causes the shrinkage of endothelial cells and provides a paracellular passage for the drug. Another method is the chemical modification of drugs by lipidization or conjugation to genetically-engineered molecular Trojan horses, promoting transcellular passage via lipid-mediated diffusion or receptor-mediated transport, respectively (Fischer et al., 1998; Pardridge, 2002; Pardridge, 2005). Both of these methods are noninvasive, but they cause diffuse BBB opening and undesirable drug distribution to non-targeted areas of the brain. Other approaches such as convection-enhanced diffusion and intracranial injection (Bobo et al., 1994; Weaver and Laske, 2003) provide a more localized delivery of the drug, but involve an invasive neurosurgical operation that may lead to hemorrhage, inflammation, and neuronal damage.

An ideal drug delivery method to the brain would require a localized and temporary disruption of the BBB with minimal damage to the surrounding tissue. Multiple studies have shown that focused ultrasound (FUS) can open the BBB in the central nervous system (CNS) (Bakay et al., 1956; Ballantine et al., 1956; Mesiwala et al., 2002). In recent years, researchers have utilized FUS in conjunction with ultrasound contrast agents (UCA, pre-formed microbubbles) to disrupt the BBB locally, non-invasively, and transiently (Hynynen et al., 2001; Choi et al., 2007b; Hynynen 2008). Our group along with others has shown feasibility of transcranial FUS application with successful BBB opening at the targeted region in wild-type and transgenic mice (Choi et al., 2007b; Choi et al., 2008), and in larger animal models such as rats, rabbits and pigs (Hynynen et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2007). In addition, molecular delivery of several tracer compounds and therapeutic agents into the brain have been shown and studied, including dextrans (Choi et al., 2010a; Wang et al., 2008), gadolinium (Choi et al., 2007a; Hynynen et al., 2001), horseradish peroxidase (Hynynen et al., 2005), immunoglobulin G (Sheikov et al., 2004), Herceptin (Kinoshita et al., 2006a), doxorubicin (Treat et al., 2007), anti-amyloid antibody (Raymond et al., 2008), and dopamine D4 receptor antibody (Kinoshita et al., 2006b).

Although the exact mechanism of BBB opening remains to be determined, the interaction of the ultrasound beam with microbubbles results in mechanical changes in the microvasculature and thereby changes in the integrity of the BBB components. Previous studies suggest that both paracellular and transcellular barriers are affected during and after FUS-UCA interaction (Sheikov et al., 2004). There is evidence that a redistribution and loss of immunosignals at the TJ proteins (such as occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1) occurs up to four hours following the sonication. Moreover, the vesicular transport of tracer molecules across the endothelial cells increases, contributing to further penetration of these molecules into the basement membrane, surrounding pericytes, arteriole smooth muscle cells, and perivascular neuropil (Sheikov et al., 2008). While these changes in BBB integrity are reversible under the conditions of the aforementioned studies, the damaging impact of such anatomical and physiological modification remains to be thoroughly assessed.

Under specific sonication parameters, recent safety studies by some groups have shown BBB disruption with minimal or negligible damage to the vasculature and the surrounding tissue (Hynynen et al., 2005; Hynynen et al., 2006; McDannold et al., 2007; McDannold et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2007). While it is difficult to make accurate comparisons among different studies because of the subjective nature of histological assessment and variations in experimental parameters and procedures, some broad conclusions can be summarized from previously reported findings. So far, short-term and long-term assessments have been performed on animals (mice, rats, and rabbits) sacrificed four hours to four weeks after sonication. Generally, lower frequency focused ultrasound along with lower pressure amplitudes and lower UCA doses have been shown to result in reduced tissue injury (Hynynen et al., 2005; Hynynen et al., 2006; McDannold et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007). The histological damage has been mostly limited to few isolated or clusters of red blood cell (RBC) extravasations and few apoptotic neurons. While a few studies have attempted to associate certain sonication parameters with specific microscopic damage (McDannold et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2007), additional safety studies are warranted to investigate optimal sonication parameters that result in the delivery of clinically-relevant doses of therapeutic agents with no or minimal associated bioeffects.

In this study, we aim at adding new information to the existing reports on the safety of the FUS-UCA interaction using a different combination of values for sonication parameters (frequency: 1.525 MHz, burst length: 20 ms, PRF: 10 Hz, duration: two 30s sonication intervals with 30s delay in between, peak-negative pressures of 0.3-0.98 MPa) with Definity® microbubbles. Under these conditions, we will 1) assess the safety profile of the technique more comprehensively by evaluating and quantifying three histological criteria and one composite measure of damage, 2) describe short-term effects of the procedure on mice sacrificed 30 min or five hours after sonication, 3) characterize the relationship between BBB disruption and tissue injury to identify any correlation between highly concentrated fluorescence (detected in previous studies) and neurovascular damage, and 4) determine variability in BBB opening and microscopic damage in region-specific areas of the brain such as the hippocampus and the thalamus.

Our experiments are also unique with respect to the ease of comparison to the control un-sonicated region (right hippocampus) and perhaps in offering a greater objectivity in assessing BBB opening and histological damage. The unique shape of the hippocampus along with the nearby ventricles, the rich distribution of the vasculature in the hippocampal formation, the unique arrangement of neuronal cell bodies in pyramidal and granular layers of the hippocampus, and the symmetric position of the right and left hippocampi in horizontal sections all contribute to the useful characteristics of the hippocampal region as a targeted area. Our results provide new insights on the mechanism and safety of BBB opening while reinforcing previous findings, i.e., that using an appropriate combination of sonication parameters can result in BBB opening with no or negligible tissue effects within a short time period following the sonication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Animals and Anesthesia

All animal procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 52 adult male mice were used for this study (CB57L/6 strain, 18-31 g, Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The animals were anesthetized with a mixture of oxygen (0.8 L/min at 1.0 Bar, 21°C) and 1.5-2.0% vaporized isoflurane (Aerrane, Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) using an anesthesia vaporizer (Model 100 Vaporizer, SurgiVet, Inc. Waukesha, WI, USA). The mouse's vital signs were continuously monitored (Respiration rate: 50-80 per min) and isoflurane was adjusted throughout the experiment as needed. The mouse was kept warm using an infrared heat lamp at all times.

2. Ultrasound Setup

A single-element circular-aperture FUS transducer (center frequency: 1.525 MHz; focal depth: 90 mm; outer radius: 30 mm; inner radius 11.2 mm) with a pulse-echo transducer in its center was used for sonication (Choi et al., 2007b). A single-element, pulse-echo transducer (center frequency: 7.5 MHz) with a focal length of 60 mm was positioned through the center hole of the FUS transducer so that the foci of the two transducers could be properly aligned. The pulse-echo transducer was driven by a pulser-receiver system (Model 5800, Panametrics, Waltham, MA, USA) connected to a digitizer (CS8349, Gage Applied Technologies, Inc., Lachine, QC, Canada). A cone filled with degassed and distilled water and capped with an ultra-thin polyurethane membrane with ultrasound transparency (Trojan; Church & Dwight Co., Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) was mounted on the transducer system (Fig. 1a).

