Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine whether anti-peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 (PAD4) antibodies were present in first-degree relatives of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in two indigenous North American populations with high prevalence of RA.

Methods

Participants were recruited from two indigenous populations in Canada and the United States, including RA patients (probands), their unaffected first-degree relatives, and healthy unrelated controls. Sera were tested for the presence of anti-PAD4 antibodies, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies, and rheumatoid factor (RF). HLA-DRB1 subtyping was performed and participants were classified according to number of shared epitope alleles present.

Results

Antibodies to PAD4 were detected in 24 of 82 (29.3%) probands; 2 of 147 (1.4%) relatives; and no controls (p <0.0001). Anti-CCP was present in 39/144 (27.1%) of the relatives, and there was no overlap between positivity for anti-CCP and PAD4 in the relatives. In RA patients, anti-PAD4 antibodies were associated with disease duration (p=0.0082) and anti-CCP antibodies (p=0.008), but not smoking or shared epitope alleles.

Conclusion

Despite a significant prevalence of anti-CCP in first-degree relatives, anti-PAD4 antibodies were almost exclusively found in established RA. The prevalence of anti-PAD4 antibodies in RA is similar to the prevalence described in other populations and these autoantibodies are associated with disease duration and anti-CCP in RA.

Key Indexing Terms (MeSH): Arthritis, Rheumatoid, Autoantibodies, peptidylarginine deiminase

INTRODUCTION

Autoantibodies directed against citrullinated proteins are highly specific for rheumatoid arthritis (RA).(1) Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) have been shown in multiple studies to be present prior to the onset of RA, with broadening of the autoantibody response as disease onset approaches.(2–7) The family of enzymes known as peptidyl arginine deiminases (PAD) catalyze the citrullination of proteins, and polymorphisms in the gene encoding PAD4 have been associated with RA in some populations.(8–10) Several studies have described the presence of autoantibodies directed against peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 (PAD4) in a subset of patients with RA.(11–14) In established RA, anti-PAD4 antibodies have been associated with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies and more severe disease.(11–13)

First degree relatives of people with RA have a 3-fold or higher risk of developing RA compared to individuals without a family history, and this risk is further increased in multiplex families.(15) Indigenous North American populations have high rates of RA, with evidence of familial clustering of disease.(16–19) Because multiple studies have documented the presence of pre-clinical RA-related autoantibodies years prior to the onset of RA and high rates of RA in indigenous North American populations, we enrolled unaffected first-degree relatives from these populations in a study focused on early identification of RA. In previous studies, we have shown a high prevalence of anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor (RF) in first degree relatives without clinical RA in the Cree/Ojibway population of Central Canada.(20)

Anti-PAD4 antibodies have also been detected prior to the clinical diagnosis of RA in a small subset of patients. In a study by Kolfenbach et al.,(21) 18% of people who developed RA had PAD4 antibodies present in pre-clinical serum, with a mean duration of positivity prior to diagnosis of 4.7 years. In the majority of patients, anti-PAD4 antibodies were detected after the development of anti-CCP antibodies. We hypothesized that anti-PAD4 antibodies might be present in a subset of first degree relatives, especially those with anti-CCP antibodies. In this study we tested for anti-PAD4 antibodies in indigenous North American people with RA, their first degree relatives without RA, and in healthy controls and found that despite the high prevalence of anti-CCP in the first-degree relatives, anti-PAD4 antibodies were almost exclusively found in people with established RA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment of study participants

Participants were recruited from two indigenous North American populations in Canada and the United States. This included both urban and rural locations in Manitoba and Alaska. The study population in Manitoba has been previously described,(22, 23) and in Alaska, participants were recruited in the largest city (Anchorage), as well as in two communities in Southeast Alaska. We invited the following three groups to participate: 1) RA patients (probands); 2) their unaffected first-degree relatives (FDRs); and 3) healthy controls without a personal or family history of RA or other autoimmune disease. All probands met the 1987 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for RA.(24) The probands and FDRs were all First Nations or Alaska Native people, while we included both indigenous and Caucasian controls. All study participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba, the Alaska Area Institutional Review Board, the Band Councils of the individual study communities in Manitoba, and the tribal health organizations of the study communities in Alaska.

