Abstract

Purpose.

Previously, we demonstrated reduced Schlemm's canal cross-sectional area (SC-CSA) with increased perfusion pressure in a cadaveric flow model. The purpose of the present study was to determine the effect of acute IOP elevation on SC-CSA in living human eyes.

Methods.

The temporal limbus of 27 eyes of 14 healthy subjects (10 male, 4 female, age 36 ± 13 years) was imaged by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography at baseline and with IOP elevation (ophthalmodynamometer set at 30-g force). Intraocular pressure was measured at baseline and with IOP elevation by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Vascular landmarks were used to identify corresponding locations in baseline and IOP elevation scan volumes. Schlemm's canal CSA at five locations within a 1-mm length of SC was measured in ImageJ as described previously. A linear mixed-effects model quantified the effect of IOP elevation on SC-CSA.

Results.

The mean IOP increase was 189%, and the mean SC-CSA decrease was 32% (P < 0.001). The estimate (95% confidence interval) for SC-CSA response to IOP change was −66.6 (−80.6 to −52.7) μm2/mm Hg.

Conclusions.

Acute IOP elevation significantly reduces SC-CSA in healthy eyes. Acute dynamic response to IOP elevation may be a useful future characterization of ocular health in the management of glaucoma.

Keywords: ophthalmodynamometer, optical coherence tomography, outflow tract imaging

Visualization of a stress strain response in the aqueous humor outflow tract is presented. Using an ophthalmodynamometer to create an acute IOP increase in normal healthy eyes, morphometric changes in Schlemm's canal can be observed and quantified in OCT imagery.

Introduction

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world.1 Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is a major risk factor for the presence and progression of glaucoma.2–7 Intraocular pressure is regulated by balance between the formation and outflow of aqueous humor.8 The primary pathway for aqueous humor outflow is composed of the trabecular meshwork (TM), Schlemm's canal (SC), and aqueous vasculature (veins and collector channels) leading to scleral veins.9 Previous studies have found a correlation between IOP and SC cross-sectional area (SC-CSA).10

The location of greatest resistance to outflow is the juxtacanicular tissue and the inner wall of SC, the interface between SC and the TM.11,12 Schlemm's canal CSA is reduced when elevated IOP alters TM configuration, pushing it into SC in cadaveric human and animal eyes.13–15 Mechanical stress of the TM and juxtacanicular tissue alters its resistance to outflow, creating a clinical need for the characterization of TM deformation (strain) in response to changes in IOP.15,16

We have recently demonstrated the ability to noninvasively image the primary aqueous humor outflow system in living human eyes distal to and including SC using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT).17–19 Using this technique, we have observed reduced SC-CSA in a human cadaveric outflow model with increased perfusion pressure. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that reduced SC-CSA will be observed during acute IOP elevation using SD-OCT within living normal healthy human eyes.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh approved the study. All subjects gave written informed consent before participation.

