Abstract

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is being actively evaluated as an emerging complementary or alternative procedure for evaluation of the colon. The yield of CCE is significantly dependent on the quality of bowel preparation. In addition to achieving a stool-free colon the bowel preparation protocols need to decrease bubble effect and aid propulsion of the capsule.

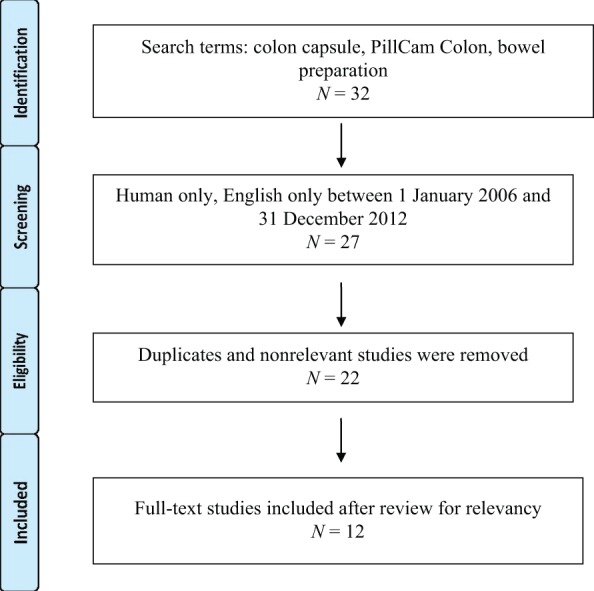

An extensive English literature search was done using PubMed with search terms of colon capsule endoscopy, PillCam and bowel preparation. Full-length articles which met the criteria were included for review.

A total of 12 studies including 1149 patients were reviewed. There was significant variability in the type of bowel preparation regimens. Large-volume (3–4 liters) polyethylene glycol (PEG) was the most widely used laxative. Lower volumes of PEG showed comparable results but larger studies are needed to determine efficacy. Sodium phosphate was used as an effective booster in most studies. Magnesium citrate and ascorbic acid are emerging as promising boosters to replace sodium phosphate when it is contraindicated. The potential benefit of prokinetics needs further evaluation.

Over the past decade there has been significant improvement in the bowel preparation regimens for CCE. Further experience and studies are likely to standardize the bowel preparation regimens before CCE is adopted into routine clinical practice.

Keywords: bowel preparation, capsule colonoscopy, regimens, review

Introduction

Capsule endoscopy has now been in use for many years to visualize and diagnose abnormalities of the small bowel [Iddan et al. 2000; Fireman and Kopelman, 2007; Van Gossum et al. 2009]. In recent years colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) has been under evaluation for visualization of the colon [Eliakim et al. 2006, 2009; Schoofs et al. 2006; Sieg et al. 2009; Gay et al. 2010; Spada et al. 2010; Herrerias-Gutierrez et al. 2011; Sieg, 2011]. The advantages of CCE as an alternative to the standard colonoscopy as a screening test for colorectal cancer (CRC) might be attractive for a subset of patients. CCE is a minimally invasive, painless procedure without the need for sedation or the discomfort of air insufflations [Fireman and Kopelman, 2007]. These features can allure patients who are afraid of the risks involved with colonoscopy and improve the implementation of our CRC screening program. As with routine colonoscopy, CCE does need bowel preparation to clean the colon. With increasing experience with CCE different bowel preparation regimens have been used with variable results. This article summarizes the studies describing bowel preparation regimens for CCE to assist gastroenterologists in preparing for an optimal capsule colon exam.

Materials and methods

An extensive English language literature search was done using PubMed for full articles, abstracts and review articles up to 31 December 2012. The following key words were used: colon capsule endoscopy, bowel preparation and PillCam Colon. The references of pertinent studies and review articles were manually searched. A total of 32 relevant articles were identified. Twenty articles were eligible for review, which included 14 studies, 2 meta-analysis and 4 review articles (Figure 1). A meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the study designs and bowel preparations used. We systematically analyzed and abstracted each study for the following characteristics:

Figure 1.

Literature review search schematic.

(1) year of publication,

(2) county were study was conducted,

(3) number of patients included in the study,

(4) single or multicentered,

(5) device used,

(6) type of bowel preparation used,

(7) diet modifications,

(8) prokinetic use,

(9) level of colon cleanliness,

(10) mean transit time of colon capsule,

(11) CCE excretion rate,

(12) sensitivity and specificity of polyp detection.

