Abstract

Crohn disease is a chronic, transmural, inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract with unknown etiology. It can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract and may cause fistula, stricture, or abscess formation with disease progression. The preoperative diagnosis and definite management of this rare complication are challenges for physicians, urologists, and surgeons.

Key words: Crohn disease, Intestinal fistula, Urinary bladder fistula

The incidence of enterovesical fistula in Crohn disease was reported to range from 2% to 5%.1-4 The prevalence of Crohn disease in Asian populations is lower than in Western populations. Only 2 studies written by Japanese and Korean authors reported on the clinicopathologic characteristics of enterovesical fistula in Crohn disease.5,6 This article will illustrate the features of Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula in Taiwan, the effectiveness of available diagnostic modalities, and the outcomes of managements.

Patients and Methods

In our retrospective study, we identified patients with both Crohn disease and enterovesical fistula from January 1993 to May 2010 who were treated at the National Taiwan University Hospital. We searched for and identified patients with ICD-9 diagnosis codes of Crohn disease (555 and 556). All of the patients diagnosed with Crohn disease were confirmed with endoscopic biopsy. The medical records of these patients were reviewed thoroughly. The existence of the enterovesical fistula was confirmed by at least one of the following diagnostic modalities, including cystoscopy, colonoscopy, cystography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging. The age and sex of the patient, clinical presentations, locations of the fistula, diagnostic modalities, treatments, and outcomes were recorded and analyzed.

Results

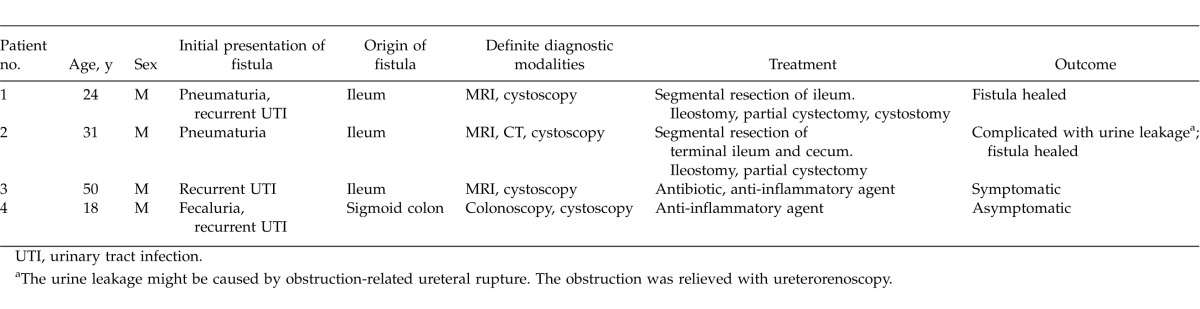

The characteristics of Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics in Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula

Epidemiology

A total of 92 patients with Crohn disease were identified in our study. A total of 11 of these 92 patients had fistula formation. The incidence of fistula formation was 11.9%. Among the 11 patients with fistula, 6 patients had enterocutaneous fistula, 4 patients had enteroenteral fistula, and 4 patients had enterovesical fistula. One patient had both enterocutaneous fistula and enteroenteral fistula. Of the patients with enterovesical fistula, 2 had concurrent ileoileal fistula. The incidence of enterovesical fistula in our Crohn disease patients was 4.3%. The mean age of these 4 patients was 30.75 years, and all patients were male. The origins of the enterovesical fistula, confirmed by laparotomy or imaging studies, were the ileum (n = 3) and the sigmoid colon (n = 1). The urinary bladder openings of the fistula were located at the dome in 3 patients and the posterior wall in 1 patient, as documented by cystoscopy.

Clinical presentations

The initial presentations in these 4 patients with both Crohn disease and enterovesical fistula were evaluated. Recurrent urinary tract infection, which was defined as at least 2 episodes of urinary tract infections within 6 months, was the most common reason for referral to our urologic clinic for further evaluation (n = 3; 75%). Each episode was accompanied by fever, dysuria, urinary frequency, or urinary urgency, and was also confirmed with pyuria in urinalysis or pathogen growth in urine culture. The other specific presentations included pneumaturia (n = 2; 50%) and fecaluria (n = 1; 25%).

Diagnostic modality

If symptoms implied the occurrence of enterovesical fistula, further examinations were necessary for definite diagnosis. Cystography and colonoscopy were performed in the 4 patients but showed fistula in only 1 patient. All 4 patients underwent cystoscopy and showed suspicious fistula opening in the urinary bladder. The openings were located at the dome in 3 patients and the posterior wall in 1 patient. CT was performed in 3 patients but showed fistula with the aid of barium enema only in 1 patient (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging with concurrent cystography was performed in 3 of the 4 patients, and fistula was visualized in all 3 of these patients (Fig. 2). The specimens of the 2 patients undergoing partial cystectomy and segmental resection of the bowel showed dense lymphoplasma cell infiltration involving nearly the whole layer of intestines (Fig. 3), suggestive of Crohn disease.