Study Protocol

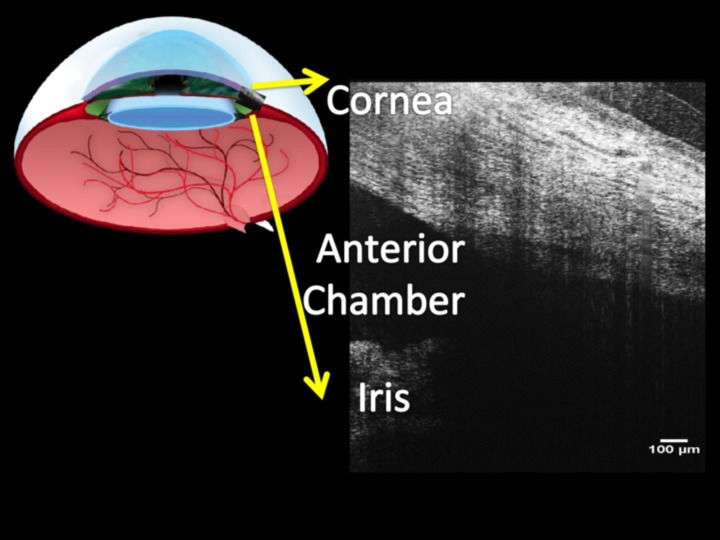

The temporal limbus of 27 eyes of 14 healthy subjects (10 male; 4 female; age 36 ± 13 years, range, 23–63 years) was scanned twice by SD-OCT (Fig. 1). Due to the size and position of the device head rest, imaging of the nasal quadrant with application of an ophthalmodynamometer (ODM, Bailliart Ophthalmodynamometer; Surgical Instruments Co.) was impossible, as the body of the scanner did not allow sufficient space for the ODM to be positioned on the eye. Further, being limited to horizontal raster scans, radial scans of the inferior and superior limbus were also impossible. Two volumetric raster scans were obtained (anterior segment 512 × 128 scan pattern [Cirrus HD-OCT 4000; Zeiss, Inc., Dublin, CA]). The scan protocol was composed of 512 × 128 axial scans (A-scans) distributed over a 4- × 4-mm transverse area. The axial scan resolution was ∼5 μm, with a transverse resolution of 15 μm. The image in Figure 2 comprises 512 adjacent vertical A-scans (each vertical line of pixels within the image is an A-scan), forming a single frame or B-scan. At a rate of 27,000 A-scans per second, the total scan time was ∼2.4 seconds. Chin and forehead rests were used to center the eye in the image frame, and verbal commands were used to direct the volunteer to move the eye to center the desired limbus region in the field of view. This produced SD-OCT scans with the limbus oriented orthogonally to the laser beam. Scanning speed of the device was 27,000 A-scans per second. One hundred twenty-eight B-scans of the limbus were evenly distributed over 4 mm, with adjacent scans separated by 31.25 μm. Scan time was 2 seconds.

Figure 1.

Radial optical coherence tomography images of the limbus (upper left) include a portion of the anterior chamber and iris (lower right), as well as the peripheral cornea and sclera.

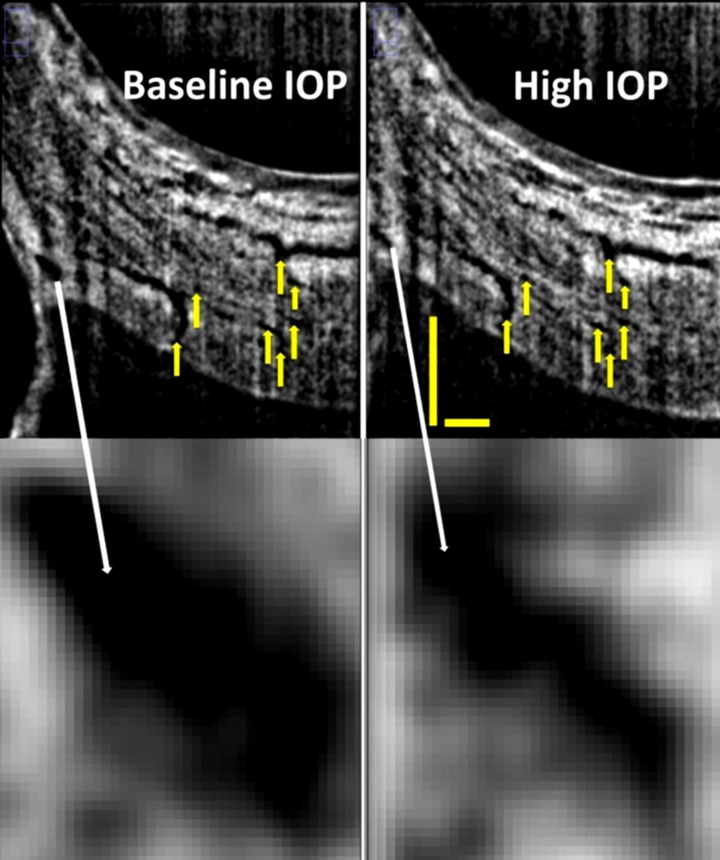

Figure 2.

B-scans of Schlemm's canal (top) at baseline (top left) and during acute IOP elevation (top right) matched based upon vascular landmarks (yellow arrows). Magnification reveals a decrease in Schlemm's canal cross-sectional area from baseline (bottom left) to high IOP (bottom right). Scale bars: 500 μm (scans have an anisotropic aspect ratio, and for that reason the horizontal and vertical scale bars are of different lengths).