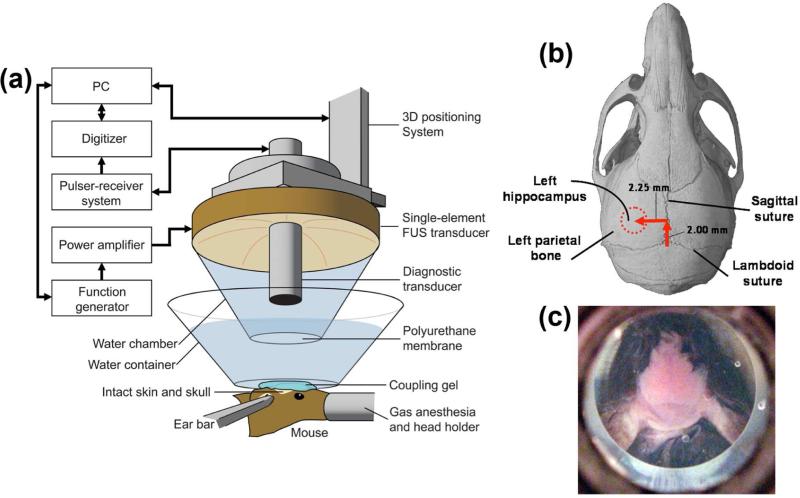

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental setup, (b) location sites of FUS-targeted regions in vivo (dotted lines), and (c) Identification of skull sutures (saggital and lambdoid) after a small water container was suspended over the mouse's head.

The FUS transducer was attached to a computer-controlled 3-D positioning system (Velmex Inc., Lachine, QC, Canada) and was driven by a function generator (3320A, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) through a 50-dB power amplifier (325LA, ENI Inc., Rochester, NY, USA).

As previously described (Choi et al., 2007b), the acoustic pressure of the FUS transducer was measured with a needle hydrophone (HP Series, Precision Acoustics Ltd., Dorchester, Dorset, UK; needle diameter: 0.2 mm) in a water-tank filled with degassed water. The obtained values were then corrected using the attenuation values of the skull (Choi et al., 2007b). As determined in that study, the mouse skull attenuated the acoustic pressure by 18.1±1.5% (n=5) through the parietal bone. The dimensions of the beam were measured to have a lateral and axial full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) intensity of approximately 1.32 and 13.0 mm, respectively.

3. Targeting Procedure

Anesthetized mice were placed prone on a bed and their heads were immobilized using a stereotaxic frame. The fur on the head was removed with an electric razor and a depilatory cream. A small container was filled with degassed and distilled water and suspended over the mouse's head (Fig. 1c). The bottom part of the container consisted of a thin plastic membrane that was acoustically and optically transparent (Saran; SC Johnson, Racine, WI, USA). Ultrasound gel was then used to couple the thin plastic membrane with the mouse skin (Fig. 1a).

We used a grid positioning method to target the mouse hippocampus (Choi et al. 2007b). For this purpose, the sutures of the mouse skull were identified and used as anatomic landmarks (Fig. 1c). The location of the hippocampus relative to the sutures was identified based on the known mouse brain and skull anatomy. A grid was constructed from three 0.3 mm thin metal bars. Two of them were placed parallel to each other and separated by 4 mm, and the third bar was soldered perpendicular to the other two through their center plane (Choi et al., 2007b). The grid was placed at the bottom of the water container, on top of the skull, and in alignment with the sutures visible through the skin (Fig. 1c). The center bar was aligned along the sagittal suture while one of the parallel bars was in alignment with the lambdoid suture. Utilizing the pulse-echo transducer, a lateral two-dimensional raster-scan of the grid was generated. The transducer's beam axis was then positioned 2.25 and 2 mm away from the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, respectively (Fig. 1b). Finally, the focal point was placed 3 mm beneath the top of the skull so that the acoustic wave propagated through the left parietal bone and overlapped with the left hippocampus and a small portion of the lateral region of the thalamus. Using this grid-positioning system, precise and reproducible targeting of the hippocampus of the murine brain was performed (Choi et al., 2007b).

4. Microbubbles Injection and Sonication

For each series of experiments performed on the same day, a new vial of Definity® microbubbles (Bristol-Myers Squibb Medical Imaging Inc., North Billerica, Massachusetts) was first activated using the manufacturer's instructions. Definity® microbubbles are composed of octafluoropropane gas encapsulated in a lipid shell, with a reported diameter of 1.1-3.3 μm and mean concentration of 1.2 × 1010 bubbles per mL. After activation, a 1:20 dilution of Definity was prepared using 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then injected immediately into the tail vein (50μl of original concentration per kilogram of mouse body mass). The targeted left hippocampus was then sonicated one minute later using the pulsed-wave FUS (burst rate: 10 Hz; burst duration: 20 ms; duty cycle: 20%) in two 30s sonication intervals with an intermittent 30s delay. The one-minute delay between the microbubbles injection and sonication was selected for consistency with our previous experiments. Initially, the reason was to allow the microbubbles to circulate more homogeneously in the blood stream rather than being concentrated in one region and diluted in another. The 30s pause between the two sonications was to allow the dissipation of the generated heat from the first sonication. Peak rarefactional acoustic pressures of 0.15, 0.30, 0.46, 0.61, 0.75, 0.90, and 0.98 MPa were used. The right hippocampus was not targeted and was used as the control. We examined the presence and the extent of BBB opening at the sonicated location using the injected fluorescent-tagged dextrans (n=28) or MRI contrast agent gadolinium (n=17)(see below).

5. MRI

Each mouse (n=17) was immobilized in a 3.8-cm-diameter birdcage coil and inserted in a vertical bore 9.4-Tesla MR system (DPX400, Bruker Medical, Boston, MA, USA). 1-2% isoflurane was administered while the respiration rate of the mouse was monitored throughout the procedure. About 90 minutes post-sonication (delay due to transportation and setup time), in vivo T1-weighted horizontal images of the mouse brain were then sequentially acquired (TR/TE: 246.1 ms / 10 ms, Bandwidth: 50,505.1 Hz Number of Excitations: 5, matrix size: 256 × 256, Field of View: 1.92 × 2.14 cm, slice thickness: 0.6 mm) before (3 images, duration: 12 min) and after (21 images, duration: 90 min) injection of an MRI contrast agent. The agent was a gadolinium-based, BBB-impermeable compound (Omniscan, Amersham Health, AS Oslo, NOR, amount: 0.75 ml, molecular weight: 573.7 Da) and was administered intra-peritoneally (IP) via a catheter to depict the BBB opening. IP injection allowed for the slow uptake of the MRI contrast agent into the bloodstream, and hence made it more amenable to the low MR temporal resolution. MRI images used in this study are from ~150 min post sonication (~60 min post gadolinium injection) and they correspond to peaking of the MR intensity as determined by our previous studies (Choi et al. 2007a; Choi et al. 2007b).

6. Tracer Injection and Perfusion

In order to determine the actual sonicated location and to verify BBB opening at the targeted region, a bolus injection of 3 kDa lysine-fixable Texas Red (TR) dextrans (Molecular Probes Inc.; Eugene, OR, USA) was followed 10 minutes after sonication (n=28). The tracer was dissolved in 1x PBS (0.2 ml) to a final concentration of 80 mg/kg of mouse body mass and injected into the femoral vein. A circulation time of either 30 minutes (n=13) or five hours (n=15, five out of which MRI was used to confirm the opening) was allowed depending on the experiment. The total number of studied sections per brain was 24 in the control (0 MPa) and 56 in the sonicated cases (0.3-0.75 MPa). The animals were subsequently sacrificed and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (4-5 min.) and 4% paraformaldehyde (7-8 min) at a flow rate of 6.8 ml/min. Next, the skull was removed and the brain was immersion-fixed for 24 hours before extracting the brain. The brain was fixed again in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48-120 hours prior to sectioning.

7. Histology and Microscopy

For microscopic evaluation, the post-fixation processing of the brain tissue was performed according to standard histological procedures. The paraffin-embedded specimen was sectioned horizontally at 6-μm-thickness in 12 separate levels that covered most of the hippocampus. To reach the targeted hippocampal formation, 1.2 mm from the top of the brain was trimmed away and discarded. At this first level, six sections were acquired, spanning over 36 μm of brain tissue. Another 80 μm of tissue were discarded and the process was repeated for another 11 levels, totaling 72 sections. For each level, the first two sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) while four other unstained sections were used for fluorescence imaging of Texas-Red (TR) dextrans and for additional future staining and assays. Bright-field and fluorescence images were acquired using two microscopes (BX61 and IX-81; Olympus, Melville, NY, USA) that provided both light and fluorescence imaging, with a filter set at excitation and emission wavelengths of 595 nm and 615 nm, respectively.

