Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the relationship between stage of change (SOC) and behavioral outcomes among African American women entering obesity treatment in two settings. Fifty-five overweight/obese (body mass index = 26.50–48.13), but otherwise healthy African American women, 23 to 56 years old, attended a 13-week weight loss–treatment program that took place at churches (n = 36) or a university (n = 19). Participants were weighed, completed SOC measures, and had a physical fitness test at pre- and posttreatment. Pretreatment measures of SOC placed 47% of the participants as actors, 31% as contemplators, and 22% as maintainers. Of the 45 women who reported posttreatment SOC, 7% regressed, 44% did not change, and 31% progressed in SOC. Pretreatment SOC predicted posttreatment weight loss in the church setting but not in the university setting. At churches, contemplators lost more weight than actors and maintainers. The church may be a more conducive setting for weight change behaviors for African American women who are categorized as contemplators in the SOC model.

Keywords: stages of change, African American women, obesity, weight loss

Traditionally, “being big” has been accepted in the African American community. In many respects, this attitude is psychologically healthy as far too many American women suffer from poor self-esteem and discrimination due to excess weight (Devlin, Yanovski, & Wilson, 2000; Wadden et al., 2006). Yet obesity has reached epidemic proportions and is threatening the quality of life and livelihood of many African American women and their families. As noted by the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, if we are to help African American women achieve and maintain healthier weights, we must change our research paradigms and weight management strategies (Kumanyika et al., 2007). Tailoring weight management paradigms and intervention strategies to African American women requires addressing the greater context in which eating and “being big” occurs rather than focusing on the individualistic energy balance strategies that have been the focus of weight management for nearly half a century (Kumanyika et al., 2007). The purpose of the present study was to apply the stages of change (SOC) model to examine what SOC African American women were in when entering a weight management program (WMP), whether SOC differed by treatment setting (university vs. church), and whether SOC was associated with treatment outcomes. This work was designed to begin to examine motivation to lose weight, a construct that is not well understood among African American women.

Being “Big” in the African American Community

Motivation to lose weight often differs by cultural group, partly as a function of differing views of body size and shape standards, acceptable weight, and attitudes toward obesity (Kumanyika, 1993). Traditional weight loss programs have focused on alterations in energy balance through changes in eating and exercise behaviors. Appearance, or more specifically a drive for thinness, a beauty characteristic among Caucasian women, often is the motivation underlying traditional weight loss programs. African American women tend to accept and appreciate larger body sizes and are less likely to view themselves as overweight (Kumanyika, Wilson, & Guilford-Davenport, 1993). Kumanyika (1993) writes that obesity may be “viewed positively (or less negatively) within cultures, families, or generations for which it is associated with physical robustness and with protection from hunger” (p. 652).

Historically, there have been high rates of overweight/obesity among African Americans, beginning as early as the National Health Examination Surveys of the 1960s (now the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey or NHANES). Current research estimates that nearly 80% of African American women are overweight with 50% of these women classified as obese and subsequently at much higher risk for weight-related problems (Wang, Beydoun, Liang, Caballero, & Kumanyika, 2008). This statistic is alarming because of the disproportionate obesity-related morbidity and mortality suffered by African American women, which includes type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, hypercholesterolemia, and some forms of cancer (Center for Disease Control, 2007; World Health Organization, 2006).

Applying SOC to Understand Weight Loss Patterns

The SOC model has been applied to weight loss in a variety of contexts (Dallow & Anderson, 2003; Finckenor & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2000; Fowler, Follick, Abrams, & Rickard-Figueroa, 1985; Greene et al., 1999; Greene & Rossi, 1998; Greene, Rossi, Reed, Willey, & Prochaska, 1994; Prochaska, Norcross, Fowler, Follick, & Abrams, 1992; Riebe et al., 2005). Although less research has been done with African American populations and the SOC model, it has been shown to be useful in understanding behavior change in nutrition (Hargreaves et al., 1999; Hawkins, Hornsby, & Schorling, 2001). For instance, African American women who reported a desire to reduce their dietary fat intake (i.e., in the action stage) reported less dietary fat intake than women who were not trying to change (precontemplators and contemplators; Hargreaves et al., 1999). According to the SOC model, individuals pass through a series of stages as they attempt behavior change (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), including precontemplation (no intent to change in the next 6 months), contemplation (intend to change in the next 6 months), action (actively making changes), and maintenance (maintaining changes). Yet it is unclear how individuals move through the SOC in WMPs, how movement in the SOC affects outcomes, or whether SOC is useful in understanding behavior change among African American women in WMPs. A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association highlights the need for more evidence regarding the SOC paradigm for intervention trials aimed at dietary changes (Artinian et al., 2010).

Despite the higher rates of obesity and related health conditions, African American women are less likely to enter and are less successful in traditional WMPs (McTigue et al., 2003; West, Prewitt, Bursac, & Felix, 2009; Wing & Anglin, 1996), which often were developed for and with Caucasian populations. This limited success of WMPs for African American women has prompted some (Kumanyika, 2008; Seo & Sa, 2008) to propose gathering more data about how African American women make behavior changes in WMPs as well as how to adapt such programs to meet their needs. Rather than focus only on the outcome of weight loss, the aim of this study was to include relevant psychosocial and contextual factors that influence day-to-day decision making among African American women, which Kumanyika et al. (2007) have identified as a crucial aspect of research paradigms conducted within African American communities.