The first scan served as a baseline, and the second scan was obtained during application of scleral compression by ODM. After numbing of the eyes with 0.5% proparacaine, the ODM was applied on the temporal sclera with a constant weight of 30 g. The IOP increase specific to each eye produced by application of the ODM was determined by Goldmann applanation tonometry no sooner than 15 minutes after imaging.

Vascular structures were used as landmarks to identify and repeatedly measure the same location before and during IOP elevation (Fig. 2, top, yellow arrows). Specifically, because it was anticipated that IOP would alter the appearance of SC, branch points in the aqueous veins and collector channels distal to SC were identified in baseline and high IOP scans. After confirmation of approximately identical locations before and during IOP elevation, SC-CSA was measured in identical locations at baseline and high IOP scans. Manual segmentation was performed as described previously,19 using a subjective full-width half-height approach.20,21

Image Processing

An automatic routine was used, in which images were thrice averaged with a three-dimensional 3 × 3 × 3 kernel and then processed by local contrast enhancement using adaptive histogram filtering in Fiji (ImageJ 1.45q; National Institutes of Health, http://www.imagej.nih.gov.ij [in the public domain]). A subjective manual adjustment of contrast and brightness was made and applied to the entire image stack. B-scans were excluded if SC's borders were not visible or excessive noise or shadowing was present. When ostia were present, the location of the surrounding wall was extrapolated across the collector channel to provide a border for SC-CSA estimation. Schlemm's canal CSA was measured in five frames separated by 250 μm center to center, evenly spread throughout a 1-mm volume of the 4-mm scan, and centered on the “landmark” frame (Fig. 2), which contained multiple branch points that could be identified in both baseline and high IOP scans. The average of the five measurements was used for analysis.

Statistics

Data on cadaver eyes suggest that an IOP increase of 20 mm Hg would induce a 50% decrease in SC-CSA.15 The authors anticipate a moderate increase in IOP with application of the ODM. Assuming an increase of 5 mm Hg from baseline, the anticipated decrease in SC-CSA would be 12.5%. Further assuming a measurement variability of ∼13%,19 an n of 14 will allow changes as small as 11.25% at 90% power to be detected as statistically significant.

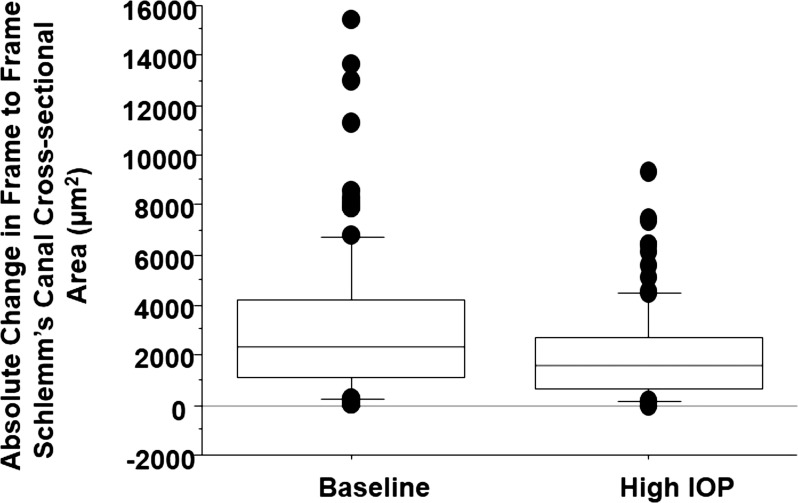

The distribution of SC-CSAs observed at baseline, and absolute differences between adjacent measurement locations and at elevated IOP, were displayed in a box plot. The SC-CSA response to IOP elevation was quantified by linear mixed-effects modeling using the R statistical programming language (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org [in the public domain]). Unlike a linear regression analysis, which attempts to force all subject data to a single relationship represented by the regression line, a linear mixed-effects model takes both the group (the regression line) and the individual responses into account when estimating the systemic and individual variance components.