8. Determining BBB Opening Threshold

Occurrence of the BBB opening was assumed when associated with fluorescence or contrast enhancement at the targeted site (left hippocampus) compared to the control (right hippocampus). Only sonicated hippocampi with a clear diffusion of the tracer compound into the parenchyma were considered to have undergone BBB opening. Hence, a greater amount of fluorescence in the arterioles or larger vessels was insufficient in confirming BBB opening. The threshold for opening was determined as the lowest peak negative pressure, which resulted in BBB opening in over 50% of the sonicated samples.

9. Safety Assessment: Gross Examination

In order to identify and exclude easily evident, damage-inducing pressures from future consideration, a gross examination was performed on the brains of four mice prior to the study (sonicated with acoustic pressures of 0.46, 0.61, 0.75, and 0.98 MPa). Brains were sectioned horizontally into three slices (~1.7 mm each) and examined for detectable hemorrhage under a low-power microscope. Only pressures that did not result in large-scale hemorrhage were selected for microscopic examination.

10. Safety Assessment: Microscopic Evaluation

H&E-stained thin brain sections from samples sonicated with acoustic pressures of 0.30 MPa (n=7), 0.46 MPa (n=7), 0.61 MPa (n=7), and 0.75 MPa (n=7) were analyzed under the same bright-field microscope for histological damage. H&E sections from three control brains (no microbubble injection and/or no sonication) were also evaluated. Prior to the evaluation, adjacent unstained sections (6 μm) were examined under fluorescence microscopy to confirm the presence and extent of the opening at the sonicated location. BBB-opened regions were identified and all 24 H&E sections from the 12 levels were examined accordingly to search for abnormal tissue. For quantification, in the case of each brain, eight sections from eight different levels showing the greatest amount of damage were selected (covering 0.85 mm of hippocampus) and three histological measures were evaluated. The number of dark neurons, number of sites with more than five RBC extravasations, and the number and total area of microvacuolations were counted and calculated for the left (sonicated) and the right control hippocampus in each section. Furthermore, the number of distinct damaged sites (DDS) as a total and composite measure of histological damage per section was also determined in both the left and right hippocampi. For each histological measure, the values obtained from eight sections were added together and a net difference was calculated as the sum of values from left hippocampus subtracted from the sum of values in the right hippocampus. The net difference values were averaged across all brains and then plotted, comparing damage at different pressure amplitudes (0.30-0.75 MPa) and at two different survival periods (30 min and 5 h). A Student's t-test was used to determine significant difference. A p-value of p<0.05 was considered significant in all comparisons. One distinct damaged site was defined as a discrete area of microvacuolation with well-defined borders, a localized region containing more than five damaged neurons, or an extravascular region containing localized extravasations of more than five erythrocytes. A combination of any two or more of the mentioned histological measures at one localized region would also constitute one distinct damaged site. Damaged neurons were identified based on characteristics of dark neurons in H&E-stained sections. These neurons had shrunken and triangulated cell bodies, eosinophilic perikaryal cytoplasm, and pyknotic basophilic nuclei. In our assessment, the right hippocampus served as the baseline, so its general appearance was taken into account when the left hippocampus was analyzed microscopically, accounting for any artifacts or general poor tissue quality that could have happened due to inadequate fixation, poor tissue handling or processing, or because of the experimental procedure itself. As an example, this methodology accounted for the arbitrary decision to count only the sites with five or more extravasated red blood cells. Generally, extravasations of less than five RBCs in most samples were infrequent and often required a greater amount of time analyzing the sections. In poorly perfused brains however, detection of small number of RBCs in different regions was relatively easier and more troublesome, since poor saline perfusion could introduce RBC counting errors. In these brains, RBCs could be detected in small numbers not only in the sonicated region, but also inside and around many microvessels in other regions of the brain. Tissue processing and the plane of sectioning could distort the data count by presenting those few RBCs outside the vessels (which were actually inside). Such artifact was factored in and only regions with greater than five extravasated RBCs were counted, which most often correlated with the sonication at the left hippocampus. We also applied extra care to avoid the “dark neuron artifact” as described by Cammermeyer and others (Cammermeyer, 1960; Cammermeyer, 1978; Jortner, 2005), caused by post-mortem trauma as a result of inadequate perfusion fixation or improper tissue handling. Safety analysis was performed by the same trained observer to avoid inconsistency and to reduce assessment error.

Finally, a side-by-side analysis of adjacent unstained and H&E-stained sections was carried out to better understand the mechanism of blood-brain barrier opening and induced histological damage. First, florescence microscopy of unstained sections was performed to provide information on the characteristics of BBB opening based on diffusion of TR-dextrans into the brain parenchyma. Then, adjacent to the unstained sections, within a 6-80 μm distance, H&E-stained sections were analyzed for any type of damage, especially at the sites of BBB opening detected in unstained sections.

RESULTS 1. BBB Opening Threshold

BBB opening occurrence was investigated in brains injected with different tracers such as fluorescent-tagged dextrans (Figs. 2a and 2e) and Gadolinium (Figs. 2c, 2g, and 2j). The threshold for opening was determined as the minimum peak-rarefactional pressure beyond which 50% opening of the sonicated samples experienced opening. Table 1 shows the percent occurrence of BBB opening in 49 sonicated samples within the acoustic pressure range of 0.15-0.98 MPa. For the lowest acoustic pressure tested (0.15 MPa), there was absence of tracer diffusion in the sonicated regions and therefore no BBB opening occurred (Fig. 2i). The next tested pressure (0.30 MPa) resulted in BBB opening at a yield of 70% (Fig. 2c and 2j). Based on these findings, we have determined the pressure threshold for BBB opening to be within the range of 0.15-0.30 MPa under the conditions used in our study.

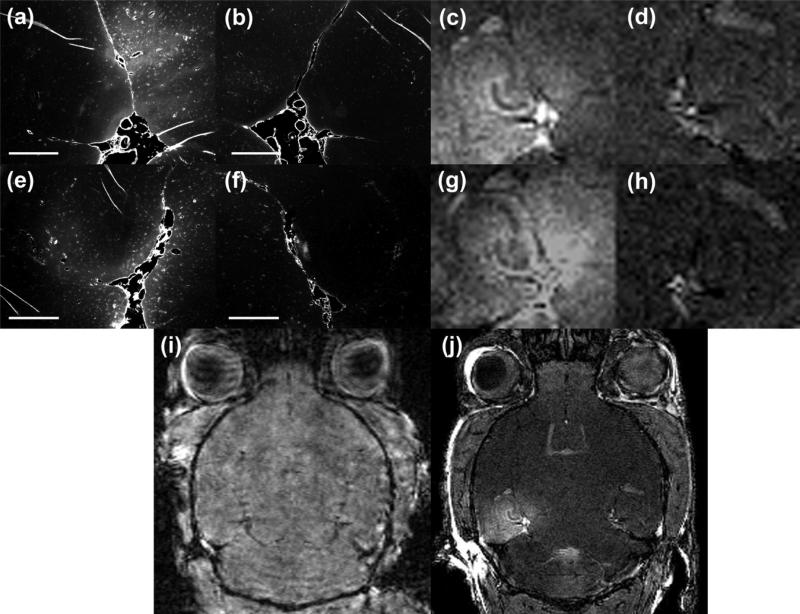

Figure 2.