Tailoring behavioral treatments, such as WMPs, based on the individual’s SOC has produced more effective outcomes than unmodified programs in areas such as nutrition and exercise among Caucasians (Dallow & Anderson, 2003; Finckenor & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2000; Greene et al., 1994; Greene & Rossi, 1998). In addition to the literature on the SOC model and weight loss, we were motivated to examine this model in the context of our work with African American women and weight loss. It has been suggested that individuals in the action and maintenance stages who enter treatment programs may have the most difficulty in adopting alternative belief and behavioral strategies suggested by the treatment program (Finckenor & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2000; Kinnaman, Bellack, Brown, & Yang, 2007; Logue et al., 2004; Pantalon, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2002).

In our decade of work with African American women, we have observed many women who enter the program already in action or maintenance and suspected that, as a group, these women tended not to do as well. They generally had their own ideas about what they needed to do and were less likely to engage in the new behaviors and thinking. By definition, actors and maintainers can make only minimal progress through the SOC, creating a ceiling effect which may detrimentally affect their attempts at cognitive and behavior changes. Because behavioral WMPs for African Americans typically are minimally effective in the long term, understanding how SOC may help or hinder progress in treatment is relevant and timely.

For example, individuals with dieting history who have been successful at losing weight in the past may have beliefs or cognitions regarding types of foods that “should” or “should not” be eaten to lose weight, such as avoiding carbohydrates. Additionally, individuals entering WMPs in the action or maintenance stages may be engaged in disadvantageous actions including skipping breakfast or cycles of extreme calorie restriction followed by high-calorie intakes, termed binge episodes. Such actions may provide short-term, rapid weight loss thus reinforcing these thought and behavior patterns; however, more difficult and perhaps more important is achieving long-term, moderate weight loss. With these beliefs and behaviors firmly entrenched in actors and maintainers, asking them to adopt new actions, such as increasing exercise frequency and duration, eating frequent, small meals, or some combination thereof, may be more difficult. If individuals are reluctant to make new behavior changes, then they may be at increased risk for relapse to old behavior patterns (Prochaska et al., 1994) and weight regain.

Despite the high prevalence of obesity and comparatively low success of WMPs among African American women, little empirical work has examined the utility of SOC for behavior change (Hargreaves et al., 1999; Hawkins et al., 2001; Walcott-McQuigg & Prochaska, 2001). There is evidence that older African Americans in the action or maintenance stages for exercise were more likely to endorse exercise as part of their perceptions of a “healthy individual.” Furthermore, they viewed social support as essential to initiating and maintaining regular exercise. Hawkins et al. (2001) reported a correlation between body mass index (BMI) and SOC such that actors and maintainers had lower BMIs compared with individuals in earlier stages.

The extant literature on the utility of SOC among African Americans clearly is limited. The current study specifically examined how movement through the SOC was related to weight loss among a sample of African American women in our clinical trial of Behavior Choice Treatment (BCT; Sbrocco, Hsiao, & Osborn, 2007), a WMP for African American women. BCT has been successful at improving weight loss outcomes in African Americans by conducting the program in community-based settings such as African American churches (Kennedy et al., 2005; Kumanyika & Charleston, 1992; McNabb, Quinn, Kerver, Cook, & Karrison, 1997; Sbrocco et al., 2005), which often provide both instrumental and emotional social support (Davis, Clance, & Cailis, 1999). The historical distrust of research among African Americans (Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St. George, 2002) also may be ameliorated when church leaders endorse a program. Given the importance of church in the African American community and that some treatment groups occurred in a church setting, it was important also to assess the role of spirituality in any change noted among participants.

BCT was designed to promote long-term exercise and diet changes to produce moderate, sustainable weight loss. It was expected that contemplators would demonstrate increased weight loss and fitness compared with actors and maintainers as they would be more accepting of behavior change across settings. It also was hypothesized that the church setting would be more conducive to helping African American women progress through the SOC than the university setting, and therefore church participants would have increased weight loss and fitness.

Method

Participants

Participants were 55 African American women, aged 18 to 55 years, who were enrolled in a weight management treatment outcome study designed for African American women (Sbrocco et al., 2007). The overall sample consisted of middle-age (M = 40.44 years, SD = 9.08), obese (BMI M = 35.49, SD = 5.06) African American women (100% African American), who mostly were married (43.6%) or single (32.7%), employed full-time (94.5%), and college educated (64.1%). Based on pretreatment cycle ergometry fitness testing VO2max categorizations, 85% of the sample was classified into the poor or very-poor range.

Nineteen (35%) participants completed the weight management study at predominantly African American churches in the metropolitan Washington, D.C. area, and 36 (65%) completed the WMP at a medical school in the metropolitan Washington, D.C. area. Consent was obtained from all participants prior to treatment and the procedures of the study were approved by the university institutional review board.

Assessments and Measures

Anthropomorphic measures

Weight in pounds (lbs) was measured at pretreatment, weekly meetings, and posttreatment. The percent difference between pretreatment and posttreatment ([pretreatment weight − posttreatment weight] ÷ pretreatment weight) was calculated to determine posttreatment weight loss. Height to the nearest quarter inch (in.) was measured at pretreatment. BMIs (calculated as kilograms per meter squared) were calculated after a conversion of both pounds and inches to their metric equivalents.

Demographic information

Demographic information was assessed using a self-report questionnaire created for the ongoing treatment outcome study. The questions were formatted as either check the box or fill in the blank, and included the following questions: for race, participants checked one or more boxes (African American, White, African, Hispanic, West Indies/Caribbean, American Indian or Alaska, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Other, or No response); age (fill in the blank); employment status (part-time, full-time, retired, disabled, homemaker, or unemployed); level of education (some high school, GED, graduated high school, attended/graduated college, or attended/graduated graduate school); and marital status (single, cohabitating, married, separated, divorced, or widowed).