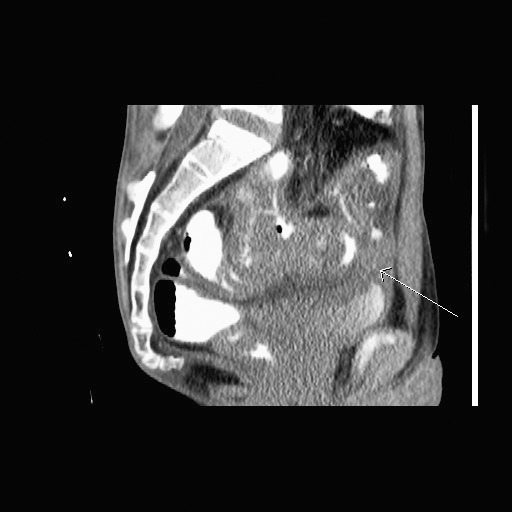

Fig. 1.

Upper gastrointestinal barium meal study followed by CT scan (sagittal view). The enterovesical fistula was indicated with an arrow.

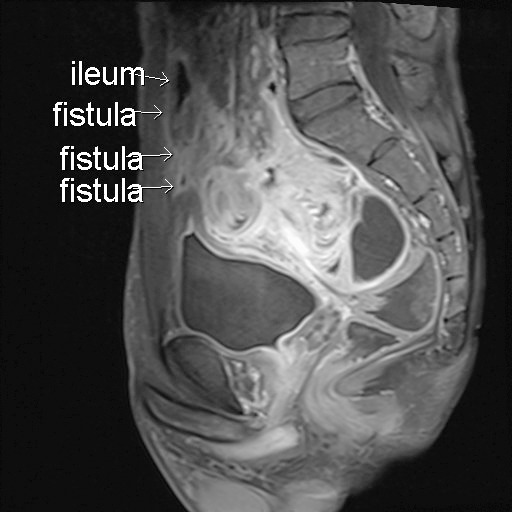

Fig. 2.

MRI of the pelvis (sagittal view). The fistula tract was shown more clearly than with CT scan.

Fig. 3.

Resected ileum (right) and partial urinary bladder (left). Because of severe adhesion, diseased ileum and part of the urinary bladder were resected with a segment of normal ileum.

Treatments and outcomes

Medial treatment

The standard medical treatment of Crohn disease is 5-aminosalicylates agents or corticosteroids. All patients had been treated with mesalazine. A total of 2 of the 4 patients chose conservative treatment with medications. One still suffered from recurrent urinary tract infection. The other had received regular injections of adalimumab, an anti–tumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibody, every 2 weeks for 3 years. There was no evidence of fistula recurrence in follow-up imaging studies.

Recurrent urinary tract infection is a complication of enterovesical fistula. The admission dates for febrile urinary tract infection were recorded as October 2009 and December 2009 in patient 1, August 2009 and October 2009 in patient 3, and June 2009 and July 2009 in patient 4. All urine cultures grew Escherichia coli. For patients with symptomatic afebrile urinary tract infection or asymptomatic persistent pyuria, ciprofloxacin was the preferred empirical oral antibiotic.

Surgical treatment

Two patients underwent segmental resection of diseased bowel and partial cystectomy. Loop ileostomy was also performed in both patients. Right hydronephrosis developed in 1 patient postoperatively. Cystography showed no urine leakage at the urinary bladder, but intravenous urography revealed urine leakage at right lower ureter (Fig. 4). The oblique line on the image over the right pelvis to the left upper abdomen is a Jackson-Pratt drain tube. The contrast medium leaked from the ureter and was drained via the tube. The extravasation might have been caused by obstruction-related ureteral rupture. Percutaneous nephrostomy was initially performed for urinary diversion. The obstruction was relieved with ureterorenoscopy, and a double-J ureteral stent (J-J ureteral stent) was inserted. The J-J ureteral stent was removed 3 months later for fear of encrustation on the stent. The follow-up renal ultrasonography showed no right-sided hydronephrosis. There was no immediate postoperative sepsis or death. Urine cytology, urinalysis, and urine culture are reasonable diagnostic tests for further evaluation if pneumaturia, fecaluria, or other lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection occur after surgery. There was no episode of urinary tract infection, suggesting recurrence of enterovesical fistula, or other complications in the follow-up times of 16 and 24 months in the 2 patients, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Intravenous urography performed after the surgery. The oblique line on the image over the right pelvis to the left upper abdomen is a Jackson-Pratt drain tube. The contrast medium leaked from the ureter and was drained via the tube.