Fluorescent and MRI images of five brains sonicated at 0.15 MPa (i), 0.30 MPa (a, c, j) and 0.46 MPa (e and g) acoustic pressures. Images in (c-d) are zoomed in and cropped versions of the image in (j). In case of 0.30 and 0.46 MPa, the right hippocampus was not sonicated and served as the control for the sonicated regions, respectively (b, d, f, and h). In case of 0.15 MPa, the right hippocampus was sonicated and the left side served as control. BBB opening was only detectable in mice sonicated at 0.30 MPa and above. In (a-b and e-f), the fluorescent tracer used was a 3-kDa Texas Red dextran and the mice were sacrificed 30 min after sonication. In (c-d, g-j), gadolinium was used as the MRI contrast agent and the mice were sacrificed 5 h after sonication. Magnification in (a-b and e-f) is 40x. Scale bar: 500 μm.

Table 1.

Percent BBB disruption in all studied brain samples sonicated at various acoustic pressures (0.15-0.9 MPa).

| Pressure amplitude (MPa) | Number of samples studied (n) | Number of samples with BBB opening (n) | % of samples with BBB opening |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.15 | 3 | 0 | 0% |

| 0.30 | 10 | 7 | 70% |

| 0.46 | 13 | 10 | 77% |

| 0.61 | 10 | 9 | 90% |

| 0.75 | 11 | 11 | 100% |

| 0.90 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

2. Safety Profile and Histology Assessment at Different Survival Periods

2.1. Gross Examination

The gross examination of four brain samples (0.46, 0.61, 0.75, and 0.98 MPa; sacrificed 30 min after sonication) indicated that a peak negative pressure of 0.98 MPa resulted in large-scale hemorrhage and extensive tissue damage. Patches of hemorrhage were evident in several locations in the sonicated region (left hippocampus; Fig. 3d), whereas no hemorrhage was present in the un-sonicated right hippocampus. In contrast, samples sonicated at the acoustic pressures of 0.46, 0.61, and 0.75 MPa showed no detectable hemorrhage (Figs. 3a-b). Therefore, based on gross evaluation, acoustic pressures of 0.98 MPa and higher were considered unsafe and unsuitable for further study. We therefore continued our safety assessment with detailed histology on samples that were sonicated with acoustic pressures of 0.75 MPa and lower.

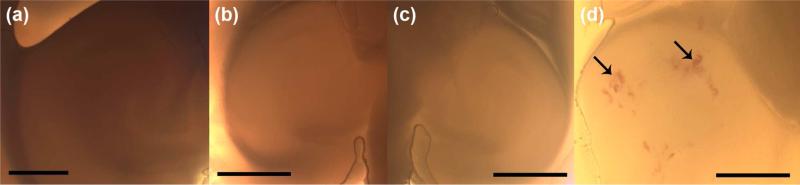

Figure 3.

Gross examination of three brain samples sonicated at the left hippocampal region at pressure amplitudes of (a) 0.61 MPa, (b) 0.75 MPa, and (d) 0.98 MPa. The right hippocampus of one brain is shown in (c) as the control un-sonicated region. Arrows in (d) indicate gross hemorrhage in various locations in the left hippocampus. Magnification and scale bars in (a-c) are 20x and 1 mm, and in (d) 40x and 500 μm, respectively.

2.2 Microscopic Evaluation

Table 2 shows the number of brains studied at various acoustic pressures and different post-opening periods in addition to the percentage experiencing BBB opening. H&E sections containing BBB-opened regions (as concluded by fluorescence imaging of adjacent unstained sections, Figs. 2a and 2e) were selected and analyzed for damage. As expected, all control, non-sonicated brains exhibited normal tissue histology at both hippocampi (Fig. 4a). For the majority of sonicated brains, the control right hippocampus was free of distinct damaged sites (Fig. 4c), i.e., only few damaged neurons and scattered RBC extravasations were observed.

Table 2.

Number of brain samples studied for microscopic evaluation at various acoustic pressures (0-0.75 MPa) and at different survival periods (30 min and 5 hr).

| Pressure amplitude (MPa) | Number of brains (30 min post-opening) | Number of brains (5 h post-opening) | Number of brains (Total) | Number of brains with BBB opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 (0%) |

| 0.30 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 (57%) |

| 0.46 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 7 (100%) |

| 0.61 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 6 (86%) |

| 0.75 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 7 (100%) |

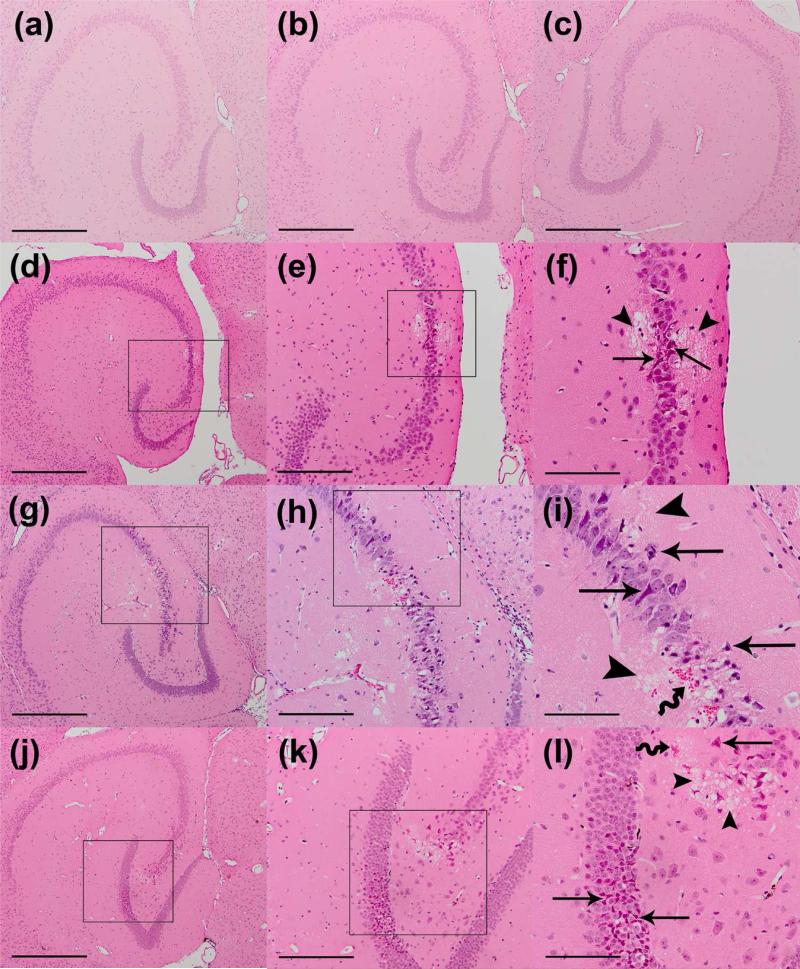

Figure 4.

Microscopic examination of left and right hippocampi in H&E-stained 6-μm thick horizontal sections of (a) un-sonicated control, (b-c) 0.30 MPa, (d-f) 0.45 MPa, (g-i) 0.61 MPa , and (j-l) 0.75 MPa brain samples. For these brains, mice were sacrificed five hours (0.30 and 0.61 MPa) or 30 minutes (0.45 and 0.75 MPa) after sonication. Normal tissue histology is shown in the left hippocampus of a control brain with no microbubble injection and no sonication (a). Sonicated brains at 0.30 MPa show no histological damage at the left hippocampus (b), similar to the un-sonicated right hippocampus of the same brain (c). Minor microscopic damage is noticeable in one location at the pyramidal neurons of the left hippocampus sonicated at 0.45 MPa, constituting one distinct damaged site (d-f). Brain samples sonicated with pressure amplitudes of 0.61 MPa (g-i) and 0.75 MPa (j-l) show higher incidence of microscopic damage at multiple distinct damaged sites around the pyramidal and granular neurons. Straight arrows point to damaged neurons and wiggly arrows point to RBC extravasations. Arrowheads show areas of microvacuolation at the damaged site. Black boxes inside the left and middle column show enlarged regions in the middle column and right column, respectively. Magnifications and scale bars in (a-d, g, j) are 40x and 500 μm, in (e, h, k) 100x and 200 μm, and in (f, I, l) 200x and 100 μm, respectively.