Results

Full articles were available for 12 studies and were included (Figure 1). Six of the studies were multicentered and were conducted in Israel [Eliakim et al. 2006], Japan [Kakugawa et al. 2012], Italy [Spada et al. 2011c] and three across multiple countries in Europe [Eliakim et al. 2006, 2009; Spada et al. 2011b]. The single-center studies were conducted in Spain [Eliakim et al. 2009], Belgium [Schoofs et al. 2006], Germany [Sieg et al. 2009; Hartmann et al. 2012], France [Gay et al. 2010] and Italy [Spada et al. 2011a]. Most of the studies were conducted with PillCam Colon 1 (PCC1). Only two studies used PCC2 [Eliakim et al. 2009; Spada et al. 2011b]. Only four studies had a sample size of more than 100 [Van Gossum et al. 2009; Gay et al. 2010; Spada et al. 2010, 2011b].

Devices

Given Imaging Ltd (Yoqneam, Israel) offers CCE under the name of PillCam Colon. PCC1 measures 11 mm × 31 mm with two imagers, one at each end of the capsule with a frame rate of 4 frames/s. It has a battery life of 10 h [Sieg, 2011]. The new second-generation PCC2 is similar to PCC1 with many new features. PCC2 has a wider angle of view (172° versus 156° for the first-generation colon capsule), allowing almost 360° coverage [Adler and Metzger, 2011; Sieg, 2011]. A new data recorder (DR3) in PCC2 has an adaptive frame rate of 4–35 frames/s, the ability to generate customized alerts at different points to guide the patient or physician, and real-time visualization capacity. The new RAPID software has a tool integrated to estimate the polyp size. To make the examination interpretations easier, the new RAPID 6 software has flexible spectral intelligent color enhancement to improve image quality and pathology visualization [Eliakim, 2010].

Colon cleanliness

Optimal bowel preparation is important for a good colonoscopic exam and hence the desired yield of colonoscopy. Studies have reported sensitivity to detect polyps greater than 6 mm ranging from 84% to 89% with the use of PCC2 [Fireman and Kopelman, 2007; Spada et al. 2011c]. However, the quality of bowel preparation and the capsule interpretation appear to be the two most significant factors affecting the yield of capsule endoscopy [Sieg, 2011]. The obvious technical inability to wash the colon or aspirate the contents of the colon during capsule endoscopy in contrast to standard colonoscopy requires superior bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy to be effective. The sensitivity of detecting polyps greater than 6 mm was shown to increase from 42% for fair to poor cleanliness to 75% with good to excellent bowel cleanliness [Van Gossum et al. 2009]. Spada and colleagues showed significant improvement accuracy parameters with good bowel preparation [Spada et al. 2011c]. Sensitivity and specificity to detect polyps greater than 6 mm increased to 100% and 93% respectively with good to excellent cleansing level from 54% and 78% with poor to fair cleansing level.

It was shown that for the capsule endoscopy to be more cost effective than standard colonoscopy, the compliance for screening should be greater than 30% [Hassan et al. 2008]. The complexity and length of bowel preparation is a possible hindrance to completing and adhering to the preparation regimen.

Bowel preparation

Colon preparation for CCE has been specifically designed not only to clean the colon, but also to promote capsule propulsion and to create a watery medium for the capsule to move (Tables 1 and 2). Most of the bowel preparation regimens require lavage solutions, prokinetics and boosters. The most extensively used bowel preparations in the studies were PEG, sodium phosphate (NaP), bisacodyl and senna (Table 3).

Table 1.

Grading of bowel preparation.

| Description of findings | Status | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| No more than small bits of adherent feces | Excellent | 1 |

| Small amount of feces or dark fluid, but not enough to interfere with the examination | Good | 2 |

| Enough feces or dark fluid present to preclude a completely reliable examination | Fair | 3 |

| Large amount of fecal residue | Poor | 4 |

Table 2.

Bubble effect scale.

| Rating | Description |

|---|---|

| Significant | Bubbles that interfere with examination |

| More than 10% of surface area obscured by bubbles | |

| Insignificant | No bubbles or bubbles that do not interfere with examinationLess than 10% of surface area obscured by bubbles |

Table 3.