Study visit and clinical data

Participants completed a detailed questionnaire including demographics, environmental exposures, joint symptoms, and family history of autoimmune diseases. After completing the questionnaire, all participants underwent a joint examination by a rheumatologist to determine whether inflammatory arthritis was present, including a 66/68 swollen/tender joint count. At the study visit, whole blood was drawn and serum was obtained by centrifugation, following standard operating procedures. Sera and whole blood were stored at −80°C until testing.

Cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody testing

Sera were tested for the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies using a commercially available anti-CCP2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; INOVA Diagnostics, San Diego, CA, USA). As previously described,(22) a cutoff of ≥40 units was used to maximize specificity. In addition, all first degree relative sera with positive CCP antibodies were re-tested for confirmation of positivity.

Rheumatoid factor testing

IgM rheumatoid factor was tested by an ELISA calibrated with a standard of known IU measured by nephelometry. As previously described,(22) because cutoff levels have not been established in this population and the smoking prevalence is high, the cutoff for a positive RF was set at ≥ 50 IU, based on a level where 95% of Caucasian controls were seronegative.

Anti-PAD4 antibody testing

Anti-PAD4 antibodies were detected in serum by immunoprecipitation as previously described.(11, 21) Antibody testing was performed at the Johns Hopkins University Rheumatic Disease Research Core Center (RDRCC). Briefly, 35S-methionine (Perkin Elmer) labeled PAD4 was generated by in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT) of the full-length human cDNA cloned from HL-60 cells (NCBI accession number NP 036519.1) using a commercially available kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). 1ul of IVTT product was mixed with 1ul of serum and incubated \ for 1 hour at 4°C in NP-40 lysis buffer containing 0.2% BSA and protease inhibitors. Protein A beads (Thermo Scientific) were added and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. The beads were washed by resuspension and pelleting in NP-40 lysis buffer and then boiled in SDS sample buffer. Samples were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoprecipitated proteins were visualized by radiography. Densitometry was performed, values were normalized to a known high titer anti-PAD4 positive serum, and antibody positivity was defined as a normalized densitometry value of >0.01. A semi-quantitative scale (0, 1, 2, and 3+) based on densitometry of scanned immunoprecipitation autoradiographs was used to assign a value to each serum sample, as previously described.(11, 21)

HLA testing

HLA-DRB1 typing was performed by polymerase chain reaction using sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers and sequence-based typing. Study participants were classified according to the presence or absence of shared epitope alleles. The following alleles were included as shared epitope alleles: DRB1*0101, 0102, 0401, 0404, 0405, 0408, 0410, 1001, and 1402, as previously described.(22, 23)

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed using t-tests, ANOVA, or nonparametric alternative tests as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed with Chi square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed using STATA/IC version 11.2 (STATA LP, College Station, TX) and GraphPad Prism version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study population by group are shown in Table 1. The first-degree relatives and controls were similar with respect to age, sex distribution, and prevalence of smoking, and were younger than the RA probands. Smoking prevalence was high in all study groups. Shared epitope prevalence and number of copies were tested in the RA probands and first-degree relatives, but not in the controls. For the probands, the mean RA disease duration at the time of the study visit was 10.9 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Rheumatoid arthritis probands (n=82) | First-degree relatives (n = 147) | Indigenous North American controls (n =44) | Caucasian controls (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age at study visit, years, mean (SD) | 53.4 (14.3) | 39.3 (13.0) | 37.6 (11.7) | 38.8 (10.6) |

|

| ||||

| RA disease duration at study visit, years, mean (SD) | 14.2 (10.9) | |||

|

| ||||

| Sex, n (%) female | 71 (86.6) | 99 (67.3) | 31 (70.4) | 13 (65.0) |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Ever, n (%) | 57 (69.5) | 105 (71.4) | 26 (59.1) | 14 (70) |

| Current, n (%) | 31 (39.2) | 67 (47.5) | 15 (34.1) | 9 (45) |

|

| ||||

| Shared epitope | ||||

| Any copy, n (%) | 60/65 (92.3) | 88/103 (85.4) | NA | NA |

| 2 copies, n (%) | 30/65 (46.2) | 28/103 (27.2) | ||

INA: indigenous North American; SD: standard deviation; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; NA: not available

