Abstract

In the 1980s, the combined effects of deinstitutionalization from state mental hospitals and the economic recession increased the number and transformed the demographic profile of people experiencing homelessness in the United States. Specialized health care for the homeless (HCH) services were developed when it became clear that the mainstream health care system could not sufficiently address their health needs. The HCH program has grown consistently during that period; currently, 208 HCH sites are operating, and the program has become embedded in the federal health care system. We reflect on lessons learned from the HCH model and its applicability to the changing landscape of US health care.

In the 1980s, the combined effects of deinstitutionalization from state mental hospitals and the economic recession radically increased the number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States and transformed their demographic profile from primarily men with alcohol problems living in traditional skid rows1 to a diverse population dispersed throughout US communities.2 Although the media focused on mental illness at that time,3 evidence was accumulating on the high rates of acute and chronic physical illness of the new homeless as well as the inability of mainstream sources to address them.4,5 The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trust funded 19 demonstration projects in 1985 to determine whether, and how, communities offering specialized health care for the homeless (HCH) services could improve access and quality of health care for these populations. More than 30 years later, HCH projects have become embedded in the federal health care system, with 208 currently operating nationally and the number increasing each year. In this article, we reflect on lessons learned from the HCH model and its applicability to the changing landscape of US health care.

BACKGROUND

Throughout the 1980s, the number of persons experiencing homelessness surged; much of the blame went to concurrent cuts in housing and social services, the aftereffects of deinstitutionalization, and a deteriorating economy. Gentrification also contributed to a loss of traditional low-cost dwellings by leaving fewer housing options to those on the brink of homelessness and displacing many poor persons, thereby increasing visibility and public awareness of newly homeless persons.6 Concerns about rapidly growing demands on service systems fueled local and national attempts to accurately enumerate homeless persons.7–10 Media attention on effects of deinstitutionalization initially led to substantial interest in determining how many homeless persons had alcohol, drug, or mental health issues,11–16 yet it became clear that prevalence rates on these issues varied dramatically depending from where samples were drawn.17

The focus increasingly shifted to better understanding and categorizing who made up the heterogeneous homeless population18,19 and identifying key subgroup differences.20–22 Among women and families, domestic violence, physical and sexual assault, and intergenerational poverty were highlighted as contributors to homelessness.23 Unattached youths made up a growing proportion of the homeless population,24–27 and increased awareness of foster care histories in unattached youths and homeless adults28–33 brought to the fore the faltering child welfare system as a contributor to homelessness. Individuals using crack cocaine were a concern because crack use was associated with risky behaviors that increased the spread of HIV.34,35 Homeless veterans, many from the Vietnam era, brought attention to the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder and barriers to accessing health and other benefits to which veterans were entitled.36,37

HEALTH SERVICE USE AND BARRIERS TO CARE

The negative impact of homelessness on a person’s physical health is especially well documented. From the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, researchers consistently found disproportionately higher rates of hypertension, respiratory illness, tuberculosis, HIV, infestations, and other diseases among homeless persons compared with the general population.38–44 Although fewer studies with recent data are available, research findings and reports have continued to show disparities in physical health between housed and homeless persons in samples drawn from homeless adults living in shelters,45 jailed inmates,46 individuals reporting HIV-positive status,47 and patients using HCH clinics.48

Poverty and homelessness contribute to ill health by presenting unique barriers to self-care and access to health services as well as heightened exposure to communicable diseases and parasites easily spread in crowded conditions, such as shelters. For example, untreated lice infections and insect bites frequently lead to serious, even life-threatening, systemic infections such as cellulitis among people who are homeless. Lack of permanent housing complicates basic self-care and treatment adherence. For example, inability to store medications makes it difficult to keep pills intact or meet refrigeration requirements. Limits on shelter stays during the daytime and competing needs to seek food and employment also interfere with regular administration of medication as prescribed, as well as scheduled follow-up visits with health care providers. On the whole, “Poverty remains a powerful social determinant of poor health, and persons struggling to survive without stable housing are particularly vulnerable.”49(pxxix)

Most homeless persons lack health insurance. During the 1980s recession, several state governments established income thresholds for Medicaid eligibility well below the poverty level, eliminating Medicaid insurance for many poor individuals on the threshold.50 For many, the emergency department became the best option for acute health care.51 Tangible access barriers to doctors and clinics, such as limited hours, noncentral locations, and intake requirements of identification, insurance, and a permanent address and less obvious barriers, such as disrespectful attitudes, apathetic treatment, and overt prejudices toward impoverished people, all contributed to this substitution of the emergency department for the primary care provider. Hospitalization also underwent changes as a new system based on diagnosis (diagnosis-related groupings) was instituted to reduce inpatient stays for Medicare- or Medicaid-insured disabled and elderly people.52,53 Although diagnosis-related groupings reduced spending among federal insurance programs, many very poor, newly discharged patients arrived at shelters in wheelchairs and holding supplies for dressing changes.