Summary of studies describing bowel preparation for capsule colonoscopy.

| Study [year] | Type of device | Bowel preparation regimen | Colon cleanliness | Sensitivity and specificity to detect polyps >6 mm |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||

| Eliakim et al. [2006] | PCC1 | Day 2 | Low-fiber diet | 84.4 | 63 | 94 |

| Day 1 | 7–8 p.m.: PEG 3 liters | |||||

| Day 0 | 6–7 a.m.: PEG 1 liter | |||||

| 8–9 a.m.: tegaserod 6 mg, capsule ingestion | ||||||

| [10 a.m.: NaP 30 ml+12 a.m.–1 p.m.: tegaserod 6 mg] | ||||||

| 2 p.m.: NaP 15 ml | ||||||

| 4:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Schoofs et al. [2006] | PCC1 | Day 2 | – | 88 | 76 | 64 |

| Day 1 | 6–9 p.m.: PEG 3 liters | |||||

| Day 0 | 6–7 a.m.: PEG 1 liter | |||||

| 8–9 a.m.: domperidone 20 mg, capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 10 a.m.: NaP 45 ml | ||||||

| 2 p.m.: NaP 30 ml | ||||||

| 4:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Sieg et al. [2009] | PCC1 | Day 2 | – | 72 | ||

| Day 1 | 1–6 p.m.: PEG 3 liters | |||||

| Day 0 | 6–7 a.m.: PEG 0.5 liter | |||||

| 8–9 a.m.: domperidone 20 mg, capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 10 a.m. NaP 22 ml | ||||||

| 12 a.m.–1 p.m.: NaP 22 ml | ||||||

| 4:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Van Gossum et al. [2009] | PCC1 | Day 2 | – | 72 | 64 | 84 |

| Day 1 | 6–9 p.m.: PEG 3 liters | |||||

| All day: clear liquid | ||||||

| Day 0 | 6–7 a.m.: PEG 1 liter | |||||

| 8–9 am: domperidone 20 mg, capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 10 a.m.: NaP 45 ml | ||||||

| 2 p.m.: NaP 22 ml | ||||||

| Eliakim et al. [2009] | PCC2 | Day 2 | – | 78 | 89 | 76 |

| Day 1 | Evening: PEG 2 liters | |||||

| Day 0 | Morning: PEG 2 liters | |||||

| 8–9 a.m.: capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 1–2 h later: NaP 45 ml | ||||||

| 2 h later: NaP 22 ml | ||||||

| 4:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Spada et al. [2011c] | PCC1 | Day 2 | – | 35/53 | 63 | 87 |

| Day 1 | Evening: PEG 3 liters | |||||

| Day 0 | Morning: PEG 1 liter | |||||

| 8–9 a.m.: domperidone 20 mg, capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 10 a.m.: NaP 45 ml/0.5 liter PEG | ||||||

| 2 p.m.: NaP 22 ml/ 0.5 liter PEG | ||||||

| 4:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Herrerias-Gutierrez et al. [2012] | PCC1 | Day 2 | Low-fiber diet | 65.5% | 84% | 62.5% |

| Day 1 | Clear liquids only | |||||

| 6–9 p.m.: PEG 3 liters | ||||||

| Day 0 | 7–8 a.m.: PEG 1 liter | |||||

| 8:45 a.m.: domperidone 20 mg | ||||||

| 9 a.m.: capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 11 a.m.: NaP 30 ml | ||||||

| 3 p.m.: NaP 15 ml | ||||||

| 5:30 p.m.: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| 8 p.m.: conventional colonoscopy | ||||||

| Spada et al. [2011] | PCC2 | Day 2 | Bedtime: senna: 4 tablets | 81 | 84 | 64 |

| Multicentered | Day 1 | All day: clear liquid diet | ||||

| 109 | Day 0 | Evening: PEG 2 liters | ||||

| Morning: PEG 2 liters | ||||||

| 10 a.m.: capsule ingestion | ||||||

| [domperidone 20 mg if capsule delayed in stomach > 1 h] | ||||||

| Small bowel detection: NaP 30 ml | ||||||

| 3h later: NaP 25 ml | ||||||

| 2 h later: bisacodyl supp. 10 mg | ||||||

| Kakugawa et al. [2012]* (reduced volume/conventional preparation) | PCC1 | Day 2 | – | 94/86 | – | – |

| Day 1 | Low-fiber diet | |||||

| Bedtime: sennoside 24 mg | ||||||

| Day 0 | Morning: mosapride 15 mg, PEG 2 liters with dimethicone 400 mg | |||||

| [additional PEG 300 ml if needed (max 600 ml)], capsule ingestion | ||||||

| 2h later: magnesium citrate 50 g/water 900 ml | ||||||

| 4h later: magnesium citrate 50 g/water 900 ml | ||||||

| 1h later: mosapride 5 mg | ||||||

Reduced volume preparation has been described. Conventional preparation consists of PEG 2 liters on day 1 in addition to reduced volume preparation.