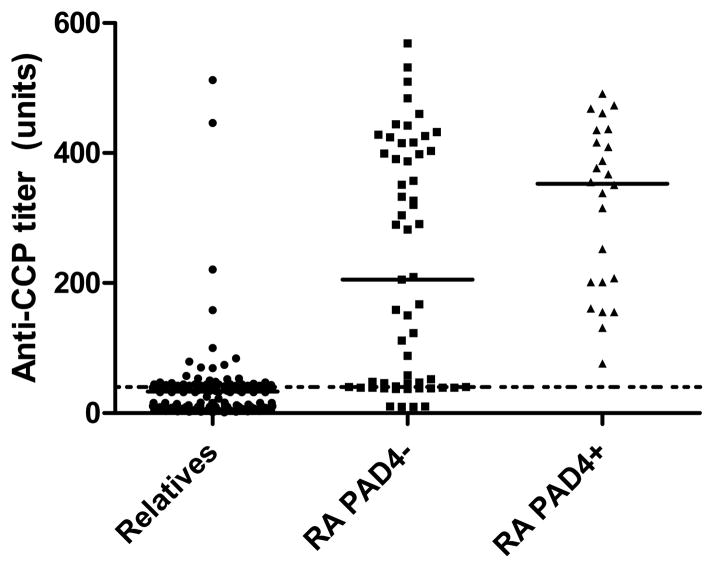

The prevalence of autoantibodies in the RA probands and the first-degree relatives are shown in Table 2. All controls were negative for anti-CCP, RF, and anti-PAD4 (data not shown). All autoantibodies were more common in probands than in relatives (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). Anti-PAD4 antibodies were present in 24 of 82 probands (29.3%) and in only 2 of 147 relatives (1.4%), despite a high prevalence of anti-CCP antibodies in the relatives (27.1%). As shown in Figure 1, the median titer of anti-CCP antibodies was lowest in the relatives, intermediate in the RA probands who were anti-PAD4 negative, and highest in the probands who were anti-PAD4 positive (33, 205, and 353 units, respectively, p<0.0001). Anti-PAD4 and anti-CCP positivity overlapped in all 24 probands with anti-PAD4, and the overlap between anti-PAD4 and RF was slightly less frequent (22 of 24 probands). None of the relatives with anti-PAD4 antibodies had anti-CCP antibodies present, and only one of the two had RF detected. None of the relatives had inflammatory arthritis at the time of the study visit, and neither of the relatives with anti-PAD4 antibodies present have had a follow-up visit to determine whether they have developed joint symptoms since the visit. Serial serum specimens were not available for these two relatives to evaluate for the persistence of anti-PAD4 antibodies over time. Anti-PAD4 antibody densitometry values were assigned as described in the methods section. Both relatives were strongly positive for anti-PAD4 antibodies with had densitometry readings of 3+.

Table 2.

Autoantibody Results

| Autoantibody | Rheumatoid arthritis probands (n=82) | First-degree relatives (n = 147) |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-PAD4 positive, n (%) | 24 (29.3) | 2 (1.4) |

| CCP2 positive (≥40 AU), n (%) | 68/81 (84.0) | 39/144 (27.1) |

| RF positive (≥50 IU), n (%) | 64/74 (86.5) | 24/126 (19.1) |

| CCP and RF positive, n (%) | 59/73 (80.8) | 9/123 (7.3) |

| Anti-PAD4 and CCP positive, n (%) | 24/81 (29.6) | 0/144 (0) |

| Anti-PAD4 and RF positive, n (%) | 22/74 (29.7) | 1/126 (0.8) |

p < 0.0001 for all comparisons of prevalence in probands vs. relatives.

All controls were negative for anti-PAD4, CCP, and RF

Figure 1. Anti-CCP antibody titers by group.

Anti-CCP titers in units by group (relatives, probands without anti-PAD4 antibodies present (RA PAD4−), and probands with anti-PAD4 antibodies present (RA PAD4+). Median titer noted on plot for each group, and dotted line at cutoff for positive anti-CCP antibodies (40 units).