At 0.30 MPa, little or no tissue effects were noted in the sonicated samples (Fig. 4b). Few microvacuolations and extravasated erythrocytes were identified at the left hippocampus in 18% of the examined sections. At 0.46 MPa, a greater increase in number of extravasated red blood cells, dark neurons, and microvacuolations at the left hippocampal region was observed (Figs. 4d-f and 5). The damage was detected in 32% of the examined sections. At the acoustic pressures of 0.61 (Figs. 4g-i) and 0.75 MPa (Figs. 4j-l), the amount of tissue effects increased considerably and larger regions of microvacuolations, RBC extravasations, and neuronal damage were evident (Fig. 5). The incidence of tissue effects across the examined sections also increased to 66% and 77% in the 0.61 and 0.75 MPa samples, respectively (Fig. 5f).

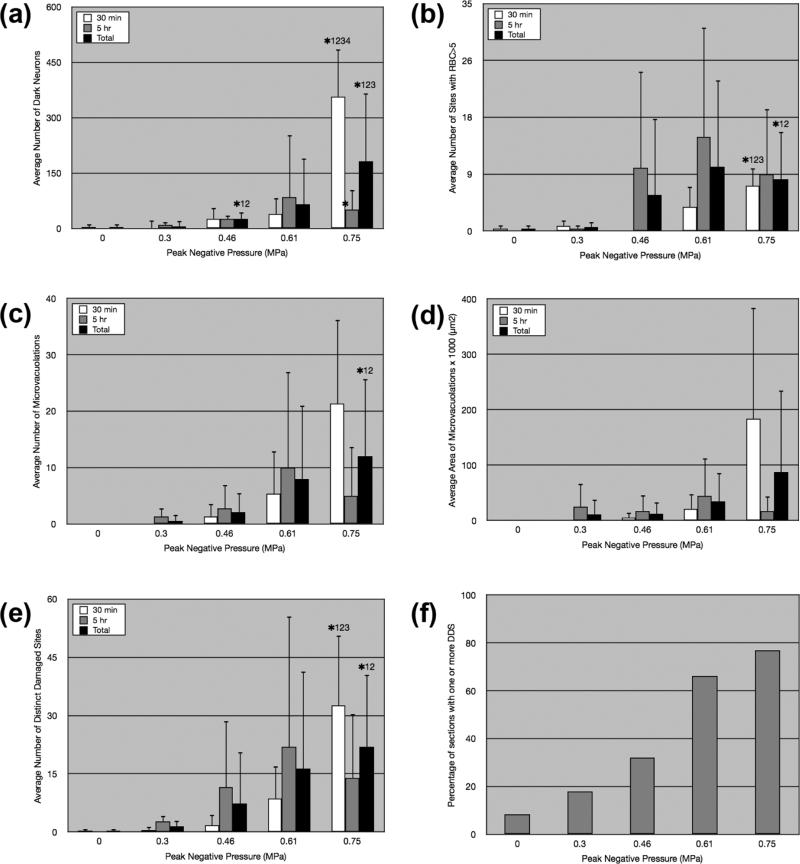

Figure 5.

Average number of dark neurons (a), average number of sites with extravasated RBCs of more than five (b), average number and area of microvacuolations (c-d), and average number of distinct damaged sites (e) in control (0 MPa) and sonicated brains (0.3-0.75 MPa) sacrificed 30 min (white bar) and 5 hr (gray bar) after sonication. The black bar indicates average values across different pressure amplitudes for total number of brains studied. The asterisks represent statistical significance (p<0.05) between the different acoustic pressures in the 30-min or total groups. The numbers next to the asterisk, i.e., 1, 2, 3, 4 correspond to 0, 0.3, 0.46, and 0.61 MPa, respectively. The asterisk between bars represents statistical significance (p<0.05) between the 30-min and 5-h samples. In (f), the percentage of sections that contained one or more distinct damaged sites (DDS) at the left hippocampal region is shown for each acoustic pressure. Total studied sections per sample were 24 in the control (0 MPa) and 56 in the sonicated brains (0.3-0.75 MPa).

The characteristics of lesions were similar in all samples but the size and number of lesions generally increased with higher pressure amplitudes. Within a lesion, microvacuolated areas lacking tissue structure consisted of large and tiny microvacuolations that gave the appearance of non-uniform pores in a focal region within the parenchyma (Figs. 4l and 6e). If they occurred close to the neuronal cell bodies in pyramidal and granular layers of hippocampus, they were always accompanied by neuronal damage and occasionally red blood cell extravasations (Figs. 4f and 4i). Dark neurons had darkly-stained basophilic nuclei with or without the appearance of shrunken, triangulated, and intensely stained acidophilic cell bodies (Figs. 4i and 4l).

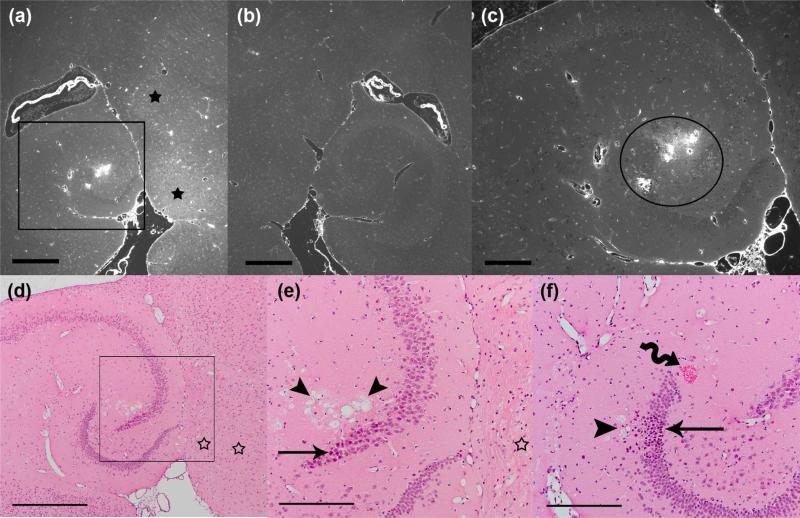

Figure 6.

Side-by-side comparison of BBB opening and histology with an unstained 6-micron paraffin section (a-c) and two adjacent H&E-stained sections (d-e and f). The animal was sonicated at a pressure amplitude of 0.75 MPa and sacrificed five hours later. The intensity of fluorescence as a result of dextrans leakage is significantly higher in the left hippocampus (a) compared to the right (b). Black stars in (a) indicate greater diffusion of dextrans into the brain parenchyma medial to the hippocampal fissure. The black boxes in (a and d) show the enlarged areas in (c and e), respectively. The H&E sections are 12 μm (d-e) and 80 μm (f) apart from the unstained section (a-c). Distinct damaged sites are apparent in the H&E-stained sections (d-e and f), at a location with intense BBB opening (depicted by the circle in c). The straight arrows point to damaged neurons and the wiggly arrow points to RBC extravasations. The arrowheads show areas of microvacuolation at the damaged site. Hollow stars in (d-e) show absence of major histological damage at locations where diffused BBB opening was observed (a). Magnifications and scale bars are 40x and 500 μm in (a-b and d), and 100x and 200 μm in (c and e-f), respectively.