Results

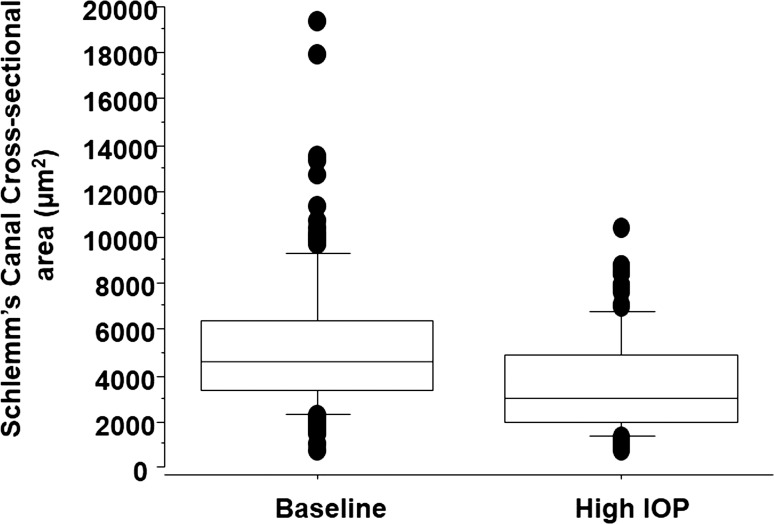

All subjects completed all measurements with no adverse effects or complaints of discomfort. Intraocular pressures and SC-CSAs at baseline and with ODM application are presented in the Table. Applying the ODM significantly increased IOP from 12.5 to 36.1 mm Hg, a 189% increase (P < 0.001). Subjectively, SC compression could be observed as movement of the inner toward the outer, but in a nonuniform manner (Fig. 2, bottom). Schlemm's canal CSA was reduced by 32% (5379.6–3654.9 μm2, P < 0.001) along with frame-to-frame variation in SC-CSA that was reduced at elevated IOP (Figs. 3, 4).

Table.

IOP and Schlemm's Canal Cross-Sectional Area at Baseline and Elevated Pressure, Mean (Standard Deviation)

|

Condition |

OD |

OS |

OU |

|||

|

IOP, mm Hg |

SC-CSA, μm2 |

IOP, mm Hg |

SC-CSA, μm2 |

IOP, mm Hg |

SC-CSA, μm2 |

|

| Baseline | 11.9 (3.0) | 5919.0 (2533.7) | 13.1 (1.2) | 4840.3 (1793.4) | 12.5 (2.3) | 5379.6 (2181.9) |

| IOP elevation | 33.6 (4.9) | 4025.6 (1658.2) | 38.7 (6.2) | 3284.3 (1115.3) | 36.1 (6.0) | 3654.9 (1411.1) |

OD, oculus dexter (Latin: eye right); OS, oculus sinister (Latin: eye left); OU, oculus uterque (Latin: eye both).

Figure 3.

Box plot showing the distribution of SC-CSAs at baseline and during acute IOP elevation.

Figure 4.

Box plot showing the distribution of scan-to-scan SC-CSA difference at baseline and during acute IOP elevation.

The linear mixed-effects model estimated (95% confidence interval) a statistically significant SC-CSA response to IOP change as −66.6 (−80.6 to −52.7) μm2/mm Hg.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that SC-CSA changed by −66.6 μm2/mm Hg in a cohort of normal healthy eyes. This relationship was readily visible as compression of SC, possibly due to movement of the inner wall of SC, in radial SD-OCT sections oriented orthogonal to SC (Fig. 2). The effect of SC compression across the range of areas was visualized in a decrease in the distribution of the SC-CSAs (Fig. 3).

Since the balance between aqueous humor production and uptake regulates pressure, the present findings represent an important step in utilizing aqueous outflow structure morphology to understand the underlying pathologies that lead to an imbalance. Specifically, these data support the hypothesis that morphology and pressure levels in the eye are linked. In the present study, a consistent and predictable morphometric response to acute IOP elevation was documented. While the present cause-and-effect relationship was IOP perturbation leading to morphometric response, the same relationship has been observed with a morphometric perturbation leading to IOP response. Gulati et al.22 implanted a scaffold in SC, inducing a large increase in SC-CSA.22 This morphometric alteration resulted in a decrease in IOP. The same concept may be applied to monitor the effects of minimally invasive nonpenetrating glaucoma procedures and implantation of devices designed to bypass the trabecular network.23–30