THE HEALTH CARE FOR THE HOMELESS MODEL

In response to the needs for health care treatment among people who were homeless, in 1984, 2 philanthropic foundations, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trust, jointly invited applications from the 50 most populous US cities, including Washington, DC, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, to compete for a 4-year grant to support health care service delivery to homeless people. The funders stipulated that grantees would need to supplement foundation support after 2 years, obtain oversight from a coalition of organizations and stakeholders, and begin formation of a safety net of collaborators. By 1985, HCH grants had been awarded in 19 cities across the United States.

Grantee approaches to service delivery varied markedly. Some co-located in existing community clinics, some transformed vans into well-supplied mobile clinics to provide health care at various locations where homeless people were likely to congregate, and still others erected temporary clinics at homeless drop-in centers and shelters, bringing portable examination tables, medical supplies, and screens for privacy, and dismantling them after each clinic session. The menu of services also differed, provided by various combinations of doctors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants. The grantees shared experiences, strategies, and learning at annual meetings sponsored by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, an organization established to provide HCH staff with training and other types of assistance.54 By June 1986, the 19 HCH grantees had provided care to 30 000 individual clients, including 2000 aged 15 years or younger.55

As urban communities struggled to address the needs of a growing homeless population, momentum to support funding for health care services grew from a variety of sources, including advocates, the media, and the federal government. In a congressional action to address aspects of homelessness, the Health Professions Training Act of 1985 (Pub L No. 99–129) mandated, among other things, that the US Department of Health and Human Services ask the Institute of Medicine to study the delivery of health care services to homeless persons.56 The resulting report, incorporating the evaluation of the 19 HCH projects, added academic and professional credibility to arguments about the diversity of the growing homeless population, the breadth and depth of their health care needs, and the mainstream health system’s inability to address them.57 An array of voices from the media and advocates added to the momentum. In 1986, for example, a new nonprofit charity organization called Comic Relief chose HCH as a primary recipient for proceeds from its annual national telethons spearheaded by well-known entertainers Billy Crystal, Whoopi Goldberg, and Robin Williams.

On July 22, 1987, the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act (Pub L No. 100-77) was passed58 to establish distinct assistance programs for the growing number of homeless persons, representing the first significant federal legislative response to homelessness. Title VI of the McKinney–Vento Act established the HCH program, the only federal program with responsibility for addressing the primary health care needs of homeless people.2 The McKinney–Vento Act also established the first national definition of a homeless individual:

(1) An individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence; [or] (2) an individual who has a primary nighttime residence that is- (A) a supervised or publicly operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (including welfare hotels, congregate shelters, and transitional housing for the mentally ill); (B) an institution that provides a temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized; or (C) a public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings.59(subsection 103)

Growth of Health Care for the Homeless

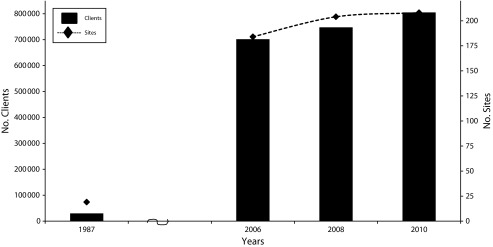

The HCH program has grown significantly since its origin and become embedded in the federal health care system. It is currently administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration. In 1996, the Health Consolidation Act placed HCH sites under the umbrella of community health centers and allowed them to receive federally qualified health center status, which in turn enabled clinics to obtain supplemental funding for every medical encounter or visit made by Medicaid-insured clients.58 In 2010, 208 funded HCH sites served 805 064 clients (Figure 1).55,60,61 These sites included 10 HCH sites targeting children and youths that had originally been funded using the definition of homeless children and youths as

children living in precarious housing situations, e.g., in a family which is in unstable or inadequate housing … [and children] … such as those in the foster care system, children living with relatives or other adults who are not their parents, and unattached adolescents.62(subsection 340)

FIGURE 1—

Total clients and number of sites: Health Care for the Homeless, United States, 1987, 2006, 2008, and 2010.