As stated in the Materials and Methods section, we used three histological measures to quantify damage for similarly-treated brains sonicated in each pressure amplitude case: 1) average number of dark neurons, 2) average number of RBC extravasations, and 3) average number and area of microvacuolations. We also used average number of distinct damaged sites as a composite histological measure. These histological measures are average values of the net difference between the left and right hippocampi across similarly studied brains. The average number of distinct damaged sites in the 0.46-, 0.61-, and 0.75-MPa samples (total) increased by 5-, 11-, and 15-fold, respectively, compared to the 0.3 MPa samples (Fig. 5e, black bar). Similarly, there was a 5-, 13-, and 37-fold difference in the average number of dark neurons in 0.46, 0.61, and 0.75 MPa cases (total), respectively, compared to the 0.3 MPa case (Fig. 5a-b). While the incidence of tissue effects in all four categories increased with increasing pressure amplitude, the differences in average numbers were statistically significant (p<0.05) only between 0.75 MPa samples and 0-0.3 MPa (total: RBC extravasations, microvacuolations, DDS), 0.75 MPa samples and 0-0.46 MPa (total: dark neurons; 30 min: RBC extravasations, DDS), and 0.75 MPa samples and 0-0.61 MPa (30 min: dark neurons) (Figs. 5a-e). In the 5-h samples, there was no significant difference among the different pressure amplitudes for all histological measures. The difference in the average area of microvacuolation was also found to be insignificant among all pressure amplitudes and survival periods (Fig. 5d). In addition, no significant difference between the 30-min and 5-h specimens was observed at all pressure studies for all categories except for the dark neurons, where there was greater damage noted in the case of the 30-min, 0.75 MPa case (Fig. 5a).

3. Characterization of BBB Disruption and Histological Damage

In general, two types of fluorescence were observed in the sonicated regions of fluorescence images: 1) a diffuse and relatively uniform distribution of dextrans across the brain parenchyma, with higher levels at the thalamus (Figure 6a, black stars) and 2) a localized and highly-concentrated leakage of dextrans from larger microvessels (arterioles and venules) branching off of transverse hippocampal arteries and veins (Fig. 6c, black circle), or from other microvessels at the hippocampal fissure and thalamus. In most instances, the second type of fluorescence (detected in 0.46-0.75 MPa cases) was associated with the greatest damage to the vasculature and surrounding parenchyma. In other words, vascular effects detected in fluorescence images closely matched the nearby distinct damaged sites that included microvacuolations, necrotic neurons, and erythrocyte extravasations (Figure 6d-f). In contrast to the high-intense and patchy fluorescence that was mostly seen in pressure amplitudes of 0.46 MPa and higher, diffused fluorescence was observed in all pressures tested. Only a few of these regions had RBC extravasations (0.3-0.75 MPa), dark neurons, small microvacuolations, and less dense parenchyma (paler pink; 0.46-0.75 MPa). Mostly, however, little or no tissue effects were associated with diffuse BBB opening, especially at lower pressures (Figure 6d-e, hollow stars).

4. Qualitative Assessment of BBB Disruption and Histology in Region-Specific Areas of Brain

MR images of analyzed samples (0.3-0.75 MPa) have revealed contrast enhancement in the whole sonicated area, indicating diffuse BBB opening in both the hippocampus and thalamus (Figs. 2c, 2g, 2j). Similar results have been achieved with fluorescence imaging but with some differential fluorescent intensities in few specific regions. In the majority of fluorescent samples, BBB opening was more prominent close to the hippocampal fissure, thalamus, and around longitudinal and transverse hippocampal arteries.

In both imaging modalities, the amount of tracer diffusion varied substantially depending on the peak negative pressure used; higher pressures such as 0.61 and 0.75 MPa consistently resulted in larger areas of tracer diffusion and greater amounts of fluorescence (TR-tagged dextrans) and gadolinium. To a lesser extent, BBB disruption was distinguishable with a considerable amount of diffusion at 0.46 MPa, while samples sonicated at 0.30 MPa showed BBB opening but with a significant decrease in the amount and the extent of tracer diffusion.

In terms of safety assessment, neuronal damage was mainly detected in the pyramidal and granular layers of the hippocampus, while RBC extravasations were equally noticed around the vessels in both the thalamus and the hippocampus (Fig. 5). Microvacuolations, on the other hand, were mostly evident in the neuropil of the hippocampus, especially around the microvessels. In some cases, microvacuolations were accompanied by RBC extravasations and dark neurons at a localized area in the hippocampal region, and to a lesser extent in the thalamus. As described in a previous section, distinct damaged sites were mostly associated with patchy opening of the BBB in the left hippocampal region that lay within the focal region of the ultrasound beam.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the short-term safety profile (up to five hours post sonication) of the FUS-UCA-induced BBB opening under specific sonication parameters. Particularly, we sought to determine the acoustic pressures that induced BBB opening with no or minimal tissue effects. We performed a combination of fluorescence and bright-field imaging to detect and assess the extent of BBB opening and associated tissue effects in the sonicated locations of the left hippocampal region. We used fluorescent-tagged dextrans and gadolinium as tracers to confirm the opening, H&E staining for safety analysis, three histological measures to quantify the bioeffects, and a side-by-side qualitative analysis of adjacent sections to understand the underlying mechanism of induced opening and damage. Our results provide several important findings and insights that are summarized and discussed below.

Under the experimental conditions of our study, the BBB opening pressure threshold was found to be 0.15-0.3 MPa peak-negative pressure, based on the fact that 70% (7/10) of the brains (0.30 MPa) underwent opening as confirmed by both MRI and fluorescence imaging (Figure 2; Table 1). However, this percentage combined the results of both imaging modalities used to detect opening. The sizes of Omniscan™ (573.7 Da) and dextrans (3000 Da) are different in magnitude, so there may be a higher percent opening when only gadolinium is used. Indeed, lack of opening in three out of 10 samples was only observed in brains, where dextrans were injected after sonication. It is very likely that the threshold of BBB opening is in fact at 0.3 MPa with 100% probability for compounds smaller than 3 kDa. The absence of opening at 0.15 MPa as imaged via MRI (Figure 2i; Table 1) and confirmed by other studies (Choi et al. 2010b) and the presence of BBB opening in 77% (10/13) of 0.46 MPa samples also support this finding. However, we should note that the methodology used for MRI acquisition using intraperitoneally injected contrast agent presents a time delay from the time of sonication that may fail to detect an early low-level BBB disruption. Whether a 0.15-0.3 MPa threshold holds true for greater molecular weight compounds and different sonication parameters and different protocols remains to be confirmed.

Gross evaluation of thick brain slices sonicated with 0.46-0.98 MPa ranging pressures revealed large-scale detectable hemorrhage only in the 0.98 MPa case, hence eliminating pressure amplitudes of higher than 0.75 MPa from further study. Thorough microscopic examination of thin H&E-stained sections from 0.3-0.75 MPa sonicated brains showed minimal tissue effects in 0.3 and 0.46 MPa samples, while at 0.61 and 0.75 MPa acoustic pressures, multiple distinct damaged sites with higher frequency of occurrence were detected (66 and 76% of studied sections, respectively; Figure 5f). As described previously, DDS was defined to incorporate microvacuolations, necrotic neurons, and RBC extravasations in one single measure. This composite measure of histological damage provided higher accuracy, greater consistency, and less subjective analysis of safety across different brain samples. Two histologists may differ on the exact number of dark neurons or microvacuolations present, but they are likely to agree on the number of distinct damaged areas in the same section. In all analyzed samples (30-min and 5-h), the average number of distinct damaged sites increased by 5-, 11-, and 15-fold in the 0.46-, 0.61-, and 0.75-MPa samples, respectively, compared to 0.3-MPa samples (Fig. 5e, black bar). However, the differences in the average numbers were statistically significant (p<0.05) only between the 0.75-MPa and the 0-0.3 MPa cases. Similar significance was also observed in the average number of microvacuolations and RBC-extravasated sites.