Cadaveric models suggested that TM expansion into SC would be observed with IOP elevation.15 Mathematical modeling of the outflow system also predicts compression of SC in response to IOP elevation.31 Assuming that accurate measurements of both SC-CSA and TM thickness response to IOP elevation are feasible in images produced by the clinical device, the foundation laid by Johnson and Kamm's31 modeling may be used to calculate TM stiffness in the human eye in the future. If this speculation proves to be true, it is possible that the technology required for direct measurement of TM stiffness is already in place in many clinics throughout the world. Beyond being useful for the basic understanding of the condition or status of each individual patient's outflow system, TM stiffness is of interest as it has recently been shown to be associated with outflow facility and resistance to outflow.16 Stiffer TMs may be better able to remain stable through fluctuations in IOP.16

There were several limitations in the study. Of the 14 subjects included in the study, only four were older than 45 years of age (48, 49, 53, and 63). Glaucoma is a disease most prevalent in aged eyes, and those eyes are susceptible to elevated IOP.32,33 Further study in an older healthy cohort may increase understanding of the outflow system's response to acute changes in IOP in eyes of ages more frequently associated with glaucoma.

There were several limitations associated with the use of a clinically available device. It is possible that the smallest portions of SC structures are beyond the ability to visualize with the commercially available SD-OCT resolution. If this was the case, then the outline of SC did not include smaller portions extending beyond the identified boundary, and SC size is therefore underestimated in this study. However, it has been demonstrated that image resolution and visualization of small structures is improved by oversampling and averaging, as employed in the present study.34,35 Schlemm's canal CSA measurements obtained by SD-OCT are in good agreement with previously published SC-CSA measurements obtained from histological sections.19 While it is possible that some underestimation of true SC-CSA was present in this study, this does not invalidate the statistically significant difference in SC-SCA that was observed, suggesting that despite the physical limitations of the present generation of hardware, SD-OCT is capable of detecting changes in SC morphology associated with acutely changing IOP, which is an important step in the application of outflow morphometric imaging in the clinical management of glaucoma. Limitations associated with the head rest limited the study to analysis of the temporal quadrant. Imaging of the nasal quadrant with application of the ODM was impossible due to insufficient space for the ODM in front of the eye. The limitation of horizontal raster scans excluded examination of the inferior and superior limbus. Future studies may be more readily accomplished on other imaging platforms that feature smaller scan heads or allow rotation of the scan, facilitating 360° radial scan examination of the entire limbus.

In conclusion, acute IOP elevation significantly reduces SC-CSA in healthy eyes. Acute dynamic response to IOP elevation may be a useful future characterization of ocular health in the management of glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Laura Kagemann, graphic artist, for the original artwork for Figure 1.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health Contracts R01-EY13178 and P30-EY08098, the National Glaucoma Research Program of the American Health Assistance Foundation, the Eye and Ear Foundation (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), and unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, New York).

Disclosure: L. Kagemann, None; B. Wang, None; G. Wollstein, Allergan (C); H. Ishikawa, None; J.E. Nevins, None; Z. Nadler, None; I.A. Sigal, None; R.A. Bilonick, None; J.S. Schuman, P