Source. Wright et al. 198755; Health Resources and Services Administration 2012.60,61

Key Strategies and Innovations

The Health Resources and Services Administration HCH program was modeled after the original 19 demonstration projects envisioned and funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Pew Charitable Trust to provide a specialized source of health care to circumvent the access barriers experienced by people who are homeless. The HCH model emphasized the multidisciplinary approach to care and coordination of efforts with other community health providers and social service agencies. Although these features were mandated for the original grantees, they—and the sites funded hence—actualized, refined, and formalized them to uniquely meet the complex needs of the diverse populations they have served.

Outreach and engagement.

HCH projects faced unique barriers in making health care accessible to their target population of people experiencing homelessness: those in greatest need often had deep (and well-earned) mistrust of established institutions such as clinics or hospitals and were uninterested in speaking with anyone connected to those institutions, and many lived nomadically or in hard-to-find locations. Sophisticated mobile clinics, and co-locating and improvising temporary clinics in homeless drop-ins and shelters, alleviated critical access barriers and enabled health care providers to build trust and engage with many underserved persons. Yet for the significant minority of those who remained elusive, HCH projects engaged outreach workers and embedded outreach as an integral element in their services and approach.

Outreach workers were responsible for locating homeless individuals and developing sufficient trust and rapport to encourage them to engage in self-care and, ideally, access services. Locating those in need was an important first step and meant trekking to abandoned buildings, under bridges, street benches, parks, encampments, and myriad improvised abodes. Outreach required an understanding of street culture and ways of communicating and learning the delicate balance of engaging without alienating.63 To follow up on health care for clients without a permanent residence, tracking methods64 were designed to identify the different locations that each individual frequented, so outreach workers could locate individuals when needed. For homeless persons with acute health care needs still resistant to accessing services, health care practitioners might accompany outreach workers65; indeed, HCH clinicians in Boston, Massachusetts, developed a training program and manual to offer guidance for this approach.49,66 Those in need of outreach are a broad and heterogeneous group that changes frequently, so flexibility and awareness are key: families, people with mental illness, patients with HIV/AIDS, victims of domestic violence, migrant farmworkers, runaway youths, and veterans are just a few examples of those successfully reached through HCH outreach efforts.

Outreach workers had been used in other settings; however, HCH sites as a group embraced a unique model of outreach to make health care accessible to even the most hidden and underserved persons. The key elements and successful approaches for outreach used by HCH sites have been disseminated in training curricula and, recently, in national outreach guidelines.67

Community collaborations.

The depth and breadth of unmet needs of persons experiencing homelessness significantly increases the importance of developing community collaborations. The “it-takes-a-village” concept is more than a mere platitude but an elemental directive for the HCH model to work. More than primary health care services are needed to ensure individual and family health. Housing, public entitlements, food and clothing, dental and eye care, mental health services, substance use treatment, education, job training, legal services, child care, and parenting help are equally as important. HCH sites established and continued to expand their formal and informal referral networks to enable individuals and families living in homelessness to access services of diverse agencies. Research has shown that only after basic needs—shelter, food, and clothing—are provided are clients willing and able to accept health care services assistance.68,69 Although collaborations are a necessity, they are complicated by resistance from mainstream organizations—because of stigma, lack of sufficient funding or knowledge to address the additional time, and complexity of needs—and from the persons experiencing homelessness themselves.

Case management: 1-stop shopping.

For these reasons, HCH projects have relied heavily on case managers to function as advocates and help link clients to the community and its resources.69,70 They provide a range of services including emotional support, information, advocacy, and guidance through bureaucratic systems to obtain entitlements or other services. The utility of case managers for federally funded programs targeting homeless populations became so apparent that when new programs were launched, such as those providing substance abuse treatment to homeless adults, they required this service.71 A multisite study found that, compared with conventional approaches, case managers were more effective in helping chronically mentally ill persons achieve better social service outcomes.72

By pairing clients who are homeless with a case manager, clients have access to the broader network of agencies connected to the HCH site. This continuum of care systems uses a “no-wrong-door” approach so that clients who want assistance need only go to 1 service provider to gain access to a full network of services. As HCH projects reached out to different subgroups in the homeless population, they expanded their collaborations and referral networks. An example of this strategy was evident among HCH sites serving homeless families and unattached youths, where the network of services expanded to governmental and nonprofit agencies working with foster care children, preschools and Head Start, schools, afterschool programs, adoption centers, and agencies assisting with the sexual exploitation of minors.73 Thus, the HCH sites are independently able to provide a variety of health care services and use their extensive referral networks to ensure a wide range of needs are met.