Comparison of data from different survival periods indicated that increasing acoustic pressures from 0.3 to 0.75 MPa resulted in no significant increase in tissue effects when histology was assessed after five hours of survival. Moreover, the number of lesions did not increase or decrease significantly when 30-min samples were compared to the 5-h ones (one exception was the decrease in number of dark neurons at 0.75 MPa between the 30-min and 5-h samples; Fig. 5a). This suggests that the effects of the FUS-UCA interaction on the vasculature and surrounding tissue are immediate and not accumulative over time. Moreover, significant decrease in number of dark neurons at 0.75 MPa could indicate that neuronal injury is more severe at this pressure amplitude compared to lower pressures, possibly due to prolonged ischemia. It is likely that necrotic cells are cleared quickly within first few hours of sonication, lowering their detection level after five hours. It should be noted that even though histologically there was no significant difference in tissue effects between 30min and 5h samples, there is a possibility that the initial damage caused by higher-pressure amplitudes may bring about long-term behavioral, functional, or pathological changes that have not been observed or quantified yet. Further studies are needed for a better understanding of damage/repair mechanisms that come into effect following the sonication. Based on these results, we can only claim that pressure amplitudes of 0.3-0.46 MPa have shown the least amount of tissue effects (while successfully opening the BBB) at both tested time periods within the 5h window (30 min and 5h).

Our side-by-side analysis of BBB opening in the hippocampal region (as detected by fluorescence microscopy) and the histological damage in that area (as assessed by H&E staining) demonstrated a close association between the types of observed fluorescence and the types and extent of tissue effects. The majority of distinct damaged sites were detected near severely-affected microvessels that presented localized opening with patchy and intense fluorescence around them (0.46-0.75 MPa). In contrast, sonicated areas with diffusely opened BBB showed minimal tissue effects in H&E-stained sections, limited to few red blood cell extravasations, few scattered dark neurons, and less dense parenchyma in few small regions (0.3-0.75 MPa).

Inertial cavitation of microbubbles as a result of FUS exposure may contribute to the vascular effects that were described here, while non-inertial cavitation of microbubbles may cause the uniformly diffuse BBB opening. Several studies directly support this notion. In a recent vessel phantom study reported by our group (Tung et al., 2010), the inertial cavitation threshold of Definity microbubbles was determined to be 0.46 MPa. Preliminary results of in vivo studies by our group are also in agreement with this finding. The significance of 0.4-0.46 MPa as the inertial cavitation threshold of microbubbles becomes evident when histological findings are taken into account. At 0.3 MPa, the tissue effects were limited to few scattered RBC extravasations and very few small microvacuolated areas (18% of sections, Figs. 4b and 5f). Starting at 0.46 MPa, however, the presence of distinct damaged sites consisting of several types of damage in one local region (32% of sections, Figs. 4d-f) was noted. The fact that average numbers of DDS, microvacuolations, and RBC extravasations were significantly higher at 0.75 MPa with respect to 0.3 MPa, but not 0.46 MPa (Figs. 5b, 5c, and 5e), supports this assertion, i.e., that inertial cavitation and its related effects was triggered at 0.46 MPa and beyond. Recent in vivo cavitation studies performed by our group (Tung et al. 2009) further support this hypothesis (Tung et al. 2009). It is also noteworthy to mention that, despite the differences in some experimental parameters compared to our study (such as frequency), Hynynen et al. reported similar findings regarding the BBB opening threshold and damage (Hynynen et al., 2006; McDannold et al., 2007). In a study with Optison microbubbles (frequency: 0.26 MHz, burst length: 10 ms, PRF: 1 Hz), an acoustic pressure of 0.2 MPa was determined as the BBB opening threshold (McDannold et al., 2006; Hynynen et al., 2006). 80% BBB opening occurred at 0.3 MPa and tissue damage was apparent at 0.4 MPa and higher (Hynynen et al., 2006). Hence, these results and our current findings are consistent with the fact that BBB opening can occur without inertial cavitation as detected by wideband acoustic emission in vivo.

The type of microbubble activity that results from an interaction with the ultrasound beam is likely to be the major contributing factor to the underlying mechanism of BBB opening and associated damage. First, it is predicted that the inertial cavitation of microbubbles and their collapse in an ultrasound field may produce forceful fluid jets and shock waves against the vessel walls with direct and indirect mechanical stress on the tight junctions of the endothelial cells, thereby severely disrupting the anatomical barrier at that location (Hynynen et al., 2006; Leighton, 1994). This can cause extensive leakage of molecules from the blood, including RBCs and tracer molecules (hence, the intense fluorescence of dextrans). Distal to the severed vessels where there is reduced blood flow, ischemic regions may undergo acute necrosis and tissue deterioration (Charriaut-Marlangue et al., 1998; Chen et al., 1997; Kogure and Kogure, 1997; Li et al., 1998; Macdonald and Stoodley, 1998; Rosenblum, 1997). It is likely that the dark necrotic neurons and the microvacuolated neuropil presented here are the results of such ischemic episodes. Non-inertial cavitation of microbubbles, on the other hand, is thought to act on small arterioles and capillaries, where radiation forces and mechanical forces from bubble oscillations (Tung et al., 2010) and acoustic streaming (Hynynen 2008) may be translated to modified signal transduction at the endothelial cell surface, promoting transcellular transport of molecules or their paracellular passage by reducing the expression of tight junctional proteins. Understanding of this mechanism may help unveil the type of physiological disruption of the blood-brain barrier, with fewer damaging effects on the vasculature and the surrounding tissue.

Based on the findings reported in this paper, we believe that with the correct combination of sonication parameters we will be able to reduce the number of severely damaged vessels by operating under the inertial cavitation threshold. Preliminary studies by our group indicate that reducing the pulse repetition frequency may reduce patchy regions while promoting a more diffuse opening of the blood-brain barrier. A reduced number of pulses may allow the microbubbles to enter the hippocampus and the capillaries, resulting in fewer concentrated bubbles at the arteriolar level. It is still critical that lower peak negative pressures such as 0.3-0.46 MPa are used to decrease microbubble cavitation activity and minimize the tissue effects.

Finally, our safety assessment is limited in several respects. First, H&E staining is not sufficient to fully understand the scope of histological damage since axons, glial cells, and inflammatory molecules are difficult to detect and identify in H&E-stained sections. As a result, additional staining of the affected tissue is needed for H&E validation (such as TUNEL) as will be performed in future studies. Second, the eight sections that were analyzed (from twelve separate levels spanning the entire hippocampus) may underestimate the actual damage because of the skipped 80μm distance between each level, in addition to the rest of the brain outside the 12 levels that lie within the focal region of the ultrasound beam.

This study focused on short-term histological assessment of FUS-UCA-induced blood-brain barrier opening in mice. Our study is only a step toward understanding the safety of FUS-UCA and the short-term risks that it presents. Ongoing studies will address the safety of the procedure after longer survival times (up to 7 days). Moreover, assessment of the procedure's safety profile is incomplete without performing long-term behavioral and functional studies (EEG, evoked potentials) following the sonication. For better accuracy, physiological monitoring of factors that may contribute to brain injury from ischemia in a larger species will be undertaken in follow-up studies. Finally, the acoustic parameters need to be optimized for maximum diffuse BBB opening at the targeted region and minimal anatomical and physiological damage.