Treatment adherence

Session attendance was calculated by assigning one point for each measured weight of each participant, recorded weekly throughout the treatment program. Valid weight data at every time point (pretreatment and the 13-week group meetings) would constitute perfect attendance and a total score of 14. No participant attended less than half the sessions and 13 (24%) of the 55 participants had perfect attendance. The average number of sessions attended was 12.27 (SD = 1.60), with a mode of 12 and a median of 11.

SOC categorization

A four-item SOC algorithm was used to assess SOC classification for weight loss intentions and activities (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). The combination of responses on four yes/no questions results in placement into precontemplation, contemplation, action, or maintenance stage of change. According to the SOC model, participants who answer “No” to two or three of the four questions are contemplators. Maintainers are distinguished from actors because they have maintained active changes for the previous 6 months. Although no gold standard exists for categorization methods using the SOC model (Brug et al., 2005), the method used here has been reported to be reliable across varying problem behaviors in participants of unreported ethnicity (Marcus, Selby, Niaura, & Rossi, 1992; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1992). The SOC questionnaire is valid when used with exercise behavior such that self-reported SOC differed significantly and meaningfully in relation to self-reported exercise behavior of male police officers of unreported ethnicity (Hausenblas, Dannecker, Connaughton, & Lovins, 1999). In our data, the SOC questionnaire, including all assessed time points, produced a reliability K-R 20 coefficient of .69. Cronbach’s α of .70 is an acceptable value of alpha coefficient (Litwin, 1995).

Physical fitness

The progressive submaximal exercise cycle test, protocol B, on a bicycle ergometer was used (Lockwood, Yoder, & Deuster, 1997) to estimate participant’s physical fitness level (VO2max) at pretreatment and posttreatment. Church participants were required to visit the university to partake in this fitness assessment, whereas university participants completed the assessment before or after the pretreatment and posttreatment treatment sessions. During the assessment, participants sat on a stationary bicycle, were connected to a heart rate monitor and a two-way respiratory valve, and pedaled at 50 revolutions per minute. Initially, they warmed up at 25 watts. After 2 minutes, the work rate was set at 50 watts and was increased every 2 minutes to 75, 100, and then 150 watts. VO2max was calculated by measuring participants’ heart rates and expired air samples during the last 30 seconds at each work load and then predicting VO2max by extrapolation of the heart rate and oxygen uptake at each submaximal workload (Fitchett, 1985). The accuracy of such protocols and VO2max predictions have been found to provide accurate estimations of cardiorespiratory fitness while requiring less exertion than maximal fitness tests (George et al., 2000), which may not be suitable for all individuals. Participants received feedback on their calculated fitness level categorized as very poor, poor, fair, good, excellent, or superior based on age-adjusted cutoffs at pretreatment and posttreatment based on established norms. For women between the ages of 40 and 49 years, scores (in mL/kg/min) below 21 are considered very poor, 21.0 to 24.4 are poor, 24.5 to 28.9 are fair, 29.0 to 32.8 are good, 31.5 to 35.7 are excellent, and above 36.9 are superior (The Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research, 1998).

Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale (SIBS)

The SIBS was used to assess actions and beliefs related to spirituality (Hatch, Burg, Naberhaus, & Hellmich, 1998). The SIBS contains 26 items in a modified Likert-type format (strongly agree, agree, neutral) and has demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability (.92). Concurrent construct validity of the SIBS has been determined by correlating total score on the SIBS with total score on an established spirituality scale, The Spiritual Well Being Scale (r = .80), and internal validity was assessed by determining the coefficient alpha (α = .92); however, these validity indicators were performed on a sample of unreported ethnicity from a rural family practice clinic (Ellison & Paloutzian, 1982; Hatch et al., 1998). The SIBS utilizes wording aimed at being inclusive of many different religious traditions. An example question on this scale is “Some experiences can be understood only through one’s spiritual beliefs.” Levels of spirituality and beliefs were classified using tertiles of scores. Participants low in spirituality scored between 29 and 65, moderate spirituality between 66 and 73, and high spirituality between 74 and 110 (the highest score) on the SIBS.

Procedure

Data were gathered from a series of behavioral weight management groups conducted during 2001–2003. Prior to the weight management groups, participants engaged in a 2-week orientation (pretreatment) period where they were asked not to change their diet or exercise habits but were asked to track their eating and exercise behaviors “as-is” using computerized food diaries (i.e., a Palm Pilot with food diary software was provided to each woman). Participants completed anthropomorphic measures (e.g., weight, height), the demographic questionnaire, and the SOC and SIBS questionnaires at pretreatment. They then participated in a 13-week, 90-minute behavioral weight management group, conducted either in a university or in predominantly African American churches and co-led by a clinical psychologist and a psychology doctoral student. Participants continued to use the food diaries to track their food intake during the first 11 weeks of the group. By BCT design, participants are purposely asked to stop monitoring food intake during the last few weeks of group in order to simulate the end-of-group meetings and thus use group time to solve difficulties encountered when they stop monitoring their food intake. Sessions focused on adopting a healthy lifestyle such as consuming a moderate calorie diet, eating more fruits and vegetables, exercising at least 30 minutes a day most days of the week, and examining and altering attitudes toward eating and exercise. At posttreatment, participants again completed the SOC questionnaire and anthropomorphic measures. Participants were financially compensated for successful completion of the necessary items.

Analyses

A series of analyses of variance were run separately for posttreatment percent of weight loss and physical fitness level (VO2max). Pretreatment scores were entered as covariates in the analyses for posttreatment physical fitness level. Specifically, effects of pretreatment stage of change (contemplation, action, and maintenance) or stage progression (no change vs. progress) were entered as main effects in separate analyses, along with their interaction with treatment setting (university vs. church). Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted and alpha was adjusted using the conservative Scheffe’s test due to the high number of comparisons made from comparisons of SOC groups in each setting.