Medical respite care.

HCH projects have also built innovative community collaborations to address another gap in health care: a need for acute and postacute medical care for homeless persons who are too ill to recover from a physical illness or injury on the streets but not ill enough to warrant hospitalization. Two medical respite facilities first emerged in the mid-1980s to address this gap, but the tightening of hospital budgets through the 1990s, reduced inpatient stays, and bed closures left many communities across the country scrambling to provide services to meet this growing need.74

These facilities vary a great deal, again reflecting the HCH program’s capacity to creatively and flexibly work with existing community resources to address a need; they range from beds set aside within homeless shelters treated by visiting clinicians to stand-alone respite facilities. The 2012 directory of medical respite programs lists 73 current and emerging facilities in 28 states,75 and although still limited, research has documented a range of positive outcomes for their users.76

Consumer advisory boards.

It is perhaps the HCH model’s wholesale embrace of, reliance on, and support for patient-driven care that has played the largest role in its successes. In 1996, when the federal government reauthorized the funding of HCH sites under the status of community health centers, they were required to create a Consumer Advisory Board (CAB). HCH sites integrated this notion into their model and ensured these CABs went far beyond token status by providing CAB members with training on their responsibilities for guiding the HCH leadership on staff hiring and firing, budget issues, hours of service, and procedures.77–79 A National CAB provides support to consumers in developing bylaws and guidelines for their local CABs and has published and disseminated a CAB manual. It also serves as a national collaborative advocacy voice for consumers served in HCHs. A relatively recent innovation is the National CAB’s development of participatory research projects on especially relevant areas of concern or interest to HCH consumers; they engage and support consumers from local CABs to collect data from their peers. One such study was published recently.80

IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The growth and success of the HCH model as the leader in providing health care to the country’s most vulnerable and underserved persons has both positive and negative consequences. Of paramount importance is that the HCH program provides dedicated services to a drastically underserved population and thus, in effect, levels the playing field for accessing quality health care. The innovations highlighted here are examples of specialized care at its best: HCH practitioners have developed and honed the best strategies for reaching out and engaging persons in health care; for consolidating and shaping community-based resources to make them work for those who are hardest to serve; for providing multidisciplinary, holistic health care; and for becoming national paragons for defining, implementing, and embracing patient-driven care.

The HCH model has much to offer mainstream services. One example from primary care is the development of adapted clinical guidelines to assist mainstream health care providers to recognize and successfully treat individuals with the unique needs and barriers associated with their homeless status.81 Their capacity to respond and adapt to needs of individuals and the context of the situation was immensely helpful when hundreds of Hurricane Katrina victims were being bused to a Houston, Texas, football stadium; the Harris County HCH site was among the first to organize and provide emergency health care services.82 Indeed, lessons learned in the HCH model have been and are continuously being developed—always in collaboration with others—into accessible educational and training materials and presentations, policy papers, and newsletters for broad dissemination and application.

The success and growth of the HCH model, though, begs the question: does it let mainstream services off the hook by providing a separate dedicated system of care? It is not necessarily an either–or question of specialized versus mainstream services, but it seems clear that mainstream services could do more and be more responsive and successful in providing quality primary health care for persons experiencing homelessness. There is room for improvement, for example, in reducing stigma, ensuring practitioners have a basic understanding about barriers to care and treatment adherence created by and exacerbated by homelessness, and improving processes for linking patients to community resources.

The advent of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Pub L No. 111–148) presents an especially useful opportunity to reflect on the role of specialized health care for those who are most impoverished.83 The act, signed into law in early 2010, is the most substantial government expansion and restoration of the US health care system since the Medicare and Medicaid legislation was passed in the mid-1960s. The rate of uninsured persons in the United States is anticipated to be cut in half, and the poorest segment of the population, particularly people who are homeless, are expected to benefit. However, it is critical to note that insurance is but 1 of many access barriers that most persons experiencing homelessness face, and as such the HCH model’s capacity to address entrenched and complicated barriers will continue to be a need. Yet as health care becomes more accessible to individuals living in poverty and those on the brink of homelessness, mainstream services would do well to take heed from lessons learned by those who have worked with populations on the margin for decades.