NaP, sodium phosphate; PCC, PillCam Colon; PEG, polyethylene glycol; supp., suppository.

Diet

Low-residue diet

The role of a low-fiber diet in bowel preparation is questionable. Adding a low-fiber diet aims to reduce the amount of solid stool in the colon but dietary restrictions for many days can hinder the bowel preparation. In a study by Eliakim and colleagues patients were started on a low-fiber diet and adequate colon cleanliness was achieved in 88% [Eliakim et al. 2006]. But a few other studies failed to improve colon cleanliness using a low-fiber diet [Herrerias-Gutierrez et al. 2011; Spada et al. 2011a], while other studies achieved comparable colon cleanliness without a low-fiber diet [Iddan et al. 2000; Gay et al. 2010]. However, most studies have included a clear liquid diet a day before the procedure.

Laxatives

Polyethylene glycol

PEG has been used primarily as a laxative in bowel preparation using CCE. A large-volume (3–4 liters of PEG) lavage has been used in the majority of the studies [Eliakim et al. 2006, 2009; Schoofs et al. 2006; Sieg et al. 2009; Van Gossum et al. 2009; Gay et al. 2010; Herrerias-Gutierrez et al. 2011; Sieg, 2011; Spada et al. 2011a, 2011b, 2011c]. The use of 4 liters of PEG before CCE has also been recommended by the European Society of Gastroenterointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline (evidence level 4, recommendation grade D) [Hassan et al. 2008]. The dose of PEG can be split to increase tolerability and compliance. Many combinations of splitting have been used in the studies, however two common regimens of splitting the PEG have been reported: 3 liters + 1 liter (i.e. 3 liters of PEG on day 1 and 1 liter on day 0) [Schoofs et al. 2006; Van Gossum et al. 2009; Spada et al. 2011a, 2011c] and 2 liters + 2 liters [Gay et al. 2010; Spada et al. 2011b]. The level of cleanliness achieved with both of these combinations is similar but there are no comparative studies.

The large amount of laxative to be consumed before the procedure can be inconvenient and can deter patients. Few studies have attempted to reduce the volume of the bowel preparations. Kakugawa and colleagues reduced the dose of PEG to 2 liters by eliminating the use of PEG the day before the procedure and adding magnesium citrate as a booster [Kakugawa et al. 2012]. The colon cleanliness achieved by this preparation was very good (94%). In another study by Hartmann and colleagues, PEG and ascorbic acid were used to reduce the volume of bowel cleanser [Hartmann et al. 2012]. Overall, adequate bowel cleanliness was achieved in over 80% of patients (83% for the original preparation and 82% for the modified preparation). However, cecal and right-sided colon cleanliness was only 52% and 61% respectively. The study had a small patient population and this value did not achieve statistical significance. Further larger studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of low-volume bowel cleansers.

PEG is an electrolyte lavage solution that has been in use as a standard bowel cleanser for decades. It is an isosmotic solution and causes less fluid exchange across the colonic membrane [Keeffe, 1996]. Biochemical changes like hypokalemia, hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia are less likely to occur with PEG compared with low-volume hyperosmolar preparations [Tan and Tiandra, 2006]. PEG is especially preferred in patients with electrolyte or fluid imbalances, such as renal or liver insufficiency, congestive heart failure or liver failure. PEG does not alter the histological features of colonic mucosa and may be used in patients suspected of having inflammatory bowel disease without obscuring the diagnostic capabilities. However, PEG was noted to produce more nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, sleep disturbance, perianal pain and irritation compared with hyperosmotic preparations [Tan and Tiandra, 2006].

Boosters

Capsule propulsion through the small intestine and colon to complete visualization of the colon before the end of the battery life is another important goal of the preparation. To help achieve this, boosters are added to the bowel preparation using capsule endoscopy.

Sodium phosphate (NaP)

NaP has been used as an effective booster propelling the capsule and achieving high excretion rates [Eliakim et al. 2006, 2009; Schoofs et al. 2006; Sieg et al. 2009; Van Gossum et al. 2009; Spada et al. 2011a, 2011b]. In a study by Sieg and colleagues the colon transit time was increased to a median of 8.25 h from 4.5 h when NaP was excluded [Sieg et al. 2009].