Results

General Sample Characteristics

The majority of the participants were classified as actors (n = 26 or 47%), followed by contemplators (n = 17 or 31%) and then maintainers (n = 12 or 22%) at pretreatment. The percentage of actors at pretreatment in the current study was higher than that reported in other WMPs and exercise intervention studies, where the percentage of actors has been estimated to range from 9% to 25% (Hausenblas, Dannecker, & Downs, 2003; Laforge, Velicer, Richmond, & Owen, 1999). It is possible that stage categorization methods (e.g., using a single question to assign SOC categorization) as well as differences between individuals who are seeking treatment as opposed to survey respondents could account for some of this variation, since by definition, actors may be more likely to seek treatment. There was no significant difference between university and church participants in pretreatment SOC, χ2(2, 55) = 2.18, p = .34.

At pretreatment, across treatment settings, pretreatment contemplators, maintainers, and actors were not significantly different in weight, BMI, age, marital status, number of sessions attended, or VO2max. Additional demographic and pretreatment anthropomorphic data separated by groups are presented in Table 1. Collapsing across pretreatment SOC groups, participants treated in church setting, M = 41.11 years, SD = 9.88, were significantly older that participants in the university setting, M = 40.08 years, SD = 8.75, F(1, 45) = 4.81, p < .05. Church participants, M = 33.33, SD = 3.87, also had a lower BMI compared with university participants, M = 36.64, SD = 5.32, F(1, 49) = 5.42, p < .05. There were no other significant pretreatment differences between treatment settings. No interaction effect of pretreatment SOC and treatments setting was found in any of the pretreatment characteristics. For descriptive purposes, Table 2 presents correlations between the continuous variables in the study. As would be expected, the number of sessions attended was positively correlated with percent weight lost and VO2max change through posttreatment. The SIBS total score also was positively correlated with BMI.

Table 1.

Pretreatment Demographic and Anthropomorphic Characteristics by SOC and Setting

| University (N = 36) | Church (N = 19) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contemplators (n = 13) |

Actors (n = 17) | Maintainers (n = 6) | Contemplators (n = 4) |

Actors (n = 9) | Maintainers (n = 6) |

|

| Age (M ± SD years) | 37.08 ± 9.26 | 40.35 ± 8.09 | 45.83 ± 7.52 | 47.50 ± 6.14 | 36.67 ± 10.17 | 43.50 ± 9.40 |

| Education (%) | ||||||

| High school | 0.00 | 17.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| College | 58.33 | 52.94 | 60.00 | 50.00 | 66.67 | 66.67 |

| Graduate school | 41.67 | 29.41 | 40.00 | 50.00 | 33.33 | 33.33 |

| BMI (M ± SD) | 38.87 ± 4.37 | 35.26 ± 5.38 | 35.75 ± 6.29 | 33.32 ± 6.39 | 34.09 ± 3.79 | 32.20 ± 1.93 |

| Number of sessions attended | 11.08 ± 2.14 | 10.53 ± 1.70 | 11.84 ± 1.17 | 12.25 ± 0.50 | 11.78 ± 0.97 | 11.83 ± 0.75 |

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 19.92 ± 3.76 | 21.64 ± 5.79 | 19.39 ± 3.50 | 18.62 ± 3.86 | 19.92 ± 4.02 | 19.90 ± 4.33 |

Note: High school = attended and/or graduated high school; college = attended and/or graduated college; graduate school = attended and/or graduated graduate school; SOC = stage of change; BMI = body mass index.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations for Age, BMI, Weight Change, VO2max Change, SIBS Total Score, and Attendance

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | |||||

| 2. Pre-tx BMI | −0.09 | — | ||||

| 3. Percent wt lost by post-tx | 0.24 | 0.13 | — | |||

| 4. %VO2max change | −0.09 | 0.12 | 0.42** | — | ||

| 5. Pre-tx SIBS | 0.12 | 0.28* | −0.15 | −0.07 | — | |

| 6. Number of sessions attended | 0.32* | −0.19 | 0.38** | 0.35* | −0.32 | — |

Note: BMI = body mass index; SOC = stage of change; Wt = weight; tx = treatment; SIBS = The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale from Hatch et al. (1998).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Participants’ progression through SOC during treatment was examined. Table 3 presents data on the 45 participants who reported SOC at the end of the treatment, of which 4 (7%) participants regressed one stage, 24 (44%) did not change stage, and 17 (31%) progressed at least one stage. Of the 10 participants who did not complete the posttreatment SOC questionnaire, 3 were contemplators, 3 were actors, and 4 were maintainers at pretreatment. SOC progression did not vary by treatment setting, χ2(3, 45) = 1.65, p = .65. When excluding participants who regressed (n = 4), SOC progression remained the same across treatment settings, χ2(2, 45) = 0.73, p = .69.

Table 3.

Stage Progression Through Posttreatment by Pretreatment SOC and Treatment Setting

| Pretreatment SOC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttreatment SOC | Contemplator | Actor | Maintainer | |

| University | Contemplator (n = 11) | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Actor (n = 15) | 0 | 13 | 2 | |

| Maintainer (n = 5) | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Church | Contemplator (n = 3) | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Actor (n = 8) | 0 | 6 | 2 | |

| Maintainer (n = 3) | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

Note: SOC = stage of change. N = 45 includes only participants who reported posttreatment SOC.

Pretreatment Stage of Change and Treatment Outcomes

An analysis of variance by pretreatment SOC group (contemplators, actors, and maintainers) and treatment setting (university vs. church) was conducted for percent weight loss and posttreatment VO2max, which can be seen in Table 4. Pretreatment VO2max was included as a covariate in the physical fitness analyses.