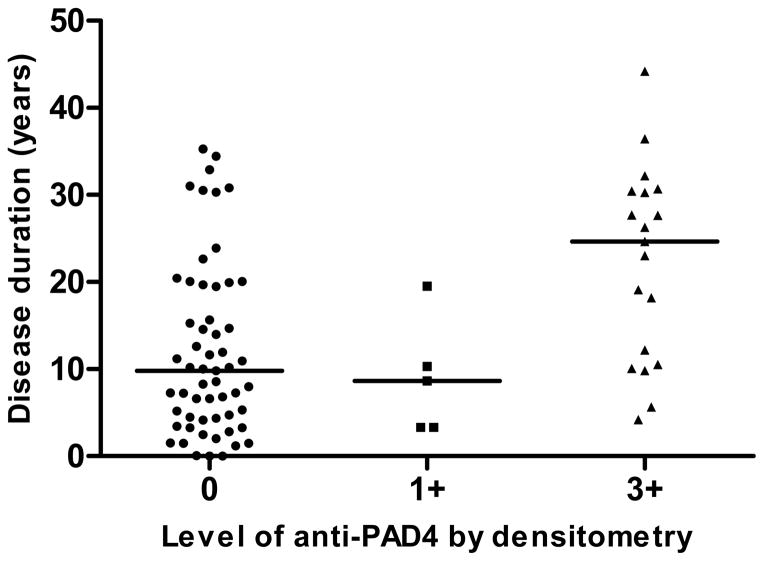

Anti-PAD4 associations were evaluated in the RA probands, as shown in Table 3. RA probands with anti-PAD4 antibodies had significantly longer disease duration than those without PAD4 antibodies (p=0.0082) and were more commonly anti-CCP antibody positive (p=0.008). There was non-statistically significant trend toward lower frequency of smoking (either ever or current) in anti-PAD4 positive probands (p=0.067). There was no association of anti-PAD4 with sex or shared epitope presence, though at least one shared epitope allele was present in a high proportion of the probands (92% overall). Because our study design is primarily focused on the characteristics of the first-degree relatives with possible pre-clinical RA, radiographic data were not available on all probands, and we were not able to assess the association of anti-PAD4 with radiographic damage. Of the 24 probands with anti-PAD4 antibodies, 19 (79.2%) had densitometry values of 3+, while the remaining 5 (20.8%) had densitometry values of 1+. In Figure 2, disease duration of RA probands is plotted against level of anti-PAD4 antibodies. In those with 3+ densitometry readings, disease duration was longest (median 24.6 years, as compared to 9.8 in the group without anti-PAD4 antibodies and 8.6 in those with 1+ densitometry, p=0.0028 for comparison).

Table 3.

Anti-PAD4 Associations in Probands

| Characteristic | Anti-PAD4+ (n=24) | Anti-PAD4− (n=58) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease duration, years, median | 19.3 | 9.8 | 0.0082 |

| Sex, n (%) female | 22 (91.7) | 49 (84.5) | 0.495 |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 13 (54.2) | 44 (75.9) | 0.067 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 5/22 (22.7) | 26/57 (45.6) | 0.157 |

| CCP2 positive (≥40 AU), n (%) | 24 (100) | 44/57 (77.2) | 0.008 |

| RF positive (≥50 IU), n (%) | 22/23 (95.7) | 42/51 (82.4) | 0.158 |

| Any shared epitope allele, n (%) | 20/21 (95.2) | 40/44 (90.9) | 1.000 |

Figure 2. Rheumatoid arthritis disease duration by level of anti-PAD4 by densitometry in probands.

Disease duration in years, with median noted on plot. Densitometry labeled as 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+ as defined in methods. No individuals had densitometry readings of 2+.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we tested for anti-PAD4 antibodies in the sera of RA patients and their first-degree relatives in a population with high rates of RA and anti-CCP positivity. We hypothesized that anti-PAD4 antibodies would be detectable in a significant proportion of first-degree relatives with anti-CCP antibodies but without RA, given the high frequency of anti-CCP antibodies and previous evidence that anti-PAD4 antibodies can precede clinical RA.(21) However, despite the high frequency of anti-CCP antibodies in the first-degree relatives, we found that anti-PAD4 antibodies were almost exclusively found in established RA patients and not in first-degree relatives.