CONCLUSION

Under the specific parameters used in this study, we determined the threshold for blood-brain barrier opening to be between 0.15-0.3 MPa. Comparison of 30min and 5h data across all tested pressures showed no significant difference in tissue effects between the samples. For both survival time periods (30min and 5h), it was only the lower pressure amplitudes that showed least amount of short-term effects (0.3-0.46 MPa). Side-by-side analysis of blood-brain barrier opening, as detected by fluorescence imaging and MRI, and histology revealed two types of fluorescence intensity changes and associated tissue effects: 1) an intensely localized disruption with nearby vascular effects and distinct damaged sites, and 2) a mildly diffuse opening across the brain parenchyma with minimal tissue deterioration. Thus, we conclude that selecting the appropriate sonication parameters can eliminate, or significantly reduce, the severity of blood-brain barrier disruption in the affected microvessels, and result in a diffuse and safe opening of the blood-brain barrier in the capillaries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01EB009041-01 and R21EY018505), the National Science Foundation (CAREER 0644713) and the Kinetics Foundation. The authors wish to thank Shunichi Homma, M.D. (Department of Cardiology, Columbia University) for making the microbubbles (Definity®) available for this study. The help of Shougang Wang, Ph.D., Fotis Vlachos, Ph.D., and Eugenia Kwon (Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University) in assisting with some of the in vivo mouse experiments is much appreciated. The authors also thank the guidance of Maria Falangola, M.D., Ph.D. (Department of Radiology, New York University) in the assessment of histology and tissue damage.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakay L, Ballantine HT, Jr., Hueter TF, Sosa D. Ultrasonically produced changes in the blood-brain barrier. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1956;76:457–67. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1956.02330290001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine HT, Jr., Hueter TF, Nauta WJ, Sosa DM. Focal destruction of nervous tissue by focused ultrasound: biophysical factors influencing its application. J Exp Med. 1956;104:337–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.104.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo RH, Laske DW, Akbasak A, Morrison PF, Dedrick RL, Oldfield EH. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2076–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammermeyer J. The post-mortem origin and mechanism of neuronal hyperchromatosis and nuclear pyknosis. Exp Neurol. 1960;2:379–405. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(60)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammermeyer J. Is the solitary dark neuron a manifestation of postmortem trauma to the brain inadequately fixed by perfusion? Histochemistry. 1978;56:97–115. doi: 10.1007/BF00508437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charriaut-Marlangue C, Remolleau S, Aggoun-Zouaoui D, Ben-Ari Y. Apoptosis and programmed cell death: a role in cerebral ischemia. Biomed Pharmacother. 1998;52:264–9. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(98)80012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jin K, Chen M, Pei W, Kawaguchi K, Greenberg DA, Simon RP. Early detection of DNA strand breaks in the brain after transient focal ischemia: implications for the role of DNA damage in apoptosis and neuronal cell death. J Neurochem. 1997;69:232–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Pernot M, Brown TR, Small SA, Konofagou EE. Spatio-temporal analysis of molecular delivery through the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound. Phys Med Biol. 2007a;52:5509–30. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/18/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Pernot M, Small SA, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive, transcranial and localized opening of the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound in mice. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007b;33:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Wang S, Brown TR, Small SA, Duff KE, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive and transient blood-brain barrier opening in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's double transgenic mice using focused ultrasound. Ultrason Imaging. 2008;30:189–200. doi: 10.1177/016173460803000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Wang S, Tung YS, Morrison III B, Konofagou EE. Molecules of various pharmacologically-relevant sizes can cross the ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in vivo. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010a;36:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Feshitan JA, Baseri B, Wang S, Borden MA, Konofagou EE. Microbubble-size dependence of focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in mice in vivo. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010b;57:145–54. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2034533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Gottschlich R, Seelig A. Blood-brain barrier permeation: molecular parameters governing passive diffusion. J Membr Biol. 1998;165:201–11. doi: 10.1007/s002329900434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesecke T, Hynynen K. Ultrasound-mediated cavitation thresholds of liquid perfluorocarbon droplets in vitro. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1359–65. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00980-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habgood MD, Begley DJ, Abbott NJ. Determinants of passive drug entry into the central nervous system. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20:231–53. doi: 10.1023/A:1007001923498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K. Ultrasound for drug and gene delivery to the brain. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, McDannold N, Sheikov NA, Jolesz FA, Vykhodtseva N. Local and reversible blood-brain barrier disruption by noninvasive focused ultrasound at frequencies suitable for trans-skull sonications. Neuroimage. 2005;24:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology. 2001;220:640–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2202001804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Raymond S, Weissleder R, Jolesz FA, Sheikov N. Focal disruption of the blood-brain barrier due to 260-kHz ultrasound bursts: a method for molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:445–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jortner BS. Neuropathological assessment in acute neurotoxic states. The “dark” neuron. J Med CBR Def. 2005:3. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, McDannold N, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Noninvasive localized delivery of Herceptin to the mouse brain by MRI-guided focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006a;103:11719–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604318103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, McDannold N, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Targeted delivery of antibodies through the blood-brain barrier by MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006b;340:1085–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure T, Kogure K. Molecular and biochemical events within the brain subjected to cerebral ischemia (targets for therapeutical intervention). Clin Neurosci. 1997;4:179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll RA, Neuwelt EA. Outwitting the blood-brain barrier for therapeutic purposes: osmotic opening and other means. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1083–99. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199805000-00082. discussion 1099-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton TG. The Acoustic Bubble. Academic; San Diego, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Powers C, Jiang N, Chopp M. Intact, injured, necrotic and apoptotic cells after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Neurol Sci. 1998;156:119–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossinsky AS, Vorbrodt AW, Wisniewski HM. Scanning and transmission electron microscopic studies of microvascular pathology in the osmotically impaired blood-brain barrier. J Neurocytol. 1995;24:795–806. doi: 10.1007/BF01191215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Stoodley M. Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:1–11. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Targeted disruption of the blood-brain barrier with focused ultrasound: association with cavitation activity. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:793–807. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/4/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Use of ultrasound pulses combined with Definity for targeted blood-brain barrier disruption: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:584–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Effects of acoustic parameters and ultrasound contrast agent dose on focused-ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:930–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Raymond S, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. MRI-guided targeted blood-brain barrier disruption with focused ultrasound: histological findings in rabbits. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesiwala AH, Farrell L, Wenzel HJ, Silbergeld DL, Crum LA, Winn HR, Mourad PD. High-intensity focused ultrasound selectively disrupts the blood-brain barrier in vivo. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:389–400. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. Drug and gene delivery to the brain: the vascular route. Neuron. 2002;36:555–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. Modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. J Drug Target. 1996;3:417–25. doi: 10.3109/10611869609015962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond SB, Treat LH, Dewey JD, McDannold NJ, Hynynen K, Bacskai BJ. Ultrasound enhanced delivery of molecular imaging and therapeutic agents in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum WI. Histopathologic clues to the pathways of neuronal death following ischemia/hypoxia. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14:313–26. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikov N, McDannold N, Sharma S, Hynynen K. Effect of focused ultrasound applied with an ultrasound contrast agent on the tight junctional integrity of the brain microvascular endothelium. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1093–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikov N, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Cellular mechanisms of the blood-brain barrier opening induced by ultrasound in presence of microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:979–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treat LH, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang Y, Tam K, Hynynen K. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin to the rat brain at therapeutic levels using MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:901–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung YS, Choi JJ, Baseri B, Konofagou EE. Identifying the Inertial Cavitation Threshold and Skull Effects in a Vessel Phantom Using Focused Ultrasound and Microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:840–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung YS, Choi JJ, Konofagou EE. Identifying the Inertial Cavitation Threshold of Monodispersed Microbubbles and Skull Effects Using FUS. International Society on Therapeutic Ultrasound (ISTU) Proceedings. 2009;1215:186–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Choi JJ, Tung YS, Morrison III B, Konofagou EE. IEEE Proc Symp Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. Beijing, China: 2008. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the molecular delivery through the ultrasound-enhanced blood-brain barrier opening in the murine brain. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver M, Laske DW. Transferrin receptor ligand-targeted toxin conjugate (Tf-CRM107) for therapy of malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2003;65:3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1026246500788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Boska MD, Lof J, Uberti MG, Tsutsui JM, Porter TR. Effects of transcranial ultrasound and intravenous microbubbles on blood brain barrier permeability in a large animal model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:2028–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang FY, Fu WM, Yang RS, Liou HC, Kang KH, Lin WL. Quantitative evaluation of focused ultrasound with a contrast agent on blood-brain barrier disruption. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]