Reflection on the HCH model, and the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also highlight the importance of prevention as the best response to public health issues, along with integrated and multisystem approaches. Intense interest in counting and documenting characteristics of persons experiencing homelessness has ensued throughout the 1990s and 2000s.84,85 On the whole, though, attention has turned more to economic concerns about costs accrued by health and social services than to health needs and how to address them. This limited focus has meant an unhelpful parsing out of which segment of the homeless population costs more, and targeting funding accordingly, rather than addressing the underlying causes and acknowledging homelessness as a public health issue. One example of this is when 3 federal agencies collaborated to fund projects to end chronic homelessness when research showed these individuals were consuming a disproportionate share of shelter resources.86,87 By targeting funds expressly to chronically homeless persons, narrowly defined as “unaccompanied individuals who had a disabling condition and who had been homeless for a year or had three episodes of homelessness in the past four years,”88(p4019) other subpopulations—families, couples, unattached youths—were systematically excluded and not able to benefit. Until we begin to understand homelessness as a consequence of systemic failures and not as a personal failing, our attempts to provide health care to those experiencing it will continue to be piecemeal and reactive, a Band-Aid approach. All people living on the economic margins—and current trends suggest these numbers will continue to swell—deserve access to quality health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the readers of this article for their thoughtful critique and input.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not applicable to this article because it did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Bahr HM. Homelessness, disaffiliation, and retreatism. In: Bahr HM, editor. Disaffiliated Man. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press; 1970. pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassuk EL, Gerson S. Deinstitutionalization and mental health services. Sci Am. 1978;238(2):46–53. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0278-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern MJ. The emergence of the homeless as a public problem. Soc Serv Rev. 1984;58(2):291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brickner PW, O’Donnell F, Scandizzo J. A clinic for male derelicts: a welfare hotel project. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77(4):565–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brickner PW, Kaufman A. Case finding of heart disease in homeless men. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1973;49(6):475–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy M, Leonard P. Dealing with neighbourhood change: a primer on gentrification and policy choices. 2001. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/∼/media/research/files/reports/2001/4/metropolitanpolicy/gentrification.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2013.