Anti-PAD4 antibodies were found in 29% of RA patients, which is consistent with the prevalence in other published reports (ranging from 23%–50%).(11–14, 21, 25, 26) We examined associations with anti-PAD4 antibodies in RA and found that anti-PAD4 positivity was associated with disease duration and anti-CCP positivity. There was a non-significant trend toward lower prevalence of smoking among RA probands with anti-PAD4 antibodies compared to those without anti-PAD4 antibodies and no association with shared epitope alleles. These findings are consistent with previous reports, which have shown an association of anti-PAD4 with disease duration(11) and anti-CCP antibodies,(11–13) but not smoking(13) or shared epitope.(11, 12)

Based on the findings of this study and Kolfenbach et al,(21) it appears likely that in the majority of cases of RA, anti-CCP antibodies appear in serum prior to the development of anti-PAD4 antibodies. Although much remains to be determined about the timing of anti-PAD4 development in the setting of pre-clinical and very early RA, it appears that antibodies directed against PAD4 develop either just prior to onset of RA (but after anti-CCP antibody development) or after RA onset. Consistent with this finding, only 1.4% of the first degree relatives tested had high titer PAD4 antibodies, while 27.1% had anti-CCP antibodies. Since our study is designed to prospectively evaluate relatives who may or may not develop RA, and the time to potential RA diagnosis is unknown, the percentage of anti-PAD4 positives in this group is likely lower than would be expected in a retrospective evaluation of people who have already developed RA. The finding that the prevalence of anti-PAD4 antibodies increases with duration of RA in this study and others supports the hypothesis than anti-PAD4 development occurs later.(11)

Potential mechanisms of development of autoantibodies against PAD4 and the role of these autoantibodies in disease initiation and propagation have been explored in several studies. PAD4 has been postulated to have a pathogenic role in RA due to its ability to citrullinate antigens, its localization in the synovium in the setting of inflammatory arthritis, and increased synovial expression in the setting of more profound inflammation.(27) It has been hypothesized that PAD4 may generate citrullinated antigens, which leads to the development of an anti-CCP autoantibody response, and subsequent generation of autoantibodies targeting PAD4 due to its close association with its cognate substrate.(21, 28) Consistent with the hypothesis that PAD4 may contribute to disease initiation or propagation in RA, it has recently been shown that anti-PAD3/4 cross-reactive antibodies increase the enzymatic activity of PAD4 by decreasing the enzyme’s calcium requirement.(29) In contrast to the above findings, Auger et al.(30) found that the majority of anti-PAD4 antibodies inhibit citrullination of fibrinogen and hypothesized that anti-PAD4 antibodies precede antibodies against citrullinated proteins in the development of RA. Clearly, additional research is needed to clarify the mechanism of anti-PAD4 antibody formation and the pathogenic role of these autoantibodies in RA.

The role of other PADs in RA also remains to be determined. Recently, human PAD2, PAD3, and PAD4 have all been shown to be expressed in neutrophils and to have different substrate specificities.(31) Furthermore, PAD generated by the oral bacterium, Porphyromonas gingivalis, has been shown to citrullinate human fibrinogen and α-enolase, which could account for the observed association between periodontal disease and RA.(32) In animal models, a pan-PAD inhibitor reduced synovial and serum citrullination, reactivity to citrullinated epitopes, and disease activity in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis, suggesting that PAD is necessary for inflammatory arthritis in this model.(33) PAD inhibition has been proposed as a potential therapeutic option for RA.(34)

This study has a few limitations. First, the focus of our study is healthy first-degree relatives of RA patients who do not yet have RA themselves. Because this is a prospective study, it is not yet known how many of these relatives will go on to develop RA. However, the high proportion of individuals with anti-CCP antibodies present and the high prevalence of RA in these populations makes it likely that a significant proportion will develop RA. Furthermore, we are continuing these longitudinal studies in order to be able to answer that question more definitively in the future, including re-testing anti-PAD4 antibodies in the relatives over time and identifying possible predictors of imminent RA. Second, our focus on the relatives meant that we did not collect longitudinal radiographic data on all probands. Therefore, we were not able to confirm previous findings that anti-PAD4 antibodies are associated with radiographic damage in RA. However, assessing associations of anti-PAD4 in established RA was not our primary focus in this analysis, and several other studies have already confirmed the radiographic associations. We did not include a non-autoimmune chronic inflammation control group in this study. However, given our generally negative results in the relatives, we feel that this is not a significant limitation. Our assay only detected antibodies directed against uncitrullinated PAD4, so we are unable to comment on the prevalence or significance of antibodies directed against citrullinated PAD4. Finally, the high prevalence of HLA shared epitope alleles and smoking in the population likely affected our ability to detect any associations between anti-PAD4 antibodies and these variables, if present.