NaP agents cleanse the colon by osmotically drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen. This volume effect can allow the capsule to move in a watery medium, aiding in capsule propulsion. NaP-based bowel-cleansing agents are available in two forms: aqueous solution and tablet. Aqueous NaP (such as Fleet Phospho-soda, Fleet, Lynchburg, Virginia, USA) is a low-volume hyperosmotic solution containing 48 g of monobasic NaP and 18 g of dibasic NaP per 100 ml.

The booster is administered in two timed intervals. The first booster is administered when the capsule first hits the small bowel. The second booster dose is given 3–4 h following the first dose. Different doses have been used in the studies: 45 ml, 30 ml and 22 ml doses have been used as the first booster. The second dose of booster is usually smaller than the first dose.

As NaP acts by drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen, significant volume and electrolyte shifts may occur. In older patients with renal insufficiency, cardiovascular diseases and small intestinal diseases, poor gut motility and serious electrolyte imbalances have been reported [Lieberman et al. 1996; Gutierrez-Santiago et al. 2006]. Hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, hypokalemia and hypernatremia have been associated with NaP [Lieberman et al. 1996; Gutierrez-Santiago et al. 2006].

Due to concerns about the adverse effects of NaP, Spada and colleagues compared a standard regimen (PEG + NaP) and a modified regimen in which NaP boosters were substituted with one or two PEG boosters [Spada et al. 2011c]. But the study showed that the use of NaP boosters achieved 100% excretion rate in less than 10 h compared with 75% when it was excluded. The mean colonic transit time was also increased twofold when NaP boosters were not used.

Magnesium citrate

In a pilot study by Kakugawa and colleagues magnesium citrate was used as a booster in an attempt to reduce the total volume of bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy [Kakugawa et al. 2012]. In this study PEG was administered on the day of the procedure and the capsule was ingested after bowel preparation quality was assessed by experienced medical staff. This was followed by administration of isotonic magnesium citrate boosters. A total of 94% of patients who had reduced volume preparation had adequate bowel cleanliness compared with 86% who had conventional preparation. Reduced volume preparation also decreased the mean fluid intake to 3.8 liters compared with the total fluid intake of 4.5–6 liters using the conventional volume method [Eliakim et al. 2006; Schoofs et al. 2006; Sieg et al. 2009; Van Gossum et al. 2009]. The authors attributed the lower capsule excretion rate of 71% using this method to the lack of use of a bisacodyl suppository. It was also suggested that a third booster would increase the excretion rate.

Isotonic magnesium citrate reduces electrolyte imbalances and can be used as a booster in patients with renal impairment. It can play an important role when NaP cannot be used due to its potential to cause acute renal nephropathy. Further larger studies need to be conducted to evaluate the efficacy of magnesium citrate.

Bisacodyl

Bisacodyl works as a stimulant laxative. In CCE, bisacodyl is administered 2 h after the second NaP booster for the expulsion of the capsule and has been uniformly used across most studies. The swallowed capsule should ideally be excreted within 8–10 h with the help of bisacodyl.

Polyethylene glycol

In a pilot study Hartman and colleagues described the use of an additional 0.5 liter of PEG and an optional 0.25 liter of PEG as a booster during the capsule procedure with good results [Hartmann et al. 2012]. After an interim analysis, the morning dose of PEG was increased and 0.25 liter of PEG was added as a booster at an earlier time.

Prokinetics

Prokinetics are mainly used to help the progression of the capsule in the upper gut. Tegaserod, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 (5HT4) agonist, was used in an earlier study [Eliakim et al. 2006]. This drug is not available in the USA as it was withdrawn in 2007 by the US Food and Drug Administration due to the possible risk of cardiovascular disease. Domperidone, an antidopaminergic drug, has been more widely used in studies without any clear benefit [Eliakim et al. 2006; Schoofs et al. 2006; Sieg et al. 2009; Van Gossum et al. 2009; Herrerias-Gutierrez et al. 2011; Spada et al. 2011b, 2011c]. More recently mosapride, also a 5HT4 agonist which accelerates gastric emptying, has been used by Kakugawa and colleagues [Kakugawa et al. 2012]. The utility of adding a prokinetic is questionable. There are no studies comparing the efficacy of these drugs.

Summary

CCE is an evolving technique with the potential to be a noninvasive alternative for CRC screening. The role of a low-residue diet in the days leading up to CCE is questionable. PEG has been used as a laxative in most studies and is also recommended by ESGE. Split -dose PEG can potentially improve tolerability but there is not enough evidence to show improved bowel preparation. NaP, magnesium citrate and bisacodyl have been reported to improve colonic motility and decrease transit times with variable success. Prokinetics have failed to show any additional benefit. Further studies to optimize the bowel preparation regimen are likely to help in standardization and expand the use of CCE.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Shashideep Singhal, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 5141 Broadway, New York, NY 10034, USA.