- 7.Burt MR, Cohen BE. Differences among homeless single women, women with children and single men. Soc Probl. 1989;36(5):508–524. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klitzner M, Gruenewald PJ, Bamberger E. The assessment of parent-led prevention programs: a preliminary assessment of impact. J Drug Educ. 1990;20(1):77–94. doi: 10.2190/BMB6-7CEE-XUHT-KMEE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi PH, Wright JD, Fisher GA, Willis G. The urban homeless: estimating composition and size. Science. 1987;235(4794):1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.2950592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JD, Devine JA. Counting the homeless: the Census Bureau’s “S-Night” in five US cities. Eval Rev. 1992;16(4):355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arce AA, Tadlock M, Vergare MJ, Shapiro SH. A psychiatric profile of street people admitted to an emergency shelter. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1983;34(9):812–817. doi: 10.1176/ps.34.9.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassuk EL, Rubin L, Lauriat A. Is homelessness a mental health problem? Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(12):1546–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.12.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benda BB, Dattalo P. Homelessness: consequence of a crisis or long-term process? Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(8):884–886. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.8.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer PJ, Shapiro S, Breakey WR, Anthony JC, Kramer M. Mental health and social characteristics of the homeless: a survey of mission users. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(5):519–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.5.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelberg L, Linn LS, Leake BD. Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):191–196. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroll J, Carey K, Hagedorn D, Fire Dog P, Benavides E. A survey of homeless adults in urban emergency shelters. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1986;37(3):283–286. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer PJ. Estimating the prevalence of alcohol, drug, and mental health problems in the contemporary homeless population: a review of the literature. Contemp Drug Probl. 1989;16(3):333–389. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mowbray CT, Bybee D, Cohen E. Describing the homeless mentally ill: cluster analysis results. Am J Community Psychol. 1993;21(1):67–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00938208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Struening E, Padgett DK, Pittman J, Cordova P, Jones M. A typology based on measures of substance abuse and mental disorder. J Addict Dis. 1991;11(1):99–117. doi: 10.1300/j069v11n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelberg L, Linn LS. Demographic differences in health status of homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):601–608. doi: 10.1007/BF02599198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchey FJ, La Gory M, Mullis J. Gender differences in health risks and physical symptoms among the homeless. J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32(1):33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JD. Poor people, poor health: the health status of the homeless. J Soc Issues. 1990;46(4):49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagen JL. Designing services for homeless women. J Health Soc Policy. 1990;1(3):1–16. doi: 10.1300/j045v01n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alperstein G, Arnstein E. Homeless children—a challenge for pediatricians. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1988;35(6):1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassuk EL, Rubin L. Homeless children: a neglected population. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burt MR, Cohen B. America’s Homeless: Numbers, Characteristics, and the Programs that Serve Them. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller DS, Lin EHB. Children in sheltered homeless families: reported health status and use of health service. Pediatrics. 1988;81(5):668–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roman NP, Wolfe PB. Web of Failure: The Relationship between Foster Care and Homelessness. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Susser ES, Lin SP, Conover SA, Struening EL. Childhood antecedents of homelessness in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(8):1026–1030. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.8.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piliavin I, Sosin M, Westerfelt AH, Matsueda RL. The duration of homeless careers: an exploratory study. Soc Serv Rev. 1993;67(4):577–598. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koegel P, Melamid E, Burnam MA. Childhood risk factors for homelessness among homeless adults. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(12):1642–1649. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.12.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zlotnick C, Kronstadt D, Klee L. Foster care children and family homelessness. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(9):1368–1370. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotnick C, Tam T, Bradley K. Adulthood trauma, separation from one’s children and homeless mothers. Community Ment Health J. 2007;43(1):13–32. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inciardi JA. ’s introduction: the crack epidemic revisited. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24(4):305–306. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US General Accounting Office. Drug Abuse: The Crack Cocaine Epidemic—Health Consequences and Treatment. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenheck R, Leda C, Gallup P et al. Initial assessment data from a 43-site program for homeless chronic mentally ill veterans. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(9):937–942. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.9.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenzel SL, Bakhtiar L, Caskey N et al. Predictors of homeless veterans’ irregular discharge status from a domiciliary care program. J Ment Health Adm. 1995;22(3):245–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02521120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brickner PW, Scanlan BC, Conanan B et al. Homeless persons and health care. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(3):405–409. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brickner P, Scharer LK, Conanan BA, Savarese M, Scanlan BC. Under the Safety Net: The Health and Social Welfare of the Homeless in the United States. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelberg L, Linn LS. Social and physical health of homeless adults previously treated for mental health problems. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(5):510–516. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ropers RH, Boyer R. Perceived health status among the new urban homeless. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(8):669–678. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAdam JM, Brickner PW, Scharer LL, Crocco JA, Duff AE. The spectrum of tuberculosis in a New York City men’s shelter clinic ( ). Chest. 1990. 1982-1988;97(4):798–805. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torres RA, Mani S, Altholtz J, Brickner PW. Human immunodeficiency virus infection among homeless men in a New York city shelter: association with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(10):2030–2036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlotnick C, Zerger S. Survey findings on characteristics and health status of clients treated by federally funded (US) Health Care for the Homeless programs. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(1):18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schanzer B, Dominquez B, Shrout PE, Caton CLM. Homelessness, health status, and health care use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):464–469. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):170–177. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and house people living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2238–2245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bethesda, MD: Bureau of Primary Health Care; 2011. US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration/Bureau of Primary Health Care. Uniform Data System (UDS) [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connell JJ, Swain SE, Daniels CL, Allen JS. The Health Care of Homeless Persons: A Manual of Communicable Diseases & Common Problems in Shelters and on the Streets. Boston, MA: Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis K, Rowland D. Uninsured and underserved: inequities in health care in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1983;61(2):149–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robertson MJ, Cousineau MR. Health status and access to health services among the urban homeless. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(5):561–563. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fetter RB, Freeman JL. Diagnosis related groups: product line management within hospitals. Acad Manage Rev. 1986;11(1):41–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.US General Accounting Office. Payment for inpatient alcoholism detoxification and rehabilitation services under Medicare needs attention. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office and Health Care Financing Administration; 1985. GAO/HRD-85-60. [Google Scholar]

- 54. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. About. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/about. Accessed December 20, 2012.

- 55.Wright JD, Knight JW, Weber-Burdin E, Lam J. Ailments and alcohol: health status among the drinking homeless. Alcohol Health Res World. 1987;2(3):22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Health Professions Training Assistance Act (99-129) , 42 USC 201 et seq. 1985.