References

- 1. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90: 262–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Relationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991; 109: 1090–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in east Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325: 1412–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY, Hyman L, Schachat AP. Distribution of intraocular pressure. The Barbados Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997; 115: 1051–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Honkanen R, Nemesure B. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115: 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitchell P, Lee AJ, Rochtchina E, Wang JJ. Open-angle glaucoma and systemic hypertension: the blue mountains eye study. J Glaucoma. 2004; 13: 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Healey PR. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103: 1661–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabelt B, Kaufman P. Aqueuous humor dynamics. In: Kaufman P. ed Adler's Physiology of the Eye. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003: 237–289 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamm ER. The trabecular meshwork outflow pathways: structural and functional aspects. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 648–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong J, Xu J, Wei A, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic assessment of Schlemm's canal in Chinese subjects with primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120: 709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grant WM. Experimental aqueous perfusion in enucleated human eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963; 69: 783–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jocson VL, Sears ML. Experimental aqueous perfusion in enucleated human eyes. Results after obstruction of Schlemm's canal. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971; 86: 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li P, Reif R, Zhi Z, et al. Phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography characterization of pulse-induced trabecular meshwork displacement in ex vivo nonhuman primate eyes. J Biomed Optics. 2012; 17: 076026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Battista SA, Lu Z, Hofmann S, Freddo T, Overby DR, Gong H. Reduction of the available area for aqueous humor outflow and increase in meshwork herniations into collector channels following acute IOP elevation in bovine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 5346–5352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnstone MA, Grant WG. Pressure-dependent changes in structures of the aqueous outflow system of human and monkey eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973; 75: 365–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Camras LJ, Stamer WD, Epstein D, Gonzalez P, Yuan F. Differential effects of trabecular meshwork stiffness on outflow facility in normal human and porcine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 5242–5250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis AW, Kagemann L, Wollstein G, et al. Morphometric analysis of aqueous humor outflow structures with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 5198–5207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kagemann L, Wollstein G, Ishikawa H, et al. 3D visualization of aqueous humor outflow structures in-situ in humans. Exp Eye Res. 2011; 93: 308–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kagemann L, Wollstein G, Ishikawa H, et al. Identification and assessment of Schlemm's canal by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 4054–4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arend O, Remky A, Plange N, Martin BJ, Harris A. Capillary density and retinal diameter measurements and their impact on altered retinal circulation in glaucoma: a digital fluorescein angiographic study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86: 429–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delori FC, Fitch KA, Feke GT, Deupree DM, Weiter JJ. Evaluation of micrometric and microdensitometric methods for measuring the width of retinal vessel images on fundus photographs. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988; 226: 393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gulati V, Fan S, Hays CL, Samuelson TW. Ahmed II, Toris CB. A novel 8-mm Schlemm's canal scaffold reduces outflow resistance in a human anterior segment perfusion model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 1698–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palmiero PM, Aktas Z, Lee O, Tello C, Sbeity Z. Bilateral Descemet membrane detachment after canaloplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010; 36: 508–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matthaei M, Steinberg J, Wiermann A, Richard G, Klemm M. Canaloplasty: a new alternative in non-penetrating glaucoma surgery [in German]. Ophthalmologe. 2011; 108: 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freiberg FJ. Parente Salgado J, Grehn F, Klink T. Intracorneal hematoma after canaloplasty and clear cornea phacoemulsification: surgical management. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012; 22: 823–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klink T, Panidou E, Kanzow-Terai B, Klink J, Schlunck G, Grehn FJ. Are there filtering blebs after canaloplasty? J Glaucoma. 2012; 21: 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mastropasqua L, Agnifili L, Salvetat ML, et al. In vivo analysis of conjunctiva in canaloplasty for glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012; 96: 634–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herdener S, Pache M. Excimer laser trabeculotomy: minimally invasive glaucoma surgery [in German]. Ophthalmologe. 2007; 104: 730–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garcia JP Jr, de la Cruz J, Rosen RB, Buxton DF. Imaging implanted keratoprostheses with anterior-segment optical coherence tomography and ultrasound biomicroscopy. Cornea. 2008; 27: 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Melamed S, Ben Simon GJ, Goldenfeld M, Efficacy Simon G. and safety of gold micro shunt implantation to the supraciliary space in patients with glaucoma: a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009; 127: 264–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson MC, Kamm RD. The role of Schlemm's canal in aqueous outflow from the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983; 24: 320–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Medical backgrounders: glaucoma. Drugs Today (Barc). 2002; 38: 563–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chauhan BC, Mikelberg FS, Balaszi AG, LeBlanc RP, Lesk MR, Trope GE. Canadian Glaucoma Study: 2. risk factors for the progression of open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126: 1030–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hammer D, Ferguson RD, Iftimia N, et al. Advanced scanning methods with tracking optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2005; 13: 7937–7947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meitav N, Ribak EN. Improving retinal resolution by multiple oversampling. Paper presented at: Signal Recovery and Synthesis - Joint AO/SRS Session II: Wavefront Estimation and Image Analysis; July 10–14, 2011; Toronto, Canada http://www.opticsinfobase.org/abstract.cfm?URI=SRS-2011-JTuC2. Accessed March 13, 2014. [Google Scholar]