Discussion

The incidence of enterovesical fistula in Crohn disease ranged from 2% to 5% in previous studies. This incidence probably refers to the rate for patients referred for fistula and then treated surgically. Even if this is not the case, it fits the suspicion that the true frequency of enterovesical fistula is lower, given that the data came from a tertiary referral center.6 This might explain the reason that the incidence (4.3%) in our study is relatively higher than those in associated studies.

The origins of most enterovesical fistulas are the ileum followed by the sigmoid colon. There is a tendency for enterovesical fistulas to coexist with other types of fistulas.1–4 A total of 3 patients (75%) had ileovesical fistulas, and 1 patient had sigmoid-vesical fistula in our small series. Two had concurrent ileoileal fistulas. This might be explained by the features of Crohn disease, which is a chronic transmural inflammatory disease with segmental lesions scattered in both the small intestine and colon.

The male to female ratio of enterovesical fistula in Crohn disease was 2–3:1, as reported in previous studies.3,4,6 However, Crohn disease is predominant in women. In our institution, a total of 58 men and 34 women with Crohn disease were identified, and the male to female ratio was close to 2:1. No reverse male to female ratio of Crohn disease in Asian counties was reported. All of the patients with both enterovesical fistula and Crohn disease in our series were men. It is generally accepted that the uterus, lying between the bowel and urinary bladder, may act as a barrier, protecting the urinary bladder from diseases of the bowel and decreasing the chance of enterovesical fistula formation in women.7,8

It might be assumed that enterovesical fistulas would by their nature be obviously symptomatic, and all patients in our series were symptomatic. It is surprising that some patients with enterovesical fistula did not present with any urinary symptoms in earlier literature, which suggests that patent fistulas need not necessarily result in continual communication or lead to inevitable urinary tract infection.6 The enterovesical fistulas in these asymptomatic patients were found incidentally during the laparotomy for other types of fistula formation. The stage of the fistula formation may be too early to be detected by preoperative investigations.

The leading initial presentations in Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula were recurrent urinary tract infection and pneumaturia. Fecaluria and hematuria were less common.4,6 The incidences of above symptoms in our series were 75% (n = 3) in recurrent urinary tract infection, 50% (n = 2) in pneumaturia, and 25% (n = 1) in fecaluria. The data were compatible with Yamamoto and Keighley's series,6 which revealed the leading 2 symptoms in symptomatic Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula as pneumaturia (18 of 22; 81.8%) and urinary tract infection (7 of 22; 31.8%). Saint-Marc et al4 also suggested that any patient with Crohn disease and a history of pneumaturia or man with recurrent urinary tract infections must be assumed to have an enterovesical fistula until proven otherwise. Urine leakage to the anus was much less common. This might be related to higher intraintestinal pressure, compared with the lower intravesical pressure.

Despite clinical presentations being highly suspected to be related to enterovesical fistula, the diagnosis cannot be made without imaging studies. The preoperative diagnosis is a challenge for physicians, urologists, and surgeons. Kovalcik et al9 reported that the preoperative diagnostic rate was 45%. The patient had to undergo many radiologic and endoscopic studies for definite diagnosis, and only a few of the studies revealed the existence of fistulas. Urine cytology for fecal materials and cystoscopy for fistula opening were recommended as first-line investigations because of their higher positive rates.10 The reported positive rates were 86% and 89%, respectively. A typical cystoscopy finding was a bullous edema surrounded by a localized patch of inflammation associated with inflammatory polyps. We did not perform urine cytology but did perform cystoscopy in all 4 patients. The positive rate was 100% for cystoscopy in our series.

Among other studies, such as cystography, upper gastrointestinal and lower intestinal series, panendoscopy, and colonoscopy, the CT scan, with a positive rate of 55% to 66.3%, was recommended as the subsequent study.5,10 Schmidt et al11 also reported a 77.2% accuracy rate with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for fistula detection in patients with complicated inflammatory bowel conditions. Of the 4 patients in our series, 1 patient received cystoscopy and colonoscopy only because both tests revealed the existence of the fistula. The other 3 patients received all of the above studies. CT scan diagnosed fistulas in 1 of the 3 patients (33.3%). MRI can visualize fistulas in 3 of 3 patients (100%), but colonoscopy can only detect fistula in 1 of 4 patients (25%). Cystography, intravenous pyelography, and upper gastrointestinal and lower intestinal series failed to identified any fistulas in our series.