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance (or Covariance) of Posttreatment Outcomes by Pretreatment SOC Group and Treatment Setting: Estimated Mean and Standard Error

| University | Church | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contemplators (n = 4) |

Actors (n = 9) |

Maintainers (n = 6) |

Contemplators (n = 13) |

Actors (n = 17) |

Maintainers (n = 6) |

|

| Percent weight loss | 3.97 (1.24) | 2.93 (1.06) | 1.56 (1.84) | 7.35 (2.38)* | 1.12 (1.46)*,^ | −1.10 (2.38)^ |

| VO2max | 20.95 (1.06) | 20.12 (0.94)* | 19.33 (1.36) | 21.49 (1.67) | 23.26 (1.17)* | 23.04 (1.48) |

Note: SOC = stage of change. Numbers in the cell are estimated means and standard error produced by the analysis of variance model (for percent weight loss) or by the analysis of covariance model (for VO2max, when controlling for pretreatment scores).

For each outcome measure, numbers that have the same superscripts (* or ^) were significantly different at p < .05.

Weight loss

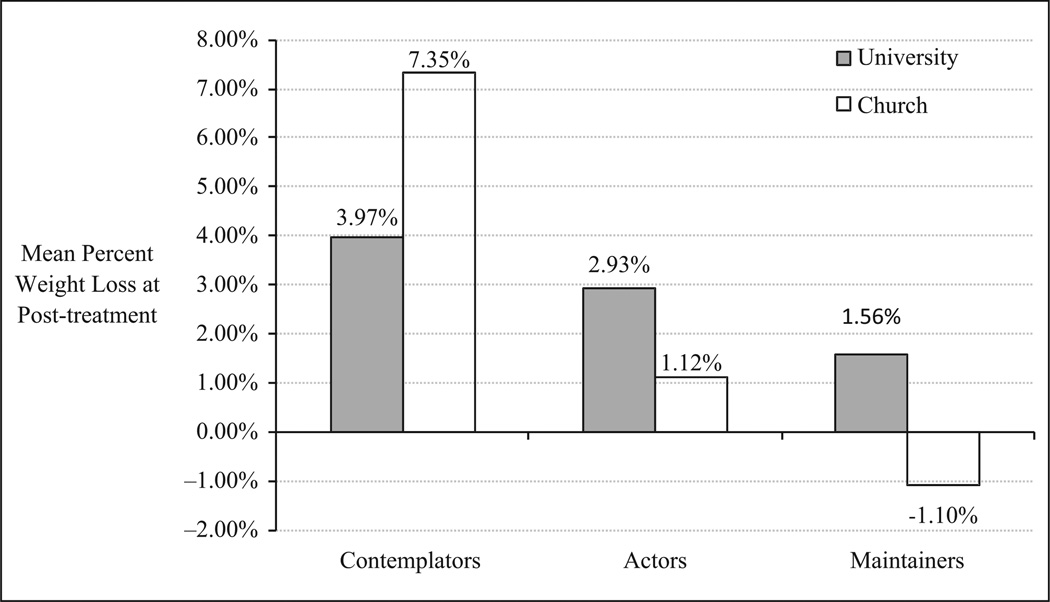

Overall, an analysis of variance indicated differences between SOC groups on percent body weight lost at posttreatment, F(2, 49) = 4.87, p < .05, η2 = .17. Percent weight loss did not differ by treatment setting, F(1, 49) = 0.19, p = .66, and there was no interaction of pretreatment SOC group by treatment setting, F(2, 49) = 2.13, p = .13. Pairwise comparisons using Scheffe’s correction revealed that contemplators, M = 4.77%, SD = 5.20, lost larger percentage of their body weight at posttreatment than actors, M = 1.96%, SD = 3.53, and maintainers, M = 1.50%, SD = 3.54. See Figure 1 for weight loss by pretreatment SOC and treatment setting. In the church setting, contemplators, M = 7.79%, SD = 4.70, lost a significantly larger percentage of their body weight at posttreatment compared with actors, M = 0.68%, SD = 2.64, p = .03, and there was a trend for contemplators to lose a larger percentage of weight than maintainers, M = 1.32%, SD = 4.89, p = .06. In the university setting, contemplators, actors, and maintainers did not significantly differ on percent weight loss at posttreatment.

Figure 1.

Percent weight loss by pretreatment stage of change and treatment setting

Physical fitness

Posttreatment VO2max levels did not differ by pretreatment SOC group, F(2, 39) = 0.11, p = .90, but they did differ by treatment setting such that university participants had lower cardiovascular fitness levels, M = 20.35 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 4.28, compared with church participants, M = 22.61 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 3.94, F(1, 39) = 5.44, p < .05. Post hoc tests revealed that the treatment setting difference in cardiovascular fitness levels only existed among actors such that actors at the university, M = 21.25 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 4.97, had significantly lower physical fitness level compared with actors at the churches, M = 23.33 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 2.18, F(1, 39) = 4.38, p < .05. There was no interaction effect of treatment setting and pretreatment SOC group, F(2, 39) = 0.77, p = .47.

Stage Progression and Treatment Outcomes

Results from an analysis of variance conducted for percent weight loss and VO2max by stage progression and treatment setting, controlling for pretreatment outcome scores can be seen in Table 5. Note that the analyses were conducted to compare only the group that had no change in SOC at posttreatment (no change group) and the group that had progressed at least one SOC by posttreatment (progress group). The group that regressed was not included in the analyses because of the small sample size (n = 4).

Table 5.