- 57.Institute of Medicine. Homelessness, Health, and Human Needs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 58. McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, 42 USC 11301 et seq. 1987.

- 59. Health Centers Consolidation Act of 1996, 42 USC 254b et seq. 1996.

- 60.US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration/Bureau of Primary Health Care. Bureau of Primary Health Care—Section 330 Grantees Uniform Data System (UDS), Calendar Year 2007 Data. Bethesda, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration/Bureau of Primary Health Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). 2012. National Summary for Heathcare for Homeless, Table 3a. Patients by age and gender. Available at: http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds. Accessed December 2, 2012.

- 62. Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Amendments Act of 1990, Public Law No. 101-645, 42 USC 11301, Title VI § 340(s)

- 63.Blankertz LE, Cnaan RA, White K, Fox J, Messinger K. Outreach efforts with dually diagnosed homeless persons. Fam Soc. 1990;71(7):387–397. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nichols J, Wright LA, Murphy JF. A proposal for tracking health care for the homeless. J Community Health. 1986;11(3):204–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01338801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levy BD, O’Connell JJ. Health care for homeless persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2329–2332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Connell JJ, Oppenheimer SC, Judge CM et al. The Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program: a public health framework. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1400–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMurray-Avila M. Organizing Health Services for Homeless People: A Practical Guide. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P, Gelberg L. Determinants of regular source of care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Med Care. 1997;35(8):814–830. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perlman BB, Melnick G, Kentera A. Assessing the effectiveness of a case management program. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36(4):405–407. doi: 10.1176/ps.36.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weil M, Karls JM. Case Management in Human Services Practice: A Systematic Approach to Mobilizing Resources for Clients. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perl HI, Jacobs ML. Case management models for homeless persons with alcohol and other drug problems: an overview of the NIAAA research demonstration program. In: Ashery RS, editor. Progress and Issues in Case Management. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1992. pp. 208–222. NIDA Research Monograph 127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lam JA, Rosenheck R. Street outreach for homeless persons with serious mental illness: is it effective? Med Care. 1999;37(9):894–907. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zlotnick C, Marks L. Case management services at ten federally funded sites targeting homeless children and their families. Child Serv (Mahwah NJ) 2002;5(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zerger S, Doblin B, Thompson L. Medical respite care for homeless people: a growing national phenomenon. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(1):36–41. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Medical Respite: What is Medical Respite Care? 2012. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/resources/clinical/medical-respite. Accessed December 20, 2012.

- 76.Doran KM, Ragins KT, Gross CP, Zerger S. Medical respite programs for homeless patients: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2):499–524. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.National Health Care for the Homeless Council. National Consumer Advisory Board: Summary of Health Care for the Homeless Consumer Governance Requirements. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zlotnick C, Wright M, Sanchez RM, Murga-Kusnir R, Te’o-Bennett I. Adaptation of community based participatory research methods to gain community input on identifying indicators of successful parenting. Child Welfare. 2010;89(4):9–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Meinbresse M, Jenkins D, Grassette A, et al. Exploring the experiences of violence among individuals who are homeless using a consumer-led approach. Violence Vict. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Strehlow AJ, Kline S, Zerger S, Zlotnick C, Profitt B. Health care for the homeless assesses the use of adapted clinical practice guidelines. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(11):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2005.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Scott M. Hurricane Katrina and Harris County Health System Healthcare for the Homeless. Keynote Address presented at: 19th Annual National Meeting of the Health Care for the Homeless Council; June 2006; Portland, OR.

- 83. Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act, P.L. 111-148, 42 U.S.C. 18001 § 2001, 124 Statute 271, Title II Stat. 271; 2010.

- 84.US Department of Housing & Urban Development. The Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR) Washington, DC: Office of Community Planning and Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 85.US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) Washington, DC: Office of Community Planning and Development; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hearing on H.R. 217 Homeless Housing Programs Consolidation and Flexibility Act before the Committee on Banking and Financial Services, Subcommittee on Housing and Community Opportunity, 105th Cong. 1997. Testimony of Dennis P. Culhane, PhD, University of Pennsylvania.

- 87.Culhane DP, Kuhn R. Patterns and determinants of public shelter utilization among homeless adults in New York City and Philadelphia. J Policy Anal Manage. 1998;17(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 88. US Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). (2003). Notice of funding availability for the Collaborative Initiative to help end chronic homelessness. Federal Register, 68(17/Notices [January 27, 2003]), 4017-4046.