In summary, we found that the prevalence of anti-PAD4 antibodies in indigenous North American populations with established RA was similar to the prevalence in other populations. Anti-PAD4 antibodies were almost exclusively present in the setting of RA, and were uncommon in first-degree relatives without RA, even among relatives with anti-CCP antibodies present. This suggests that anti-PAD4 antibody development may occur more proximal to the onset of clinical RA than anti-CCP antibody. Further studies are needed to examine the role of anti-PAD4 antibodies in the development and progression of RA.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, the Chiefs and Band Councils of the Norway House and St. Theresa Point communities, and the tribal health organizations in Alaska for their support of this study and David Hines from the RDRCC for technical support with the anti-PAD4 immunoprecipitation assays.

Sources of support:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, grant MOP 7770 (Dr. El-Gabalawy), the National Institute of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AR053503, the Sibley Memorial Hospital grant (Drs. Darrah and Rosen) and NIH grant T32 AR048522 (Dr. Darrah).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Journal of Rheumatology following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version (J Rheum 2013 Sep;40(9):1523-28) is available online at: http://www.jrheum.org/content/40/9/1523.long.

References

- 1.Whiting PF, Smidt N, Sterne JA, Harbord R, Burton A, Burke M, et al. Systematic review: accuracy of anti-citrullinated Peptide antibodies for diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Apr 6;152(7):456–64. W155–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Oct;48(10):2741–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MH, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb;50(2):380–6. doi: 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, de Jong BA, Breedveld FC, Verweij CL, et al. Autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Mar;50(3):709–15. doi: 10.1002/art.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majka DS, Deane KD, Parrish LA, Lazar AA, Baron AE, Walker CW, et al. Duration of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis-related autoantibody positivity increases in subjects with older age at time of disease diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jun;67(6):801–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van de Stadt LA, de Koning MH, van de Stadt RJ, Wolbink G, Dijkmans BA, Hamann D, et al. Development of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Nov;63(11):3226–33. doi: 10.1002/art.30537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokolove J, Bromberg R, Deane KD, Lahey LJ, Derber LA, Chandra PE, et al. Autoantibody epitope spreading in the pre-clinical phase predicts progression to rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki A, Yamada R, Chang X, Tokuhiro S, Sawada T, Suzuki M, et al. Functional haplotypes of PADI4, encoding citrullinating enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase 4, are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2003 Aug;34(4):395–402. doi: 10.1038/ng1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikari K, Kuwahara M, Nakamura T, Momohara S, Hara M, Yamanaka H, et al. Association between PADI4 and rheumatoid arthritis: a replication study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Oct;52(10):3054–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plenge RM, Padyukov L, Remmers EF, Purcell S, Lee AT, Karlson EW, et al. Replication of putative candidate-gene associations with rheumatoid arthritis in >4,000 samples from North America and Sweden: association of susceptibility with PTPN22, CTLA4, and PADI4. Am J Hum Genet. 2005 Dec;77(6):1044–60. doi: 10.1086/498651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris ML, Darrah E, Lam GK, Bartlett SJ, Giles JT, Grant AV, et al. Association of autoimmunity to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 with genotype and disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jul;58(7):1958–67. doi: 10.1002/art.23596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halvorsen EH, Pollmann S, Gilboe IM, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Odegard S, et al. Serum IgG antibodies to peptidylarginine deiminase 4 in rheumatoid arthritis and associations with disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Mar;67(3):414–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J, Zhao Y, He J, Jia R, Li Z. Prevalence and significance of anti-peptidylarginine deiminase 4 antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;35(6):969–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takizawa Y, Sawada T, Suzuki A, Yamada R, Inoue T, Yamamoto K. Peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PADI4) identified as a conformation-dependent autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005 May-Jun;34(3):212–5. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Familial associations of rheumatoid arthritis with autoimmune diseases and related conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Mar;60(3):661–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferucci ED, Templin DW, Lanier AP. Rheumatoid arthritis in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Feb;34(4):662–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnabe C, Elias B, Bartlett J, Roos L, Peschken C. Arthritis in Aboriginal Manitobans: evidence for a high burden of disease. J Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;35(6):1145–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oen K, Robinson DB, Nickerson P, Katz SJ, Cheang M, Peschken CA, et al. Familial seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in north american native families: effects of shared epitope and cytokine genotypes. J Rheumatol. 2005 Jun;32(6):983–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Templin DW, Boyer GS, Lanier AP, Nelson JL, Barrington RA, Hansen JA, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in Tlingit Indians: clinical characterization and HLA associations. J Rheumatol. 1994 Jul;21(7):1238–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioan-Facsinay A, Willemze A, Robinson DB, Peschken CA, Markland J, van der Woude D, et al. Marked differences in fine specificity and isotype usage of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody in health and disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Oct;58(10):3000–8. doi: 10.1002/art.23763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, O’Donnell CI, Gilliland WR, Edison JD, et al. Autoimmunity to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 precedes clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2633–9. doi: 10.1002/art.27570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Gabalawy HS, Robinson DB, Smolik I, Hart D, Elias B, Wong K, et al. Familial clustering of the serum cytokine profile in the relatives of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Jun;64(6):1720–9. doi: 10.1002/art.34449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Gabalawy HS, Robinson DB, Hart D, Elias B, Markland J, Peschken CA, et al. Immunogenetic risks of anti-cyclical citrullinated peptide antibodies in a North American Native population with rheumatoid arthritis and their first-degree relatives. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jun;36(6):1130–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Mar;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halvorsen EH, Haavardsholm EA, Pollmann S, Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK, et al. Serum IgG antibodies to peptidylarginine deiminase 4 predict radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumour necrosis factor-alpha blocking agents. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Feb;68(2):249–52. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Li J. Predominance of IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses of autoantibodies to peptidylarginine deiminase 4 in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Apr;30(4):563–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foulquier C, Sebbag M, Clavel C, Chapuy-Regaud S, Al Badine R, Mechin MC, et al. Peptidyl arginine deiminase type 2 (PAD-2) and PAD-4 but not PAD-1, PAD-3, and PAD-6 are expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovium in close association with tissue inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Nov;56(11):3541–53. doi: 10.1002/art.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenberg P, Roth B, Wollheim FA. Peptidylarginine deiminases and the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: a reflection of the involvement of transglutaminase in coeliac disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2009 Dec;20(8):749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darrah E, Giles JT, Bull H, Andrade F, Rosen A. Anti-Peptidylarginine Deiminase 3/4 Cross-Reactive Antibodies: A Novel Biomarker with Clinical and Mechanistic Implications in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012;64( Suppl 10):S722. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auger I, Martin M, Balandraud N, Roudier J. Rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 inhibit citrullination of fibrinogen. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Jan;62(1):126–31. doi: 10.1002/art.27230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darrah E, Rosen A, Giles JT, Andrade F. Peptidylarginine deiminase 2, 3 and 4 have distinct specificities against cellular substrates: novel insights into autoantigen selection in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan;71(1):92–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.151712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wegner N, Wait R, Sroka A, Eick S, Nguyen KA, Lundberg K, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and alpha-enolase: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2662–72. doi: 10.1002/art.27552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willis VC, Gizinski AM, Banda NK, Causey CP, Knuckley B, Cordova KN, et al. N-alpha-benzoyl-N5-(2-chloro-1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine amide, a protein arginine deiminase inhibitor, reduces the severity of murine collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2011 Apr 1;186(7):4396–404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangat P, Wegner N, Venables PJ, Potempa J. Bacterial and human peptidylarginine deiminases: targets for inhibiting the autoimmune response in rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):209. doi: 10.1186/ar3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]