Analysis of Variance (or Covariance) of Posttreatment Outcomes by Pretreatment SOC Group and Treatment Setting

| University | Church | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No change (n = 17) |

Progress (n = 12) |

No change (n = 7) |

Progress (n = 5) |

|

| Percent weight loss | 2.73 (1.03) | 4.02 (1.23) | 0.31 (1.61) | 5.27 (1.91) |

| VO2max | 20.61 (0.85)* | 21.30 (1.10) | 23.65 (1.20)* | 22.00 (1.42) |

Note: SOC = stage of change. Numbers in the cell are estimated means and standard errors produced by the analysis of variance model (for percent weight loss) or by the analysis of covariance model (for the other outcomes, when controlling for pretreatment scores).

p < .05.

Weight loss

Percent weight loss at posttreatment significantly differed by stage progression, F(1, 35) = 4.11, p = .05. The group that progressed in SOC lost a significantly larger percentage of their body weight, M = 3.36%, SD = 4.37, compared with the group that did not progress in SOC, M = 2.02%, SD = 3.37. Post hoc tests revealed that only in the church setting, the progress group, M = 5.27%, SD = 5.13, lost a larger percentage of their body weight than the no change group, M = 0.31%, SD = 2.54, F(1, 35) = 5.31, p = .03, whereas in the university setting, there was no difference between the no change group, M = 2.73%, SD = 3.48, and the progress group, M = 2.41%, SD = 3.86, F(1, 35) = 0.05, p = .83.

Physical fitness

The no change group did not differ from the progress group in levels of posttreatment physical fitness, F(1, 30) = 1.04, p = .32, nor was there an interaction by treatment setting, F(1, 30) = 0.35, p = .56. Post hoc results showed that among the no change group, the university participants had lower fitness levels, M = 21.45 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 4.45, than the church participants, M = 23.69 (mL/kg/min) VO2max, SD = 2.38, F(1, 31) = 4.30, p = .05, whereas among the progress group, there was no difference by treatment setting, F(1, 31) = 0.16, p = .70.

Spirituality and beliefs

Participants were evenly distributed among low (31%), moderate (34.5%), and high (34.5%) categories of spirituality. There were no significant differences between spirituality and treatment setting, χ2 = 2.37, p = .31. In the church setting, 21% were classified as low in spirituality, 47% moderate, and 32% high. In the university setting, 36% were low, 28% moderate, and 36% high. There also was no significant association between spirituality and pretreatment SOC category, χ2 = 0.78, p = .91. Spirituality also did not affect percent weight loss at posttreatment, F(2, 54) = 1.20, p = .30.

Discussion

This application of the SOC model to overweight/obese African American women revealed that contemplators in the church setting lost a greater percentage of weight than both actors and maintainers through posttreatment. This finding contributes to the evidence that churches may be conducive environments for the delivery of behavioral treatment programs for African Americans (Kennedy et al., 2005; Ramirez, Chalela, Gallion, & Velez, 2007; Resnicow et al., 2002; Sbrocco et al., 2005). Given the success of contemplators in the church setting, a further understanding of their reasons for joining the program is important. Was it because others encouraged them or because the program is church sanctioned? Church environments may enhance contemplators’ success due to familiarity and the fact that the church provides an inviting social environment (Kennedy et al., 2005; Ramirez et al., 2007; Resnicow et al., 2002) where social support can play a vital role in behavior change (Dallow & Anderson, 2003; Prochaska, Norcross, et al., 1992). It is likely that contemplators, as compared with actors, are also more willing to seek and accept social support as they progress through the stages and decide whether or not to make behavioral changes (Vallis et al., 2003). Actors may need less support, be less willing to seek support, and be perceived by others as in need of less support for behavioral changes. Because many church members attend church on occasions outside of weekly treatment groups (e.g., Bible study), church-based groups have a built-in social support system that allows members to see each other, check in, and follow up on behavior changes.

Interestingly, our data did not support the notion that spirituality beliefs or actions were related to these outcomes. Rather, it may be that other factors in a church setting facilitate behavior change for contemplators. For example, allotting time for socializing prior to group programs or inviting family members to attend some of the treatment sessions may be key features as to why the church setting may be a particularly effective setting for treatment (Karanja, Stevens, Hollis, & Kumanyika, 2002). In the present study, we anecdotally observed greater social support among church members. Whereas individuals who attended the university often rushed into groups as they began and left as soon as the groups ended, individuals in the church setting were more likely to linger before and after group times. Additionally, many individuals in the church setting were involved in other activities at the church together as well, and often talked about checking in with one another during the week in between group meetings. The correlation between BMI and the SIBS was unexpected and difficult to discern. Future studies should focus on this relationship and additional variables that may account for the association (e.g., food consumption patterns; lifestyle factors).

In the present sample of African American women enrolled in a WMP, neither stage progression nor percent weight loss was affected by pretreatment differences between the SOC groups. Contemplators were more likely to progress through the stages than both actors and maintainers. By posttreatment, nearly three quarters of the pretreatment contemplators had progressed at least one stage. In support of our hypotheses, during the same timeframe, 71% of the pretreatment actors and maintainers had either stagnated or regressed.

The use of behavioral strategies emphasized in the present WMP apparently benefited the contemplators more than actors and maintainers. This finding is important in guiding researchers who wish to adapt and tailor WMPs for African American women. Understanding what stage women start a WMP may ultimately change the approach with which treatment is delivered. It may be that actors and maintainers have already integrated behavior change into their lifestyles (Kinnaman et al., 2007) and, therefore, may have more difficulty incorporating new approaches or behavioral changes than contemplators, who are more likely to be in malleable states. For example, individuals who have lost weight in the past using a certain weight control method (e.g., point-counting) may be reluctant to try different approaches, despite the fact that they have regained the previous weight lost. Contemplators, who may be more malleable to change, should be more likely to try a new approach. However, the importance of treatment setting and SOC should be considered.