Sofia Nigar, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, New York, NY, USA.

Vani Paleti, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, New York, NY, USA.

Devin Lane, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, New York, NY, USA.

Sushil Duddempudi, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, New York, NY, USA.

References

- Adler S., Metzger Y. (2011) PillCam Colon capsule endoscopy: recent advances and new insights. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 4: 265–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliakim R. (2010) Video capsule colonoscopy: where will we be in 2015? Gastroenterology 139: 1468–1471, 1471.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliakim R., Fireman Z., Gralnek I., Yassin K., Waterman M., Kopelman Y., et al. (2006) Evaluation of the PillCam Colon capsule in the detection of colonic pathology: results of the first multicenter, prospective, comparative study. Endoscopy 38: 963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliakim R., Yassin K., Niv Y., Metzger Y., Lachter J., Gal E., et al. (2009) Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy 41: 1026–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fireman Z., Kopelman Y. (2007) The colon – the latest terrain for capsule endoscopy. Dig Liver Dis 39: 895–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay G., Delvaux M., Frederic M., Fassler I. (2010) Could the colonic capsule PillCam Colon be clinically useful for selecting patients who deserve a complete colonoscopy? Results of clinical comparison with colonoscopy in the perspective of colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol 105: 1076–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Santiago M., Garcia-Unzueta M., Amado J., Gonzalez-Macias J., Riancho J. (2006) Electrolyte disorders following colonic cleansing for imaging studies. Medicina Clinica 126: 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D., Keuchel M., Philipper M., Gralnek I., Jakobs R., Hagenmuller F., et al. (2012) A pilot study evaluating a new low-volume colon cleansing procedure for capsule colonoscopy. Endoscopy 44: 482–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan C., Zullo A., Winn S., Morini S. (2008) Cost-effectiveness of capsule endoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 40: 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrerias-Gutierrez J., Arguelles-Arias F., Caunedo-Alvarez A., San-Juan-Acosta M., Romero-Vazquez J., Garcia-Montes J., et al. (2011) PillCam Colon capsule for the study of colonic pathology in clinical practice. study of agreement with colonoscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 103: 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iddan G., Meron G., Glukhovsky A., Swain P. (2000) Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature 405: 417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakugawa Y., Saito Y., Saito S., Watanabe K., Ohmiya N., Murano M., et al. (2012) New reduced volume preparation regimen in colon capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 18: 2092–2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeffe E. (1996) Colonoscopy preps: what’s best? Gastrointest Endosc 43: 524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D., Ghormley J., Flora K. (1996) Effect of oral sodium phosphate colon preparation on serum electrolytes in patients with normal serum creatinine. Gastrointest Endosc 43: 467–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoofs N., Deviere J., Van Gossum A. (2006) Pill Cam Colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy for colorectal tumor diagnosis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy 38: 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieg A. (2011) Colon capsule endoscopy compared with conventional colonoscopy for the detection of colorectal neoplasms. Expert Rev Med Devices 8: 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieg A., Friedrich K., Sieg U. (2009) Is Pill Cam Colon capsule endoscopy ready for colorectal cancer screening? A prospective feasibility study in a community gastroenterology practice. Am J Gastroenterol 104: 848–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada C., Hassan C., Ingrosso M., Repici A., Riccioni M., Pennazio M., et al. (2011a) A new regimen of bowel preparation for PillCam Colon capsule endoscopy: a pilot study. Dig Liver Dis 43: 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada C., Hassan C., Marmo R., Petruzziello L., Riccioni M., Zullo A., et al. (2010) Meta-analysis shows colon capsule endoscopy is effective in detecting colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8: 516–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada C., Hassan C., Munoz-Navas M., Neuhaus H., Deviere J., Fockens P., et al. (2011b) Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 74: 581–589.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada C., Riccioni M., Hassan C., Petruzziello L., Cesaro P., Costamagna G. (2011c) PillCam Colon capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial comparing two regimens of preparation. J Clin Gastroenterol 45: 119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Tiandra J. (2006) Which is the optimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy – a meta-analysis. Colorectal Disease 8: 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gossum A., Munoz-Navas M., Fernandez-Urien I., Carretero C., Gay G., Delvaux M., et al. (2009) Capsule endoscopy versus colonoscopy for the detection of polyps and cancer. N Engl J Med 361: 264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]