The general surgical options for enterovesical fistula included 1-stage, 2-stage, and 3-stage surgery. The 3-stage surgery included enteric diversion in the first session, followed by resection of diseased bowel and anastomosis, and finally the closure of the enteric diversion. The 2-stage surgery combined enteric diversion, resection of diseased bowel, and primary anastomosis in 1 session, followed by closure of the enteric diversion. The 1-stage surgery combined all of the procedures in 1 session. We performed the 2-stage surgery in 2 patients who underwent surgical treatment. The outcomes of bypass surgery in Crohn disease patients with enterovesical fistula were very bad in the early literature, and the 3-stage surgery has never been a surgical option.4 A total of 3 of 3 patients in the study had unhealed fistulas and persistent sepsis, and all died. Two- or one-stage surgery is the mainstay in surgical treatment. If the patient is on long-term steroids, has poor nutritional status, or has an abscess or multiple fistulas, then anastomosis protected by a loop ileostomy is preferred.6 The other types of fistula and intra-abdominal abscess were frequently found incidentally during laparotomy with the incidences of 32% and 20% to 49%, respectively. Both of our 2 patients had concurrent ileoileal fistulas.

Whether to close the bladder defect at the time of operation is controversial. Partial cystectomy with primary closure of urinary bladder defect was performed on our two patients due to severe and diffuse adhesion between diseased bowels and the urinary bladder. In the case series by Yamamoto and Keighley6 and Saint-Marc et al,4 none of their patients had to receive partial cystectomy, and the defects were closed with sutures. McNamara et al3 claimed that the closure of the urinary defect was not necessary in his series because there was no occurrence of urine leakage postoperatively. However, in the studies by Yamamoto and Keighley6 and Saint-Marc et al,4 mortality and recurrence occurred in cases where the fistula tracts were not found and were closed. Thus, it is reasonable to close the defect in the urinary bladder.

There was no immediate postoperative sepsis or mortality in our series. This may be due to less comorbidity in young patients. Right-sided hydronephrosis developed in 1 patient because we oversewed the ureteropelvic junction during the closure of the urinary bladder defect. No similar complication was reported previously. This might be related to the larger defect caused by partial cystectomy. Ureteral catheter insertion before laparotomy may prevent the event. The overall complication rate ranged from 8% to 12% in previous studies. The presence of sepsis and multiple fistulas increases the incidence of postoperative complications. The recurrence rate of enterovesical fistula was reported to range from 0% to 13%. In our series, no recurrence was noted, with a follow-up time of at least 16 months.

Conclusion

If pneumaturia or recurrent urinary tract infection occurs in patients with Crohn disease, enterovesical fistula should be highly suspected. Cystoscopy and urine cytology are appropriate first-line investigations. CT scan and MRI also have good diagnostic rates as second-line investigations. One- or two-stage surgery with urinary bladder defect closure is the surgical treatment of choice.

References

- 1.Talamini MA, Broe PJ, Cameron JL. Urinary fistulas in Crohn's disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;154(4):553–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle J. Involvement of the urinary tract in Crohn's disease. In: RN Allan, Keighley MRB, Alexander-Williams J, Hawkins CF., editors. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone;; 1990. pp. 483–488. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara MJ, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Weakley FL, Farmer RG. Surgical treatment of enterovesical fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(4):271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02055467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saint-Marc O, Frileux P, Vaillant JC, et al. Enterovesical fistulas in Crohn disease: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Chir. 1995;49(5):390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon YS, Yu CS, Yang SK, Yoon SN, Lim SB, Kim JC. Intra-abdominal fistulas in surgically treated Crohn's disease patients. World J Surg. 2010;34(8):1924–1929. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto T, Keighley MR. Enterovesical fistulas complicating Crohn's disease: clinicopathological features and management. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15(4):211–215. doi: 10.1007/s003840000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West CF., Jr Vesico-enteric fistulas. Surg Clin North Am. 1973;53(3):565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang CY, Pu YS, Chen J, Tsai TC, Lai MK. Clinical characteristics and management of enterovesical fistulas. J Urol ROC. 1998;9(3):138–142. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovalcik PJ, Veidenheimer MC, Corman ML, Coller JA. Colovesical fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 1976;19(5):425–427. doi: 10.1007/BF02590828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels IR, Bekdash B, Scott HJ, Marks CG, Donaldson DR. Diagnostic lessons learnt from a series of enterovesical fistulae. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4(6):459–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt S, Chevallier P, Bessoud B, Meuwly JY, Felley C, Meuli R, et al. Diagnostic performance of MRI for detection of intestinal fistulas in patients with complicated inflammatory bowel conditions. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(11):2957–2963. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0669-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]