The differences in how SOC affected weight loss by setting needs further exploration. Although the findings in the church setting were expected, we did not see the same results in the university setting. It is possible, and warrants future study, that social context of the church facilitated participation of individuals who may not generally be recruited through typical university recruitment procedures. Based on these findings, it is possible that contemplators should be considered to be context-specific rather than general. If SOC is more relevant in settings which facilitate social support, such as churches or existing community groups, then these findings may help improve such programs. Alternatively, if SOC does not effect change in more traditional weight loss settings and treatment programs, then continuing to explore factors that do promote change should be a focus of future work. It may be that an interaction between SOC and social support is key for African American women seeking to lose weight or make behavior change. Our findings warrant future research on clinical implications. For example, how do we further engage African American churches in weight loss efforts? Or, is it worthwhile for clinicians to include questions on the role of the church during intake assessments of African American patients’ biopsychosocial history?

Understanding how SOC can help tailor treatments for African Americans is important. For instance, understanding why African American women succeed or fail in WMPs or health behaviors such as exercise is critical. Women who are in the action or maintenance stages may have already started to make lifestyle changes and therefore may need different interventions than individuals in earlier stages. Our study provides a preliminary understanding of the SOC model as it relates to African American women’s attempts at behavior change for weight loss. However, African American women maintain respected and influential roles in family, religious, and social organizations and understanding a woman’s SOC could influence many spheres of their lives. We targeted SOC related to weight loss because many fundamental aspects of African American life and culture are centered on unhealthy dietary and physical activity patterns (Kumanyika et al., 2007; Kumanyika & Grier, 2006; Taylor, Poston, Jones, & Kraft, 2006); however it is likely that SOC could be applied to other critical life areas as well.

For example, it may help us understand a woman’s readiness to implement priority setting, stress management, or health care access and, therefore, ultimately could be applied to several life domains. Although we found evidence of a benefit for the church-based program, the mechanism producing the benefit could not be elucidated in the current study. We did not gather information addressing frequency of church attendance or the importance of church in the participants’ lives. Moreover, our study faced the same challenges that many community based research programs face. For example, we were unable to randomly assign individuals within our groups to one setting or another. The lack of control of such variables when conducting community research can lead to reduced strength and/or effectiveness of interventions according to traditional standards of clinical efficacy trials (Kumanyika et al., 2007). However, in African American communities where obesity rates are high, an understanding of individual and community-level factors that may influence both the measured outcomes (e.g., weight loss) is key if we are to develop a better understanding of this problem from the community perspective and develop effective prevention and intervention efforts to better the health of African Americans, particularly women, who suffer disproportionately from obesity-related health disparities (Kumanyika et al., 2007).

To date, few researchers (Finckenor & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2000; O’Connell & Velicer, 1988) have taken the SOC model into consideration when evaluating weight-loss treatment-seeking individuals. Fewer have applied the SOC model to overweight and obese African Americans in community settings (Hawkins et al., 2001; Suris, Trapp, DiClemente, & Cousins, 1998). However, as is often the case, the measures used have not been validated on African American populations and sample ethnicity was often not specified in previous research. Thus, whether the SOC algorithm is culturally equivalent among African Americans warrants further investigation. With this caveat, the unique contribution of this work is the provision of evidence that suggests SOC may be a useful construct among African Americans (whether it is culturally equivalent or not) and may be important in understanding motivations for weight loss.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was supported by a grant from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities P20 (P20 MD000505).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton P, Van Horn L, Lichtenstein AH, Burke LE. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:406–441. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brug J, Conner M, Harré N, Kremers S, McKellar S, Whitelaw S. The transtheoretical model and stages of change: A critique: Observations by five commentators on the paper by Adams, J. and White, M. (2004) Why don’t stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Education Research. 2005;20:244–258. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Prevalence of overweight, obesity and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–62 through 2005–2006. Washington, DC: Author; 2007. (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS] Health E-Stat) [Google Scholar]

- The Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research. The Physical Fitness Specialist Certification Manual. In: Heyward VH, editor. Advanced fitness assessment & exercise prescription. 3rd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallow CB, Anderson J. Using self-efficacy and a transtheoretical model to develop a physical activity intervention for obese women. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17:373–381. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.6.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NL, Clance PR, Cailis AT. Treatment approaches for obese and overweight African American women: A consideration of cultural dimensions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1999;36:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Yanovski SZ, Wilson GT. Obesity: What mental health professionals need to know. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:854–866. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.854. Retrieved from http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/157/6/854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CW, Paloutzian RF. The Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Nyack, NY: Life Advance; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Finckenor M, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Nutrition intervention group program based on preaction-stage-oriented change processes of the transtheoretical model promotes long-term reduction in dietary fat intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2000;100:335–342. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett MA. Predictability of VO2max from submaximal cycle ergometer and bench stepping tests. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1985;19:85–88. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.19.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JL, Follick MJ, Abrams DB, Rickard-Figueroa K. Participant characteristics as predictors of attrition in worksite weight loss. Addictive Behaviors. 1985;10:445–448. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(85)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JD, Vehrs PR, Babcock GJ, Etchie MP, Chinevere TD, Fellingham GW. A modified submaximal cycle ergometer test designed to predict treadmill VO2 max. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science. 2000;4:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- Greene GW, Rossi SR. Stages of change for reducing dietary fat intake over 18 months. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1998;98:529–534. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GW, Rossi SR, Reed GR, Willey C, Prochaska JO. Stages of change for reducing dietary fat to 30% of energy or less. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1994;94:1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)91127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GW, Rossi SR, Rossi JS, Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO. Dietary applications of the stages of change model. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99:673–678. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves MK, Schlundt DG, Buchowski MS, Hardy RE, Rossi SR, Rossi JS. Stages of change and the intake of dietary fat in African-American women: Improving stage assignment using the Eating Styles Questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch RL, Burg MA, Naberhaus DS, Hellmich LK. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale. Development and testing of a new instrument. Journal of Family Practice. 1998;46:476–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas HA, Dannecker EA, Connaughton DP, Lovins TR. Examining the validity of the stages of exercise change algorithm. American Journal of Health Studies. 1999;15:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas HA, Dannecker H, Downs DM. Examination of the Validity of a Stages of Exercise Change Algorithm. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:1179–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DS, Hornsby PP, Schorling JB. Stages of change and weight loss among rural African American women. Obesity Research. 2001;9:59–67. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanja N, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, Kumanyika SK. Steps to soulful living (steps): A weight loss program for African-American women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12:363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BM, Paeratakul S, Champagne CM, Ryan DH, Harsha DW, McGee B, Bogle ML. A pilot church-based weight loss program for African-American adults using church members as health educators: A comparison of individual and group intervention. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15:373–378. Retrieved from http://www.ishib.org/journal/ethn-15-3-373.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaman JE, Bellack AS, Brown CH, Yang Y. Assessment of motivation to change substance use in dually-diagnosed schizophrenia patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1798–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S. Ethnic minorities and weight control research priorities: Where are we now and where do we need to be? Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S, Grier S. Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. Future of Children. 2006;16:187–207. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S, Wilson JF, Guilford-Davenport M. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of black women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1993;93:416–422. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)92287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK. Special issues regarding obesity in minority populations. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;119(7, Pt. 2):650–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, Charleston JB. Lose weight and win: A church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among black women. Patient Education and Counseling. 1992;19:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(92)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J, Samuel-Hodge CD. Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforge RG, Velicer WF, Richmond RL, Owen N. Stage distributions for five health behaviors in the United States and Australia. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:61–74. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin MS. How to measure survey reliability and validity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood PA, Yoder JE, Deuster PA. Comparison and cross-validation of cycle ergometry estimates of VO2max. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1997;29:1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199711000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue EE, Jarjoura DG, Sutton KS, Smucker WD, Baughman KR, Capers CF. Longitudinal relationship between elapsed time in the action stages of change and weight loss. Obesity Research. 2004;12:1499–1508. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1992;63:60–66. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabb W, Quinn M, Kerver J, Cook S, Karrison T. The PATH-WAYS church-based weight loss program for urban African-American women at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1518–1523. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, Lux L, Sutton S, Bunton AJ, Lohr KN. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: Summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;139:933–949. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell D, Velicer WF. A decisional balance measure and the stages of change model for weight loss. International Journal of Addiction. 1988;23:729–750. doi: 10.3109/10826088809058836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalon MV, Nich C, Frankforter T, Carroll KM. The URICA as a measure of motivation to change among treatment-seeking individuals with concurrent alcohol and cocaine problems. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2002;16:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. In search of the structure of change. In: Klar Y, Chinsky JM, Fisher JD, Nadler A, editors. Self change: Social psychological and clinical perspectives. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, Fowler JL, Follick MJ, Abrams DB. Attendance and outcome in a work site weight control program: Processes and stages of change as process and predictor variables. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:35–45. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90051-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Rossi SR. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG, Chalela P, Gallion K, Velez LF. Energy balance feasibility study for Latinas in Texas: A qualitative assessment. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, Dilorio C, Blisset D, Rahotep S, Periasamy S. Healthy Body/Healthy Spirit: A church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Education Research. 2002;17:562–573. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebe D, Blissmer B, Greene G, Caldwell M, Ruggiero L, Stillwell KM, Nigg CR. Long-term maintenance of exercise and healthy eating behaviors in overweight adults. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbrocco T, Carter MM, Lewis EL, Vaughn NA, Kalupa KL, King S, Cintron JA. Church-based obesity treatment for African-American women improves adherence. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15:246–255. Retrieved from http://www.ishib.org/journal/ethn-15-2-246.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbrocco T, Hsiao CW, Osborn R. A two-year follow-up weight loss study in African American women; Paper presented at the Society of Behavioral Medicine; Washington, DC. 2007. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Seo DC, Sa J. A meta-analysis of psycho-behavioral obesity interventions among US multiethnic and minority adults. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris AM, Trapp MC, DiClemente CC, Cousins J. Application of the transtheoretical model of behavior change for obesity in Mexican American women. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:655–668. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WC, Poston WCC, Jones L, Kraft MK. Environmental justice: Obesity, physical activity, and healthy eating. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3(Suppl. 1):S30–S54. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallis M, Ruggiero L, Greene G, Jones H, Zinman B, Rossi S, Prochaska JO. Stages of change for healthy eating in diabetes: Relation to demographic, eating-related, health care utilization, and psychosocial factors. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1468–1474. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Lipschutz PE, Williams NN. Comparison of psychosocial status in treatment-seeking women with Class III vs. Class I–II obesity. Obesity. 2006;14(Suppl. 2):90S–98S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott-McQuigg JA, Prochaska TR. Factors influencing participation of African American elders in exercise behavior. Public Health Nursing. 2001;18:194–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16:2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DS, Prewitt TE, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Corrigendum: Weight loss of Black, White and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Obesity. 2009;17:2119–2120. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Anglin K. Effectiveness of a behavioral weight control program for blacks and whites with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:409–413. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. What are the health consequences of being overweight? Washington, DC: Author; 2006. Nov 16, [Google Scholar]